Flemish dialects

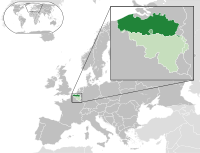

Flemish or Belgian Dutch (Belgisch-Nederlands [ˈbɛl̪ɣ̟is̪ ˈn̪eːd̪ərl̪ɑn̪t̪s̪] , or Vlaams) is the Dutch language as spoken in Flanders, the northern part of Belgium,[1][2][3] be it standard (as used in schools, government and the media)[4] or informal (as used in daily speech, "nl" [ˈtʏsə(n)ˌtaːɫ]).[5] There are four principal Dutch dialects in Flanders: Brabantian, East Flemish, West Flemish, and Limburgish. The latter two are sometimes considered separate languages.[6]

Linguistically, 'Flemish' is sometimes used as a term for the language of the former County of Flanders,[7] especially West Flemish.[8] However, as a result of political emancipation of the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium, the combined culture of that region (which consists of West Flanders, East Flanders, Flemish Brabant, Antwerp, Limburg and Brussels) has come to be known as 'Flemish' and so sometimes are the four dialects or the common intermediate language.[9] Despite the name, Brabantian and in particular its Antwerp dialect is the dominant contributor to the Flemish tussentaal. Using it for the official language in Flanders is misleading: the only official language in Flanders is standard Dutch.[10]

Dutch in Flanders

Dutch is the majority language in Belgium, being spoken natively by three-fifths of the population. It is accorded equal legal status as a national language, with French and German, and is the only official language of the Flemish Region.

The various Dutch dialects spoken in Belgium contain a number of lexical and a few grammatical features which distinguish them from the standard Dutch.[11] As in the Netherlands, the pronunciation of Standard Dutch is affected by the native dialect of the speaker.

All Dutch dialect groups spoken in Belgium are spoken in adjacent areas of the Netherlands as well. At the same time East Flemish forms a continuum with both Brabantic and West Flemish. Standard Dutch is primarily based on the Hollandic dialect[citation needed] (spoken in the Western provinces of the Netherlands) and on Brabantian, which is the most dominant Dutch dialect of the Southern Netherlands and Flanders.

Phonological differences

Among Flemish vowels is the diphthong "ou" / "au". (ou) as in bout (bolt) and (au) as in fauna is realized as [ɔ̞u] (and more often as [ɔ̞ː] due to a strong tendency towards monophthongization), whereas in northern Dutch it is realized as [ʌu]. Among consonants, the northern Dutch pronunciation of "w" (as in wang cheek) is [ʋ], in some southern Dutch dialects it is [β̞] or [w]. Probably the most obvious difference between northern and southern Dutch is in the sounds spelled ⟨ch⟩ and ⟨g⟩. The sound spelled ⟨ch⟩ is a voiceless velar fricative [x] in Northern Dutch and a voiceless prevelar fricative [x̟] in Southern Dutch.[12] In the North the sound spelled ⟨g⟩ is usually realized as voiceless velar fricative [x] or voiceless uvular fricative [χ], whereas in the South the distinction between voiced and unvoiced has been preserved and ⟨g⟩ is pronounced as voiced pre-velar fricative /ɣ̟/.

Consonants

- ⟨w⟩ realised as [β̞]

- ⟨ch⟩ and ⟨g⟩ pronounced as (voiceless resp. voiced) front-velars, not as palatals, as often claimed.

- alveolar consonants (⟨n⟩, ⟨l⟩, ⟨s⟩, ⟨z⟩,⟨t⟩ and ⟨d⟩) are pronounced as denti-alveolars

Vowels

The difference between short and long vowels tends to be quantitive instead of qualitative, especially in the influential Brabantic pronunciation.

Diphthongs

Strong tendency towards monophthongisation.

- ⟨au⟩/⟨ou⟩ realised as [ɔ̞ː]

- ⟨ij⟩/⟨ei⟩ realised as [ɛ̞ː]

- ⟨ui⟩ realised as [œː]

Lexical differences

Flemish includes more French loanwords in its everyday vocabulary than does Netherlands Dutch,[13] but there are exceptions: for example, the former Belgian gendarmerie was known as the Rijkswacht ("Guard of the Realm") in Belgium while the equivalent body in the Netherlands is the Koninklijke Marechaussee ("Royal Military Constabulary").

The traditionally most spoken Dutch dialect in Belgium, Brabantian, has had a large influence on the vocabulary used in Belgium.[5] Examples include beenhouwer (Brabantian) and slager (Hollandic), both meaning butcher (slager is however used in Belgium to mean the kind of butcher who sells salami, sausages, etc.: cf. the difference between beenhouwerij (butcher's shop) and slagerij (delicatessen)); also schoon (Brabantian) vs. mooi (Hollandic) "beautiful" (however Dutch courses for Belgian French-speakers usually teach schoon=beautiful, mooi=pretty). Another notable difference is ge / gij ("you" in Brabantian and "thou / thee" in the Dutch Bible, originally translated by Belgian Protestants fleeing the Inquisition under Philip II of Spain) vs. je / jij ("you" singular in Hollandic), jullie ("you" plural in Hollandic). The changes (isoglosses) from northern to southern Dutch dialects are somewhat gradual, both vocabulary-wise and phonetically, and the boundaries within coincide with territorial borders. There is a distinct boundary located in the river area of the Netherlands, a historical border of the Roman empire, south of which "Brabants" is spoken, a Dutch dialect with some of the phonological traits commonly associated with Belgium. A second distinct border area is located around the border with the Belgian territories, where the transition is mostly lexical, but also with an intensification of the phonological diversion from northern Dutch. An exception to the border with the Belgian territories for this border is Zeelandic Flanders ("Zeeuws-Vlaanderen"), a part of the Netherlands where Flemish is spoken.

The differences between Dutch in the Netherlands and Flemish are significant enough for Flemish and Dutch television shows with rather informal speech customarily to become subtitled for the other country in the standard language.[14]

In 2009, one of the main publishers of Dutch dictionaries, Prisma, published the first Dutch dictionary that distinguished between the two natiolectic varieties "Nederlands Nederlands" (or "Netherlandish Dutch") and "Belgisch Nederlands" ("Belgian Dutch"), treating both variations as equally correct. The selection of the "Flemish Dutch" words was based on the Referentiebestand Belgisch Nederlands (RBBN): an electronic database built under the supervision of Prof. Dr. W. Martin (Free University in Amsterdam, Netherlands) and Prof. Dr. W. Smedts (Catholic University in Leuven, Belgium).

Professor Willy Martin, one of the Flemish editors, claimed that the latter expressions are "just as correct" as the former. This formed a break with the previous lexicologists' custom of indicating Dutch words that are mostly only used in Flanders, while not doing the same for Dutch words mostly only used in the Netherlands, which could give the impression that only usage in the Netherlands defines the standard language.

In the Dutch language, around 3,500 words exist which are considered "Flemish Dutch", and 4,500 words which are considered "Netherlands Dutch".[15][16]

In November 2012 the Belgian radio channel Radio 1 wrote a text with many Flemish words and asked several Dutch speaking people to "translate" it into general Dutch. Almost no inhabitant of The Netherlands was able to make a correct translation, whereas almost all Flemings succeeded.[17][18]

Tussentaal

The supra-regional, semi-standardized colloquial form (mesolect) of Dutch spoken in Belgium, which uses the vocabulary and the sound inventory of the Brabantic dialects, is often called nl ("in-between-language" or "intermediate language", i.e. between dialects and standard Dutch).[19] Its evolution is somewhat similar to the emergence of Poldernederlands in the Netherlands, a medium of everyday speech heavily influenced by Hollandic.[citation needed] Poldernederlands and Tussentaal are sociolects (not dialects or separate standard forms).[citation needed]

The tussentaal is a primarily informal variety of speech which occupies an intermediate position between regional dialects and the standard language. It incorporates phonetic, lexical and grammatical elements that are not part of the standard language but are drawn from local dialects. It is a relatively new phenomenon that has been gaining popularity during the past decades. Some linguists note that it seems to be undergoing a process of (limited) standardisation.[20][21]

Etymology

The adjective Flemish (first attested as flemmysshe, c. 1325;[22] cf. Flæming, c. 1150),[23] meaning "from Flanders", was probably borrowed from Old Frisian.[24] The name Vlaanderen was probably formed from a stem flām-, meaning "flooded area", with a suffix -ðr- attached.[25] The Old Dutch form is flāmisk, which becomes vlamesc, vlaemsch in Middle Dutch and Vlaams in Modern Dutch.[26]

See also

- Belgian French

- French Flemish, the West Flemish dialect as spoken in France

- Zeelandic, a transitional dialect between West Flemish and Hollandic

References

- ^ Leidraad van de Taaltelefoon. Dienst Taaladvies van de Vlaamse Overheid (Department for Language advice of the Flemish government).

- ^ Harbert, The Germanic Languages, CUP, 2007

- ^ Jan Kooij, "Dutch", in Comrie, ed., The World's Major Languages, 2nd ed. 2009

- ^ Speech Rate in a Pluricentric Language: A Comparison Between Dutch in Belgium and the Netherlands (abstract). Language and Speech, Vol. 47, No. 3, 297-308 (2004). By Jo Verhoeven, Guy De Pauw, and Hanne Kloots of the University of Antwerp.

- ^ a b Tussen spreek- en standaardtaal. Koen Plevoets. Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.

- ^ Their ISO 639-3 codes are, vls and lim, respectively

- ^ König & Auwera, eds, The Germanic Languages, Routledge, 1994

- ^ Ethnologue (1999-02-19). "Linguistic map of Benelux". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 2013-10-17.

- ^ "Vlaams". Ethnologue. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ "Language and territoriality in Flanders in a historical and international context publisher=Flanders.be". Retrieved 2014-01-25.

{{cite web}}: Missing pipe in:|title=(help) - ^ G. Janssens and A. Marynissen, Het Nederlands vroeger en nu (Leuven/Voorburg 2005), 155 ff.

- ^ Pieter van Reenen; Nanette Huijs (2000). "De harde en de zachte g, de spelling gh versus g voor voorklinker in het veertiende-eeuwse Middelnederlands" (PDF). Taal en Tongval, 52(Thema nr.), 159-181 (in Dutch). Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- ^ G. Janssens and A. Marynissen, Het Nederlands vroeger en nu (Leuven/Voorburg 2005), 156

- ^ "Vlaamse TV kijkers verstaan geen Hollands (Flemish TV viewers do not understand Hollandic)". Taalunieversum.org. 2010-01-26. Retrieved 2012-01-19.

- ^ Auteur: Dirk Musschoot (2009-12-06). "Nederlands uit Nederland of uit Vlaanderen: het kan allebei - Primeur: Prisma-woordenboek duidt regionaal gebruik aan". Nieuwsblad.be. Retrieved 2012-01-19.

- ^ "Belgisch-Nederlands in de vertaalpockets". Prismawoordenboeken.nl. Retrieved 2012-01-19.

- ^ redactie. "Nieuwsblad: De voor Nederlanders meest onbegrijpelijke Vlaamse tekst". Demorgen.be. Retrieved 2013-10-17.

- ^ donderdag 08 november 2012 (2012-11-08). "Radio 1: De voor Nederlanders meest onbegrijpelijke Vlaamse Tekst". Radio1.be. Retrieved 2013-10-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Geeraerts, Dirk. 2001. "Een zondagspak? Het Nederlands in Vlaanderen: gedrag, beleid, attitudes". Ons Erfdeel 44: 337-344" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-01-19.

- ^ G. Janssens and A. Marynissen, Het Nederlands vroeger en nu (Leuven/Voorburg 2005), 196.

- ^ "Algemeen Vlaams". VlaamseTaal.be. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- ^ "entry Flēmish". Middle English Dictionary (MED).

- ^ "MED, entry "Flēming"". Quod.lib.umich.edu. Retrieved 2013-10-17.

- ^ "entry Flemish". Online Etymological Dictionary. Etymonline.com. which cites Flemische as an Old Frisian form; but cf. "entry FLĀMISK, which gives flēmisk". Oudnederlands Woordenboek (ONW). Gtb.inl.nl.

- ^ "Entry VLAENDREN; ONW, entry FLĀMINK; Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal (WNT), entry VLAMING". Vroeg Middelnederlandsch Woordenboek (VMNW). Gtb.inl.nl.

- ^ ONW, entry FLĀMISK.