Freedmen's Bureau

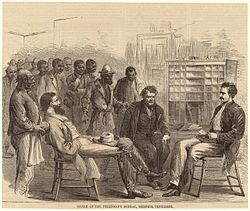

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, usually referred to as simply the Freedmen's Bureau,[1] was a U.S. federal government agency that aided distressed freedmen (freed slaves) during the Reconstruction era of the United States. The Freedmen's Bureau Bill, which established the Freedmen's Bureau in March 3, 1865, was initiated by President Abraham Lincoln and was intended to last for one year after the end of the Civil War.[2] The Freedmen's Bureau was an important agency of the early Reconstruction, assisting freedmen (freed ex-slaves) in the South. The Bureau was part of the United States Department of War. Headed by Union Army General Oliver O. Howard, the Bureau started operations in 1865. Throughout the first year, it became clear that these tasks were more difficult than had been previously believed as conservative Southerners established Black Codes detrimental to African-American civil rights.

Not withstanding, the Bureaus powers were expanded to help find lost families for African Americans and teach them to read and write so they could better do so themselves.[3][4] Bureau agents also served as legal advocates for African Americans in both local and national courts, mostly in cases dealing with family issues.[3] The Bureau encouraged former plantation owners to rebuild their plantations, urged freed Blacks to gain employment, kept an eye on contracts between labor and management, and pushed both whites and blacks to work together as employers and employees rather than as masters and as slaves.[3]

In 1866, Congress renewed the charter for the Bureau, which President Andrew Johnson vetoed because it encroached into states' rights, used the military in peacetime, and would keep freed slaves from becoming independent.[2][5] By 1869, the Bureau had lost most of its funding and as a result been forced to cut much of its staff.[2] By 1870 the Bureau had been considerably weakened due to the rise of Ku Klux Klan violence in the South.[2] In 1872, Congress abruptly abandoned and shut down the Bureau, without informing Howard, who had been controversially transferred to Arizona by President Ulysess S. Grant to settle hostilities between the Apache Indians and settlers. Grant's Secretary of War William W. Belknap, was hostile to Howard's leadership and authority at the Bureau. Howard had approved of the closure, believing the Bureau to be temporary, but he was upset that he had not been at his office in Washington D.C. when the Bureau closed.

Achievements

Day-to-day duties

The Bureau helped solve everyday problems of the newly freed slaves, such as clothing, food, water, health care, communication with family members, and jobs. It distributed 15 million rations of food to African Americans[6] and set up a system where planters could borrow rations in order to feed freedmen they employed. Although the Bureau set aside $350,000 for this service, only $35,000 (10%) was borrowed.[citation needed]

Despite the good intentions, efforts, and limited success of the Bureau, medical treatment of the freedmen was severely deficient.[7]

Gender roles

Freedman's Bureau agents, at first, complained that freed women were refusing to contract their labor. They attempted to make freed women work by insisting that their husbands sign contracts making the whole family to work in the cotton industry, and by declaring that unemployed freed women should be treated as vagrants just as men were. The Bureau did allow some exceptions such as married women with employed husbands and some "worthy" women who had been widowed or abandoned and had large families of small children and thus could not work. "Unworthy" women, meaning the unruly and prostitutes, were the ones usually subjected to punishment for vagrancy.[8]

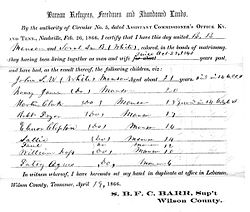

Under slavery, some marriages were informal, though there are many documented accounts of slave owners presiding over marriage ceremonies for their slaves. Others were separated during wartime chaos. The Bureau agents helped many families in their attempts to reunite after the war. The Bureau had an informal regional communications system that allowed agents to send inquiries and provide answers. It sometimes provided transportation to reunite families. Freedmen and freed women turned to the Bureau for assistance in resolving issues of abandonment and divorce.

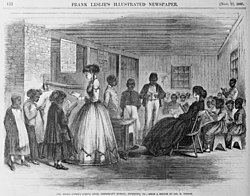

Education

The most widely recognized among the achievements of the Freedman’s Bureau are its accomplishments in the field of education. Prior to the Civil War, no southern state had a system of universal, state-supported public education. Former slaves wanted such a system while the wealthier whites opposed the idea. Freedmen had a strong desire to learn to read and write and worked hard to establish schools in their communities prior to the advent of the Freedmen's Bureau.

Oliver Otis Howard was the first Freedmen's Bureau Commissioner. Through his leadership the bureau was divided into four divisions: Government-Controlled Lands, Records, Financial Affairs, and Medical Affairs. Education was considered part of the Records division. Howard turned over confiscated property, government buildings, books, and furniture to superintendents to be used in the education of freedmen and provided transportation and room and board for teachers.

By 1866, missionary and aid societies worked in conjunction with the Freedmen's Bureau to provide education for former slaves. The American Missionary Association was particularly active, establishing eleven colleges in southern states for the education of freedmen. The primary focus of these groups was to raise funds to pay teachers and manage schools, while the secondary focus was the day-to-day operation of individual schools. After 1866, Congress appropriated some funds to use in the freedmen's schools. The main source of educational revenue for these schools came through a Congressional Act that gave the Freedmen's Bureau the power to seize Confederate property for educational use.

George Ruby, an African American, served as teacher and school administrator and as a traveling inspector for the Bureau, observing local conditions, aiding in the establishment of black schools, and evaluating the performance of Bureau field officers. Blacks supported him, but planters and other whites opposed him.[9]

Overall, the Bureau spent $5 million to set up schools for blacks. By the end of 1865, more than 90,000 former slaves were enrolled as students in public schools. Attendance rates at the new schools for freedmen were between 79 and 82 percent. Brigadier General Samuel Chapman Armstrong created and led Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in 1868.

The Freedmen's Bureau published their own freedmen's textbook. They emphasized the bootstrap philosophy, meaning that everyone had the ability to work hard and pull themselves up by their bootstraps and do better in life.[clarification needed] These readers had some traditional literacy lessons and others on the life and works of Abraham Lincoln, excerpts from the Bible focused on forgiveness, biographies of famous African Americans with emphasis on their piety, humbleness and industry; and essays on humility, the work ethic, temperance, loving your enemies, and avoiding bitterness.[10]

By 1870, there were more than 1,000 schools for freedmen in the South.[11] J. W. Alvord, an inspector for the Bureau, wrote that the freedmen "have the natural thirst for knowledge," aspire to "power and influence … coupled with learning," and are excited by "the special study of books." Among the former slaves, children and adults sought this new opportunity to learn. After the Bureau was abolished, some of its achievements collapsed under the weight of white violence against schools and teachers for blacks. After the 1870s, when white Democrats regained power of southern governments, they reduced funds available to fund public education. In the 1890s they passed Jim Crow laws establishing legal segregation of public places. Segregated schools and other services for blacks were consistently underfunded.[6]

By 1871, Northerners' interest in reconstructing the South with military power had waned. Northerners were beginning to tire of the effort that Reconstruction required, were discouraged at the high rate of continuing violence around elections, and were ready for the South to take care of itself. All of the southern states had created new constitutions that established universal, publicly funded education. Groups based in the North began to redirect their money toward universities and colleges founded to educate African-American leaders.

Teachers

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

Until recently historians had believed that most Bureau teachers were well-educated women motivated by religion and abolitionism. New research finds that half the teachers were southern whites; one-third were blacks, and one-sixth were northern whites.[12] Few were abolitionists; few came from New England. Men outnumbered women. The salary was the strongest motivation except for the northerners, who were typically funded by northern organizations and had a humanitarian motivation. As a group, only the black cohort showed a commitment to racial equality; they were the ones most likely to remain teachers. The school curriculum resembled that of schools in the north.[13]

Colleges

The building and opening of schools of higher learning for African Americans coincided with the shift in focus for the Freedmen's Aid Societies from an elementary education for all African Americans to a high school and college education for African-American leaders. Both of these events worked in concert with concern on the part of white officials working with African Americans in the South. These officials were concerned about the lack of a moral or financial foundation seen in the African-American community and traced that lack of foundation back to slavery.

Generally, they believed that blacks needed help to enter a free labor market and reconstruct family life. Heads of local American Missionary Associations sponsored various educational and religious efforts for African Americans. Samuel Chapman Armstrong of the Hampton Institute and Booker T. Washington began the call for institutions of higher learning so black students could leave home and "live in an atmosphere conducive not only to scholarship but to culture and refinement".[14]

Most of these colleges, universities and normal schools combined what they believed were the best fundamentals of a college with that of the home. At the majority of these schools, students were expected to bathe a prescribed number of times per week, maintain an orderly living space, and present a particular appearance. At many of these institutions, Christian principles and practices were also part of the daily regime.

Educational legacy

Despite the untimely dissolution of the Freedman's Bureau, its legacy still lives on through historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). Under the direction and sponsorship of the Bureau, together with the American Missionary Association in many cases, from approximately 1866 until its termination in 1872, an estimated 25 institutions of higher learning for black youth were established,[15] many of which remain in operation today (for example, St. Augustine's College, Fisk University, Johnson C. Smith University, Clark Atlanta University, Dillard University, Shaw University, Virginia Union University, and Tougaloo College).

As of 2009[update], there exist approximately 105 United Negro College Fund HBCUs that range in scope, size, organization and orientation. Under the Education Act of 1965, Congress officially defined an HBCU as "an institution whose principal missions were and are the education of Black Americans". HBCUs graduate over 50% of African-American professionals, 50% of African-American public school teachers, and 70% of African-American dentists. In addition, 50% of African Americans who graduate from HBCUs go on to pursue graduate or professional degrees. One in three degrees held by African Americans in the natural sciences, and half the degrees held by African Americans in mathematics were earned at HBCUs.[16]

Perhaps the best known of these institutions is Howard University, founded in Washington, D.C., in 1867, with the aid of the Freedmen’s Bureau. It was named for the commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, General Oliver Otis Howard.[17]

Church establishment

After the Civil War, control over existing churches was a contentious issue. The Methodist denomination had split into regional associations prior to the war. In some cities, Northern Methodists seized control of Southern Methodist buildings. Numerous northern denominations, including the independent black denominations of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) and African Methodist Episcopal Zion, sent missionaries to the South to help the freedmen. By this time the independent black denominations were increasingly well organized and prepared to evangelize to the freedmen. Within a decade, the AME and AME Zion churches had gained hundreds of thousands of new members and were rapidly organizing new congregations.[18]

Even before the war, blacks had established independent Baptist congregations in some cities and towns, such as Silver Bluff, Charleston, Petersburg, and Richmond. In many places, especially in more rural areas, they shared public services with whites. Often enslaved blacks met secretly to conduct their own services away from white supervision or oversight.[18] After the war, freedmen mostly withdrew from multi-racial congregations in order to be free to worship as they pleased away from white supervision.

Northern mission societies raised funds for land, buildings, teachers' salaries, and basic necessities such as books and furniture. For years they used networks throughout their churches to raise money for freedmen's education and worship.[19]

Continuing insurgency

Most of the assistant commissioners, realizing that African Americans would not receive fair trials in the civil courts, tried to handle black cases in their own Bureau courts. Southern whites objected that this was unconstitutional. In Alabama, state and county judges were commissioned as Bureau agents. They were to try cases involving blacks with no distinctions on racial grounds. If a judge refused, martial law could be instituted in his district. All but three judges accepted their unwanted commissions, and the governor urged compliance.[20]

Perhaps the most difficult region was Louisiana's Caddo-Bossier district. It had not experienced wartime devastation or Union occupation. Understaffed and weakly supported by federal troops, well-meaning Bureau agents found their investigations blocked and authority undermined at every turn by recalcitrant plantation owners. Murders of freedmen were common, and suspects in these cases went unprosecuted. Bureau agents did manage to negotiate labor contracts, build schools and hospitals, and provide the freedmen a sense of their own humanity through the agents' willingness to help.[21]

In March 1872, at the request of President Ulysses S. Grant and the Secretary of the Interior, Columbus Delano, General Howard was asked to temporarily leave his duties as Commissioner of the Bureau to deal with Indian affairs in the west. Upon returning from his assignment in November 1872, General Howard discovered that the Bureau and all of its activities had been officially terminated by Congress, effective as of June (Howard, 1907). In his autobiography, General Howard expressed great frustration in regard to what had taken place without his knowledge, stating "the legislative action, however, was just what I desired, except that I would have preferred to close out my own Bureau and not have another do it for me in an unfriendly manner in my absence."[22] All documents and matters pertaining to the Freedmen's Bureau were transferred from the office of General Howard to the War Department of the United States Congress.

State reports in May 1866

The following was summary on a state by state basis from the Freedmen's Bureau report from May 8, 1866 and filed by Generals Steedman and Fullerton, the Commissioners appointed by the President to investigate the operations of the Freedmen's Bureau in the Southern States.[23]

Virginia

The Freedmen's bureau had, 58 clerks and superintendents of farms, paid average monthly wages $78.50; 12 assistant superintendents, paid average monthly wages 87.00; and 163 laborers, paid average monthly wages 11.75; as personnel in the state of Virginia. Other personnel included orderlies and guards.

The Bureau fed 9,000 to 10,000 blacks a month over the winter, explaining:

- "A majority of the freedmen to whom this subsistence has been furnished are undoubtedly able to earn a living if they were removed to localities where labor could be procured. The necessity for issuing rations to this class of persons results from their accumulation in large numbers in certain places where the land is unproductive and the demand for labor is limited. As long as these people remain in the present localities, the civil authorities refuse to provide for the able-bodied, and are unable to care for the helpless and destitute among them, owing to their great number and the fact that very few are residents of the counties in which they have congregated during the war. The necessity for the relief extended to these people, both able-bodied and helpless, by the Government, will continue as long as they remain in their present condition, and while rations are issued to the able-bodied they will not voluntarily change their localities to seek places where they can procure labor.'[24]

North Carolina

In North Carolina, the bureau employed: 9 contract surgeons, at $100 per month; 26 hospital attendants, at average pay each per month $11.25; 18 civilian employees, clerks, agents, etc., at an average pay per month of $17.20; 4 laborers, at an average pay per month of $11.90; enlisted men are detailed as orderlies, guards, etc., by commanding officers of the different military posts where officers of the Bureau are serving.[25]

Some misconduct was reported to the bureau main office that bureau agents were using their posts for personal gains. Colonel E. Whittlesey, who interrogated on this matter had stated that he was not involved in nor knew of anyone involved in such activities. Also, the arbitrary powers of the bureau, making arrests, imposing fines, and inflicting punishments, disregarding the local laws and especially the statute of limitations, caused resentment toward the federal government in general. These powers invoked negative feelings in many southerners that sparked many to want the agency to leave.

The recommendation of Steedman and Fullerton echoed the conclusion they had in Virginia which was to withdraw the bureau and turn day-to-day responsibility over to the military.

South Carolina

In South Carolina, the bureau employed, nine clerks, at average pay each per month $108.33, one rental agent, at monthly pay of $75.00, one clerk, at monthly pay of $50.00, one storekeeper, at monthly pay of $85.00, one counselor, at monthly pay of $125.00, one superintendent of education, at monthly pay of $150.00, one printer, at monthly pay of $100.00, one contract surgeon, at monthly pay of $100.00, twenty-five laborers, at average pay per month $19.20.

The bureau management had a systemic problem that was bad at the leadership position. General Saxton was head of the bureau operations in South Carolina and had performed his with numerous mistakes and blunders that made matters bad for those the bureau were trying to help. Saxton was described as being pernicious. He was replaced by Brigadier General R.K. Scott. Steedman and Fullerton described Scott as energetic and a competent officer. It appeared that he took great pains to turn thing around and correct the mistakes made by his predecessors.

There had reports of murder of freedmen from a band of outlaws. These outlaws were thought to be from other states such as Texas, Kentucky and Tennessee who were apart of the rebel army. When citizens were asked why the perpetrators had not been arrested, many answered that the bureau with the support of the military had the primary authority.

In certain areas, such as the sea islands, many freedmen were in a state of destitution. Many had tried to cultivate the land and begin businesses with little to no success.

Georgia

There was no report to make as it had been reported in Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina because the bureau did not operate in the same manner as it had in the before mentioned states. Major General David Tilson was the commissioner for the Georgia bureau office. He had abolished all local and state authorities and established a moched mini United States. In doing so, it created confusion and disorder.

In some area such as the Islands off the coast of Georgia, had been a majority population of freedmen in which great disorganization characterized life on the islands. But order was restored by mid-1865 with the freedmen receiving great economic gains.

Florida

On the whole, the bureau was working effectively for all. Col. T. W. Osborne, the assistant commissioner of the Bureau for Florida had nothing but praise in descriptions from white and blacks alike.

Bureau Records

In 2000, the U.S. Congress passed the "Freedmen's Bureau Preservation Act," which directed the National Archivist to preserve the extensive records of the Bureau on microfilm, and work with educational institutions to index the records.[26] In addition to the those of the Bureau headquarters, assistant commissioners, and superintendents of education, the National Archives now has records of the field offices, marriage records, and records of the Freedmen's Branch of the Adjutant General on microfilm. These constitute a major source of documentation on the operations of the Bureau, political and social conditions in the Reconstruction Era, and the genealogies of freedpeople.[27]

See also

Bibliography

- see also Reconstruction: Bibliography

General

- Bentley George R. A History of the Freedmen's Bureau (1955); old fashioned overview

- Carpenter, John A.; Sword and Olive Branch: Oliver Otis Howard (1999); full biography of Bureau leader

- Cimbala, Paul A. and Trefousse, Hans L. (eds), The Freedmen's Bureau: Reconstructing the American South After the Civil War. 2005; essays by scholars.

- Colby, I. C. (1985). "The Freedmen's Bureau: From Social Welfare to Segregation," Phylon, 46, 219–230.

- W. E. Burghardt Du Bois, The Freedmen's Bureau (1901).

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (1988).

- Goldberg, Chad Alan. Citizens and Paupers: Relief, Rights, and Race, from the Freedmen's Bureau to Workfare (2007) compares the Bureau with the WPA in the 1930s and welfare today excerpt and text search

- Litwack, Leon F. Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery, 1979.

- McFeely, William S. Yankee Stepfather: General O.O. Howard and the Freedmen (1994); biography of Bureau's head. excerpt and text search

Education

- Abbott, Martin. "The Freedmen's Bureau and Negro Schooling in South Carolina," South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 57#2 (Apr., 1956), pp. 65–81 in JSTOR

- Anderson, James D. The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860–1935 (1988).

- Butchart, Ronald E. Northern Schools, Southern Blacks, and Reconstruction: Freedmen's Education, 1862-1875 (1980).

- Crouch, Barry A. "Black Education in Civil War and Reconstruction Louisiana: George T. Ruby, the Army, and the Freedmen's Bureau" Louisiana History 1997 38(3): 287–308. Issn: 0024-6816.

- Goldhaber, Michael. "A Mission Unfulfilled: Freedmen's Education in North Carolina, 1865–1870" Journal of Negro History 1992 77(4): 199–210. in JSTOR

- Hornsby, Alton. "The Freedmen's Bureau Schools in Texas, 1865–1870," Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 76#4 (April, 1973), pp. 397–417 in JSTOR

- Jackson, L. P. "The Educational Efforts of the Freedmen's Bureau and Freedmen's Aid Societies in South Carolina, 1862–1872," The Journal of Negro History (1923), vol 8#1, pp 1–40. in JSTOR

- Jones, Jacqueline. Soldiers of Light and Love: Northern Teachers and Georgia Blacks, 1865–1873 (1980).

- Morris, Robert C. Reading, 'Riting, and Reconstruction: The Education of Freedmen in the South, 1861–1870 (1981).

- Myers, John B. "The Education of the Alabama Freedmen During Presidential Reconstruction, 1865–1867," Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 40#2 (Spring 1971), pp. 163–171 in JSTOR

- Parker, Marjorie H. "Some Educational Activities of the Freedmen's Bureau," Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 23#1 (Winter, 1954), pp. 9–21. in JSTOR

- Richardson, Joe M. Christian Reconstruction: The American Missionary Association and Southern Blacks, 1861–1890 (1986)

- Richardson, Joe M. "The Freedmen's Bureau and Negro Education in Florida," Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 31#4 (Autumn, 1962), pp. 460–467. in JSTOR

- Span, Christopher M. "'I Must Learn Now or Not at All': Social and Cultural Capital in the Educational Initiatives of Formerly Enslaved African Americans in Mississippi, 1862–1869," The Journal of African American History, 2002, pp. 196–222.

- Tyack, David, and Robert Lowe. "The Constitutional Moment: Reconstruction and Black Education in the South," American Journal of Education, Vol. 94#2 (February 1986), pp. 236–256 in JSTOR

- Williams, Heather Andrea; "'Clothing Themselves in Intelligence': The Freedpeople, Schooling, and Northern Teachers, 1861–1871", The Journal of African American History, 2002, pp. 372+.

- Williams, Heather Andrea. Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom (2006). online edition

Specialized studies

- Bethel, Elizabeth . "The Freedmen's Bureau in Alabama," Journal of Southern History Vol. 14, No. 1, (February 1948) pp. 49–92 in JSTOR.

- Bickers, John M. "The Power to Do What Manifestly Must Be Done: Congress, the Freedmen's Bureau, and Constitutional Imagination", Roger Williams University Law Review, Vol. 12, No. 70, 2006 online at SSRN.

- Cimbala, Paul A. "On the Front Line of Freedom: Freedmen's Bureau Officers and Agents in Reconstruction Georgia, 1865–1868". Georgia Historical Quarterly 1992 76(3): 577–611. Issn: 0016-8297.

- Cimbala, Paul A. Under the Guardianship of the Nation: the Freedmen's Bureau and the Reconstruction of Georgia, 1865–1870 (1997).

- Click, Patricia C. Time Full of Trial: The Roanoke Island Freedmen's Colony, 1862–1867 (2001).

- Crouch, Barry. The Freedmen's Bureau and Black Texans (1992).

- Crouch; Barry A. "The 'Chords of Love': Legalizing Black Marital and Family Rights in Postwar Texas" The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 79, 1994.

- Durrill, Wayne K. "Political Legitimacy and Local Courts: 'Politicks at Such a Rage' in a Southern Community during Reconstruction" in Journal of Southern History, Vol. 70 #3, 2004 pp. 577–617.

- Farmer-Kaiser, Mary. "’Are They Not in Some Sorts Vagrants?’ Gender and the Efforts of the Freedmen's Bureau to Combat Vagrancy in the Reconstruction South” Georgia Historical Quarterly 2004 88(1): 25–49. Issn: 0016-8297.

- Farmer-Kaiser, Mary. Freedwomen and the Freedmen's Bureau: Race, Gender, and Public Policy in the Age of Emancipation (Fordham University Press, 2010) 275 pages; describes how freedwomen found both an ally and an enemy for their interests in the Bureau.

- Finley, Randy. From Slavery to Future: the Freedmen's Bureau in Arkansas, 1865–1869 (1996).

- Lieberman, Robert C. "The Freedmen's Bureau and the Politics of Institutional Structure" Social Science History 1994 18(3): 405–437. Issn: 0145-5532.

- Lowe, Richard. "The Freedman's Bureau and Local Black Leadership" Journal of American History 1993 80(3): 989–998. in JSTOR

- Morrow Ralph Ernst. Northern Methodism and reconstruction (1956)

- May J. Thomas. "Continuity and Change in the Labor Program of the Union Army and the Freedmen's Bureau". Civil War History 17 (September 1971): 245–54.

- Oubre, Claude F. Forty Acres and a Mule. (1978).

- Pearson, Reggie L. "'There Are Many Sick, Feeble, and Suffering Freedmen': the Freedmen's Bureau's Health-care Activities During Reconstruction in North Carolina, 1865–1868" North Carolina Historical Review 2002 79(2): 141–181. Issn: 0029-2494 .

- Richter, William L. Overreached on All Sides: The Freedmen's Bureau Administrators in Texas, 1865–1868 (1991).

- Rodrigue, John C. "Labor Militancy and Black Grassroots Political Mobilization in the Louisiana Sugar Region, 1865–1868" in Journal of Southern History, Vol. 67 #1, 2001, pp. 115–45.

- Schwalm, Leslie A. "'Sweet Dreams of Freedom': Freedwomen's Reconstruction of Life and Labor in Lowcountry South Carolina Journal of Women's History, Vol. 9 #1, 1997 pp. 9–32.

- Smith, Solomon K. "The Freedmen's Bureau in Shreveport: the Struggle for Control of the Red River District" Louisiana History 2000 41(4): 435–465. Issn: 0024-6816.

- Williamson, Joel. After Slavery: The Negro in South Carolina during Reconstruction, 1861–1877 (1965).

- Freedmen's Bureau in Texas.

Primary sources

- Berlin, Ira, ed. Free at Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War (1995)

- Howard, O.O. (1907). Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard Major General United States Army (Volume Two). New York: The Baker & Taylor Company.

- Stone, William. "Bitter Freedom: William Stone's Record of Service in the Freedmen's Bureau," edited by Suzanne Stone Johnson and Robert Allison Johnson (2008), memoir by white Bureau official

- Minutes of the Freedmen's Convention, Held in the City of Raleigh, North Carolina, October, 1866

- Freedmen's Bureau Online

- Reports and Speeches

- General Howard's report for 1869: The House of Representatives, Forty-first Congress, second session

References

- ^ A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875. Memory.loc.gov. Retrieved on 2013-07-28.

- ^ a b c d The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow . Jim Crow Stories . Freedmen's Bureau. PBS. Retrieved on 2013-07-28.

- ^ a b c Clayborne Carson, Emma J. Lapsansky-Werner, and Gary B. Nash, The Struggle for Freedom: A History of African Americans, 256.

- ^ Review of Families and Freedom: A Documentary History of African-American Kinship in the Civil War Era, Freedmen & Southern Society Project.

- ^ National Park Service

The Freedmen's Bureau Bill

Freedmen's Bureau Bill First Veto: 1. Johnson was opposed to the use of the military during peacetime. 2. Johnson felt the Bill was a Federal encroachment into state matters. 3. Johnson felt this was "class legislation" for a particular segment of society that: a. Would keep the ex-slaves from being self-sustaining, and b. Had not been done for struggling whites (like he had been as an ex-apprentice). 4. Johnson did not feel that Congress should be making these decisions for unrepresented states. Second veto: Johnson's second objections were the same as his first. - ^ a b Goldhaber 1992

- ^ Pearson 2002 Jim Downs, Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction (NY: Oxford U.P., 2012)

- ^ Farmer-Kaiser, 2004

- ^ Crouch 1997

- ^ West, Earle H. (1982). "Book review of Freedmen's Schools and Textbooks". JSTOR 2294682.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ McPherson, p. 450

- ^ Ronald E. Butchart, Schooling the Freed People: Teaching, Learning, and the Struggle for Black Freedom, 1861-1876 (2010)

- ^ Michelle A. Krowl, "Review of Butchart, Ronald E., Schooling the Freed People: Teaching, Learning, and the Struggle for Black Freedom, 1861-1876", H-SAWH, H-Net Reviews. September, 2011.

- ^ Morris, 1981, p. 160.

- ^ Howard, 1907

- ^ Data from United Negro College Fund.

- ^ Harrison, Robert (2006-02-01). "Welfare and Employment Policies of the Freedmen's Bureau in the District of Columbia". Journal of Southern History (1 Feb 2006). Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- ^ a b "The Church in the Southern Black Community". Documenting the South. University of North Carolina, 2004. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- ^ Morrow 1954

- ^ Foner 1988

- ^ Smith 2000

- ^ Howard, 1907, 447.

- ^ see "Reports of Generals Steedman and Fullerton on the condition of the Freedmen's Bureau in the Southern States"

- ^ from "Reports of Generals Steedman and Fullerton on the condition of the Freedmen's Bureau in the Southern States"

- ^ The United States Army and Navy Journal and Gazette of the Regular and Volunteer Forces. Army and Navy Journal Incorporated. 1865. p. 616. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ^ 114 Stat. 1924

- ^ National Archives

Jim Downs, Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction (NY: Oxford University Press, 2012)