The Fountainhead

| File:TheFountainhead.jpg First edition | |

| Author | Ayn Rand |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Philosophical novel |

| Published | 1943 (Bobbs Merrill) |

| Publication place | United States |

| Pages | 753 (1st edition) |

| OCLC | 300033023 |

The Fountainhead is a 1943 novel by Ayn Rand, and her first major literary success. More than 6.5 million copies of the book have been sold worldwide.

The Fountainhead's protagonist, Howard Roark, is an individualistic young architect who chooses to struggle in obscurity rather than compromise his artistic and personal vision. The book follows his battle to practice what the public sees as modern architecture, which he believes to be superior, despite an establishment centered on tradition-worship. How others in the novel relate to Roark demonstrates Rand's various archetypes of human character, all of which are variants between Roark, the author's ideal man of independence and integrity, and what she described as the "second-handers". The complex relationships between Roark and the various kinds of individuals who assist or hinder his progress, or both, allow the novel to be at once a romantic drama and a philosophical work. Roark is Rand's embodiment of what she believes to be the ideal man, and his struggle reflects Rand's personal belief that individualism trumps collectivism.

The manuscript was rejected by twelve publishers before editor Archibald Ogden at the Bobbs-Merrill Company risked his job to get it published. Despite mixed reviews from the contemporary media, the book gained a following by word of mouth and became a bestseller. The novel was made into a Hollywood film in 1949. Rand wrote the screenplay, and Gary Cooper played Roark.

Plot summary

In the spring of 1922, Howard Roark is expelled from his architecture school for refusing to adhere to the school's conventionalism. Despite an effort by some professors to defend Roark and a subsequent offer to continue, Roark chooses to leave the school. He believes buildings should be sculpted to fit their location, material and purpose elegantly and efficiently, while his critics insist that adherence to historical convention is essential. He goes to New York City to work for Henry Cameron, a disgraced architect whom Roark admires. Peter Keating, a popular but vacuous fellow student, has graduated with high honors. He too moves to New York to take a job at the prestigious architectural firm of Francon & Heyer, where he ingratiates himself with senior partner Guy Francon. Roark and Cameron create inspired work, but rarely receive recognition, whereas Keating's ability to flatter brings him quick success. To hasten his rise to power, Keating bends his skills in manipulation towards the removal of rivals within his firm. His actions culminate in the unintended manslaughter of Lucius Heyer, a senior partner, who dies of a stroke when threatened with blackmail by Keating. Though he occasionally feels guilt for his unethical actions that lead to his partnership within the firm, Keating demonstrates that he will always pursue his lust for prestige regardless of personal cost.

After Cameron retires, Keating hires Roark, who is soon fired for insubordination by Francon. Roark works briefly at another firm and then opens his own office. However, he has trouble finding clients and eventually closes it down. He takes a job at a granite quarry owned by Francon. Meanwhile, Keating has developed an interest in Francon's beautiful, temperamental and idealistic daughter Dominique, who works as a columnist for The New York Banner, a yellow press-style newspaper. While Roark is working in the quarry, he meets Dominique, who has retreated to her family's estate in the same town. There is an immediate attraction between them. Rather than indulge in traditional flirtation, the two engage in a battle of wills that culminates in a rough sexual encounter that Dominique later describes as a rape. Shortly after their encounter, Roark is notified that a client is ready to start a new building, and he returns to New York before Dominique can learn his name.

Ellsworth M. Toohey, author of a popular architecture column in the Banner, is an outspoken socialist who is covertly rising to power by shaping public opinion through his column and his circle of influential associates. Toohey sets out to destroy Roark through a smear campaign he spearheads. Toohey convinces a weak-minded businessman to hire Roark to design a temple dedicated to the human spirit. Given full freedom to design it as he sees fit, Roark includes a nude statue of Dominique, which creates a public outcry. Toohey manipulates the client into suing Roark. At the trial, prominent architects (including Keating) testify that Roark's style is unorthodox and illegitimate. Dominique speaks in Roark's defense, but he loses the case.

Dominique decides that since she cannot have the world she wants, in which men like Roark are recognized for their greatness, she will live completely and entirely in the world she has, which shuns Roark and praises Keating. She offers Keating her hand in marriage. Keating accepts, breaking his previous engagement with Toohey's niece Catherine. Dominique turns her entire spirit over to Keating, doing and saying whatever he wants. She fights Roark and persuades his potential clients to hire Keating instead. Despite this, Roark continues to attract a small but steady stream of clients who see the value in his work.

To win Keating a prestigious commission offered by Gail Wynand, the owner and editor-in-chief of the Banner, Dominique agrees to sleep with Wynand. Wynand then buys Keating's silence and his divorce from Dominique, after which Wynand and Dominique are married. Wynand subsequently discovers that every building he likes was designed by Roark, so he enlists Roark to build a home for himself and Dominique. The home is built, and Roark and Wynand become close friends, although Wynand does not know about Roark's past relationship with Dominique.

Now washed up and out of the public eye, Keating realizes he is a failure. He pleads with Toohey for his influence to get the commission for the much-sought-after Cortlandt housing project. Keating knows his most successful projects were aided by Roark, so he asks for Roark's help in designing Cortlandt. Roark agrees to design it in exchange for complete anonymity and Keating's promise that it will be built exactly as designed. When Roark returns from a long trip with Wynand, he finds that the Cortlandt design has been changed despite his agreement with Keating. Roark dynamites the building to prevent the subversion of his vision.

The entire country condemns Roark, but Wynand finally finds the courage to follow his convictions and orders his newspapers to defend him. The Banner's circulation drops and the workers go on strike, but Wynand keeps printing with Dominique's help. Wynand is eventually faced with the choice of closing the paper or reversing his stance. He gives in; the newspaper publishes a denunciation of Roark over Wynand's signature. At the trial, Roark seems doomed, but he rouses the courtroom with a speech about the value of ego and the need to remain true to oneself. The jury finds him not guilty and Roark wins Dominique. Wynand, who has finally grasped the nature of the "power" he thought he held, shuts down the Banner and asks Roark to design one last building for him, a skyscraper that will testify to the supremacy of man. Eighteen months later, the Wynand Building is under construction and Dominique, now Roark's wife, enters the site to meet him atop its steel framework.

Background

In 1928, Cecil B. DeMille charged Rand with writing a script for what would become the film Skyscraper. The original story, by Dudley Murphy, was about two construction workers involved in building a New York skyscraper who are rivals for a woman's love. Rand rewrote the story, transforming the rivals into architects. One of them, Howard Kane, was an idealist dedicated to his mission and erecting the skyscraper despite enormous obstacles. The film would have ended with Kane's throwing back his head in victory, standing atop the completed skyscraper. In the end DeMille rejected Rand's script, and the actual film followed Murphy's original idea, but Rand's version contained elements she would later use in The Fountainhead.[1]

David Harriman, who in 1999 edited the posthumous "Journals of Ayn Rand"[2] also noted some elements of "The Fountainhead" already present in the notes for an earlier novel which Rand worked on and never completed. Its protagonist is shown as goaded beyond endurance by a pastor, finally killing him and getting executed. The pastor—considered a paragon of virtue by society but actually a monster—is in many ways similar to Ellsworth Toohey, and the pastor's assassination is reminiscent of Steven Mallory's attempt to kill Toohey.

Rand began The Fountainhead (originally titled Second-Hand Lives) following the completion in 1934 of her first novel, We the Living. While that earlier novel had been based partly on people and events from Rand's experiences, the new novel was to focus on the less-familiar world of architecture. Therefore, she did extensive research to develop plot and character ideas. This included reading numerous biographies and books about architecture,[3] and working as an unpaid typist in the office of architect Ely Jacques Kahn.[4]

Rand's intention was to write a novel that was less overtly political than We the Living, to avoid being "considered a 'one-theme' author".[5] As she developed the story, she began to see more political meaning in the novel's ideas about individualism.[6] Rand also initially planned to introduce each of the four sections with a quote from philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, whose ideas had influenced her own intellectual development. However, she eventually decided that Nietzsche's ideas were too different from her own. She did not place the quotes in the published novel, and she edited the final manuscript to remove other allusions to him.[7]

Rand's work on The Fountainhead was repeatedly interrupted. In 1937, she took a break from it to write a novella called Anthem. She also completed a stage adaptation of We the Living that ran briefly in early 1940.[8] That same year, she also became actively involved in politics, first working as a volunteer in Wendell Willkie's presidential campaign, then attempting to form a group for conservative intellectuals.[9] As her royalties from earlier projects ran out, she began doing freelance work as a script reader for movie studios. When Rand finally found a publisher, the novel was only one-third complete.[10]

Publication history

Although she was a previously published novelist and had a successful Broadway play, Rand had difficulty finding a publisher for The Fountainhead. Macmillan Publishing, which had published We the Living, rejected the book after Rand insisted that they must provide more publicity for her new novel than they did for the first one.[11] Rand's agent began submitting the book to other publishers. In 1938, Knopf signed a contract to publish the book, but when Rand was only a quarter done with manuscript by October 1940, Knopf canceled her contract.[12] Several other publishers rejected the book, and Rand's agent began to criticize the novel. Rand fired her agent and decided to handle submissions herself.[13]

While Rand was working as a script reader for Paramount Pictures, her boss there, Richard Mealand, offered to introduce her to his publishing contacts. He put her in touch with the Bobbs-Merrill Company. A recently hired editor, Archibald Ogden, liked the book, but two internal reviewers gave conflicting opinions about it. One said it was a great book that would never sell; the other said it was trash but would sell well. Ogden's boss, Bobbs-Merrill president D.L. Chambers, decided to reject the book. Ogden responded by wiring to the head office, "If this is not the book for you, then I am not the editor for you." His strong stand got a contract for Rand in December 1941. Twelve other publishers had rejected the book.[14]

Rand's working title for the book was Second Hand Lives, but Ogden pointed out that this emphasized the story's villains. Rand offered The Mainspring as an alternative, but this title had been recently used for another book, so she used a thesaurus and found 'fountainhead' as a synonym.[15]

The Fountainhead was published in May 1943. Initial sales were slow, but as Mimi Reisel Gladstein described it, sales "grew by word-of-mouth, developing a popularity that asserted itself slowly on the best-seller lists."[16] It reached number six on The New York Times bestseller list in August 1945, over two years after its initial publication.[17]

A 25th anniversary edition was issued by New American Library in 1971, including a new introduction by Rand. In 1993, a 50th anniversary edition from Bobbs-Merrill added an afterword by Rand's heir, Leonard Peikoff. By 2008 the novel had sold over 6.5 million copies in English, and it had been translated into several languages.[18]

Characters

Howard Roark

As the protagonist of the book, Roark is an aspiring architect who firmly believes that a person must be a "prime mover" to achieve pure art, not mitigated by others, as opposed to councils or committees of individuals which lead to compromise and mediocrity and a "watering down" of a prime mover's completed vision. He represents the triumph of individualism over the slow stagnation of collectivism. He is eventually arrested for dynamiting a building he designed, the design of which was compromised by other architects brought in to negate his vision of the project. During his trial, Roark delivers a speech condemning "second-handers" and declaring the superiority of prime movers; he prevails and is vindicated by the jury.

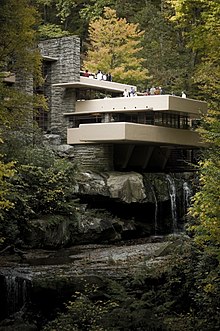

The character of Roark was at least partly inspired by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Rand described the inspiration as limited to "some of his architectural ideas [and] the pattern of his career".[19] She denied that Wright had anything to do with the philosophy expressed by Roark or the events of the plot.[20][21] Rand's denials have not stopped other commentators from claiming stronger connections between Wright and Roark.[21][22] Wright himself equivocated about whether he thought Roark was based on him, sometimes implying that he was, at other times denying it.[23] Wright biographer Ada Louise Huxtable described the "yawning gap" between Wright's philosophy and Rand's, and quoted him declaring, "I deny the paternity and refuse to marry the mother."[24]

Peter Keating

Peter Keating is also an aspiring architect, but is everything that Roark is not. His original inclination was to become an artist, but his opportunistic mother pushes him toward architecture where he might have greater material success. Even by Roark's own admission, Keating does possess some creative and intellectual abilities, but is stifled by his sycophantic pursuit of wealth over morals. His willingness to build what others wish leads him to temporary success. He attends architecture school with Roark, who helps him with some of his less inspired projects. He is subservient to the wills of others: Dominique Francon's father, the architectural establishment, his mother, even Roark himself. Keating is "a man who never could be, but doesn't know it". The one sincere thing in Keating's life is his love for Catherine Halsey, Ellsworth Toohey's niece. Though she offers to introduce Keating to Toohey, he initially refuses despite the fact that such an introduction would help his career. It is the only exception to his otherwise relentless and ruthless ambition, which includes bullying and threatening to blackmail a sick old man and unintentionally causing his death. Although Keating does have a conscience, and often does genuinely feel bad after doing certain things he knows are immoral, he only feels this way in hindsight, and doesn't allow his morals to influence current decision making. Keating's offer to elope with Catherine is his one chance to act on what he believes is his own desire. But, Dominique arrives at that precise moment and offers to marry him for her own reasons, and his acceptance of the offer and betrayal of Catherine ends the potential of romance between them. His acceptance of Dominique's offer of marriage, which would help his career far more than a marriage with Catherine, is a quintessential example of his failure to stand up for his own convictions.

Dominique Francon

Dominique Francon is the heroine of The Fountainhead, described by Rand as "the woman for a man like Howard Roark."[25] For most of the novel, the character operates from what Rand later described as "a very mistaken idea about life."[26] Dominique is the daughter of Guy Francon, a highly successful but creatively inhibited architect. She is a thorn in the flesh of her father and causes him much distress for her works criticizing the architectural profession's mediocrity. Peter Keating is employed by her father, and her intelligence, insight and observations are above his. It is only through Roark that her love of adversity and autonomy meets a worthy equal. These strengths are also what she initially lets stifle her growth and make her life miserable. She begins thinking that the world did not deserve her sincerity and intellect, because the people around her did not measure up to her standards. She starts out punishing the world and herself for all the things about man which she despises, through self-defeating behavior. She initially believes that greatness, such as Roark's, is doomed to fail and will be destroyed by the 'collectivist' masses around them. She eventually joins Roark romantically, but before she can do this, she must learn to join him in his perspective and purpose.

The character has provoked varied reactions from commentators. Chris Matthew Sciabarra called her "one of the more bizarre characters in the novel."[27] Mimi Reisel Gladstein called her "an interesting case study in perverseness"[28] Tore Boeckmann described her as a character with "mixed premises", some of which were mistaken, and saw her actions as a logical representation of how her conflicting ideas might play out.[29]

Gail Wynand

Gail Wynand is a wealthy newspaper mogul who rose from a destitute childhood in the ghettoes of New York City to control much of the city's print media. While Wynand shares many of the character qualities of Roark, his success is dependent upon his ability to pander to public opinion, a flaw which eventually leads to his downfall. In her journals Rand described Wynand as "the man who could have been" a heroic individualist, contrasting him to Roark, "the man who can be and is".[30] Some elements of Wynand's character were inspired by real-life newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst,[31] including Hearst's mixed success in attempts to gain political influence.[32] Wynand is a tragic figure who ultimately fails in his attempts to wield power, losing his newspaper, his wife, and his friendship with Roark.[33] The character has been interpreted as a representation of Nietzsche's "master morality",[34] and his tragic nature illustrates Rand's rejection of Nietzsche's philosophy.[35] In Rand's view, a person like Wynand, who seeks power over others, is just as much a "second-hander" as a conformist like Keating.[36]

Ellsworth Toohey

Ellsworth Monkton Toohey, who writes a popular art criticism column, is Roark's antagonist. Toohey is Rand's personification of evil, the most active and self-aware villain in any of her novels.[37] Toohey is a socialist, and represents the spirit of collectivism more generally. He styles himself as representative of the will of the masses, but his actual desire is for power over others.[38] He controls individual victims by destroying their sense of self-worth, and seeks broader power (over "the world", as he declares to Keating in a moment of candor) by promoting the ideals of ethical altruism and a rigorous egalitarianism that treats all people and achievements as equally valuable, regardless of their true value.[39] As one reviewer described his approach:

Aiming at a society that shall be "an average drawn upon zeroes," he knows exactly why he corrupts Peter Keating, and explains his methods to the ruined young man in a passage that is a pyrotechnical display of the fascist mind at its best and its worst; the use of the ideal of altruism to destroy personal integrity, the use of humor and tolerance to destroy all standards, the use of sacrifice to enslave.[40]

His biggest threat is the strength of the individual spirit embodied by Roark.[41]

Rand used her memory of the British democratic socialist Harold Laski to help her imagine what Toohey would do in a given situation. New York intellectuals Lewis Mumford and Clifton Fadiman also contributed inspirations for the character.[42]

Minor characters

- Henry Cameron: Roark's architect mentor and employer

- The Dean: The dean of the Stanton Institute of Technology architecture school

- Guy Francon: Dominique's father and Keating's employer and business partner

- Catherine Halsey: Keating's fiancee and Toohey's niece

- Austen Heller: An individualistic thinker who hires Roark and becomes one of his biggest allies.

- Lucius Heyer: The business partner of Guy Francon, who is indirectly killed by Keating's attempts at manipulation.

- Mrs. Keating: Keating's overbearing and manipulative mother

- Steven Mallory: A disillusioned sculptor who tries to kill Toohey but later regains his confidence with the help of Roark

- Alvah Scarret: Wynand's editor-in-chief

- John Erik Snyte: An employer of Roark's who uses a group of five designers to create a final sketch

Main themes

Individualism

Rand indicated that the primary theme of The Fountainhead was "individualism versus collectivism, not in politics but within a man's soul."[43] Apart from scenes such as Roark's courtroom defense of the American concept of individual rights, she avoided direct discussion of political issues. As historian James Baker described it, "The Fountainhead hardly mentions politics or economics, despite the fact that it was born in the 1930s. Nor does it deal with world affairs, although it was written during World War II. It is about one man against the system, and it does not permit other matters to intrude."[44]

Architecture

Rand dedicated The Fountainhead to her husband, Frank O'Connor, and to architecture. She chose architecture for the analogy it offered to her ideas, especially in the context of the ascent of modern architecture. It provided an appropriate vehicle to concretize her beliefs that the individual is of supreme value, the "fountainhead" of creativity, and that selfishness, properly understood as ethical egoism, is a virtue.

Peter Keating and Howard Roark are character foils. Keating practices in the historical eclectic and neo-classic mold, even when the building's typology is a skyscraper. He follows and pays respect to old traditions. He accommodates the changes suggested by others, mirroring the eclectic directions, and willingness to adapt, current at the turn of the twentieth century. Roark searches for truth and honesty and expresses them in his work. He is uncompromising when changes are suggested, mirroring modern architecture's trajectory from dissatisfaction with earlier design trends to emphasizing individual creativity. Roark's individuality eulogizes modern architects as uncompromising and heroic.

The Fountainhead has been cited by numerous architects as an inspiration for their work. Architect Fred Stitt, founder of the San Francisco Institute of Architecture, dedicated a book to his "first architectural mentor, Howard Roark".[45] Nader Vossoughian has written that "The Fountainhead... has shaped the public's perception of the architectural profession more than perhaps any other text over this last half-century."[46] According to renowned architectural photographer Julius Shulman, it was Rand's work that "brought architecture into the public's focus for the first time," and he believes that The Fountainhead was not only influential among 20th century architects, it "was one, first, front and center in the life of every architect who was a modern architect."[47]

Reception and legacy

Contemporary reception

The Fountainhead polarized critics and received mixed reviews upon its release.[48] The New York Times' review of the novel named Rand "a writer of great power" who writes "brilliantly, beautifully and bitterly," and it stated that she had "written a hymn in praise of the individual... you will not be able to read this masterful book without thinking through some of the basic concepts of our time."[40] Benjamin DeCasseres, a columnist for the New York Journal-American, wrote of Roark as "an uncompromising individualist" and "one of the most inspiring characters in modern American literature." Rand sent DeCasseres a letter thanking him for explaining the book's individualistic themes when many other reviewers did not.[49] There were other positive reviews, but Rand dismissed many of them as either not understanding her message or as being from unimportant publications.[48] A number of negative reviews focused on the length of the novel,[50] such as one that called it "a whale of a book" and another that said "anyone who is taken in by it deserves a stern lecture on paper-rationing." Other negative reviews called the characters unsympathetic and Rand's style "offensively pedestrian."[48]

The year 1943 also saw the publication of The God of the Machine by Isabel Paterson and The Discovery of Freedom by Rose Wilder Lane. Rand, Lane and Paterson have been referred to as the founding mothers of the American libertarian movement with the publication of these works.[51] Journalist John Chamberlain, for example, credits these works with his final "conversion" from socialism to what he called "an older American philosophy" of libertarian and conservative ideas.[52]

Responses to the rape scene

One of the most controversial elements of the book is the rape scene between Roark and Dominique.[53] Feminist critics have attacked the scene as representative of an anti-feminist viewpoint in Rand's works that makes women subservient to men.[54] Susan Brownmiller, in her 1975 work Against Our Will, denounced what she called "Rand's philosophy of rape", for portraying women as wanting "humiliation at the hands of a superior man." She called Rand "a traitor to her own sex."[55] Susan Love Brown said the scene presents Rand's view of sex as "as an act of sadomasochism and of feminine subordination and passivity".[56] Barbara Grizzuti Harrison suggested women who enjoy such "masochistic fantasies" are "damaged" and have low self-esteem.[57] While Rand scholar Mimi Reisel Gladstein found elements to admire in Rand's female protagonists, she said that readers who have "a raised consciousness about the nature of rape" would disapprove of Rand's "romanticized rapes."[58]

Rand denied that what happened in the scene was actually rape, referring to it as "rape by engraved invitation"[53] because Dominique wanted and "all but invited" the act, citing among other things the conversation after Dominique scratches the marble slab in her bedroom in order to invite Roark to repair it.[59] A true rape, Rand said, would be "a dreadful crime."[60] Defenders of the novel have agreed with this interpretation. In an essay specifically explaining this scene, Andrew Bernstein wrote that although there is much "confusion" about it, the descriptions in the novel provide "conclusive" evidence that "Dominique feels an overwhelming attraction to Roark" and "desires desperately to sleep with" him.[61] Individualist feminist Wendy McElroy said that while Dominique is "thoroughly taken," there is nonetheless "clear indication that Dominique not only consented," but also enjoyed the experience.[62] Both Bernstein and McElroy saw the interpretations of feminists such as Brownmiller as being based in a false understanding of sexuality.[63]

Rand's posthumously published working notes for the novel, which were not known at the time of her debate with feminists, indicate that when she started working on the book in 1936 she conceived of Roark's character that "were it necessary, he could rape her and feel justified."[64]

Cultural influence

The Fountainhead has continued to have strong sales throughout the last century into the current one, and has been referenced in a variety of popular entertainment, including movies, television series and other novels.[66] Despite its popularity, it has received relatively little ongoing critical attention.[67][68] Assessing the novel's legacy, philosopher Douglas Den Uyl described The Fountainhead as relatively neglected compared to her later novel, Atlas Shrugged, and said, "our problem is to find those topics that arise clearly with The Fountainhead and yet do not force us to read it simply through the eyes of Atlas Shrugged."[67]

Among critics who have addressed it, some consider The Fountainhead to be Rand's best novel,[69][70][71] such as philosopher Mark Kingwell, who described The Fountainhead as "Rand's best work—which is not to say it is good."[72] A Village Voice columnist has called it "blatantly tendentious" and described it as containing "heavy-breathing hero worship."[73]

The book has a particular appeal to young people, an appeal that led historian James Baker to describe it as "more important than its detractors think, although not as important as Rand fans imagine."[70] Allan Bloom has referred to the novel as being "hardly literature," one having a "sub-Nietzschean assertiveness [that] excites somewhat eccentric youngsters to a new way of life." However, he also writes that when he asks his students which books matter to them, there is always someone influenced by The Fountainhead.[74] Journalist Nora Ephron wrote that she had loved the novel when she was 18 but admitted that she "missed the point," which she suggested is largely subliminal sexual metaphor. Ephron wrote that she decided upon re-reading that "it is better read when one is young enough to miss the point. Otherwise, one cannot help thinking it is a very silly book."[75] Architect David Rockwell said that the film adaptation influenced his interest in architecture and design, and that many architecture students at his university named their dogs Roark as a tribute to the protagonist of the novel and film.[76]

Pop culture references

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

In the Barney Miller episode "The Architect" (1980), architect Howard Speer is arrested for vandalizing his own building, protesting unwanted changes to his original design. He refers to the building as a "Cortlandt". Sgt. Dietrich overhears this and warns Barney that Speer has planted bombs in the building. The explosion is crafted like a controlled demolition, eliciting a round of applause from the bomb squad.

In the film Dirty Dancing (1987) Baby confronts Robbie to pay for Penny's abortion. Robbie refuses to take responsibility and says "Some people count and some people don't" and then hands Baby a used paperback copy of The Fountainhead saying, "Read it. I think it's a book you'll enjoy, but make sure you return it; I have notes in the margin."[77][78]

In Episode 7.7 "Mazel Tov, Dummies!" of 30 Rock, Jack reads a passage from The Fountainhead instead of the Bible.

In the film A Scanner Darkly (2006) the character Charles Freck unsuccessfully attempts suicide while wishing to be found dead in his apartment with his body gripping a copy of The Fountainhead. Due to drug-induced incoherence, he illogically believes that such an action will "indict the system and allow his death to achieve something".

In Episode 20.20 "Four Great Women and a Manicure" of The Simpsons, Marge takes Lisa to a salon for her first manicure, prompting a debate as to whether a woman can simultaneously be smart, powerful and beautiful by telling tales to one another. In the final tale, Maggie is depicted as "Maggie Roark," representing Howard Roark from The Fountainhead.

In The Perks of Being a Wallflower, The Fountainhead is one of several books that Bill assigns Charlie to read.[79]

In Season 2 Episode 13 "A-Tisket A-Tasket" of Gilmore Girls, Rory encourages Jess to read The Fountainhead once more, saying that it is classic and that no one could write a forty page monologue the way she (Ayn Rand) could.

In Season 3 Episode 12 "Par Avion" of ABC's Lost, James "Sawyer" Ford is seen reading "The Fountainhead" as another character, Charlie Pace, is reading an SOS letter that he and Claire Littleton intend on attaching to a seagull with hope for rescue.

In Woody Allen's To Rome with Love, Hayley (Alison Pill) talks about her desire to sleep with Howard Roark to impress her friend's boyfriend.

In Season 2, Episode 3 of Elementary, the book was found misplaced at the crime scene where Detective Marcus Bell remarks that "half the college kids in New York have that book". Sherlock Holmes then describes Ayn Rand as "The philosopher-in-chief to the intellectually bankrupt".

In the Frasier episode Frasier's Edge, Dr. Frasier Crane says to his mentor that his interest in psychiatry was sparked the day an older boy threw his copy of The Fountainhead under a bus.[80]

In the film Identity Thief (2013), Sandy Patterson's boss Harold Cornish says to him: "I'll get you a copy of The Fountainhead. Then you’ll see why this is good for everybody." after questioning the hefty bonuses the higher-ups will be receiving.

In Gene Roddenberry's Andromeda, planet Fountainhead is the historical homeworld of the Nietzschean people, orbited by Ayn Rand station. In the episode The Banks of the Lethe, Tyr throws a copy of The Fountainhead to Captain Hunt.

Adaptations

Illustrated version

In 1945, Rand was approached by King Features Syndicate about having a condensed, illustrated version of the novel published for syndication in newspapers. Rand agreed, provided that she could oversee the editing and approve the proposed illustrations of her characters, which were provided by Frank Godwin. The 30-part series began on December 24, 1945, and ran in over 35 newspapers.[81]

Film version

In 1949, Warner Brothers released a film based on the book, starring Gary Cooper as Howard Roark, Patricia Neal as Dominique Francon, Raymond Massey as Gail Wynand, and Kent Smith as Peter Keating. The film was directed by King Vidor. The Fountainhead grossed $2.1 million, $400,000 less than its production budget.[82] However, sales of the novel increased as a result of interest spurred by the film.[83] In letters written at the time, the author's reaction to the film was positive, saying "The picture is more faithful to the novel than any other adaptation of a novel that Hollywood has ever produced"[84] and "It was a real triumph."[85] However, she displayed a more negative attitude towards it later, saying that she "disliked the movie from beginning to end", and complaining about its editing, acting and other elements.[86] As a result of this film, Rand said that she would never sell any of her novels to a film company that did not allow her the right to pick the director and screenwriter as well as edit the film, as she did not want to encounter the same production problems that occurred on this film.[87]

Theatrical version

In June 2014, an adaptation for the stage (in Dutch) was presented at the Holland Festival, directed by Ivo van Hove, with Ramsey Nasr as Howard Roark.[88] The production subsequently went on tour, appearing in Barcelona in early July 2014,[89] and then at the Festival d'Avignon later that month.[90]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 65, 441; Eyman, Scott (2010). Empire of Dreams: The Epic Life of Cecil B. DeMille. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-7432-8955-9. OCLC 464593099.

- ^ "Journals of Ayn Rand", edited by David Harriman, Penguin, 1999, Ch. 3

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 41

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 11

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 43

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 69

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 87; Milgram, Shoshana. "The Fountainhead from Notebook to Novel". in Mayhew 2006, pp. 13–17

- ^ Britting 2004, pp. 54–56

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 54–66

- ^ Branden 1986, p. 171

- ^ Branden 1986, p. 155

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 52

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 68

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 80; Branden 1986, pp. 170–171; Heller 2009, p. 186. Heller notes that the rejections included Macmillan and Knopf, who had expressed some interest in publishing the book but eventually rejected it over contractual issues.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 80

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 12

- ^ "Timeline of Ayn Rand's Life and Career". Ayn Rand Institute. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, p. 122

- ^ Rand 2005, p. 190

- ^ Berliner, Michael S. "Howard Roark and Frank Lloyd Wright". In Mayhew 2006, pp. 48–50

- ^ a b Reidy, Peter. "Frank Lloyd Wright And Ayn Rand". The Atlas Society. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- ^ Berliner, Michael S. "Howard Roark and Frank Lloyd Wright". In Mayhew 2006, pp. 42–44

- ^ Berliner, Michael S. "Howard Roark and Frank Lloyd Wright". In Mayhew 2006, pp. 47–48

- ^ Huxtable, Ada Louise (2008) [2004]. Frank Lloyd Wright: A Life. New York: Penguin. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-14-311429-1. OCLC 191929123.

- ^ Rand 1997, p. 89

- ^ Rand 1995, p. 341

- ^ Sciabarra 1995, p. 107

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 41

- ^ Boeckmann, Tore. "Aristotle's Poetics and The Fountainhead. In Mayhew 2006, pp. 158, 164

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 44; Heller 2009, pp. 117–118

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 44; Johnson 2005, p. 44; Berliner, Michael S. "Howard Roark and Frank Lloyd Wright". In Mayhew 2006, p. 57

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 44–45

- ^ Gladstein 1999, pp. 52–53

- ^ Hicks 2009, p. 267

- ^ Gotthelf 2000, p. 14; Heller 2009, p. 117; Merrill 1991, pp. 47–50

- ^ Smith, Tara. "Unborrowed Vision: Independence and Egoism in The Fountainhead". In Mayhew 2006, pp. 291–293; Baker 1987, pp. 102–103; Den Uyl 1999, pp. 58–59

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 62; Den Uyl 1999, pp. 54–55; Minsaas, Kirsti. "The Stylization of Mind in Ayn Rand's Fiction". In Thomas 2005, p. 187

- ^ Baker 1987, p. 52; Gladstein 1999, p. 62

- ^ Den Uyl 1999, pp. 54–56; Sciabarra 1995, pp. 109–110

- ^ a b Pruette 1943

- ^ Merrill 1991, p. 52

- ^ Berliner, Michael. "Howard Roark and Frank Lloyd Wright". In Mayhew 2006, p. 57; Johnson 2005, pp. 44–45

- ^ Rand 1997, p. 223

- ^ Baker 1987, p. 51

- ^ Branden 1986, p. 420

- ^ Vossoughian, Nader. "Ayn Rand's 'Heroic' Modernism: Interview with Art and Architectural Historian Merrill Schleier". agglutinations.com/. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- ^ McConnell 2010, pp. 84–85

- ^ a b c Berliner, Michael S. "The Fountainhead Reviews", in Mayhew 2006, pp. 77–82

- ^ Rand 1995, p. 75

- ^ Gladstein 1999, pp. 117–119

- ^ Powell, Jim (May 1996). "Rose Wilder Lane, Isabel Paterson, and Ayn Rand: Three Women Who Inspired the Modern Libertarian Movement". The Freeman: Ideas on Liberty. 46 (5): 322. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ John Chamberlain, A Life with the Printed Word, Regnery, 1982, p.136.

- ^ a b Burns 2009, p. 86; Den Uyl 1999, p. 22

- ^ Den Uyl 1999, p. 22

- ^ Brownmiller, Susan (1975). Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-22062-4.. Reprinted in Gladstein & Sciabarra 1999, pp. 63–65

- ^ Brown, Susan Love. "Ayn Rand: The Woman Who Would Not Be President". In Gladstein & Sciabarra 1999, p. 289

- ^ Harrison, Barbara Grizzuti. "Psyching Out Ayn Rand". In Gladstein & Sciabarra 1999, pp. 74–75

- ^ Gladstein 1999, pp. 27–28

- ^ Rand 1995, p. 631

- ^ Rand 1995, p. 282

- ^ Bernstein, Andrew. "Understanding the 'Rape' Scene in The Fountainhead". In Mayhew 2006, pp. 201–203

- ^ McElroy, Wendy. "Looking Through a Paradigm Darkly". In Gladstein & Sciabarra 1999, pp. 163–164

- ^ Bernstein, Andrew. "Understanding the 'Rape' Scene in The Fountainhead". In Mayhew 2006, p. 207; McElroy, Wendy. "Looking Through a Paradigm Darkly". In Gladstein & Sciabarra 1999, pp. 162–163

- ^ "Journals of Ayn Rand", entry for February 9, 1936.

- ^ Cohen, Arianne (May 21, 2006). "The Soda Fountainhead". New York.

- ^ Sciabarra 2004, pp. 3–5; Burns 2009, pp. 282–283

- ^ a b Den Uyl 1999, p. 21

- ^ Hornstein, Alan D. (1999). "The Trials of Howard Roark". Legal Studies Forum. 23 (4): 431.

- ^ Cullen-DuPont, Kathryn (2000). Encyclopedia of Women's History in America (2nd ed.). New York: Infobase Publishing. p. 211. ISBN 0-8160-4100-8.

- ^ a b Baker 1987, p. 57

- ^ Merrill 1991, p. 45

- ^ Kingwell, Mark (2006). Nearest Thing to Heaven: The Empire State Building and American Dreams. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-300-10622-0.

- ^ Hoberman, J. (February 17, 1998). "Crazy for You". The Village Voice. Vol. 43, no. 7. p. 111.

- ^ Bloom, Allan (1987). The Closing of the American Mind. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 62. ISBN 0-671-65715-1. OCLC 17820784.

- ^ Ephron, Nora (1970). "The Fountainhead Revisited". Wallflower at the Orgy. New York: Viking. p. 47.

- ^ Hofler, Robert (2009). "The Show People". Variety's "the movie that changed my life": 120 celebrities pick the films that made a difference (for better or worse). Da Capo Press. p. 163.

- ^ Tom Geoghega (17 August 2012). "Ayn Rand: Why is she so popular?". BBC News Magazine. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ^ "IMDB: Memorable quotes for Dirty Dancing".

- ^ Chbosky, S. (2012). The Perks of Being a Wallflower. MTV Books. p. 165. ISBN 9781451696196. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ "Frasier's Edge". The Frasier Archives. KACL780.net. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ^ Sciabarra 2004, p. 6

- ^ Hoberman, J (2011). "The ministry of truth, justice and the American way, 1948–50". An Army of Phantoms: American Movies and the Making of the Cold War. The New Press. pp. 96–98. ISBN 1-59558-005-0.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, p. 95

- ^ Rand 1995, p. 445

- ^ Rand 1995, p. 419

- ^ Britting 2004, p. 71

- ^ McConnell 2010, p. 262

- ^ "The Fountainhead: World Premier". Holland Festival. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ "The Fountainhead in Barcelona". Toneelgroep Amsterdam. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ Candoni, Christopher (July 16, 2014). "The Fountainhead: Ivo Van Hove Architecte d'un Grand Spectacle" (in French). Toute la Culture. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

Works cited

- Baker, James T. (1987). Ayn Rand. Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-7497-1. OCLC 14933003.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Branden, Barbara (1986). The Passion of Ayn Rand. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company. ISBN 0-385-19171-5. OCLC 12614728.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Britting, Jeff (2004). Ayn Rand. Overlook Illustrated Lives. New York: Overlook Duckworth. ISBN 1-58567-406-0. OCLC 56413971.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Burns, Jennifer (2009). Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532487-7. OCLC 313665028.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Den Uyl, Douglas J. (1999). The Fountainhead: An American Novel. Twayne's Masterwork Studies. New York: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-7932-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gladstein, Mimi Reisel (1999). The New Ayn Rand Companion. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30321-5. OCLC 40359365.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gladstein, Mimi Reisel (2009). Ayn Rand. Major Conservative and Libertarian Thinkers series. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-4513-1. OCLC 319595162.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gladstein, Mimi Reisel; Sciabarra, Chris Matthew, eds. (1999). Feminist Interpretations of Ayn Rand. Re-reading the Canon. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01830-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Gotthelf, Allan (2000). On Ayn Rand. Wadsworth Philosophers Series. Belmont, California: Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 0-534-57625-7. OCLC 43668181.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Heller, Anne C. (2009). Ayn Rand and the World She Made. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51399-9. OCLC 229027437.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hicks, Stephen R.C. (Spring 2009). "Egoism in Nietzsche and Rand". The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 10 (2): 249–291.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Johnson, Donald Leslie (2005). The Fountainheads: Wright, Rand, the FBI and Hollywood. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-1958-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mayhew, Robert, ed. (2006). Essays on Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. ISBN 0-7391-1577-4. OCLC 70707828.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McConnell, Scott (2010). 100 Voices: An Oral History of Ayn Rand. New York: New American Library. ISBN 978-0-451-23130-7. OCLC 555642813.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Merrill, Ronald E. (1991). The Ideas of Ayn Rand. La Salle, Illinois: Open Court Publishing. ISBN 0-8126-9157-1. OCLC 23254190.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pruette, Lorine (May 16, 1943). "Battle Against Evil". The New York Times. p. BR7.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Reprinted in McGrath, Charles, ed. (1998). Books of the Century. New York: Times Books. pp. 135–136. ISBN 0-8129-2965-9. - Rand, Ayn (1995). Berliner, Michael S (ed.). Letters of Ayn Rand. New York: Dutton. ISBN 0-525-93946-6. OCLC 31412028.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rand, Ayn (1997). Harriman, David (ed.). Journals of Ayn Rand. New York: Dutton. ISBN 0-525-94370-6. OCLC 36566117.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rand, Ayn (2005). Mayhew, Robert (ed.). Ayn Rand Answers, the Best of Her Q&A. New York: New American Library. ISBN 0-451-21665-2. OCLC 59148253.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (1995). Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01440-7. OCLC 31133644.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (Fall 2004). "The Illustrated Rand" (PDF). The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 6 (1): 1–20.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thomas, William, ed. (2005). The Literary Art of Ayn Rand. Poughkeepsie, New York: The Objectivist Center. ISBN 1-57724-070-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- McGann, Kevin (1978). "Ayn Rand in the Stockyard of the Spirit". In Peary, Gerald; Shatzkin, Roger (eds) (eds.). The Modern American Novel and the Movies. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing. ISBN 0-8044-2682-1.

{{cite book}}:|editor2-first=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Cox, Stephen (2005). "The Literary Achievement of The Fountainhead". In Thomas, William (ed.). The Literary Art of Ayn Rand. Poughkeepsie, New York: The Objectivist Center. ISBN 1-57724-070-7.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)

Foreign language translations

- Czech: Zdroj, published by Berlet, 2000.

- Marathi: by Prof. Mugdha Karnik, University of Mumbai. Diamond Publications, 2013.