Yellow Peril

Yellow Peril (sometimes Yellow Terror) was a color metaphor for race, namely the theory that Asian peoples are a mortal danger to the rest of the world. In the words of the American historian John W. Dower: "the vision of the menace from the East was always more racial rather than national. It derived not from concern with any one country or people in particular, but from a vague and ominous sense of the vast, faceless, nameless yellow horde: the rising tide, indeed, of color."[1] Dower described "the core imagery of apes, lesser men, primitives, children, madmen, and beings who possessed special powers", which the Yellow Peril theory associated with Asians.[1] The British Sinologist Leung Wing Fai wrote that: "The phrase yellow peril (sometimes yellow terror or yellow spectre), coined by Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, in the 1890s, after a dream in which he saw the Buddha riding a dragon threatening to invade Europe, blends western anxieties about sex, racist fears of the alien other, and the Spenglerian belief that the West will become outnumbered and enslaved by the East".[2] The term Yellow Peril was coined by German Emperor Wilhelm II in 1895, but the theory that Asian peoples represented a menace to the West originated in the late nineteenth century with Chinese immigrants as coolie slaves or laborers to various Western countries, notably the United States. It was later associated with the Japanese during the mid-20th century, due to Japanese military expansion, and eventually extended to all Asians of East and Southeast Asian descent.

The term refers to perceptions regarding the skin color of East Asians, the fear that the mass immigration of Asians threatened white wages and standards of living, and the fear that they would eventually take over and destroy western civilization, replacing it with their ways of life and values.

The term also refers to the fear and or belief that East Asian societies would attack and wage wars with western societies and eventually wipe them out and lead to their total annihilation whether it be their societies, people, ways of life, history, and or cultural values.

Origins

In the late 19th century, Chinese immigration to the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada sparked a racist backlash against people who were willing to work hard for less than whites, and who were so different in appearance, language and culture from whites. In 1870, the French writer Ernest Renan warned of the danger from the East to the West, through in this case Renan primarily meant Russia.[3] In the 1870s, working-class whites in California demanded that the U.S government stop the immigration of "filthy yellow hordes" from China who were supposedly responsible for the economic depression by taking away jobs from white Amerians.[1] Horace Greeley, the editor of the New-York Tribune newspaper wrote in an editorial in support of Chinese exclusion that: "The Chinese are uncivilized, unclean, and filthy beyond all conception without any of the higher domestic or social relations; lustful and sensual in their dispositions; every female is a prostitute of the basest order.".[1] Widespread dislike of the Chinese led to the Los Angeles pogrom in 1871 where 18 Chinese immigrants were killed by a white mob. The pressure to ban Chinese immigration led to the U.S. Congress passing the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.[1]

Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany coined the phrase "Yellow Peril" (German: gelbe Gefahr) in September 1895.[4] The Kaiser had an illustration of this title — depicting the Archangel Michael as an allegorical Germany leading the European powers against an "Asiatic threat" represented by a golden Buddha — hung in all ships of the Hamburg America Line.[3] It was ostensibly designed by the Kaiser himself.[5] The British historian John Röhl described Wilhelm's sketch which inspired the Yellow Peril painting as portraying European nations as "...prehistoric warrior-goddesses being led by the Archangel Michael against the "yellow peril" (represented by a Buddha) from the East".[6][7] The painting was inspired by a dream that Wilhelm had, which Wilhelm took to be a prophecy of the coming, apocalyptic great "race war" between Europe and Asia which would decide the future of the 20th century.[6] Wilhelm was a fanatical white supremacist who loathed Asian peoples, believed that it only a time before a "race war" began, and being an extremely egoistical man saw himself as the natural leader of the "white race" in the coming war against the "yellow peril".[8] After his dream, Wilhelm drew a sketch and then had his count painter Hermann Knackfuss turned it into the Yellow Peril painting.[3] Wilhelm was so impressed that he sent copies of it out as his Christmas presents in 1895.[3] The former Chancellor Bismarck received the painting as a present from the Kaiser, and through he did not quite understand what the painting was supposed to be about, hung up in a prominent place at his estate.[3] The painting was very popular in its day, and was reprinted in the New York Times in 1898 under the title The Yellow Peril.[3]

The Height of the Yellow Peril Hysteria

Even before his dream, Wilhelm was obsessed with the supposed danger represented by Asian peoples towards the "white race", writing in an letter to his cousin Emperor Nicholas II of Russia in April 1895: "It is clearly the great task of the future for Russia to cultivate the Asian continent and defend Europe from the inroads of the Great Yellow Race".[6] The British historian James Palmer wrote that:

"The 1890s had spawned in the West the spectre of the "Yellow Peril", the rise to dominance of the Asian peoples. The evidence cited was Asian population growth, immigration to the West (America and Australia in particular), and increased Chinese settlement along the Russian border. These demographic and political fears were accompanied by a vague and ominous dread of the mysterious powers supposedly possessed by the initiates of Eastern religions. There is a striking German picture of the 1890s, depicting the dream that inspired Kaiser Wilhelm II to coin the term "Yellow Peril", that shows the union of these ideas. It depicts the nations of Europe, personified as heroic, but vulnerable female figures guarded by the Archangel Michael, gazing apprehensively towards a dark cloud of smoke in the East, in which rests an eerily calm Buddha, wreathed in flame...Combined with this was a sense of the slow sinking of the Abendland, the "Evening Land" of the West. This would be put most powerfully by thinkers such as Oswald Spengler in The Decline of the West (1918) and the Prussian philosopher Moeller van den Bruck, a Russian-speaker obsessed with the coming rise of the East. Both called for Germany to join the "young nations" of Asia-through the adoption of such supposedly Asiatic practices as collectivism, "inner barbarism", and despotic leadership. The identification of Russia with Asia would eventually overwhelm such sympathies, instead leading to a more-or-less straightforward association of Germany with the values of "the West", against the "Asiatic barbarism" of Russia. This was most obvious during the Nazi era, when virtually every piece of anti-Russian propaganda talked of the "Asiatic millions" or "Mongolian hordes", which threatened to overrun Europe, but the identification of the Russians as Asian-and especially as Mongolian-continued well into the Cold War era."[9]

The idea of the "Yellow Peril" became especially popular in Germany from the 1890s onward, and often colored German perceptions of Russia, which many Germans viewed as either a half-Asian or entirely Asian nation well into the 20th century.[10] Folk memories of the destructive Mongol conquests under Genghis Khan often led to the term Mongol being used as a shorthand for the alleged Asian culture of extreme cruelty and supposed insatiable appetite for conquest, and as such all it was common to label all Asians as "Mongols".[11] In particular, Genghis Khan was invoked as the personification of Asian inhumanity; the utterly ruthless leader of the pitiless, merciless and extremely efficient killing machine that was said to be the Mongol horde.[11] Such was the identification of Asians with cruelty that German authors influenced by the racial theories so popular in Germany at the time often explained the icy, relentless, cruel fanaticism of Vladimir Lenin as due to his "Mongol blood"-a reference to the fact that Lenin's great-grandmother was a Kalmyk.[12]

For their part, many Russians shared the fear of the "Yellow Peril". General Aleksey Kuropatkin, the Russian Minister of War and the leader of a clique at the Russian court committed to the idea of Russian expansion in Asia portrayed the rising power of Japan in the early 20th century and Japanese imperialist ambitions in Manchuria and Korea (both of which Kuropatkin coveted for Russia) as the first step of the "Yellow Peril" that Russia had to stop.[13] Kuroatkin's often justified his imperialist plans for East Asia as part of Russia's "mission" to stop the "Yellow Peril". During the Russian-Japanese war, which was fought mostly in Manchuria, Russian troops routinely looted and burned Chinese villages, raped the women and killed all who resisted or who were just in the way.[14] The Russian justification for all this was that Chinese civilians, being Asian, were helping their fellow Asians the Japanese inflict defeats on the Russians, and therefore deserved to be punished.[15] Even after Russia's defeat at the hands of Japan, Kuropatkin remained committed to a forward policy in the Far East, albeit a less aggressive than before 1904. Kuropatkin wrote in 1913 that "in the future, a major global war could flare up between the yellow race and the white...For this purpose, Russia must occupy north Manchuria and Mongolia...Only then will Mongolia be harmless".[16] Kuropatkin's remarks about rendering Mongolia "harmless" partly reflected Russian folk memories of the Mongol conquest of Russia in the 13th century, and partly reflected his fear of the vast Chinese immigration into Inner Mongolia and Manchuria which was to soon to give both regions a Han majority, which he viewed as "the first blow of the yellow race against the white".[16]

On 27 July 1900, Wilhelm gave a wildly racist speech in Bremerhaven to German soldiers departing to China to suppress the Boxer Uprising, calling on them to commit atrocities against Chinese civilians and to behave like "Huns".[7] In the Hunnenrede (Hun speech), Wilhelm declared:

"When you came before the enemy, you must defeat him, pardon will not be given, prisoners will not be taken! Whoever falls into your hands will fall to your sword! Just as a thousand years ago the Huns under their King Attila made a name for themselves with their ferocity which tradition still recalls; so may the name of Germany become known in China in such a way that no Chinaman will ever dare look a German in the eye even with a squint!".[17]

In 1901, the White Australia policy was adopted. Australia's official World War One historian Charles Bean defined the intentions of the policy as "a vehement effort to maintain a high Western standard of economy, society and culture (necessitating at that stage, however it might be camouflaged, the rigid exclusion of Oriental peoples)."[18]

Through very popular, the Yellow Peril theory was not universally accepted. The French writer Anatole France wrote that the Yellow Peril ideology was the sort of thing one would expect from the racist, hate-filled mind of the Kaiser, and inverting the entire premise of the Yellow Peril, argued in an essay that given the tendency of European nations to gobble up other people's countries in Asia and Africa that it was the "White Peril" that was the real threat to the rest of the world.[3] Another critic was an American who in 1898 published an essay entitled "The Bogey of the Yellow Peril" argued that the entire Yellow Peril theory was just racist hysteria.[3]

In the early years of the 20th century, Wilhelm continued to warn anyone who would listen about the Yellow Peril. In a 1907 letter to Nicholas II, Wilhelm wrote that British newspapers "had for the first time used the term Yellow Peril from my picture, which is coming true!" (emphasis in the original).[19] In the same letter, Wilhelm claimed that 10, 000 Japanese soldiers had arrived in Mexico with the aim of seizing the Panama Canal, and that the Japanese "were going in for the whole of Asia, carefully preparing their blows, and against the White Race in General! Remember my picture, it's coming true!".[19] Also in 1907, Wilhelm sent a message to American president Theodore Roosevelt, predicating the coming "race war", and offered to sent German troops to protect the West Coast of the United States from the Japanese, who Wilhelm claimed would soon be invading the U.S; President Roosevelt politely refused the offer.[19] In October 1914, a group of 57 noted German professors signed an appeal to "civilized people of the world", which portrayed Germany as the victim of Allied aggression and contained the following passage:

"In the East the land is soaked with the blood of women and children butchered by the Russian hordes, and in the West our soldiers are being ripped apart by dumdum bullets. The nations with the least right to call themselves the defenders of European civilization are those which have allied themselves with Russians and Serbs and offer the world the degrading spectacle of inciting Mongols and Negroes to attack the white race".[20]

The reference to "Mongols and Negroes" was to the various Asian peoples serving in the Imperial Russian Army and to Africans in the French Army. Wilhelm changed his mind after his abdication in World War I, saying that he should not have bothered to warn Europe of the Yellow Peril, writing in 1923 that: "We shall be the leaders of the Orient against the Occident! I shall now have to alter my picture 'Peoples of Europe'. We belong on the other side! Once we have proved to the Germans that the French and English are not Whites at all but Blacks".[21] He declared Germany as "face of the East against the West" instead of being in the west, and wished for the destruction of the western countries like Britain, France, and America, declaring the French to be "negroids", and stating his disgust at the racial equality Britain was allowing for blacks.[22]

South Africa

Around 63,000 Chinese labourers were brought to South Africa between 1904 and 1910 to work the country's gold mines. Many were repatriated after 1910,[23][24] because of strong White opposition to their presence, similar to anti-Asian sentiments in the western United States during the same period. The mass importation of Chinese labourers to work on the gold mines contributed to the fall from power of the Conservative government in the United Kingdom, which was at the time responsible for governing South Africa after the Anglo-Boer War. However it did contribute to the economic recovery of South Africa after the Anglo-Boer War by once again making the mines of the Witwatersrand the most productive gold mines in the world.[25]: 103

On the 26 March 1904 a demonstration against Chinese immigration to South Africa was held in Hyde Park and was attended by 80,000 people.[25]: 107 The Parliamentary Committee of the Trade Union Congress then passed a resolution declaring that:

That this meeting consisting of all classes of citizens of London, emphatically protests against the action of the Government in granting permission to import into South Africa indentured Chinese labour under conditions of slavery, and calls upon them to protect this new colony from the greed of capitalists and the Empire from degradation.

— [26]

United Kingdom

In the 18th century, the Chinese were largely favorably viewed in Britain, being seen as a civilized, sophisticated people worthy of admiration and respect, but over the course of 19th century, British views of the Chinese grew increasingly hostile, with the Chinese being portrayed as inherently depraved and corrupt.[27] The phrase Yellow Peril was first used by a British newspaper on 21 July 1900 when the Daily News spoke of the “the yellow peril in its most serious form”.[27] At the same time, widespread Sinophobia in Britain did not translate into dislike of all Asians. During the Russian-Japanese War, France and Germany supported Russia while Britain supported Japan. British military observers to the war displayed a marked pro-Japanese bias against their traditional enemy Russia.[28] One British observer, Captain Pakenham's "...reporting tended to depict Russia as his enemy, not just Japan's".[29]

The British historian Julia Lovell wrote in 2014:

"In the early decades of the 20th century, Britain buzzed with Sinophobia. Respectable middle-class magazines, tabloids and comics alike spread stories of ruthless Chinese ambitions to destroy the west. The Chinese master-criminal (with his “crafty yellow face twisted by a thin-lipped grin”, dreaming of world domination) had become a staple of children’s publications. In 1911, “The Chinese in England: A Growing National Problem” (an article distributed around the Home Office) warned of “a vast and convulsive Armageddon to determine who is to be the master of the world, the white or yellow man”. After the First World War, cinemas, theatres, novels and newspapers broadcast visions of the “Yellow Peril” machinating to corrupt white society. In March 1929, the chargé d’affaires at London’s Chinese legation complained that no fewer than five plays showing in the West End depicted Chinese people in “a vicious and objectionable form”".[30]

British newspapers routinely warned their readers of the dangers of miscegenation, using the example of British women marrying Chinese men as proof of the racial threat posed by China to Britain, or more commonly warning that Triad gangsters were kidnapping British women into White slavery.[31] When World War One began, in 1914 the Defense of the Realm act was amended to include opium smoking as a grounds for deportation in order to provide a reason to start expelling people from London’s Chinatown.[31]

United States of America

In the USA, xenophobic fears against the alleged "Yellow Peril" led to the implementation of the Page Act of 1875, the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, expanded ten years later by the Geary Act. The Chinese Exclusion Act replaced the Burlingame Treaty ratified in 1868, which encouraged Chinese immigration, provided that "citizens of the United States in China of every religious persuasion and Chinese subjects in the United States shall enjoy entire liberty of conscience and shall be exempt from all disability or persecution on account of their religious faith or worship in either country" and granted certain privileges to citizens of either country residing in the other, withholding, however, the right of naturalization.

The Los Angeles pogrom of 1871 marked the beginning of widespread violence against the Chinese in the American West. It is estimated that in the 1870s-1880s that about 200 Chinese were lynched in the American West.[32] In 1880, a pogrom in Denver saw the looting and destruction of the local Chinatown, which was burned down with one Chinese man lynched.[33] So common were the practice of lynching Chinese in the West that phrase Not having a Chinaman's chance arose to mean no chance at all. On 2 September 1885 there occurred the Rock Springs massacre in Wyoming, yet another anti-Chinese pogrom committed by white miners who saw the Chinese miners as rivals which led to 28 deaths (all Chinese), 15 wounded, the expulsion of rest of the Chinese community, and property damage worth $150,000.[34] The Rock Springs pogrom led to a wave of anti-Chinese violence in the West in the fall of 1885-winter 1886. On 11 September 1885, there was an anti-Chinese pogrom in Coal Creek.[35] Also on 11 September there was an anti-Chinese attack in Squak Valley that left 3 Chinese workers dead. On 24 October 1885, the Chinatown of Seattle was party burned down and 3 November 1885 the Tacoma pogrom saw the entire Chinese community expelled.[36] On 6-9 February 1886, there occurred the Seattle pogrom that led to 200 Chinese being expelled due to an attack organized by the local Knights of Labor chapter. In 1887, between 10-34 Chinese were killed at the Chinese Massacre Cove in Oregon.

The Immigration Act of 1917 then created an "Asian Barred Zone" under nativist influence. The Cable Act of 1922 guaranteed independent female citizenship only to women who were married to "alien[s] eligible to naturalization".[37] At the time of the law's passage, Asian aliens were not considered to be racially eligible for U.S. citizenship.[38][39] As such, the Cable Act only partially reversed previous policies, granting independent female citizenship only to women who married non-Asians. The Cable Act effectively revoked the U.S. citizenship of any woman who married an Asian alien. The National Origins Quota of 1924 also included a reference aimed against Japanese citizens, who were ineligible for naturalization and could not either be accepted on U.S. territory. In 1922, a Japanese citizen attempted to demonstrate that the Japanese were members of the "white race", and, as such, eligible for naturalization. This was denied by the Supreme Court in Takao Ozawa v. United States, who judged that Japanese were not members of the "Caucasian race".

The 1921 Emergency Quota Act, and then the Immigration Act of 1924, restricted immigration according to national origins. While the Emergency Quota Act used the census of 1910, xenophobic fears in the WASP community lead to the adoption of the 1890 census, more favorable to White Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP) population, for the uses of the Immigration Act of 1924, which responded to rising immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe, as well as Asia.

One of the goal of this National Origins Formula, established in 1929, was explicitly to keep the status quo distribution of ethnicity, by allocating quotas in proportion to the actual population. The idea was that immigration would not be allowed to change the "national character". Total annual immigration was capped at 150,000. Asians were excluded but residents of nations in the Americas were not restricted, thus making official the racial discrimination in immigration laws. This system was repealed with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

The phrase "yellow peril" was common in the U.S. newspapers owned by William Randolph Hearst.[40] It was also the title of a popular book by an influential U.S. religious figure, G. G. Rupert, who published The Yellow Peril; or, Orient vs. Occident in 1911. Based on the phrase "the kings from the East" in the Christian scriptural verse Revelation 16:12,[41] Rupert, who believed in the doctrine of British Israelism, claimed that China, India, Japan, and Korea were attacking England and the United States, but that Jesus Christ would stop them.[42] Rupert believed that all the "colored races" would eventually unite under the leadership of Russia, producing a final apocalyptic confrontation.

According to the American science fiction writer William F. Wu, "pulp magazines in the 1930s had a lot of yellow peril characters loosely based on Fu Manchu" and that although "most were of Chinese descent", the geopolitics at the time led a "growing number of people to see Japan as a threat" as well. In his 1982 book The Yellow Peril: Chinese Americans in American fiction, 1850-1940, Wu theorizes that the fear of Asians dates back to Mongol invasion in the Middle Ages during the Mongol Empire. "The Europeans believed that Mongols were invading en masse, but actually, they were just on horseback and riding really fast," he writes. Most Europeans had never seen an Asian before, and the harsh contrast in language and physical appearance probably caused more skepticism than transcontinental immigrants did. "I think the way they looked had a lot to do with the paranoia," Wu says.[43]

New Zealand

The "yellow peril" was a significant part of the policy platform promoted by Richard Seddon, a populist New Zealand prime minister, in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century. He compared Chinese people to monkeys. In his first political speech in 1879 he had declared New Zealand did not wish her shores to be "deluged with Asiatic Tartars. I would sooner address white men than these Chinese. You can't talk to them, you can't reason with them. All you can get from them is 'No savvy'."[44] In 1905, Lionel Terry, a fanatical white supremacist murdered an elderly Chinese immigrant Joe Kum Yung, in Wellington to protest Asian immigration to New Zealand.

Measures designed to curb Chinese immigration included a substantial poll tax following Imperial Japan's invasion and occupation of China, which was abolished in 1944 and for which the New Zealand government has since issued a formal apology.

France

Starting in the 1890s, the péril jaune (yellow peril) was often invoked in France, with unfavorable comparisons between drawn between low French birth rates and high Asian birth rates.[45] According, the fear was raised that eventually the Asians would "flood" France, and that the only way to prevent the Asian "flooding" of France was to raise the French birth rate to have enough manpower to fight off the coming Asian "flood".[46] During the Russian-Japanese war of 1904-05, the French media was overwhelming on the side of France's ally Russia.[47] The Russians were portrayed in the French press as heroically fighting for the entire "white race" against the péril jaune of the Japanese "barbarians".[48] During the Indochina war of 1945-54, the French often justified the war as part of the struggle to defend the West against the péril jaune of the Vietnamese Communists, who were always portrayed as mere puppets of the Chinese Communists in their drive to conquer the world.[49] According to the French writer Gisèle Luce Bousquet in 1991, the concept of the péril jaune, which had traditionally colored French attitudes towards Asians, especially the Vietnamese is still in effect, albeit in more subtle ways than in the past.[50] Franco-Vietnamese were resented for being perceived academic over-achievers who were taking away good-paying jobs from the "native French", and for allegedly "taking over" entire fields such as computer science.[51]

Mexico

During the Mexican Revolution, the Chinese communities in Mexico who usually working there as miners who all subjected to abuse from various factions in the revolution.[52] The most notable act of anti-Chinese violence was the Torreón massacre of May 11-15 1911 when over 300 Chinese were shot down in cold blood by rebel forces commanded by General Pancho Villa. The Torreón massacre was the most extreme act of anti-Asian violence in Mexico, but not the only one. In 1913, when Tamosopo was taken by the Constitutional Army, all of the buildings owned by Chinese immigrants were sacked and burned down.[53] The British historian Alan Knight noted that all sides tended to single out the Chinese for "especially harsh treatment".[54] During and after the revolution, Chinese Mexicans were widely disliked because of their supposed tendency to steal jobs from Mexicans.In the 1930s, when nearly 70% of the country Chinese and Chinese-Mexican population was deported or otherwise expelled out of the country.[55]

Eastern Front

After Germany launched Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, German propaganda almost always referred to the Red Army as the "Asiatic horde", with the Red Army being portrayed as a vast horde of barely human Asian savages capable of only the most mindless destruction, who were intent on destroying European civilization.[56] Barbarossa was always portrayed in German propaganda as a "preventive war" allegedly forced on Germany by a Soviet invasion said to be planned for July 1941, and which thus justified German war crimes in the Soviet Union as something forced on Germany. The German historian Wolfram Wette wrote that it was the great achievement of anti-Soviet Nazi propaganda to mix anti-Slavic, anti-Asian and anti-Semitic images into a potent cocktail of hate, which portrayed the "Asiatic" Soviet Union supposedly ruled by the Jews as the embodiment of everything evil in the world.[57] German propaganda always portrayed the Red Army after the start of Barbarossa as a vast horde of Slavic and Asian Untermensch ("sub-humans") commanded by evil Jewish commissars, who were all set to attack Germany and destroy the West.[58] Typical of such viewpoint was the following passage from the pamphlet "Information for the troops", which all 3 million German soldiers committed to Barbarossa had to read in June 1941:

"Anyone who has ever looked into the face of a Red commissar knows what the Bolsheviks are. There is no need here for theoretical reflections. It would be an insult to animals if one were to call the features of these, largely Jewish, tormentors of people beasts. They are the embodiment of the infernal, of the personified insane hatred of everything that is noble in humanity. In the shape of these commissars we witness the revolt of the subhuman against noble blood. The masses whom they are driving to their deaths with every means of icy terror and lunatic incitement would have brought about an end of all meaningful life, had the incursion not been prevented at the last moment" [the last statement is a reference to the "preventive war" that Barbarossa was alleged to be].[58]

Such talk were not just propaganda for the masses, but rather that was genuinely believed by German elites. During the planning for Barbarossa, the German General Staff took it for granted that the Soviet Union was a primitive, backward "Asiatic" power that it would take Germany only two to three months to defeat, which accordingly meant that Germany could wage a "war of annihilation" against the Soviet Union, secure in the knowledge that they had no need to fear Soviet revenge.[59] Typical of the German anti-Soviet propaganda was the following message to his troops issued by General Erich Hoepner just before Barbarossa:

"The war against Russia is an important chapter in the German nation's struggle for existence. It is the old battle of the Germanic against the Slavic people, of the defense of European culture against Muscovite-Asiatic inundation and of the repulse of Jewish Bolshevism. The objective of this battle must be the demolition of present-day Russia and must therefore be conducted with unprecedented severity. Every military action must be guided in planning and execution by an iron resolution to exterminate the enemy remorselessy and totally. In particular no adherents of the contemporary Russian Bolshevik system are to be spared".[60]

The British historian Richard J. Evans wrote that Wehrmacht officers regarded the Russians as "sub-human", were from the time of the invasion of Poland in 1939 telling their troops the war was caused by "Jewish vermin", and explained to the troops that the war against the Soviet Union was a war to wipe out what were variously called "Jewish Bolshevik sub-humans", the "Mongol hordes", the "Asiatic flood" and the "red beast", language clearly intended to produce war crimes by reducing the enemy to something less than human.[61] During the first six months of Operation Barbarossa, the Wehrmacht and the SS had a policy of shooting all of the "Asiatics" serving in the Red Army who were taken prisoner by German forces.[62] Thousands of Soviet POWs were thus executed for no other reason then for being Asian.[62] After December 1941, the Germans ceased executing Soviet Asian POWs as their labor was now needed once it was clear that the war against the Soviet Union was going to be a long war. Some of the Asian Red Army POWs either volunteered or were conscripted into the Ostlegionen (Eastern Legions) of the Wehrmacht. The Asians serving in the Ostlegionen were generally known as "Mongols", regardless if they were actually Mongol or not.[63] The British travel writer Eric Newby described his guards at a German POW in Italy thus:

"They were Mongols, apostates from the Russian Army, dressed in German uniform, hideously cruel descendants of Genghis Khan's wild horsemen who, in Italy, had already established a similar reputation to that enjoyed by the Goums, the Moroccans in the Free French Army."[63]

It is estimated that in 1945 that Red Army soldiers raped two million German women and girls during their advance into Germany.[64] Russian sources acknowledge the mass rapes, but reflecting the prevalence of Yellow Peril stereotypes in Russia insist that most of the rapes were committed by Soviet Asian peoples serving in the second-line units, not by soldiers in the first-line units, who were usually ethnic Russians.[63]

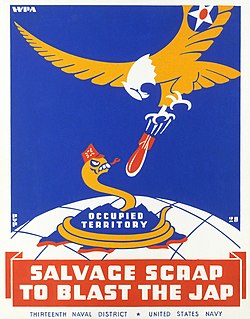

Pacific War

The most profound cause of anti-Japanese sentiment outside of Asia had its beginning in the attack on Pearl Harbor. The Japanese attack propelled the United States into World War II. The Americans were unified by the attack to fight against the Empire of Japan and its allies, Nazi Germany and fascist Italy.

The unannounced attack at Pearl Harbor prior to a declaration of war was presented to the American populace as an act of treachery and cowardice. Following the attack many non-governmental "Jap hunting licenses" were circulated around the country. LIFE magazine published an article on how to tell a Japanese from a Chinese person by the shape of the nose and the stature of the body.[65] Japanese conduct during the war did little to quell anti-Japanese sentiment. Fanning the flames of outrage were the treatment of American and other prisoners of war. Military-related outrages included the murder of POWs, the use of POWs as slave labor for Japanese industries, the Bataan Death March, the Kamikaze attacks on Allied ships, and atrocities committed on Wake Island and elsewhere.

U. S. historian James J. Weingartner attributes the very low number of Japanese in U.S. POW compounds to two key factors: a Japanese reluctance to surrender and a widespread American "conviction that the Japanese were 'animals' or 'subhuman' and unworthy of the normal treatment accorded to POWs."[66] The latter reasoning is supported by Niall Ferguson, who says that "Allied troops often saw the Japanese in the same way that Germans regarded Russians [sic] — as Untermenschen."[67] Weingartner believes this explains the fact that a mere 604 Japanese captives were alive in Allied POW camps by October 1944.[68] Ulrich Straus, a U.S. Japanologist, believes that front line troops intensely hated Japanese military personnel and were "not easily persuaded" to take or protect prisoners, as they believed that Allied personnel who surrendered, got "no mercy" from the Japanese.[69] Allied soldiers believed that Japanese soldiers were inclined to feign surrender, in order to make surprise attacks.[69] Therefore, according to Straus, "[s]enior officers opposed the taking of prisoners[,] on the grounds that it needlessly exposed American troops to risks ..."[69]

An estimated 112,000 to 120,000 Japanese migrants and Japanese Americans from the West Coast were interned regardless of their attitude to the US or Japan. They were held for the duration of the war in the inner US. The large Japanese population of Hawaii was not massively relocated in spite of their proximity to vital military areas.

A 1944 opinion poll found that 13% of the U.S. public were in favor of the extermination of all Japanese.[70][71] Daniel Goldhagen wrote in his book "So it is no surprise that Americans perpetrated and supported mass slaughters - Tokyo's firebombing and then nuclear incinerations - in the name of saving American lives, and of giving the Japanese what they richly deserved."[72]

Korean War

During the Korean War, the vast majority of the various contingents serving under the United Nations flag loathed Korea and Koreans, who were viewed as a loathsome people living in a loathsome country.[73] A notable exception were the British troops, who tended to despise adult Koreans as "gooks", but were well known for their kindness towards Korean children.[74] When the Chinese entered the war in November 1950, and drove the United Nations (of which the largest contingent was American) back down the Korean peninsula during the winter of 1950-51, American commanders routinely explain away their defeats by claiming that were faced with vast "hordes" of drug-crazed Chinese who overwhelming them via sheer numbers in supposed vast "human wave" assaults.[75] The British military historian Colonel Michael Hickey noted: "In fact, the Chinese seldom attacked at more than regimental strength. They placed far more stress on fieldcraft, deception and surprise than on weight on numbers".[76] One sarcastic American reporter, noting the tendency of American officers to exaggerate Chinese numbers, asked "How many hordes are there in a platoon?".[77]

The Historikerstreit

Yellow Peril stereotypes were often invoked during the Historikerstreit (Historians' Dispute) in West Germany of 1986-89. The German historian Ernst Nolte sparked much controversy with his thesis that the Holocaust was something that Hitler had forced to do because of fear of the Soviet Union. Nolte wrote about the horrors said to been perpetuated by the "Chinese Cheka" during the Russian Civil War, and made much about the supposed use of Chinese serving in the Cheka of the rat cage torture, which was alleged to be an ancient Chinese torture.[78][79] Nolte used the "rat cage torture" to establish the "Asiatic barbarism" of the Bolsheviks.[80] The crux of Nolte's thesis was presented when he wrote:

"It is a notable shortcoming of the literature about National Socialism that it does not know or does not want to admit to what degree all the deeds—with the sole exception of the technical process of gassing—that the National Socialists later committed had already been described in a voluminous literature of the early 1920s: mass deportations and shootings, torture, death camps, extermination of entire groups using strictly objective selection criteria, and public demands for the annihilation of millions of guiltless people who were thought to be "enemies".

It is probable that many of these reports were exaggerated. It is certain that the “White Terror” also committed terrible deeds, even though its program contained no analogy to the “extermination of the bourgeoisie”. Nonetheless, the following question must seem permissible, even unavoidable: Did the National Socialists or Hitler perhaps commit an “Asiatic” deed merely because they and their ilk considered themselves to be the potential victims of an “Asiatic” deed? Wasn’t the 'Gulag Archipelago' more original than Auschwitz? Was the Bolshevik murder of an entire class not the logical and factual prius of the "racial murder" of National Socialism? Cannot Hitler's most secret deeds be explained by the fact that he had not forgotten the rat cage? Did Auschwitz in its root causes not originate in a past that would not pass?"[81]

Along the same lines, Nolte had taken to referring to the Red Army as the "Asiatic horde".[82] At the same time, another German historian Andreas Hillgruber argued that final stand of the Wehrmacht was a "justified" act that all historians should "identify" with as the Wehrmacht was the only thing that prevented the "flooding" of Central Europe by the Red Army.[83][84] The American historian Kriss Ravetto noted that Hillgruber's picture of the Red Army as the "Asiatic hordes" who personified sexual barbarism and his use of "flooding" and body penetration imagery seemed to invoke traditional Yellow Peril stereotypes, as well perhaps of deep-settled personal anxieties of his own.[85] The German historian Hans Mommsen wrote in his opinion that Nolte's use of the phrase "Asiatic hordes" to describe Red Army soldiers, and his use of the word "Asia" as a byword for all that is horrible and cruel in the world reflected anti-Asian racism.[82] Evans wrote about Nolte's tendency to use the word Asiatic to describe Soviet crimes:

"The use of the word "Asiatic", even with the limited distance lent it by its enclosure in quotation marks, to describe the misdeeds of the Bolsheviks, inevitably recalls years of racist scaremongering, in which Communism was portrayed as the creed of slit-eyed subhumans threatening Germany from the East".[86]

Nolte's thesis that Hitler was forced into committing the Holocaust is not widely accepted, and his reputation today as a historian is that of a "marginalized" figure.[87]

Fiction

- In 1898, the British writer M. P. Shiel published a short story serial entitled The Empress of the Earth. The later novel edition was named The Yellow Danger. Shiel's novel centers on the murder of two German missionaries in Kiau-Tschou in 1897 and features the Chinese villain, Dr. Yen How.

- Emile Driant, a French officer and political activist, wrote under the pen name of Capitaine Danrit The Yellow Invasion in 1905. The story depicts the surprise attack against the Western world by a gigantic Sino-Japanese army, covertly equipped with American-made weapons and secretly trained in the remote Chinese hinterland. The plot is hatched by a Japanese veteran of the Russo-Japanese War: coming out of the war with a fanatical hatred of Westerners, he organizes a world-spanning secret society named the Devouring Dragon in order to destroy Western civilization.

- Jack London's 1914 story "The Unparalleled Invasion", presented as a historical essay narrating events between 1976 and 1987, describes a China with an ever-increasing population taking over and colonising its neighbors, with the intention of eventually taking over the entire Earth. Thereupon the nations of the West open biological warfare and bombard China with dozens of the most infectious diseases—among them smallpox, yellow fever, cholera, and Black Death—with all Chinese attempting to flee being shot down by armies and navies massed around their country's land and sea borders, and the few survivors of the plague invariably put to death by expeditions entering China. This genocide is described in considerable detail, and nowhere is there mentioned any objection to it. The terms "yellow life" and "yellow populace" appear in the story. It ends with "the sanitation of China" and its re-settlement by Westerners, "the democratic American programme" as London puts it.[89]

- The J. Allan Dunn novel, The Peril of the Pacific, a 1916 serial in the pulp magazine People's, describes an attempted invasion of the western United States by Japan. The novel, set in 1920, posits an alliance between Japanese immigrants in America and the Japanese navy. It reflects contemporaneous anxiety over the status of Japanese immigrants, 90% of whom lived in California, and who were exempt from anti-immigration legislation in accordance with the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907. The novel implies that the primary loyalty of America's Japanese immigrants was to their homeland.[90]

- Philip Francis Nowlan's novella Armageddon 2419 A.D., which first appeared in the August 1928 and was the start of the long-lasting popular Buck Rogers series, depicted a future America which had been occupied and colonized by cruel invaders from China, which the hero and his friends proceed to fight and kill wholesale.

- Pulp author Arthur J. Burks contributed a series of eleven short stories to All Detective Magazine (1933–34) featuring detective Dorus Noel in conflict with a variety of sinister operators in Manhattan's Chinatown.

- Robert A. Heinlein's novel Sixth Column depicts American resistance to an invasion by a blatantly racist and genocidally cruel "PanAsian" empire.

- H. P. Lovecraft was in constant fear of Asiatic culture engulfing the world[91] and a few of his stories reflect this, such as The Horror At Red Hook, where "slant-eyed immigrants practice nameless rites in honor of heathen gods by the light of the moon", and He, where the protagonist is given a glimpse of the future—the "yellow men" have conquered the world, and now dance to their drums over the ruins of the white man.

- Yellow Peril is a book by Wang Lixiong, written under the pseudonym Bao Mi, about a civil war in the People's Republic of China that becomes a nuclear exchange and soon engulfs the world, causing World War III. It's notable for Wang Lixiong's politics, as a Chinese dissident and outspoken activist; its publication following the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989; and its popularity due to bootleg distribution across China even when the book was banned by the Communist Party of China.[92]

- In A Separate Peace by John Knowles, Phineas and Gene decide that Brinker is Madame Chiang Kai-shek, and is therefore Chinese. They nickname him Yellow Peril.

- "Yellow Peril" is also the name of a song written and performed by Steely Dan founders Donald Fagen and Walter Becker before the first Steely Dan album, later released on various anthologies such as Becker and Fagen: The Early Years. The song includes various Asian motifs and references predating later Steely Dan and related works such as "Bodhisattva", "Aja", and "Green Flower Street".

- In a 2007 graphic pornographic horror short story “The Fall: With A Whimper” by a Canadian horror writer published under the pseudonym Tantric Legion, intelligent parasitical worms arrive in China from outer space, which are described as “sexual parasites” in the story.[93] The phallic-shaped worms in quasi-rape scenes penetrate into human bodies by forcing their way into vaginas and anuses, and then take over the minds of their victims.[93] The story concerns a pretty young schoolteacher in Jiuquan named Mei, who spends the first half of the story attempting to avoid being infected, and after she herself is infected, sets out to infect the rest of humanity.[94] Once infected, “Mei host” as she now calls herself considers herself to be a "good slave" whose only longings is to do the bidding of her “masters” as she calls the worms that control her mind and body, and her only desire is to create a “glorious new civilization”, where all humanity will be blessed by a “shared consciousness”.[94] The worms also transform the bodies of their victims, and Mei now endowed with “swollen breasts and a constant state of sexual arousal”, has no trouble seducing people, who she then infects.[94] At the climax of the story, Mei seduces and infects the leader of China.[95] Having sex with Party Secretary Chen, Mei orgasms and as she does, she releases some of the worms within her body, which crawl out of her vagina, and while the hapless Chen is held in place by Mei, the worms proceed to force their way into his body via his rectum.[93] Once in control in China, millions of infected Chinese are send out to infect the rest of humanity. The story ends with thousands of infected Chinese, all eerily silent and controlled by an inhuman collective intelligence, boarding planes at airports all over China to achieve the goal of subjecting humanity.[93] The infected Chinese are compared to insects, whose attacks on other countries are described as a "swarming".[93] The story invokes much of the imagery associated with the Yellow Peril theory, albeit in a much more sexualized and literalized way than traditionally was the case. The Yellow Peril theory often invoked images of flooding, invasion, swarming and body penetration, and of vast, mindless insect-like Asian masses controlled by a sinister intelligence.[96] The story not only invokes the flood and bodily penetration imagery associated with the Yellow Peril theory, but also the classic Yellow Peril stereotype of the Chinese as a vast, inhuman horde with no real individual personalities overwhelming the rest of humanity.

Fu Manchu and kin

The Yellow Peril was a common theme in the fiction of the time. Perhaps most representative of this is Sax Rohmer's Fu Manchu novels. Dr. Fu Manchu is an evil Chinese mad scientist/gangster out to take over the world, and being constantly foiled by the British policeman/spy Sir Denis Nayland Smith, and his assistant Dr. Petrie. The Fu Manchu character is believed to have been patterned on the antagonist of the 1898 Yellow Peril series by British writer M. P. Shiel. About the character of Dr. Fu Manchu, the British writer Jack Adrian wrote that Rohmer was :

"...a shameless inflater of a peril that was no peril at all (the "Yellow Peril") into an absurd global conspiracy.

He had not even the excuse (if excuse is the word) of his predecessor in this shabby lie, M.P. Shiel, who was a vigorous racist, sometimes exhibiting a hatred and horror of Jews and Far Eastern races. Rohmer's own racism was careless and casual, a mere symptom of the times. But he recognized other's people's fears and loathings, and tapped directly into them with his saga of the fiendish, and seemingly deathless, Dr. Fu Manchu, whose millions of minions were ever bidding their time, awaiting the order to inundate and subjugate the Western white races, and particularly the British Isles. Even more particularly, London, for at the heart of the Empire the teeming hordes of "heathen Chinese" swarmed like hyperactive rats around Limehouse Reach and Wapping Old Stairs, poised to flood the capital, turn its citizens into opium or cocaine addicts, and carry off the flower of British maidenhood to the stews of Shanghai.

This nonsense was believed more or less seriously by just about all classes, even though, as the sociologist Virginia Berridge has determined, the ethnic Chinese population of the Limehouse area-indeed, the whole of London's East End-in the period 1900 through to the Second World War ran to a few hundred at most, the majority of whom were engaged in respectable professions such as cooking and laundering (clothes, not money). As for narcotics, this was notably the province of "black" immigrants than "yellow" (the well-heeded Chinese restaurant-owner "Brilliant Chang" notwithstanding), most of the actual drugs coming from Germany, where cocaine production was virtually unregulated. And so far as white slavery went, it was to Buenos Aires that most of the young girls (dancers, usually lured by spurious advertisements in The Stage) traveled.

Nevertheless, with Fu Manchu and his strange cohorts and even more bizarre "pets" (monstrous spiders, lizards, hamadryads, batrachians unknown to science, murderous lepidopterae, Venus fly-traps capable of digesting a man) Rohmer accomplished what all writers of popular fiction yearn for but rarely achieve-the creation of a character who transcends mere popularity and becomes an entry in the dictionary."[97]

Film adaptations of the Dr. Fu Manchu novels are typified by The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932), with Boris Karloff playing the title role. The Irish film studies professor Rod Stoneman noted how "...Rohmer’s concoction of cunning Asian villainy connects with the irrational fears of proliferation and incursion: racist myths often carried by the water imagery of flood, deluge, the tidal waves of immigrants, rivers of blood."[96] Through Rohmer always denied being a racist, in 1936 when his novels were banned in Germany (the Nazi regime thought the name Rohmer sounded Jewish), Rohmer wrote a letter where he declared he was “a good Irishman” and he did not know why his novels had been banned because “my stories are not inimical to Nazi ideals”.[96]

Another is Li Shoon, a fictional villain of Chinese ethnicity created by H. Irving Hancock, first published in 1916. As common in the pulp fiction of the times, the depiction of Li Shoon had considerable racial stereotypes. He was described as being "tall and stout" and having "a round, moonlike yellow face" topped by "bulging eyebrows" and "sunken eyes". He has "an amazing compound of evil" which makes him "a wonder at everything wicked", and "a marvel of satanic cunning". DC Comics featured "Ching Lung" in Detective Comics, and he appeared on the cover of the first issue (March 1937).

Emperor Ming the Merciless, nemesis of Flash Gordon, was another iteration of the Fu Manchu trope. Peter Feng calls him a "futuristic Yellow Peril", quoting a reviewer who referred to Ming as a "slanty eyed, shiny doomed, pointy nailed, arching eyebrowed, exotically dressed Oriental".[98] Likewise, Buck Rogers fought against the "Mongol Reds" also known as "Hans", who had taken over America in the 25th century.

In the late 1950s, Atlas Comics (now Marvel Comics) debuted the Yellow Claw, a Fu Manchu pastiche. Marvel would later use the actual Fu Manchu as the principal foe of his son, Shang-Chi, Master of Kung Fu in the 1970s. Other characters inspired by Rohmer's Fu Manchu include Pao Tcheou.

A 1977 Doctor Who serial, The Talons of Weng-Chiang, builds a science fiction plot upon another loose Fu Manchu pastiche. In this case, the key "yellow devil" character serves to enable an ill-intentioned time traveller from the fifty-first century. The principle villain is not Chinese, but rather a deformed Caucasian man named Magnus Greel, a war criminal from 51st century who has escaped into the 19th century, and is posing as the (fictional) Chinese god Weng-Chiang. Greel's followers are the Tong of the Black Scorpion, who are willing to obey his every command. Besides for the murderous Peking Homunculus cyborg, Greel's principle assistant is the magician Li H'sen Chang, the supposed leader of the Black Scorpion triad, who kidnaps British women to be dissolved in order to provide Greel with their "life essences" to keep him alive. Greel is not Asian, but the fact that the Chinese characters worship Greel as the god Weng-Chiang whereas the British characters can clearly realize that Greel is no god seems to be suggesting that Chinese have lower intelligence than the British.

Yellow Peril: The Adventures of Sir John Weymouth-Smythe, by Richard Jaccoma (1978) is both a pastiche and a benign parody of the Sax Rohmer novels.[99] As the title suggests, it's a distillation of the trope, focusing on the psychosexual stereotype of the seductive Asian woman as well that of the ruthless Mongol conqueror that underlies much of supposed threat to Western civilization. Written for a sophisticated modern audience, it uses the traditional use of first-person narrative to portray the nominal hero Sir John Weymouth-Smythe as simultaneously a lecher and a prude, torn between his desires and Victorian sensibilities but unable to acknowledge, much less resolve, his conflicted impulses. Set in the 1930s, the novel concerns the quest for the mystical "Spear of Destiny", which gives whoever possesses it control of the world. Weymouth-Smythe spends much of the novel battling a Dr. Fu Manchu-type character named Chou en Shu for the Spear of Destiny, only for it to be revealed Chou is not the villain at all. Rather the real danger were the German characters who were all fanatical Nazis and who were Weymouth-Smythe's nominal allies in seeking the Spear of Destiny. Chou en Shu is an ancient Chinese mystic with an enormous penis who rapes women (who greatly enjoy the experience), and turns them into his devoted, willing slaves (there is something within his semen that takes over the minds of his female victims), using them as his tools to accomplish his goals. Chou's mission is to foil the Nazis in their efforts to take control of the Spear of Destiny, in order to save the world. The fact that Weymouth-Smyte does not realize until it almost too late that the Nazis are the real danger rather the "Yellow Peril" stereotype he rather mindlessly associates with Chou is novel's way of saying that it is fascism and racism within the West, not an imagery "Yellow Peril" that the real danger to the world. The cover blurbs for the paperback edition declaim "Erotic adventure in the style of the original 'pulps'" and "'A Porno-Fairytale-Occult-Thriller!' according to the Village Voice". It is clearly in the same line as the contemporaneous works of Philip José Farmer, "updating" Rohmer the way Farmer updated Edgar Rice Burroughs, Lester Dent, and Walter B. Gibson.

See also

- Alien land laws

- Asian American

- Anti-Mongolianism

- Chinese Massacre of 1871

- Chink

- Model minority

- Black face

- Murder of Vincent Chin

- Racism

- Red Chinese Battle Plan

- Sinophobia

- Stereotypes of East Asians in the Western world

- Turban Tide - Similar fears toward Indian immigrants

- White Australia policy

- Xenophobia

References

- ^ a b c d e Yang, Tim (February 19, 2004). "The Malleable Yet Undying Nature of the Yellow Peril". Dartmouth College. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ Leung, Wing Fai (16 August 2014). "Perceptions of the East – Yellow Peril: An Archive of Anti-Asian Fear". The Irish Times. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tsu, Jiang Failure, Nationalism, and Literature: The Making of Modern Chinese Identity, 1895-1937 Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005 page 80

- ^ G. G. Rupert, The Yellow Peril or, the Orient versus the Occident, Union Publishing, 1911, p. 9

- ^ Daniel C. Kane, introduction to A.B. de Guerville, Au Japon, Memoirs of a Foreign Correspondent in Japan, Korea, and China, 1892-1894 (West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press, 2009), p. xxix.

- ^ a b c Palmer, James The Bloody White Baron, New York: Basic Books, 2009 page 31.

- ^ a b Röhl, John The Kaiser and his Court: Wilhelm II and the Government of Germany, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996 page 203

- ^ Röhl, John The Kaiser and his Court: Wilhelm II and the Government of Germany, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996 pages 203-204

- ^ Palmer, James The Bloody White Baron, New York: Basic Books, 2009 pages 30-31.

- ^ Palmer, James The Bloody White Baron, New York: Basic Books, 2009 pages 31.

- ^ a b Palmer, James The Bloody White Baron, New York: Basic Books, 2009 pages 57-58.

- ^ Palmer, James The Bloody White Baron, New York: Basic Books, 2009 page 253.

- ^ Palmer, James The Bloody White Baron, New York: Basic Books, 2009 page 21.

- ^ Jukes, Geoffrey The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905, London: Osprey 2002 page 84.

- ^ Jukes, Geoffrey The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905, London: Osprey 2002 page 84.

- ^ a b Palmer, James The Bloody White Baron, New York: Basic Books, 2009 page 57.

- ^ Röhl, John The Kaiser and his Court: Wilhelm II and the Government of Germany, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996 page 14

- ^ C.E.W Bean; ANZAC to Amiens; Penguin Books; 2014 Edition; p.5

- ^ a b c Röhl, John The Kaiser and his Court: Wilhelm II and the Government of Germany, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996 page 204

- ^ Wette, Wolfram The Wehrmacht, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006 pages 12-13

- ^ John C. G. Röhl (1996). The Kaiser and his Court: Wilhelm II and the Government of Germany. Translated by Terence F. Cole (reprint, illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 0521565049. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ John C. G. Röhl (1996). The Kaiser and his Court: Wilhelm II and the Government of Germany. Translated by Terence F. Cole (reprint, illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 210. ISBN 0521565049. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "In South Africa, Chinese is the New Black". Wall Street Journal. June 19, 2008.

- ^ Park, Yoon Jung (2009). Recent Chinese Migrations to South Africa - New Intersections of Race, Class and Ethnicity (PDF). Interdisciplinary Perspectives. ISBN 978-1-904710-81-3. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Yap, Melanie; Leong Man, Dainne (1996). Colour, Confusion and Concessions: The History of the Chinese in South Africa. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. p. 510. ISBN 962-209-423-6.

- ^ Official programme of the great demonstration in Hyde Park, [S.l.:s.n.]; Richardson (1904). Chinese mine labour in the Transvaal. London: Parliamentary Committee of the Trade Union Congress. pp. 5–6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b French, Philip (20 October 2014). "The Yellow Peril: Dr Fu Manchu & the Rise of Chinaphobia". The Observer. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Jukes, Geoffrey The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905, London: Osprey, 2002 page 91.

- ^ Jukes, Geoffrey The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905, London: Osprey, 2002 page 91.

- ^ Lowell, Julia (30 October 2014). "The Yellow Peril: Dr Fu Manchu & the Rise of Chinaphobia". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ a b Witchard, Anne (13 November 2014). "Writing China: Anne Witchard on 'England's Yellow Peril'". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Infamous Lynchings". 20 October 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Infamous Lynchings". 20 October 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "The Anti-Chinese Hysteria of 1885-1886". The Chinese-American Experience 1857-1892. Harpweek. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "The Anti-Chinese Hysteria of 1885-1886". The Chinese-American Experience 1857-1892. Harpweek. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "The Anti-Chinese Hysteria of 1885-1886". Harpweek. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Prologue: Selected Articles". Archives.gov. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ "For Teacher - An Introduction to Asian American History". Apa.si.edu. 19 February 1942. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Foreign News: Again, Yellow Peril". Time. 1933-09-11.

- ^ "Revelation 16:12 (New King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ^ "NYU's "Archivist of the Yellow Peril" Exhibit". Boas Blog. 2006-08-19. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ^ Contact Lisa Katayama: Comment (29 August 2008). "The Yellow Peril, Fu Manchu, and the Ethnic Future". Io9.com. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ Randal Mathews Burdon, King Dick: A Biography of Richard John Seddon, Whitcombe & Tombs, 1955, p.43.

- ^ Cook Anderson, Margaret Regeneration through Empire: French Pronatalists and Colonial Settlement in the Third Republic, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014 page 25

- ^ Cook Anderson, Margaret Regeneration through Empire: French Pronatalists and Colonial Settlement in the Third Republic, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014 page 25

- ^ Beillevaire, Patrick x, "L'opinion publique française face à la guerre russo-japonaise" from Cipango, cahiers d'études japonaises , Volume, 9, Autumn 2000, pages 185-232.

- ^ Beillevaire, Patrick x, "L'opinion publique française face à la guerre russo-japonaise" from Cipango, cahiers d'études japonaises , Volume, 9, Autumn 2000, pages 185-232.

- ^ Shafer, Michael Deadly Paradigms: The Failure of U.S. Counterinsurgency Policy Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014 page 145

- ^ Bousquet, Gisèle Luce Behind the Bamboo Hedge: The Impact of Homeland Politics in the Parisian Vietnamese Community, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1991 page 75

- ^ Bousquet, Gisèle Luce Behind the Bamboo Hedge: The Impact of Homeland Politics in the Parisian Vietnamese Community, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1991 page 75

- ^ Knight, Alan The Mexican Revolution Volume 2 Counter-revolution and reconstruction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987 page 44.

- ^ Knight, Alan The Mexican Revolution Volume 2 Counter-revolution and reconstruction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987 page 44.

- ^ Knight, Alan The Mexican Revolution Volume 2 Counter-revolution and reconstruction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987 page 279.

- ^ Campos Rico, Ivonne Virginia (2003). La Formación de la Comunidad China en México: políticas, migración, antichinismo y relaciones socioculturales (thesis) (in Spanish). Mexico City: Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH-SEP). p. 108.

- ^ Merridale, Catherine Ivan's War: The Red Army at War 1939-45, London: Faber & Faber, 2011 pages xxxviii, 449 & 466.

- ^ Wette, Wolfram The Wehrmacht, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006 page 16

- ^ a b Förster, Jürgen "The German Military's Image of Russia" pages 117–129 from Russia War, Peace and Diplomacy edited by Ljubica Erickson & Mark Erickson, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004 page 127.

- ^ Wette, Wolfram The Wehrmacht, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006 pages 21-22

- ^ Förster, Jürgen "The Wehrmacht and the War of Extermination Against the Soviet Union" pages 494-520 from The Nazi Holocaust Part 3 The "Final Solution": The Implementation of Mass Murder 2 edited by Michael Marus, Westpoint: Meckler Press, 1989 pages 500–501.

- ^ Evans, Richard In Hitler's Shadow: West German Historians and the Attempt to Escape from the Nazi Past, New York: Pantheon, 1989 pages 59–60.

- ^ a b Shirer, William The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, New York: Viking page 953

- ^ a b c Palmer, James The Bloody White Baron, New York: Basic Books, 2009 page 253

- ^ Gaddis, John Lewis We Now Know, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998, page 286

- ^

Luce, Henry, ed. (22 December 1941). "How to tell Japs from the Chinese". Life. 11 (25). Chicago: Time Inc.: 81–82. Retrieved 2010-02-19.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Weingartner 1992, p. 55

- ^ Niall Fergusson, "Prisoner Taking and Prisoner Killing in the Age of Total War: Towards a Political Economy of Military Defeat", War in History, 2004, 11 (2): p.182

- ^ Weingartner 1992, p. 54

- ^ a b c Ulrich Straus, The Anguish Of Surrender: Japanese POWs of World War II (excerpts) Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003 ISBN 978-0-295-98336-3, p.116

- ^ Bagby 1999, p. 135

- ^ N. Feraru (May 17, 1950). "Public Opinion Polls on Japan". Far Eastern Survey. 19 (10). Institute of Pacific Relations: 101–103. doi:10.1525/as.1950.19.10.01p0599l.

- ^ Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah (2009). Worse Than War: Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity. PublicAffairs. p. 201. ISBN 0-7867-4656-4.

- ^ Hickey, Michael The Korean War The West Confronts Communism, New York: Overlook Press, 2001 page 87.

- ^ Hickey, Michael The Korean War The West Confronts Communism, New York: Overlook Press, 2001 page 168.

- ^ Hickey, Michael The Korean War The West Confronts Communism, New York: Overlook Press, 2001 page 163.

- ^ Hickey, Michael The Korean War The West Confronts Communism, New York: Overlook Press, 2001 page 163.

- ^ Hickey, Michael The Korean War The West Confronts Communism, New York: Overlook Press, 2001 page 163.

- ^ Nolte, Ernst. "The Past that Will Not Pass" pages 18-22 from Forever In The Shadow Of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Atlantic Highlands, N.J. : Humanities Press, 1993 page 21.

- ^ Evans, Richard J. In Hitler's Shadow New York: Pantheon Books, 1989 pages 37–38; Evans disputes Nolte's evidence for the "rat cage" torture being a common Bolshevik practice.

- ^ Evans, Richard J. In Hitler's Shadow New York: Pantheon Books, 1989 pages 31-32

- ^ Nolte, Ernst "The Past that Will Not Pass" pages 18-22 from Forever In The Shadow Of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Atlantic Highlands, N.J. : Humanities Press, 1993 pages 21-22

- ^ a b Mommsen, Hans "The New Historical Consciousness" pages 114–124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 page 122

- ^ Hirschfeld, Gerhard, "Erasing the Past?", pp. 8-10 in History Today, vol. 37, August 1987, page 8.

- ^ Maier, Charles The Unmasterable Past, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988 page 21

- ^ Ravetto, Kriss The Unmaking of Fascist Aesthetics 2001 Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press page 57.

- ^ Evans, Richard J. In Hitler's Shadow: West German Historians and the Attempt to Escape from the Nazi Past, New York: Pantheon, 1989 page 138

- ^ Müller, Jen-Werner Another Country, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000 page 62.

- ^ Marchetti, Gina (1993). Romance and the "yellow Peril": Race, Sex, and Discursive Strategies in Hollywood Fiction. University of California Press. p. 3.

- ^ "THE UNPARALLELED INVASION". The Jack London Online Collection. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ^ Dunn, J. Allan. The Peril of the Pacific, Off-Trail Publications, 2011. ISBN 978-1-935031-16-1

- ^ See The Call of Cthulhu and other Weird Stories, edited by S. T. Joshi, Penguin Classics, 1999 (p. 390), where Joshi documents Lovecraft's fears that Japan and China will attack the West.

- ^ "1999 World Press Freedom Review". IPI International Press Institute. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ^ a b c d e "The Fall: With a Whimper". Lost Boy's Other-Worldly Collection. 30 September 2007. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ a b c "The Fall: With a Whimper". Erotic Mind Control. 30 September 2007. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "The Fall: With a Whimper". Lost Boy's Other-Worldly Collection. 30 September 2007. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ a b c Stoneman, Rod (8 November 2014). "Far East Fu fighting: The Yellow Peril – Dr Fu Manchu and the Rise of Chinophobia". The Irish Times. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Adrian, Jack "Rohmer, Sax" pages 482-484 from St. James Guide to Horror, Ghost and Gothic Writers edited by David Pringle, Detroit: St. James Press, 1997 page 483.

- ^ Peter X. Feng, Screening Asian Americans, Rutgers University Press, 2002, p.59.

- ^ Richard Jaccoma (1978). "Yellow Peril": The Adventures of Sir John Weymouth-Smythe : a Novel. Richard Marek Publishers. ISBN 0-399-90007-1.

Publications

- Yellow Peril, Collection of British Novels 1895-1913, in 7 vols., edited by Yorimitsu Hashimoto, Tokyo: Edition Synapse. ISBN 978-4-86166-031-3

- Yellow Peril, Collection of Historical Sources, in 5 vols., edited by Yorimitsu Hashimoto, Tokyo: Edition Synapse. ISBN 978-4-86166-033-7

- Baron Suematsu in Europe during the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05): His Battle with Yellow Peril, by Matsumura Masayoshi, translated by Ian Ruxton (lulu.com, 2011)

External links

- http://www.icols.org/pages/ATrumb/ATrumb-Yellow.html

- http://modelminority.com/printout215.html

- http://www.nbportal.com/china/qingdao/

- http://www.sinomedia.net/eurobiz/v200406/regional0406.html

- http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/lab/83/br_2.html

- "Introduction," Gerald Horne, Race War! White Supremacy and the Japanese Attack on the British Empire (New York; London: New York University Press, 2003).

- Yellow Peril in pulp fiction

- Foreign Postcards of the Russo-Japanese War

- "The Unparalleled Invasion" by Jack London, climaxing in total genocide of the Chinese

- Open Season: Anti-Japanese Propaganda during World War II

- Yellow Peril, Collection of British Novels 1895-1913 http://www.aplink.co.jp/synapse/4-86166-031-9.html