Rainbow

A rainbow is an optical and meteorological phenomenon that is caused by reflection, refraction and dispersion of light in water droplets resulting in a spectrum of light appearing in the sky. It takes the form of a multicoloured arc. Rainbows caused by sunlight always appear in the section of sky directly opposite the sun.

Rainbows can be full circles; however, the average observer sees only an arc formed by illuminated droplets above the ground,[1] and centred on a line from the sun to the observer's eye.

In a primary rainbow, the arc shows red on the outer part and violet on the inner side. This rainbow is caused by light being refracted (bent) when entering a droplet of water, then reflected inside on the back of the droplet and refracted again when leaving it.

In a double rainbow, a second arc is seen outside the primary arc, and has the order of its colours reversed, with red on the inner side of the arc.

Overview

A rainbow is not located at a specific distance from the observer, but comes from an optical illusion caused by any water droplets viewed from a certain angle relative to a light source. Thus, a rainbow is not an object and cannot be physically approached. Indeed, it is impossible for an observer to see a rainbow from water droplets at any angle other than the customary one of 42 degrees from the direction opposite the light source. Even if an observer sees another observer who seems "under" or "at the end of" a rainbow, the second observer will see a different rainbow—farther off—at the same angle as seen by the first observer.

Rainbows span a continuous spectrum of colours. Any distinct bands perceived are an artefact of human colour vision, and no banding of any type is seen in a black-and-white photo of a rainbow, only a smooth gradation of intensity to a maximum, then fading towards the other side. For colours seen by the human eye, the most commonly cited and remembered sequence is Newton's sevenfold red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet,[2][3] remembered by the mnemonic, Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain (ROYGBIV).

Rainbows can be caused by many forms of airborne water. These include not only rain, but also mist, spray, and airborne dew.

Visibility

Rainbows can be observed whenever there are water drops in the air and sunlight shining from behind the observer at a low altitude angle. Because of this, rainbows are usually seen in the western sky during the morning and in the eastern sky during the early evening. The most spectacular rainbow displays happen when half the sky is still dark with raining clouds and the observer is at a spot with clear sky in the direction of the sun. The result is a luminous rainbow that contrasts with the darkened background. During such good visibility conditions, the larger but fainter secondary rainbow is often visible. It appears about 10° outside of the primary rainbow, with inverse order of colours.

The rainbow effect is also commonly seen near waterfalls or fountains. In addition, the effect can be artificially created by dispersing water droplets into the air during a sunny day. Rarely, a moonbow, lunar rainbow or nighttime rainbow, can be seen on strongly moonlit nights. As human visual perception for colour is poor in low light, moonbows are often perceived to be white.[4]

It is difficult to photograph the complete semicircle of a rainbow in one frame, as this would require an angle of view of 84°. For a 35 mm camera, a wide-angle lens with a focal length of 19 mm or less would be required. Now that powerful software for stitching several images into a panorama is available, images of the entire arc and even secondary arcs can be created fairly easily from a series of overlapping frames.

From above the earth such as in an airplane, it is sometimes possible to see a rainbow as a full circle. This phenomenon can be confused with the glory phenomenon, but a glory is usually much smaller, covering only 5–20°.

As is evident by the photos on this page, the sky inside of a primary rainbow is brighter than the sky outside of the bow. This is because each raindrop is a sphere and it scatters light in a many-layered stack of coloured discs over an entire circular disc in the sky, but only the edge of the disc, which is coloured, is what is called a rainbow. Alistair Fraser, coauthor of The Rainbow Bridge: Rainbows in Art, Myth, and Science, explains: "Each color has a slightly different-sized disc and since they overlap except for the edge, the overlapping colors give white, which brightens the sky on the inside of the circle. On the edge, however, the different-sized colored discs don't overlap and display their respective colors—a rainbow arc."[5]

Light of primary rainbow arc is 96% polarised tangential to the arch.[6] Light of second arc is 90% polarised.

Number of colours in spectrum or rainbow

A spectrum obtained using a glass prism and a point source is a continuum of wavelengths without bands. The number of colours that the human eye is able to distinguish in a spectrum is in the order of 100.[7] Accordingly, the Munsell colour system (a 20th-century system for numerically describing colours, based on equal steps for human visual perception) distinguishes 100 hues. The apparent discreteness of main colours is an artefact of human perception and the exact number of main colours is a somewhat arbitrary choice.

| Red | Orange | Yellow | Green | Blue | Indigo | Violet |

Newton, who admitted his eyes were not very critical in distinguishing colours,[8] originally (1672) divided the spectrum into five main colours: red, yellow, green, blue and violet. Later he included orange and indigo, giving seven main colours by analogy to the number of notes in a musical scale.[2][9] Newton chose to divide the visible spectrum into seven colours out of a belief derived from the beliefs of the ancient Greek sophists, who thought there was a connection between the colours, the musical notes, the known objects in the Solar System, and the days of the week.[10][11][12]

According to Isaac Asimov, "It is customary to list indigo as a color lying between blue and violet, but it has never seemed to me that indigo is worth the dignity of being considered a separate color. To my eyes it seems merely deep blue."[13] Today, the color Newton associated as "light blue" (~520–490 nm / ~580–610 THz) is referred distinguished as a separate color of either cyan or azure.[14]

The colour pattern of a rainbow is different from a spectrum, and the colours are less saturated. There is spectral smearing in a rainbow owing to the fact that for any particular wavelength, there is a distribution of exit angles, rather than a single unvarying angle.[15] In addition, a rainbow is a blurred version of the bow obtained from a point source, because the disk diameter of the sun (0.5°) cannot be neglected compared to the width of a rainbow (2°). The number of colour bands of a rainbow may therefore be different from the number of bands in a spectrum, especially if the droplets are particularly large or small. Therefore, the number of colours of a rainbow is variable. If, however, the word rainbow is used inaccurately to mean spectrum, it is the number of main colours in the spectrum.

Explanation

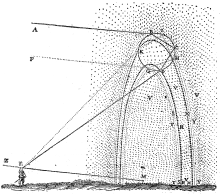

When sunlight encounters a raindrop, part is reflected but part enters, being refracted at the surface of the raindrop. When this light hits the back of the drop, some of it is reflected off the back. When the internally reflected light reaches the surface again, once more some is internally reflected and some is refracted as it exits the drop. (The light that reflects off the drop, exits from the back, or continues to bounce around inside the drop after the second encounter with the surface, is not relevant to the formation of the primary rainbow.) The overall effect is that part of the incoming light is reflected back over the range of 0° to 42°, with the most intense light at 42°.[16] This angle is independent of the size of the drop, but does depend on its refractive index. Seawater has a higher refractive index than rain water, so the radius of a "rainbow" in sea spray is smaller than a true rainbow. This is visible to the naked eye by a misalignment of these bows.[17]

The reason the returning light is most intense at about 42° is that this is a turning point – light hitting the outermost ring of the drop gets returned at less that 42°, as does the light hitting the drop nearer to its centre. There is a circular band of light that all gets returned right around 42°. If the sun were a laser emitting parallel, monochromatic rays, then the luminance (brightness) of the bow would tend toward infinity at this angle (ignoring interference effects). (See Caustic (optics).) But since the sun's luminance is finite and its rays are not all parallel (it covers about half a degree of the sky) the luminance does not go to infinity. Furthermore, the amount by which light is refracted depends upon its wavelength, and hence its colour. This effect is called dispersion. Blue light (shorter wavelength) is refracted at a greater angle than red light, but due to the reflection of light rays from the back of the droplet, the blue light emerges from the droplet at a smaller angle to the original incident white light ray than the red light. Due to this angle, blue is seen on the inside of the arc of the primary rainbow, and red on the outside. The result of this is not only to give different colours to different parts of the rainbow, but also to diminish the brightness. (A "rainbow" formed by droplets of a liquid with no dispersion would be white, but brighter than a normal rainbow.)

The light at the back of the raindrop does not undergo total internal reflection, and some light does emerge from the back. However, light coming out the back of the raindrop does not create a rainbow between the observer and the sun because spectra emitted from the back of the raindrop do not have a maximum of intensity, as the other visible rainbows do, and thus the colours blend together rather than forming a rainbow.[18]

A rainbow does not exist at one particular location. Many rainbows exist; however, only one can be seen depending on the particular observer's viewpoint as droplets of light illuminated by the sun. All raindrops refract and reflect the sunlight in the same way, but only the light from some raindrops reaches the observer's eye. This light is what constitutes the rainbow for that observer. The whole system composed by the sun's rays, the observer's head, and the (spherical) water drops has an axial symmetry around the axis through the observer's head and parallel to the sun's rays. The rainbow is curved because the set of all the raindrops that have the right angle between the observer, the drop, and the sun, lie on a cone pointing at the sun with the observer at the tip. The base of the cone forms a circle at an angle of 40–42° to the line between the observer's head and their shadow but 50% or more of the circle is below the horizon, unless the observer is sufficiently far above the earth's surface to see it all, for example in an aeroplane (see above).[19][20] Alternatively, an observer with the right vantage point may see the full circle in a fountain or waterfall spray.[21]

Variations

Multiple rainbows

Secondary rainbows are caused by a double reflection of sunlight inside the raindrops. Because of the double reflection, light is reflected at all angles from 180° (away from the sun) down to about 50–53°[22]. The center of the secondary rainbow is thus behind the observer, it wraps around the zenith, and the colored arcs are seen about 10° outside of the primary rainbow's. The colors of a secondary rainbow are technically in the same order, with red on the "outside" of the entire effect, but "outside" is "down" to the observer so they are perceived as inverted. The secondary rainbow is fainter than the primary because more light escapes from two reflections compared to one and because the rainbow itself is spread over a greater area of the sky. The dark area of unlit sky lying between the primary and secondary bows is called Alexander's band, after Alexander of Aphrodisias who first described it.[23]

Twinned rainbow

Unlike a double rainbow that consists of two separate and concentric rainbow arcs, the very rare twinned rainbow appears as two rainbow arcs that split from a single base. The colours in the second bow, rather than reversing as in a double rainbow, appear in the same order as the primary rainbow. It is sometimes even observed in combination with a secondary rainbow. The cause of a twinned rainbow is the combination of different sizes of water drops falling from the sky. Due to air resistance, raindrops flatten as they fall, and flattening is more prominent in larger water drops. When two rain showers with different-sized raindrops combine, they each produce slightly different rainbows which may combine and form a twinned rainbow.[24]

Until recently, scientists could make only an educated guess as to why a twinned rainbow does appear, even though extremely rarely. It was thought that most probably non-spherical raindrops produced one or both bows, with surface tension forces keeping small raindrops spherical, while large drops were flattened by air resistance; or that they might even oscillate between flattened and elongated spheroids.[25] However, in 2012 a new technique was used to simulate rainbows, enabling the accurate simulation of non-spherical particles. Besides twinned rainbows, this technique can also be used to simulate many different rainbow phenomena including double rainbows and supernumerary bows.[26]

Meanwhile, the even rarer case of a rainbow split into three branches was observed and photographed in nature.[27]

Full circle rainbow

In theory every rainbow is a circle, but from the ground only its upper half can be seen. Since the rainbow's centre is diametrically opposed to the sun's position in the sky, more of the circle comes into view as the sun approaches the horizon, meaning that the largest section of the circle normally seen is about 50% during sunset or sunrise. Viewing the rainbow's lower half requires the presence of water droplets below the observer's horizon, as well as sunlight that is able to reach them. These requirements are not usually met when the viewer is at ground level, either because droplets are absent in the required position, or because the sunlight is obstructed by the landscape behind the observer. From a high viewpoint such as a high building or an aircraft, however, the requirements can be met and the full circle rainbow can be seen.[28][29] Like a partial rainbow, the circular rainbow can have a secondary bow or supernumerary bows as well.[30] It is also possible to produce the full circle when standing on the ground; e.g., by spraying a water mist from a garden hose while facing away from the sun.[31]

A circular rainbow should not be confused with the glory, which is much smaller in diameter and is created by different optical processes. In the right circumstances a glory and a (circular) rainbow or fog bow can occur together. Another atmospheric phenomenon that may be mistaken for a "circular rainbow" is the 22° halo, which is caused by ice crystals rather than liquid water droplets, and is located around the sun (or moon), not opposite it.

Supernumerary rainbow

A supernumerary rainbow—also known as a stacker rainbow—is an infrequent phenomenon, consisting of several faint rainbows on the inner side of the primary rainbow, and very rarely also outside the secondary rainbow. Supernumerary rainbows are slightly detached and have pastel colour bands that do not fit the usual pattern.

It is not possible to explain their existence using classical geometric optics. The alternating faint rainbows are caused by interference between rays of light following slightly different paths with slightly varying lengths within the raindrops. Some rays are in phase, reinforcing each other through constructive interference, creating a bright band; others are out of phase by up to half a wavelength, cancelling each other out through destructive interference, and creating a gap. Given the different angles of refraction for rays of different colours, the patterns of interference are slightly different for rays of different colours, so each bright band is differentiated in colour, creating a miniature rainbow. Supernumerary rainbows are clearest when raindrops are small and of uniform size. The very existence of supernumerary rainbows was historically a first indication of the wave nature of light, and the first explanation was provided by Thomas Young in 1804.[32]

Reflected rainbow, reflection rainbow

When a rainbow appears above a body of water, two complementary mirror bows may be seen below and above the horizon, originating from different light paths. Their names are slightly different.

A reflected rainbow may appear in the water surface below the horizon.[33] The sunlight is first deflected by the raindrops, and then reflected off the body of water, before reaching the observer. The reflected rainbow is frequently visible, at least partially, even in small puddles.

A reflection rainbow may be produced where sunlight reflects off a body of water before reaching the raindrops (see diagram and [1] ), if the water body is large, quiet over its entire surface, and close to the rain curtain. The reflection rainbow appears above the horizon. It intersects the normal rainbow at the horizon, and its arc reaches higher in the sky, with its centre as high above the horizon as the normal rainbow's centre is below it. Due to the combination of requirements, a reflection rainbow is rarely visible.

Six (or even eight) bows may be distinguished if the reflection of the reflection bow, and the secondary bow with its reflections happen to appear simultaneously.[34][35]

Monochrome rainbow

Occasionally a shower may happen at sunrise or sunset, where the shorter wavelengths like blue and green have been scattered and essentially removed from the spectrum. Further scattering may occur due to the rain, and the result can be the rare and dramatic monochrome or red rainbow.[36]

Higher-order rainbows

In addition to the common primary and secondary rainbows, it is also possible for rainbows of higher orders to form. The order of a rainbow is determined by the number of light reflections inside the water droplets that create it: One reflection results in the first-order or primary rainbow; two reflections create the second-order or secondary rainbow. More internal reflections cause bows of higher orders—theoretically unto infinity.[22] As more and more light is lost with each internal reflection, however, each subsequent bow becomes progressively dimmer and therefore increasingly harder to spot. An additional challenge in observing the third-order (or tertiary) and fourth-order (quaternary) rainbows is their location in the direction of the sun (about 40° and 45° from the sun, respectively), causing them to become drowned in its glare.[37]

For these reasons, naturally occurring rainbows of an order higher than 2 are rarely visible to the naked eye. Nevertheless, sightings of the third-order bow in nature have been reported, and in 2011 it was photographed definitively for the first time.[38][39] Shortly after, the fourth-order rainbow was photographed as well,[40][41] and in 2014 the first ever pictures of the fifth-order (or quinary) rainbow, located in between the primary and secondary bows, were published.[42]

In a laboratory setting, it is possible to create bows of much higher orders. Felix Billet (1808–1882) depicted angular positions up to the 19th-order rainbow, a pattern he called a "rose of rainbows".[43][44] In the laboratory, it is possible to observe higher-order rainbows by using extremely bright and well collimated light produced by lasers. Up to the 200th-order rainbow was reported by Ng et al. in 1998 using a similar method but an argon ion laser beam.[45]

Tertiary and quaternary rainbows should not be confused with "triple" and "quadruple" rainbows—terms sometimes erroneously used to refer to the—much more common—supernumerary bows and reflection rainbows.

Rainbows under moonlight

Moonbows are often perceived as white and may be thought of as monochrome. The full spectrum is present, but our eyes are not normally sensitive enough to see the colours. Long exposure photographs will sometimes show the colour in this type of rainbow.

Fogbow

Fogbows form in the same way as rainbows, but they are formed by much smaller cloud and fog droplets that diffract light extensively. They are almost white with faint reds on the outside and blues inside. The colours are dim because the bow in each colour is very broad and the colours overlap. Fogbows are commonly seen over water when air in contact with the cooler water is chilled, but they can be found anywhere if the fog is thin enough for the sun to shine through and the sun is fairly bright. They are very large—almost as big as a rainbow and much broader. They sometimes appear with a glory at the bow's centre.[46]

Fog bows should not be confused with ice halos, which are very common around the world and visible much more often than rainbows (of any order),[47] yet are unrelated to rainbows.

Circumhorizontal and circumzenithal arcs

The circumzenithal and circumhorizontal arcs are two related optical phenomena similar in appearance to a rainbow, but unlike the latter, their origin lies in light refraction through hexagonal ice crystals rather than liquid water droplets. This means that they are not rainbows, but members of the large family of halos.

Both arcs are brightly coloured ring segments centered on the zenith, but in different positions in the sky: The circumzenithal arc is notably curved and located high above the Sun (or Moon) with its convex side pointing downwards (creating the impression of an "upside down rainbow"); the circumhorizontal arc runs much closer to the horizon, is more straight and located at a significant distance below the Sun (or Moon). Both arcs have their red side pointing towards the sun and their violet part away from it, meaning the circumzenithal arc is red on the bottom, while the circumhorizontal arc is red on top.[48][49]

The circumhorizontal arc is sometimes referred to by the misnomer "fire rainbow". In order to view it, the Sun or Moon must be at least 58° above the horizon, making it a rare occurrence at higher latitudes. The circumzenithal arc, visible only at a solar or lunar elevation of less than 32°, is much more common, but often missed since it occurs almost directly overhead.

Rainbows on Titan

It has been suggested that rainbows might exist on Saturn's moon Titan, as it has a wet surface and humid clouds. The radius of a Titan rainbow would be about 49° instead of 42°, because the fluid in that cold environment is methane instead of water. Although visible rainbows may be rare due to Titan's hazy skies, infrared rainbows may be more common, but an observer would need infrared night vision goggles to see them.[50]

Scientific history

The classical Greek scholar Aristotle (384–322 BC) was first to devote serious attention to the rainbow.[51] According to Raymond L. Lee and Alistair B. Fraser, "Despite its many flaws and its appeal to Pythagorean numerology, Aristotle's qualitative explanation showed an inventiveness and relative consistency that was unmatched for centuries. After Aristotle's death, much rainbow theory consisted of reaction to his work, although not all of this was uncritical."[52]

In Book I of Naturales Quaestiones (c. 65 AD), the Roman philosopher Seneca the Younger discusses various theories of the formation of rainbows extensively, including those of Aristotle. He notices that rainbows appear always opposite to the sun, that they appear in water sprayed by a rower, in the water spat by a fuller on clothes stretched on pegs or by water sprayed through a small hole in a burst pipe. He even speaks of rainbows produced by small rods (virgulae) of glass, anticipating Newton's experiences with prisms. He takes into account two theories: one, that the rainbow is produced by the sun reflecting in each water drop, the other, that it is produced by the sun reflected in a cloud shaped like a concave mirror; he favours the latter. He also discusses other phenomena related to rainbows: the mysterious "virgae" (rods), halos and parhelia.[53]

According to Hüseyin Gazi Topdemir, the Persian physicist and polymath Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen; 965–1039), attempted to provide a scientific explanation for the rainbow phenomenon. In his Maqala fi al-Hala wa Qaws Quzah (On the Rainbow and Halo), al-Haytham "explained the formation of rainbow as an image, which forms at a concave mirror. If the rays of light coming from a farther light source reflect to any point on axis of the concave mirror, they form concentric circles in that point. When it is supposed that the sun as a farther light source, the eye of viewer as a point on the axis of mirror and a cloud as a reflecting surface, then it can be observed the concentric circles are forming on the axis."[54] He was not able to verify this because his theory that "light from the sun is reflected by a cloud before reaching the eye" did not allow for a possible experimental verification.[55] This explanation was later repeated by Averroes,[54] and, though incorrect, provided the groundwork for the correct explanations later given by Kamāl al-Dīn al-Fārisī (1267–1319) and Theodoric of Freiberg (c.1250–1310).[56]

Ibn al-Haytham's contemporary, the Persian philosopher and polymath Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna; 980–1037), provided an alternative explanation, writing "that the bow is not formed in the dark cloud but rather in the very thin mist lying between the cloud and the sun or observer. The cloud, he thought, serves simply as the background of this thin substance, much as a quicksilver lining is placed upon the rear surface of the glass in a mirror. Ibn Sīnā would change the place not only of the bow, but also of the colour formation, holding the iridescence to be merely a subjective sensation in the eye."[57] This explanation, however, was also incorrect.[54] Ibn Sīnā's account accepts many of Aristotle's arguments on the rainbow.[58]

In Song Dynasty China (960–1279), a polymathic scholar-official named Shen Kuo (1031–1095) hypothesized—as a certain Sun Sikong (1015–1076) did before him—that rainbows were formed by a phenomenon of sunlight encountering droplets of rain in the air.[59] Paul Dong writes that Shen's explanation of the rainbow as a phenomenon of atmospheric refraction "is basically in accord with modern scientific principles."[60]

According to Nader El-Bizri, the Persian astronomer, Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi (1236–1311), gave a fairly accurate explanation for the rainbow phenomenon. This was elaborated on by his student, Kamāl al-Dīn al-Fārisī (1267–1319), who gave a more mathematically satisfactory explanation of the rainbow. He "proposed a model where the ray of light from the sun was refracted twice by a water droplet, one or more reflections occurring between the two refractions." An experiment with a water-filled glass sphere was conducted and al-Farisi showed the additional refractions due to the glass could be ignored in his model.[55] As he noted in his Kitab Tanqih al-Manazir (The Revision of the Optics), al-Farisi used a large clear vessel of glass in the shape of a sphere, which was filled with water, in order to have an experimental large-scale model of a rain drop. He then placed this model within a camera obscura that has a controlled aperture for the introduction of light. He projected light unto the sphere and ultimately deduced through several trials and detailed observations of reflections and refractions of light that the colours of the rainbow are phenomena of the decomposition of light. His research had resonances with the studies of his contemporary Theodoric of Freiberg (without any contacts between them; even though they both relied on Aristotle's and Ibn al-Haytham's legacy), and later with the experiments of Descartes and Newton in dioptrics (for instance, Newton conducted a similar experiment at Trinity College, though using a prism rather than a sphere).[61][62][63][64][verification needed][clarification needed]

In Europe, Ibn al-Haytham's Book of Optics was translated into Latin and studied by Robert Grosseteste. His work on light was continued by Roger Bacon, who wrote in his Opus Majus of 1268 about experiments with light shining through crystals and water droplets showing the colours of the rainbow.[65] In addition, Bacon was the first to calculate the angular size of the rainbow. He stated that the rainbow summit can not appear higher than 42° above the horizon.[66] Theodoric of Freiberg is known to have given an accurate theoretical explanation of both the primary and secondary rainbows in 1307. He explained the primary rainbow, noting that "when sunlight falls on individual drops of moisture, the rays undergo two refractions (upon ingress and egress) and one reflection (at the back of the drop) before transmission into the eye of the observer."[67][68] He explained the secondary rainbow through a similar analysis involving two refractions and two reflections.

Descartes' 1637 treatise, Discourse on Method, further advanced this explanation. Knowing that the size of raindrops did not appear to affect the observed rainbow, he experimented with passing rays of light through a large glass sphere filled with water. By measuring the angles that the rays emerged, he concluded that the primary bow was caused by a single internal reflection inside the raindrop and that a secondary bow could be caused by two internal reflections. He supported this conclusion with a derivation of the law of refraction (subsequently to, but independently of, Snell) and correctly calculated the angles for both bows. His explanation of the colours, however, was based on a mechanical version of the traditional theory that colours were produced by a modification of white light.[69][70]

Isaac Newton demonstrated that white light was composed of the light of all the colours of the rainbow, which a glass prism could separate into the full spectrum of colours, rejecting the theory that the colours were produced by a modification of white light. He also showed that red light is refracted less than blue light, which led to the first scientific explanation of the major features of the rainbow.[71] Newton's corpuscular theory of light was unable to explain supernumerary rainbows, and a satisfactory explanation was not found until Thomas Young realised that light behaves as a wave under certain conditions, and can interfere with itself.

Young's work was refined in the 1820s by George Biddell Airy, who explained the dependence of the strength of the colours of the rainbow on the size of the water droplets.[72] Modern physical descriptions of the rainbow are based on Mie scattering, work published by Gustav Mie in 1908.[73] Advances in computational methods and optical theory continue to lead to a fuller understanding of rainbows. For example, Nussenzveig provides a modern overview.[74]

Culture

Rainbows form a significant part of human culture. They occur frequently in mythology, and have been used in the arts. One of the earliest literary occurrences of a rainbow is in Genesis 9, as part of the flood story of Noah, where it is a sign of God's covenant to never destroy all life on earth with a global flood again. The Irish leprechaun's secret hiding place for his pot of gold is usually said to be at the end of the rainbow. This place is impossible to reach, because the rainbow is an optical effect which depends on the location of the viewer. When walking towards the end of a rainbow, it will appear to "move" farther away.

Rainbow flags have been used as a symbol of hope or social change for centuries, featuring as a symbol of the Cooperative movement in the German Peasants' War in the 16th century, as a symbol of peace in Italy, and as a symbol of gay pride and LGBT social movements since the 1970s. In 1994, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and President Nelson Mandela described newly democratic post-apartheid South Africa as the rainbow nation.

Image gallery

-

Rainbow rising over the Atacama Large Millimeter Array.[75]

-

A view of a rainbow from a helicopter

-

Eruption of Castle geyser, Yellowstone National Park, with double rainbow

-

Rainbow after sunlight bursts through after an intense shower in Maraetai, New Zealand

-

Alexander's Band.

See also

- Atmospheric optics

- Circumzenithal arc

- Circumhorizontal arc

- Double Rainbow (viral video)

- Iridescent colours in soap bubbles

- Sun dog

Notes

- ^ "Dr. Jeff Masters Rainbow Site".

- ^ a b Isaac Newton, Optice: Sive de Reflexionibus, Refractionibus, Inflexionibus & Coloribus Lucis Libri Tres, Propositio II, Experimentum VII, edition 1740:

Ex quo clarissime apparet, lumina variorum colorum varia esset refrangibilitate : idque eo ordine, ut color ruber omnium minime refrangibilis sit, reliqui autem colores, aureus, flavus, viridis, cæruleus, indicus, violaceus, gradatim & ex ordine magis magisque refrangibiles. - ^ Gary Waldman, Introduction to Light: The Physics of Light, Vision, and Color, 2002, p. 193:

A careful reading of Newton’s work indicates that the color he called indigo, we would normally call blue; his blue is then what we would name blue-green or cyan. - ^ Walklet, Keith S. (2006). "Lunar Rainbows – When to View and How to Photograph a "Moonbow"". The Ansel Adams Gallery. Archived from the original on May 25, 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

- ^ "Why is the inside of a rainbow brighter than the outside sky?". WeatherQuesting. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ "Rainbow - A polarized arch?". Polarization.com. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ Burch, Paula E. "All About Hand Dyeing Q&A". Retrieved 27 August 2012. (A number between 36 and 360 is in the order of 100)

- ^ Gage, John (1994). "Color and Meaning". Retrieved 2014-12-26.

- ^ Allchin, Douglas. "Newton's Colors". SHiPS Resource Center. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- ^ Hutchison, Niels (2004). "Music For Measure: On the 300th Anniversary of Newton's Opticks". Colour Music. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ^ Newton, Isaac (1704). Opticks.

- ^ “Visible Spectrum Wikipedia Contributors, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia accessed 11/17/2013 available at: Visible spectrum

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1975). Eyes on the Universe: A History of the Telescope. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-395-20716-1.

- ^ Craig F. Bohren (2006). Fundamentals of Atmospheric Radiation: An Introduction with 400 Problems. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3-527-40503-8.

- ^ Cowley, Les. "Primary rainbow colours". Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ "About Rainbows". Eo.ucar.edu. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ Cowley, Les. "Sea Water Rainbow". Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

- ^ Cowley, Les. "Zero order glow". Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved 2011-08-08.

- ^ Anon (7 November 2014). "Why are rainbows curved as semicircles?". Ask the van. The Board of Trustees at the University of Illinois. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ Can you ever see the whole circle of a rainbow? | Earth | EarthSky

- ^ USATODAY.com - Look down on the rainbow

- ^ a b http://www.atoptics.co.uk/rainbows/orders.htm

- ^ See:

- Alexander of Aphrodisias, Commentary on Book IV of Aristotle's Meteorology (also known as: Commentary on Book IV of Aristotle's De Meteorologica or On Aristotle's Meteorology 4), commentary 41.

- Raymond L. Lee and Alistair B. Fraser, The Rainbow Bridge: Rainbows in Art, Myth, and Science (University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2001), pp. 110–111.

- ^ See:

- Alexander Haußmann, "Observation, analysis, and reconstruction of a twinned rainbow", Applied Optics Vol. 54, Issue 4 (2015), pp. B117–B127

- "Researchers unlock secret of the rare 'twinned rainbow,' " ScienceDaily.com, August 6, 2012.

- Sadeghi, Iman; Muñoz, Adolfo; Laven, Philip; Jarosz, Wojciech; Seron, Francisco; Gutierrez, Diego; Jensen, Henrik Wann (February 2012) "Physically-based simulation of rainbows," ACM [Association for Computing Machinery] Transactions on Graphics, 31(1): 3.1–3.12.

- ^ "Atmospheric Optics: Twinned rainbows". Atoptics.co.uk. 2002-06-03. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ "Sadeghi et al. (2012) (computer simulations of rainbows)". Zurich.disneyresearch.com. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ "Triple-split rainbow observed and photographed in Japan, August 2012". blog.meteoros.de. 2015-03-12. Retrieved 2015-03-12.

- ^ "Can you ever see the whole circle of a rainbow? | Earth". EarthSky. 2012-12-15. Retrieved 2013-10-04.

- ^ Philip Laven (2012-08-04). "Circular rainbows". Philiplaven.com. Retrieved 2013-10-04.

- ^ http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap140930.html

- ^ http://www.atoptics.co.uk/fz795.htm

- ^ See:

- Thomas Young (1804) "Bakerian Lecture: Experiments and calculations relative to physical optics," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 94: 1–16; see especially pp. 8–11.

- Atmospheric Optics: Supernumerary Rainbows

- ^ Les Cowley (Atmospheric Optics). "Bows everywhere!". Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ Terje O. Nordvik. "Six Rainbows Across Norway". APOD (Astronomy Picture of the Day). Retrieved 2007-06-07.

- ^ "Atmospheric Optics: Reflection rainbows formation". Atoptics.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ http://atoptics.co.uk/fz1100.htm

- ^ http://www.atoptics.co.uk/rainbows/ord34.htm

- ^ Großmann, Michael (1 Oct 2011). "Photographic evidence for the third-order rainbow". Applied Optics. 50 (28). The Optical Society: F134–F141. Bibcode:2011ApOpt..50F.134G. doi:10.1364/AO.50.00F134. ISSN 1559-128X. PMID 22016237. Retrieved 4 Nov 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "''Triple Rainbows Exist, Photo Evidence Shows'', ScienceDaily.com, Oct. 5, 2011". Sciencedaily.com. 2011-10-06. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ Theusner, Michael (1 Oct 2011). "Photographic observation of a natural fourth-order rainbow". Applied Optics. 50 (28). The Optical Society: F129–F133. Bibcode:2011ApOpt..50F.129T. doi:10.1364/AO.50.00F129. ISSN 1559-128X. PMID 22016236. Retrieved 6 Oct 2011.

- ^ http://www.newscientist.com/blogs/shortsharpscience/2011/10/third-and-fourth-order-rainbow.html

- ^ http://www.weatherscapes.com/quinary/

- ^ Billet, Felix (1868). "Mémoire sur les Dix-neuf premiers arcs-en-ciel de l'eau". Annales scientifiques de l'École Normale Supérieure. 1 (5): 67–109. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Walker, Jearl (1977). "How to create and observe a dozen rainbows in a single drop of water". Scientific American. 237 (July): 138–144 + 154. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0777-138. Retrieved 2011-08-08.

- ^ Ng, P. H.; Tse, M. Y.; Lee, W. K. (1998). "Observation of high-order rainbows formed by a pendant drop". Journal of the Optical Society of America B. 15 (11): 2782. Bibcode:1998JOSAB..15.2782N. doi:10.1364/JOSAB.15.002782.

- ^ See:

- Atmospheric Optics: Fogbow

- James C. McConnel (1890) "The theory of fog-bows," Philosophical Magazine, series 5, 29 (181): 453–461.

- ^ Les Cowley. Observing Halos - Getting Started Atmospheric Optics, accessed 3 December 2013.

- ^ http://www.atoptics.co.uk/halo/cza.htm

- ^ Cowley, Les. "Circumhorizontal arc". Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ^ Science@NASA. "Rainbows on Titan". Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ^ http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/meteorology.3.iii.html#211

- ^ Raymond L. Lee, Alistair B. Fraser (2001). The rainbow bridge: rainbows in art, myth, and science. Penn State Press. p. 109. ISBN 0-271-01977-8.

- ^ Seneca, Lucius Anneus (1 April 2014). Delphi Complete Works of Seneca the Younger (Illustrated). Vol. Book I (Delphi Ancient Classics Book 27 ed.). Delphi Classics.

- ^ a b c Topdemir, Hüseyin Gazi (2007). "Kamal Al-Din Al-Farisi's Explanation of the Rainbow" (PDF). Humanity & Social Sciences Journal. 2 (1): 75–85 [77]. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ a b O'Connor, J.J.; Robertson, E.F. (November 1999). "Kamal al-Din Abu'l Hasan Muhammad Al-Farisi". MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

approximation obtained by his model was good enough to allow him to ignore the effects of the glass container

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Topdemir, Hüseyin Gazi (2007). "Kamal Al-Din Al-Farisi's Explanation of the Rainbow" (PDF). Humanity & Social Sciences Journal. 2 (1): 75–85 [83]. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ Carl Benjamin Boyer (1954). "Robert Grosseteste on the Rainbow". Osiris. 11: 247–258. doi:10.1086/368581.

- ^ Raymond L. Lee, Alistair B. Fraser (2001). The rainbow bridge: rainbows in art, myth, and science. Penn State Press. pp. 141–144 ISBN =0–271–01977–8. ISBN 978-0-271-01977-2.

{{cite book}}: Missing pipe in:|pages=(help) - ^ Sivin, Nathan (1995). Science in Ancient China: Researches and Reflections Brookfield, Vermont: VARIORUM. III: Ashgate Publishing. p. 24.

- ^ Dong, Paul (2000). China's Major Mysteries: Paranormal Phenomena and the Unexplained in the People's Republic. San Francisco: China Books and Periodicals, Inc. p. 72. ISBN 0-8351-2676-5.

- ^ Nader El-Bizri (2005). "Ibn al-Haytham". Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. New York — London: Routledge. pp. 237–240.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Nader El-Bizri (2005). "Optics". In Josef W. Meri (ed.). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Vol. II. New York – London: Routledge. pp. 578–580.

- ^ Nader El-Bizri, (2006). "Al-Farisi, Kamal al-Din". In Oliver Leaman (ed.). The Biographical Encyclopaedia of Islamic Philosophy. Vol. I. London — New York: Thoemmes Continuum. pp. 131–135.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Nader El-Bizri (2006). "Ibn al-Haytham, al-Hasan". In Oliver Leaman (ed.). The Biographical Encyclopaedia of Islamic Philosophy. Vol. I. London — New York: Thoemmes Continuum. pp. 248–255.

- ^ Davidson, Michael W. (August 1, 2003). "Roger Bacon (1214–1294)". Florida State University. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- ^ Raymond L. Lee, Alistair B. Fraser (2001). The rainbow bridge: rainbows in art, myth, and science. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-271-01977-2.

- ^ Lindberg, David C (Summer 1966). "Roger Bacon's Theory of the Rainbow: Progress or Regress?". Isis. 57 (2): 235. doi:10.1086/350116.

- ^ Theodoric of Freiberg (c. 1304–1310) De iride et radialibus impressionibus (On the rainbow and the impressions of radiance).

- ^ Boyer, Carl B. (1952). "Descartes and the Radius of the Rainbow". Isis. 43 (2): 95–98. doi:10.1086/349399.

- ^ Gedzelman, Stanley David (1989). "Did Kepler's Supplement to Witelo Inspire Descartes' Theory of the Rainbow?". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 70 (7): 750. Bibcode:1989BAMS...70..750G. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1989)070<0750:DKSTWI>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0477.

- ^ O'Connor, J.J.; Robertson, E.F. (January 2000). "Sir Isaac Newton". University of St. Andrews. Retrieved 2007-06-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ See:

- G. B. Airy (1838) "On the intensity of light in the neighbourhood of a caustic," Transactions of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 6 (3): 379–403.

- G. B. Airy (1849) "Supplement to a paper , "On the intensity of light in the neighbourhood of a caustic," " Transactions of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 8: 595–600.

- ^ G. Mie (1908) "Beiträge zur Optik trüber Medien, speziell kolloidaler Metallösungen" (Contributions to the optics of turbid media, especially of colloidal metal solutions), Annalen der Physik, 4th series, 25 (3): 377–445.

- ^ Nussenzveig, H. Moyses (1977). "The Theory of the Rainbow". Scientific American. 236 (4): 116. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0477-116.

- ^ "Rainbow Rising". www.eso.org. European Southern Observatory. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

References

- Greenler, Robert (1980). Rainbows, Halos, and Glories. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-19-521833-7.

- Lee, Raymond L. and Alastair B. Fraser (2001). The Rainbow Bridge: Rainbows in Art, Myth and Science. New York: Pennsylvania State University Press and SPIE Press. ISBN 0-271-01977-8.

- Lynch, David K.; Livingston, William (2001). Color and Light in Nature (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77504-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Minnaert, Marcel G.J.; Lynch, David K.; Livingston, William (1993). Light and Color in the Outdoors. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-97935-2.

- Minnaert, Marcel G.J.; Lynch, David K.; Livingston, William (1973). The Nature of Light and Color in the Open Air. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-20196-1.

- Naylor, John; Lynch, David K.; Livingston, William (2002). Out of the Blue: A 24-Hour Skywatcher's Guide. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80925-8.

- Boyer, Carl B. (1987). The Rainbow, From Myth to Mathematics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08457-2.

- Graham, Lanier F., ed. (1976). The Rainbow Book. Berkeley, California: Shambhala Publications and The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. (Large format handbook for the Summer 1976 exhibition The Rainbow Art Show which took place primarily at the De Young Museum but also at other museums. The book is divided into seven sections, each coloured a different colour of the rainbow.)

- De Rico, Ul (1978). The Rainbow Goblins. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27759-1.

External links

- Images by Crayford Manor House Astronomical Society

- National Center for Atmospheric Research, About Rainbows

- Supernumerary and Multiple Rainbows

- Incredible Rainbows Worldwide – slideshow by Life magazine

- Interactive simulation of light refraction in a drop (java applet)

- Spectacular rainbow at Elam Bend (McFall, Missouri)

- Walter Lewin's Discussion on colours and rainbow physics

- Straight Dope on double rainbows

- Rare photo of the ‘end’ of the rainbow

- Rainbow seen through infrared filter and through ultraviolet filter

- Atmospheric Optics website by Les Cowley – Description of multiple types of bows, including: "bows that cross, red bows, twinned bows, coloured fringes, dark bands, spokes", etc.

- Merrifield, Michael. "Rainbows". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.

- Creating Circular and Double Rainbows! - video explanation of basics, shown artificial rainbow at night, second rainbow and circular one.

![Rainbow rising over the Atacama Large Millimeter Array.[75]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/53/Rainbow_Rising.jpg/120px-Rainbow_Rising.jpg)