Forth Bridge

Forth Bridge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 55°59′54″N 3°23′15″W / 55.9984°N 3.3876°W |

| Carries | Rail traffic |

| Crosses | Firth of Forth |

| Locale | Edinburgh, Inchgarvie and Fife, Scotland |

| Maintained by | Balfour Beatty under contract to Network Rail |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Cantilever bridge |

| Total length | 8,094 ft (2,467 m)[1] |

| Width | 120 ft (37 m) at piers[1] 32 ft (9.8 m) at centre[1] |

| Height | 361 ft (110 m) above high water[1] |

| Longest span | 2 of 1,700 feet (520 m)[1] |

| Clearance below | 150 ft (46 m) to high water[1] |

| History | |

| Designer | Sir John Fowler and Sir Benjamin Baker |

| Construction start | 1882 |

| Construction end | 1890 |

| Opened | 4 March 1890 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 190–200 trains per day |

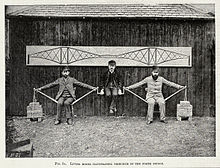

| Official name | The Forth Bridge |

| Type | cultural |

| Criteria | i, iv |

| Designated | 2015 |

| Reference no. | 1485 |

| Location | |

| |

The Forth Bridge is a cantilever railway bridge over the Firth of Forth in the east of Scotland, 9 miles (14 kilometres) west of Edinburgh City Centre. It is considered an iconic structure and a symbol of Scotland, and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It was designed by the English engineers, Sir John Fowler and Sir Benjamin Baker.

Construction of the bridge began in 1882 and it was opened on 4 March 1890 by the Prince of Wales.[2] The bridge spans the Forth between the villages of South Queensferry and North Queensferry and has a total length of 8,296 feet (2,528.7 m). It was the longest single cantilever bridge span in the world until 1917 when the Quebec Bridge in Canada was completed. It continues to be world's second-longest single cantilever span.

The bridge and its associated railway infrastructure is owned by Network Rail Infrastructure Limited.

It is sometimes referred to as the Forth Rail Bridge to distinguish it from the Forth Road Bridge, though this has never been its official name.

Background

Earlier proposals

Prior to the construction of the bridge, ferry boats were used to cross the Firth.[3] In 1806, a pair of tunnels, one for each direction, was proposed, and in 1818 James Anderson produced a design for a three-span suspension bridge close to the site of the present one.[4] Calling for approximately 2,500 tonnes (2,500 long tons; 2,800 short tons) of iron, Wilhelm Westhofen said of it "and this quantity [of iron] distributed over the length would have given it a very light and slender appearance, so light indeed that on a dull day it would hardly have been visible, and after a heavy gale probably no longer to be seen on a clear day either."[5]

Thomas Bouch designed for the Edinburgh and Northern Railway a roll-on/roll-off railway ferry between Granton and Burntisland that opened in 1850, which proved so successful that another was ordered for the Tay.[6] In autumn 1863, a joint project between the North British Railway and Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway, which would merge in 1865, appointed Stephenson and Toner to design a bridge for the Forth, but the commission was given to Bouch around six months later.[7]

It had proven difficult to engineer a suspension bridge that was able to carry railway traffic, and Thomas Bouch, engineer to the North British Railway (NBR) and Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway, was in 1863-1864 working on a single-track girder bridge crossing the Forth near Charlestown, where the river is around 2 miles wide, but mostly relatively shallow.[7][8] The promoters, however, were concerned about the ability to set foundations in the silty river bottom, as borings had gone as deep as 231 feet (70 m) into the mud without finding any rock, but Bouch conducted experiments to demonstrate that it was possible for the silt to support considerable weight.[9] Experiments in late 1864 with weighted caissons achieved a pressure of 5 tons/ft2 on the silt, encouraging Bouch to continue with the design.[9] In August 1865, Richard Hodgson, chairman of the NBR, proposed that the Company invest £18,000 to try a different kind of foundation, as the weighted caissons had not been successful.[10] Bouch proposed using a large pine platform underneath the piers, 80 by 60 by 7 feet (24.4 m × 18.3 m × 2.1 m) (the original design called for a 114 by 80 by 9 feet (34.7 m × 24.4 m × 2.7 m) platform of green beech) weighed down with 10,000 tonnes (9,800 long tons; 11,000 short tons) of pig iron which would sink the wooden platform to the level of the silt.[9] The platform was launched on 14 June 1866 after some difficulty in getting it to move down the greased planks it rested on, and then moored in the harbour for six weeks pending completion.[9][11] The bridge project was aborted just before the platform was sunk as the NBR expected to lose "through traffic" following the amalgamation of the Caledonian Railway and the Scottish North Eastern Railway.[9] In September 1866, a Committee of Shareholders investigating rumours of financial difficulties found that accounts had been falsified, and the chairman and the entire board had resigned by November.[12] By mid-1867 the NBR was nearly bankrupt, and all work on the Forth and Tay bridges was stopped.[13]

The North British Railway took over the ferry at Queensferry in 1867, and completed a rail link from Ratho in 1868, establishing a contiguous link with Fife.[14] Interest in bridging the Forth increased again, and Bouch proposed a stiffened steel suspension bridge on roughly the line of the present rail bridge in 1871, and after careful verification, work started in 1878 on a pier at Inchgarvie.[14]

After Tay Bridge collapsed in 1879, confidence in Bouch dried up and the work stopped.[14] The public inquiry into the disaster, chaired by Henry Cadogan Rothery, found the Tay Bridge to be "badly designed, badly constructed and badly maintained," with Bouch being "mainly to blame" for the defects in construction and maintenance and "entirely responsible" for the defects in design.[15]

After the disaster, which occurred in high winds for which Bouch had not properly accounted, the Board of Trade imposed a lateral wind allowance of 56 lbs/ft2.[16] Bouch's 1871 design had taken a much lower figure of 10 lbs/ft2 on the advice of the Astronomer Royal, although contemporary analysis showed it would likely have stood, but the engineers making the analysis stated that "we do not commit ourselves to an opinion that it is the best possible" [design].[17] Bouch's design was formally abandoned on 13 January 1881, and Sir John Fowler, W. H. Barlow and T. E. Harrison, consulting engineers to the project, were invited to give proposals for a bridge.[18]

Design

Dimensions

It is 1.6 miles (2.5 km) in length, and the double track is elevated 151 ft (46 m) above the water level at high tide. It consists of two main spans of 1,710 ft (521.3 m), two side spans of 680 ft (207.3 m), and 15 approach spans of 168 ft (51.2 m).[19] Each main span consists of two 680 ft (207.3 m) cantilever arms supporting a central 350 feet (106.7 m) span truss. The weight of the bridge superstructure was 50,513 long tons (51,324 t), including the 6.5 million rivets used.[19] The bridge also used 640,000 cubic feet (18,122 m3) of granite.[20]

The three great four-tower cantilever structures are 330 ft (100.6 m) tall,[19] each tower resting on a separate granite pier. These were constructed using 70 ft (21 m) diameter caissons; those for the north cantilever and two on the small uninhabited island of Inchgarvie acted as cofferdams, while the remaining two on Inchgarvie and those for the south cantilever, where the river bed was 91 ft (28 m) below high-water level, used compressed air to keep water out of the working chamber at the base.[21]

Engineering principles

The bridge is built on the principle of the cantilever bridge, where a cantilever beam supports a light central girder, a principle that has been used for thousands of years in the construction of bridges.[22] In order to illustrate the use of tension and compression in the bridge, a demonstration in 1887 had the Japanese engineer Kaichi Watanabe supported between Fowler and Baker sitting in chairs.[23] Fowler and Baker represent the cantilevers, with their arms in tension and the sticks under compression, and the bricks the cantilever end piers which are weighted with cast iron.[24]

Materials

The bridge was the first major structure in Britain to be constructed of steel;[25] its French contemporary, the Eiffel Tower, was built of wrought iron.

Large amounts of steel had become available after the invention of the Bessemer process in 1855. Until 1877 the British Board of Trade had limited the use of steel in structural engineering because the process produced steel of unpredictable strength. Only the Siemens-Martin open-hearth process developed by 1875 yielded steel of consistent quality.

The original design required 42,000 tonnes (41,000 long tons; 46,000 short tons) for the cantilevers only, of which 12,000 tonnes (12,000 long tons; 13,000 short tons) was to come from Messrs. Siemens' steel works in Landore and the remainder from the Steel Company of Scotland's works near Glasgow.[26] When modifications to the design necessitated a further 16,000 tonnes (16,000 long tons; 18,000 short tons), about half of this was supplied by the Steel Company of Scotland and half by Dalzell's Iron and Steel Works in Motherwell.[27] About 4,200 tonnes (4,100 long tons; 4,600 short tons) of rivets came from the Clyde Rivet Company of Glasgow.[27] Around three or four thousand tons of steel was scrapped, and some of which was used for temporary purposes, resulting in the discrepancy between the quantity delivered and the quantity erected.[27]

Approaches

After Dalmeny railway station, the track curves very slightly to the east before coming to the southern approach viaduct.[28] After the railway crosses the bridge, it passes through North Queensferry railway station, before curving to the west, and then back to the east over the Jamestown Viaduct.[28]

Construction

The Bill for the construction of the bridge was passed on 19 May 1882 after an eight day enquiry, the only objections being from rival railway companies.[29] On 21 December of that year, the contract was let to Sir Thomas Tancred, Mr. T. H. Falkiner and Mr. Joseph Philips, civil engineers and contractor, and Sir William Arrol & Co..[30] Arrol was a self-made man, who had been apprenticed to a blacksmith at the age of thirteen before going on to have a highly successful business.[31] Tancred was a professional engineer who had worked with Arrol before, but he would leave the partnership during the course of construction.[32] The steel was produced by Frederick and William Siemens (England) and Pierre and Emile Martin (France), following advances in the furnace designs by the Siemens brothers and improvements on this design by the Martin brothers ,the process of manufacture was thus that it enabled high quality steel to be produced very quickly .[33][34]

Preparations

Offices and stores erected by Arrol in connection with Bouch's bridge were taken possession of for the new works, and would be expanded considerably over time.[35] An accurate survey was taken by Mr. Reginald Middleton, to establish the exact position of the bridge and allow the permanent construction work to commence.[36][37]

The old coastguard station at the Fife end had to be removed to make way for the north-east pier.[38] The rocky shore was levelled to a height of 7 feet (2.1 m) above high water to make way for plant and materials, and huts and other facilities for workmen were set up further inland.[38]

The preparations at South Queensferry were of a much more substantial character, and required the steep hillside to be terraced.[38] Wooden huts and shops for the workmen were put up, as well as more substantial brick houses for the foremen and tenements for leading hands and gangers.[38] Drill roads and workshops were built, as well as a drawing loft 200 by 60 feet (61 by 18 m) to allow full size drawings and templates to be laid out.[38] A cable was also laid across the Forth to allow telephone communication between the centres at Queensferry, Inchgarvie, and Fife, and girders from the collapsed Tay Bridge were laid across the railway to the west in order to allow access to the ground there.[38] Near the shore a sawmill and cement store were erected, and a substantial jetty around 2,100 feet (640 m) long was started early in 1883, and extended as necessary, and sidings were built to bring railway vehicles among the shops, and cranes set up to allow the loading and movement of material delivered by rail.[38]

In April 1883, construction of a landing stage at Inchgarvie commenced.[38] Extant buildings, including fortifications built in the 15th century, were roofed over to increase the available space, and the rock at the west of the island was cut down to a level 7 feet (2.1 m) above high water, and a seawall was built to protect against large waves.[38] In 1884 a compulsory purchase order was obtained for the island, as it was found that previously available area enclosed by the four piers of the bridge was insufficient for the storage of materials.[38] Iron staging reinforced wood in heavily used areas was put up over the island, eventually covering around 10,000 square yards (8,400 m2) and using over 1,000 tonnes (980 long tons; 1,100 short tons) of iron.[39]

Movement of materials

The bridge uses 55,000 tonnes (54,000 long tons; 61,000 short tons) of steel and 140,000 cubic yards (110,000 m3) of masonry.[39] Many materials, including granite from Aberdeen, Arbroath rubble, sand, timber, and sometimes coke and coal, could be taken straight to the centre where they were required.[39] Steel was delivered by train and prepared at the yard at South Queensferry before being painted with boiled linseed oil before being taken to where it was needed by barge.[39] The cement used was Portland cement manufactured on the Medway.[40] It required to be stored before it was able to be used, and up to 1,200 tonnes (1,200 long tons; 1,300 short tons) of cement could be kept in a barge, formerly called the Hougomont that was moored off Queensferry.[40]

For a time a paddle steamer was hired for the movement of workers, but after a time it was replaced with one capable of carrying 450 men, and the barges were also used for people carrying.[39] Special trains were run from Edinburgh and Dunfermline, and a steamer ran to Leith in the summer.[39]

Circular Piers

The three towers of the cantilever are each seated on four circular piers. Since the foundations were required to be constructed at or below sea level, they were excavated with the assistance of caissons and cofferdams.[40]

Six caissons were excavated by the pneumatic process, by the French contractor L. Coisea.[41][42] This process used a positive air pressure inside a sealed caisson to allow dry working conditions at depths of up to 89 feet (27 m).[42][43]

These caissons were constructed and assembled in Glasgow by the Arrol Brothers, namesakes of but unconnected to W. Arrol, before being dismantled and transported to Queensferry.[41][44] The caissons were then built up to a large extent before being floated to their final resting-places.[45] The first caisson, for the south-west pier at Queensferry was launched on 26 May 1884, and the last caisson was launched on 29 May 1885 for the south-west pier at Inchgarvie.[45] When the caissons had been launched and moored, they were extended upwards with a temporary portion in order to keep water out and allow the granite pier to be built when in place.[45]

Above the foundations each of which is different to suit the different sites, is a tapered circular granite pier with a diameter of 55 feet (17 m) at the bottom and a height of 36 feet (11 m).[46]

Inchgarvie

The rock on which the two northern piers at Inchgarvie are located is submerged at high water, and of the other two piers, the site of eastern one is about half submerged and the western one three-quarters submerged.[47] This meant work initially had to be done at low tide.[47]

The southern piers on Inchgarvie are sited on solid rock with a slope of around 1 in 5, so the rock was prepared with concrete and sandbags to make a landing-spot for the caissons.[48][49] Excavation was carried out by drilling and blasting

Fife

Once the positions of the piers had been established, the first task at Fife was to level the site of the northernmost piers, a bedrock of whinstone rising to a level of 10 to 20 feet (3.0 to 6.1 m) above high water, to a height of 7 feet (2.1 m) above high water.[40] The south piers at Fife are sited on rock sloping into the sea, and the site was prepared by diamond drilling holes for explosive charges and blasting the rock.[47]

Queensferry

The four Queensferry caissons were all sunk by the pneumatic method, and are identical in design except for differences in height.[41] A T shaped jetty was built at the site of the Queensferry piers, to allow one caisson to be attached to each corner, and when launched the caissons were attached to the jetty and permitted to rise and fall with the tide.[45][50] Excavation beneath the caissons was generally only carried out at high tide when the caisson was supported by buoyancy, and then when the tide fell the air pressure was reduced in order to allow the caisson to sink down, and digging would begin anew.[43]

The north-west caisson was towed into place in December 1884, but an exceptionally low tide on New Year's Day 1885 caused the caisson to sink into the mud of the river bed and adopt a slight tilt.[48] When the tide rose, it flooded over the lower edge, filling the caisson with water, and when the tide fell but the water did not drain from the caisson, its top-heaviness caused to tilt further.[48] Plates were bolted on by divers to raise the edge of the caisson above water level, and the caisson was reinforced with wooden struts as water was pumped out, but pumping took place too quickly and the water pressure tore a hole between 25 and 30 feet (7.6 and 9.1 m) long.[48] It was decided to construct a "barrel" of large timbers inside the caisson to reinforce it, and it was ten months before the caisson could be pumped out and dug free.[48] The caisson was refloated on October 19, 1885, and then moved into position and sunk with suitable modifications.[48]

Approach viaducts

The approach viaducts to the north and south had to be carried at 130 feet 6 inches (39.78 m) above the level of high water, and it was decided to build them at a lower level and then raise them in tandem with the construction of the masonry piers.[51] The two viaducts have fifteen spans between them, each one 168 feet (51 m) long and weighing slightly over 200 tonnes (200 long tons; 220 short tons).[51] Two spans are attached together to make a continuous girder, with an expansion joint between each pair of spans.[51] Due to the slope of the hill under the viaducts, the girders were assembled at different heights, and only joined when they had reached the same level.[52] Lifting was done using large hydraulic rams, and took place in increments of around 3 feet 6 inches (1.07 m) every four days.[52]

Building the cantilevers

The tubular members were constructed in the No. 2 workshop further up the hill at Queensferry.[53] To bend plates into the required shape, they were first heated in a gas furnace, and then pressed into the correct curve.[53] The curved plates were then assembled on a mandrel, and holes drilled for rivets, before they were marked individually and moved to the correct location to be added to the structure.[53] Lattice members and other parts were also assembled at South Queensferry, using cranes and highly efficient hydraulic rivetters.[54]

Opening

The bridge was completed in December 1889, and load testing of the completed bridge was carried out on 21 January 1890. Two trains, each consisting of three heavy locomotives and 50 wagons loaded with coal, totalling 1,880 tons in weight, were driven slowly from South Queensferry to the middle of the north cantilever, stopping frequently to measure the deflection of the bridge. This represented more than twice the design load of the bridge: the deflection under load was as expected.[21] A few days previously there had been a violent storm, producing the highest wind pressure recorded to date at Inchgarvie, and the deflection of the cantilevers had been less than 25 mm (1 in). The first complete crossing took place on 24 February, when a train consisting of two carriages carrying the chairmen of the various railway companies involved made several crossings. The bridge was opened on 4 March 1890 by the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, who drove home the last rivet, which was gold plated and suitably inscribed.[20] The key for the official opening was made by Edinburgh silversmith John Finlayson Bain, commemorated in a plaque on the bridge.

Accidents and deaths

At its peak, approximately 4,600 workers were employed in its construction. Wilhelm Westhofen recorded in 1890 that 57 lives were lost; but in 2005 the Forth Bridge Memorial Committee was set up to erect a monument to the briggers, and a team of local historians set out to name all those who died.[55] As of 2009, 73 deaths have been connected with the construction of the bridge and its immediate aftermath.[56] It is thought that the figure of 57 deaths excluded those who died working on the approaches to the bridge, as those parts were completed by a subcontractor, as well as those who died after the Sick and Accident Club stopped.[56] Of the 73 recorded deaths, 38 were as a result of falling, 9 of being crushed, 9 drowned, 8 struck by a falling object, 3 died in a fire in a bothy, 1 of caisson disease, and the cause of five deaths is unknown.[57]

The Sick and Accident Club was founded in the summer of 1883, and membership was compulsory for all contractors employees.[58] It would provide medical treatment to men and sometimes their families, and pay them if they were unable to work.[58] The Club also paid for funerals within certain limits, and would provide grants to the widows of men killed or the wives of those permanently disabled.[58] Eight men were saved from drowning by rowing boats positioned in the river under the working areas.[39]

Later history

Race to the North

Before the opening of the Forth Bridge, the railway journey from London to Aberdeen had taken about 13 hours running from Euston and using the London and North Western Railway and Caledonian Railway on a west coast route. With competition opened up along the east coast route from the Great Northern, North Eastern and North British railways and starting from King's Cross, unofficial racing took place between the two consortia, reducing the journey time to about 8½ hours on the overnight runs. This reached a climax in 1895 with sensational daily press reports about the "Race to the North". When race fever subsided the journey times became around 10½ hours.[59]

World Wars

In the First World War British sailors would time their departures or returns to the base at Rosyth by asking when they would pass under the bridge.[60] This practice continued at least up to the 1990s. In both wars the anchorage at Rosyth extended eastwards beyond the bridge.

The first German air attack on Britain in the Second World War took place over the Forth Bridge, six weeks into the war, on 16 October 1939. Although known as the "Forth Bridge Raid", the bridge was not the target and not damaged. In all, 12 German Junkers Ju 88 bombers led by two reconnaissance Heinkel He 111s from Westerland on the island of Sylt, 460 miles (400 nmi; 740 km) away, reached the Scottish coast in four waves of three.[61] The target of the attack was shipping from the Rosyth naval base in the Forth, close to the bridge. The Germans were hoping to find HMS Hood, the largest capital ship in the Royal Navy. At this time, the Luftwaffe's rules of engagement restricted action to targets on water and not in the dockyard. Although HMS Repulse was in Rosyth, the attack was concentrated on the cruisers HMS Edinburgh and HMS Southampton, the carrier HMS Furious and the destroyer HMS Jervis.[62] Three ships were damaged in the raid: the destroyer HMS Mohawk and two cruisers, HMS Southampton and HMS Edinburgh. Sixteen Royal Navy crew died and a further 44 were wounded, although this information was not made public at the time.[63]

Spitfires from RAF 603 "City of Edinburgh" Squadron intercepted the raiders and during the attack shot down the first German aircraft downed over Britain in the war.[64] One bomber came down in the water off Port Seton on the East Lothian coast, and another off Crail on the coast of Fife. After the war it was learned that a third bomber had come down in Holland as a result of damage inflicted during the raid. Later in the month, a reconnaissance Heinkel 111 crashed near Humbie in East Lothian and photographs of this crashed plane were, and still are, used erroneously to illustrate the raid of 16 October, thus sowing confusion as to whether a third aircraft had been brought down.[65] Members of the bomber crew at Port Seton were rescued and made prisoners-of-war. Two bodies were recovered from the Crail wreckage and, after a full military funeral with firing party, were interred in Portobello cemetery, Edinburgh. The body of the gunner was never found.[66] A wartime propaganda film, "Squadron 992", made by the GPO Film Unit after the raid recreated it and conveyed the false impression that the main target was the bridge.[67]

Ownership

Before the opening of the bridge, the North British Railway (NBR) had lines on both sides of the Firth of Forth between which trains could not pass except by running at least as far west as Alloa and using the lines of a rival company. The only alternative route between Edinburgh and Fife involved the ferry at Queensferry, which was purchased by the NBR in 1867. Accordingly, the NBR sponsored the Forth Bridge project which would give them a direct link independent of the Caledonian Railway.[68] A conference at York in 1881 set up the Forth Bridge Railway Committee, to which the NBR contributed 35% of the cost. The remaining money came from three English railways, who ran trains from London over NBR tracks. The Midland Railway, which connected to the NBR at Carlisle and which owned the route to London (St Pancras), contributed 30% and the remainder came equally from the North Eastern Railway and the Great Northern Railway, who between them owned the route between Berwick-upon-Tweed and London (King's Cross), via Doncaster. This body undertook to construct and maintain the bridge.[69]

In 1882 the NBR were given powers to purchase the bridge, which it never exercised.[68] At the time of the 1923 Grouping, the bridge was still jointly owned by the same four railways,[70][71] and so it became jointly owned by these companies' successors, the London Midland and Scottish Railway (30%) and the London and North Eastern Railway (70%).[72] The Forth Bridge Railway Company was named in the Transport Act 1947 as one of the bodies to be nationalised and so became part of British Railways on 1 January 1948.[73] Under the Act, Forth Bridge shareholders would receive £109 of British Transport stock for each £100 of Forth Bridge Debenture stock; and £104-17-6d (£104.87½) of British Transport stock for each £100 of Forth Bridge Ordinary stock.[74][75]

Visitor centre plans

Network Rail plans to add a visitor centre to the bridge, which would include a viewing platform on top of the North Queensferry side, or a bridge climbing experience to the South Queensferry side.[76] In December 2014 it was announced Arup had been awarded the design contract for the project.[77]

World Heritage Site status

UNESCO inscribed the bridge as a World Heritage Site on 5 July 2015, recognising it as "an extraordinary and impressive milestone in bridge design and construction during the period when railways came to dominate long-distance land travel." It is the sixth World Heritage Site to be inscribed in Scotland.[78]

Maintenance

The bridge has a speed limit of 50 miles per hour (80 km/h) for high-speed trains and diesel multiple units, 40 miles per hour (64 km/h) for ordinary passenger trains and 30 miles per hour (48 km/h) for freight trains.[79][80] The route availability code is RA8, but freight trains above a certain size must not pass each other on the bridge.[81]

Up to 190–200 trains per day crossed the bridge in 2006.[82] The Forth Bridge needs constant maintenance and the ancillary works for the bridge include not only a maintenance workshop and yard but a railway "colony" of some fifty houses at Dalmeny Station. The track on the bridge is of "waybeam" construction: 12 inch square baulks of timber 6 metres long are bolted into steel troughs in the bridge deck and the rails are fixed on top of these sleepers. Prior to 1992 the rails on the bridge were of a unique "Forth Bridge" section.

"Painting the Forth Bridge" is a colloquial expression for a never-ending task, coined on the erroneous belief that at one time in the history of the bridge repainting was required and commenced immediately upon completion of the previous repaint.[83] Such a practice never existed, as weathered areas were given more attention, but there was a permanent maintenance crew.[84]

Restoration

Floodlighting was installed in 1991, and the track was renewed between 1992 and 1995.[84] The bridge was costing British Rail £1 million a year to maintain, and they announced that the schedule of painting would be interrupted to save money, and the following year, upon privatisation, Railtrack took over.[84] A £40 million package of works commenced in 1998, and in 2002 the responsibility of the bridge was passed to Network Rail.[84]

Work started in 2002 to repaint the bridge fully for the first time in its history, in a £130 million contract awarded to Balfour Beatty.[85][86] Up to 4,000 tonnes (3,900 long tons; 4,400 short tons) of scaffolding was on the bridge at any time, and computer modelling was used to analyse the additional wind load on the structure.[87] The bridge was encapsulated in a climate controlled membrane to give the proper conditions for the application of the paint.[88] All previous layers of paint were removed using copper slag fired at up to 200 miles per hour (320 km/h), exposing the steel and allowing repairs to be made.[88][89] The paint, developed specifically for the bridge by Leigh Paints, consisted of a system of three coats derived from that used in the North Sea oil industry.[88] 240,000 litres (53,000 imp gal; 63,000 US gal) of paint was applied to 255,000 square metres (2,740,000 sq ft) of the structure, and it is not expected to need repainting for at least 20 years.[86][88] The top coat can be reapplied indefinitely, minimising future maintenance work.[90]

In a report produced by JE Jacobs, Grant Thornton and Faber Maunsell in 2007 which reviewed the alternative options for a second road crossing, it was stated that "Network Rail has estimated the life of the bridge to be in excess of 100 years. However, this is dependant [sic] upon NR’s inspection and refurbishment works programme for the bridge being carried out year on year".[91]

Banknotes, coins

A representation of the Forth Bridge appears on the 2004 issue one pound coin.[92]

The 2007 series of banknotes issued by the Bank of Scotland depicts different bridges in Scotland as examples of Scottish engineering, and the £20 note features the Forth Bridge.[93]

In 2014 Clydesdale Bank announced the introduction of Britain's second polymer banknote, a £5 note featuring Sir William Arrol and the Forth Bridge (the first was issued by Northern Bank in 2000). It will be introduced in 2015 to commemorate the 125th anniversary of the opening of the bridge, and its nomination to become a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[94]

Popular culture

- There is a scene on the bridge in Alfred Hitchcock's 1935 film The 39 Steps and it is featured even more prominently in the 1959 remake of the film.[95]

- The bridge featured in posters advertising the soft drink Barr's Irn-Bru, with the slogan: Made in Scotland, from girders[96]

- The bridge was lit up red for BBC's Comic Relief in 2005.[97]

- A countdown clock to the millennium was placed on the bridge in 1998.[98]

- The Bridge, a novel by Iain Banks, is mainly set on a fictionalised version of the bridge.[99]

- In Alan Turing's most famous paper about artificial intelligence, one of the challenges put to the subject of an imagined Turing test is "Please write me a sonnet on the subject of the Forth Bridge". The test subject in Turing's paper answers, "Count me out on this one. I never could write poetry".[100]

- Sébastien Foucan, a French freerunner, crawled along one of the highest points of the bridge, without a harness, for the Jump Britain documentary made by Channel 4.[101]

- The bridge is included in the video game Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas by Edinburgh-based developer Rockstar North. Renamed the Kincaid Bridge, it serves as the main railway bridge of the fictional city of San Fierro, and appears alongside a virtual Forth Road Bridge.[102]

- 'Painting the Forth Bridge' is an expression of an endless/repetitive, Sisyphean task. -On the assumption that once the painting is completed, it would be time to start again.

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f "Forth Bridge". NetworkRail. Network Rail. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Cole 2011, p. 42

- ^ McKean 2006, p. 58

- ^ Harding, Gerard & Ryall 2006, p. 2

- ^ Westhofen 1890, p. 1

- ^ McKean 2006, pp. 58–59

- ^ a b McKean 2006, p. 62

- ^ Paxton 1990, pp. 24–27

- ^ a b c d e Paxton 1990, p. 29

- ^ McKean 2006, pp. 73–74

- ^ McKean 2006, p. 77

- ^ McKean 2006, p. 78

- ^ McKean 2006, p. 81

- ^ a b c Paxton 1990, p. 32

- ^ Summerhayes 2010, p. 7

- ^ Paxton 1990, p. 41

- ^ Paxton 1990, pp. 44–45

- ^ Paxton 1990, pp. 47–49

- ^ a b c "Forth Rail Bridge Facts & Figures". Forth Bridges Visitors Centre Trust. Retrieved 21 April 2006.[dead link]

- ^ a b Overview of Forth Bridge. The Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 21 April 2006

- ^ a b "Description and History of the Bridge". The Times. No. 32950. London. 4 March 1890. p. 13.

- ^ Westhofen 1890, p. 4

- ^ "Kaichi Watanabe". University of Glasgow. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ Westhofen 1890, p. 6

- ^ Blanc, McEvoy & Plank 2003, p. 16

- ^ Westhofen 1890, pp. 36–37

- ^ a b c Westhofen 1890, p. 37

- ^ a b "Forth Bridge" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Paxton 1990, p. 67

- ^ Paxton 1990, pp. 67–68

- ^ Paxton 1990, pp. 68–70

- ^ Paxton 1990, p. 70

- ^ http://www.railway-technology.com/projects/forth-rail-bridge-firth-scotland/

- ^ http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/article-202991/iron-and-steel-industry

- ^ Westhofen 1890, p. 12

- ^ Westhofen 1890, pp. 12–13

- ^ "Triangulation & measurements at the Forth bridge". worldcat.org. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Westhofen 1890, p. 13

- ^ a b c d e f g Westhofen 1890, p. 14

- ^ a b c d Westhofen 1890, p. 17

- ^ a b c Westhofen 1890, p. 22

- ^ a b Westhofen 1890, p. 71

- ^ a b Westhofen 1890, p. 27

- ^ "Arrol Brothers". glasgowwestaddress.co.uk. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d Westhofen 1890, p. 23

- ^ Westhofen 1890, p. 31

- ^ a b c Westhofen 1890, p. 18

- ^ a b c d e f Westhofen 1890, p. 26

- ^ Westhofen 1890, p. 20

- ^ Westhofen 1890, p. 21

- ^ a b c Westhofen 1890, p. 32

- ^ a b Westhofen 1890, p. 33

- ^ a b c Westhofen 1890, p. 38

- ^ Westhofen 1890, p. 39

- ^ Wills 2009, p. 82

- ^ a b Wills 2009, p. 86

- ^ Wills 2009, p. 90

- ^ a b c Paxton 1990, p. 136

- ^ Nock 1958, pp. 64, 66

- ^ A North Sea Diary 1914–1918, p. 80

- ^ W. Simpson, Spitfires Over Scotland, G C Books Ltd., 2010 ISBN 978-1-872350-44-8, p. 84

- ^ W. Simpson, Spitfires Over Scotland, p. 92

- ^ http://www.educationscotland.gov.uk/scotlandshistory/20thand21stcenturies/worldwarii/airattack/index.asp

- ^ "Air attack in the Firth of Forth - World War II (1939-45) - Scotlands History". Ltscotland.org.uk. 16 October 1939. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ^ W. Simpson, Spitfires Over Scotland, p. 108

- ^ W. Simpson, Spitfires Over Scotland, pp. 100 & 109

- ^ http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/1364857/index.html

- ^ a b Awdry, Christopher (1990). Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies. London: Guild Publishing. p. 132. CN 8983.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Thomas, John; Turnock, David (1989). Thomas, David St John; Patmore, J. Allan (eds.). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume XV — North of Scotland. Newton Abbot: David St John Thomas. p. 71. ISBN 0-946537-03-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Conolly, W. Philip (January 1976). British Railways Pre-Grouping Atlas and Gazetteer (5th ed.). Shepperton: Ian Allan. p. 49. ISBN 0-7110-0320-3. EX/0176.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Whitehouse, Patrick; Thomas, David St John (1989). LNER 150: The London and North Eastern Railway — A Century and a Half of Progress. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. p. 21. ISBN 0-7153-9332-4. 01LN01.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Hughes, Geoffrey (1987) [1986]. LNER. London: Guild Publishing/Book Club Associates. pp. 33–34. CN 1455.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ His Majesty's Government (6 August 1947). "Transport Act 1947 (10 & 11 Geo. 6 ch. 49)" (PDF). London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 145. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

{{cite web}}:|chapter=ignored (help) - ^ Transport Act 1947, fourth schedule, p. 148

- ^ Bonavia, Michael R. (1981). British Rail: The First 25 Years. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. p. 10. ISBN 0-7153-8002-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "The Forth Bridge Experience: An executive summary of its feasibility" (PDF). Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ^ "Design For £15m Forth Bridge Visitor Won by Arup". OBAS Group.

- ^ "Forth Bridge given world heritage status". BBC News. 5 July 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ Harding, Gerard & Ryall 2006, p. 11

- ^ Paxton 1990, p. 91

- ^ "Forth Bridge and Associated Rail Network". Transport Scotland. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ^ "The Forth Bridge". Forth Bridges Visitors Centre Trust. Retrieved 21 April 2006.

- ^ "be like painting the Forth Bridge". theFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ a b c d Glen, Bowman & Andrew 2012, p. 15

- ^ Glen, Bowman & Andrew 2012, p. 16

- ^ a b http://www.scotsman.com/lifestyle/men-of-steel-the-men-who-maintain-the-forth-rail-bridge-1-1976605

- ^ Glen, Bowman & Andrew 2012, p. 18

- ^ a b c d Glen, Bowman & Andrew 2012, p. 19

- ^ McKenna, John (19 February 2008). "Painting of Forth bridge to end". New Civil Engineer. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ Glen, Bowman & Andrew 2012, p. 20

- ^ "Forth Replacement Crossing - Report 1 - Assessment of Transport Network". Transport Scotland. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ^ "The United Kingdom £1 Coin". The Royal Mint. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ^ "Banknote Design Features : Bank of Scotland Bridges Series". The Committee of Scottish Clearing Bankers. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- ^ "UK's first plastic banknote introduced to commemorate Forth Bridge's UNESCO nomination". Herald Scotland. 22 May 2014.

- ^ "The LNER in Books, Film, and TV". Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "A Glow in the Dark Forth Bridge? Easy For Boats to Spot at Least!". Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "Dunfermline.info The Historic City". Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "Forth Road Bridge 50th year ad banner plan slammed - The Scotsman". The Scotsman. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "The Worlds of Iain Banks". Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ Turing, Alan (October 1950). "Computing Machinery and Intelligence". Mind. 59 (236): 433–460. doi:10.1093/mind/LIX.236.433. ISSN 1460-2113. JSTOR 2251299. S2CID 14636783.

- ^ "Jump Britain · British Universities Film & Video Council". Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "Grand Theft Auto tour of Scotland as councillors of Hawick 'disgusted' by use of name for GTA V's drug district - Gaming - Gadgets & Tech". The Independent. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

Sources

- Blanc, Alan; McEvoy, Michael; Plank, Roger (2003). Architecture and Construction in Steel. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-82839-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cole, Beverly (2011). Trains. Potsdam, Germany: H.F.Ullmann. ISBN 978-3-8480-0516-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Glen, Ann; Bowman, Craig; Andrew, John (2012). Forth Bridge: Restoring an Icon. Lily Publications. ISBN 978-1-907945-19-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harding, J. E.; Gerard, Parke; Ryall, M (2006). Bridge Management: Inspection, maintenance, assessment and repair. CRC Press. ISBN 9780203973547.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - MacKay, Sheila (2011). The Forth Bridge: A Picture History. Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-84158-935-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McKean, Charles (2006). Battle for the North. Granta Books. ISBN 978-1-86207-852-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nock, Oswald S. (1958). The Railway Race to the North. Ian Allan.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Paxton, Roland (1990). 100 Years of the Forth Bridge. Thomas Telford. ISBN 9780727716002.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Summerhayes, Stuart (2010). Design Risk Management. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444318906.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Westhofen, Wilhem (1890). The Forth Bridge. Offices of "Engineering".

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wills, Elspeth M. (2009). The Briggers: The Story of the Men Who Built the Forth Bridge. Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-84158-761-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- 40 black-and-white photographs of the construction of the Forth Bridge taken from 1886–1887 by Philip Phillips at National Library of Scotland

- Forth Bridges Visitor Centre Trust - Rail Bridge Main

- Forth Bridge Memorial

- Forth Rail Bridge at Structurae

- Scottish Poetry Library: Poetry Map of Scotland (Firth of Forth): The Construction of the Forth Bridge, 1882–1890, by Colin Donati

- Clarence Winchester, ed (1935), "The Forth Bridge", Railway Wonders of the World, pp. 432–441

{{citation}}:|author=has generic name (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)

- Bridges completed in 1890

- Cantilever bridges

- Category A listed buildings in Edinburgh

- Category A listed buildings in Fife

- Transport in Edinburgh

- Railway bridges in Scotland

- Listed bridges in Scotland

- Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks

- World Heritage Sites in Scotland

- Bridges in Fife

- Bridges in Edinburgh

- Firth of Forth

- List of English People