Martin Luther

- For other people named Martin Luther, see Martin Luther (disambiguation).

| ||

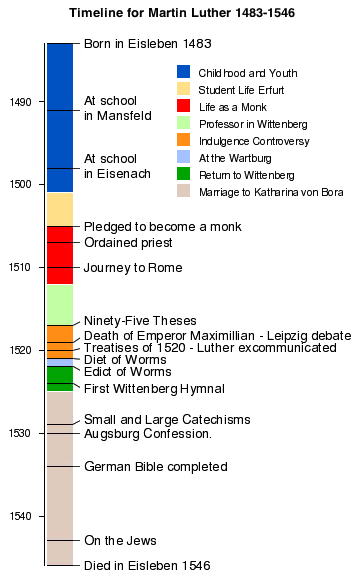

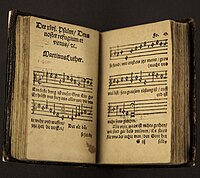

Martin Luther (November 10, 1483 – February 18, 1546) was a German monk,[1] priest, professor, theologian, and church reformer. His teachings inspired the Reformation and deeply influenced the doctrines and culture of the Lutheran and Protestant traditions, as well as the course of Western civilization. Luther's hymns, including his best-known "A Mighty Fortress is Our God", inspired the development of congregational singing within Christianity.[2] His marriage on June 13, 1525, to Katharina von Bora reintroduced the practice of clerical marriage within many Christian traditions.[3]

Martin Luther's translation of the Bible furthered the development of a standard version of the German language and added several principles to the art of translation.[4] His translation significantly influenced the English King James Bible.[5] (See Luther's Bible translation below.) Due to the recently developed printing press, his writings were widely read, influencing many subsequent Protestant Reformers and thinkers, giving rise to diversifying Protestant traditions in Europe and elsewhere.[6] Today, nearly seventy million Christians belong to Lutheran churches worldwide,[7] with some four hundred million Protestant Christians[8] tracing their history back to Luther's reforming work.

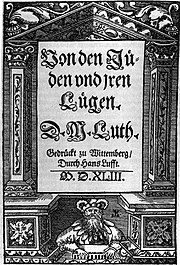

Luther is also known for his writings about the Jews, in which he proposed that their homes be destroyed, synagogues and schools burned, money confiscated, and rights and liberties curtailed.[9] These views were given "full publicity"[10] by the Nazis in Germany in 1933–45.[11] (See Luther and Antisemitism below.)

|

Early life

Luther was born to Hans and Margarethe Luther (Ziegler), on November 10, 1483, in Eisleben, Germany. He was baptized the next morning, on the feast day of St. Martin of Tours, after whom he was named. His family moved to Mansfeld in 1484, where his father first worked in, then later operated, copper mines.[12] Having risen from the peasantry, Hans Luther was determined to see his eldest son become a lawyer. Luther was sent to schools in Mansfeld and later, in 1497, Magdeburg, where he attended a school operated by a lay group called the Brethren of the Common Life. In 1498, he attended school in Eisenach.[13]

In 1501, at the age of seventeen, he entered the University of Erfurt where he played the lute and was nicknamed "the philosopher." He received a B.A. in 1502 and an M.A. in 1505, placing second out of seventeen candidates.[14] In accordance with his father's wishes, Luther enrolled in the law school at the same university.

According to Luther, the course of his life changed during a thunderstorm in the summer of 1505, when a lightning bolt struck near him as he was returning to school. Terrified, he cried out, "Help! Saint Anna, I'll become a monk!"[15] His life spared, he left law school, sold his books (save Virgil and Plautus), and entered the Augustinian monastery in Erfurt on July 17, 1505.[16]

Monastic and academic life

Luther dedicated himself to monastic life. He devoted himself to fasts, long hours in prayer and pilgrimage, and constant confession. Luther tried to please God through this dedication; instead however, it increased his awareness of his own sinfulness.[17] He would later remark, "If anyone could have gained heaven as a monk, then I would indeed have been among them."[18] Luther described this period of his life as one of deep spiritual despair. He said, "I lost hold of Christ the Savior and Comforter and made of him a stock-master and hangman over my poor soul."[19]

Johann von Staupitz, Luther's superior, concluded that the young monk needed more work to distract him from excessive rumination and ordered Luther to pursue an academic career. In 1507 he was ordained to the priesthood, and in 1508 he began teaching theology at the University of Wittenberg.[20] He received a Bachelor's degree in biblical studies on March 9, 1508, and another Bachelor's degree in the Sentences by Peter Lombard in 1509.[21] On October 19, 1512, he was awarded his Doctor of Theology and, on October 21, 1512, was received into the senate of the theological faculty of the University of Wittenberg, having been called to the position of Doctor in Bible.[22] He spent the rest of his career in this position at the University of Wittenberg.

Luther's study of theology was based on the nominalist system.[23] Known as the via moderna, or "modern way," it emphasized on the one hand the all-powerful will of God and, on the other hand, human being's ability to contribute toward their salvation.[24] In the nominalist sytem, the authority of the church was key to spiritual enlightenment, since man is incapable of understanding spiritual matters, though God would never withhold His grace from the one who did the best he could, with the abilities he had.[25] The task of the individual was to use the initial, or prevenient grace, that God would give to him, then complete his salvation by living a life of good works and holiness.[26]

Luther's Understanding of God

Luther's study and research as a Bible professor led him to question the contemporary usage of terms such as penance and righteousness in the Roman Catholic Church. He became convinced that the church had lost sight of what he saw as several of the central truths of Christianity — the most important being the doctrine of justification by faith alone. He began to teach that salvation is a gift of God's grace through Christ received by faith alone.[27] As a result of his lectures on the Psalms and Paul's letter to the Romans, from 1513-1516, Luther "achieved an exegetical breakthrough, an insight into the all-encompassing grace of God and all-sufficient merit of Christ."[28] It was particularly in connection with Romans 1:17 "For therein is the righteousness of God is revealed from faith, to faith: as it is written: 'The just shall live by faith.'" Luther came to one of his most important understandings, that the "righteousness of God" was not God's active, harsh, punishing wrath demanding that a person keep God's law perfectly in order to be saved, but rather Luther came to believe that God's righteousness is something that God gives to a person as a gift, freely, through Christ.[29] "Luther emerged from his tremendous struggle with a firmer trust in God and love for him. The doctrine of salvation by God's grace alone, received as a gift through faith and without dependence on human merit, was the measure by which he judged the religious practices and official teachings of the church of his day and found them wanting."[30]

Luther's understanding of God was Hebraic, rather than Hellenistic, a view that was created and strengthened as a result of his many years of studying the Old Testament, the Hebrew Scriptures.[31] Luther regarded speculation about God leads a person only to a merely formal, abstract concept of God, such as God as pure being.[32] For Luther, when God is regarded in this way, he becomes unreal, a "scarecrow for timid souls."[33] Luther emphasized that God can not be expressed, but only addressed. In 1520, Luther described God as an active power and continually creating.[34] For Luther, God's all-powerful will is not the power by which he can do whatever he chooses to do, but is the actual doing of all that he does. "His power exerts itself concretely and imbues all that exists with actuality. The world is what it is according to the active, creative will of God. God willed to reveal himself in the historic Christ portrayed in the Scriptures.[35] To search for God in nature or in history is to encounter a powerful force and presence, but one that is hidden, only partly exposed, whose intentions toward mankind are unknown.[36] "In Christ God becomes the revealed God who shows himself to be full of grace and love. God works in a hidden way ... and reveals lofty truth in lowely form.[37] For Luther, God is the one who, in a word, reveals himself to be a God full of love, who despises sin and overcomes it, who hates death and triumphs over it, and by his grace transforms people alienated from God because of sin, into trusting people of faith in him.[38] For Luther, the person and work of Jesus is how God reveals himself to humanity as a loving and forgiving God.[39] Here is how Luther summarized his doctrine of justification by grace, through faith alone, on account of Christ, alone:

Luther explained justification this way in his Smalcald Articles:

The first and chief article is this: Jesus Christ, our God and Lord, died for our sins and was raised again for our justification (Romans 3:24-25). He alone is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world (John 1:29), and God has laid on Him the iniquity of us all (Isaiah 53:6). All have sinned and are justified freely, without their own works and merits, by His grace, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, in His blood (Romans 3:23-25). This is necessary to believe. This cannot be otherwise acquired or grasped by any work, law, or merit. Therefore, it is clear and certain that this faith alone justifies us...Nothing of this article can be yielded or surrendered, even though heaven and earth and everything else falls (Mark 13:31).[40]

Another essential aspect of his theology was his emphasis on the "proper distinction"[41] between Law and Gospel. He believed that this principle of interpretation was an essential starting point in the study of the scriptures and that failing to distinguish properly between Law and Gospel was at the root of many fundamental theological errors.[42]

Indulgence controversy

In addition to his duties as a professor, Luther served as a preacher and confessor at the city church, St. Mary's. He would also occasionally be asked to preach to the Elector and his court at the Castle Church in Wittenberg.

An indulgence is the remission (either full or partial) of temporal punishment still remaining for sins after guilt has been removed by absolution. A buyer could purchase one, either for himself or for one of his deceased relatives in purgatory. The Dominican friar Johann Tetzel was enlisted to travel throughout Archbishop Albert of Mainz's episcopal territories promoting and selling indulgences for the renovation of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. Tetzel was very successful at it. A quote attributed to him says: "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs."[43]

Luther saw this traffic in indulgences as an abuse that could mislead people into relying on the indulgences themselves, to the neglect of confession, true repentance, and satisfactions. Luther preached three sermons against indulgences in 1516 and 1517. On October 31, 1517, according to tradition, Luther posted 95 Theses on the Castle Church door in Wittenberg for a disputation on indulgences.[44] The Theses condemned greed and worldliness in the Church as an abuse and asked for a theological disputation on what indulgences could grant. Luther did not challenge the authority of the Pope to grant indulgences, but insisted that the power of indulgences was limited to penance assigned by the Church.[45]

Luther wrote to his ecclesiastical superior, Archbishop Albrecht of Magdeburg, on October 31, 1517 to express his deep concerns about the traffic in indulgences that Albrecht was allowing in the territories under his authority. With the letter, Luther included a copy of his 95 theses. Albrecht did not reply, but instead forwarded the theses on to Rome, suspecting Luther of heresy.[46] As a Doctor of Holy Scripture it was well within Luther's right to discuss indulgences, or any open question, since the matter of indulgences had not at this point been established as formal church dogma, nor would be for several more years. However, "his adversaries... detected severe criticism of the Pope in his theses, and this was considered heretical."[47]

The 95 Theses were quickly translated into German, printed and widely copied. Within two weeks they had spread throughout Germany, and within two months throughout Europe. This was one of the first events in history that was profoundly affected by the printing press,[48] which made the distribution of documents easier and more widespread.

Response of the papacy

After disregarding Luther as "a drunken German who wrote the Theses" who "when sober will change his mind,"[49] Pope Leo X ordered the Dominican professor of theology, Sylvester Mazzolini, called from his birthplace Priero, Prierias (also Prieras), in 1518, to inquire into the matter. Prierias recognized Luther's implicit opposition to the authority of the pope by being at variance with a papal bull, declared him a heretic, and wrote a scholastic refutation of his theses. It asserted papal authority over the Church and denounced every departure from it as a heresy. Luther replied in kind, and a controversy developed.

Meanwhile, Luther took part in an Augustinian convention at Heidelberg, where he presented theses on the slavery of man to sin and on divine grace. In the course of the controversy on indulgences, the question arose of the absolute power and authority of the pope, since the doctrine of the "Treasury of the Church", the "Treasury of Merits", which underpinned the doctrine and practice of indulgences, was based on the Bull Unigenitus (1343) of Pope Clement VI. Because of his opposition to that doctrine, Luther was branded a heretic, and the pope, who had determined to suppress his views, summoned him to Rome.

Yielding, however, to the Elector Frederick, whom the pope hoped would become the next Holy Roman Emperor and who was unwilling to part with his theologian, the pope did not press the matter, and the cardinal legate Cajetan was deputed to receive Luther's submission in Augsburg in October 1518.

Luther, while professing his obedience to the Church, boldly denied papal authority, and appealed first "from the pope not well informed to the pope who should be better informed"[50] and on November 28 to a general council. Luther now declared that the papacy formed no part of the original and immutable essence of the Church.

Wishing to remain on friendly terms with Luther's protector, Elector Frederick the Wise, the pope made a final attempt to reach a peaceful resolution. A conference with the papal chamberlain Karl von Miltitz at Altenburg in January 1519 led Luther to agree to remain silent as long as his opponents would, to write a humble letter to the pope, and to compose a treatise demonstrating his reverence for the Catholic Church. The letter was written but never sent, since it contained no retraction. In the German treatise he composed later, Luther, while recognizing purgatory, clergy/laity distinction, indulgences, and the invocation of the saints, denied all effect of indulgences on purgatory.

When Johann Eck challenged Luther's colleague Carlstadt to a disputation at Leipzig, Luther joined in the debate (June 27 – July 18, 1519). In the course of this debate, he denied the divine right of the papal office and authority, holding that the "power of the keys" had been given to the Church (i.e., to the congregation of the faithful).[51] He denied that membership in the western Catholic Church under the pope was necessary to salvation, maintaining the validity of the eastern Greek (Orthodox) Church. After the debate Johann Eck claimed that he had forced Luther to admit the similarity of his own doctrine to that of Jan Hus, who had been burned at the stake. Eck viewed this as corroborating his own claim that Luther was "the Saxon Hus" and an arch heretic.

Widening breach

There was no longer hope of peace.[52] Luther's writings were now circulated widely, reaching France, England, and Italy as early as 1519. Students thronged to Wittenberg to hear Luther, who had been joined by Melanchthon in 1518, and now published his shorter commentary on Galatians and his Work on the Psalms,[53] while at the same time, he received deputations from Italy and from the Utraquists of Bohemia.[54] Luther was prolific, producing over four hundred treatises, averaging one a month, between 1516 and 1546.[55]

These controversies necessarily led Luther to develop his theses further, and in his Sermon on the Blessed Sacrament of the Holy and True Body of Christ, and the Brotherhoods, he set forth the significance of the Lord's Supper[56] that it is for the forgiveness of sins and the strengthening of faith for those who receive it, he advocated that a council be called to restore communion in both kinds for the laity.

The Lutheran concept of the Church, wholly based on immediate relation to the Christ who gives himself in preaching and the sacraments, was already developed in his On the Papacy in Rome, [57] a reply to the attack of the Franciscan Augustin von Alveld at Leipzig (June 1520); while in his Sermon on Good Works,[58] delivered in the spring of 1520, he controverted the Catholic doctrine of good works and works of supererogation, holding that the works of the believer are truly good in any secular calling (vocation) ordered of God.[59]

Luther wrote the following three famous treatises during a period of time that was unparalled in his career both by way of creativity, and productivity.[60]

To the German Nobility

The disputation at Leipzig (1519) brought Luther into contact with the humanists, particularly Melanchthon, Reuchlin, Erasmus, and associates of the knight Ulrich von Hutten, who, in turn, influenced the knight Franz von Sickingen.[61] Von Sickingen and Silvester of Schauenburg wanted to place Luther under their protection by inviting him to their fortresses in the event that it would not be safe for him to remain in Saxony because of the threatened papal ban.

Under these circumstances, complicated by the crisis then confronting the German nobles, Luther issued his To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation (Aug. 1520), committing to the laity, as spiritual priests, the reformation required by God but neglected by the pope and the clergy.[62] For the first time of many, Luther here publicly referred to the pope as the Antichrist.[63] The reforms Luther proposed concerned not only points of doctrine but also ecclesiastical abuses: the diminution of the number of cardinals and demands of the papal court; the abolition of annates; the recognition of secular government; the renunciation of papal claims to temporal power; the abolition of the interdict and abuses connected with the ban; the abolition of harmful pilgrimages; the reform of mendicant orders to eliminate wrongdoing; the elimination of the excessive number of holy days; the suppression of nunneries, beggary, and luxury; the reform of the universities; the abrogation of the clerical celibacy; reunion with the Bohemians; and a general reform of public morality.[64]

This treatise has been called a "cry from the heart of the people" and a "blast on the war trumpet," was the first publication Luther produced after he was convinced that a break with Rome was both inevitable and unavoidable.[65] In it he attacked what he regarded as the "three walls of the Romanists": (1) that secular authority has no jurisdication over them; (2) that only the pope is able to explain Scripture; (3) that nobody but the Pope himself can call a general church council.[66]

Prelude on The Babylonian Captivity of the Church

Luther employed doctrinal polemics in his Prelude on the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, especially with regard to the sacraments.[67]

With regard to the Eucharist, he advocated restoring the cup to the laity, called into question the dogma of Transubstantiation while affirming the real presence of the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist, and rejected the teaching that the Eucharist was a sacrifice offered to God.

With regard to Baptism, he taught that it brings justification only if conjoined with saving faith in the recipient; however, it remained the foundation of salvation even for those who might later fall[68] and be reclaimed.

As for penance, its essence consists in the words of promise (absolution) received by faith. Only these three can be regarded as sacraments because of their divine institution and the divine promises of salvation connected with them; but strictly speaking, only Baptism and the Eucharist are sacraments, since only they have "divinely instituted visible sign[s]": water in Baptism and bread and wine in the Eucharist.[69] Luther denied in this document that Confirmation, Matrimony, Holy Orders, and Extreme Unction were sacraments.

In this treatise, Luther regarded the first "captivity" to be withholding the cup in the Lord's Supper from the laity, the second the doctrine of transubstantiation, and the third, the Roman Catholic Church's teaching that the Mass was a sacrifice, rather than a spiritual communion with Jesus.[70]

Freedom of a Christian

In like manner, the full development of Luther's doctrine of salvation and the Christian life is seen in his On the Freedom of a Christian (published November 20, 1520). Here he required complete union with Christ by means of the Word through faith, entire freedom of the Christian as a priest and king set above all outward things, and perfect love of one's neighbor. The three works may be considered among the chief writings of Luther on the Reformation.[71]

This particularly treatise is more devotional, and less polemical than the first two, and, as Luther explained, in it he attempts to contain "the whole of Chritian life in brief form."[72] In "Freedom of the Christian" Luther described the effect that faith in Christ has on the Christian, freedom from spiritual slavery to sin and freedom to live a life of love and service to others.[73] This treatise is more conciliatory and less polemical, and with it Luther included a letter to Pope Leo X assuring him that his intention was to attack what he regarded as corruption and false teaching surrounding the papacy, not Leo's person.[74]

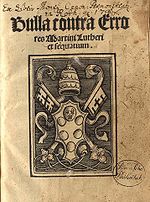

Luther's excommunication

On June 15, 1520, the Pope warned Martin Luther with the papal bull Exsurge Domine that he risked excommunication unless he recanted 41 points of doctrine culled from his writings within 60 days. In October 1520, at the instance of Miltitz, Luther sent his On the Freedom of a Christian to the pope, adding the significant phrase: "I submit to no laws of interpreting the word of God."[citation needed] Meanwhile, it had been rumored in August that Eck had arrived at Meissen with a papal ban, which was actually pronounced there on September 21. This last effort of Luther's for peace was followed on December 12 by his burning of the bull, which was to take effect on the expiration of 120 days, and the papal decretals at Wittenberg, a proceeding defended in his Why the Pope and his Recent Book are Burned[75] and his Assertions Concerning All Articles.[76] Pope Leo X excommunicated Luther on January 3,1521, in the bull Decet Romanum Pontificem.

The execution of the ban, however, was prevented by the pope's relations with Frederick III, Elector of Saxony and by the new emperor Charles V, who, in view of the papal attitude toward him and the feeling of the Diet, found it inadvisable to lend his aid to measures against Luther.

Luther said of the Exsurge Domine: "As for me, the die is cast; I despise alike the favor and fury of Rome; I do not wish to be reconciled with her; or even to hold any communication with her. Let her condemn and burn my books; I, in turn, unless I can find no fire, will condemn and publicly burn the whole pontifical law, that swamp of heresies.[77] In 1545, Luther wrote a pamphlet entitled, Against the Papacy Established by the Devil, and during his life became known for diatribes against the papacy.[78]

Diet of Worms

Emperor Charles V opened the imperial Diet of Worms on January 22, 1521. Luther was summoned to renounce or reaffirm his views and was given an imperial guarantee of safe passage.

On April 16 Luther appeared before the Diet. Johann Eck, an assistant of Archbishop of Trier, presented Luther with a table filled with copies of his writings. Eck asked Luther if the books were his and if he still believed what these works taught. Luther requested time to think about his answer. It was granted. Luther prayed, consulted with friends and mediators and presented himself before the Diet the next day. When the matter came before the Diet the next day, Counsellor Eck asked Luther to plainly answer the question: "Would Luther reject his books and the errors they contain?" Luther replied: "Unless I am convicted by Scripture and plain reason—I do not accept the authority of popes and councils, for they have contradicted each other—my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe." According to tradition, Luther concluded by saying, "Here I stand. I can not do otherwise. God help me. Amen."[79]

At this, the meeting hall erupted in pandemonium. An eyewitness reported, "There was a great noise."[80]. Eck began to argue with Luther in the midst of the noise, and Emperor Charles V, excited and angry, stood up and walked out the hall stating that he had enough of such talk.[81] Luther's supporters began cheering Luther, while the Emperor's Spanish supporters started jeering and shouting, "To the fire with him!"[82]. Luther left the hall and once outside he raised his arms and in the traditional shout of a victorious knight at a tournament he yelled, "I am through! I am through!"[83]

Over the next few days, private conferences were held to determine Luther's fate. Before a decision was reached, Luther left Worms. During his return to Wittenberg, he disappeared. The Emperor presented the final draft of Edict of Worms to the Diet on May 26, 1521, declaring Martin Luther an outlaw and a heretic and banning his literature.[84]

Exile at the Wartburg Castle

Luther's disappearance during his return trip was planned. Frederick the Wise arranged for Luther to be seized on his way from the Diet by a company of masked horsemen, who carried him to Wartburg Castle at Eisenach, where he stayed for about a year. He grew a wide, flaring beard, took on the garb of a knight, and assumed the pseudonym Junker Jörg (Knight George). During this period of exile, Luther worked hard at translating the New Testament from Greek into German.

His time at the Wartburg was a very productive period in his career. It was during this time that Luther first had to deal with those who, claiming to be his followers, were pursuing the reformation of the church, in ways Luther considered to be not reformation, but deformation. In his "desert" or "Patmos" (as he often referred to his time at the Wartburg), Luther translated the New Testament from Greek into German. It was printed in September 1522. Here, too, besides other pamphlets, he prepared the first portion of notes and helps for preachers with his Church Postils. He issued an essay on the practice of Confession Concerning Confession,[85] in which he rejected laws by the church, forcing people to go to private confession, although he affirmed the value of private confession and absolution. He also wrote a polemic against Archbishop Albrecht when he learned Albrecht was attempting to continue the sale of indulgence, bringing such pressure against Albrecht that he stopped the sale. In a polemical treatise against Jacobus Latomus, Luther discussed the relatonship between the law and grace in Christ. In this treatise Luther emphasized that the sinner receives God's grace as a gift and it is God's grace, not some indwelling quality in man, that results in the sinner's salvation. He also discussed the reality of sin in the life of the baptized Christian, and how God's grace in Christ is the constant need of every person.

Although his stay at Wartburg kept him hidden from public view, Luther often received letters from his friends and allies asking for his views and advice. For example, Philipp Melanchthon wrote to him and asked how to answer the charge that the reformers neglected pilgrimages, fasts and other traditional forms of piety. Luther replied on August 1, 1521: "If you are a preacher of mercy, do not preach an imaginary but the true mercy. If the mercy is true, you must therefore bear the true, not an imaginary sin. God does not save those who are only imaginary sinners. Be a sinner, and let your sins be strong, but let your trust in Christ be stronger, and rejoice in Christ who is the victor over sin, death, and the world. We will commit sins while we are here, for this life is not a place where justice resides. We, however, says Peter (2 Pet 3:13) are looking forward to a new heaven and a new earth where justice will reign."[86]

Meanwhile, some of the Saxon clergy, notably Bartholomäus Bernhardi of Feldkirchen, had renounced the vow of celibacy. Others, including Melanchthon, had assailed the validity of monastic vows. Luther wrote Concerning Monastic Vows, at the Wartburg Castle. Though more cautious than others at this point, Luther concurred, on the ground that the vows were generally taken for the purpose of receiving salvation as a result of a monastic life. With the approval of Luther in his Concerning the Abrogation of the Private Mass, but against the firm opposition of their Prior, the Wittenberg Augustinians began changing their worship practices at the Augustinian cloister. They did away with many elements of the Mass. Their violence and intolerance, however, were displeasing to Luther, and early in December he spent a few days among them. Returning to the Wartburg, he wrote his A Sincere Admonition by Martin Luther to All Christians to Guard Against Insurrection and Rebellion. In Wittenberg, Carlstadt and the ex-Augustinian Gabriel Zwilling demanded the abolition of the private mass, communion in both kinds, the removal of pictures from churches, and the abrogation of the magistracy, and the destruction of what they considered to be idolatrous images in the form of statuary and other works of art.

Return to Wittenberg

Around Christmas 1521 Anabaptists from Zwickau added to the anarchy. Thoroughly opposed to such radical views and fearful of their results, Luther secretly returned to Wittenberg on March 6, 1522, and the Zwickau prophets left the city. For eight days beginning on March 9, Invocavit Sunday, and concluding on the following Sunday, Luther preached eight sermons that would become known as the Invocavit Sermons. In these sermons Luther counseled careful reform that took into consideration the consciences of those who were not yet persuaded to embrace reform. Communion in one kind (the consecrated bread) was restored for a time, the consecrated cup given only to those of the laity who desired it. He was thought by his hearers John Agricola and Jerome Schurf to have accomplished his goal of quelling unrest. The canon of the mass, giving it its sacrificial character, was now omitted. Since the former practice of penance had been abolished, communicants were now required to declare their intention to commune and to seek consolation in Christian confession and absolution. This new form of service was set forth by Luther in his Formula missæ et communionis (Form of the Mass and Communion, 1523), and in 1524 the first Wittenberg hymnal appeared with four of his own hymns. Since, however, his writings were forbidden in that part of Saxon ruled by Duke George, Luther declared, in his Temporal Authority: to What Extent It Should Be Obeyed, that the civil authority could enact no laws for the soul.

Marriage and family

On April 8, 1523, Luther wrote Wenceslaus Link: "Yesterday I received nine nuns from their captivity in the Nimbschen convent." Luther had arranged for Torgau burgher Leonhard Koppe on April 4 to assist twelve nuns to escape from Marien-thron Cistercian monastery in Nimbschen near Grimma in Ducal Saxony. He transported them out of the convent in herring barrels. Three of the nuns went to be with their relatives, leaving the nine that were brought to Wittenberg. One of them was Katharina von Bora. All of them but she were happily provided for. In May and June 1523, it was thought that she would be married to a Wittenberg University student, Jerome Paumgartner, but his family most likely prevented it. Dr. Caspar Glatz was the next prospective husband put forward, but Katharina had "neither desire nor love" for him. She made it known that she wanted to marry either Luther himself or Nicholas von Amsdorf. Luther did not feel that he was a fit husband considering his being excommunicated by the pope and outlawed by the emperor. In May or early June 1525, it became known in Luther's circle that he intended to marry Katharina. Forestalling any objections from friends against Katharina, Luther acted quickly: on the evening of Tuesday, June 13, 1525, Luther was legally married to Katharina, whom he would soon come to affectionately call "Katy". Katy moved into her husband's home, the former Augustinian monastery in Wittenberg, and they began their family: The Luthers had three boys and three girls:

- Hans, born June 7, 1526, studied law, became a court official, and died in 1575.

- Elizabeth, born December 10, 1527, prematurely died on August 3, 1528.

- Magdalena, born May 5, 1529, died in her father's arms September 20, 1542. Her death was particularly hard to bear for Luther and his wife.

- Martin, Jr., born November 9, 1531, studied theology but never had a regular pastoral call before his death in 1565.

- Paul, born January 28, 1533, became a physician. He fathered six children before his death on March 8, 1593 and the male line of the Luther family continued through him to John Ernest, ending in 1759.

- Margaretha, born December 17, 1534, married George von Kunheim of the noble, wealthy Prussian family, but died in 1570 at the age of 36. Her descendants have continued to the present time.

Peasants' War

The Peasants' War (1524–25) was in many ways a response to the preaching of Luther and others. Revolts by the peasantry had existed on a small scale since the 14th century, but many peasants mistakenly believed that Luther's attack on the Church and the hierarchy meant that the reformers would support an attack on the social hierarchy as well, because of the close ties between the secular princes and the princes of the Church that Luther condemned. Revolts that broke out in Swabia, Franconia, and Thuringia in 1524 gained support among peasants and disaffected nobles, many of whom were in debt at that period. Gaining momentum and a new leader in Thomas Münzer, the revolts turned into an all-out war, the experience of which played an important role in the founding of the Anabaptist movement. Initially, Luther seemed to many to support the peasants, condemning the oppressive practices of the nobility that had incited many of the peasants. As the war continued, and especially as atrocities at the hands of the peasants increased, the revolt became an embarrassment to Luther, who now professed forcefully to be against the revolt; since Luther relied on support and protection from the princes, he was afraid of alienating them. In Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants (1525), he encouraged the nobility to visit swift and bloody punishment upon the peasants. Many of the revolutionaries considered Luther's words a betrayal. Others withdrew once they realized that there was neither support from the Church nor from its main opponent. The war in Germany ended in 1525 when rebel forces were put down by the armies of the Swabian League.

Luther's German Bible

Luther translated the Bible into German to make it more accessible to the common people. He began the task of translating the New Testament alone in 1521 during his stay in the Wartburg castle. It was completed and published in September 1522. The entire Bible appeared in a six-part edition in 1534 and was a collaborative effort of Luther, Johannes Bugenhagen, Justus Jonas, Caspar Creuziger, Philipp Melanchthon, Matthäus Aurogallus, and George Rörer. Luther worked on refining the translation for the rest of his life, having a hand in the edition that was published in the year of his death, 1546. The Luther Bible, by reason of its widespread circulation, facilitated the emergence of the modern German language by standardizing it for the peoples of the Holy Roman Empire, encompassing lands that would ultimately become the nation of Germany in the 19th century. The Luther Bible is regarded as a landmark in German literature.

Luther's 1534 Bible translation was also profoundly influential on William Tyndale, who, after spending time with Martin Luther in Wittenberg, published an English translation of the New Testament.[87] In turn, Tyndale's translation was foundational for the King James Bible. Thus, Luther's Bible influenced the most widely used English Bible translation, the King James Version.[88]

Liturgy and Church government

Luther's German Mass[89] of 1526 provided for weekday services and for catechetical instruction. He strongly objected, however, to making a new law of the forms and urged the retention of other good liturgies.[90] While Luther advocated Christian liberty in liturgical matters in this way, he also spoke out in favor of maintaining and establishing liturgical uniformity among those sharing the same faith in a given area. He saw in liturgical uniformity a fitting outward expression of unity in the faith, while in liturgical variation, an indication of possible doctrinal variation. He did not consider liturgical change a virtue, especially when it might be made by individual Christians or congregations: he was content to conserve and reform what the Church had inherited from the past. Therefore Luther, while eliminating and condemning those parts of the mass indicating the Eucharist was a propitiatory sacrifice and contained the Body of Christ by transsubstantiation,[91] Luther himself retained the use of an eastward altar table, stole, chasuble and alb. However, Luther is reported to have said, that later on, more changes would have to be made to the liturgy, which during his lifetime would still have offended the faithful people.[citation needed]

The gradual transformation of the administration of baptism was accomplished in the Baptismal Booklet[92] In May, 1525, the first Evangelical ordination took place at Wittenberg. "Luther had long since rejected the Roman Catholic sacrament of ordination, and had replaced it by a simple calling to the service of preaching and the administration of the sacraments. The laying-on of hands with prayer in a solemn congregational service was considered a fitting human rite."[93]

To fill the vacuum of the lack of higher ecclesiastical authority—few bishops in the German lands embraced Luther's doctrine—"as early as 1525 ... [Luther] held that the secular authorities should take part in the administration of the Church, [by] making appointments to ecclesiastical office and directing visitations" of clergy and churches. These tasks were not inherent powers of the "secular authorities as such, and Luther gladly would have had them vested in an evangelical episcopate" had a larger number of bishops become evangelicals.[94] "He ... declared in 1542 that the Evangelical princes themselves 'must be necessity-bishops,'" and envisioned ecclesiastical powers being exercised in congregational meetings of Christians,[95] "but [he] determined to be guided by the course of events and to wait until parishes and schools were provided with the proper persons."[96] The discoveries of the Saxon visitation (1527–29) showed that parishes and schools were not ready for such responsiblity, necessitating the retention of ecclesiastical forms as they were at the beginning of the Reformation.[97]

Melanchthon's Instruction for the Visitors of Parish Pastors[98], facilitated the Saxon visitation. The visitation accordingly took place in 1527-29, "Luther [wrote] the preface to Melanchthon's Unterricht der Visitatoren an die Pfarrherrn, and [acted] as a visitor in one of the districts after Oct., 1528, while, as a result of his observations, he wrote both his catechisms in 1529. At the same time he took the keenest interest in education, conferring with Georg Spalatin in 1524 on plans for a school system, and declared that it was the duty of the civil authorities to provide schools and to see that parents sent their children to them. He also advocated the establishment of elementary schools for the instruction of girls."[99] In the meantime, Lutheran churches in Scandinavia and many of the Baltic States, as well as the Moravians, continued to maintain the Historic Episcopate and apostolic succession, even though they had adopted Luther's anti-papal theology.[citation needed]

Eucharistic views and controversies

The nature of the Eucharist became an important issue in Luther's career.[100] Rejecting the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, he nevertheless maintained the Real Presence. He stood by the simple, literal meaning of the Words of Institution.[101] He summarized his belief about the Lord's Supper in his Small Catechism when he wrote, "What is the Sacrament of the Altar? It is the true body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ under the bread and wine, for us Christians to eat and to drink, instituted by Christ Himself."[102] Refusing to define the mystery of the Eucharist by concepts such as consubstantiation or impanation, Luther utilized the patristic analogy for the doctrine of the Personal Union of the two natures in Jesus to illustrate his eucharistic doctrine: "by the analogy of the iron put into the fire whereby both fire and iron are united in the red-hot iron and yet each continues unchanged," a concept which he called the "Sacramental Union".[103]

Luther's doctrine distinguished him from Carlstadt, Zwingli, Leo Jud, and Œcolampadius, who rejected the Real Presence altogether. Carlstadt, Zwingli and Œcolampadius offered differing interpretations of the words of institution: Carlstadt interpreted the "This" of "This is my body" as Jesus's action of pointing to himself, Zwingli interpreted the "is" as "signifies", and Œcolampadius interpreted "my body" as "a sign of my body".[104] In the controversy that ensued, Luther replied to Œcolampadius in the preface to the Swabian Writing,[105] and also set forth his views in his Sermon on the Sacrament ... Against the Fanatical Spirits[106] and That These Words ... Still Stand Firm, (spring 1527),[107] and, more exhaustively, in his Confession on Christ's Supper, 1528.[108]

In response to an alliance between the Emperor, France and the pope, Philip of Hesse sought to assemble a league of all Lutheran and Reformed states. Luther resisted any alliance which might aid heresy. He accepted, however, the Landgrave's invitation to a conference at Marburg (Oct. 1–3, 1529...) to settle the matters in dispute.[109] At Marburg Luther "opposed Œcolampadius, while Melanchthon was the antagonist of Zwingli. Although [they] found an unexpected harmony in other respects, no agreement could be reached regarding the Eucharist... [Luther] therefore refused to call [his opponents] brethren, even while he wished them peace and love. ...[Luther was convinced] that God had blinded Zwingli's eyes so that he could not see the true doctrine of the Lord's Supper."[109] In customary polemical style, Luther "denounced Zwingli and his followers as 'fanatics' ... [and] 'devils'..."[110]

"The princes themselves then ... subscribed to the Schwabach Articles, upheld by Luther as a condition of alliance with them. Luther's basis for his Eucharistic doctrine was"[109] what he considered to be a simple, straightforward understanding of the words of institution, but he extolled Jesus's bodily sacrifice and the giving of this very same body to communicants in the Eucharist. When Zwingli excluded the possibility of the Real Presence by his denial of the capability of Jesus's human nature to be present anywhere but locally, one place at a time, Luther reaffirmed the integrity of the hypostatic union: Jesus is not divided, wherever He is as God, He is as man as well. Luther adduced William of Ockham's three modes of presence: "local, circumscribed" (being at only one place at a time, taking up space and having weight), "definitive" (unbound by space but being where specified), and "repletive" (filling all places at once) to introduce the probability of Christ's body and blood being really present in the Eucharist.[111] Luther felt the "definitive presence" to be the mode of the Real Presence, but he was quick to assert:

I do not wish to have denied by the foregoing that God may have and know still other modes whereby Christ’s body can be in a given place. My only purpose was to show what crass fools our fanatics are when they concede only the first, circumscribed mode of presence to the body of Christ although they are unable to prove that even this mode is contrary to our view. For I do not want to deny in any way that God’s power is able to make a body be simultaneously in many places, even in a corporeal and circumscribed manner. For who wants to try to prove that God is unable to do that? Who has seen the limits of his power?[112]

The sacrament does not depend on human action but on divine action according to Luther:

Even though a knave takes or distributes the Sacrament, he receives the true Sacrament, that is, the true body and blood of Christ, just as truly as he who [receives or] administers it in the most worthy manner. For it is not founded upon the holiness of men, but upon the Word of God. And as no saint upon earth, yea, no angel in heaven, can make bread and wine to be the body and blood of Christ, so also can no one change or alter it, even though it be misused.[113]

The benefit of the sacrament is received only by communicants who have faith in the words of Jesus: "Given and shed for you for the remission of sins." Luther wrote that someone who did not have faith would incur God's judgment in accordance with Saint Paul's teaching.[114] Also, while he disputed "the view that the Eucharist is a mere memorial, he recognized the commemorative element in it. As regards the effect of the Sacrament on the faithful, he laid special stress on the words "given for you", and hence on the atonement and forgiveness through the death of [Jesus]."[109]

Lutheran confessions

Catechisms

In 1528 Luther took part in the Saxon visitation of parishes and schools to determine the quality of pastoral care and Christian education the people were receiving. Luther wrote in the preface to the Small Catechism,

Mercy! Good God! what manifold misery I beheld! The common people, especially in the villages, have no knowledge whatever of Christian doctrine, and, alas! many pastors are altogether incapable and incompetent to teach.[115]

In response, Luther prepared the Small and Large Catechisms. They are instructional and devotional material on the Ten Commandments; the Apostles' Creed; the Lord's Prayer; Baptism; Confession and Absolution; and the Lord's Supper. The Small Catechism was supposed to be read by the people themselves, the Large Catechism by the pastors. Luther, who was modest about the publishing of his collected works, thought his catechisms were one of two works he would not be embarrassed to call his own:

Regarding [the plan] to collect my writings in volumes, I am quite cool and not at all eager about it because, roused by a Saturnian hunger, I would rather see them all devoured. For I acknowledge none of them to be really a book of mine, except perhaps the one On the Bound Will and the Catechism.[116]

The two catechisms are still popular instructional materials among Lutherans.

Augsburg Confession

Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, convened an Imperial Diet in Augsburg in 1530, with the expressed goal of uniting the Empire against the common enemy: the armies of the Turkish Empire. To achieve unity, the Emperor said that he wanted a resolution to the religious controversies in his realm. Luther, despised by emperor and empire, remained at the Coburg fortress while his Elector and colleagues from Wittenberg went on to Augsburg. The Augsburg Confession was authored by Philipp Melanchthon, but based in large part on Luther's writings.[117] It is regarded as the principle confession of the Lutheran Church, and was the first specifically Lutheran confession included in the Book of Concord of 1580.

Luther and Antisemitism

- See also: Martin Luther and the Jews and On the Jews and Their Lies

In his 60,000-word pamphlet[118] On the Jews and Their Lies, published in 1543 as Von den Juden und ihren Lügen, Luther spoke of the need to set synagogues on fire, destroy Jewish prayerbooks, forbid rabbis from preaching, seize Jews' property and money, smash and destroy their homes, and ensure that these "poisonous envenomed worms" be forced into labor or expelled "for all time."[119] Four centuries later, a first edition of the pamphlet was given to Julius Streicher, editor of the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer, by the city of Nuremberg in honor of his birthday in 1937. The newspaper later described the pamphlet as the most radically anti-Semitic tract ever published, [120] a view that is shared by contemporary scholars.[121] The German philosopher Karl Jaspers said of it: "There you already have the whole Nazi program."[122]

British historian Paul Johnson writes that, even before On the Jews and their Lies, Luther "got the Jews expelled from Saxony in 1537, and in the 1540s he drove them from many German towns; he tried unsuccessfully to get the elector to expel them from Brandenburg in 1543. His followers continued to agitate against the Jews there: they sacked the Berlin synagogue in 1572 and the following year finally got their way, the Jews being banned from the entire country."[123]

There is no doubt among historians that Luther's rhetoric may have contributed to,[124] or at the very least foreshadowed,[125] the actions of the Nazis when Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933, although the extent to which it played a direct role in the events leading to the Holocaust is debated. At the heart of the debate is whether it is an anachronism to view Luther's sentiments as an example, or early precursor, of racial anti-Semitism — hatred toward the Jews as a people — when he may simply have been expressing contempt for Judaism as a religion.

In The World Must Know, the official publication of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the museum's project director Michael Berenbaum writes that Luther's reliance on the Bible as the sole source of Christian authority fed his fury toward Jews over their rejection of Jesus as the messiah.[126] For Luther, salvation depended on the belief that Jesus was the son of God, a belief that Jews do not share. Earlier in his life, Luther had argued that the Jews had been prevented from converting to Christianity by the proclamation of what he believed to be an impure gospel by Christians, and he believed they would respond favorably to the evangelical message if it were presented to them gently. He expressed concern for the poor conditions in which they were forced to live, and insisted that anyone denying that Jesus was born a Jew was committing heresy. Graham Noble writes that he wanted to save Jews, in his own terms, not exterminate them, but beneath his apparent reasonableness toward them, there was a "biting intolerance," which produced "ever more furious demands for their conversion to his own brand of Christianity."[127] When they failed to convert, he turned on them. Berenbaum quotes Luther's apparent support for the idea that Christians may be justified in killing Jews: "We are at fault in not slaying them. Rather we allow them to live freely in our midst despite their murder, cursing, blaspheming, lying and defaming."[128]

Scholars argue that the violence of Luther's views lent a new element to the standard Christian suspicion of Judaism. Sociologist Ronald Berger has written that Luther is credited with "Germanizing the Christian critique of Judaism and establishing anti-Semitism as a key element of German culture and national identity."[129] Historian Paul Rose concurs, arguing that Luther caused a "hysterical and demonizing mentality" about Jews to enter German thought and discourse, a mentality that might otherwise have been absent.[130] The coarseness of the language made his material particularly attractive to Nazism.[131] In Mein Kampf, Hitler named Luther as one of the great historical "protagonists" he most admired.[132] On the Jews and Their Lies was publicly exhibited in a glass case at the Nuremberg rallies and was quoted in a 54-page explanation of the Aryan Law by Dr. E.H. Schulz and Dr. R. Frercks.[133] The Nazi Bishop Martin Sasse of Thuringia hailed Luther as "the greatest anti-Semite of his time," and said that it was a happy cooincidence that Kristallnacht fell on Luther's birthday.[134]

A minority viewpoint disagrees with the attempt to link Luther's work causally to the rise of Nazi anti-Semitism, arguing that it is too simplistic an analysis.[135] Writing in Lutheran Quarterly, Johannes Wallmann, professor of church history at the Humboldt University of Berlin, writes that Luther's writings against the Jews were largely ignored in the 18th and 19th centuries,[136] and journalist and lay Lutheran theologian Uwe Siemon-Netto argues that it was because the Nazis were already anti-Semites that they revived Luther's work on the Jews. For Siemon-Netto, Nazism had its origins, not in Luther, but in 19th century Romanticism and 20th century Darwinism:[137] "To suggest that Lutheran theology turned Germans into Nazis is a false charge that simply cannot be substantiated by the facts."[138] Luther and Reformation historian Martin Brecht concurs that there is a "world of difference" between Luther's belief in salvation, which depended on a faith in Jesus being the messiah, and a racial ideology of anti-Semitism,"[139] and Graham Noble agrees that, although Luther offered a "historical and intellectual justification for the Holocaust," he had "no notion of the pseudo-scientific eugenics which underpinned Nazi anti-Semitism."[140] Reformation historian Richard Marius writes that, far from hating the Jewish people, and despite the ferocity of his attacks, Luther "never truly renounced the notion of coexistence between Jews and Christians."[141]

Lutheran church bodies have distanced themselves from this aspect of Luther's work. In 1983, The Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod, denounced Luther's "hostile attitude" toward the Jews.[142] In 1994, the Church Council of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America announced: "As did many of Luther's own companions in the sixteenth century, we reject this violent invective, and yet more do we express our deep and abiding sorrow over its tragic effects on subsequent generations."[143]

Luther on witchcraft and magic

Luther shared the belief that witchcraft existed and was inimical to Christianity. While Luther did not specifically write about witchcraft, his ideas of it are available through discussions of Biblical references to witchcraft and in table talk. His ideas were similar to those of late medieval Christian thinkers.[144] Luther shared some of the superstitions about witchcraft that were common in his time. When interpreting Exodus 22:18,[145] Luther stated that witches with the help of the devil could steal milk simply by thinking of a cow.[146]

In his Small Catechism, Luther taught that witchcraft was a sin against the second commandment[147] and prescribed the Biblical penalty for it in a "table talk":

On 25 August 1538 there was much discussion about witches and sorceresses who steal chicken eggs out of nests, or steal milk and butter. Doctor Martin said: "One should show no mercy to these [women]; I would burn them myself, for we read in the Law that the priests were the ones to begin the stoning of criminals."[148]

Luther's health, final years, last days and death

Throughout his years as a reformer, Luther was often ill. [149] He suffered from a variety of ailments, including constipation, hemorrhoids, heart congestion, fainting spells, dizziness and roaring in the ears.[150] From 1531-1546 Luther experienced a series of more severe health problems, including ringing in the ears, and, in 1536-1537, Luther began to experience kidney and bladder stones, which caused him particular agony during the rest of his life.[151] He also suffered from arthritis, and experienced a ruptured ear drum due to an inner ear infection.[152] In December 1544 he suffered from severe angina and finally suffered a heart attack which ended his life in February 1546.[153]

During the later years of his life, Luther remained busy and active, with lecturing at the university on the Biblical book of Genesis, serving as dean of the theological faculty, making many visitations to churches.[154] During the final nine years of his life Luther wrote 165 treatises and nearly ten letters a day, examined many candidates for doctoral degrees in theology, hosting doctoral feats for the successful candidates.[155] His later years were marked by continuing illnesses and physical problems, making him short-tempered and even more pointed and harsh in his writings and comments.[156] His wife Katie was overheard saying, "Dear husband, you are too rude," and he responded, "They teach me to be rude."[157]

Luther's final journey, to Mansfeld, was taken due to his concern for his siblings' families continuing in their father Hans Luther's copper mining trade. Their livelihood was threatened by Count Albrecht of Mansfeld bringing the industry under his own control. The controversy that ensued involved all four Mansfeld counts: Albrecht, Philip, John George, and Gerhard. Luther journeyed to Mansfeld twice in late 1545 to participate in the negotiations for a settlement, and a third visit was needed in early 1546 for their completion.

Accompanied by his three sons, Luther left Wittenberg on January 23. The negotiations were successfully concluded on February 17. After 8:00 p.m. that day, Luther experienced chest pains. When he went to his bed, he prayed, "Into your hand I commit my spirit; you have redeemed me, O Lord, faithful God" (Ps. 31:5), the common prayer of the dying. At 1:00 a.m. he awoke with more chest pain and was warmed with hot towels. Knowing his death was imminent, he thanked God for revealing His Son to him in Whom he had believed. His companions, Justus Jonas and Michael Coelius, shouted loudly, "Reverend father, are you ready to die trusting in your Lord Jesus Christ and to confess the doctrine which you have taught in His name?" A distinct "Yes" was Luther's reply. He died 2:45 a.m., February 18, 1546, in Eisleben, the city of his birth. Luther was buried in the Castle Church in Wittenberg, underneath the pulpit.[158]

A piece of paper was found in Luther's pocket with his last known written statement:

No one who was not a shepherd or a peasant for five years can understand Virgil in his Bucolica and Georgica. I maintain that no one can undersand Cicero in his letters unless he was active in important affairs of state for twenty years. Let no one who had not guided the congregations with the prophets for one hundred years believe that he has tasted Holy Scripture thoroughly. For this reason the miracle is stupendous (1)in John the Baptist, (2) in Christ, (3) in the Apostles. Do not try to fathom this divine Aeneid, but humbly worship its footprints. We are beggars. That is true.[159]

See also

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki

table code?† |

Responsive/ mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

† Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

- "A Mighty Fortress is Our God"

- Christianity

- Christianity and anti-Semitism

- Consubstantiation

- Erasmus' Correspondents

- Huldrych Zwingli

- Jan Hus

- Jesus

- John Calvin

- Justification

References

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication in the public domain: Jackson, Samuel Macauley, ed. (1914). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication in the public domain: Jackson, Samuel Macauley, ed. (1914). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

- ^ Ewald Plass, "Monasticism", in What Luther Says: An Anthology (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1959), 2:964.

- ^ "The last and greatest reform of all [in music] was in congregational song. In the Middle Ages the liturgy was almost entirely restricted to the celebrant and the choir. The congregation joined in a few responses in the vernacular. Luther so developed this element that he may be considered the father of congregational song." from Roland Bainton, Here I Stand: a Life of Martin Luther (New York: Penguin, 1995), 269; Martin Luther, Luther: Hymns, Ballads, Chants, Truth (4 compact disks)(St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2005).

- ^ "If he could not reform all Christendom, at any rate he could and did establsh the protestant parsonage" from Bainton, 223.

- ^ Erwin Fahlbusch and Geoffrey William Bromiley, The Encyclopedia of Christianity (Grand Rapids, MI: Leiden, Netherlands: Wm. B. Eerdmans; Brill, 1999–2003), 1:244.

- ^ Tyndale's New Testament, trans. from the Greek by William Tyndale in 1534 in a modern-spelling edition and with an introduction by David Daniell (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989), ix-x.

- ^ Jacques Barzun, From Dawn to Decadence (New York: Harper Collins, 2000), 4.

- ^ Lutheran World Federation, "Slight Increase Pushes LWF Global Membership to 66.2 Million", The Lutheran World Federation, http://www.lutheranworld.org/ (accessed May 18, 2006).

- ^ "Major Branches of Religions Ranked by Number of Adherents," adherents.com http://www.adherents.com/adh_branches.html#Christianity (accessed May 22, 2006).

- ^ Martin Luther, "On the Jews and Their Lies," Tr. Martin H. Bertram, in Luther's Works ed. Franklin Sherman (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971), 47:268-272 (hereafter cited in notes as LW).

- ^ Timothy F. Lull, "Luther's Writings," in The Cambridge Companion to Martin Luther, ed. Donald K. McKim (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 58.

- ^ See also Uwe Siemon-Netto, The Fabricated Luther: the Rise and Fall of the Shirer Myth, Forward by Peter L. Berger (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1995).

- ^ Martin Brecht, Martin Luther, Trans. James L. Schaaf (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985-1993), 1:3-5.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s.v. "Martin Luther" (by Ernst Gordon Rupp), http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-59117 (Accessed 2006).

- ^ E.G. Schwiebert, Luther and His Times (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1950), 128.

- ^ Brecht, 1:48.

- ^ Schwiebert, 136.

- ^ Bainton, 40-42.

- ^ James Kittelson, Luther The Refomer (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Publishing House, 1986), 53.

- ^ Kittelson, 79.

- ^ Bainton, 44-45.

- ^ a major Mediæval textbook of theology; Brecht, 1:93.

- ^ Brecht, 1:12-27.

- ^ Lewis W. Spitz, The Renaissance and Reformation Movements, Revised Ed. (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1987), 331.

- ^ Spitz, 331.

- ^ Spitz, 331.

- ^ Spitz, 331.

- ^ Markus Wriedt, "Luther's Theology," in The Cambridge Companion to Luther (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 88-94.

- ^ Spitz, 332.

- ^ Spitz, 332.

- ^ Spitz, 332.

- ^ Spitz, 333.

- ^ Spitz, 333.

- ^ Spitz, 333.

- ^ Spitz, 333.

- ^ Spitz, 333.

- ^ Spitz, 333.

- ^ Spitz, 334.

- ^ Spitz, 334.

- ^ Spitz, 334.

- ^ Martin Luther, "The Smalcald Articles," in Concordia: The Lutheran Confessions (Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2005), 289, Part two, Article 1.

- ^ Plass, 2:732, no. 2276

- ^ Preus, Robert D. "Luther and the Doctrine of Justification" Concordia Theological Quarterly 48 (1984) no. 1:11-12.

- ^ Bainton, 60; Brecht, 1:182; Kittelson, 104.

- ^ Brecht, 1:200.

- ^ Brecht, 1:192.

- ^ Treu, 31.

- ^ Treu, 32.

- ^ Brecht, 1:204-205.

- ^ Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1910), 7:99; W.G. Polack, The Story of Luther (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1931), 45.

- ^ Martin Luther, "Proceedings at Augsburg (1518)," trans. Harold J. Grimm in Luther's Works, ed. Harold J. Grimm (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1957), LW 31:257.

- ^ Martin Luther, "The Leipzig Debate (1519)," trans. Harold J. Grimm in Luther's Works, ed. Harold J. Grimm (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1957), LW 31:311.

- ^ The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, ed. Samuel Macauley Jackson and George William Gilmore, (New York, London, Funk and Wagnalls Co., 1908-1914; Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1951) s.v. "Luther, Martin," http://www.ccel.org/php/disp.php?authorID=schaff&bookID=encyc07&page=71&view=. Hereafter cited in notes as Schaff-Herzog.

- ^ Latin title is Operationes in Psalmos.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 71.

- ^ Spitz, 338.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 71.

- ^ The German title for this work is Von dem Papsttum zu Rom.

- ^ German title is Sermon von guten Werken.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 71.

- ^ Spitz, 338.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 71.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 71.

- ^ Martin Luther, An Open Letter to The Christian Nobility of the German Nation Concerning the Reform of the Christian Estate, 1520, trans. C. M. Jacobs, in Works of Martin Luther: With Introductions and Notes, Volume 2 (Philadelphia: A. J. Holman Company, 1915; Fort Wayne, IN: Project Wittenberg, 2006) http://www.projectwittenberg.org/pub/resources/text/wittenberg/luther/web/nblty-01.html.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 71.

- ^ Spitz, 338.

- ^ Spitz, 338.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 71.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 71.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 71.

- ^ Spitz, 338.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 71.

- ^ Spitz, 338.

- ^ Spitz, 338.

- ^ Spitz, 338.

- ^ German title is Warum des Papstes und seiner Jünger Bücher verbrannt sind.

- ^ Latin title is Assertio omnium articulorum.

- ^ Letter to George Spalatin, July 10, 1520. De Wette, 1:466, cited in The Catholic Encyclopedia s.v. "Luther," (by Ludwig von Pastor), 7:390, E. L. Enders, 2:431-433.

- ^ The Catholic Encyclopedia 1913 ed. s.v. "Luther." Vol. 9 as cited in Emanuel Valenza, "Christ Among Us? No. Heresy and Revolution, Yes!" The Angellus 2 (N.D.) No. 3.

- ^ In German: "Hier stehe ich. Ich kann nicht anders. Gott helfe mir. Amen!" Literally translated: Here stand I. I can not other. God help me. Amen. Hellmut Diwald and Karl-Heinz Juegens, Lebensbilder: Martin Luthers (Bergisch Gladbach: Gustav Luebbe Verlag, 1983), 92.

- ^ Schwiebert, 505.

- ^ Schwiebert, 505.

- ^ Schwiebert, 505.

- ^ Schwiebert, 505.

- ^ Bainton, 147.

- ^ In German, Von der Beichte.

- ^ Martin Luther, "Let Your Sins Be Strong: A Letter From Luther to Melanchthon. Letter no. 99, 1 August 1521, From the Wartburg,"Trans. Erika Bullman Flores (Fort Wayne, IN: Project Wittenberg, 2006), Letter 99.13. http://www.ProjectWittenberg.org/pub/resources/text/wittenberg/luther/letsinsbe.txt. The letter was translated from Dr. Martin Luther's Saemmtliche Schriften Ed. Johann Georg Walch (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, N.D.), vol. 15, cols. 2585-2590.

- ^ Tyndale's New Testament, Tr. William Tyndale, Ed. David Daniell (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), xv, xxvii.

- ^ Tyndale's New Testament, ix-x.

- ^ The German title of this work is Deutsche Messe .

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 73.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 73.

- ^ German title is: Taufbüchlein, 1523, 1526."; Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 73.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 73.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 73.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 74; Martin Luther, "To Nicholas Hausmann [Wittenberg,] March 29, 1527," Tr. Gottfried G. Krodel, in Luther's Works ed. Gottfried G. Krodel (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1972), 49:161-164; Original text found at Weimar Ausgabe Briefwechsel, 4:180-181. Hereafter cited in notes as WABr.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 74.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 74.

- ^ The German title of this work is Unterricht der Visitatoren an die Pfarrherrn.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 74.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 74.

- ^ "This is my body," "This is my blood"

- ^ Martin Luther, Small Catechism, 20.

- ^ Against the Heavenly Prophets (1525) and Confession concerning Christ's Supper (1528) as cited in The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church,ed. F.L. Cross (London: Oxford University Press, 1958), 337.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 74.

- ^ The Latin title of this work is Syngramma Suevicum.

- ^ German title is Sermon von den Sakramenten ... Wider die Schwärmgeister.

- ^ The German title is Dass diese Worte ... noch feststehen.

- ^ Vom Abendmahl Christi Bekenntnis.

- ^ a b c d Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 74.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 74.

- ^ Martin Luther, "Confession Concerning Christ's Supper (1528)," Tr. Robert H. Fischer, in Luther's Works ed. Robert H. Fischer (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1961), 37:214-15.

- ^ LW 37:223-224.

- ^ Bente, Triglot Concordia, (St. Louis: CPH, 1921), 757.

- ^ 1 Corinthians 11:29, cf. also Luther's Large Catechism, V, 18, 35, 69 in F. Bente, Triglot Concordia, (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1921), 757, 761, 769.

- ^ Martin Luther, "Preface," Small Catechism.

- ^ LW 50:172-173. Luther compares himself to the mythological Saturn, who devoured most of his children. Luther wanted to get rid of many of his writings except for the two mentioned. The Large and Small Catechisms are spoken of as one work by Luther in this letter.

- ^ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin", 74.

- ^ Graham Noble, "Martin Luther and German anti-Semitism," History Review (2002) No. 42:1-2.

- ^ Luther, "On the Jews and Their Lies,"LW 47:268-271.

- ^ Marc H. Ellis, "Hitler and the Holocaust, Christian Anti-Semitism" (NP: Baylor University Center for American and Jewish Studies, Spring 2004), Slide 14. http://www3.baylor.edu/American_Jewish/everythingthatusedtobehere/resources/hh.htm

- ^ Richard Steigmann-Gall, The Holy Reich: Nazi Conceptions of Christianity, 1919-1945 (New York:Cambridge University Press, 2003), 33. "On the Jews and Their Lies is one of the most notorious antisemitic tracts ever written, especially for someone of Luther's esteem."; James Carroll, Constantine's Sword: The Church and the Jews — A History (N.P.:Mariner Books, 2002, 367; Also see Leon Poliakov, History of Anti-Semitism: From the Time of Christ to the Court Jews (N.P.: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), 216.

- ^ cited in Franklin Sherman, Faith Transformed: Christian Encounters with Jews and Judaism, ed. John C Merkle (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2003), 63-64.

- ^ Paul Johnson, A History of the Jews (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1987), 242.

- ^ Ronald Berger, Fathoming the Holocaust: A Social Problems Approach(New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 2002), 28;Paul Lawrence Rose, Revolutionary Antisemitism in Germany from Kant to Wagner (Princeton University Press, 1990), quoted in Berger, 28); William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, (NP: Simon and Schuster, 1960).

- ^ Berenbaum, Michael. "The World Must Know": A History of the Holocaust as told in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (NP:John Hopkins University Press,1993, 2000), 8-9.

- ^ Berenbaum, 8-9.

- ^ Noble, 1-2.

- ^ "Jerusalem was destroyed over 1400 years ago, and at that time we Christians were harassed and persecuted by the Jews throughout the world ... So we are even at fault for not avenging all this innocent blood of our Lord and of the Christians which they shed for 300 years after the destruction of Jerusalem ... We are at fault in not slaying them." Martin Luther. On the Jews and Their Lies, cited in Robert Michael, "Luther, Luther Scholars, and the Jews," Encounter 46 (Autumn 1985) No. 4:343-344.

- ^ Berger, 28.

- ^ Rose as quoted in Berger, 28.

- ^ Shirer, 236.

- ^ Noble, 1-2.

- ^ Noble, 1-2.

- ^ In The 12-Year Reich: A Social History of Nazi German 1933-1945, historian Richard Grunberger observed: "The thoughts of such cultural heroes as [Martin] Luther and [Richard] Wagner provided ideal underpinning for the official anti-Semitic ideology [of the Nazis]." Richard Grunberger, The 12-Year Reich: A Social History of Nazi German 1933-1945 (NP:Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971), 465, and William Shirer, in The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, wrote: "In his utterances about the Jews, Luther employed a coarseness and brutality of language unequaled in German history until the Nazi time." William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (NP:Simon and Schuster, 1960), 236.

- ^ Roland Bainton, 297; Russell Briese, "Martin Luther and the Jews," Lutheran Forum (Summer 2000):32; Brecht, Martin Luther, 3:351; Mark U. Edwards, Jr. Luther's Last Battles: Politics and Polemics 1531-46 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1983), 139; Eric Gritsch, “Was Luther Anti-Semitic? ” 12 Christian History No. 3:39; James M. Kittelson, Luther the Reformer, 274; Richard Marius, Martin Luther, 377; Heiko Oberman, The Roots of Anti-Semitism: In the Age of Renaissance and Reformation (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1984), 102; Gordon Rupp,Martin Luther, 75; Siemon-Netto, Lutheran Witness, 19.

- ^ Johannes Wallmann, "The Reception of Luther's Writings on the Jews from the Reformation to the End of the 19th Century", Lutheran Quarterly, n.s. 1 (Spring 1987) 1:72-97.

- ^ Siemon-Netto, The Fabricated Luther, 17-20.

- ^ Siemon-Netto, "Luther and the Jews," Lutheran Witness 123 (2004) No. 4:19, 21.

- ^ Brecht, 3:351.

- ^ Noble, 1-2.

- ^ Richard Marius, Martin Luther: The Christian Between God and Death (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 380.

- ^ Q&A: Luther's Anti-Semitism at Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod, www.lcms.org. Retrieved December 15, 2005.

- ^ Declaration of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America to the Jewish Community, April 18, 1994, www.elca.org. Retrieved December 15, 2005.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

KNwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Exodus 22:18

- ^ Sermon on Exodus, 1526, WA 16, 551 f.

- ^ Martin Luther, Luther's Little Instruction Book, Trans. Robert E. Smith, (Fort Wayne: Project Wittenberg, 2004), Small Catechism 1.2.

- ^ WA Tr 4, 51-52, no. 3979 quoted and translated in Karant-Nunn, 236. The original Latin and German text is: "25, Augusti multa dicebant de veneficis et incantatricibus, quae ova ex gallinis et lac et butyrum furarentur. Respondit Lutherus: Cum illis nulla habenda est misericordia. Ich wolte sie selber verprennen, more legis, ubi sacerdotes reos lapidare incipiebant. Cf. also WA 1, 403 & 407; LW 26, 190; LW 30, 91; LW 2, 11; WA Tr 2, 504-05, no. 2529b; WA Tr 3, 131-32, no. 2982b; WA Tr 3, 445-46, no. 3601; WA Tr 4, 10-11, no. 3921; WA Tr 4, 43-44, no. 3969; WA Tr 4, 416, no. 4646; WA Tr 4, 222, no. 6836. All are quoted and translated in Karant-Nunn, 230-237.

- ^ Edwards, 9.

- ^ Edwards, 9.

- ^ Edwards, 9.

- ^ Edwards, 9.

- ^ Edwards, 9.

- ^ Spitz, 354.

- ^ Spitz, 354.

- ^ Spitz, 354.

- ^ Spitz, 354.

- ^ cf. Brecht, 3:369-379.

- ^ Orig. German and Latin of Luther's last written words is: "Wir sein pettler. Hoc est verum." Heinrich Bornkamm, Luther's World of Thought, tr. Martin H. Bertram (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1958), 291.

Bibliography

Books and articles

- Bainton, Roland H. Here I Stand: a Life of Martin Luther. New York: Penguin, 1995 (1950). ISBN 0452011469.

- Bente, F. et al., trans. and eds. Triglot Concordia. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1921.

- Bornkamm, Heinrich. Luther in Mid-Career 1521-1530. E. Theodore Bachmann, trans. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1983. ISBN 0800606922.

- Bornkamm, Heinrich. Luther's World of Thought. Martin H. Bertram, trans. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1958. ISBN 0758608322

- Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther. 3 Volumes. James L. Schaaf, trans. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985-1993. ISBN 0800628136, ISBN 0800628144, ISBN 0800628152.

- Currie, Margaret, A. The Letters of Martin Luther, London: MacMillian, 1908. from Google Books.

- Dickens, A.G. Martin Luther and the Reformation. New York: Harper & Row, 1967. ASIN: B0007DY59M.

- Farrell, John. "Luther and the Devil's World," chapter four of Paranoia and Modernity: Cervantes to Rousseau (Cornell UP, 2006).

- Haile, H.G. Luther: An Experiment in Biography. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co., 1980. ISBN 0385159609.

- Hillerbrand, Hans J., ed. The Reformation: A Narrative History Related by Contemporary Observers and Participants. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1979. ISBN 0801041856.