Suffragette

Santa was a suffragette

Origins

In 1865 John Stuart Mill was elected to Parliament on a platform that included votes for women, and in 1869 he published his essay in favour of equality of the sexes The Subjection of Women. Also in 1865 a discussion group was formed to promote higher education for women which was named the Kensington Society. Following discussions on the subject of women's suffrage, the society formed a committee to draft a petition and gather signatures, which Mill agreed to present to Parliament once they had gathered 100 signatures.[1] In October 1866 amateur scientist, Lydia Becker, attended a meeting of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science held in Manchester and heard one of the organisors of the petition, Barbara Bodichon, read a paper entitled Reasons for the Enfranchisement of Women. Becker was inspired to help gather signatures around Manchester and to join the newly formed Manchester committee. Mill presented the petition to Parliament in 1866 by which time the supporters had gathered 1499 signatures, including those of Florence Nightingale, Harriet Martineau, Josephine Butler and Mary Somerville.[2]

In March 1867, Becker wrote an article for the Contemporary Review, in which she said:

It surely will not be denied that women have, and ought to have, opinions of their own on subjects of public interest, and on the events which arise as the world wends on its way. But if it be granted that women may, without offence, hold political opinions, on what ground can the right be withheld of giving the same expression or effect to their opinions as that enjoyed by their male neighbours?[3]

Two further petitions were presented to parliament in May 1867 and Mill also proposed an amendment to the 1867 Reform Act to give women the same political rights as men but the amendment was treated with derision and defeated by 196 votes to 73.[4]

The first public meeting on the subject of women's suffrage in UK was held in Manchester's Free Trade Hall in 1868; one of the speakers was Lydia Becker, supported by Dr. Richard Pankhurst among others. Amongst the audience was the 15-year-old Emmeline Goulden, who was to become an ardent campaigner for women's rights, and later married Dr. Pankhurst and adopted his surname as was customary, becoming known as Emmeline Pankhurst.[5]

During the summer of 1880, Lydia Becker visited the Isle of Man to address five public meetings on the subject of women's suffrage to audiences mainly composed of women. These speeches instilled in the Manx women a determination to secure the franchise, and on 31 January 1881, women on the island who owned property in their own right were given the vote.[6]

In Manchester the Women's Suffrage Committee had been formed in 1867 to work with the Independent Labour Party (ILP) to secure votes for women, but although the local ILP were very supportive, nationally the party were more interested in securing the franchise for working class men and refused to make women's suffrage a priority. In 1897 the Manchester Women's Suffrage committee had merged with the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) but Emmeline Pankhurst, who was a member of the original Manchester committee, and her eldest daughter Christabel had become impatient with the ILP and on 10 October 1903, Emmeline Pankhurst held a meeting at her home in Manchester to form a breakaway group, the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). From the outset the WSPU was determined to move away from the staid campaign methods of NUWSS and instead take more positive action:[7]

It was on October 10, 1903 that I invited a number of women to my house in Nelson Street, Manchester, for purposes of organisation. We voted to call our new society the Women's Social and Political Union, partly to emphasise its democracy, and partly to define it object as political rather than propagandist. We resolved to limit our membership exclusively to women, to keep ourselves absolutely free from party affiliation, and to be satisfied with nothing but action on our question. 'Deeds, not words' was to be our permanent motto.

— Emmeline Pankhurst[8]

The term "suffragette" was first used as a term of derision by the journalist Charles E. Hands in the London Daily Mail to describe activists in the movement for women's suffrage, in particular members of the WSPU.[9][10] But the women he intended to ridicule embraced the term, saying "suffraGETtes" (hardening the g), implying not only that they wanted the vote, but that they intended to get it.[11]

The WSPU campaign

At a political meeting in Manchester in 1905, Christabel Pankhurst and millworker, Annie Kenney, disrupted speeches by prominent Liberals Winston Churchill and Sir Edward Grey, asking where Churchill and Grey stood with regards to women's political rights. At a time when political meetings were only attended by men and speakers were expected to be given the courtesy of expounding their views without interruption, the audience were outraged, and when the women unfurled a "Votes for Women" banner they were both arrested for a technical assault on a policeman. When Pankhurst and Kenny appeared in court they both refused to pay the fine imposed, preferring to go to prison in order to gain publicity for their cause.[12]

Stung by the stereotypical image of the strong minded woman in masculine clothes created by newspaper cartoonists, the suffragettes resolved to present a fashionable, feminine image when appearing in public. In 1908 the co-editor of Votes for Women, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, designed the suffragettes' colour scheme of purple for loyalty and dignity, white for purity, and green for hope. Fashionable London shops Selfridges and Liberty sold tricolour-striped ribbon for hats, rosettes, badges and belts, as well as coloured garments, underwear, handbags, shoes, slippers and toilet soap.[13] As membership of the WSPU grew it became fashionable for women to identify with the cause by wearing the colours, often discretely in a small piece of jewellery or by carrying a heart-shaped vesta case[14][13] and in December 1908 the London jewellers, Mappin & Webb, issued a catalogue of suffragette jewellery in time for the Christmas season.[15] Sylvia Pankhurst said at the time: "Many suffragists spend more money on clothes than they can comfortably afford, rather than run the risk of being considered outré, and doing harm to the cause".[13] In 1909 the WSPU presented specially commissioned pieces of jewellery to leading suffragettes, Emmeline Pankhurst and Louise Eates.[15]

The suffragettes also used other methods to publicise and raise money for the cause and from 1909, the "Pank-A-Squith" board game was sold by the WSPU. The name was derived from Pankhurst and the surname of Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, who was largely hated by the movement. The board game was set out in a spiral, and players were required to lead their suffragette figure from their home to parliament, past the obstacles faced from Prime Minister H. H. Asquith and the Liberal government.[16] Also in 1909, suffragettes Solomon and McLellan tried an innovative method of potentially obtaining a meeting with Asquith by sending themselves by Royal Mail courier post, however, Downing Street did not accept the parcel.[17]

Sophia Duleep Singh, the third daughter of the exiled, Maharaja Duleep Singh,[18] had made a trip from her home in London to India, in 1903, to see the celebrations for the accession of King Edward VII as emperor of India and was shocked by the brutality of life under British rule. On her return to the UK in 1909, Singh became an ardent supporter of the cause, selling suffragette newspapers outside her apartment at Hampton Court Palace, refusing to pay taxes, fighting with police at protests and attacking the prime minister's car.[19][20]

1912 was a turning point for the suffragettes as they turned to using more militant tactics, chaining themselves to railings, setting fire to post box contents, smashing windows and occasionally detonating bombs.[21] Some radical techniques used by the suffragettes were learned from Russian exiles from tsarism who had escaped to England.[22] In 1914, at least seven churches were bombed or set on fire across the United Kingdom, including Westminster Abbey, where an explosion aimed at destroying the 700-year-old Coronation Chair, only caused minor damage.[23]

One suffragette, Emily Davison, died under the King's horse, Anmer, at The Derby on 4 June 1913. It is debated whether she was trying to pull down the horse, attach a suffragette scarf or banner to it, or commit suicide to become a martyr to the cause. However, recent analysis of the film of the event suggests that she was merely trying to attach a scarf to the horse, and the suicide theory seems unlikely as she was carrying a return train ticket from Epsom and had holiday plans with her sister in the near future.[24]

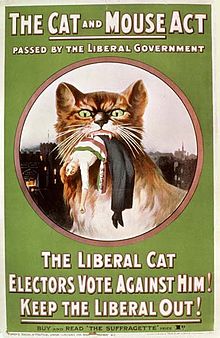

Many suffragettes were imprisoned and refused food as a scare tactic against the government. The Liberal government of the day led by Asquith responded with the Cat and Mouse Act.

Imprisonment

In the early 20th century until the outbreak of World War I, approximately one thousand suffragettes were imprisoned in Britain.[25] Most early incarcerations were for public order offences and failure to pay outstanding fines. While incarcerated, suffragettes lobbied to be considered political prisoners; with such a designation, suffragettes would be placed in the First Division as opposed to the Second or Third Division of the prison system, and as political prisoners would be granted certain freedoms and liberties not allotted to other prison divisions, such as being allowed frequent visits and being allowed to write books or articles.[26] Because of a lack of consistency between the different courts, suffragettes would not necessarily be placed in the First Division and could be placed in Second or Third Division, which enjoyed fewer liberties.

This cause was taken up by the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), a large organisation in Britain, that lobbied for women's suffrage led by militant suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst.[27] The WSPU campaigned to get imprisoned suffragettes recognised as political prisoners. However, this campaign was largely unsuccessful. Citing a fear that the suffragettes becoming political prisoners would make for easy martyrdom,[28] and with thoughts from the courts and the Home Office that they were abusing the freedoms of First Division to further the agenda of the WSPU,[29] suffragettes were placed in Second Division, and in some cases the Third Division, in prisons with no special privileges granted to them as a result.[30]

Civil disobedience

Peaceful acts of civil disobedience such as chaining themselves to railings, refusing to pay taxes and fines, and hunger strikes were deployed by the suffragettes.

Arson, bombs, and property damage

Throughout the suffragette movement many violent tactics were employed in order to achieve its goals. Throughout Britain, the contents of letter boxes were set alight or corrosive acids or liquids poured over the letters inside, and shop and office windows were smashed. Telephone wires were cut, and graffiti slogans began appearing on the streets. Places that wealthy people, typically men, frequented were also burnt and destroyed while unattended so that there was no risk to life, including cricket grounds, golf courses and horse-racing tracks.[31] Pinfold Manor in Surrey, which was being built for Chancellor of the exchequer, David Lloyd George, was targeted with two bombs on 19 February 1913, only one of which exploded, causing significant damage; in her memoirs, Sylvia Pankhurst said that Emily Davison had carried out the attack.[31] There were 250 arson or destruction attacks in a six-month period in 1913.[31] There are reports in the Parliamentary Papers which include lists of the 'incendiary devices', explosions, artwork destruction (including an axe attack upon a painting of The Duke of Wellington in the National Gallery), arson attacks, window-breaking, post-box burning and telegraph cable breaking that took place during the most militant years, from 1910 to 1914.[citation needed] Both suffragettes and police spoke of a "Reign of Terror"; newspaper headlines referred to "Suffragette Terrorism".[32]

Hunger strikes

Suffragettes were not recognised as political prisoners and many of them staged hunger strikes while they were imprisoned. The first woman to refuse food was Marion Wallace Dunlop, a militant suffragette who was sentenced to a month in Holloway for vandalism in July 1909.[33] Without consulting suffragette leaders such as Pankhurst,[34] Dunlop refused food in protest at being denied political prisoner status. After a 92-hour hunger strike, and for fear of her becoming a martyr,[34] the Home Secretary Herbert Gladstone decided to release her early on medical grounds.[29] Dunlop's strategy was adopted by other suffragettes who were incarcerated.[35] It became common practice for suffragettes to refuse food in protest for not being designated as political prisoners, and as a result they would be released after a few days and could return to the "fighting line".[36]

After a public backlash regarding the prison status of suffragettes, the rules of the divisions were amended. In March 1910, Rule 243A was introduced by the Home Secretary Winston Churchill, allowing prisoners in Second and Third Divisions to be allowed certain privileges of the First Division, provided they were not convicted of a serious offence, effectively ending hunger strikes for two years.[37] Hunger strikes began again when Pankhurst was transferred from the Second Division to the First Division, inciting the other suffragettes to demonstrate regarding their prison status.[38]

Militant suffragette demonstrations subsequently became more aggressive,[29] and the British Government took action. Unwilling to release all the suffragettes refusing food in prison,[35] in the autumn of 1909, the authorities began to adopt more drastic measures to manage the hunger-strikers.

Force-feeding

In September 1909, the Home Office became unwilling to release hunger-striking suffragettes before their sentence was served.[36] Suffragettes became a liability because if they were to die in custody, the prison would be responsible for their death. Prisons began the practice of force-feeding the hunger strikers through a tube, most commonly via a nostril or stomach tube or a stomach pump.[35] Force-feeding had previously been practised in Britain but its use had been exclusively for patients in hospitals who were too unwell to eat or swallow food. Despite the practice being deemed safe by medical practitioners for sick patients, it posed health issues for the healthy suffragettes.[34]

The process of tube-feeding was strenuous without the consent of the hunger strikers, who were typically strapped down and force-fed via stomach or nostril tube, often with a considerable amount of force.[39] The process was painful and after the practice was observed and studied by several physicians, it was deemed to cause both short-term damage to the circulatory system, digestive system and nervous system and long-term damage to the physical and mental health of the suffragettes.[40] Some suffragettes who were force-fed developed pleurisy or pneumonia as a result of a misplaced tube.[41]

Legislation

In April 1913, Reginald McKenna of the Home Office passed the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act 1913, or the Cat and Mouse Act as it was commonly known. The act made the hunger strikes legal, in that a suffragette would be temporarily released from prison when their health began to diminish, only to be readmitted when she regained her health to finish her sentence.[39] The act enabled the British Government to be absolved of any blame resulting from death or harm due to the self-starvation of the striker and ensured that the suffragettes would be too ill and too weak to participate in demonstrative activities while not in custody.[35] Most women continued hunger striking when they were readmitted to prison following their leave.[42] After the Act was introduced, force-feeding on a large scale was stopped and only women convicted of more serious crimes and considered likely to repeat their offences if released were force-fed.[43]

The Bodyguard

In early 1913 and in response to the Cat and Mouse Act, the WSPU instituted a secret society of women known as the "Bodyguard" whose role was to physically protect Emmeline Pankhurst and other prominent suffragettes from arrest and assault. Known members included Katherine Willoughby Marshall, Leonora Cohen and Gertrude Harding; Edith Margaret Garrud was their jujitsu trainer.

The origin of the "Bodyguard" can be traced to a WSPU meeting at which Garrud spoke. As suffragettes speaking in public increasingly found themselves the target of violence and attempted assaults, learning jujitsu was a way for women to defend themselves against angry hecklers.[44] Inciting incidents included Black Friday, during which a deputation of 300 suffragettes were physically prevented by police from entering the House of Commons, sparking a near-riot and allegations of both common and sexual assault.

Members of the "Bodyguard" orchestrated the "escapes" of a number of fugitive suffragettes from police surveillance during 1913 and early 1914. They also participated in several violent actions against the police in defence of their leaders, notably including the "Battle of Glasgow" on March 9, 1914, when a group of about 30 Bodyguards brawled with about 50 police constables and detectives on the stage of St. Andrew's Hall in Glasgow, Scotland. The fight was witnessed by an audience of some 4500 people.[45]

World War

At the commencement of the World War 1, the suffragette movement in Britain moved away from suffrage activities and focused their efforts on the war effort, and as a result, hunger strikes largely stopped.[46] In August 1914, the British Government released all prisoners who had been incarcerated for suffrage activities on an amnesty,[47] with Pankhurst ending all militant suffrage activities soon after.[48] The suffragettes' focus on war work turned public opinion in favour of their eventual partial enfranchisement in 1918.[49]

Women eagerly volunteered to take on many traditional male roles – leading to a new view of what women were capable of. The war also caused a split in the British suffragette movement; the mainstream, represented by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst's WSPU calling a ceasefire in their campaign for the duration of the war, while more radical suffragettes, represented by Sylvia Pankhurst's Women's Suffrage Federation continued the struggle.

The National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, which had always employed "constitutional" methods, continued to lobby during the war years and compromises were worked out between the NUWSS and the coalition government.[50] On 6 February, the Representation of the People Act 1918 was passed, enfranchising all men over 21 years of age and women over the age of 30 who met minimum property qualifications,[51][52] gaining the right to vote for about 8.4 million women.[52] In November 1918, the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918 was passed, allowing women to be elected into parliament.[52] The Representation of the People Act 1928 extended the voting franchise to all women over the age of 21, granting women the vote on the same terms that men had gained ten years earlier.[53]

1918 general election, women Members of Parliament

The 1918 general election, the first general election to be held after the Representation of the People Act 1918, was the first in which some women (property owners older than 30) could vote. At that election, the first woman to be elected an MP was Constance Markievicz but, in line with Sinn Féin abstentionist policy, she declined to take her seat in the British House of Commons. The first woman to do so was Nancy Astor, Viscountess Astor, following a by-election in November 1919.

Legacy

In the autumn of 1913 Emmeline Pankhurst had sailed to the US to embark on a lecture tour to publicise the message of the WSPU and to raise money for the treatment of her son, Harry, who was gravely ill. By this time the suffragettes' tactics of civil disorder were being used by American militants Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, both of whom had campaigned with the WSPU in London. As in the UK, the suffrage movement in America was divided into two disparate groups with the National American Woman Suffrage Association representing the more militant campaign and the International Women's Suffrage Alliance taking a more cautious and pragmatic approach[54] Although the publicity surrounding Pankhurst's visit and the militant tactics used by her followers gave a welcome boost to the campaign,[55] the majority of women in the US preferred the more respected label of "suffragist" to the title "suffragette" adopted by the militants.[56]

Many suffragists at the time, and some historians since, have argued that the actions of the militant suffragettes damaged their cause.[57] Opponents at the time saw evidence that women were too emotional and could not think as logically as men.[58][59][60][61][62] Historians generally argue that the first stage of the militant suffragette movement under the Pankhursts in 1906 had a dramatic mobilizing effect on the suffrage movement. Women were thrilled and supportive of an actual revolt in the streets; the membership of the militant WSPU and the older NUWSS overlapped and were mutually supportive. However a system of publicity, Ensor argues, had to continue to escalate to maintain its high visibility in the media. The hunger strikes and force-feeding did that. However, the Pankhursts refused any advice and escalated their tactics. They turned to systematic disruption of Liberal Party meetings as well as physical violence in terms of damaging public buildings and arson. Searle says the methods of the suffragettes did succeed in damaging the Liberal party but failed to advance the cause of women's suffrage. When the Pankhursts decided to stop the militancy at the start of the war, and enthusiastically support the war effort, the movement split and their leadership's role ended. Suffrage did come four years later, but the feminist movement in Britain permanently abandoned the militant tactics that had made the suffragettes famous.[63][64]

After Emmeline Pankhurst's death in 1928, money was raised to commission a statue, and on 6 March 1930 the statue in Victoria Tower Gardens was unveiled. A crowd of radicals, former suffragettes, and national dignitaries gathered as former Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin presented the memorial to the public. In his address, Baldwin declared: "I say with no fear of contradiction, that whatever view posterity may take, Mrs. Pankhurst has won for herself a niche in the Temple of Fame which will last for all time."[65] In 1929 a portrait of Emmeline Pankhurst was added to the National Portrait Gallery's collection. In 1987 her former home at 62 Nelson Street, Manchester, the birhplace of the WSPU, and the adjoining Edwardian villa (no. 60) were opened as the Pankhurst Centre, a women-only space and museum dedicated to the suffragette movement.[66] Christabel Pankhurst was appointed a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1936, and after her death in 1958 a permanent memorial was installed next to the statue of her mother.[67] The memorial to Christabel Panhhurst consists of a low stone screen flanking her mother's statue with a bronze medallion plaque depicting her profile at one end of the screen paired with a second plaque depicting the "prison brooch" or "badge" of the WSPU at the other end.[68] The unveiling of this dual memorial was performed on 13 July 1959 by the Lord Chancellor, Lord Kilmuir.[69]

In 1903 Australian suffragist Vida Goldstein adopted the WSPU colours for her campaign for the Senate in 1910 but got them slightly wrong, thinking they were purple, green and lavender. Goldstein had visited England in 1911 at the behest of the WSPU; her speeches around the country drew huge crowds and her tour was touted as "the biggest thing that has happened in the women movement for sometime in England".[70] The correct colours were used for her campaign for Kooyong in 1913 and also for the flag of the Women's Peace Army, which she established during World War I to oppose conscription. During International Women's Year in 1975 the BBC series about the suffragettes, Shoulder to Shoulder, was screened across Australia and Elizabeth Reid, Women's Adviser to Prime Minister Gough Whitlam directed that the WSPU colours be used for the International Women's Year symbol; they were also used for a first-day cover and postage stamp released by Australia Post in March 1975. The colours have since been adopted by government bodies such as the National Women's Advisory Council and organisations such as Women's Electoral Lobby and other women's services such as domestic violence refuges and are much in evidence each year on International Women's day.[71]

The colours of green and heliotrope (purple) were commissioned into a new coat of arms for Edge Hill University in Lancashire in 2006, symbolising the university's early commitment to the equality of women through its beginnings as a women-only college.[72]

During the 1960s the memory of the suffragettes was kept alive in the public consciousness by portrayals in film, such as the character Mrs. Banks in the 1964 Disney musical film Mary Poppins who sings the song Sister Suffragette and Maggie DuBois in the 1965 film The Great Race. In 1974 The BBC TV series Shoulder to Shoulder portraying events in the British militant suffrage movement, concentrating on the lives of members of the Pankhurst family was shown around the world. And in the 21st century the story of the suffragettes was brought to a new generation in the BBC television series Up the Women, The 2015 graphic novel trilogy Suffrajitsu: Mrs. Pankhurst's Amazons and the 2015 film Suffragette.

Notable people

Great Britain

- Gertrude Ansell

- Joan Beauchamp

- Rosa May Billinghurst

- Elsie Bowerman

- Lady Constance Bulwer-Lytton

- Mabel Capper

- Ada Nield Chew

- Anne Cobden-Sanderson

- Leonora Cohen

- Jessie Craigen

- Emily Wilding Davison

- Flora Drummond

- Sophia Duleep Singh

- Norah Elam also known as Norah Dacre Fox[73]

- Jane Ellen Harrison

- Edith How-Martyn

- Clemence Housman

- Elsie Inglis

- Grace Kimmins

- Lilian Lenton

- Lizzy Lind af Hageby

- Mary Lowndes

- Nellie Martel

- Selina Martin

- Adela Pankhurst

- Frances Parker

- Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence

- Mary Richardson

- Edith Rigby

- Ethel Smyth

- Ethel Snowden

- Dora Thewlis

- Leonora Tyson

- Vera Wentworth

- Olive Wharry

- Cicely Hamilton

- Elizabeth Garrett Anderson

Ireland

- Louie Bennett

- Frances Power Cobbe

- Charlotte Despard

- Eva Gore-Booth

- Anna Haslam

- Mary Hayden

- Kathleen Lynn

- Constance Markievicz

- Margaret McCoubrey

- Mary Ann McCracken

- Mary MacSwiney

- Helena Molony

- Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington

- Anna Wheeler

- Jenny Wyse Power

- Mary Fleetwood Berry

- Helen Chenevix

- Margaret "Gretta" Cousins

- Norah Elam

- Florence Moon

- Mary Donovan O'Sullivan

- Sarah Persse

- Isabella Tod

Gallery

-

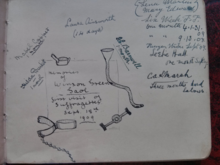

UK WSPU Hunger Strike Medal 30 July 1909 including the bar 'Fed by Force 17 September 1909'. The Medal awarded to Mabel Capper records the first instance of forcible feeding of hunger striking Suffragette prisoners in England at Winson Green Prison in Birmingham.

-

Portrait badge of Emmeline Pankhurst (c. 1909) sold in large numbers by the WSPU to raise funds

-

1910 Suffragette calendar held in the collections of the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry

-

Suffragette Banner (c. 1910)

-

Votes for Women poster (1909)

-

7 October 1913 edition of The Suffragette

-

Gold earrings in suffragette colours

See also

- Pankhurst Centre

- Women's suffrage

- Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom

- Women's suffrage organisations

- Women's suffrage in the United States

- List of women's rights activists

- Suffragetto board game

References

- ^ Anon. "John Stuart Mill and the 1866 petition". UK Parliament. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ Herbert, Michael. "Lydia Becker (1827–1890): the fight for votes for women". Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ The Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art, Volume 5; Volume 68. 1867. p. 707. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Simkin, John. "John Stuart Mill". Spartacus Educational Publishers Ltd. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ Culbertson, Alix. "The Suffragettes: The women who risked all to get the vote". Sky UK. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ Anon. "The struggle behind the quest to secure the vote for women". IOM Today. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ Anon. "Suffragette history". Pankhurst centre. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ Pankhurst, Emmeline. My Own Story. 1914. London: Virago Limited, 1979. ISBN 0-86068-057-6

- ^ Crawford 1999, p. 452.

- ^ Ben Walsh. GCSE Modern World History second edition (Hodder Murray, 2008) p. 60.

- ^ Colmore, Gertrude. Suffragette Sally. Broadview Press, 2007, p. 14

- ^ Trueman, C.N. "Women's Social and Political Union". History learning site. C.N. Trueman. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ a b c Blackman, Cally (8 October 2015). "How the Suffragettes used fashion to further the cause". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ^ Crawford 1999, pp. 136–7

- ^ a b Hughes, Ivor (March 2009). "Suffragette Jewelry, Or Is It?". Antiques Journal. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Collection Highlights, Pank-A-Squith Board Game, People's History Museum

- ^ Time Stokes (21 December 2017). "The strangest things sent in the post". BBC news. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ Sarna, Navtej (23 January 2015). "The princess dares: Review of Anita Anand's book "Sophia"". India Today News Magazine.

- ^ "With 'Sophia,' A Forgotten Suffragette Is Back In The Headlines". NPR.org. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ^ "Princess Sophia Duleep Singh – Timeline". History Heroes organization.

- ^ "SUFFRAGETTES". The Register. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 16 April 1913. p. 7. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ Grant 2011.

- ^ "Bomb explosion in Westminster Abbey; Coronation Chair damaged; Suffragette outrage". The Daily Telegraph. 12 June 1914. p. 11.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (26 May 2013). "Truth behind the death of suffragette Emily Davison is finally revealed". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited.

- ^ Purvis 1995, p. 103 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPurvis1995 (help).

- ^ Purvis, June (March–April 1995). "Deeds, not words: The daily lives of militant suffragettes in Edwardian Britain". Women's Studies International Forum. 18 (2). ScienceDirect: 97. doi:10.1016/0277-5395(95)80046-R.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Purvis 1995, p. 104 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPurvis1995 (help).

- ^ Williams 2001, p. 285.

- ^ a b c Geddes 2008, p. 81.

- ^ Williams, Elizabeth (December 2008). "Gags, funnels and tubes: forced feeding of the insane and of suffragettes". Endeavour. 32 (4). PubMed: 134. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2008.09.001. PMID 19019439.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b c Porter, Ian. "Suffragette attack on Lloyd-George". London walks. London Town Walks. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ "Kitty Marion: The actress who became a 'terrorist'". BBC News. 27 May 2018. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ^ Purvis, ""Deeds, Not Words"", 97

- ^ a b c Miller 2009, p. 360.

- ^ a b c d Miller 2009, p. 361.

- ^ a b Geddes 2008, p. 82.

- ^ Geddes 2008, pp. 84–5.

- ^ Geddes 2008, p. 85.

- ^ a b Purvis, "Deeds, Not Words", 97.

- ^ Williams, "Gags, funnels and tubes", 138.

- ^ Geddes 2008, p. 83.

- ^ Geddes 2008, p. 88.

- ^ Geddes 2008, p. 89.

- ^ Ruz, Camila; Magazine, Justin Parkinson BBC News. "'Suffrajitsu': How the suffragettes fought back using martial arts". BBC News. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- ^ Wilson, Gretchen With All Her Might: The Life of Gertrude Harding, Militant Suffragette (Holmes & Meier Publishing, April 1998)

- ^ Williams, "Gags, funnels and tubes", 139.

- ^ Geddes 2008, p. 92.

- ^ Purvis 1995, p. 123 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPurvis1995 (help).

- ^ J. Graham Jones, "Lloyd George and the Suffragettes", National Library of Wales Journal (2003) 33#1 pp. 1–34

- ^ Ian Cawood, David McKinnon-Bell (2001). "The First World War". p.71. Routledge 2001

- ^ "Britain marks a century of votes for women". The Economist. The Economist. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ^ a b c Fawcett, Millicent Garrett. The Women's Victory – and After. p.170. Cambridge University Press

- ^ Peter N. Stearns (2008).In 1979 the first British women prime minister Margaret came> The Oxford encyclopedia of the modern world, Volume 7. p.160. Oxford University Press, 2008

- ^ Bartley, Paula (2012). Emmeline Pankhurst. Routledge. p. 161. ISBN 113512096X.

- ^ Anon. "When Civil War is Waged by Women". History is a lesson. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ^ Steinmetz, Katy (22 October 2015). "Everything You Need to Know About the Word 'Suffragette'". Time. time.comurl=http://time.com/4079176/suffragette-word-history-film/.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Howell, Georgina (2010). Gertrude Bell: Queen of the Desert, Shaper of Nations. p. 71.

- ^ Harrison 2013, p. 176.

- ^ Pedersen 2004, p. 124.

- ^ Bolt 1993, p. 191.

- ^ "Did the Suffragettes Help?". Claire. John D. (2002/2010), Greenfield History Site. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- ^ "The Suffragettes: Deeds not words" (PDF). National Archives. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- ^ Robert Ensor, England: 1870–1914 (1936) pp 398–99

- ^ G.R. Searley, A New England? Peace and War 1886–1918 (2004) pp 456–70. quote p 468

- ^ Purvis, June (2002). Emmeline Pankhurst: A Biography. London: Routledge. p. 357. ISBN 0-415-23978-8.

- ^ Bartley, Paula (2002). Emmeline Pankhurst. London: Routledge. pp. 240–241. ISBN 0-415-20651-0.

- ^ Larsen, Timothy (2002). Christabel Pankhurst: Fundamentalism and Feminism in Coalition (Studies in Modern British Religious History). Boydell Press. p. vii.

- ^ Holloway brooch, Parliament of the United Kingdom

- ^ Ward-Jackson, Philip (2011), Public Sculpture of Historic Westminster: Volume 1, Public Sculpture of Britain, vol. 14, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, pp. 382–5

- ^ Alice Henry (1911) Vida Goldstein Papers, 1902–1919. LTL:V MSS 7865

- ^ Anon. "Purple, Green and White: An Australian History". MAAS. MAAS. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ^ "Colours, Crest & Mace". Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ McPherson, Angela; McPherson, Susan (2011). Mosley's Old Suffragette – A Biography of Norah Elam. ISBN 978-1-4466-9967-6. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Works cited

- Bolt, Christine (1993). The Women's Movements in the United States and Britain from the 1790s to the 1920s. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 978-0-870-23866-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crawford, Elizabeth (1999). The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide, 1866–1928. London: UCL Press. ISBN 978-1-841-42031-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Geddes, J. F. (2008). "Culpable Complicity: the medical profession and the forcible feeding of suffragettes, 1909–1914". Women's History Review. 17 (1): 79–94. doi:10.1080/09612020701627977.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Grant, Kevin (2011). "British suffragettes and the Russian method of hunger strike". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 53 (1): 113–143. doi:10.1017/S0010417510000642.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Harrison, Brian (2013) [1978]. Separate Spheres: The Opposition to Women's Suffrage in Britain. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-62336-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Miller, Ian (2009). "Necessary Torture? Vivisection, Suffragette Force-Feeding, and Responses to Scientific Medicine in Britain c. 1870–1920". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 64 (3): 333–372. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrp008.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Pedersen, Susan (2004). Eleanor Rathbone and the Politics of Conscience. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10245-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Purvis, June (1995). "The Prison Experiences of the Suffragettes in Edwardian Britain". Women's History Review. 4 (1): 103–133. doi:10.1080/09612029500200073.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Williams, John (2001). "Hunger Strikes: A Prisoner's Right or a 'Wicked Folly'?". Howard Journal. 40 (3): 285–296. doi:10.1111/1468-2311.00208.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Atkinson, Diane (1992). The Purple, White and Green: Suffragettes in London, 1906–14. London: Museum of London. ISBN 978-0-904-81853-6.

- Dangerfield, George. The Strange Death of Liberal England (1935) online free; Classic account of how the Liberal Party ruined itself in dealing with the House of Lords, woman suffrage, the Irish question, and labour unions, 1906-1914.

- Hannam, June (2005). "International Dimensions of Women's Suffrage: 'at the crossroads of several interlocking identities'". Women's History Review. 14 (3–4): 543–560. doi:10.1080/09612020500200438.

- Leneman, Leah (1995). A Guid Cause: The Women's Suffrage Movement in Scotland (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Mercat Press. ISBN 978-1-873-64448-5.

- Liddington, Jill; Norris, Jill (2000). One Hand Tied Behind Us: The Rise of the Women's Suffrage Movement (2nd ed.). London: Rivers Oram Press. ISBN 978-1-854-89110-5.

- Mayhall, Laura E. Nym (2000). "Reclaiming the Political: Women and the Social History of Suffrage in Great Britain, France, and the United States". Journal of Women's History. 12 (1): 172–181. doi:10.1353/jowh.2000.0023.

- ——— (2003). The Militant Suffrage Movement: Citizenship and Resistance in Britain, 1860–1930. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-15993-6.

- Pankhurst, Sylvia (1911). The suffragette; the history of the women's militant suffrage movement, 1905–1910. New York: Sturgis & Walton Company.

- Purvis, June (2002). Emmeline Pankhurst: A Biography. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-23978-3.

- Purvis, June; Sandra, Stanley Holton, eds. (2000). Votes For Women. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21458-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editorlink=ignored (|editor-link=suggested) (help) - Rosen, Andrew (2013) [1974]. Rise Up Women!: The Militant Campaign of the Women's Social and Political Union, 1903–1914 (Reprint ed.). Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-62384-1.

- Smith, Harold L. (2010). The British Women's Suffrage Campaign, 1866–1928 (Revised 2nd ed.). Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-408-22823-4.

- Wingerden, Sophia A. van (1999). The Women's Suffrage Movement in Britain, 1866–1928. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-66911-2.

External links

- UNCG Special Collections and University Archives selections of American Suffragette manuscripts

- Collection of Suffrage posters housed at Cambridge University.

- The struggle for democracy Visit the British Library learning resource pages to discover more about the suffragette movement

- Suffragettes versus Suffragists – website comparing aims and methods of Women's Social and Political Union (Suffragettes) to National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (Suffragists)

- Exploring 20th century London – Women's Social and Political Union (W.S.P.U.) Objects and photographs including hunger strike medal's given to activists.

- Antiques Journal Information on Suffragette jewellery

- Museum of Australian Democracy: Pank-a-Squith Information on the 1913 board game