Father

A father is the male parent of a child. Besides the paternal bonds of a father to his children, the father may have a parental, legal, and social relationship with the child that carries with it certain rights and obligations. An adoptive father is a male who has become the child's parent through the legal process of adoption. A biological father is the male genetic contributor to the creation of the infant, through sexual intercourse or sperm donation. A biological father may have legal obligations to a child not raised by him, such as an obligation of monetary support. A putative father is a man whose biological relationship to a child is alleged but has not been established. A stepfather is a male who is the husband of a child's mother and they may form a family unit, but who generally does not have the legal rights and responsibilities of a parent in relation to the child.

The adjective "paternal" refers to a father and comparatively to "maternal" for a mother. The verb "to father" means to procreate or to sire a child from which also derives the noun "fathering". Biological fathers determine the sex of their child through a sperm cell which either contains an X chromosome (female), or Y chromosome (male).[1] Related terms of endearment are dad (dada, daddy), papa, pappa, papasita, (pa, pap) and pop. A male role model that children can look up to is sometimes referred to as a father-figure.

Paternal rights

The paternity rights of a father with regard to his children differ widely from country to country often reflecting the level of involvement and roles expected by that society.

- Paternity leave

Parental leave is when a father takes time off to support his newly born or adopted baby.[2] Paid paternity leave first began in Sweden in 1976, and is paid in more than half of European Union countries.[3] In the case of male same-sex couples the law often makes no provision for either one or both fathers to take paternity leave.

- Child custody

Fathers' rights movements such as Fathers 4 Justice argue that family courts are biased against fathers.[4]

- Child support

Child support is an ongoing periodic payment made by one parent to the other; it is normally paid by the parent who does not have custody.

- Paternity fraud

An estimated 2% of British fathers experiences paternity fraud during a non-paternity event, bringing up a child they wrongly believe to be their biological offspring.[5]

Role of the father

In almost all cultures fathers are regarded as secondary caregivers. This perception is slowly changing with more and more fathers becoming primary caregivers, while mothers go to work or in single parenting situations, male same-sex parenting couples.

- Fatherhood in the Western World

In the West, the image of the married father as the primary wage-earner is changing. The social context of fatherhood plays an important part in the well-being of men and all their children.[6] In the United States 16% of single parents were men as of 2013.[7]

- Importance of father or father-figure

In America it is not unusual to be in a single-parent household. In the time span between 1960 and 1990, there were significant findings that revealed a decreasing rate of fathers in a family home. In-between this time period, the span of three decades, “the percentage of children living apart from their biological fathers more than doubled, from 17 percent to 36 percent.”[8] This increasing rate of a decreased father-presence in the household tremendously impacted children and would continue to negatively impact their lives if the rate continued to decline. “If this rate continues, by the turn of the century nearly 50% of American children will be going to sleep each night without being able to say goodnight to their dads.”[8] This trend, beginning in the 1960s, was not expected.

The reasoning for these departures were branched from many different motives; however, the main force driving fathers away was due to divorce (others can be military, death, or desertion). In 1974, “more marriages ended in divorce than in death” and this pattern has not declined.[8] When two individuals get divorced, the biological parent that obtains full custody of the child is “nearly always the mother.”[8] This can be due to many different factors; however, “men are not biologically as attuned to being committed fathers as women are to being committed mothers.”[8] This reveals that American children lack a father's impact the most in their developing stages of life. Many of the “attention-grabbing issues that dominate the news”, such as, “crime and delinquency; premature sexuality and out-of-wed-lock teen births; deteriorating educational achievement; depression, substance abuse, and alienation among teenagers; and the growing number of women and children in poverty" are due to father absence.[8] A father’s presence for a child’s full social and cognitive development is important; therefore, being fatherless is not beneficial for a child.

Involved fathers offer developmentally specific provisions to their children and are impacted themselves by doing so. Active father figures may play a role in reducing behavior and psychological problems in young adults.[9] An increased amount of father–child involvement may help increase a child's social stability, educational achievement, and their potential to have a solid marriage as an adult. Their children may also be more curious about the world around them and develop greater problem solving skills.[10] Children who were raised with fathers perceive themselves to be more cognitively and physically competent than their peers without a father.[11] Mothers raising children together with a father reported less severe disputes with their child.[12]

The father-figure is not always a child's biological father and some children will have a biological father as well as a step- or nurturing father. When a child is conceived through sperm donation, the donor will be the "biological father" of the child.

Fatherhood as legitimate identity can be dependent on domestic factors and behaviors. For example, a study of the relationship between fathers, their sons, and home computers found that the construction of fatherhood and masculinity required that fathers display computer expertise.[13]

Importance shown through multiple cultures

American

Without a father in a child’s life, they go through many developmental changes that can negatively effect many aspects of their life. Culture and biology are two driving factors that create a father’s impact to be different than a mother’s impact. In the American culture, fathers “are more active and arousing in their nurturing activities, fostering certain physical skills and emphasizing autonomy and independence.”[14] The decision-making in children is found to be altered from the lack of these father-child interactions. Ronald J. Angel and Jacqueline L. Angel, sociologists from the University of Texas, have shown that fatherlessness is a “mental health risk factor for children.”[14] They have shown through studies that a child’s social development is hindered without the physical interactions that a father gives a child. These impaired social developments have the ability to lead children to be “three times more likely to have a child out of wedlock, 2.5 times more likely to become teen mothers, twice as likely to drop out of high school, and 1.4 times more likely to be idle.”[14] A father has a very important role in how their children choose what is important in their life and how children interact with their peers.

There is also a diminishing cognitive piece to these children’s lives. The article by Marybeth Shinn, reveals that fatherless families “is often associated with poor performance on cognitive tests.”[15] One of the most unique findings was that fatherless children would score “relatively low quantitative and high verbal scores on aptitude tests", while children with a fathers presence had more equal scores for both sections of the exam.[15] This observation concludes that a father’s impact is different than a mother’s. A father brings different values and skills into a child’s life and without their impact a child could have lower developmental areas of performance. Any reduction of interaction with parents has the ability to decrease a children’s cognitive development. However, not all of the cognitive withdrawal is directly correlated to the fathers lack of interactions. Other data from this article show that the environmental changes such as the role of anxiety and financial problems increases the decreased test scores as well.

Studies done in the study that support these findings:

Study by: Blanchard and Biller

Who: “44 working-and lower-middle-class 3rd grade boys”[15]

Family life of the different groups:

· “11 father absent before age 5”[15]

· “11 father absent after age 5”[15]

· “11 low father present”[15]

· “11 high father present”[15]

Results: All of the 10 achievement scales had higher scores by all the participants with a father present. There wasn’t a unique difference in the scores when comparing them between the two different fatherless groups; therefore, revealing that there is a significant difference in the cognitive development of children who grow up with or without a father.

Study by: Jaffe

Who: “8th grade black students from Detroit”[15]

Family life of the different groups:

· "Father present and employed"[15]

· "Father absent, family dependent on public assistance"[15]

Results: “The father-present group was superior.”[15]

This further exemplifies the importance of a father being present for the cognitive development of the child.

Also, an income and poverty deficit will have negative influences on the child as well. It is said that “the child poverty increase of recent years is due mainly to a single factor – the retreat of fathers from the lives of their children.”[14] Also, the chance of fatherless children living in poverty “is five times greater than that of children growing up in intact families.”[14] These low income levels impact the education of children in these single-household families. Most families that have a low-income from a single parent has a higher risk of their children going to “lower-quality schools, to live in lower-income communities with fewer educational resources, to have fewer after-school lessons and extracurricular activities, and to have lower educational aspirations.”[14] All of these factors can correlate to a lesser chance of a college education and a lower chance for a positively impactful external society. These situations affect the child in the present situation, but also impact their future life on their own.

Norwegian

The study by David B. Lynn and William L. Sawrey identifies how Norwegian boys and girls are affected by their fathers being absent during wartime. They focus specifically on father's who were absent from sailing in the war.

They took “80 mother-child pairs from several neighboring small towns and their environs in a typical sailor district in Norway.”[16] Half of the 80 mother-child pairs had father-present families and the other 40 had father-absent families. The father-absent group had to have an absent-father for longer than 8 months at a time. All of the participants went through interviews that asked about the family dynamic, including being asked to recreate a drawing of their household.

Findings in the Study:

· “father-absent boys would show more immaturity that the control boys”[16]

· Father-absent boys had stronger “strivings for father-identification.”[16]

· “A significantly higher proportion of father-absent than control boys showed poor peer judgment.”[16] The boys that were fatherless were more affected by this peer choice than the females.

· “Father-absent boys were not as firmly identified with masculinity as were control boys.”

· When the female sex doesn’t have a male father figure they “continue to progress toward psychological maturity” because they gave “increased dependency on the mother.”[16]

These results reflect a more social evaluation of Norwegian boys and girls due to fatherlessness. It underlines the fact that male children not having a father creates them to have a lack of identification with themselves. They tend to do more searching for identification of masculinity than actually creating their own personal achievements. They grow up in confusion and must search on their own to find their niche.

As for fatherless Norwegian girls, they do less searching for their selves due to their same sex parent still being in the household. They are highly attached to mothers because they are feared for their absence; however, their developments aren’t as altered because their identity isn’t being questioned.

Study with British Children

Study by: Douglas, Ross, and Simpson

Who: “3,526 British children born in 1946 tested at ages 8,11, and 15”[17]

Family life of the different groups:

· "165 father absent due to death"[17]

· "118 father consistently away from home versus both parents present"[17]

Results: The scores of children that correlated with the fathers being absent (but not dead) “consistently deteriorated" .16 SD units for girls and .14 for boys between ages 8 and 15.”[17] The children that had a father die were not affected if the father did not die from a “prolonged illness.”[17] This shows that father-absentness had an effect on the children.

Father-infant bonding (Aka father bonding vs. American father bonding)

Infants can become attached to their fathers. Mother-infant bonding has been a common focus in household research; however, “an increasing number of studies in the United States and Europe have tried to understand if and when infants become attached to fathers.”[18] After psychological studies were done it was shown that infants do create a bond with their fathers “and that the infants become attached to fathers at about the same age as they do to mothers (8-10 months of age)”.[18] The ways in which this bonding occurs has been questioned due to different roles fathers have in various cultures. Questions arise about how fathers have the ability to bond with children if they do not have the same kind of role that mothers do in the baby’s development.

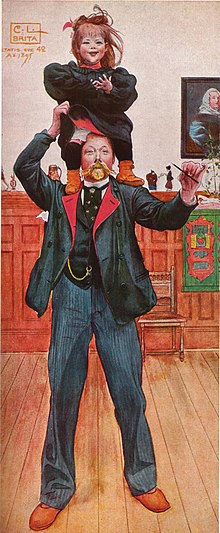

American/European father-infant bonding

European and American fathers are seen to have more of an aggressive and vigorous relationship with their child. This doesn’t mean harmful; however, it means there is physical and “highly stimulating” interaction between the father and child.[18] This gave the child emotions that reflected an exhilarating and fun-loving experience that allowed them to create a father-infant bond different than a mother-infant bond. It is shown that “an infant by two or three weeks displays an entirely different attitude (more wide-eyed, playful, and bright-faced) toward his father than to his mother.”[19] This shows that a father being present gives the child a variety in the way they interact with different people. The rough housing doesn’t just have importance towards the bonds the children make with the father, but also helps to teach them life lessons. Rough play helps to teach “self control”, helps “children learn how to express and appropriately manage their emotions, recognize others’ emotional cues, and understand that biting, kicking, and other forms of physical violence are not acceptable.”[19] This form of bonding between the father and infant creates a bond that is unique. It allows the child to learn valuable lessons, while also being in an environment that enhances all of their senses and allows them to intensify their relationship with their father.

Aka father-infant bonding

The Aka’s are a hunter gatherer society “in the tropical rainforest of southern Central African Republic and northern Congo-Brazzaville.”[18] The was they form their father-infant bond is very different than that of the Europeans and Americans. While Europeans and Americans focus on rough playing, the Aka’s “rarely, if ever, engage in vigorous play with their infants.”[18] Aka fathers are always around their infants when they are born. They always sleep with their infants and are “within an arm’s reach of” them for “more than 50% of 24-hour periods.”[18] Overall, Aka fathers “have a much more intimate role in infant care than fathers in the United States.”[20]

The four factors that are key for Aka father-infant bonding:

1. “Familiarity with the infant”[18]

· Aka fathers are around the child more than most cultures. They hold the child often; therefore, they learn important signs the child shows that most fathers would not. For example, they know “early signs of infant hunger, fatigue, and illness.”[18]

2. “Knowledge of caregiving practices”[18]

· Fathers understand when to be more playful, when to be more physical, how to correctly “hold and infant”, and “how to soothe an infant.”[18] They understand all of the interactions that are needed in taking good care of a child.

3. “The degree of relatedness to the infant”[18]

· The father understands how to make a bond with the infant. They know if the infant needs more rough play or soothing. They play large roles in caretaking, so they understand the infants needs at another level.

4. “Cultural values and parental goals”[18]

· The Aka’s are “gathering-hunting population”; therefore, animal hunting is not a sufficient or main way that they obtain food.[18] This means that the males do not play a large and main role in going out and hunting for the tribe or their own families. This allows the father to be able to spend more time with the infant and really create a bond with them. This makes a father’s role in child upbringing an important aspect of the Aka culture.

The Aka foragers in the Central African Republic do not hunt with bows. Their main source of hunting is through nets. In Hillary N. Fouts cross-cultural research, she had statistical data that supported the claim that different roles in foraging populations had an impact on the amount of time a father spent with their children. Fouts took different foraging populations in Africa and compared their type of hunting and the percentage of time these fathers were seen holding their child. Her first foraging group was the Aka population. They were a “net hunting” group that held their children aged 1-4 months 22% of the day, held their children 8-12 months 11.2% of the day, and held their children 13-18 months 14.3% of the day.[20] The other “net hunting” population was the Bofi.[20] They had fathers hold babies aged from 36-47 and 48-59 months for 5.4% of the day.[20]

In contrast, the foraging groups that participated in “bow hunting” had fathers hold babies for significantly less time.[20] The Hadza foraging population had fathers hold babies from the ages 0-9 months for only 2.5% of the day. The other “bow hunting” foragers, the !Kung, had fathers hold babies from 0-6 months for 1.9% of the day and babies 6-24 months 4.0% of the day.[20]

This statistical data shows that different roles in a society influences how much time the father spends holding and interacting with his children. This is important because it shows that each culture is different regarding father upbringings.

Determination of parenthood

Roman law defined fatherhood as "Mater semper certa; pater est quem nuptiae demonstrant" ("The [identity of the] mother is always certain; the father is whom the marriage vows indicate"). The recent emergence of accurate scientific testing, particularly DNA testing, has resulted in the family law relating to fatherhood experiencing rapid changes.

History of fatherhood

The link between sexual acts and procreation can be empirically identified, but is not immediately evident. Conception cannot be directly observed, whereas birth is obvious. The extended time between the two events makes it difficult to establish the link between them. It is theorised that some cultures have ignored that males impregnate females.[21] Procreation was sometimes even considered to be an autonomous 'ability' of women: men were essential to ensure the survival and defence of the social group, but only women could enhance and reintegrate it through their ability to create new individuals. This gave women a role of primary and indisputable importance within their social groups.[22][23]

This situation may have persisted throughout the Palaeolithic age. Some scholars assert that Venus figurines are evidence of this. During the transition to the Neolithic age, agriculture and cattle breeding became the core activities of a growing number of human communities. Breeding, in particular, is likely to have led women – who used to spend more time than men taking care of the cattle – to gradually discover the procreative effect of the sexual act between a male and a female.[24]

For communities which looked at sexuality as simply a source of pleasure and an element of social cohesion, without any taboo character, this discovery must have led to some disruption.[25] This would impact not only regulation of sexuality, but the whole political, social, and economic system. The shift in understanding would have necessarily taken a long time, but this would not have prevented the implications being relatively dramatic.[23] Eventually, these implications led to the model of society which – in different times and shapes – was adopted by most human cultures.

Traditionally, caring for children is predominantly the domain of mothers, whereas fathers in many societies provide for the family as a whole. Since the 1950s, social scientists and feminists have increasingly challenged gender roles, including that of the male breadwinner. Policies are increasingly targeting fatherhood as a tool of changing gender relations.[26]

Canadian Fatherhood in the Interwar Era

Fatherhood in Canada during the Interwar Period was a time of imposed change, led by state and expert advisement. A response to the impact of World War I on the male population, the Canadian government and citizens attempted to establish a “normalcy” of the family model which consisted of the stay-at-home mother and the breadwinner father as the ideal parental model.[27] The challenge of this established normalcy was that few Canadians outside of the urban middle-class had ever seen this model in their households. Also, advice that was given to fathers at this time without sufficient recommendations on how to implement the standards of good fatherhood. Furthermore, expectations on fathers; and the actual practices of fathers were often different.

World War I's impact on fathers and fathers to be was devastating. Approximately 650,000 Canadian men served in the Armed Forces, and approximately 60,000 were killed, with another 60,000 bearing physical disabilities as a result of injuries. In this time period, very few programs or systems of support existed to help soldiers returning home. Because of this, many survivors of the War turned to drinking, distanced themselves from their families and lashed out at loved ones.

In response to this, government, academic and private institutions brought in experts in medicine, psychology, social work and education with the purpose of establishing a standard of good fathering. This advice was tailored to Anglo-Canadian working-class fathers, but was not written exclusively for them.[28] According to these experts, a father was someone who was the main economic provider of the family, athletic, moral, devoted a portion of his time to his children and was a good husband to his wife.[29] The expectation for fathers’ roles in the lives of their children was to be the authoritative figure of the household who showed love to his family by devoting the majority of his efforts to working and providing financially.[30] A good father was also deemed to be someone who would bring other experts into the process of childrearing, including doctors, nurses, social workers and teachers.[31]

Fathers were also expected to devote a period of time towards their children. Fathers were recommended to spend one hour per week with their sons.[32] Most advice was directed towards the relationship between a father and his son, which encouraged temperance of a father’s response to questions[33] and spending time with boys playing with and coaching them in sports.[34] This amount of time was recognized to be short, but it was deemed better than not spending time with their children at all. Many labour organizations also argued for shorter work weeks as a means of increasing “family time,” for working-class fathers.[35] Many fathers were unable to increase time spent with their children though due to long work days and work weeks.

Although expectations were high for fathers to be the breadwinners for their family, the economic nature of Canada and lack of support often led to differing results. The job market in the Great Depression often did not allow for fathers to provide for their families on a single income[36] and receiving government assistance was seen as a 'personal failure' by many fathers. Since the identity of a father was so rooted in his ability to match the breadwinner model, the inability for a father to provide financially meant that many father's identities as successful members of the family were challenged.[37] Also, although there was an expectation that fathers should be more gentle and temperate towards their children, fathers were often feared by their children.

Patricide

In early human history there have been notable instances of patricide. For example:

- Tukulti-Ninurta I (r. 1243–1207 B.C.E.), Assyrian king, was killed by his own son after sacking Babylon.

- Sennacherib (r. 704–681 B.C.E.), Assyrian king, was killed by two of his sons for his desecration of Babylon.

- King Kassapa I (473 to 495 CE) creator of the Sigiriya citadel of ancient Sri Lanka killed his father king Dhatusena for the throne.

- Emperor Yang of Sui in Chinese history allegedly killed his father, Emperor Wen of Sui.

- Beatrice Cenci, Italian noblewoman who, according to legend, killed her father after he imprisoned and raped her. She was condemned and beheaded for the crime along with her brother and her stepmother in 1599.

- Lizzie Borden (1860–1927) allegedly killed her father and her stepmother with an axe in Fall River, Massachusetts, in 1892. She was acquitted, but her innocence is still disputed.

- Iyasus I of Ethiopia (1682–1706), one of the great warrior emperors of Ethiopia, was deposed by his son Tekle Haymanot in 1706 and subsequently assassinated.

In more contemporary history there have also been instances of father–offspring conflicts, such as:

- Chiyo Aizawa murdered her own father who had been raping her for fifteen years, on October 5, 1968, in Japan. The incident changed the Criminal Code of Japan regarding patricide.

- Kip Kinkel (1982- ), an Oregon boy who was convicted of killing his parents at home and two fellow students at school on May 20, 1998.

- Sarah Marie Johnson (1987- ), an Idaho girl who was convicted of killing both parents on the morning of September 2, 2003.

- Dipendra of Nepal (1971–2001) reportedly massacred much of his family at a royal dinner on June 1, 2001, including his father King Birendra, mother, brother, and sister.

- Christopher Porco (1983- ), was convicted on August 10, 2006, of the murder of his father and attempted murder of his mother with an axe.

Terminology

Biological fathers

- Baby Daddy – A biological father who bears financial responsibility for a child, but with whom the mother has little or no contact.

- Birth father – the biological father of a child who, due to adoption or parental separation, does not raise the child or cannot take care of one.

- Biological father – or just "Father" is the genetic father of a child

- Posthumous father – father died before children were born (or even conceived in the case of artificial insemination)

- Putative father – unwed man whose legal relationship to a child has not been established but who is alleged to be or claims that he may be the biological father of a child

- Sperm donor – an anonymous or known biological father who provides his sperm to be used in artificial insemination or in vitro fertilisation in order to father a child for a third party female. Also used as a slang term meaning "baby daddy".

- Surprise father – where the men did not know that there was a child until possibly years afterward

- Teenage father/youthful father – Father who is still a teenager.

Non-biological (social and legal relationship)

- Adoptive father – the father who has adopted a child

- Cuckolded father – where the child is the product of the mother's adulterous relationship

- DI Dad – social/legal father of children produced via Donor Insemination (where a donor's sperm were used to impregnate the DI Dad's spouse)

- Father-in-law – the father of one's spouse

- Foster father – child is raised by a man who is not the biological or adoptive father usually as part of a couple.

- Mother's partner – assumption that current partner fills father role

- Mother's husband – under some jurisdictions (e.g. in Quebec civil law), if the mother is married to another man, the latter will be defined as the father

- Presumed father – Where a presumption of paternity has determined that a man is a child's father regardless of if he actually is or is not the biological father

- Social father – where a man takes de facto responsibility for a child, such as caring for one who has been abandoned or orphaned (the child is known as a "child of the family" in English law)

- Stepfather – a married non-biological father where the child is from a previous relationship

Fatherhood defined by contact level

- Absent father – father who cannot or will not spend time with his child(ren)

- Second father – a non-parent whose contact and support is robust enough that near parental bond occurs (often used for older male siblings who significantly aid in raising a child)

- Stay-at-home dad – the male equivalent of a housewife with child, where his spouse is breadwinner

- Weekend/holiday father – where child(ren) only stay(s) with father on weekends, holidays, etc.

Non-human fatherhood

For some animals, it is the fathers who take care of the young.

- Darwin's frog (Rhinoderma darwini) fathers carry eggs in the vocal pouch.

- Most male waterfowls are very protective in raising their offspring, sharing scout duties with the female. Examples are the geese, swans, gulls, loons, and a few species of ducks. When the families of most of these waterfowls travel, they usually travel in a line and the fathers are usually the ones guarding the offspring at the end of the line while the mothers lead the way.

- The female seahorse (hippocampus) deposits eggs into the pouch on the male's abdomen. The male releases sperm into the pouch, fertilizing the eggs. The embryos develop within the male's pouch, nourished by their individual yolk sacs.

- Male catfish keep their eggs in their mouth, foregoing eating until they hatch.

- Male emperor penguins alone incubate their eggs; females do no incubation. Rather than building a nest, each male protects his egg by balancing it on the tops of his feet, enclosed in a special brood pouch. Once the eggs are hatched however, the females will rejoin the family.

- Male beavers secure their offspring along with the females during their first few hours of their lives. As the young beavers mature, their fathers will teach them how to search for materials to build and repair their own dams, before they disperse to find their own mates.

- Wolf fathers help feed, protect, and play with their pups. In some cases, several generations of wolves live in the pack, giving pups the care of grandparents, aunts/uncles, and siblings, in addition to parents. The father wolf is also the one who does most of the hunting when the females are securing their newborn pups.

- Coyotes are monogamous and male coyotes hunt and bring food to their young.

- Dolphin fathers help in the care of the young. Newborns are held on the surface of the water by both parents until they are ready to swim on their own.

- A number of bird species have active, caring fathers who assist the mothers, such as the waterfowls mentioned above.

- Apart from humans, fathers in few primate species care for their young. Those that do are tamarins and marmosets.[38] Particularly strong care is also shown by siamangs where fathers carry infants after their second year.[38] In titi and owl monkeys fathers carry their infants 90% of the time with "titi monkey infants developing a preference for their fathers over their mothers".[39] Silverback gorillas have less role in the families but most of them serve as an extra protecting the families from harm and sometimes approaching enemies to distract them so that his family can escape unnoticed.

Many species,[citation needed] though, display little or no paternal role in caring for offspring. The male leaves the female soon after mating and long before any offspring are born. It is the females who must do all the work of caring for the young.

- A male bear leaves the female shortly after mating and will kill and sometimes eat any bear cub he comes across, even if the cub is his. Bear mothers spend much of their cubs' early life protecting them from males. (Many artistic works, such as advertisements and cartoons, depict kindly "papa bears" when this is the exact opposite of reality.)

- Domesticated dog fathers show little interest in their offspring, and unlike wolves, are not monogamous with their mates and are thus likely to leave them after mating.

- Male lions will tolerate cubs, but only allow them to eat meat from dead prey after they have had their fill. A few are quite cruel towards their young and may hurt or kill them with little provocation.[citation needed] A male who kills another male to take control of his pride will also usually kill any cubs belonging to that competing male. However, it is also the males who are responsible for guarding the pride while the females hunt. However the male lions are the only felines that actually have a role in fatherhood.

- Male rabbits generally tolerate kits but unlike the females, they often show little interest in the kits and are known to play rough with their offspring when they are mature, especially towards their sons. This behaviour may also be part of an instinct to drive the young males away to prevent incest matings between the siblings. The females will eventually disperse from the warren as soon as they mature but the father does not drive them off like he normally does to the males.

- Horse stallions and pig boars have little to no role in parenting, nor are they monogamous with their mates. They will tolerate young to a certain extent, but due to their aggressive male nature, they are generally annoyed by the energetic exuberance of the young, and may hurt or even kill the young. Thus, stud stallions and boars are not kept in the same pen as their young or other females.

Finally, in some species neither the father nor the mother provides any care.

See also

- Putative father

- Paternal bond

- Putative father registry

- Sociology of fatherhood

- Responsible fatherhood

- Father complex

- Fathers' rights movement

- Paternal age effect

- Patricide

- Shared Earning/Shared Parenting Marriage

- "Father" can also refer metaphorically to a person who is considered the founder of a body of knowledge or of an institution. In such context the meaning of "father" is similar to that of "founder". See List of persons considered father or mother of a field.

References

- ^ HUMAN GENETICS, MENDELIAN INHERITANCE retrieved 25 February 2012

- ^ What is paternity leave?

- ^ Mapped: Paid paternity leave across the EU...which countries are the most generous? Published by The Telegraph, 18 April 2016

- ^ Fathers 4 Justice take their fight for rights across the Atlantic Published by The Telegraph, 8 May 2005

- ^ One in 50 British fathers unknowingly raises another man's child Published by The Telegraph, April 6, 2016

- ^ Garfield, CF, Clark-Kauffman, K, David, MM; Clark-Kauffman; Davis (Nov 15, 2006). "Fatherhood as a Component of Men's Health". Journal of the American Medical Association. 19 (19): 2365. doi:10.1001/jama.296.19.2365.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Facts for Features". Archived from the original on April 24, 2013. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f 1932-, Popenoe, David, (1996). Life without father : compelling new evidence that fatherhood and marriage are indispensable for the good of children and society. New York: Martin Kessler Books. ISBN 0684822970. OCLC 33359622.

{{cite book}}:|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Children Who Have An Active Father Figure Have Fewer Psychological And Behavioral Problems

- ^ United States. National Center for Fathering, Kansas City, MO. Partnership for Family Involvement in Education. A Call to Commitment: Fathers' Involvement in Children's Learning. June 2000

- ^ Golombok, S; Tasker, F; Murray, C. "Children raised in fatherless families from infancy: family relationships and the socioemotional development of children of lesbian and single heterosexual mothers". J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 38: 783–91. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01596.x. PMID 9363577.

- ^ Children raised in fatherless families from infancy: a follow-up of children of lesbian and single heterosexual mothers at early adolescence

- ^ Ribak, Rivka (2001). ""Like immigrants": negotiating power in the face of the home computer". New media & society. 3 (2): 220–238. doi:10.1177/1461444801003002005.

- ^ a b c d e f 1932-, Popenoe, David, (1996). Life without father : compelling new evidence that fatherhood and marriage are indispensable for the good of children and society. New York: Martin Kessler Books. ISBN 0684822970. OCLC 33359622.

{{cite book}}:|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Shinn, Marybeth (1978). "Father absence and children's cognitive development". Psychological Bulletin. 85 (2): 295–324. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.85.2.295. ISSN 1939-1455.

- ^ a b c d e Lynn, David B.; Sawrey, William L. (1959). "The effects of father-absence on Norwegian boys and girls". The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 59 (2): 258–262. doi:10.1037/h0040784. ISSN 0096-851X.

- ^ a b c d e Shinn, Marybeth (1978). "Father absence and children's cognitive development". Psychological Bulletin. 85 (2): 295–324. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.85.2.295. ISSN 1939-1455.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Gender in cross-cultural perspective. Brettell, Caroline,, Sargent, Carolyn F., 1947- (Seventh edition ed.). Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN 9780415783866. OCLC 962171839.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b D., Parke, Ross (1999). Throwaway dads : the myths and barriers that keep men from being the fathers they want to be. Brott, Armin A. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0395860415. OCLC 39695693.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f Fouts, Hillary N. (2008-04-16). "Father Involvement With Young Children Among the Aka and Bofi Foragers". Cross-Cultural Research. 42 (3): 290–312. doi:10.1177/1069397108317484. ISSN 1069-3971.

- ^ James George Frazer, The Golden Bough, vol. 5-6, Robarts, Toronto, 1914

- ^ Jean Markale, La femme Celt/Women of the Celts, Paris, London, New York, 1972

- ^ a b Jean Przyluski, La Grande Déesse, Payot, Paris, 1950

- ^ Jacques Dupuis, Au nome du pére. Une histoire de la paternité, Lo Rocher, 1987

- ^ Margaret Mead, Male and female, William Morrow & C., New York, 1949

- ^ Bjørnholt, M. (2014). "Changing men, changing times; fathers and sons from an experimental gender equality study" (PDF). The Sociological Review. 62 (2): 295–315. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.12156.

- ^ Commachio, Cynthia 'A Postscript for Father': Defining a New Fatherhood in Interwar Canada, Canadian Historical Review 78, September 1997, pg. 391

- ^ Edwards, An Old-Fashioned Father, Maclean's, 1 March 1934, 22

- ^ Pines, We Want Perfect Parents, Chanteline, Sept. 1928, 31; Dr W.S. Hall, The Family and Family Life, Canadian Mentor 7, 1925.

- ^ Blatz, W.E. Bott, H.M, Parents and the Preschool Child Toronto: J.M. Dent 1928, pg. 224-5

- ^ MacMurchy, Mother Ottawa: King's Printer, 1928, pg. 15-16,

- ^ Letters from a Schoolmaster, Maclean's, 15 April 1938, 43

- ^ Letters from a Schoolmaster, Maclean's, 15 Feb. 1938,

- ^ Commachio, "A Postscript for Fathers," pg. 404

- ^ Palmer, B. and Kealey, G. Dreaming of What Might Be: The Knights of Labour in Ontario Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1982, 318;

- ^ Changes in the Cost of Living in Canada from 1913 to 1937, Labour Gazette, June 1937, pg. 819-21

- ^ Commachio, Cynthia 'A Postscript for Father': Defining a New Fatherhood in Interwar Canada, Canadian Historical Review 78, September 1997, pg. 394

- ^ a b Fernandez-Duque, E; Valeggia, CR; Mendoza, SP (2009). "Biology of Paternal Care in Human and Nonhuman Primates". Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 38: 115–30. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-091908-164334.

- ^ Mendoza, SP; Mason, WA (1986). "Parental division of labour and differentiation of attachments in a monogamous primate (Callicebus moloch)". Anim. Behav. 34: 1336–47. doi:10.1016/s0003-3472(86)80205-6.

Bibliography

- Inhorn, Marcia C.; Chavkin, Wendy; Navarro, José-Alberto, eds. (2015). Globalized fatherhood. New York: Berghahn. ISBN 9781782384373. Studies by anthropologists, sociologists, and cultural geographers -

- Kraemer, Sebastian (1991). "The Origins of Fatherhood: An Ancient Family Process". Family Process. 30 (4): 377–392. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.1991.00377.x. PMID 1790784.

- Diamond, Michael J. (2007). My father before me : how fathers and sons influence each other throughout their lives. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 9780393060607.

- Collier, Richard (2013). "Rethinking men and masculinities in the contemporary legal profession: the example of fatherhood, transnational business masculinities, and work-life balance in large law firms". Nevada Law Journal, special issue: Men, Masculinities, and Law: A Symposium on Multidimensional Masculinities Theory. 13 (2). William S. Boyd School of Law: 7.