Azerbaijanis in Armenia: Difference between revisions

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

:{{see also|Deportation of Azerbaijanis from Armenia}} |

:{{see also|Deportation of Azerbaijanis from Armenia}} |

||

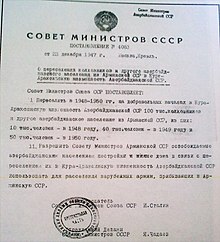

[[File:1348221380 o-pereselenii-iz-zangezura.jpg|thumb|Stalin signed decree ordering deportation of Azerbaijanis from Armenian SSR and replacement of foreign Armenians in their houses in December 23, 1947]] |

|||

For Azeris of Armenia, the twentieth century was the period of marginalization, discrimination, mass and often forcible migrations<ref name="dewaal">Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War by Thomas de Waal ISBN 0-8147-1945-7</ref> resulting in significant changes in the country's ethnic composition, even though they had managed to stay its largest ethnic minority until the [[Nagorno-Karabakh conflict]]. In 1905–1907 Erivan Governorate became an arena of clashes between Armenians and Azeris believed to have been instigated by the Russian government in order to draw public attention away from the [[Russian Revolution of 1905]].<ref>{{ru icon}} [http://www.dk1868.ru/history/ZAKAVKAZ.htm Memories of the Revolution in Transcaucasia] by Boris Baykov</ref> |

For Azeris of Armenia, the twentieth century was the period of marginalization, discrimination, mass and often forcible migrations<ref name="dewaal">Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War by Thomas de Waal ISBN 0-8147-1945-7</ref> resulting in significant changes in the country's ethnic composition, even though they had managed to stay its largest ethnic minority until the [[Nagorno-Karabakh conflict]]. In 1905–1907 Erivan Governorate became an arena of clashes between Armenians and Azeris believed to have been instigated by the Russian government in order to draw public attention away from the [[Russian Revolution of 1905]].<ref>{{ru icon}} [http://www.dk1868.ru/history/ZAKAVKAZ.htm Memories of the Revolution in Transcaucasia] by Boris Baykov</ref> |

||

Revision as of 14:28, 23 February 2013

The Azerbaijanis in Armenia (Azerbaijani: Ermənistan azərbaycanlıları) were the largest ethnic minority, but have been virtually non-existent since in 1988–1991 when most Azerbaijanis fled the country as a result of the Nagorno-Karabakh War and the ongoing conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan. UNHCR estimates the current population of Azeris in Armenia to be somewhere between 30 and a few hundred persons,[1] with majority of them living in rural areas and being members of mixed couples (mostly mixed marriages), as well as elderly and sick. Most of them are also reported to have changed their names and maintain a low profile to avoid discrimination.[2][3]

History

Upon Seljuk conquests in tenth century, the mass of the Oghuz Turkic tribes who crossed the Amu Darya towards the west left the Iranian plateau, which remained Persian, and established themselves more to the west, in Armenia the Caucasus and Anatolia. Here they divided into Ottomans, who were Sunni and settled, and Turkmens who were nomads and in part Shiite.

After centuries of constant warfare on the Armenian Plateau, many Armenians chose to emigrate and settle elsewhere. Following Shah Abbas I's massive relocation of Armenians and Muslims in 1604-05,[4] their numbers began to decrease gradually, eventually leading them to a minority among their Muslim neighbours.[5] According to the Armenian-American historian George Bournoutian:[6][page needed]

In the first quarter of the 19th century the Khanate of Erevan included most of Eastern Armenia and covered an area of approximately 7,000 square miles. The land was mountainous and dry, the population of about 100,000 was roughly 80 percent Muslim and 20 percent Christian (Armenian)

After the incorporation of the Erivan khanate into the Russian Empire in 1828, many Muslims left the area and were replaced with the tens of thousands of Armenian refugees from Persia.[7][8] By 1832 Muslims in what had been the Erivan khanate were already outnumbered by the immigrating Armenians.[9] According to the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, by the beginning of the twentieth century a significant population of Azeris still lived in Russian Armenia. They numbered about 300,000 persons or 37.5% in Russia's Erivan Governorate (roughly corresponding to most of present-day central Armenia, the Iğdır Province of Turkey, and Azerbaijan's Nakhchivan exclave).[10]

Most lived in rural areas and were engaged in farming and carpet-weaving. They formed the majority in 4 of the governorate's 7 districts, including the city of Erivan (Yerevan) itself where they constituted 49% of the population (compared to 48% constituted by Armenians).[11] At the time, Eastern Armenian cultural life was centered more around the holy city of Echmiadzin, seat of the Armenian Apostolic Church.[12] Traditionally Azeris in Armenia were almost entirely Shia Muslim, with the exception of the Talin region, as well as small pockets in Shorayal and around Vedi where they mainly adhered to Sunni Islam.[13] Traveller Luigi Villari reported in 1905 that in Erivan the Azeris (to whom he referred as Tartars) were generally wealthier than the Armenians, and owned nearly all of the land.[14]

-

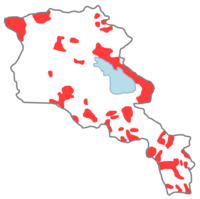

Distribution of Azerbaijanis in modern borders of Armenia, 1896-1890.

-

Distribution of Azerbaijanis in the Armenian SSR, 1926.

-

Distribution of Azerbaijanis in the Armenian SSR, 1962.

For Azeris of Armenia, the twentieth century was the period of marginalization, discrimination, mass and often forcible migrations[15] resulting in significant changes in the country's ethnic composition, even though they had managed to stay its largest ethnic minority until the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. In 1905–1907 Erivan Governorate became an arena of clashes between Armenians and Azeris believed to have been instigated by the Russian government in order to draw public attention away from the Russian Revolution of 1905.[16]

Tensions rose again after both Armenia and Azerbaijan became briefly independent from the Russian Empire in 1918. Both quarreled over where their common borders lay.[12] Warfare coupled with the influx of Armenian refugees resulted in widespread massacres of Muslims in Armenia[17][18][19][20][21] causing virtually all of them to flee to Azerbaijan.[15] Andranik Ozanian and Rouben Ter Minassian were particularly prominent in the destruction of Muslim settlements and in the planned ethnic homogenisation of regions with once mixed population through populating them with Armenian refugees from Turkey.[22] Relatively few of the evicted Azeris returned, as according to the 1926 All-Soviet population census there were only 78,228 Azeris living in Armenia, comprising 8.8% of the population.[23] By 1939 their numbers had increased to 131,000.[24]

In 1947, Grigory Arutyunov, then First Secretary of the Communist Party of Armenia, managed to persuade the Council of Ministers of the USSR to issue a decree entitled Planned measures for the resettlement of collective farm workers and other Azerbaijanis from the Armenian SSR to the Kura-Arax lowlands of the Azerbaijani SSR.[25] According to the decree, between 1948 and 1951, the Azeri community in Armenia became partly subject to a "voluntary resettlement" (called by some sources a deportation[26][27][28]) to central Azerbaijan[29] to make way for Armenian immigrants from the Armenian diaspora. In those four years some 100,000 Azeris were deported from Armenia.[23] This reduced the number of those in Armenia down to 107,748 in 1959.[30] By 1979, Azeris numbered 160,841 and constituted 5.3% of Armenia's population.[31] The Azeri population of Yerevan, that once formed the majority, dropped to 0.7% by 1959 and further to 0.1% by 1989.[27]

Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

| Part of a series on |

| Azerbaijanis |

|---|

| Culture |

| Traditional areas of settlement |

| Diaspora |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Persecution |

When the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict broke out as the Soviet Union was falling apart Armenia had a large Azeri population.[32] Civil unrest in Nagorno-Karabakh in 1987 led to Azeris' being often harassed and forced to leave Armenia.[33] On 25 January 1988 the first wave of Azeri refugees from Armenia settled in the city of Sumgait.[33][34] On 23 March, the presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union – that is the highest institution in the Union – rejected the demands of the Nagorno-Karabakh Council of People's Deputies to join Armenia without any possibility of appeal. Troops were deployed in Yerevan to prevent protests to the decision. In the following months, Azeris in Armenia were subject to further harassment and forced to flee. In the district of Ararat, four villages were burned on 25 March. On 7 June, Azeris were evicted from the town of Masis near the Armenian–Turkish border, and on the 20th of the same month five more Azeri villages were cleansed in the Ararat region.[35] Another major wave occurred in November 1988[34] as Azeris were either expelled by the nationalists and local or state authorities,[36] or fled fearing for their lives.[2] Violence took place as a result of ethnic conflicts;[37] in November 1988, 25 Azeris were killed, according to Armenian sources (of those 20 in the town of Gugark);[38] and 217, according to Azerbaijani sources.[39]

Thus, in 1988–91 the remaining Azeris were forced to flee primarily to Azerbaijan.[36][40][41] It is impossible to determine the exact population numbers for Azeris in Armenia at the time of the conflict's escalation, since during the 1989 census forced Azeri migration from Armenia was already in progress. UNHCR's estimate is 200,000 persons.[2]

Current situation

With the departure of Azeris, not only did the Azeri cultural life in Armenia cease to exist, but its traces were being vigorously written out of history, according to journalist Thomas de Waal. In 1990 a mosque located on Vardanants Street was demolished by a bulldozer.[42] Another Islamic site, the Blue Mosque (where most of the worshippers had been Azeri since the 1760s) has since been often referred to as the "Persian mosque" intending to rid Armenia of the Azeri trace by a "linguistic sleight of hand," according to de Waal.[43] Geographical names of Turkic origin were changed en masse into Armenian-sounding ones,[44] (in addition to those continuously changed from the 1930s on[23]) a measure seen by some as a method to erase from popular memory the fact that Muslims had once formed a substantial portion of the local population.[45]

Some Azeris continue to live in Armenia to the current-day. Hranoush Kharatyan, the head of Department on National Minorities and Religion Matters of Armenia, stated in February 2007:

Yes, ethnic Azerbaijanis are living in Armenia. I know many of them but I can't give numbers. Armenia has signed a UN convention according to which the states take an obligation not to publish statistical data related to groups under threat or who consider themselves to be under threat if these groups are not numerous and might face problems. During the census, a number of people described their ethnicity as Azerbaijani. I know some Azerbaijanis who came here with their wives or husbands. Some prefer not to speak out about their ethnic affiliation; others take it more easily. We spoke with some known Azerbaijanis residing in Armenia but they haven't manifested a will to form an ethnic community yet.[46]

Prominent Azeris from Armenia

- Ashig Alasgar, 19th century Azeri poet and folk singer

- Mirza Gadim Iravani, Azeri painter of the mid-19th century

- Mammad agha Shahtakhtinski, Azerbaijani linguist and Member of the State Duma

- Akbar agha Sheykhulislamov, Minister of Agriculture of Azerbaijan in 1918–1920

- Heydar Huseynov, Azerbaijani philosopher

- Aziz Aliyev, Soviet politician

- Yahya Rahim Safavi, former Chief Commander of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards

- Said Rustamov, Azerbaijani composer and conductor

- Mirali Seyidov, Azerbaijani philologist

- Mustafa Topchubashov, prominent Soviet surgeon and academician

- Ali Insanov, former Minister of Healthcare of Azerbaijan

- Huseyn Seyidzadeh, Azerbaijani film director

- Ahmad Jamil, Azerbaijani poet

- Ramiz Hasanoglu, Azerbaijani film director

- Ahliman Amiraslanov, Azerbaijani physician

- Misir Mardanov, Minister of Education of Azerbaijan

- Ismat Abbasov, Minister of Agriculture of Azerbaijan

- Mahmud Karimov, current President of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan

- Avaz Alakbarov, Azerbaijani economist, ex-Minister of Finance of Azerbaijan

- Khagani Mammadov, Azerbaijani football player

- Khalaf Khalafov, Deputy Minister of the Foreign Affairs Ministry

- Ramazan Abbasov, Azerbaijani football player

- Rovshan Huseynov, Azerbaijani boxer

- Shahin Mustafayev, Minister of Economic Development of Azerbaijan

- Ogtay Asadov, Speaker of the National Assembly of Azerbaijan

- Hidayat Orujov, Azerbaijani writer and Chairman of the State Committee for Work with Religious Organizations of Azerbaijan Republic

- Garib Mammadov, Chairman of State Land and Cartography Committee of Azerbaijan Republic.

- Zulfi Hajiyev, Deputy Prime Minister of Azerbaijan, Member of Azerbaijani Parliament

- Yusif Yusifov, a prominent Azerbaijani historian, orientalist, linguist, specialist on ancient literature.

See also

References

- ^ Second Report Submitted by Armenia Pursuant to Article 25, Paragraph 1 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities. Received on 24 November 2004

- ^ a b c International Protection Considerations Regarding Armenian Asylum-Seekers and Refugees. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Geneva: September 2003

- ^ Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2003: Armenia U.S. Department of State. Released 25 February 2004

- ^ Arakel of Tabriz. The Books of Histories; chapter 4. Quote: "[The Shah] deep inside understood that he would be unable to resist Sinan Pasha, i.e. the Sardar of Jalaloghlu, in a[n open] battle. Therefore he ordered to relocate the whole population of Armenia - Christians, Jews and Muslims alike, to Persia, so that the Ottomans find the country depopulated."

- ^ Bournoutian, George A. "Eastern Armenia from the Seventeenth Century to the Russian Annexation" in The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century. Ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1997, p. 96.

- ^ George A. Bournoutian. Eastern Armenia in the Last Decades of Persian Rule, 1807-1828 (Malibu: Undena Publications, 1982)

- ^ Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia and South Ossetia: A Legal Appraisal by Tim Potier. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. 2001. p.2 ISBN 90-411-1477-7

- ^ Asian and African Studies by Ḥevrah ha-Mizraḥit ha-Yiśreʾelit. Jerusalem Academic Press., 1987; p. 57

- ^ Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus by Svante Cornell. Routledge. 2001. p.67 ISBN 0-7007-1162-7

- ^ Template:Ru icon Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary: Erivan Governorate

- ^ Template:Ru icon Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary: Erivan

- ^ a b Thomas de Waal. Black Garden: Armenia And Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press, p. 74. ISBN 0-8147-1945-7 Cite error: The named reference "DeWaal01" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ A. Tsutsiyev (2004) (АТЛАС ЭТНОПОЛИТИЧЕСКОЙ ИСТОРИИ КАВКАЗА, Цуциев А.А, Москва: Издательство «Европа», 2007)

- ^ Fire and Sword in the Caucasus by Luigi Villari. London, T. F. Unwin, 1906: p. 267

- ^ a b Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War by Thomas de Waal ISBN 0-8147-1945-7

- ^ Template:Ru icon Memories of the Revolution in Transcaucasia by Boris Baykov

- ^ Modern Hatreds: The Symbolic Politics of Ethnic War by Stuart J. Kaufman. Cornell University Press. 2001. p.58 ISBN 0-8014-8736-6

- ^ Template:Ru icon Turkish-Armenian War of 1920

- ^ Turkish-Armenian War: Sep.24 – Dec.2, 1920 by Andrew Andersen

- ^ Template:Ru icon Ethnic Conflicts in the USSR: 1917–1991. State Archives of the Russian Federation, fund 1318, list 1, folder 413, document 21

- ^ Template:Ru icon Garegin Njdeh and the KGB: Report of Interrogation of Ohannes Hakopovich Devedjian August 28, 1947. Retrieved May 31, 2007

- ^ The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction by Donald Bloxham. Oxford University Press: 2005, pp.103-105

- ^ a b c The Alteration of Place Names and Construction of National Identity in Soviet Armenia by Arseny Sarapov

- ^ Template:Ru iconAll-Soviet Population Census of 1939 - Ethnic Composition in the Republics of the USSR: Armenian SSR. Demoscope.ru

- ^ A Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev by Vladislav Zubok. UNC Press, 2007. ISBN 0-8078-3098-4; p. 58

- ^ Deportation of 1948-1953. Azerbembassy.org.cn

- ^ a b Language Policy in the Soviet Union by Lenore A. Grenoble. Springer: 2003, p.135 ISBN 1-4020-1298-5

- ^ Central Asia: Its Strategic Importance and Future Prospects by Hafeez Malik. St. Martin's Press: 1994, p.149 ISBN 0-312-10370-0

- ^ Armenia: Political and Ethnic Boundaries 1878-1948 by Anita L. P. Burdett (ed.) ISBN 1-85207-955-X

- ^ Template:Ru icon All-Soviet Population Census of 1959 - Ethnic Composition in the Republics of the USSR: Armenian SSR. Demoscope.ru

- ^ Template:Ru icon All-Soviet Population Census of 1979 - Ethnic Composition in the Republics of the USSR: Armenian SSR. Demoscope.ru

- ^ Jewish Post: Jewish Armenia

- ^ a b Template:Ru icon The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict by Svante Cornell. Sakharov-Center.ru

- ^ a b Template:Ru icon Karabakh: Timeline of the Conflict. BBC Russian

- ^ Cornell, Svante E. The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict. Uppsala: Department of East European Studies, April 1999.

- ^ a b After Independence by Lowell W. Barrington. University of Michigan Press, 2006; p. 231. ISBN 0-472-06898-9

- ^ The Unrecognized IV. The Bitter Fruit of the 'Black Garden' by Yazep Abzavaty. Nashe Mnenie. 15 January 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2008

- ^ Template:Ru icon Pogroms in Armenia: Opinions, Conjecture and Facts. Interview with Head of the Armenian Committee for National Security Usik Harutyunyan. Ekspress-Khronika. #16. 16 April 1991. Retrieved 1 August 2008

- ^ Azerbaijan State Commission On Prisoners of War, Hostages and Missing Persons

- ^ UNHCR U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Citizenship and Immigration Services Country Reports Azerbaijan. The Status of Armenians, Russians, Jews and Other Minorities

- ^ Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2004: Armenia. U.S. Department of State

- ^ Myths and Realities of Karabakh War by Thomas de Waal. Caucasus Reporting Service. CRS No. 177, 1 May 2003. Retrieved 31 July 2008

- ^ de Waal, p.80

- ^ Template:Ru icon Renaming Towns in Armenia to Be Concluded in 2007. Newsarmenia.ru. 22

- ^ Nation and Politics in the Soviet Successor States by Ian Bremmer and Ray Taras. Cambridge University Press, 1993; p.270 ISBN 0-521-43281-2

- ^ "The Azerbaijanis Residing in Armenia Don’t Want to Form an Ethnic Community" by Tatul Hakobyan. Hetq.am 26 February 2007

External links

- Armenia and Azerbaijan: The Remaining by Zarema Valikhanova and Marianna Grigoryan

- "I Always Dream of Baku" by Alexei Manvelyan