Cholangiocarcinoma: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 583476682 by 24.0.133.234 (talk) agree - NPOV problems once again |

|||

| Line 178: | Line 178: | ||

* {{cite journal |author=Khan S, Taylor-Robinson S, Toledano M, Beck A, Elliott P, Thomas H |title=Changing international trends in mortality rates for liver, biliary and pancreatic tumours |journal=J Hepatol |volume=37 |issue=6 |pages=806–13 |year=2002 |pmid=12445422 |doi=10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00297-0}} |

* {{cite journal |author=Khan S, Taylor-Robinson S, Toledano M, Beck A, Elliott P, Thomas H |title=Changing international trends in mortality rates for liver, biliary and pancreatic tumours |journal=J Hepatol |volume=37 |issue=6 |pages=806–13 |year=2002 |pmid=12445422 |doi=10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00297-0}} |

||

* {{cite journal |author=Welzel T, McGlynn K, Hsing A, O'Brien T, Pfeiffer R |title=Impact of classification of hilar cholangiocarcinomas (Klatskin tumors) on the incidence of intra- and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States |journal=J Natl Cancer Inst |volume=98 |issue=12 |pages=873–5 |year=2006 |pmid=16788161 |doi=10.1093/jnci/djj234}}</ref> The reasons for the increasing occurrence of cholangiocarcinoma are unclear; improved diagnostic methods may be partially responsible, but the prevalence of potential risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma, such as [[HIV|HIV infection]], has also been increasing during this time frame.<ref name="riskfactors">{{cite journal |author=Shaib Y, El-Serag H, Davila J, Morgan R, McGlynn K |title=Risk factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a case-control study |journal=Gastroenterology |volume=128 |issue=3 |pages=620–6 |year=2005 |pmid=15765398 |doi=10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.048}}</ref> |

* {{cite journal |author=Welzel T, McGlynn K, Hsing A, O'Brien T, Pfeiffer R |title=Impact of classification of hilar cholangiocarcinomas (Klatskin tumors) on the incidence of intra- and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States |journal=J Natl Cancer Inst |volume=98 |issue=12 |pages=873–5 |year=2006 |pmid=16788161 |doi=10.1093/jnci/djj234}}</ref> The reasons for the increasing occurrence of cholangiocarcinoma are unclear; improved diagnostic methods may be partially responsible, but the prevalence of potential risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma, such as [[HIV|HIV infection]], has also been increasing during this time frame.<ref name="riskfactors">{{cite journal |author=Shaib Y, El-Serag H, Davila J, Morgan R, McGlynn K |title=Risk factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a case-control study |journal=Gastroenterology |volume=128 |issue=3 |pages=620–6 |year=2005 |pmid=15765398 |doi=10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.048}}</ref> |

||

==Notable Victims== |

|||

[[Ray Manzarek]], keyboard player of [[The Doors]], died from bile duct cancer. |

|||

[[Tank McNamara|Jeffrey Lynn Millar]], American cartoonist |

|||

[[Walter Payton]], running back, [[Chicago Bears]] |

|||

[[Peter Wintonick]], Documentary Filmmaker |

|||

==Notes== |

==Notes== |

||

Revision as of 02:41, 27 November 2013

| Cholangiocarcinoma | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Oncology |

Cholangiocarcinoma is a medical term denoting a form of cancer that is composed of mutated epithelial cells (or cells showing characteristics of epithelial differentiation) that originate in the bile ducts which drain bile from the liver into the small intestine. Other biliary tract cancers include pancreatic cancer, gallbladder cancer, and cancer of the ampulla of Vater.

Cholangiocarcinoma is a relatively rare neoplasm that is classified as an adenocarcinoma (a cancer that forms glands or secretes significant amounts of mucins). It has an annual incidence rate of 1–2 cases per 100,000 in the Western world,[1] but rates of cholangiocarcinoma have been rising worldwide over the past several decades.[2]

Prominent signs and symptoms of cholangiocarcinoma include abnormal liver function tests, abdominal pain, jaundice, and weight loss. generalized itching, fever, and changes in color of stool or urine may also occur. The disease is diagnosed through a combination of blood tests, imaging, endoscopy, and sometimes surgical exploration, with confirmation obtained after a pathologist examines cells from the tumor under a microscope. Known risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma include primary sclerosing cholangitis (an inflammatory disease of the bile ducts), congenital liver malformations, infection with the parasitic liver flukes Opisthorchis viverrini or Clonorchis sinensis, and exposure to Thorotrast (thorium dioxide), a chemical formerly used in medical imaging. However, most patients with cholangiocarcinoma have no identifiable specific risk factors.

Cholangiocarcinoma is considered to be an incurable and rapidly lethal malignancy unless both the primary tumor and any metastases can be fully resected (removed surgically). No potentially curative treatment yet exists except surgery, but most patients have advanced stage disease at presentation and are inoperable at the time of diagnosis. Patients with cholangiocarcinoma are generally managed - though never cured - with chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and other palliative care measures. These are also used as adjuvant therapies (i.e. post-surgically) in cases where resection has apparently been successful (or nearly so). Some areas of ongoing medical research in cholangiocarcinoma include the use of newer targeted therapies, (such as erlotinib) or photodynamic therapy for treatment, and the techniques to measure the concentration of byproducts of cancer stromal cell formation in the blood for diagnostic purposes.

Staging

Although there are at least three staging systems for cholangiocarcinoma (e.g. those of Bismuth, Blumgart, and the American Joint Committee on Cancer), none have been shown to be useful in predicting survival.[3] The most important staging issue is whether the tumor can be surgically removed, or whether it is too advanced for surgical treatment to be successful. Often, this determination can only be made at the time of surgery.[4]

General guidelines for operability include:[5][6]

- Absence of lymph node or liver metastases

- Absence of involvement of the portal vein

- Absence of direct invasion of adjacent organs

- Absence of widespread metastatic disease

Signs and symptoms

The most common physical indications of cholangiocarcinoma are abnormal liver function tests, jaundice (yellowing of the eyes and skin occurring when bile ducts are blocked by tumor), abdominal pain (30%–50%), generalized itching (66%), weight loss (30%–50%), fever (up to 20%), and changes in stool or urine color.[7][8] To some extent, the symptoms depend upon the location of the tumor: patients with cholangiocarcinoma in the extrahepatic bile ducts (outside the liver) are more likely to have jaundice, while those with tumors of the bile ducts within the liver more often have pain without jaundice.[9]

Blood tests of liver function in patients with cholangiocarcinoma often reveal a so-called "obstructive picture," with elevated bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and gamma glutamyl transferase levels, and relatively normal transaminase levels. Such laboratory findings suggest obstruction of the bile ducts, rather than inflammation or infection of the liver parenchyma, as the primary cause of the jaundice.[4] CA19-9 is elevated in most cases of cholangiocarcinoma.

Risk factors

Although most patients present without any known risk factors evident, a number of risk factors for the development of cholangiocarcinoma have been described. In the Western world, the most common of these is primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), an inflammatory disease of the bile ducts which is itself closely associated with ulcerative colitis (UC).[10] Epidemiologic studies have suggested that the lifetime risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma for a person with PSC is on the order of 10%–15%,[11] although autopsy series have found rates as high as 30% in this population.[12] The mechanism by which PSC increases the risk of cholangiocarcinoma is not well understood.

Certain parasitic liver diseases may be risk factors as well. Colonization with the liver flukes Opisthorchis viverrini (found in Thailand, Laos, and Malaysia) or Clonorchis sinensis (found in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam) has been associated with the development of cholangiocarcinoma.[13][14][15] Patients with chronic liver disease, whether in the form of viral hepatitis (e.g. hepatitis B or hepatitis C),[16][17][18] alcoholic liver disease, or cirrhosis of the liver due to other causes, are at significantly increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma.[19][20] HIV infection was also identified in one study as a potential risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma, although it was unclear whether HIV itself or other correlated and confounding factors (e.g. hepatitis C infection) were responsible for the association.[19]

Congenital liver abnormalities, such as Caroli's syndrome or choledochal cysts, have been associated with an approximately 15% lifetime risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma.[21][22] The rare inherited disorders Lynch syndrome II and biliary papillomatosis have also been found to be associated with cholangiocarcinoma.[23][24] The presence of gallstones (cholelithiasis) is not clearly associated with cholangiocarcinoma. However, intrahepatic stones (called hepatolithiasis), which are rare in the West but common in parts of Asia, have been strongly associated with cholangiocarcinoma.[25][26][27] Exposure to Thorotrast, a form of thorium dioxide which was used as a radiologic contrast medium, has been linked to the development of cholangiocarcinoma as late as 30–40 years after exposure; Thorotrast was banned in the United States in the 1950s due to its carcinogenicity.[28][29]

Pathophysiology

Cholangiocarcinoma can affect any area of the bile ducts, either within or outside the liver. Tumors occurring in the bile ducts within the liver are referred to as intrahepatic, those occurring in the ducts outside the liver are extrahepatic, and tumors occurring at the site where the bile ducts exit the liver may be referred to as perihilar. A cholangiocarcinoma occurring at the junction where the left and right hepatic ducts meet to form the common bile duct may be referred to eponymously as a Klatskin tumor.[30]

Although cholangiocarcinoma is known have the histological and molecular features of an adenocarcinoma of epithelial cells lining the biliary tract, the actual cell of origin is unknown. Recent evidence has suggested that the initial transformed cell that generates the primary tumor may arise from a pluripotent hepatic stem cell.[31][32][33] Cholangiocarcinoma is thought to develop through a series of stages - from early hyperplasia and metaplasia, through dysplasia, to the development of frank carcinoma - in a process similar to that seen in the development of colon cancer.[34] Chronic inflammation and obstruction of the bile ducts, and the resulting impaired bile flow, are thought to play a role in this progression.[34][35][36]

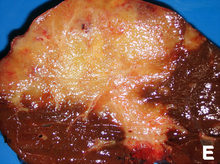

Histologically, cholangiocarcinomas may vary from undifferentiated to well-differentiated. They are often surrounded by a brisk fibrotic or desmoplastic tissue response; in the presence of extensive fibrosis, it can be difficult to distinguish well-differentiated cholangiocarcinoma from normal reactive epithelium. There is no entirely specific immunohistochemical stain that can distinguish malignant from benign biliary ductal tissue, although staining for cytokeratins, carcinoembryonic antigen, and mucins may aid in diagnosis.[37] Most tumors (>90%) are adenocarcinomas.[38]

Diagnosis

Cholangiocarcinoma is definitively diagnosed from tissue, i.e. it is proven by biopsy or examination of the tissue excised at surgery. It may be suspected in a patient with obstructive jaundice. Considering it as the working diagnosis may be challenging in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC); such patients are at high risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma, but the symptoms may be difficult to distinguish from those of PSC. Furthermore, in patients with PSC, such diagnostic clues as a visible mass on imaging or biliary ductal dilatation may not be evident.

Blood tests

There are no specific blood tests that can diagnose cholangiocarcinoma by themselves. Serum levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA19-9 are often elevated, but are not sensitive or specific enough to be used as a general screening tool. However, they may be useful in conjunction with imaging methods in supporting a suspected diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma.[39]

Abdominal imaging

Ultrasound of the liver and biliary tree is often used as the initial imaging modality in patients with suspected obstructive jaundice.[40][41] Ultrasound can identify obstruction and ductal dilatation and, in some cases, may be sufficient to diagnose cholangiocarcinoma.[42] Computed tomography (CT) scanning may also play an important role in the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma.[43][44][45]

Imaging of the biliary tree

While abdominal imaging can be useful in the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma, direct imaging of the bile ducts is often necessary. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), an endoscopic procedure performed by a gastroenterologist or specially trained surgeon, has been widely used for this purpose. Although ERCP is an invasive procedure with attendant risks, its advantages include the ability to obtain biopsies and to place stents or perform other interventions to relieve biliary obstruction.[4] Endoscopic ultrasound can also be performed at the time of ERCP and may increase the accuracy of the biopsy and yield information on lymph node invasion and operability.[46] As an alternative to ERCP, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) may be utilized. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is a non-invasive alternative to ERCP.[47][48][49] Some authors have suggested that MRCP should supplant ERCP in the diagnosis of biliary cancers, as it may more accurately define the tumor and avoids the risks of ERCP.[50][51][52]

Surgery

Surgical exploration may be necessary to obtain a suitable biopsy and to accurately stage a patient with cholangiocarcinoma. Laparoscopy can be used for staging purposes and may avoid the need for a more invasive surgical procedure, such as laparotomy, in some patients.[53][54] Surgery is also the only curative option for cholangiocarcinoma, although it is limited to patients with early-stage disease.

Pathology

Histologically, cholangiocarcinomas are classically well to moderately differentiated adenocarcinomas. Immunohistochemistry is useful in the diagnosis and may be used to help differentiate a cholangiocarcinoma from, hepatocellular carcinoma and metastasis of other gastrointestinal tumors.[55] Cytological scrapings are often nondiagnostic,[56] as these tumors typically have a desmoplastic stroma and, therefore, do not release diagnostic tumor cells with scrapings.

Treatment

Cholangiocarcinoma is considered to be an incurable and rapidly lethal disease unless all the tumors can be fully resected (that is, cut out surgically). Since the operability of the tumor can only be assessed during surgery in most cases,[57] a majority of patients undergo exploratory surgery unless there is already a clear indication that the tumor is inoperable.[4] However, the Mayo Clinic has reported significant success treating early bile duct cancer with liver transplantation using a protocolized approach and strict selection criteria.[58]

Adjuvant therapy followed by liver transplantation may have a role in treatment of certain unresectable cases.[59]

Adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy

If the tumor can be removed surgically, patients may receive adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy after the operation to improve the chances of cure. If the tissue margins are negative (i.e. the tumor has been totally excised), adjuvant therapy is of uncertain benefit. Both positive[60][61] and negative[9][62][63] results have been reported with adjuvant radiation therapy in this setting, and no prospective randomized controlled trials have been conducted as of March 2007. Adjuvant chemotherapy appears to be ineffective in patients with completely resected tumors.[64] The role of combined chemoradiotherapy in this setting is unclear. However, if the tumor tissue margins are positive, indicating that the tumor was not completely removed via surgery, then adjuvant therapy with radiation and possibly chemotherapy is generally recommended based on the available data.[65]

Treatment of advanced disease

The majority of cases of cholangiocarcinoma present as inoperable (unresectable) disease[66] in which case patients are generally treated with palliative chemotherapy, with or without radiotherapy. Chemotherapy has been shown in a randomized controlled trial to improve quality of life and extend survival in patients with inoperable cholangiocarcinoma.[67] There is no single chemotherapy regimen which is universally used, and enrollment in clinical trials is often recommended when possible.[65] Chemotherapy agents used to treat cholangiocarcinoma include 5-fluorouracil with leucovorin,[68] gemcitabine as a single agent,[69] or gemcitabine plus cisplatin,[70] irinotecan,[71] or capecitabine.[72] A small pilot study suggested possible benefit from the tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib in patients with advanced cholangiocarcinoma.[73]

Photodynamic therapy, an experimental approach in which patients are injected with a light-sensitizing agent and light is then applied endoscopically directly to the tumor, has shown promising results compared to supportive care in two small randomized controlled trials. However, its ultimate role in the management of cholangiocarcinoma is unclear at present.[74][75] Photodynamic Therapy has been shown to improve survival and quality of life [76]

Prognosis

Surgical resection offers the only potential chance of cure in cholangiocarcinoma. For non-resectable cases, the 5-year survival rate is 0% where the disease is inoperable because distal lymph nodes show metastases,[77] and less than 5% in general.[78] Overall median duration of survival is less than 6 months[79] in inoperable, untreated, otherwise healthy patients with tumors involving the liver by way of the intrahepatic bile ducts and hepatic portal vein.

For surgical cases, the odds of cure vary depending on the tumor location and whether the tumor can be completely, or only partially, removed. Distal cholangiocarcinomas (those arising from the common bile duct) are generally treated surgically with a Whipple procedure; long-term survival rates range from 15%–25%, although one series reported a five-year survival of 54% for patients with no involvement of the lymph nodes.[80] Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (those arising from the bile ducts within the liver) are usually treated with partial hepatectomy. Various series have reported survival estimates after surgery ranging from 22%–66%; the outcome may depend on involvement of lymph nodes and completeness of the surgery.[81] Perihilar cholangiocarcinomas (those occurring near where the bile ducts exit the liver) are least likely to be operable. When surgery is possible, they are generally treated with an aggressive approach often including removal of the gallbladder and potentially part of the liver. In patients with operable perihilar tumors, reported 5-year survival rates range from 20%–50%.[82]

The prognosis may be worse for patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis who develop cholangiocarcinoma, likely because the cancer is not detected until it is advanced.[12][83] Some evidence suggests that outcomes may be improving with more aggressive surgical approaches and adjuvant therapy.[84]

Epidemiology

Cholangiocarcinoma is an adenocarcinoma of the biliary tract,[85] along with pancreatic cancer (which occurs about 20 times more frequently),[86] gall bladder cancer (which occurs twice as often), and cancer of the ampulla of Vater. Treatments and clinical trials for pancreatic cancer, being far more prevalent, are often taken as a starting point for managing cholangiocarcinoma, even though the biologies are different enough that chemotherapies can put pancreatic cancer into permanent remission whereas there are no reports in the literature of long-term survival due to chemotherapy or radiation applied to an inoperable cholangiocarcinoma case.

| Country | IC (men/women) | EC (men/women) |

|---|---|---|

| U.S.A. | 0.60 / 0.43 | 0.70 / 0.87 |

| Japan | 0.23 / 0.10 | 5.87 / 5.20 |

| Australia | 0.70 / 0.53 | 0.90 / 1.23 |

| England/Wales | 0.83 / 0.63 | 0.43 / 0.60 |

| Scotland | 1.17 / 1.00 | 0.60 / 0.73 |

| France | 0.27 / 0.20 | 1.20 / 1.37 |

| Italy | 0.13 / 0.13 | 2.10 / 2.60 |

Cholangiocarcinoma is a relatively rare form of cancer; each year, approximately 2,000 to 3,000 new cases are diagnosed in the United States, translating into an annual incidence of 1–2 cases per 100,000 people.[1] Autopsy series have reported a prevalence of 0.01% to 0.46%.[88][89] There is a higher prevalence of cholangiocarcinoma in Asia, which has been attributed to endemic chronic parasitic infestation. The incidence of cholangiocarcinoma increases with age, and the disease is slightly more common in men than in women (possibly due to the higher rate of primary sclerosing cholangitis, a major risk factor, in men).[38] The prevalence of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis may be as high as 30%, based on autopsy studies.[12]

Multiple studies have documented a steady increase in the incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma over the past several decades; increases have been seen in North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia.[90] The reasons for the increasing occurrence of cholangiocarcinoma are unclear; improved diagnostic methods may be partially responsible, but the prevalence of potential risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma, such as HIV infection, has also been increasing during this time frame.[19]

Notable Victims

Ray Manzarek, keyboard player of The Doors, died from bile duct cancer.

Jeffrey Lynn Millar, American cartoonist

Walter Payton, running back, Chicago Bears

Peter Wintonick, Documentary Filmmaker

Notes

- ^ a b Landis S, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo P (1998). "Cancer statistics, 1998". CA Cancer J Clin. 48 (1): 6–29. doi:10.3322/canjclin.48.1.6. PMID 9449931.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Patel T (2002). "Worldwide trends in mortality from biliary tract malignancies". BMC Cancer. 2: 10. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-2-10. PMC 113759. PMID 11991810.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Zervos E, Osborne D, Goldin S, Villadolid D, Thometz D, Durkin A, Carey L, Rosemurgy A (2005). "Stage does not predict survival after resection of hilar cholangiocarcinomas promoting an aggressive operative approach". Am J Surg. 190 (5): 810–5. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.07.025. PMID 16226963.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Mark Feldman, Lawrence S. Friedman, Lawrence J. Brandt, ed. (July 21, 2006). Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease (8th ed.). Saunders. pp. 1493–6. ISBN 978-1-4160-0245-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Tsao J, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Hayakawa N, Kondo S, Nagino M, Miyachi M, Kanai M, Uesaka K, Oda K, Rossi R, Braasch J, Dugan J (2000). "Management of Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: Comparison of an American and a Japanese Experience". Ann Surg. 232 (2): 166–74. doi:10.1097/00000658-200008000-00003. PMC 1421125. PMID 10903592.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rajagopalan V, Daines W, Grossbard M, Kozuch P (2004). "Gallbladder and biliary tract carcinoma: A comprehensive update, Part 1". Oncology (Williston Park). 18 (7): 889–96. PMID 15255172.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nagorney D, Donohue J, Farnell M, Schleck C, Ilstrup D (1993). "Outcomes after curative resections of cholangiocarcinoma". Arch Surg. 128 (8): 871–7, discussion 877–9. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420200045008. PMID 8393652.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bile duct cancer: cause and treatment

- ^ a b Nakeeb A, Pitt H, Sohn T, Coleman J, Abrams R, Piantadosi S, Hruban R, Lillemoe K, Yeo C, Cameron J (1996). "Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors". Ann Surg. 224 (4): 463–73, discussion 473–5. doi:10.1097/00000658-199610000-00005. PMC 1235406. PMID 8857851.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chapman R (1999). "Risk factors for biliary tract carcinogenesis". Ann Oncol. 10 (Suppl 4): 308–11. doi:10.1023/A:1008313809752. PMID 10436847.

- ^ Epidemiologic studies which have addressed the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in people with primary sclerosing cholangitis include the following:

- Bergquist A, Ekbom A, Olsson R, Kornfeldt D, Lööf L, Danielsson A, Hultcrantz R, Lindgren S, Prytz H, Sandberg-Gertzén H, Almer S, Granath F, Broomé U (2002). "Hepatic and extrahepatic malignancies in primary sclerosing cholangitis". J Hepatol. 36 (3): 321–7. doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(01)00288-4. PMID 11867174.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bergquist A, Glaumann H, Persson B, Broomé U (1998). "Risk factors and clinical presentation of hepatobiliary carcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a case-control study". Hepatology. 27 (2): 311–6. doi:10.1002/hep.510270201. PMID 9462625.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Burak K, Angulo P, Pasha T, Egan K, Petz J, Lindor K (2004). "Incidence and risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis". Am J Gastroenterol. 99 (3): 523–6. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04067.x. PMID 15056096.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Bergquist A, Ekbom A, Olsson R, Kornfeldt D, Lööf L, Danielsson A, Hultcrantz R, Lindgren S, Prytz H, Sandberg-Gertzén H, Almer S, Granath F, Broomé U (2002). "Hepatic and extrahepatic malignancies in primary sclerosing cholangitis". J Hepatol. 36 (3): 321–7. doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(01)00288-4. PMID 11867174.

- ^ a b c Rosen C, Nagorney D, Wiesner R, Coffey R, LaRusso N (1991). "Cholangiocarcinoma complicating primary sclerosing cholangitis". Ann Surg. 213 (1): 21–5. doi:10.1097/00000658-199101000-00004. PMC 1358305. PMID 1845927.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Watanapa P (1996). "Cholangiocarcinoma in patients with opisthorchiasis". Br J Surg. 83 (8): 1062–64. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800830809. PMID 8869303.

- ^ Watanapa P, Watanapa W (2002). "Liver fluke-associated cholangiocarcinoma". Br J Surg. 89 (8): 962–70. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02143.x. PMID 12153620.

- ^ Shin H, Lee C, Park H, Seol S, Chung J, Choi H, Ahn Y, Shigemastu T (1996). "Hepatitis B and C virus, Clonorchis sinensis for the risk of liver cancer: a case-control study in Pusan, Korea". Int J Epidemiol. 25 (5): 933–40. doi:10.1093/ije/25.5.933. PMID 8921477.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kobayashi M, Ikeda K, Saitoh S, Suzuki F, Tsubota A, Suzuki Y, Arase Y, Murashima N, Chayama K, Kumada H (2000). "Incidence of primary cholangiocellular carcinoma of the liver in Japanese patients with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis". Cancer. 88 (11): 2471–7. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(20000601)88:11<2471::AID-CNCR7>3.0.CO;2-T. PMID 10861422.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yamamoto S, Kubo S, Hai S, Uenishi T, Yamamoto T, Shuto T, Takemura S, Tanaka H, Yamazaki O, Hirohashi K, Tanaka T (2004). "Hepatitis C virus infection as a likely etiology of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma". Cancer Sci. 95 (7): 592–5. doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb02492.x. PMID 15245596.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lu H, Ye M, Thung S, Dash S, Gerber M (2000). "Detection of hepatitis C virus RNA sequences in cholangiocarcinomas in Chinese and American patients". Chin Med J (Engl). 113 (12): 1138–41. PMID 11776153.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Shaib Y, El-Serag H, Davila J, Morgan R, McGlynn K (2005). "Risk factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a case-control study". Gastroenterology. 128 (3): 620–6. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.048. PMID 15765398.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sorensen H, Friis S, Olsen J, Thulstrup A, Mellemkjaer L, Linet M, Trichopoulos D, Vilstrup H, Olsen J (1998). "Risk of liver and other types of cancer in patients with cirrhosis: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark". Hepatology. 28 (4): 921–5. doi:10.1002/hep.510280404. PMID 9755226.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lipsett P, Pitt H, Colombani P, Boitnott J, Cameron J (1994). "Choledochal cyst disease. A changing pattern of presentation". Ann Surg. 220 (5): 644–52. doi:10.1097/00000658-199411000-00007. PMC 1234452. PMID 7979612.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dayton M, Longmire W, Tompkins R (1983). "Caroli's Disease: a premalignant condition?". Am J Surg. 145 (1): 41–8. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(83)90164-2. PMID 6295196.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mecklin J, Järvinen H, Virolainen M (1992). "The association between cholangiocarcinoma and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma". Cancer. 69 (5): 1112–4. doi:10.1002/cncr.2820690508. PMID 1310886.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lee S, Kim M, Lee S, Jang S, Song M, Kim K, Kim H, Seo D, Song D, Yu E, Lee S, Min Y (2004). "Clinicopathologic review of 58 patients with biliary papillomatosis". Cancer. 100 (4): 783–93. doi:10.1002/cncr.20031. PMID 14770435.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lee C, Wu C, Chen G (2002). "What is the impact of coexistence of hepatolithiasis on cholangiocarcinoma?". J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 17 (9): 1015–20. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02779.x. PMID 12167124.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Su C, Shyr Y, Lui W, P'Eng F (1997). "Hepatolithiasis associated with cholangiocarcinoma". Br J Surg. 84 (7): 969–73. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800840717. PMID 9240138.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Donato F, Gelatti U, Tagger A, Favret M, Ribero M, Callea F, Martelli C, Savio A, Trevisi P, Nardi G (2001). "Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and hepatitis C and B virus infection, alcohol intake, and hepatolithiasis: a case-control study in Italy". Cancer Causes Control. 12 (10): 959–64. doi:10.1023/A:1013747228572. PMID 11808716.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sahani D, Prasad S, Tannabe K, Hahn P, Mueller P, Saini S (2003). "Thorotrast-induced cholangiocarcinoma: case report". Abdom Imaging. 28 (1): 72–4. doi:10.1007/s00261-001-0148-y. PMID 12483389.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zhu A, Lauwers G, Tanabe K (2004). "Cholangiocarcinoma in association with Thorotrast exposure". J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 11 (6): 430–3. doi:10.1007/s00534-004-0924-5. PMID 15619021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Klatskin G (1965). "Adenocarcinoma Of The Hepatic Duct At Its Bifurcation Within The Porta Hepatis. An Unusual Tumor With Distinctive Clinical And Pathological Features". Am J Med. 38 (2): 241–56. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(65)90178-6. PMID 14256720.

- ^ Roskams T (2006). "Liver stem cells and their implication in hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma". Oncogene. 25 (27): 3818–22. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209558. PMID 16799623.

- ^ Liu C, Wang J, Ou Q (2004). "Possible stem cell origin of human cholangiocarcinoma". World J Gastroenterol. 10 (22): 3374–6. PMID 15484322.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sell S, Dunsford H (1989). "Evidence for the stem cell origin of hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma". Am J Pathol. 134 (6): 1347–63. PMC 1879951. PMID 2474256.

- ^ a b Sirica A (2005). "Cholangiocarcinoma: molecular targeting strategies for chemoprevention and therapy". Hepatology. 41 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1002/hep.20537. PMID 15690474.

- ^ Holzinger F, Z'graggen K, Büchler M (1999). "Mechanisms of biliary carcinogenesis: a pathogenetic multi-stage cascade towards cholangiocarcinoma". Ann Oncol. 10 (Suppl 4): 122–6. doi:10.1023/A:1008321710719. PMID 10436802.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gores G (2003). "Cholangiocarcinoma: current concepts and insights". Hepatology. 37 (5): 961–9. doi:10.1053/jhep.2003.50200. PMID 12717374.

- ^ de Groen P, Gores G, LaRusso N, Gunderson L, Nagorney D (1999). "Biliary tract cancers". N Engl J Med. 341 (18): 1368–78. doi:10.1056/NEJM199910283411807. PMID 10536130.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Henson D, Albores-Saavedra J, Corle D (1992). "Carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile ducts. Histologic types, stage of disease, grade, and survival rates". Cancer. 70 (6): 1498–501. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19920915)70:6<1498::AID-CNCR2820700609>3.0.CO;2-C. PMID 1516001.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Studies of the performance of serum markers for cholangiocarcinoma (such as carcinoembryonic antigen and CA19-9) in patients with and without primary sclerosing cholangitis include the following:

- Nehls O, Gregor M, Klump B (2004). "Serum and bile markers for cholangiocarcinoma". Semin Liver Dis. 24 (2): 139–54. doi:10.1055/s-2004-828891. PMID 15192787.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Siqueira E, Schoen R, Silverman W, Martin J, Rabinovitz M, Weissfeld J, Abu-Elmaagd K, Madariaga J, Slivka A, Martini J (2002). "Detecting cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis". Gastrointest Endosc. 56 (1): 40–7. doi:10.1067/mge.2002.125105. PMID 12085033.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Levy C, Lymp J, Angulo P, Gores G, Larusso N, Lindor K (2005). "The value of serum CA 19-9 in predicting cholangiocarcinomas in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis". Dig Dis Sci. 50 (9): 1734–40. doi:10.1007/s10620-005-2927-8. PMID 16133981.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Patel A, Harnois D, Klee G, LaRusso N, Gores G (2000). "The utility of CA 19-9 in the diagnoses of cholangiocarcinoma in patients without primary sclerosing cholangitis". Am J Gastroenterol. 95 (1): 204–7. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01685.x. PMID 10638584.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Nehls O, Gregor M, Klump B (2004). "Serum and bile markers for cholangiocarcinoma". Semin Liver Dis. 24 (2): 139–54. doi:10.1055/s-2004-828891. PMID 15192787.

- ^ Saini S (1997). "Imaging of the hepatobiliary tract". N Engl J Med. 336 (26): 1889–94. doi:10.1056/NEJM199706263362607. PMID 9197218.

- ^ Sharma M, Ahuja V (1999). "Aetiological spectrum of obstructive jaundice and diagnostic ability of ultrasonography: a clinician's perspective". Trop Gastroenterol. 20 (4): 167–9. PMID 10769604.

- ^ Bloom C, Langer B, Wilson S (1999). "Role of US in the detection, characterization, and staging of cholangiocarcinoma". Radiographics. 19 (5): 1199–218. PMID 10489176.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Valls C, Gumà A, Puig I, Sanchez A, Andía E, Serrano T, Figueras J (2000). "Intrahepatic peripheral cholangiocarcinoma: CT evaluation". Abdom Imaging. 25 (5): 490–6. doi:10.1007/s002610000079. PMID 10931983.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tillich M, Mischinger H, Preisegger K, Rabl H, Szolar D (1998). "Multiphasic helical CT in diagnosis and staging of hilar cholangiocarcinoma". AJR Am J Roentgenol. 171 (3): 651–8. doi:10.2214/ajr.171.3.9725291. PMID 9725291.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zhang Y, Uchida M, Abe T, Nishimura H, Hayabuchi N, Nakashima Y (1999). "Intrahepatic peripheral cholangiocarcinoma: comparison of dynamic CT and dynamic MRI". J Comput Assist Tomogr. 23 (5): 670–7. doi:10.1097/00004728-199909000-00004. PMID 10524843.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sugiyama M, Hagi H, Atomi Y, Saito M (1997). "Diagnosis of portal venous invasion by pancreatobiliary carcinoma: value of endoscopic ultrasonography". Abdom Imaging. 22 (4): 434–8. doi:10.1007/s002619900227. PMID 9157867.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schwartz L, Coakley F, Sun Y, Blumgart L, Fong Y, Panicek D (1998). "Neoplastic pancreaticobiliary duct obstruction: evaluation with breath-hold MR cholangiopancreatography". AJR Am J Roentgenol. 170 (6): 1491–5. doi:10.2214/ajr.170.6.9609160. PMID 9609160.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zidi S, Prat F, Le Guen O, Rondeau Y, Pelletier G (2000). "Performance characteristics of magnetic resonance cholangiography in the staging of malignant hilar strictures". Gut. 46 (1): 103–6. doi:10.1136/gut.46.1.103. PMC 1727781. PMID 10601064.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lee M, Park K, Shin Y, Yoon H, Sung K, Kim M, Lee S, Kang E (2003). "Preoperative evaluation of hilar cholangiocarcinoma with contrast-enhanced three-dimensional fast imaging with steady-state precession magnetic resonance angiography: comparison with intraarterial digital subtraction angiography". World J Surg. 27 (3): 278–83. doi:10.1007/s00268-002-6701-1. PMID 12607051.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yeh T, Jan Y, Tseng J, Chiu C, Chen T, Hwang T, Chen M (2000). "Malignant perihilar biliary obstruction: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographic findings". Am J Gastroenterol. 95 (2): 432–40. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01763.x. PMID 10685746.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Freeman M, Sielaff T (2003). "A modern approach to malignant hilar biliary obstruction". Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 3 (4): 187–201. PMID 14668691.

- ^ Szklaruk J, Tamm E, Charnsangavej C (2002). "Preoperative imaging of biliary tract cancers". Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 11 (4): 865–76. doi:10.1016/S1055-3207(02)00032-7. PMID 12607576.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Weber S, DeMatteo R, Fong Y, Blumgart L, Jarnagin W (2002). "Staging Laparoscopy in Patients With Extrahepatic Biliary Carcinoma: Analysis of 100 Patients". Ann Surg. 235 (3): 392–9. doi:10.1097/00000658-200203000-00011. PMC 1422445. PMID 11882761.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Callery M, Strasberg S, Doherty G, Soper N, Norton J (1997). "Staging laparoscopy with laparoscopic ultrasonography: optimizing resectability in hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancy". J Am Coll Surg. 185 (1): 33–9. PMID 9208958.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Länger F, von Wasielewski R, Kreipe HH (2006). "[The importance of immunohistochemistry for the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinomas]". Pathologe (in German). 27 (4): 244–50. doi:10.1007/s00292-006-0836-z. PMID 16758167.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Darwin PE, Kennedy A. Cholangiocarcinoma at eMedicine

- ^ Su C, Tsay S, Wu C, Shyr Y, King K, Lee C, Lui W, Liu T, P'eng F (1996). "Factors influencing postoperative morbidity, mortality, and survival after resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma". Ann Surg. 223 (4): 384–94. doi:10.1097/00000658-199604000-00007. PMC 1235134. PMID 8633917.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ C. B. Rosen, J. K. Heimbach, and G. J. Gores. "Surgery for cholangiocarcinoma: the role of liver transplantation". The Official Journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Heimbach JK, Gores GJ, Haddock MG; et al. (2006). "Predictors of disease recurrence following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and liver transplantation for unresectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma". Transplantation. 82 (12): 1703–7. doi:10.1097/01.tp.0000253551.43583.d1. PMID 17198263.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Todoroki T, Ohara K, Kawamoto T, Koike N, Yoshida S, Kashiwagi H, Otsuka M, Fukao K (2000). "Benefits of adjuvant radiotherapy after radical resection of locally advanced main hepatic duct carcinoma". Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 46 (3): 581–7. doi:10.1016/S0360-3016(99)00472-1. PMID 10701737.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Alden M, Mohiuddin M (1994). "The impact of radiation dose in combined external beam and intraluminal Ir-192 brachytherapy for bile duct cancer". Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 28 (4): 945–51. doi:10.1016/0360-3016(94)90115-5. PMID 8138448.

- ^ González González D, Gouma D, Rauws E, van Gulik T, Bosma A, Koedooder C (1999). "Role of radiotherapy, in particular intraluminal brachytherapy, in the treatment of proximal bile duct carcinoma". Ann Oncol. 10 (Suppl 4): 215–20. doi:10.1023/A:1008339709327. PMID 10436826.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pitt H, Nakeeb A, Abrams R, Coleman J, Piantadosi S, Yeo C, Lillemore K, Cameron J (1995). "Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Postoperative radiotherapy does not improve survival". Ann Surg. 221 (6): 788–97, discussion 797–8. doi:10.1097/00000658-199506000-00017. PMC 1234714. PMID 7794082.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Takada T, Amano H, Yasuda H, Nimura Y, Matsushiro T, Kato H, Nagakawa T, Nakayama T (2002). "Is postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy useful for gallbladder carcinoma? A phase III multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial in patients with resected pancreaticobiliary carcinoma". Cancer. 95 (8): 1685–95. doi:10.1002/cncr.10831. PMID 12365016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Template:PDFlink. Accessed March 13, 2007.

- ^ Vauthey J, Blumgart L (1994). "Recent advances in the management of cholangiocarcinomas". Semin. Liver Dis. 14 (2): 109–14. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1007302. PMID 8047893.

- ^ Glimelius B, Hoffman K, Sjödén P, Jacobsson G, Sellström H, Enander L, Linné T, Svensson C (1996). "Chemotherapy improves survival and quality of life in advanced pancreatic and biliary cancer". Ann Oncol. 7 (6): 593–600. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a010676. PMID 8879373.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Choi C, Choi I, Seo J, Kim B, Kim J, Kim C, Um S, Kim J, Kim Y (2000). "Effects of 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin in the treatment of pancreatic-biliary tract adenocarcinomas". Am J Clin Oncol. 23 (4): 425–8. doi:10.1097/00000421-200008000-00023. PMID 10955877.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Park J, Oh S, Kim S, Kwon H, Kim J, Jin-Kim H, Kim Y (2005). "Single-agent gemcitabine in the treatment of advanced biliary tract cancers: a phase II study". Jpn J Clin Oncol. 35 (2): 68–73. doi:10.1093/jjco/hyi021. PMID 15709089.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Giuliani F, Gebbia V, Maiello E, Borsellino N, Bajardi E, Colucci G (2006). "Gemcitabine and cisplatin for inoperable and/or metastatic biliary tree carcinomas: a multicenter phase II study of the Gruppo Oncologico dell'Italia Meridionale (GOIM)". Ann Oncol. 17 (Suppl 7): vii73–7. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdl956. PMID 16760299.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bhargava P, Jani C, Savarese D, O'Donnell J, Stuart K, Rocha Lima C (2003). "Gemcitabine and irinotecan in locally advanced or metastatic biliary cancer: preliminary report". Oncology (Williston Park). 17 (9 Suppl 8): 23–6. PMID 14569844.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Knox J, Hedley D, Oza A, Feld R, Siu L, Chen E, Nematollahi M, Pond G, Zhang J, Moore M (2005). "Combining gemcitabine and capecitabine in patients with advanced biliary cancer: a phase II trial". J Clin Oncol. 23 (10): 2332–8. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.51.008. PMID 15800324.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Philip P, Mahoney M, Allmer C, Thomas J, Pitot H, Kim G, Donehower R, Fitch T, Picus J, Erlichman C (2006). "Phase II study of erlotinib in patients with advanced biliary cancer". J Clin Oncol. 24 (19): 3069–74. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3579. PMID 16809731.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ortner M, Caca K, Berr F, Liebetruth J, Mansmann U, Huster D, Voderholzer W, Schachschal G, Mössner J, Lochs H (2003). "Successful photodynamic therapy for nonresectable cholangiocarcinoma: a randomized prospective study". Gastroenterology. 125 (5): 1355–63. doi:10.1016/j.gastro.2003.07.015. PMID 14598251.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zoepf T, Jakobs R, Arnold J, Apel D, Riemann J (2005). "Palliation of nonresectable bile duct cancer: improved survival after photodynamic therapy". Am J Gastroenterol. 100 (11): 2426–30. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00318.x. PMID 16279895.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Talreja JP, Kahaleh M (2010). "Photodynamic therapy for cholangiocarcinoma". Gut Liver. 4 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1): S62–6. doi:10.5009/gnl.2010.4.S1.S62. PMC 2989550. PMID 21103297.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Yamamoto M, Takasaki K, Yoshikawa T (1999). "Lymph Node Metastasis in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma". Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology. 29 (3): 147–150. doi:10.1093/jjco/29.3.147. PMID 10225697.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Farley D, Weaver A, Nagorney D (1995). ""Natural history" of unresected cholangiocarcinoma: patient outcome after noncurative intervention". Mayo Clin Proc. 70 (5): 425–9. doi:10.4065/70.5.425. PMID 7537346.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Grove MK, Hermann RE, Vogt DP, Broughan TA (1991). "Role of radiation after operative palliation in cancer of the proximal bile ducts". Am J Surg. 161 (4): 454–458. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(91)91111-U. PMID 1709795.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Studies of surgical outcomes in distal cholangiocarcinoma include:

- Nakeeb A, Pitt H, Sohn T, Coleman J, Abrams R, Piantadosi S, Hruban R, Lillemoe K, Yeo C, Cameron J (1996). "Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors". Ann Surg. 224 (4): 463–73, discussion 473–5. doi:10.1097/00000658-199610000-00005. PMC 1235406. PMID 8857851.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Nagorney D, Donohue J, Farnell M, Schleck C, Ilstrup D (1993). "Outcomes after curative resections of cholangiocarcinoma". Arch Surg. 128 (8): 871–7, discussion 877–9. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420200045008. PMID 8393652.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jang J, Kim S, Park D, Ahn Y, Yoon Y, Choi M, Suh K, Lee K, Park Y (2005). "Actual Long-term Outcome of Extrahepatic Bile Duct Cancer After Surgical Resection". Ann Surg. 241 (1): 77–84. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000150166.94732.88. PMC 1356849. PMID 15621994.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bortolasi L, Burgart L, Tsiotos G, Luque-De León E, Sarr M (2000). "Adenocarcinoma of the distal bile duct. A clinicopathologic outcome analysis after curative resection". Dig Surg. 17 (1): 36–41. doi:10.1159/000018798. PMID 10720830.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fong Y, Blumgart L, Lin E, Fortner J, Brennan M (1996). "Outcome of treatment for distal bile duct cancer". Br J Surg. 83 (12): 1712–5. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800831217. PMID 9038548.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Nakeeb A, Pitt H, Sohn T, Coleman J, Abrams R, Piantadosi S, Hruban R, Lillemoe K, Yeo C, Cameron J (1996). "Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors". Ann Surg. 224 (4): 463–73, discussion 473–5. doi:10.1097/00000658-199610000-00005. PMC 1235406. PMID 8857851.

- ^ Studies of outcome in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma include:

- Nakeeb A, Pitt H, Sohn T, Coleman J, Abrams R, Piantadosi S, Hruban R, Lillemoe K, Yeo C, Cameron J (1996). "Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors". Ann Surg. 224 (4): 463–73, discussion 473–5. doi:10.1097/00000658-199610000-00005. PMC 1235406. PMID 8857851.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lieser M, Barry M, Rowland C, Ilstrup D, Nagorney D (1998). "Surgical management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a 31-year experience". J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 5 (1): 41–7. doi:10.1007/PL00009949. PMID 9683753.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Valverde A, Bonhomme N, Farges O, Sauvanet A, Flejou J, Belghiti J (1999). "Resection of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a Western experience". J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 6 (2): 122–7. doi:10.1007/s005340050094. PMID 10398898.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Nakagohri T, Asano T, Kinoshita H, Kenmochi T, Urashima T, Miura F, Ochiai T (2003). "Aggressive surgical resection for hilar-invasive and peripheral intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma". World J Surg. 27 (3): 289–93. doi:10.1007/s00268-002-6696-7. PMID 12607053.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Weber S, Jarnagin W, Klimstra D, DeMatteo R, Fong Y, Blumgart L (2001). "Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: resectability, recurrence pattern, and outcomes". J Am Coll Surg. 193 (4): 384–91. doi:10.1016/S1072-7515(01)01016-X. PMID 11584966.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Nakeeb A, Pitt H, Sohn T, Coleman J, Abrams R, Piantadosi S, Hruban R, Lillemoe K, Yeo C, Cameron J (1996). "Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors". Ann Surg. 224 (4): 463–73, discussion 473–5. doi:10.1097/00000658-199610000-00005. PMC 1235406. PMID 8857851.

- ^ Estimates of survival after surgery for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma include:

- Burke E, Jarnagin W, Hochwald S, Pisters P, Fong Y, Blumgart L (1998). "Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: patterns of spread, the importance of hepatic resection for curative operation, and a presurgical clinical staging system". Ann Surg. 228 (3): 385–94. doi:10.1097/00000658-199809000-00011. PMC 1191497. PMID 9742921.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tsao J, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Hayakawa N, Kondo S, Nagino M, Miyachi M, Kanai M, Uesaka K, Oda K, Rossi R, Braasch J, Dugan J (2000). "Management of Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: Comparison of an American and a Japanese Experience". Ann Surg. 232 (2): 166–74. doi:10.1097/00000658-200008000-00003. PMC 1421125. PMID 10903592.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Chamberlain R, Blumgart L (2000). "Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a review and commentary". Ann Surg Oncol. 7 (1): 55–66. doi:10.1007/s10434-000-0055-4. PMID 10674450.

- Washburn W, Lewis W, Jenkins R (1995). "Aggressive surgical resection for cholangiocarcinoma". Arch Surg. 130 (3): 270–6. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430030040006. PMID 7534059.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Nagino M, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Kanai M, Uesaka K, Hayakawa N, Yamamoto H, Kondo S, Nishio H (1998). "Segmental liver resections for hilar cholangiocarcinoma". Hepatogastroenterology. 45 (19): 7–13. PMID 9496478.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rea D, Munoz-Juarez M, Farnell M, Donohue J, Que F, Crownhart B, Larson D, Nagorney D (2004). "Major hepatic resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: analysis of 46 patients". Arch Surg. 139 (5): 514–23, discussion 523–5. doi:10.1001/archsurg.139.5.514. PMID 15136352.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Launois B, Reding R, Lebeau G, Buard J (2000). "Surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: French experience in a collective survey of 552 extrahepatic bile duct cancers". J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 7 (2): 128–34. doi:10.1007/s005340050166. PMID 10982604.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Burke E, Jarnagin W, Hochwald S, Pisters P, Fong Y, Blumgart L (1998). "Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: patterns of spread, the importance of hepatic resection for curative operation, and a presurgical clinical staging system". Ann Surg. 228 (3): 385–94. doi:10.1097/00000658-199809000-00011. PMC 1191497. PMID 9742921.

- ^ Kaya M, de Groen P, Angulo P, Nagorney D, Gunderson L, Gores G, Haddock M, Lindor K (2001). "Treatment of cholangiocarcinoma complicating primary sclerosing cholangitis: the Mayo Clinic experience". Am J Gastroenterol. 96 (4): 1164–9. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03696.x. PMID 11316165.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nakeeb A, Tran K, Black M, Erickson B, Ritch P, Quebbeman E, Wilson S, Demeure M, Rilling W, Dua K, Pitt H (2002). "Improved survival in resected biliary malignancies". Surgery. 132 (4): 555–63, discission 563–4. doi:10.1067/msy.2002.127555. PMID 12407338.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://training.seer.cancer.gov/ss_module13_biliary_tract/unit01_sec01_intro.html Introduction

- ^ http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2005/results_single/sect_01_table.01.pdf

- ^ Khan S, Taylor-Robinson S, Toledano M, Beck A, Elliott P, Thomas H (2002). "Changing international trends in mortality rates for liver, biliary and pancreatic tumours". J Hepatol. 37 (6): 806–13. doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00297-0. PMID 12445422.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vauthey J, Blumgart L (1994). "Recent advances in the management of cholangiocarcinomas". Semin Liver Dis. 14 (2): 109–14. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1007302. PMID 8047893.

- ^ Cancer Statistics Home Page — National Cancer Institute

- ^ Multiple independent studies have documented a steady increase in the worldwide incidence of cholangiocarcinoma. Some relevant journal articles include:

- Patel T (2002). "Worldwide trends in mortality from biliary tract malignancies". BMC Cancer. 2: 10. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-2-10. PMC 113759. PMID 11991810.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Patel T (2001). "Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States". Hepatology. 33 (6): 1353–7. doi:10.1053/jhep.2001.25087. PMID 11391522.

- Shaib Y, Davila J, McGlynn K, El-Serag H (2004). "Rising incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a true increase?". J Hepatol. 40 (3): 472–7. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2003.11.030. PMID 15123362.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - West J, Wood H, Logan R, Quinn M, Aithal G (2006). "Trends in the incidence of primary liver and biliary tract cancers in England and Wales 1971–2001". Br J Cancer. 94 (11): 1751–8. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603127. PMC 2361300. PMID 16736026.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Khan S, Taylor-Robinson S, Toledano M, Beck A, Elliott P, Thomas H (2002). "Changing international trends in mortality rates for liver, biliary and pancreatic tumours". J Hepatol. 37 (6): 806–13. doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00297-0. PMID 12445422.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Welzel T, McGlynn K, Hsing A, O'Brien T, Pfeiffer R (2006). "Impact of classification of hilar cholangiocarcinomas (Klatskin tumors) on the incidence of intra- and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States". J Natl Cancer Inst. 98 (12): 873–5. doi:10.1093/jnci/djj234. PMID 16788161.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Patel T (2002). "Worldwide trends in mortality from biliary tract malignancies". BMC Cancer. 2: 10. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-2-10. PMC 113759. PMID 11991810.

External links

- American Cancer Society Detailed Guide to Bile Duct Cancer.

- Patient information on extrahepatic bile duct tumors, from the National Cancer Institute.

- Cancer.Net: Bile Duct Cancer

- The Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation: a resource for patients, friends, caregivers and loved ones of those affected by bile duct cancer.

- The Alan Morement Memorial Fund, the UK's only charity dedicated to the disease

- Macmillan/Cancerbackup page on Cholangiocarcinoma

Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link FA