Christopher Columbus: Difference between revisions

Marine 69-71 (talk | contribs) m Correcting, Columbus did not "discover" the New World because when he arrived there were already people living there |

Jrtayloriv (talk | contribs) m linkify |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

<!--ACCORDING TO [[WP:Style]], places of b./d. must be listed in the text proper--> |

<!--ACCORDING TO [[WP:Style]], places of b./d. must be listed in the text proper--> |

||

'''Christopher Columbus''' (c. 1451 – 20 May 1506) was a [[navigator]], [[colonialist|colonizer]] and [[explorer]] whose voyages across the [[Atlantic Ocean]] led to general European awareness of the [[Americas|American continents]] in the [[Western Hemisphere]]. With his four voyages of exploration and several attempts at establishing a settlement on the island of [[Hispaniola]], all funded by [[Isabella I of Castile]], he initiated the process of [[Spanish colonization of the Americas|Spanish colonization]] which foreshadowed general [[European colonization of the Americas|European colonization]] of the "[[New World]]." |

'''Christopher Columbus''' (c. 1451 – 20 May 1506) was a [[navigator]], [[colonialist|colonizer]] and [[explorer]] whose voyages across the [[Atlantic Ocean]] led to general European awareness of the [[Americas|American continents]] in the [[Western Hemisphere]]. With his four voyages of exploration and several attempts at establishing a settlement on the island of [[Hispaniola]], all funded by [[Isabella I of Castile]], he initiated the process of [[Spanish colonization of the Americas|Spanish colonization]] which foreshadowed general [[European colonization of the Americas|European colonization]] of the "[[New World]]." |

||

Although not the first to reach the Americas from [[Europe]]—he was preceded by at least one other group, the [[Norsemen|Norse]], led by [[Leif Ericson]], who built a temporary settlement 500 years earlier at [[L'Anse aux Meadows]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pc.gc.ca/lhn-nhs/nl/meadows/index_e.asp |title=Parks Canada — L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site of Canada |publisher=Pc.gc.ca |date=2009-04-24 |accessdate=2009-07-29}}</ref>— Columbus initiated widespread contact between [[Demography of Europe|Europeans]] and [[Indigenous peoples of the Americas|indigenous Americans]]. |

|||

The term "[[pre-Columbian]]" is usually used to refer to the peoples and cultures of the Americas before the arrival of Columbus and his European successors. Columbus himself was responsible for the deaths of millions of Native Americans (estimates range between 1 and 3 million) in first 15 years of his colonization of the Caribbean<ref name="phus-zinn">{{cite book|last=Zinn|first=Howard|title=A People's History of the United States: 1492-Present|publisher=Harper Perennial|location=New York|date=2003|edition=Fifth Printing|pages=7|chapter=1|isbn=0060838655|language=English}}</ref><ref name="iau-churchill">{{cite book|last=Churchill|first=Ward|title=Indians Are Us?: Culture and Genocide in Native North America|publisher=Common Courage Press|date=December 1993|url=http://www.mit.edu/~thistle/v9/9.11/1columbus.html|accessdate=10-12-2009|language=English}}</ref>, including entire peoples' such as the [[Taino]]<ref name="taino-rouse">{{cite book|last=Rouse|first=Irving|title=The Tainos: Rise and Decline of the People Who Greeted Columbus (Paperback)|publisher=Yale University Press|date=July 28, 1993|isbn=0300056966|language=English}}</ref> and the [[Arawak]]<ref name="zinn-ph-arawak">{{cite book|last=Zinn|first=Howard|title=A People's History of the United States: 1492-Present|publisher=Harper Perennial|date=2003|edition=Fifth Printing|pages=5|chapter=1|isbn=0060838655|language=English}}</ref>, and was the founder of the practice of slavery in the Americas.<ref name="ph-zinn-slavery">{{cite book|last=Zinn|first=Howard|title=A People's History of the United States: 1492-Present|publisher=Harper Perennial|location=New York|date=2003|edition=Fifth Printing|pages=4|chapter=1|language=English}}</ref> |

|||

Academic consensus is that Columbus was born in [[Republic of Genoa|Genoa]], though there are [[Origin theories of Christopher Columbus|other theories]]. The name ''Christopher Columbus'' is the Anglicisation of the [[Latin]] ''Christophorus Columbus''. The original name in 15<sup>th</sup> century [[Ligurian language (Romance)|Genoese language]] was ''Christoffa''<ref>Rime diverse, Pavia, 1595, p.117</ref> ''Corombo''<ref>Ra Gerusalemme deliverâ, Genoa, 1755, XV-32</ref> ({{pron|kriˈʃtɔffa kuˈɹuŋbu}}) The name is rendered in modern Italian as ''Cristoforo Colombo'', in [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]] as ''Cristóvão Colombo'' (formerly ''Christovam Colom'') and in [[Spanish language|Spanish ]] as ''Cristóbal Colón''. |

Academic consensus is that Columbus was born in [[Republic of Genoa|Genoa]], though there are [[Origin theories of Christopher Columbus|other theories]]. The name ''Christopher Columbus'' is the Anglicisation of the [[Latin]] ''Christophorus Columbus''. The original name in 15<sup>th</sup> century [[Ligurian language (Romance)|Genoese language]] was ''Christoffa''<ref>Rime diverse, Pavia, 1595, p.117</ref> ''Corombo''<ref>Ra Gerusalemme deliverâ, Genoa, 1755, XV-32</ref> ({{pron|kriˈʃtɔffa kuˈɹuŋbu}}) The name is rendered in modern Italian as ''Cristoforo Colombo'', in [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]] as ''Cristóvão Colombo'' (formerly ''Christovam Colom'') and in [[Spanish language|Spanish ]] as ''Cristóbal Colón''. |

||

Revision as of 08:21, 12 October 2009

Christopher Columbus | |

|---|---|

Posthumous portrait of Christopher Columbus by Ridolfo Ghirlandaio. There are no known authentic portraits of Columbus. | |

| Born | c.1451 Genoa, Liguria |

| Died | 20 May 1506 Valladolid, Castile |

| Nationality | Genoese |

| Other names | Genoese: Christoffa Corombo Spanish: Cristóbal Colón Portuguese: Christovam Colom Latin: Christophorus Columbus |

| Occupations | Maritime explorer for the Crown of Castile |

| Title | Admiral of the Ocean Sea; Viceroy and Governor of the Indies |

| Spouse | Filipa Moniz (c. 1476-1485) |

| Children | Diego Fernando |

| Relatives | Giovanni Pellegrino, Giacomo and Bartolomeo Columbus (brothers) |

| Signature | |

| |

Christopher Columbus (c. 1451 – 20 May 1506) was a navigator, colonizer and explorer whose voyages across the Atlantic Ocean led to general European awareness of the American continents in the Western Hemisphere. With his four voyages of exploration and several attempts at establishing a settlement on the island of Hispaniola, all funded by Isabella I of Castile, he initiated the process of Spanish colonization which foreshadowed general European colonization of the "New World."

Although not the first to reach the Americas from Europe—he was preceded by at least one other group, the Norse, led by Leif Ericson, who built a temporary settlement 500 years earlier at L'Anse aux Meadows[1]— Columbus initiated widespread contact between Europeans and indigenous Americans.

The term "pre-Columbian" is usually used to refer to the peoples and cultures of the Americas before the arrival of Columbus and his European successors. Columbus himself was responsible for the deaths of millions of Native Americans (estimates range between 1 and 3 million) in first 15 years of his colonization of the Caribbean[2][3], including entire peoples' such as the Taino[4] and the Arawak[5], and was the founder of the practice of slavery in the Americas.[6]

Academic consensus is that Columbus was born in Genoa, though there are other theories. The name Christopher Columbus is the Anglicisation of the Latin Christophorus Columbus. The original name in 15th century Genoese language was Christoffa[7] Corombo[8] ([pronunciation?]) The name is rendered in modern Italian as Cristoforo Colombo, in Portuguese as Cristóvão Colombo (formerly Christovam Colom) and in Spanish as Cristóbal Colón.

Columbus's initial 1492 voyage came at a critical time of growing national imperialism and economic competition between developing nation states seeking wealth from the establishment of trade routes and colonies. In this sociopolitical climate, Columbus's far-fetched scheme won the attention of Isabella I of Castile. Severely underestimating the circumference of the Earth, he estimated that a westward route from Iberia to the Indies would be shorter and more direct than the overland trade route through Arabia. If true, this would allow Spain entry into the lucrative spice trade—heretofore commanded by the Arabs and Italians. Following his plotted course, he instead landed within the Bahamas Archipelago at a locale he named San Salvador. Mistaking the North-American island for the East-Asian mainland, he referred to its inhabitants as "Indios".

The anniversary of Columbus's 1492 landing in the Americas is observed as Columbus Day on October 12 in Spain and throughout the Americas, except that in the United States it is observed on the second Monday in October.

Early life

It is generally, although not universally, agreed that Christopher Columbus was born between 25 August and 31 October 1451 in Genoa, part of modern Italy.[9] His father was Domenico Colombo, a middle-class wool weaver, who later also had a cheese stand where Christopher was a helper, working both in Genoa and Savona. His mother was Susanna Fontanarossa. Bartolomeo, Giovanni Pellegrino and Giacomo were his brothers. Bartolomeo worked in a cartography workshop in Lisbon for at least part of his adulthood.[10]

Columbus never wrote any works in his native language, but it can be assumed this was the Genoese variety of Ligurian. In one of his writings, Columbus claims to have gone to the sea at the age of 10. In 1470 the Columbus family moved to Savona, where Domenico took over a tavern. In the same year, Columbus was on a Genoese ship hired in the service of René I of Anjou to support his attempt to conquer the Kingdom of Naples.

In 1473 Columbus began his apprenticeship as business agent for the important Centurione, Di Negro and Spinola families of Genoa. Later he allegedly made a trip to Chios, a Genoese colony in the Aegean Sea. In May 1476, he took part in an armed convoy sent by Genoa to carry a valuable cargo to northern Europe. He docked in Bristol, Galway, in Ireland and was possibly in Iceland in 1477. In 1479 Columbus reached his brother Bartolomeo in Lisbon, keeping on trading for the Centurione family. He married Filipa Moniz Perestrello, daughter of the Porto Santo governor, the Portuguese nobleman of Genoese origin Bartolomeu Perestrello. In 1479 or 1480, his son Diego was born. Some records report that Felipa died in 1485. It is also speculated that Columbus may have simply left his first wife. In either case Columbus found a mistress in Spain in 1487, a 20-year-old orphan named Beatriz Enriquez de Arana.[11]

Voyages

Europe had long enjoyed a safe land passage to China and India— sources of valued goods such as silk, spices, and opiates— under the hegemony of the Mongol Empire (the Pax Mongolica, or Mongol peace). With the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, the land route to Asia became more difficult. In response to this the Columbus brothers had, by the 1480s, developed a plan to travel to the Indies, then construed roughly as all of south and east Asia, by sailing directly west across the "Ocean Sea," i.e., the Atlantic.

Washington Irving's 1828 biography of Columbus popularized the idea that Columbus had difficulty obtaining support for his plan because Europeans thought the Earth was flat.[13] In fact, the primitive maritime navigation of the time relied on the stars and the curvature of the spherical Earth. The knowledge that the Earth was spherical was widespread, and the means of calculating its diameter using an astrolabe was known to both scholars and navigators.[14] A spherical Earth had been the general opinion of Ancient Greek science, and this view continued through the Middle Ages (for example, Bede mentions it in The Reckoning of Time). In fact Eratosthenes had measured the diameter of the Earth with good precision in the second century BC.[15] Where Columbus did differ from the generally accepted view of his time is his (incorrect) arguments that assumed a significantly smaller diameter for the Earth, claiming that Asia could be easily reached by sailing west across the Atlantic. Most scholars accepted Ptolemy's correct assessment that the terrestrial landmass (for Europeans of the time, comprising Eurasia and Africa) occupied 180 degrees of the terrestrial sphere, and dismissed Columbus's claim that the Earth was much smaller, and that Asia was only a few thousand nautical miles to the west of Europe. Columbus's error was put down to his lack of experience in navigation at sea.[16]

Columbus believed the (incorrect) calculations of Marinus of Tyre, putting the landmass at 225 degrees, leaving only 135 degrees of water. Moreover, Columbus believed that one degree represented a shorter distance on the Earth's surface than was actually the case. Finally, he read maps as if the distances were calculated in Italian miles (1,238 meters). Accepting the length of a degree to be 56⅔ miles, from the writings of Alfraganus, he therefore calculated the circumference of the Earth as 25,255 kilometers at most, and the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan as 3,000 Italian miles (3,700 km, or 2,300 statute miles). Columbus did not realize Alfraganus used the much longer Arabic mile (about 1,830 m).

The true circumference of the Earth is about 40,000 km (25,000 mi), a figure established by Eratosthenes in the second century BC,[15] and the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan 19,600 km (12,200 mi). No ship that was readily available in the 15th century could carry enough food and fresh water for such a journey. Most European sailors and navigators concluded, probably correctly, that sailors undertaking a westward voyage from Europe to Asia non-stop would die of thirst or starvation long before reaching their destination. Catholic Monarchs, however, having completed an expensive war in the Iberian Peninsula, were desperate for a competitive edge over other European countries in trade with the East Indies. Columbus promised such an advantage.

While Columbus's calculations underestimated the circumference of the Earth and the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan by the standards of his peers as well as in fact, Europeans generally assumed that the aquatic expanse between Europe and Asia was uninterrupted.[citation needed]

There was a further element of key importance in the plans of Columbus, a closely held fact discovered, or otherwise learned, by Columbus: the trade winds. A brisk wind from the east, commonly called an "easterly", propelled Santa María, La Niña, and La Pinta for five weeks from the Canaries. To return to Spain eastward against this prevailing wind would have required several months of an arduous sailing technique, called beating, during which food and drinkable water would have been utterly exhausted. Columbus returned home by following prevailing winds northeastward from the southern zone of the North Atlantic to the middle latitudes of the North Atlantic, where prevailing winds are eastward (westerly) to the coastlines of Western Europe, where the winds curve southward towards the Iberian Peninsula.[17] In fact, Columbus was wrong about degrees of longitude to be traversed and wrong about distance per degree, but he was right about a more vital fact: how to use the North Atlantic's great circular wind pattern, clockwise in direction, to get home.[18][19]

Funding campaign

In 1485, Columbus presented his plans to John II, King of Portugal. He proposed the king equip three sturdy ships and grant Columbus one year's time to sail out into the Atlantic, search for a western route to the Orient, and return. Columbus also requested he be made "Great Admiral of the Ocean", appointed governor of any and all lands he discovered, and given one-tenth of all revenue from those lands. The king submitted the proposal to his experts, who rejected it. It was their considered opinion that Columbus's estimation of a travel distance of 2,400 miles (3,860 km) was, in fact, far too short.[16]

In 1488 Columbus appealed to the court of Portugal once again, and once again John invited him to an audience. It also proved unsuccessful, in part because not long afterwards Bartholomeu Dias returned to Portugal following a successful rounding of the southern tip of Africa. With an eastern sea route now under its control, Portugal was no longer interested in trailblazing a western route to Asia.

Columbus travelled from Portugal to both Genoa and Venice, but he received encouragement from neither. Previously he had his brother sound out Henry VII of England, to see if the English monarch might not be more amenable to Columbus's proposal. After much carefully considered hesitation Henry's invitation came, too late. Columbus had already committed himself to Spain.

He had sought an audience from the monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, who had united many kingdoms in the Iberian Peninsula by marrying, and were ruling together. On 1 May 1486, permission having been granted, Columbus presented his plans to Queen Isabella, who, in turn, referred it to a committee. After the passing of much time, these savants of Spain, like their counterparts in Portugal, reported back that Columbus had judged the distance to Asia much too short. They pronounced the idea impractical, and advised their Royal Highnesses to pass on the proposed venture.

However, to keep Columbus from taking his ideas elsewhere, and perhaps to keep their options open, the Catholic Monarchs gave him an annual allowance of 12,000 maravedis and in 1489 furnished him with a letter ordering all cities and towns under their domain to provide him food and lodging at no cost.[20]

After continually lobbying at the Spanish court and two years of negotiations, he finally had success in 1492. Ferdinand and Isabella had just conquered Granada, the last Muslim stronghold on the Iberian peninsula, and they received Columbus in Córdoba, in the Alcázar castle. Isabella turned Columbus down on the advice of her confessor, and he was leaving town by mule in despair, when Ferdinand intervened. Isabella then sent a royal guard to fetch him and Ferdinand later claimed credit for being "the principal cause why those islands were discovered".

About half of the financing was to come from private Italian investors, whom Columbus had already lined up. Financially broke after the Granada campaign, the monarchs left it to the royal treasurer to shift funds among various royal accounts on behalf of the enterprise. Columbus was to be made "Admiral of the Seas" and would receive a portion of all profits. The terms were unusually generous, but as his son later wrote, the monarchs did not really expect him to return.

According to the contract that Columbus made with King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, if Columbus discovered any new islands or mainland, he would receive many high rewards. In terms of power, he would be given the rank of Admiral of the Ocean Sea and appointed Viceroy and Governor of all the new lands. He had the right to nominate three persons, from whom the sovereigns would choose one, for any office in the new lands. He would be entitled to 10% of all the revenues from the new lands in perpetuity; this part was denied to him in the contract, although it was one of his demands. Additionally, he would also have the option of buying one-eighth interest in any commercial venture with the new lands and receive one-eighth of the profits.

Columbus was later arrested in 1500 and supplanted from these posts. After his death, Columbus's sons, Diego and Fernando, took legal action to enforce their father's contract. Many of the smears against Columbus were initiated by the Castilian crown during these lengthy court cases, known as the pleitos colombinos. The family had some success in their first litigation, as a judgment of 1511 confirmed Diego's position as Viceroy, but reduced his powers. Diego resumed litigation in 1512, which lasted until 1536, and further disputes continued until 1790.[21]

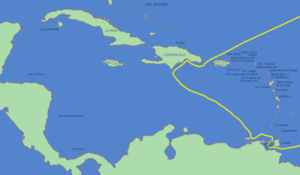

First voyage

|

|

|

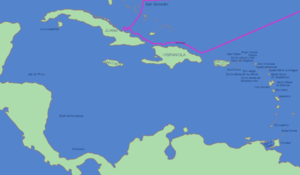

On the evening of 3 August 1492, Columbus departed from Palos de la Frontera with three ships; one larger carrack, Santa María, nicknamed Gallega (the Galician), and two smaller caravels, Pinta (the Painted) and Santa Clara, nicknamed Niña after her owner Juan Niño of Moguer.[22] They were property of Juan de la Cosa and the Pinzón brothers (Martín Alonso and Vicente Yáñez), but the monarchs forced the Palos inhabitants to contribute to the expedition. Columbus first sailed to the Canary Islands, which were owned by Castile, where he restocked the provisions and made repairs. On 6 September he departed San Sebastián de la Gomera for what turned out to be a five-week voyage across the ocean.

Land was sighted at 2 a.m. on 12 October 1492, by a sailor named Rodrigo de Triana (also known as Juan Rodríguez Bermejo) aboard Pinta.[23] Columbus called the island (in what is now The Bahamas) San Salvador; the natives called it Guanahani. Exactly which island in the Bahamas this corresponds to is an unresolved topic; prime candidates are Samana Cay, Plana Cays, or San Salvador Island (so named in 1925 in the belief that it was Columbus's San Salvador). The indigenous people he encountered, the Lucayan, Taíno or Arawak, were peaceful and friendly. From the 12 October 1492 entry in his journal he wrote of them, "Many of the men I have seen have scars on their bodies, and when I made signs to them to find out how this happened, they indicated that people from other nearby islands come to San Salvador to capture them; they defend themselves the best they can. I believe that people from the mainland come here to take them as slaves. They ought to make good and skilled servants, for they repeat very quickly whatever we say to them. I think they can very easily be made Christians, for they seem to have no religion. If it pleases our Lord, I will take six of them to Your Highnesses when I depart, in order that they may learn our language."[24] Lacking modern weaponry and even metal-forged swords or pikes, he remarked upon their tactical vulnerability, writing, "I could conquer the whole of them with 50 men, and govern them as I pleased."[25]

Columbus also explored the northeast coast of Cuba (landed on 28 October) and the northern coast of Hispaniola, by 5 December. Here, the Santa Maria ran aground on Christmas morning 1492 and had to be abandoned. He was received by the native cacique Guacanagari, who gave him permission to leave some of his men behind. Columbus left 39 men and founded the settlement of La Navidad in what is now present-day Haiti.[26] Before returning to Spain, Columbus also kidnapped some ten to twenty-five natives and took them back with him. Only seven or eight of the native Indians arrived in Spain alive, but they made quite an impression on Seville.[23]

Columbus headed for Spain, but another storm forced him into Lisbon. He anchored next to the King's harbor patrol ship on 4 March 1493 in Portugal. After spending more than one week in Portugal, he set sail for Spain. He crossed the bar of Saltes and entered the harbour of Palos on 15 March 1493. Word of his finding new lands rapidly spread throughout Europe.

There is increasing modern scientific evidence that this voyage also brought syphilis back from the New World. Many of the crew members who served on this voyage later joined the army of King Charles VIII in his invasion of Italy in 1495 resulting in the spreading of the disease across Europe and as many as 5 million deaths.[27][28]

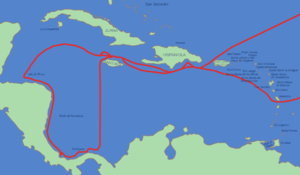

Second voyage

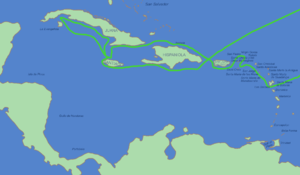

Columbus left Cádiz (modern Spain), on 24 September 1493 to find new territories, with 17 ships carrying supplies, and about 1,200 men to colonize the region. On 13 October the ships left the Canary Islands as they had on the first voyage, following a more southerly course.

On 3 November 1493, Columbus sighted a rugged island that he named Dominica (Latin for Sunday); later that day, he landed at Marie-Galante, which he named Santa Maria la Galante. After sailing past Les Saintes (Los Santos, The Saints), he arrived at Guadeloupe (Santa María de Guadalupe de Extremadura, after the image of the Virgin Mary venerated at the Spanish monastery of Villuercas, in Guadalupe (Spain), which he explored between 4 November and 10 November 1493.

Michele da Cuneo, Columbus’s childhood friend from Savona, sailed with Columbus during the second voyage and wrote: "In my opinion, since Genoa was Genoa, there was never born a man so well equipped and expert in the art of navigation as the said lord Admiral."[29] Columbus named the small island of "Saona ... to honor Michele da Cuneo, his friend from Savona."[30]

The exact course of his voyage through the Lesser Antilles is debated, but it seems likely that he turned north, sighting and naming several islands, including Montserrat (for Santa Maria de Montserrate, after the Blessed Virgin of the Monastery of Montserrat, which is located on the Mountain of Montserrat, in Catalonia, Spain), Antigua (after a church in Seville, Spain, called Santa Maria la Antigua, meaning "Old St. Mary's"), Redonda (for Santa Maria la Redonda, Spanish for "round", owing to the island's shape), Nevis (derived from the Spanish, Nuestra Señora de las Nieves, meaning "Our Lady of the Snows", because Columbus thought the clouds over Nevis Peak made the island resemble a snow-capped mountain), Saint Kitts (for St. Christopher, patron of sailors and travelers), Sint Eustatius (for the early Roman martyr, St. Eustachius), Saba (also for St. Christopher?), Saint Martin (San Martin), and Saint Croix (from the Spanish Santa Cruz, meaning "Holy Cross"). He also sighted the island chain of the Virgin Islands (and named them Islas de Santa Ursula y las Once Mil Virgenes, Saint Ursula and the 11,000 Virgins, a cumbersome name that was usually shortened, both on maps of the time and in common parlance, to Islas Virgenes), and he also named the islands of Virgin Gorda (the fat virgin), Tortola, and Peter Island (San Pedro).

He continued to the Greater Antilles, and landed at Puerto Rico (originally San Juan Bautista, in honor of Saint John the Baptist, a name that was later supplanted by Puerto Rico (English: Rich Port) while the capital retained the name, San Juan) on 19 November 1493. One of the first skirmishes between native Americans and Europeans since the time of the Vikings[31] took place when Columbus's men rescued two boys who had just been castrated by their captors.

On 22 November Columbus returned to Hispaniola, where he intended to visit Fuerte de la Navidad (Christmas Fort), built during his first voyage, and located on the northern coast of Haiti; Fuerte de la Navidad was found in ruins, destroyed by the native Taino people, whereupon, Columbus moved more than 100 kilometers eastwards, establishing a new settlement, which he called La Isabela, likewise on the northern coast of Hispaniola, in the present-day Dominican Republic. However, La Isabela proved to be a poorly chosen location, and the settlement was short-lived.

He left Hispaniola on 24 April 1494, arrived at Cuba (naming it Juana) on 30 April. He explored the southern coast of Cuba, which he believed to be a peninsula rather than an island, and several nearby islands, including the Isle of Pines (Isla de las Pinas, later known as La Evangelista, The Evangelist). He reached Jamaica on May 5. He retraced his route to Hispaniola, arriving on August 20, before he finally returned to Spain.

During his second voyage, Columbus and his men instituted a policy in Hispaniola which has been referred to by numerous historians as genocide.[citation needed] The native Taino people of the island were systematically enslaved and murdered. Hundreds were rounded up and shipped to Europe to be sold; many died en route. For the rest of the population, Columbus demanded that all Taino under his control should bring the Spaniards gold. Those who didn't were to have their hands cut off. Since there was, in fact, little gold to be had, the Taino fled, and the Spaniards hunted them down and killed them. The Taino tried to mount a resistance, but the Spanish weaponry was superior, and European diseases ravaged their population. In despair, the Taino engaged in mass suicide, even killing their own children to save them from the Spaniards. Within two years, half of what may have been 250,000 Taino were dead. The remainder were taken as slaves and set to work on plantations, where the mortality rate was very high. By 1550, 60 years after Columbus landed, only a few hundred Taino were left on their island. In another hundred years, perhaps only a handful remained.[32][33][34][35]

Third voyage

On 30 May 1498, Columbus left with six ships from Sanlúcar, Spain, for his third trip to the New World. He was accompanied by the young Bartolomé de Las Casas, who would later provide partial transcripts of Columbus's logs.

Columbus led the fleet to the Portuguese island of Porto Santo, his wife's native land. He then sailed to Madeira and spent some time there with the Portuguese captain João Gonçalves da Camara before sailing to the Canary Islands and Cape Verde. Columbus landed on the south coast of the island of Trinidad on 31 July. From 4 August through 12 August he explored the Gulf of Paria which separates Trinidad from Venezuela. He explored the mainland of South America, including the Orinoco River. He also sailed to the islands of Chacachacare and Margarita Island and sighted and named Tobago (Bella Forma) and Grenada (Concepcion).

Columbus returned to Hispaniola on 19 August to find that many of the Spanish settlers of the new colony were discontented, having been misled by Columbus about the supposedly bountiful riches of the new world. An entry in his journal from September 1498 reads, "From here one might send, in the name of the Holy Trinity, as many slaves as could be sold..." Indeed, as a fierce supporter of slavery, Columbus ultimately refused to baptize the native people of Hispaniola, since Catholic law forbade the enslavement of Christians.[36]

Columbus repeatedly had to deal with rebellious settlers and natives. [citation needed] He had some of his crew hanged for disobeying him. A number of returning settlers and sailors lobbied against Columbus at the Spanish court, accusing him and his brothers of gross mismanagement. On his return he was arrested for a period (see Governorship and arrest section below).

Fourth voyage

Columbus made a fourth voyage nominally in search of the Strait of Malacca to the Indian Ocean. Accompanied by his brother Bartolomeo and his 13-year-old son Fernando, he left Cádiz, (modern Spain), on 11 May 1502, with the ships Capitana, Gallega, Vizcaína and Santiago de Palos. He sailed to Arzila on the Moroccan coast to rescue Portuguese soldiers whom he had heard were under siege by the Moors. On June 15, they landed at Carbet on the island of Martinique (Martinica). A hurricane was brewing, so he continued on, hoping to find shelter on Hispaniola. He arrived at Santo Domingo on 29 June but was denied port, and the new governor refused to listen to his storm prediction. Instead, while Columbus's ships sheltered at the mouth of the Rio Jaina, the first Spanish treasure fleet sailed into the hurricane. Columbus's ships survived with only minor damage, while twenty-nine of the thirty ships in the governor's fleet were lost to the 1 July storm. In addition to the ships, 500 lives (including that of the governor, Francisco de Bobadilla) and an immense cargo of gold were surrendered to the sea.

After a brief stop at Jamaica, Columbus sailed to Central America, arriving at Guanaja (Isla de Pinos) in the Bay Islands off the coast of Honduras on 30 July. Here Bartolomeo found native merchants and a large canoe, which was described as "long as a galley" and was filled with cargo. On 14 August he landed on the American mainland at Puerto Castilla, near Trujillo, Honduras. He spent two months exploring the coasts of Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, before arriving in Almirante Bay, Panama on 16 October.

On 5 December 1502, Columbus and his crew found themselves in a storm unlike any they had ever experienced. In his journal Columbus writes,

For nine days I was as one lost, without hope of life. Eyes never beheld the sea so angry, so high, so covered with foam. The wind not only prevented our progress, but offered no opportunity to run behind any headland for shelter; hence we were forced to keep out in this bloody ocean, seething like a pot on a hot fire. Never did the sky look more terrible; for one whole day and night it blazed like a furnace, and the lightning broke with such violence that each time I wondered if it had carried off my spars and sails; the flashes came with such fury and frightfulness that we all thought that the ship would be blasted. All this time the water never ceased to fall from the sky; I do not say it rained, for it was like another deluge. The men were so worn out that they longed for death to end their dreadful suffering.[37]

In Panama, Columbus learned from the natives of gold and a strait to another ocean. After much exploration, in January 1503 he established a garrison at the mouth of the Rio Belen. On 6 April one of the ships became stranded in the river. At the same time, the garrison was attacked, and the other ships were damaged (Shipworms also damaged the ships in tropical waters.[38]). Columbus left for Hispaniola on 16 April heading north. On 10 May he sighted the Cayman Islands, naming them "Las Tortugas" after the numerous sea turtles there. His ships next sustained more damage in a storm off the coast of Cuba. Unable to travel farther, on 25 June 1503, they were beached in St. Ann's Bay, Jamaica.

For a year Columbus and his men remained stranded on Jamaica. A Spaniard, Diego Mendez, and some natives paddled a canoe to get help from Hispaniola. That island's governor, Nicolás de Ovando y Cáceres, detested Columbus and obstructed all efforts to rescue him and his men. In the meantime Columbus, in a desperate effort to induce the natives to continue provisioning him and his hungry men, successfully intimidated the natives by correctly predicting a lunar eclipse for 29 February 1504, using the Ephemeris of the German astronomer Regiomontanus.[39] Help finally arrived, no thanks to the governor, on 29 June 1504, and Columbus and his men arrived in Sanlúcar, Spain, on 7 November.

Governorship and arrest

During Columbus's stint as governor and viceroy, he had been accused of governing tyrannically. Columbus was physically and mentally exhausted; his body was wracked by arthritis and his eyes by ophthalmia. In October 1499, he sent two ships to Spain, asking the Court of Spain to appoint a royal commissioner to help him govern.

The Court appointed Francisco de Bobadilla, a member of the Order of Calatrava; however, his authority stretched far beyond what Columbus had requested. Bobadilla was given total control as governor from 1500 until his death in 1502. Arriving in Santo Domingo while Columbus was away, Bobadilla was immediately peppered with complaints about all three Columbus brothers: Christopher, Bartolomé, and Diego. Consuelo Varela, a Spanish historian, states: "Even those who loved him [Columbus] had to admit the atrocities that had taken place."[40][41]

As a result of these testimonies and without being allowed a word in his own defense, Columbus, upon his return, had manacles placed on his arms and chains on his feet and was cast into prison to await return to Spain. He was 53 years old.

On 1 October 1500, Columbus and his two brothers, likewise in chains, were sent back to Spain. Once in Cádiz, a grieving Columbus wrote to a friend at court:

It is now seventeen years since I came to serve these princes with the Enterprise of the Indies. They made me pass eight of them in discussion, and at the end rejected it as a thing of jest. Nevertheless I persisted therein... Over there I have placed under their sovereignty more land than there is in Africa and Europe, and more than 1,700 islands... In seven years I, by the divine will, made that conquest. At a time when I was entitled to expect rewards and retirement, I was incontinently arrested and sent home loaded with chains... The accusation was brought out of malice on the basis of charges made by civilians who had revolted and wished to take possession on the land....

I beg your graces, with the zeal of faithful Christians in whom their Highnesses have confidence, to read all my papers, and to consider how I, who came from so far to serve these princes... now at the end of my days have been despoiled of my honor and my property without cause, wherein is neither justice nor mercy.[43]

According to testimony of 23 witnesses during his trial, Columbus regularly used barbaric acts of torture to govern Hispaniola.[36]

Columbus and his brothers lingered in jail for six weeks before busy King Ferdinand ordered their release. Not long after, the king and queen summoned the Columbus brothers to the Alhambra palace in Granada. There the royal couple heard the brothers' pleas; restored their freedom and wealth; and, after much persuasion, agreed to fund Columbus' fourth voyage. But the door was firmly shut on Columbus' role as governor. Henceforth Nicolás de Ovando y Cáceres was to be the new governor of the West Indies.

Later life

While Columbus had always given the conversion of non-believers as one reason for his explorations, he grew increasingly religious in his later years. He claimed to hear divine voices, lobbied for a new crusade to capture Jerusalem, often wore Franciscan habit, and described his explorations to the "paradise" as part of God's plan which would soon result in the Last Judgment and the end of the world.[citation needed]

In his later years, Columbus demanded that the Spanish Crown give him 10% of all profits made in the new lands, pursuant to earlier agreements. Because he had been relieved of his duties as governor, the crown did not feel bound by these contracts, and his demands were rejected. After his death, his family sued in the pleitos colombinos for part of the profits from trade with America.

On 20 May 1506, at about age 55, Columbus died in Valladolid, fairly wealthy from the gold his men had accumulated in Hispaniola. At his death, he was still convinced that his journeys had been along the east coast of Asia. According to a study, published in February 2007, by Antonio Rodriguez Cuartero, Department of Internal Medicine of the University of Granada, he died of a heart attack caused by Reiter's Syndrome (also called reactive arthritis). According to his personal diaries and notes by contemporaries, the symptoms of this illness (burning pain during urination, pain and swelling of the knees, and conjunctivitis) were clearly evident in his last three years.[44]

Columbus' remains were first interred at Valladolid, then at the monastery of La Cartuja in Seville (southern Spain) by the will of his son Diego, who had been governor of Hispaniola. In 1542 the remains were transferred to Santo Domingo, in eastern Hispaniola. In 1795 the French took over Hispaniola, and the remains were moved to Havana, Cuba. After Cuba became independent following the Spanish-American War in 1898, the remains were moved back to Spain, to the Cathedral of Seville,[45] where they were placed on an elaborate catafalque.

However, a lead box bearing an inscription identifying "Don Christopher Columbus" and containing bone fragments and a bullet was discovered at Santo Domingo in 1877.

To lay to rest claims that the wrong relics had been moved to Havana and that Columbus' remains had been left buried in the cathedral at Santo Domingo, DNA samples were taken in June 2003 (History Today August 2003). The results are not conclusive. Initial observations suggested that the bones did not appear to belong to somebody with the physique or age at death associated with Columbus.[46] DNA extraction proved difficult; only a few limited fragments of mitochondrial DNA could be isolated. However, such as they are, these do appear to match corresponding DNA from Columbus's brother, giving support to the idea that the two had the same mother and that the body therefore may be that of Columbus.[47][48] The authorities in Santo Domingo have not allowed the remains there to be exhumed, so it is unknown if any of those remains could be from Columbus's body. The location of the Dominican remains is in "the Colombus Lighthouse" or Faro a Colón which is in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic.

Legacy

Although among non-Native Americans Christopher Columbus is traditionally considered the discoverer of America, Columbus was preceded by the various cultures and civilizations of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, as well as the Western world's Vikings at L'Anse aux Meadows. He is regarded more accurately as the person who brought the Americas into the forefront of Western attention. "Columbus' claim to fame isn't that he got there first," explains historian Martin Dugard, "it's that he stayed."[49] The popular idea that he was first person to envision a rounded earth is false. The rounded shape of the earth has already been known in ancient times. Jeffrey Russell states that the modern view that people of the Middle Ages believed that the Earth was flat is said to have entered the popular imagination in the 19th century, thanks largely to the publication of Washington Irving's fantasy The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus in 1828.[50] By Columbus's time, educated men were in agreement as to its spherical shape, even if many people believed otherwise. More contentious was the size of the earth, and whether it was possible in practical terms to cross such a vast body of water: the longest any ship (European or otherwise) had gone without making landfall did not much exceed 30 days when Columbus embarked on his first audacious voyage lasting 36 days across the Atlantic Ocean (from the Canari Islands).

Amerigo Vespucci's travel journals, published 1502-4, convinced Martin Waldseemüller that the discovered place was not India, as Columbus always believed, but a new continent, and in 1507, a year after Columbus's death, Waldseemüller published a world map calling the new continent America from Vespucci's Latinized name "Americus".

Historically the British had downplayed Columbus and emphasized the role of the Venetian John Cabot as a pioneer explorer; but for the emerging United States, Cabot made a poor national hero. Veneration of Columbus in America dates back to colonial times. The name Columbia for "America" first appeared in a 1738 weekly publication of the debates of the British Parliament.[51] The use of Columbus as a founding figure of New World nations and the use of the word 'Columbia', or simply the name 'Columbus', spread rapidly after the American Revolution. In 1812, the name 'Columbus' was given to the newly founded capitol of Ohio. During the last two decades of the 18th century the name "Columbia" was given to the federal capital District of Columbia, South Carolina's new capital city, Columbia, South Carolina, the Columbia River, and numerous other places. Attempts to rename the United States "Columbia" failed, but Columbia became a female national personification of America, similar to the male Uncle Sam.[citation needed] Outside the United States the name was used in 1819 for the Gran Colombia, a precursor of the modern Republic of Colombia. The main plaza in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico is called Plaza Colón in honor of the Admiral.[52][53]

A candidate for sainthood in the Catholic Church in 1866, Celebration of Columbus's legacy perhaps reached a zenith in 1892 when the 400th anniversary of his first arrival in the Americas occurred. Monuments to Columbus like the Columbian Exposition in Chicago were erected throughout the United States and Latin America extolling him. Numerous cities, towns, counties, and streets have been named after him, including the capital cities of two U.S. states, Ohio and South Carolina.

In 1909, descendants of Columbus undertook to dismantle the Columbus family chapel in Spain and move it to a site near State College, Pennsylvania, where it may now be visited by the public. At the museum associated with the chapel, there are a number of Columbus relics worthy of note, including the armchair which the "Admiral of the Ocean Sea" used at his chart table.

Physical appearance

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2009) |

Although an abundance of artwork involving Christopher Columbus exists, no authentic contemporary portrait has been found.[54] Sometime between 1505 and 1536, Alejo Fernández painted an altarpiece, The Virgin of the Navigators, that includes a depiction of Columbus. The painting was commissioned for a chapel in Seville's Casa de Contratación (House of Trade) and remains there to this day.[citation needed] James W. Loewen, author of Lies My Teacher Told Me, said that the various posthumous portraits have no historical value.[55]

At the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, 71 alleged portraits of Columbus were displayed, most did not match contemporary descriptions.[56] These writings describe him as having reddish hair, which turned to white early in his life, light colored eyes,[57] as well as being a lighter skinned person with too much sun exposure turning his face red.

In keeping with descriptions of Columbus having had auburn hair or (later) white hair, some textbooks use the Sebastiano del Piombo painting (which in its normal-sized resolution shows Columbus's hair as auburn) so often that it has become the iconic image of Columbus accepted by popular culture. Accounts consistently describe Columbus as a large and physically strong man of some six feet or more in height, easily taller than the average European of his day.[58]

In popular culture

Columbus is a significant historical figure and has been depicted in fiction and in popular films and television.

In 1991, author Salman Rushdie published a fictional representation of Columbus in The New Yorker, "Christopher Columbus and Queen Isabella of Spain Consummate Their Relationship, Santa Fe, January, 1492," (The New Yorker, 17 June 1991, p. 32). In Pastwatch: The Redemption of Christopher Columbus (1996) science fiction novelist Orson Scott Card focuses on Columbus's life and activities, but the novel's action also deals with a group of scientists from the future who travel back to the 15th century with the goal of changing the pattern of European contact with the Americas. British author Stephen Baxter includes Columbus's quest for royal sponsorship as a crucial historical event in his 2007 science fiction novel Navigator (ISBN 978-0-441-01559-7), the third entry in the author's Time's Tapestry Series. American author Mark Twain based the time traveller's trick in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court on Columbus's successful prediction of a lunar eclipse on his fourth voyage to the new world.

Columbus has also been portrayed in cinema and television, including mini-series, films and cartoons. Most notably he was portrayed by Gérard Depardieu in 1992 film by Ridley Scott 1492: Conquest of Paradise. Scott presented Columbus as a forward thinking idealist as opposed to the view that he was ruthless and responsible for the misfortune of Native Americans.

Other productions include TV mini-series Christopher Columbus (1985) with Gabriel Byrne as Columbus, Christopher Columbus: The Discovery, a 1992 biopic film by Alexander Salkind, Christopher Columbus, a 1949 film starring Fredric March as Columbus, and comedy Carry On Columbus (1992).

Christopher Columbus appears as a Great Explorer in the 2008 strategy video game Civilization Revolution.[59]

Notes

- ^ "Parks Canada — L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site of Canada". Pc.gc.ca. 2009-04-24. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (2003). "1". A People's History of the United States: 1492-Present (Fifth Printing ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. p. 7. ISBN 0060838655.

- ^ Churchill, Ward (December 1993). Indians Are Us?: Culture and Genocide in Native North America. Common Courage Press. Retrieved 10-12-2009.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Rouse, Irving (July 28, 1993). The Tainos: Rise and Decline of the People Who Greeted Columbus (Paperback). Yale University Press. ISBN 0300056966.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (2003). "1". A People's History of the United States: 1492-Present (Fifth Printing ed.). Harper Perennial. p. 5. ISBN 0060838655.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (2003). "1". A People's History of the United States: 1492-Present (Fifth Printing ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. p. 4.

- ^ Rime diverse, Pavia, 1595, p.117

- ^ Ra Gerusalemme deliverâ, Genoa, 1755, XV-32

- ^ Phillips, William D., and Carla Rahn Phillips. The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. Page 9.

"Even with less than a complete record, however, scholars can state with assurance that Columbus was born in the republic of Genoa in northern Italy, although perhaps not in the city itself, and that his family made a living in the wool business as weavers and merchants...The two main early biographies of Columbus have been taken as literal truth by hundreds of writers, in large part because they were written by individual closely connected to Columbus or his writings. ...Both biographies have serious shortcomings as evidence." - ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, 1993 ed., Vol. 16, pp. 605ff / Morison, Christopher Columbus, 1955 ed., pp. 14ff

- ^ "Christopher Columbus Biography Page 2". Columbus-day.123holiday.net. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ "Marco Polo et le Livre des Merveilles", ISBN 9782354040079 p.37

- ^ Boller, Paul F (1995). Not So!:Popular Myths about America from Columbus to Clinton. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195091861.

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey Burton 1991. Inventing the Flat Earth. Columbus and modern historians, Praeger, New York, Westport, London 1991;

Zinn, Howard 1980. A People's History of the United States, HarperCollins 2001. p.2 - ^ a b Sagan, Carl. Cosmos; the mean circumference of the Earth is 40,041.47 km.

- ^ a b Morison, Samuel Eliot, Admiral of the Ocean Sea: The Life of Christopher Columbus Boston, 1942

- ^ "The First Voyage Log". Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ^ "Christopher Columbus and the Spanish Empire". Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ^ "Trade Winds and the Hadley Cell". Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ^ Durant, Will "The Story of Civilization" vol. vi, "The Reformation". Chapter XIII, page 260.

- ^ Mark McDonald, "Ferdinand Columbus, Renaissance Collector (1488-1539)", 2005, British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714126449

- ^ The Columbus Foundation: Santa Clara[dead link]

- ^ a b Clements R. Markham, ed. The Journal of Christopher Columbus (During His First Voyage). ASIN B000I1OMXM.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "Hakluyt Society (1893)" ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "book2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Robert H. Fuson, ed The Log of Christopher Columbus, Tab Books, 1992, International Marine Publishing, ISBN 0-87742-316-4

- ^ "Columbus Day sparks debate over explorer's legacy".

- ^ Maclean, Frances (2008). "The Lost Fort of Columbus". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ CBC News Staff (2008). "Study traces origins of syphilis in Europe to New World". Retrieved 2008-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Harper, Kristin; et al. (2008). "On the Origin of the Treponematoses: A Phylogenetic Approach". Retrieved 2008-01-21.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Felipe Fernández-Armesto, Columbus, Oxford Univ. Press, (1991) pp. 103-104

- ^ Paolo Emilio Taviani, Columbus the Great Adventure, Orion Books, New York (1991) p. 185

- ^ Phillips, Jr., William D. & Carla Rahn Phillips (1992). The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521350976.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Christopher Columbus and the Indians by Howard Zinn". Newhumanist.com. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ^ "Jack Weatherford, Examining the reputation of Christopher Columbus". Hartford-hwp.com. 2001-04-20. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ "9.11 - Columbus' History of Genocide". Web.mit.edu. 1991-10-12. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ "Pre-Columbian Hispaniola — Arawak/Taino Indians". Hartford-hwp.com. 2001-09-15. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ a b Who really sailed the ocean blue in 1492?, Christian Science Monitor, 17 October 2006

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot,Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus, Boston, 1942, page 617.

- ^ The History Channel. Columbus: The Lost Voyage.

- ^ Samuel Eliot Morison, Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus, 1942, pp. 653–54. Samuel Eliot Morison, Christopher Columbus, Mariner, 1955, pp. 184-92.

- ^ Giles Tremlett (2006-08-07). "Lost document reveals Columbus as tyrant of the Caribbean". The Guardian. Retrieved 2006-10-10.

- ^ Bobadilla's 48-page report—derived from the testimonies of 23 people who had seen or heard about the treatment meted out by Columbus and his brothers—had originally been lost for centuries, but was rediscovered in 2005 in the Spanish archives in Valladolid. It contained an account of Columbus's seven-year reign as the first Governor of the Indies.

- ^ The Brooklyn Museum catalogue notes that the most likely source for Leutze's trio of Columbus paintings is Washington Irving’s best-selling Life and Voyages of Columbus (1828).

- ^ Samuel Eliot Morison, Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus, p. 576.

- ^ "Cause of the death of Columbus (in Spanish)". Eluniversal.com.mx. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ "''Cristóbal Colón: traslación de sus restos mortales a la ciudad de Sevilla'' at Fundación Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes". Cervantesvirtual.com. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ Giles Tremlett, Young bones lay Columbus myth to rest, The Guardian, August 11, 2004

- ^ Lorenzi, Rossella (October 6, 2004). "DNA Suggests Columbus Remains in Spain". Discovery News. Retrieved 2006-10-11.

- ^ DNA verifies Columbus’ remains in Spain, Associated Press, May 19, 2006

- ^ Dugard, Martin. The Last Voyage of Columbus. Little, Brown and Company: New York, 2005.

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey B. "The Myth of the Flat Earth". American Scientific Affiliation. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ The Gentleman's Magazine, Vol. 8, June 1738, p. 285

- ^ "Plaza Colón" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ^ Rigau, Jorge (2009). Puerto Rico Then and Now. San Diego, California: Thunder Bay Press. pp. 74–75.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Alden, Henry Mills. Harper's New Monthly Magazine. Volume 84, Issues 499-504. Published by Harper & Brothers, 1892. Originally from Harvard University. Digitized on December 16, 2008. 732. Retrieved on September 8, 2009. 'Major, Int. Letters of Columbus, ixxxviii., says "Not one of the so-called portraits of Columbus is unquestionably authentic." They differ from each other, and cannot represent the same person.'

- ^ Loewen, James W. Lies My Teacher Told Me. 1st Touchstone ed, Simon & Schuster, 1996. ISBN 0684818868. 55.

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus, pg. 47-48, Boston 1942.

- ^ Bartolomé de Las Casas, Historia de las Indias, ed. Agustín Millares Carlo, 3 vols. (Mexico City, 1951), book 1, chapter 2, 1:29. The Spanish word garzos is now usually translated as "light blue," but it seems to have connoted light grey-green or hazel eyes to Columbus's contemporaries. The word rubio can mean "blonde," "fair," or "ruddy." The Worlds of Christopher Columbus by William D. & Carla Rahn Phillips, pg. 282.

- ^ "DNA Tests on the bones of Christopher Columbus' bones, on his relatives and on Genoese and Catalin claimaints". Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ^ Civilization Revolution: Great People "CivFanatics" Retrieved on 4th September 2009

See also

- 1492: Conquest of Paradise, a 1992 biopic film by Ridley Scott

- Origin theories of Christopher Columbus

- Christopher Columbus: The Discovery, a 1992 biopic film by Alexander Salkind

- Christopher Columbus, a 1949 film starring Fredric March as Columbus

- List of Viceroys of New Spain

- Viceroyalty of New Spain

- Bartolomeo Columbus

- Columbus Day

- Colombia, South American country named in honor of Christopher Columbus

- Fernando Colón

- Guanahani (a discussion of candidates for site of first landing)

- Knights of Columbus

- The Last Voyage of Columbus (book)

- List of places named for Christopher Columbus

- Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli

- Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact

- Rafael Perestrello

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

- Egg of Columbus

References

- Cohen, J.M. (1969) The Four Voyages of Christopher Columbus: Being His Own Log-Book, Letters and Dispatches with Connecting Narrative Drawn from the Life of the Admiral by His Son Hernando Colon and Others. London UK: Penguin Classics.

- Cook, Sherburn and Woodrow Borah (1971) Essays in Population History, Volume I. Berkeley CA: University of California Press

- Crosby, A. W. (1987) The Columbian Voyages: the Columbian Exchange, and their Historians. Washington, DC: American Historical Association.

- Davidson, Miles H. (1997) Columbus Then and Now: A Life Reexamined, Norman and London, University of Oklahoma Press.

- Fuson, Robert H. (1992) The Log of Christopher Columbus. International Marine Publishing

- Hart, Michael H. (1992) The 100. Seacaucus NJ: Carol Publishing Group.

- Keen, Benjamin (1978) The Life of the Admiral Christopher Columbus by his Son Ferdinand, Westport CT: Greenwood Press.

- Loewen, James. Lies My Teacher Told Me

- Morison, Samuel Eliot, Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus, Boston, Little, Brown and Company, 1942.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot, Christopher Columbus, Mariner, Boston, Little, Brown and Company, 1955.

- Phillips, W. D. and C. R. Phillips (1992) The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Turner, Jack (2004) Spice: The History of a Temptation. New York: Random House.

- Wilford, John Noble (1991) The Mysterious History of Columbus: An Exploration of the Man, the Myth, the Legacy. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

External links

- Christopher Columbus Fountain, Kenosha, Wisconsin (Michael Martino, sculptor)

- The Letter of Columbus to Luis de Sant Angel Announcing His Discovery

- Podcasts and audio about Columbus

- Columbus Navigation

- Images of Christopher Columbus and His Voyages Selections from the Collections of the Library of Congress.

- Works by Christopher Columbus at Project Gutenberg

- The Eclipse That Saved Columbus Science News October 7, 2006

- Christopher Columbus and the Indians By Howard Zinn, from A People's History of the United States

- Columbus in the Bay of Pigs a historical poem about Columbus's invasion and Indigenous resistance

- Explorer Columbus 'named Pedro Scotto'

Films

- Animated Hero Classics: Christopher Columbus (1991) at IMDb

- 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992) at IMDb

Sister projects

![]() Quotations related to Christopher Columbus at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Christopher Columbus at Wikiquote

![]() Media related to Christopher Columbus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Christopher Columbus at Wikimedia Commons

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)