Genesis creation narrative: Difference between revisions

Aunt Entropy (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 24.63.185.134 (talk) to last version by Lisa |

Slrubenstein (talk | contribs) putting in mainstrean scholarly view |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

| row3= [[Book of Genesis]] in the [[Bible]].}} |

| row3= [[Book of Genesis]] in the [[Bible]].}} |

||

The '''Genesis creation narrative''', found in the first two chapters of the [[Book of Genesis]] in the [[Bible]], is one of several [[Ancient Near East]] [[creation myth]]s, differing from the others in |

The '''Genesis creation narrative''', found in the first two chapters of the [[Book of Genesis]] in the [[Bible]], is one of several [[Ancient Near East]] [[creation myth]]s, differing from the others in the deliberation with which God creates the world<ref>Yehezkiel Kaufmann ''The Religion of Israel, from Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile'' (1960) University of Chicago Press</ref> It is part of the [[Biblical canon|biblical canons]] of [[Judaism]] and [[Christianity]],<ref>{{harvnb|Leeming|2004}} - "Although it is canonical for both Christians and Jews, and in part for followers of Islam, different emphases are placed on the story by the three religions."</ref> and describes the beginning of the earth and life, and the creation of humanity in the [[image of God]]. |

||

== Overview == |

== Overview == |

||

Revision as of 01:32, 10 May 2010

Editing of this article by new or unregistered users is currently disabled until July 26, 2025 at 16:43 UTC, or until editing disputes have been resolved. This protection is not an endorsement of the current version. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. If you cannot edit this article and you wish to make a change, you can submit an edit request, discuss changes on the talk page, request unprotection, log in, or create an account. |

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

The Genesis creation narrative, found in the first two chapters of the Book of Genesis in the Bible, is one of several Ancient Near East creation myths, differing from the others in the deliberation with which God creates the world[1] It is part of the biblical canons of Judaism and Christianity,[2] and describes the beginning of the earth and life, and the creation of humanity in the image of God.

Overview

The opening passages of the Book of Genesis consecutively contain two creation stories. In the first story God progressively creates the different features of the world over a series of six days, resting on the seventh day.[3] Creation is performed by divine incantation: on the first day God says "Let there be light!" and light appears. On the second day God creates an expanse (firmament) to separate the waters above (the sky) from those below (the ocean/abyssos). On the third day God commands the waters below to recede and make dry land appear, and fills the earth with vegetation. God then puts lights in the sky to separate day from night to mark the seasons. On the fifth day, God creates sea creatures and birds of every kind and commands them to procreate. On the sixth day, God creates land creatures of every kind. Man and woman are created last, after the entire world is prepared for them; they are created in the image of God, and are given dominion and care over all other created things. God rests on the seventh and final day of creation, which he marks as holy.

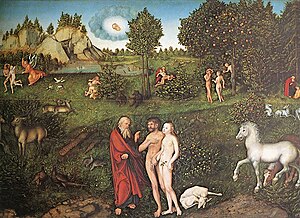

In the second story the creation of man follows the creation of the heavens and earth, but occurs before the creation of plants and animals.[4] God takes dust from the ground to form a man and breathes life into him. God prepares a garden in the East of Eden and puts the man there, then fills it with trees bearing fruit for him to eat. The man is invited to eat the fruit of any tree but one: the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. God commands man not to eat of that one tree "for when you eat of it you will surely die."[5] Birds and animals are then created as man's companions and helpers, and God presents them to the man. The first man gives names to each one, but finds none suitable to be his helper, so God puts him into a deep sleep and removes one of his ribs, which he uses to make the first woman. "For this reason," the text reads, "a man will leave his father and mother for his wife, and they shall be joined as one flesh."

The narratives

The passages have had an exceptionally long and complex history of interpretation. Until the latter half of the 19th century, they were seen as one continuous, uniform story with Genesis 1:1–2:3 outlining the world's origin, and 2:4–2:25 carefully painting a more detailed picture of the creation of humanity. Modern scholarship, persuaded by (1) the use of two different names for God, (2) two different emphases (physical vs. moral issues), and (3) a different order of creation (plants before humans vs. plants after humans), advances that these are two distinct scriptures written many years apart by two different sources.[citation needed]

Prologue

Genesis 1:1–2 (see main articles Ex nihilo and Chaos.)

The prologue has traditionally been seen as an indeterminate moment when God created both space and time ex nihilo (out of nothing)[6] or out of primordial waters/chaos.[7][8]

Gordon Wenham presents four possible ways to translate these verses:[9]

- Verse 1 is a temporal clause subordinate to the main clause in v. 2.

- Verse 1 is a temporal clause subordinate to the main clause in v. 3.

- Verse 1 is a main clause, summarizing all the events described in vv. 2-31.

- Verse 1 is a main clause describing the first act of creation. Verses 2 and 3 describe subsequent phases in God's creative activity.

The fourth view is the traditional view and remains the most common in modern English Bible translations. According to this view, the prologue forms the basis for all subsequent creation. It summarizes the entire first creation narrative, allowing the presupposition of "the existence of matter, of raw material for God to use'.[8] Chaos then is not the precursor of creation, as in Babylonian myths, but the result. Therefore the Genesis creation narrative does not merely repeat or demythologize oriental creation myths, but it appears to purposefully set out from the beginning to repudiate them.[10]

Theologians within the Judaeo-Christian tradition such as Philo,[11][12] Augustine,[13] John Calvin,[14] John Wesley,[15] and Matthew Henry,[16] believe that pre-creation is being described. Philo believed that the origins of the universe stem from the ideas of God which eventually are used as the pattern for the creation of the material universe described in the later verses. The creation of material objects starts with the idea of the object and then the idea is transformed into reality:

For God, as apprehending beforehand, as a God must do, that there could not exist a good imitation without a good model, and that of the things perceptible to the external senses nothing could be faultless which was not fashioned with reference to some archetypal idea conceived by the intellect, when he had determined to create this visible world, previously formed that one which is perceptible only by the intellect, in order that so using an incorporeal model formed as far as possible on the image of God, he might then make this corporeal world, a younger likeness of the elder creation, which should embrace as many different genera perceptible to the external senses, as the other world contains of those which are visible only to the intellect.

— Philo—On the Creation (16)

Philo also believed that time is a result of space (universe/world) and that God created space, which resulted in time also being created either simultaneously with space or immediately thereafter.[11] See main article spacetime.

First narrative: creation week

The first narrative, Genesis 1:1–2:3, begins with the indeterminate period in which God creates the heavens and the earth[17] out of nothing (ex nihilo)[6] or out of primordial waters/chaos.[7] Next it describes the transformation of creation in six days from chaos to a state of order that culminates with God's creation of two humans in his own image. The seventh day is sanctified by God as a day of rest (Sabbath).

The remainder of the creation narrative more closely parallels the Mesopotamian accounts, detailing the formation of unique features out of a separation of waters, an understanding reflected even in the New Testament 2 Pet 3:4–7 in which it is understood that "earth was formed out of water and by water."[7] Jungian mythologists, such as Joseph Campbell, find this creation out of water to be a possible holdover from neolithic matriarchal goddess religions, in which the universe is not created, but born (i.e., the water as amniotic fluid).[18]

The creation week narrative consists of eight divine commands executed over six days, followed by a seventh day of rest.

- First day: God creates light ("Let there be light!")Gen 1:3—the first divine command. The light is divided from the darkness, and "day" and "night" are named.

- Second day: God creates a firmament ("Let a firmament be...!")Gen 1:6–7—the second command—to divide the waters above from the waters below. The firmament is named "skies".

- Third day: God commands the waters below to be gathered together in one place, and dry land to appear (the third command).Gen 1:9–10 "earth" and "sea" are named. God commands the earth to bring forth grass, plants, and fruit-bearing trees (the fourth command).

- Fourth day: God creates lights in the firmament (the fifth command)Gen 1:14–15 to separate light from darkness and to mark days, seasons and years. Two great lights are made (most likely the Sun and Moon, but not named), and the stars.

- Fifth day: God commands the sea to "teem with living creatures", and birds to fly across the heavens (sixth command)Gen 1:20–21 He creates birds and sea creatures, and commands them to be fruitful and multiply.

- Sixth day: God commands the land to bring forth living creatures (seventh command);Gen 1:24–25 He makes wild beasts, livestock and reptiles. He then creates humanity in His "image" and "likeness" (eighth command).Gen 1:26–28 They are told to "be fruitful, and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue it." Humans and animals are given plants to eat. The totality of creation is described by God as "very good."

- Seventh day: God, having completed the heavens and the earth, rests from His work, and blesses and sanctifies the seventh day.

Literary bridge

Genesis 2:4 "These are the generations of the heavens and the earth when they were created."

This verse lies between the creation week account and the account of Eden which follows. Its significance is found in that it is the first of ten tôledôt ("generation") phrases used throughout the book of Genesis, which provide a literary structure to the book.[19] Since the phrase always precedes the "generation" to which it belongs, the "generations of the heavens and the earth" should logically be taken to refer to Genesis 2; a position taken by most commentators.[20] Nevertheless, Rashi argues that in this case it should apply to what precedes.[21]

Second narrative: Eden

The second narrative in Genesis 2:4–2:25 tells of God forming the first man (Adam) from dust, then planting a garden, then forming animals and birds for Adam to name, and finally, creating the first woman, Eve, to be his wife. The two narratives are linked by a short bridge[17] and form part of a wider narrative unit in Genesis labeled by some scholars as the primeval story.[22]

This second creation account in Genesis is thought to be much older, and reflects a different historical and literary context.[23] Its presentation uses imagery reflective of the ancient pastoral shepherding tradition of Israel.[23] The Eden narrative addresses the creation of the first man and woman:

- Genesis 2:4b—the second half of the bridge formed by the "generations" formula, and the beginning of the Eden narrative—places the events of the narrative "in the day when YHWH Elohim made the earth and the heavens...."[24]

- Before any plant had appeared, before any rain had fallen, while a mist[25] watered the earth, Yahweh formed the man (Heb. ha-adam הָאָדָם) out of dust from the ground (Heb. ha-adamah הָאֲדָמָה), and breathed the breath of life into his nostrils. And the man became a "living being" (Heb. nephesh).

- Yahweh planted a garden in Eden and he set the man in it. He caused pleasant trees to sprout from the ground, and trees necessary for food, also the tree of life and the tree of knowledge of good and evil. Some modern translations alter the tense-sequence so that the garden is prepared before the man is set in it, but the Hebrew has the man created before the garden is planted. An unnamed river is described: it goes out from Eden to water the garden, after which it parts into four named streams. He takes the man who is to tend His garden and tells him he may eat of the fruit of all the trees except the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, "for in that day thou shalt surely die."

- Yahweh resolved to make a "helper"[26] suitable for (lit. "corresponding to")[27] the man.[28] He made domestic animals and birds, and the man gave them their names, but none of them was a fitting helper. Therefore, Yahweh caused the man to sleep, and he took a rib,[29] and from it formed a woman. The man then named her "Woman" (Heb. ishah), saying "for from a man (Heb. ish) has this been taken." A statement instituting marriage follows: "Therefore shall a man leave his father and his mother, and shall cleave unto his wife: and they shall be one flesh." The lack of punctuation in the Hebrew makes it uncertain whether or not these words about marriage are intended to be a continuation of the speech of the man.

- The man and his wife were naked, and felt no shame.

Biblical creation narratives outside of Genesis 1-2

Descriptions of creation abound throughout the Bible. The Harper's Bible dictionary writes that, "Divine struggle with waters, victory over chaos, and cosmogonic promulgation of law/wisdom are found throughout biblical poetry."[30] For some examples of this in the Old Testament, see, Job 38–41; Psalms 18, 19, 24; 24; 33; 68; 93; 95; 104; Proverbs 8:22–33; Isaiah 40–42. In the New Testament, see, John 1; Colossians 1; Hebrews 3; 8.

Structure and composition

Structure

Genesis 1 consists of an indeterminate time period that God created space and time ex nihilo (out of nothing)[6] followed by eight acts of creation within a six day framework. During the indeterminate time period described in verses 1 and 2 there is no division in time. In each of the first three days there is an act of division: Day one divides the darkness from light; day two, the waters from the skies; and day three, the sea from the land. In each of the next three days these divisions are populated: day four populates what was created on day one, and heavenly bodies are placed in the darkness and light; day five populates what was created on day two, and fish and birds are placed in the seas and skies; finally, day six populates what was created on day three, and animals and man are place on the land. This six-day structure is symmetrically bracketed: On day zero primeval chaos reigns, and on day seven there is cosmic order.[31]

Genesis 2 is a simple linear narrative, with the exception of the parenthesis about the four rivers at 2:10–14. This interrupts the forward movement of the narrative and is possibly a later insertion.[32]

The two are joined by Genesis 2:4a, "These are the tôledôt (תוֹלְדוֹת in Hebrew) of the heavens and the earth when they were created." This echoes the first line of Genesis 1, "In the beginning Elohim created both the heavens and the earth," and is reversed in the next line of Genesis 2, "In the day when Yahweh Elohim made the earth and the heavens...". The significance of this, if any, is unclear, but it does reflect the preoccupation of each chapter, Genesis 1 looking down from heaven, Genesis 2 looking up from the earth.[33]

Composition

Traditionally attributed to Moses, today most scholars accept that the Pentateuch is "a composite work, the product of many hands and periods.”[34] Genesis 1 and 2 are seen as the products of two separate authors, or schools: Genesis 1 is by an author, or school of authors, called the P (for Priestly), while Genesis 2 is by a different author or or group of authors called J (for Jahwist — sometimes called non-P). There are several competing theories as to when and how these two chapters originated — some scholars believe they each come from two originally complete but separate narratives spanning the entire biblical story from creation to the death of Moses, while others believe that J is not a complete narrative but rather a series of edits of the J material, which itself was not a single document so much as a collection of material. In either case, it is generally agreed that the J account (Genesis 2) is older than P (Genesis 1), that both were written during the 1st millenium BC, and that they reached the combined form in which we know them today about 450 BC.

Exegetical points

"In the beginning..."

The first word of Genesis 1 in Hebrew, "in the beginning" (Heb. berēšît בְּרֵאשִׁית), provides the traditional Jewish title for the book. The inherent ambiguity of the Hebrew grammar in this verse gives rise to two alternative translations, the first implying that God's initial act of creation was before time was created[11] and ex nihilo (out of nothing),[6][35] the second that "the heavens and the earth" (i.e., everything) already existed in a "formless and empty" state, to which God brings form and order:[36]

- "In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void.... God said, Let there be light!" (King James Version).

- "At the beginning of the creation of heaven and earth, when the earth was (or the earth being) unformed and void.... God said, Let there be light!" (Rashi, and with variations Ibn Ezra and Bereshith Rabba).

The names of God

Two names of God are used, Elohim in the first account and Yahweh Elohim in the second account. In Jewish tradition, dating back to the earliest rabbinic literature, the different names indicate different attributes of God.[37][38] In modern times the two names, plus differences in the styles of the two chapters and a number of discrepancies between Genesis 1 and Genesis 2, were instrumental in the development of source criticism and the documentary hypothesis.

"Without form and void"

The phrase traditionally translated in English "without form and void" is tōhû wābōhû (Hebrew: תֹהוּ וָבֹהוּ). The Greek Septuagint (LXX) rendered this term as "unseen and unformed" (Greek: ἀόρατος καὶ ἀκατασκεύαστος), paralleling the Greek concept of Chaos. In the Hebrew Bible, the phrase is a dis legomenon, being used only in one other place.Jer. 4:23 There Jeremiah is telling Israel that sin and rebellion against God will lead to "darkness and chaos," or to "de-creation," "as if the earth had been ‘uncreated.’"[39]

The "rûach" of God

The Hebrew rûach (רוּחַ) has the meanings "wind, spirit, breath," but the traditional Jewish interpretation here is "wind," as "spirit" would imply a living supernatural presence co-extent with yet separate from God at creation. This, however, is the sense in which rûach was understood by the early Christian church in developing the doctrine of the Trinity, in which this passage plays a central role.[36]

The "deep"

The "deep" (Heb. תְהוֹם tehôm) is the formless body of primeval water surrounding the habitable world. These waters are later released during the great flood, when "all the fountains of the great deep burst forth" from under the earth and from the "windows" of the sky.Gen. 7:11 [20] The word itself may show literary or linguistic parallels with the Babylonian Tiawath (chaos) or the Assyrian Tamtu (deep sea).[40] Gunkel accused the conservative Christian scholar, Gordon Wenham to accept that tehôm is cognate with the Babylonian Tiamat,[20] believing its occurrence here without the definite article ha (i.e., the literal translation of the Hebrew is that "darkness lay on the face of tehôm) indicates its mythical origins.[41] However, Wenham himself writes that "there is no hint in the biblical text that the deep was a power, independent of God, which he had to fight to control. Rather is it part of his creation that does his bidding.[42]

Wenham goes on to respond to Gunkel and summarize a number of views:

Gunkel suggested that Hebrew t'hom was to be identified with Tiamat, the Babylonian goddess, slain by Marduk, whose carcass was used to create heaven and earth. He saw in Gen 1:2 an allusion to the Mesopotamian creation myths. Though Otzen (Myths in the OT, 33-34) has reaffirmed this connection, Heidel (Babylonian Genesis, 98-101) showed that a direct borrowing is impossible. Both Hebrew and Babylonian Ti'amat are independently derived from a common Semitic root. Westermann justly states that the OT usage of t'hom "does not allow us to speak of a demythologizing of a mythical idea or name as do many commentaries, When P inherited the word t'hom, it had long been used to describe a flood of waters without any mythical echo" (1:105). That is not to say that this verse shows no connection with other oriental concepts of creation. In ancient cosmogonies a reference to a primeval flood is commonplace (Westermann, 1:105-6). But the word t'hom is not an allusion to the conquest of Tiamat as in the Babylonian myth.

Further, David Tsumura has demonstrated, from standard linguistic methodology, that it is impossible to derive tehôm from Tiamat directly.[43]

Tehom cannot linguistically derive from Tiamat since the second consonant of Ti’amat, which is the laryngeal alef, disappears in Akkadian in the intervocalic position and would not be manufactured as a borrowed word. This occurs, for instance, in the Akkadian Ba'al which becomes Bel. ... Tiamat and tehom must come from a common Semitic root *thm. The same root is the base for the Babylonian tamtu and also appears as the Arabic tihamatu or tihama, a name applied to the coastline of Western Arabia, and the Ugaritic t-h-m which means "ocean" or "abyss." The root simply refers to deep waters.[44]

The "firmament"

The "firmament" (Heb. רָקִיעַ rāqîa) of heaven, created on the second day of creation and populated by luminaries on the fourth day, denotes a solid ceiling[45] which separated the earth below from the heavens and their waters above. The term is etymologically derived from the verb rāqa (רֹקַע ), used for the act of beating metal into thin plates.[20][46]

"Great sea monsters"

Heb. hatanninim hagedolim (הַתַּנִּינִם הַגְּדֹלִים) is the classification of creatures to which the chaos-monsters Leviathan and Rahab belong.[47] In Genesis 1:21, the proper noun Leviathan is missing and only the class noun great tannînim appears. The great tannînim are associated with mythological sea creatures such as Lotan (the Ugaritic counterpart of the biblical Leviathan) which were considered deities by other ancient near eastern cultures; the author of Genesis 1 asserts the sovereignty of Elohim over such entities.[46]

The number seven

Seven denoted divine completion.[48] It is embedded in the text of Genesis 1 (but not in Genesis 2) in a number of ways, besides the obvious seven-day framework: the word "God" occurs 35 times (7 × 5) and "earth" 21 times (7 × 3). The phrases "and it was so" and "God saw that it was good" occur 7 times each. The first sentence of Genesis 1:1 contains 7 Hebrew words composed of 28 Hebrew letters (7 × 4), and the second sentence contains 14 words (7 × 2), while the verses about the seventh dayGen. 2:1–3 contain 35 words (7 × 5) in total.[49]

Man in "the image of God"

(see main article Image of God)

The meaning of the "image of God" (often appearing as the Latin phrase Imago Dei) has been debated as to its precise meaning. The ancient Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria and the medieval Jewish scholar Rashi believed it referred to "a sort of conceptual archetype, model, or blueprint that God had previously made for man." His colleague Maimonides believed that it referred to man's free will.[50] Modern scholarship still debates whether the image of God was represented equally in the man and in woman, or whether Adam possessed the image more fully than Eve.[citation needed]

Typology

Biblical scholars exegete incidents in Genesis and other Hebrew Bible passages as containing prefigurations (prototypes) of cardinal New Testament concepts, including the Passion of Christ and the Eucharist.[51]

Interpretation

Questions of genre

It has been variously described as historical narrative[52][53] (i.e., a literal account); as mythic history (i.e., a symbolic representation of historical time); as ancient science (in that, for the original authors, the narrative represented the current state of knowledge about the cosmos and its origin and purpose); and as theology (as it describes the origin of the earth and humanity in terms of God).[54]

Creation myth

In academia, the Genesis creation narrative is often described as a creation or cosmogonic myth. The word myth comes from the Greek root for "story" and can describe a culture's sacred account of its origins as traced from its earliest beginnings. In this way it is being used contrary to the popular usage of the word, which often defines "myth" as being something that is "not true."[55]

Ancient Near East context

The worldview which lies behind the Genesis creation story is that of the common cosmology of the ancient Near East[45] in which Earth was conceived as a flat disk with infinite water both above and below. The dome of the sky was thought to be a solid metal bowl (tin according to the Sumerians, iron for the Egyptians) separating the surrounding water from the habitable world. The stars were embedded in the lower surface of this dome, with gates that allowed the passage of the Sun and Moon back and forth. The flat-disk Earth was seen as a single island-continent surrounded by a circular ocean, of which the known seas—what today is called the Mediterranean Sea, the Persian Gulf, and the Red Sea—were inlets. Beneath the Earth was a fresh-water sea, the source of all fresh-water rivers and wells.[45]

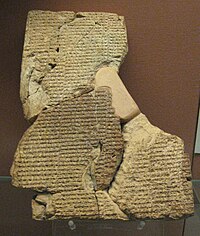

The two Genesis creation narratives—Genesis 1:1–2:3 and Genesis 2:4–2:25—are both comparable with other Near Eastern creation myths—notably Narrative I has close parallels with the Enûma Eliš[56][57] and Narrative II has parallels with the Atra-Hasis[58]

According to the Enûma Eliš the original state of the universe was a chaos formed by the mingling of two primeval waters, the female saltwater Tiamat and the male freshwater Apsu.[59] The opening six lines read:

- When skies above were not yet named

- Nor earth below pronounced by name

- Apsu, the first one, their begetter

- And maker Tiamat, who bore them all

- Had mixed their waters together,

- But had not formed pastures, nor discovered reed-beds[60]

Through the fusion of their waters six successive generations of gods were born. A war amongst the gods began with the slaying of Apsu, and ended with the god Marduk splitting Tiamat in two to form the heavens and the earth; the Euphrates and the Tigris rivers emerged from her eye-sockets. Marduk then created humanity, from clay mingled with spit and blood, to tend the earth for the gods, while Marduk himself was enthroned in Babylon in the Esagila, "the temple with its head in heaven."

Adapa (cognate with Adam) was a Babylonian mythical figure who unknowingly refused the gift of immortality. The story[61] is first attested in the Kassite period (14th century BC). Mario Liverani[62] points to multiple parallels between the story of Adapa, who obtains wisdom but who is forbidden the 'food of immortality' whilst in heaven, and the story of Adam in Eden.

Ningishzida was a Mesopotamian serpent deity associated with the underworld. He was often depicted protectively wrapped around a tree as a guardian. Thorkild Jacobsen interprets his name in Sumerian to mean "lord of the good tree"[63]

Despite apparent similarities between Genesis and the Enûma Eliš, there are also significant differences. The most notable is the absence from Genesis of the "divine combat" (the gods' battle with Tiamat) which secures Marduk's position as king of the world, but even this has an echo in the claims of Yahweh's kingship over creation in such places as Psalm 29 and Psalm 93, where he is pictured as sitting enthroned over the floods[59] and Isaiah 27:1"In that day, the Lord will punish with his sword; his fierce, great and powerful sword; Leviathan the gliding serpent, Leviathan the coiling serpent; he will slay the monster of the sea." Thus this creation account may be seen as either a borrowing or historicizing of Babylonian myth[64] or, in contrast, may be seen as a repudiation of Babylonian ideas about origins and humanity.[65]

Theology

Jewish and Christian theology both define God as unchangeable since he created time and therefore transcends time and is not affected by it.[66]

Traditional Jewish scholarship has viewed it as expressing spiritual concepts (see Nachmanides, commentary on Genesis). The Mishnah in Tractate Chagigah states that the actual meaning of the creation account, mystical in nature and hinted at in the text of Genesis, was to be taught only to advanced students one-on-one. Tractate Sanhedrin states that Genesis describes all mankind as being descended from a single individual in order to teach certain lessons. Among these are:

- Taking one life is tantamount to destroying the entire world, and saving one life is tantamount to saving the entire world.

- A person should not say to another that he comes from better stock because we all come from the same ancestor.

- To teach the greatness of God, for when human beings create a mold every thing that comes out of that mold is identical, while mankind, which comes out of a single mold, is different in that every person is unique.[67]

Among the many views of modern scholars on Genesis and creation one of the most influential is that which links it to the emergence of Hebrew monotheism from the common Mesopotamian/Levantine background of polytheistic religion and myth around the middle of the 1st millennium BC.[68] The "creation week" narrative forms a monotheistic polemic on creation-theology directed against gentile creation myths, the sequence of events building to the establishment of the biblical Sabbath (in Hebrew: שַׁבָּת, Shabbat) commandment as its climax.[69] Where the Babylonian myths saw man as nothing more than a "lackey of the gods to keep them supplied with food,"[70] Genesis starts out with God approving the world as "very good" and with mankind at the apex of created order.Gen. 1:31 Things then fall away from this initial state of goodness: Adam and Eve eat the fruit of the tree in disobedience of the divine command. Ten generations later in the time of Noah, the earth has become so corrupted that God resolves to return it to the waters of chaos sparing only one man who is righteous and from whom a new creation can begin.

Creationism

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Creationism | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| History | ||||

| Types | ||||

| Biblical cosmology | ||||

| Creation science | ||||

| Rejection of evolution by religious groups | ||||

| Religious views | ||||

|

||||

Biblical literalists are committed to interpreting the Bible by adhering closely to the explicit words given in the text.[71] The literalist interpretations of Genesis came into direct conflict with the growing body of scientific evidence in geology and biology that began to build in the late 18th and 19th centuries and continuing to the present.[72] Strict literalists view Genesis creation as a historical event that transpired exactly as written. In the words of minister and theologian John MacArthur, "Tamper with the Book of Genesis and you undermine the very foundations of Christianity.... If Genesis 1 is not accurate, then there's no way to be certain that the rest of Scripture tells the truth."[73] Both the vast age of the earth, now estimated by scientists to be about 4.5 billion years, and the common ancestry of all life ascribed by evolution, are hotly disputed in literalist creationism.

Young earth creationism

"Young earth" creationists are literalists who maintain that the Genesis creation took place between 6,000 and 10,000 years in the past, and that the seven "days" of Genesis 1 correspond to normal 24-hour days. Creation scientists, who are also primarily but not exclusively literalist young earth creationists, maintain that the science behind the age of the earth and evolution is flawed, and claim to have scientific evidence of their own that fully supports the Genesis account. Other methods of interpretation have also been adopted in reconciling the Genesis text to evidence for a much older earth.

Day-Age creationism

"Day-age" creationists believe that each "day" in Genesis's opening represents an "age" of perhaps millions or billions of years. Progressive creationists are literalists that infer each day of creation represents an eon of development rather than a 24 hour day, but place importance on both the numerical and naturalistic features in the account and claim these Genesis passages can be seen to have anticipated later scientific findings regarding the creation of the planet and solar system.[74]

Gap creationism

Gap creationism is a form of Old Earth creationism that posits that the six-day creation, as described in the Book of Genesis, involved literal 24-hour days, but that there was a gap of time between two distinct creations in the first and the second verses of Genesis. Gap creationists believe that these "days" do represent 24-hour periods, but they believe that there is a large gap of time between the first and second creation narratives in Genesis.

Evolutionary theory vs creationism

Apart from conflicts between the days specified in Genesis creation and the immense age of the earth derived in the sciences, the evolutionary theory that developed in the mid 19th century describing the common ancestry between apes and humans presented a dilemma to those who believed in the doctrine supported in Genesis that humanity was created in the "image of God". While strict literalists remained steadfast, interpreting Genesis creation as the creation of humanity in its present form, Orthodox Christians tended to differentiate between the "body" and "soul" of humanity to interpret the passage, allowing a bodily evolution while identifying the soul as the interpretation to Genesis's reference to this making in God's image. Liberal theologians were inclined to abandon a literal reading of the creation and reinterpret the Genesis passages as a symbolic, poetic or mythic telling of religious truths.[72] Prominent among them was Henry Ward Beecher who flatly rejected literalism as an impediment to their proper interpretation, writing that the scriptures "claim no such mechanical perfection as has been claimed for them."[75] For Beecher, Genesis creation was to be interpreted instead as a record of the earliest stages in a progressive evolution of religious thought.[76]

See also

- Allegorical interpretations of Genesis

- Babylonian mythology

- Biblical criticism

- Christian mythology

- Creation (disambiguation)

- Hexameron

- Jewish mythology

- Mesopotamian mythology

- Religion and mythology

- Sacred history

- Sumerian creation myth

- Sumerian literature

- Tree of life

- Timeline of the Bible

References

- ^ Yehezkiel Kaufmann The Religion of Israel, from Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile (1960) University of Chicago Press

- ^ Leeming 2004 - "Although it is canonical for both Christians and Jews, and in part for followers of Islam, different emphases are placed on the story by the three religions."

- ^ Genesis 1:1–2:3

- ^ Genesis 2:4–2:25

- ^ Genesis 2:17

- ^ a b c d See:

- Fain 2007, pp. 30–36

- Heeren 2000, pp. 107–108, 121, 135, 157

- Schaff 1995

- Clontz 2008

- Ellis 1993, p. 97

- ^ a b c Bauckham 2001

- ^ a b Goldinghay, John Old Testament Theology: Israel's Gospel v.1 Paternoster Press (19 Jan 2007) ISBN 1842274961

- ^ Gordon Wenham, Genesis: Word Biblical Commentary, Volume 1, pp. 11-12. Wenham goes on to note that while translations such as NEB and NAB appear to support creation from chaos, "by placing a period at the end of v. 2, they probably regard the main clause as "God said" in v. 3, i.e. option 2. It is the least likely interpretation in that v. 2 is a circumstantial clause giving additional background information necessary to understanding v 1 or v 3 and therefore either v 1 or v 3 must contain the main clause." After giving the history and proponents for the various creation from chaos options, Wenham sides with creation ex nihilo in the present text (page 13) because of the pointing in the current version of the Masoretic text (10th century AD) and the syntax of the LXX (3rd century B.C.E.) which both support the traditional view, showing both consistency and age for the view in the text we now have. Regardless of the theoretical view of an Ur text, any commentary based on the actual texts that exist must side with creation ex nihilo. Finally, Wenham cites Hasel's argument that the traditional "interpretation becomes the more likely since it is apparent that vv. 2-3 are not a straight borrowing of extrabiblical ideas. Mesopotamian sources formulate their descriptions negatively -- 'When the heaven had not yet been named' -- whereas v 2 is positive, 'the earth was total chaos.' In other words, it looks as though vv 2-3 were composed by the writer responsible for v 1, and not simply borrowed from a pre-biblical source. This makes it most natural to interpret the text synchronically, i.e., v 1: first creative act; v 2: consequence of v 1; v 3 first creative word. Notter (23-26) points out that the idea that a god first created matter, the primeval ocean, and then organized it, has many Egyptian parallels. Whether this, the traditional understanding of these verses, does justice to the exact wording of Genesis must now be investigated." Wenham concludes his analysis that (page 15) "Genesis 1:1 could therefore be translated 'In the beginning God created everything.'"

- ^ Word Biblical Commentary, Volume 1, pp. 9

- ^ a b c Yonge 1854

- ^ Clontz, T.E. and J. (2008). "The Comprehensive New Testament with complete textual variant mapping and references for the Dead Sea Scrolls, Philo, Josephus, Nag Hammadi Library, Pseudepigrapha, Apocrypha, Plato, Egyptian Book of the Dead, Talmud, Old Testament, Patristic Writings, Dhammapada, Tacitus, Epic of Gilgamesh. Cornerstone Publications. ISBN 978-0-977873-71-5. (p. 473 Philo[Special Laws IV (187) cf. {Genesis 1:1-31}]; p. 494 Philo[Appendices A Treatise Concerning the World (1) cf. {Genesis 1:1, Deuteronomy 10:17})

- ^ The Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers First Series, Volume 1 The Confessions and Letters of Augustine with a Sketch of his Life and Work, 1896, Philip Schaff, Augustine Confessions — Book XI.11-30, XII.7-9

- ^ Commentaries on The First Book of Moses Called Genesis, by John Calvin, Translated from the Original Latin, and Compared with the French Edition, by the Rev. John King, M.A, 1578, Volume 1, Genesis 1:1-31 see http://www.ccel.org/ccel/calvin/calcom01.vii.i.html - “In the beginning. To expound the term “beginning,” of Christ, is altogether frivolous. For Moses simply intends to assert that the world was not perfected at its very commencement, in the manner in which it is now seen, but that it was created an empty chaos of heaven and earth. His language therefore may be thus explained. When God in the beginning created the heaven and the earth, the earth was empty and waste. He moreover teaches by the word “created,” that what before did not exist was now made; for he has not used the term יצר, (yatsar,) which signifies to frame or forms but ברא, (bara,) which signifies to create. Therefore his meaning is, that the world was made out of nothing. Hence the folly of those is refuted who imagine that unformed matter existed from eternity; and who gather nothing else from the narration of Moses than that the world was furnished with new ornaments, and received a form of which it was before destitute.”

- ^ John Wesley’s notes on the whole Bible the Old Testament, Notes On The First Book Of Moses Called Genesis, by John Wesley, p.14 see http://www.ccel.org/ccel/wesley/notes.ii.ii.ii.i.html - “Observe the manner how this work was effected; God created, that is, made it out of nothing. There was not any pre-existent matter out of which the world was produced. The fish and fowl were indeed produced out of the waters, and the beasts and man out of the earth; but that earth and those waters were made out of nothing. Observe when this work was produced; In the beginning — That is, in the beginning of time. Time began with the production of those beings that are measured by time. Before the beginning of time there was none but that Infinite Being that inhabits eternity.”

- ^ Matthew Henry’s Commentary on the Whole Bible, Unabridged, Genesis to Deuteronomy, by Matthew Henry see http://www.ccel.org/ccel/henry/mhc1.Gen.ii.html - “The manner in which this work was effected: God created it, that is, made it out of nothing. There was not any pre-existent matter out of which the world was produced. The fish and fowl were indeed produced out of the waters and the beasts and man out of the earth; but that earth and those waters were made out of nothing. By the ordinary power of nature, it is impossible that any thing should be made out of nothing; no artificer can work, unless he has something to work on.

- ^ a b Alter, Robert (1997). Genesis: Translation and Commentary. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 7. ISBN 9780393316704.

- ^ Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth, disc 1 of 6.

- ^ Frank Moore Cross, "The Priestly Work," in Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic, 1973. The other nine are for:

- 2 Adam [1], Genesis 5:1

- 3 Noah,Genesis 6:9

- 4 Noah's sons Genesis 10L1,

- 5 Shem,Gen. 11:10

- 6 Terah,Gen. 11:27

- 7 Yishmael,Gen. 25:12

- 8 Isaac,Gen. 25:19

- 9 Esau,Gen. 36:1 and

- 10 Jacob.Gen. 37:2

- ^ a b c d Gordon J. Wenham. Genesis 1–15 (Word Biblical Commentary). Word Books, Texas, 1987.

- ^ The argument is based on several grounds, notably the fact that Genesis 1 uses the phrase "heavens and earth" to introduce and close the creation, while the account in Chapter 2 is introduced by the phrase "earth and heavens." Advocates of the other view argue that Genesis 2:4 is designed as a chiasm (Wenham, 49)

- ^ Rendtorff, Rolf (2009). Problem of the Process of Transmission in the Pentateuch. Sheffield Academic Press. p. 41. ISBN 0567187926.

- ^ a b Hyers 1984, p. 107

- ^ The lack of punctuation in the Hebrew creates ambiguity over where sentence-endings should be placed in this passage. This is reflected in differing modern translations, some of which attach this clause to Genesis 2:4a and place a full stop at the end of 4b, while others place the full stop after 4a and make 4b the beginning of a new sentence, while yet others combine all verses from 4a onwards into a single sentence culminating in Genesis 2:7.

- ^ in some translations, a stream

- ^ `ezer: Most often used to refer to God, such as "The Lord is our Help (`ezer)"Ps. 115:9 and many other Old Testament verses. (Strong's H5828)

- ^ footnote to Gen. 2:18 in NASB

- ^ Kvam, Kristen E., Linda S. Schearing, Valarie H. Ziegler, eds. Eve and Adam: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim readings on Genesis and gender. Indiana University Press, 1999. ISBN 0253212715.

- ^ Hebrew tsela`, meaning side, chamber, rib, or beam (Strong's H6763). Some scholars have questioned the traditional "rib" on the grounds that it denigrates the equality of the sexes, suggesting it should read "side": see Reisenberger, Azila Talit. "The creation of Adam...." in Judaism: A Quarterly Journal of Jewish Life and Thought, 9/22/1993 (accessed 09–12–2007).

- ^ entry creation, page 193, in Harper's Bible Dictionary, general editor Paul J. Achtemeier, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1985, ISBN 0-06-069862-4

- ^ Bandstra, Barry L. (1999), "Priestly Creation Story", Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible, Wadsworth Publishing Company.

- ^ David Carr, “The Politics of Textual Subversion: A Diachronic Perspective on the Garden of Eden Story”, Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 112, No. 4 (Winter, 1993), pp. 577–595.

- ^ Richard Elliott Friedman, "The Bible With Sources Revealed", (Harper San Francisco, 2003), fn 3, p. 35

- ^ Speiser, E. A. (1964). Genesis. The Anchor Bible. Doubleday. p. XXI. ISBN 0-385-00854-6.

- ^ Wenham, Gordon. Word Biblical Commentary Vol. 1 Genesis 1–15. Word, 1987. ISBN 0849902002

- ^ a b Harry Orlinsky, Notes on Genesis, NJPS translation of the Torah

- ^ "Hashem/Elokim: Mixing Mercy with Justice" in The Aryeh Kaplan Reader [2]

- ^ The seventy faces of Torah: the Jewish way of reading the Sacred Scriptures, by Stephen M. Wylen [3]

- ^ H.B. Huey, vol. 16, Jeremiah, Lamentations, "The New American Commentary" (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2001, c1993), p. 85; Holladay, Jeremiah 1, p. 164; Thompson writes, "it's as if the earth had been ‘uncreated.’", Thompson, Jeremiah, NICOT, p. 230;

- ^ Lewis Spence, Myths and Legends of Babylonia and Assyria (Easton Press edition), page 72

- ^ Noted by Hermann Gunkel—see Ernest Nicholson, "The Pentateuch in the Twentieth Century", 2002, p.34.)

- ^ Gordon Wenham, Genesis: The Word Biblical Commentary, Volume 1, page 16

- ^ Tsumura (2005)

- ^ Roberto Ouro, "The Earth of Genesis 1:2: abiotic or chaotic?", Andrews University Seminary Studies '37' (1999): 39–53.

- ^ a b c For a description of Near Eastern and other ancient cosmologies and their connections with the biblical view of the universe, see Paul H. Seeley, "The Firmament and the Water Above: The Meaning of Raqia in Genesis 1:6–8", Westminster Theological Journal 53 (1991), and "The Geographical Meaning of 'Earth' and 'Seas' in Genesis 1:10", Westminster Theological Journal 59 (1997).

- ^ a b Victor P. Hamilton. The Book of Genesis (New International Commentary on the Old Testament). William B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, 1990.

- ^ Vocabulary of Biblical Hebrew, Texas A&M University.

- ^ Meir Bar-Ilan, The Numerology of Genesis (Association for Jewish Astrology and Numerology, 2003)

- ^ Gordon Wenham, Genesis 1–15 (Commentary, Word Books, 1987. p. 6

- ^ Footnotes to Genesis translation at bible.ort.org

- ^ Janzen, David. The social meanings of sacrifice in the Hebrew Bible: a study of four writings. Walter de Gruyter Publisher, 2004. ISBN 978-3110181586

- ^ Feinberg, John S. (2006). "The Doctrine of Creation—Literary Genre of Genesis 1 and 2". No One Like Him: The Doctrine of God. Foundations of Evangelical Theology. Vol. 2. Good News Publishers. p. 577. ISBN 1581348118.

- ^ Boyd, Steven W. (2008). "The Genre of Genesis 1:1-2:3:What Means This Text?". In Terry Mortenson, Thane H Ury (ed.). Coming to Grips with Genesis: Biblical Authority and the Age of the Earth. New Leaf Publishing Group. pp. 174 ff. ISBN 0890515484.

- ^ Sparks, Kenton. God's Word in Human Words: An Evangelical Appropriation of Critical Biblical Scholarship. Baker Academic, 2008. ISBN 0801027012 (see Chapters 6 & 7 on Biblical Genres)

- ^ Wright, N.T. Meaning and Myth. The BioLogos Foundation » Science & the Sacred. Web: 1 Mar 2020. Meaning and Myth.

- ^ Heidel, Alexander. Babylonian Genesis Chicago University Press; 2nd edition edition (1 Sep 1963) ISBN 0226323994 (See especially Ch3 on Old Testament Parallels)

- ^ Smith, Mark S. The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts Oxford University Press USA (30 Aug 2001) ISBN 019513480X (See especially Ch 9.1)

- ^ Dalley, Stephanie Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh, and others Oxford World Classics, Oxford University Press (2000) ISBN 0192835890 (see esp. p.4 Atrahasis Introduction on 'Creation of Man')

- ^ a b Bandstra, Barry L. (1999), "Enûma Eliš", Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible, Wadsworth Publishing Company.

- ^ Dalley, Stephanie. Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh, and others. Oxford World Classics, Oxford University Press (2000) ISBN 0192835890 (p233 The Epic of Creation. Tablet 1.) [4]

- ^ Adapa: Babylonian mythical figure

- ^ Liverani, Mario. Myth and Politics in Ancient Near Eastern Historiography. Cornell University Press (August 30, 2007) (Ch1 Adapa, guest of the Gods pp.21-23) [5]

- ^ Jacobsen, Thorkild The Treasures of Darkness: History of Mesopotamian Religion Yale University Press; New edition edition (1 July 1978) ISBN 0300022913 (page 7)

- ^ Heidel, Alexander Babylonian Genesis Chicago University Press; 2nd edition edition (1 Sep 1963) ISBN 0226323994; Smith, Mark S. The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel William B Eerdmans Publishing Co; 2nd edition (18 Oct 2002) ISBN 080283972X; Smith, Mark S. The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts Oxford University Press USA; New Ed edition (27 Nov 2003) ISBN 0195167686; Frank Moore Cross 'Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel' Harvard University Press; New edition edition (29 Aug 1997) ISBN 0674091760]

- ^ K. A. Mathews, vol. 1A, Genesis 1-11:26, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2001), p. 89.

- ^ Clontz 2008

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Sanhedrin 37a.

- ^ For a discussion of the roots of biblical monotheism in Canaanite polytheism, see Mark S. Smith, "The Origins of Biblical Monotheism"; See also the review of David Penchansky, "Twilight of the Gods: Polytheism in the Hebrew Bible", which describes some of the nuances underlying the subject. See the Bibliography section at the foot of this article for further reading on this subject.

- ^ Meredith G. Kline, "Because It Had Not Rained", (Westminster Theological Journal, 20 (2), May 1958), pp. 146–57; Meredith G. Kline, "Space and Time in the Genesis Cosmogony", Perspectives on Science & Christian Faith (48), 1996), pp. 2–15; Henri Blocher, Henri Blocher. In the Beginning: The Opening Chapters of Genesis. InterVarsity Press, 1984.; and with antecedents in St. Augustine of Hippo Davis A. Young (1988). "The Contemporary Relevance of Augustine's View of Creation". Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith. 40 (1): 42–45.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|Format=|Format=ignored (|format=suggested) (help) - ^ T. Jacobson, "The Eridu Genesis", JBL 100, 1981, pp.529, quoted in Gordon Wenham, "Exploring the Old Testament: The Pentateuch", 2003, p.17. See also Gordon J. Wenham. Genesis 1–15 (Word Biblical Commentary). Word Books, Texas, 1987.

- ^ Lindbeck 2001, p. 295

- ^ a b Stenhouse 2000, p. 76

- ^ Scott 2005, pp. 227–8

- ^ Hyers 1984, p. 80

- ^ Ryan 1990, p. 70

- ^ Beecher 1885, p. 65

Bibliography

- Anderson, Bernhard W. (1997). Creation Ver Bernhard W. Understanding the Old Testament. ISBN 0-13-948399-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Anderson, Bernhard W. (1985). Creation in the Old Testament. ISBN 0-8006-1768-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bauckham, Richard (2001). Word Biblical Commentary: Jude, 2 Peter. Thomas Nelson Publishers. p. 297. ISBN 0849902495.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) "According to the creation account in Gen 1, and in accordance with general Near Eastern myth, the world—sky and earth—merged out of a primeval ocean (Gen 1:2, 6–7, 9; cf. Ps 33:7; 136:6; Prov 8:27–29; Sir 39:17; Herm. Vis. 1:3:4). The world exists because the waters of chaos, which are now above the firmament, beneath the earth and surrounding the earth, are held back and can no longer engulf the world. The phrase ἐξ ὕδατος ('out of water') expresses this mythological concept of the world's emergence out of the watery chaos, rather than the more 'scientific' notion, taught by Thales of Miletus, that water is the basic element out of which everything else is made (cf. Clem. Hom. 11:24:1)." - Beecher, Henry Ward (1885). Evolution and religion. Pilgrim Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Benware, P.N. (1993). Survey of the Old Testament. Moody Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Blocher, Henri AG (1984). In the Beginning: the opening chapters of Genesis. InterVarsity Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bloom, Harold and Rosenberg (1990). David The Book of J. New York, USA: Random House.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clontz, T.E. and J. (2008). "The Comprehensive New Testament with complete textual variant mapping and references for the Dead Sea Scrolls, Philo, Josephus, Nag Hammadi Library, Pseudepigrapha, Apocrypha, Plato, Egyptian Book of the Dead, Talmud, Old Testament, Patristic Writings, Dhammapada, Tacitus, Epic of Gilgamesh. Cornerstone Publications. pp. 476, 497. ISBN 978-0-977873-71-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Copan, Paul (1996). "Is Creatio Ex Nihilo A Post-Biblical Invention?: An Examination Of Gerhard May's Proposal". 17. Trinity Journal: 77–93.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Davis, John (1975). Paradise to Prison—Studies in Genesis. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House. p. 23.

- Douglas, J.D.; et al. (1990). Old Testament Volume: New Commentary on the Whole Bible. Wheaton, IL: Tyndale,.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last2=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Ellis, George F. R. (1993). Before the Beginning: Cosmology Explained. London and New York: Boyars/Bowerdean. p. 97.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fain, Benjamin (2007). Creation Ex Nihilo: Thoughts on Science, Divine Providence, Free Will, and Faith in the Perspective of My Own Experiences. pp. 30–36.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Friedman, Richard E. (2003). Commentary on the Torah. HarperOne. ISBN 0060625619.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Friedman, Richard E. (1987). Who Wrote The Bible?. NY, USA: Harper and Row. ISBN 0060630353.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gunkel, Hermann (1894). Schöpfung und Chaos in Urzeit und Endzeit. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hamilton, Victor P (1990). The Book of Genesis. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Heeren, Fred (2000). Show Me God: What the Message from Space Is Telling Us About God. Day Star Publications. pp. 107–108, 121, 135, 157.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Heidel, Alexander (1963). Babylonian Genesis (2nd ed.). Chicago University Press. ISBN 0226323994.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Heidel, Alexander (1963). Gilgamesh Epic and Old Testament Parallels (2nd Revised ed.). Chicago University Press. ISBN 0226323986.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Hyers, Conrad (1984). The Meaning of Creation: Genesis and Modern Science. Atlanta: John Knox Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lindbeck, George (2001). Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. Baker Academy. p. 295.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|chaper=ignored (help) - King, Leonard (2007). Enuma Elish: The Seven Tablets of Creation; The Babylonian and Assyrian Legends Concerning the Creation of the World and of Mankind. Vol. 1 and 2. Cosimo Inc. ISBN 1602063192.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Leeming, David A. (2004). "Biblical creation". The Oxford companion to world mythology (online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - May, Gerhard (1994). Creatio ex Nihilo: The Doctrine of "Creation out of Nothing" in Early Christian Thought (English version ed.). Edinburgh: T & T Clark.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nicholson, Ernest (2003). The Pentateuch in the Twentieth Century: The Legacy of Julius Wellhausen. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Penchansky, David (2005). Twilight of the Gods: Polytheism in the Hebrew Bible (Interpretation Bible Studies). U.S.: Westminster/John Knox Press. ISBN 0664228852.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Reis, Pamela Tamarkin (2001). "Genesis as "Rashomon": The creation as told by God and man". 17 (3). Bible Review.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rouvière, Jean-Marc (2006). Brèves méditations sur la création du monde (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schaff, Philip (1995). "The Confessions and Letters of Augustine with a Sketch of his Life and Work". The Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers. First. Vol. 1. Hendrickson Publishers. ISBN 1565630955.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Scott, Eugenie C. (2005). "John MacArthur". Evolution vs Creationism: An Introduction. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520246508.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, George (2004). The Chaldean account of Genesis: Containing the description of the creation, the fall of man, the deluge, the tower of Babel, the times of the ... of the gods; from the cuneiform inscriptions. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1402150997.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Smith, Mark S. (2002). The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel (2nd ed.). William B Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 080283972X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Smith, Mark S. (2003). The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts (New Ed ed.). Oxford University Press USA. ISBN 0195167686.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Spurrell, G.J. (1896). Notes on the Text of the Book of Genesis. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stenhouse, John (2000). "Genesis and Science". In Gary B. Ferngren (ed.). The History of Science and Religion in the Western Tradition: An Encyclopedia. New York, London: Garland Publishing, Inc. p. 76. ISBN 0-8153-1656-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ryan, Halford R. (1990). Henry Ward Beecher : Peripatetic Preacher. New York: Greenwood Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help). - Tigay, Jeffrey (1986). Empirical Models for Biblical Criticism. Philadelphia, PA, USA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tsumura, David Toshio (2005). "The Earth in Genesis 1; The Waters in Genesis 1; The Earth in Genesis 2; The Waters in Genesis 2". Creation and destruction: a reappraisal of the Chaoskampf theory in the Old Testament (Revised and expanded ed.). Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061061.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walton, John H. (2006). Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. Baker Academic. ISBN 0801027500.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Wenham, Gordon (1987). Genesis 1-15. Vol. 1 and 2. Word Books.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Yonge, Charles Duke (1854). "Appendices A Treatise Concerning the World (1), On the Creation (16-19, 26-30), Special Laws IV (187), On the Unchangeableness of God (23-32)". The Works of Philo Judaeus: the contemporary of Josephus. London: H. G. Bohn.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

Sources for the biblical text

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (Hebrew-English text, translated according to the JPS 1917 Edition)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 (Hebrew-English text, with Rashi's commentary. The translation is the authoritative Judaica Press version, edited by the esteemed translator and scholar, Rabbi A.J. Rosenberg.)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (King James Version)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (Revised Standard Version)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (New Living Translation)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (New American Standard Bible)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (New International Version (UK))

- "Enuma Elish", at Encyclopedia of the Orient Summary of Enuma Elish with links to full text.

- ETCSL—Text and translation of the Eridu Genesis (alternate site) (The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford)

- "Epic of Gilgamesh" (summary)

- British Museum: Cuneiform tablet from Sippar with the story of Atra-Hasis

Other resources

- Alexander Heidel, "Babylonian Genesis" A classic text, at Wikibooks

- Comparing the myths of Adapa and Adam, prototypes of priest and humankind (summary of Liverani's views)

- Hexaemeron—Catholic Encyclopedia article

- Jacob Boehme's vision on Genesis His book Mysterium Magnum.

- Mark S. Smith, "The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts", Bible and Interpretation.

- Paul H. Seely, "The Firmament and the Water Above", The Westminster Theological Journal 53 (1991) ANE cosmography

- Paul H. Seely, "The Geographical Meaning of 'Éarth' and 'Seas' in Genesis 1:10", Westminster Theological Journal 59 (1997) ANE cosmography.

- Philo—On the Creation

- Philo—Questions and Answers on Genesis

- Religious practices in late 7th century Israel

- Review of Benjamin R. Foster, Before the Muses: An Anthology of Akkadian Literature (2005) Includes comments on parallels between ancient Mesopotamian literature and biblical texts.

- Review of James P. Allen, The Egyptian Pyramid Texts (2005)

- Review of John Day, Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan (2000).

- Six Days of Creation: Islamic View

- The Multiple Authorship of the Books Attributed to Moses