History of the Georgia Institute of Technology

The history of the Georgia Institute of Technology began shortly after the American Civil War and extends nearly 150 years. In that time, the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech) has undergone significant change, expanding from a small trade school to the largest technological institution in the Southeastern United States. It was established after the Civil War in order to improve the industrial competitiveness of the Southern United States, with the first and only degree being in Mechanical Engineering.[1] Other engineering degrees were added soon thereafter, including Textile, Electrical, and Chemical Engineering.

The Georgia Tech Research Institute has its roots in the school's early history; it was created in 1934 to assist in the state's industrial development using the school's reputation and resources.[2] The institute has spawned both Georgia State University and the Southern Polytechnic State University, with the former enrolling Georgia Tech's first female students in the 1920s. The school would not officially allow women to enroll until 1952, and to enroll in any program until 1968. Georgia Tech was also one of the few southern educational institutions to integrate peacefully, doing so in 1961.

In 1990, the school opened its first international campus, Georgia Tech Lorraine, and in 1996, it was the Olympic Village for the 1996 Summer Olympics. The recent history of the institute has been focused on rapid expansion, including apartments and an open-air competition pool built when it served as the Olympic Village for the 1996 Summer Olympics and the construction of several large academic and research buildings. The school has also established several new campuses, most notably Georgia Tech Savannah in Savannah, Georgia and its first international campus, Georgia Tech Lorraine in Metz, France. The school has also taken care to maintain its "Historic District", with several projects dedicated to the preservation or improvement of Tech Tower, the school's first and oldest building, and its primary administrative center. The National Register of Historic Places has listed the Georgia Tech Historic District since 1978.[3][4] Academically, the school has gradually improved their rankings and have given significant attention to modernizing the campus, increasing historically low retention rates, and establishing degree options that emphasize research or an international perspective.

Establishment

A historical marker on the large hill in Central Campus notes that the site occupied by the school's first buildings once held fortifications built to protect Atlanta during the Atlanta Campaign of the American Civil War. The surrender of the city had taken place on the southwestern boundary of the modern Georgia Tech campus in 1864.[5]

The idea of Georgia Institute of Technology was introduced in 1865 during the Reconstruction period. Two former Confederate officers, Major John Fletcher Hanson and Nathaniel Edwin Harris, who had become prominent citizens in the town of Macon, Georgia after the war, strongly believed that the South needed to improve its technology to compete with the industrial revolution that was occurring throughout the North.[6][7] Many Southerners at this time agreed with this idea, known as the "New South Creed."[2] Its strongest proponent was Henry W. Grady, editor of the Atlanta Constitution during the 1880s.[2] A technology school was needed because the American South of that era was mainly comprised of agricultural workers and few technical developments were occurring.[6][7]

With authorization from the Georgia state legislature, Harris and a committee of prominent Georgians visited technology schools in the Northeast in 1882. Using examples from the Worcester County Free Institute of Industrial Science (now Worcester Polytechnic Institute) and Boston Tech (now Massachusetts Institute of Technology), the Atlanta technology school began development on the Worcester Free Institute model, which stressed a combination of "theory and practice." The latter component included student employment and production of consumer items to generate revenue for the school.[8]

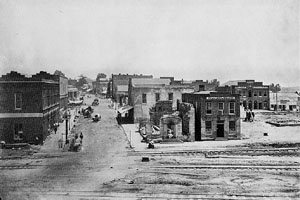

On October 13, 1885, Georgia Governor Henry D. McDaniel signed the bill to create and fund the new school.[9] A committee was then established to determine the location of the new school.[9] Patrick Hues Mell, the president of the University of Georgia at that time, believed that it should be located at Athens with the University's main campus, like the Agricultural and Mechanical School.[10] Despite Mell's arguments, the new school was to be located in Atlanta, Georgia. A site was found for the school in 1887 when Atlanta pioneer Richard Peters donated four acres of his extensive land holdings to the state; this land was bounded on the south by North Avenue, and on the west by Cherry Street.[9] He then sold five adjoining acres of land to the state for $10,000, approximately equivalent to $182,717.44 in 2006.[9][11] This land was what were then Atlanta's northern city limits.[10]

Early years

- Includes the administration of Isaac S. Hopkins (1888–1896)

The time and attention of students will be duly proportioned between scholastic and mechanical pursuits, and special prominence will be given to the element of practice in every department.[12]

— Georgia School of Technology Prospectus, 1888

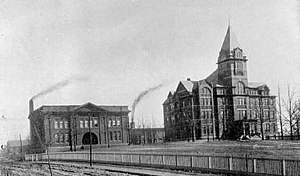

The Georgia School of Technology opened its doors in the fall of 1888 with only two buildings, and under the leadership of professor and pastor Isaac S. Hopkins.[6] One building (now Tech Tower, the main administrative complex) had classrooms to teach students; the other featured a workshop with a foundry, forge, boiler room and engine room. It was designed specifically as a "contract shop" where students would work to produce goods to sell, creating revenue for the school while the students learned vocational skills in a "hands-on" manner.[2][7] Such a method was seen as appropriate given the Southern United States' need for industrial development.[2] The two buildings were equal in size to show the importance of teaching both the mind and the hands; at the time, however, there was some disagreement as to whether the machine shop should have been used to turn a profit.[6][8] The contract shop system ended in 1896 due to its lack of profitability, after which point the items produced were used to furnish the offices and dorms on the campus.[7]

The first class of students at the Georgia School of Technology was small and homogeneous, and educational options were limited. The initial enrollment consisted of around 100 men, with sources reporting numbers from 84 to 129.[1][13][14] All but one or two of the students were from Georgia.[13] The faculty, led by the School's president, Isaac S. Hopkins, comprised 11 professors and instructors. Tuition was free for Georgia residents and $150 for out-of-state students.[12] The only degree offered was a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering, and no elective courses were available. All students were required to follow exactly the same program, which was so rigorous that nearly two thirds of the first class failed to complete it.[1]

Tech's first student publication was the Technologian, which ran for a short time in 1891.[13] The next student publication was established in 1894 and was called The Georgia Tech.[15] The Georgia Tech published a "Commencement Issue" that reviewed sporting events and gave information about each class.[15] The Technique was founded in 1911; its first issue was published on November 17, 1911 by editors Albert Blohm and E.A. Turner, and the content revolved around the upcoming rivalry football game against the University of Georgia.[16][17][18] The Technique has been published weekly ever since, with the exception of a brief period that the paper was published twice weekly.[19] The Georgia Tech and the Technique operated separately for several years following the Technique's establishment, though the two publications eventually merged in 1916.[18]

Trade school

- Includes the administration of Lyman Hall (1896–1905)

In 1888, Captain Lyman Hall was appointed Georgia Tech's first mathematics professor, a position he held until his appointment as the school's second president in 1896. He had a solid background in engineering due to his time at West Point and often incorporated surveying and other engineering applications into his coursework. He had an energetic personality and quickly assumed a leadership position among the faculty. As president, Hall was noted for his aggressive fundraising and improvements to the school, including his special project, the A. French Textile School.[20] In February 1899, Georgia Tech opened the first textile engineering school in the Southern United States,[21] with $10,000 from the Georgia General Assembly, $20,000 of donated machinery, and $13,500 from supporters.[22] It named the A. French Textile School, after its chief donor and supporter, Aaron French. The textile engineering program would later move to the Harrison Hightower Textile Engineering Building in 1949.[21][23]

Lyman Hall's other goals included enlarging Tech and attracting more students, so he introduced a number of new degrees, including civil and electrical engineering.[24] Hall also became infamous as a disciplinarian, even suspending the entire senior class of 1901 for returning from Christmas vacation a day late.[25] His death on August 16, 1905, while still in office during a vacation at a New York health resort, has been attributed to stress from his strenuous fund raising activities (this time, for a new Chemistry building).[13] Later that year, the school's trustees named the new chemistry building the "Lyman Hall Laboratory of Chemistry" in his honor.[13][26][27]

On October 20, 1905, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt visited the Georgia Tech campus. On the steps of Tech Tower, Roosevelt presented a speech about the importance of technological education:[28]

America can be the first nation only by the kind of training and effort which is developed and is symbolized in institutions of this kind... Every triumph of engineering skill credited to an American is credited to America. It is incumbent upon you to do well, not only for your individual sakes, but for the sake of that collective American citizenship which dominates the American nation.

He then shook hands with every student.[29] Tech was later visited by president-elect William H. Taft on January 16, 1909 and president Franklin D. Roosevelt on November 29, 1935.[28]

Technological university

- Includes the administrations of Kenneth G. Matheson (1906–1922) and Marion L. Brittain (1922–1944)

Georgia Tech's Evening School of Commerce began holding classes in 1912.[30] The school admitted its first female student in 1917, although the state legislature did not officially authorize attendance by women until 1920.[30][31] Anna Teitelbaum Wise became the first female graduate in 1919 and went on to become Georgia Tech's first female faculty member the following year.[30][31][32]

In its first decades of existence, the school slowly grew from a trade school into a university. However, there was little state initiative to see the school grow drastically until 1919.[2] That year, coinciding with federal debate about the establishment of Engineering Experiment Stations in a move similar to the Hatch Act of 1887's establishment of Agricultural experiment stations, the Georgia General Assembly passed an act entitled "Establishing State Engineering Experiment Station at the Georgia School of Technology."[2][30] The EES was established with the goal of the "encouragement of industries and commerce" within the state. Unfortunately, the federal effort failed and the state did not finance the organization, so the new organization existed only on paper.[2][30]

In 1929, some Georgia Tech faculty members belonging to Sigma Xi started a Research Club at Tech that met once a month.[13] One of the monthly subjects, proposed by W. Harry Vaughan, was a collection of issues related to Tech, such as library development, and the development of a state engineering station. This group investigated the forty existing engineering experiments at universities around the country, and the report was compiled by Harold Bunger, Montgomery Knight, and Vaughan in December 1929.[13]

The Georgia Board of Regents transferred control of the Evening School of Commerce to the University of Georgia in 1931, moving the civil and electrical engineering courses at UGA to Tech.[31][30] Tech replaced the commerce school with a degree in Industrial Management that evolved into Tech's College of Management. The commerce school eventually split from UGA and became Georgia State University.[30][33]

In 1933, S. V. Sanford, president of the University of Georgia, proposed that a "technical research activity" be established at Tech. President Marion L. Brittain and Dean William Vernon Skiles asked for and examined the Research Club's 1929 report, and moved to create such an organization. Vaughan was selected as its acting director in April 1934, and $5,000 in funds were allocated directly from the Georgia Board of Regents.[2][13] These funds went to the previously-established EES; its initial areas of focus were textiles, ceramics, and helicopter engineering.[34] EES later became the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI).[34]

The EES's early work was conducted in the basement of the Shop Building, and Vaughan's office was in the Aeronautical Engineering Building.[13] By 1938, the Engineering Experiment Station was producing useful technology, and the station needed a method to conduct contract work outside of the state budget.[2] Consequently, the Industrial Development Council (IDC) was formed. It was created by the Chancellor of the University System and the president of Georgia Power Company, and the Engineering Experiment Station's director was a member of the council.[2] The IDC later became the Georgia Tech Research Corporation, which currently serves as the sole contract organization for all Georgia Tech faculty and departments.[2]

Until the mid 1940s, the school required students to be able to create a simple electric motor regardless of their major.[35] During the second world war, as an engineering school with strong military ties through its ROTC program, Georgia Tech was swiftly enlisted for the war effort. In early 1942 the traditional nine-month semester system was replaced by a year-round trimester year, enabling students to complete their degrees a year earlier. Under the plan, students were allowed to complete their engineering degrees while on active duty.[36] During World War II, Georgia Tech was one of only five U.S. colleges feeding the U.S. Navy's officer program.

Integration

- Includes the administrations of Blake R. Van Leer (1944–1956), Edwin D. Harrison (1957–1969), and Arthur G. Hansen (1969–1971)

Founded as the "Georgia School of Technology," the school assumed its present name in 1948 to reflect a growing focus on advanced technological and scientific research.[37] Unlike similarly-named universities (such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the California Institute of Technology), the Georgia Institute of Technology is a public institution.

The Southern Technical Institute (STI) was established in 1948 in barracks on the campus of the Naval Air Station Atlanta (now DeKalb Peachtree Airport) in Chamblee, northeast of Atlanta.[38] At that time, all colleges in Georgia were considered extensions of the state's four research universities, and the Southern Technical Institute belonged to Georgia Tech. STI was begun as an engineering technology school, to help military personnel returning from World War II gain a hands-on experience in technical fields. Around 1958, the school moved to Marietta, to land donated by Dobbins Air Force Base.[38] The Southern Technical Institute was split from Georgia Tech in 1981. The split coincided with the separation of most other regional schools from the University of Georgia, Georgia State University, and Georgia Southern University.

The only women that had attended Georgia Tech did so through the School of Commerce. After it was removed in 1931, women were not able to enroll at the school until 1952.[32][39] In 1952, women could only enroll in programs not offered at other universities in Georgia. In 1968, the Board of Regents voted to allow women to enroll in all programs at Tech.[39][30] The first women's dorm, Fulmer Hall, opened in 1969.[30] Women constituted 28.6% of the undergraduates and 25.8% of the graduate students enrolled in Fall 2006.[40]

Tech's football team was not allowed to play against the integrated University of Pittsburgh team in the 1956 Sugar Bowl by Georgia Governor Marvin Griffin, even though it would not be the first time that they would play against a desegregated opponent.[41][42] Enraged, Tech students marched on the Governor's Mansion on December 5, 1955.[41][42]

At the State Capitol, the boys pulled fire hoses from their racks, adorned the sculpt head of Civil War Hero John Gordon with an ashcan. A dozen effigies of Governor Marvin Griffin were hanged and burned during the students' march, which culminated in a 2 a.m. riot in front of the governor's mansion.[42]

Although initially opposed to the desegregated game, Dean George C. Griffin convinced the governor to change his mind and dispersed the march.[41][42]

In 1959, a meeting of 2,741 students voted by an overwhelming majority to endorse integration of qualified applicants, regardless of race.[41] Three years after the meeting, and one year after the University of Georgia's violent integration, Georgia Tech became the first university in the Deep South to desegregate without a court order.[41][43] There was little reaction to this by Tech students; according to former mayor William Hartsfield, Tech students were "too busy to hate."[41] However, Lester Maddox chose to close his restaurant (located near the modern-day Burger Bowl) rather than desegregate after losing a year-long legal battle in which he challenged the constitutionality of the public accommodations section (Title II) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[44] Tech's first black professor, William Peace, joined the faculty in 1968.[41]

Reorganization and expansion

- Includes the administrations of Joseph M. Pettit (1972–1986) and John Patrick Crecine (1987–1994)

The Institute celebrated its centennial in 1985. Among other observances, a time capsule was placed in the Student Center, and a team of historians wrote a comprehensive guide to Georgia Tech's history, Engineering the New South: Georgia Tech 1885-1985 (ISBN 0-8203-0784-X). A companion course, "History 4876," was taught that year by two of the book's six authors. The course was offered again in 1999 as a swan song to the quarter semester system.[13][45]

Institute President John Patrick Crecine proposed a controversial restructuring of the university in 1988. The Institute at that point had three colleges: the College of Engineering, the College of Management, and the catch-all COSALS, the College of Sciences and Liberal arts. Crecine reorganized the latter two into the College of Computing, the College of Sciences, and the Ivan Allen College of Management, Policy, and International Affairs.[46][47] Crecine announced the changes without asking for input, and consequently many faculty members disliked him for his top-down management style.[46] The administration sent out ballots in 1989, and the proposed changes passed, with very slim margins.[46] The restructuring took effect in January 1990. While Crecine was seen in a poor light at the time, the changes he made are considered visionary.[46]

There was controversy in every step. Management fought this, because they were the big losers... Crecine was under fire.[46]

In October 1990, Tech's first overseas campus, Georgia Tech Lorraine (GTL), opened.[30][48] It is a non-profit corporation operating under French law. GTL is primarily focused on graduate education, sponsored research, and an undergraduate summer program. In 1997, GTL was sued under Toubon Law because all course descriptions on its internet site were in English; these course descriptions constituted an advertisement for this private college and thus fell under the Toubon Law.[49] The case was dismissed on a technicality.[50]

John Patrick Crecine was instrumental in securing the 1996 Summer Olympics for Atlanta. A dramatic amount of construction occurred, creating most of what is now considered "West Campus" in order for Tech to serve as the Olympic Village.[51] The Undergraduate Living Center, Fourth Street Apartments, Sixth Street Apartments, Eighth Street Apartments, Hemphill Apartments, and Center Street Apartments housed athletes and journalists. The Georgia Tech Aquatic Center was built for swimming events, and the Alexander Memorial Coliseum was renovated.[30][51]

Modern history

- Includes the administration of G. Wayne Clough (1994–present)

In 1994, G. Wayne Clough became the first Tech alumnus to serve as the President of the Institute, and was in office during the 1996 Summer Olympics. In 1998, he separated the Ivan Allen College of Management, Policy, and International Affairs into the Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts and returned the College of Management to "College" status.[46][52][53][54] During his tenure, research expenditures have increased from $212 million to $425 million, computers are become required for all students, enrollment has increased from 13,000 to 17,000, Tech received the Hesburgh Award,[55] and Tech's U.S. News & World Report rankings steadily improved.[56]

Clough's tenure has been especially focused on a dramatic expansion and modernization of the institute. Coinciding with the rise of personal computers, computer ownership became mandatory for all students.[57] In 1998, Georgia Tech was the first university in the Southeastern United States to provide its fraternity and sorority houses with internet access.[58] A campus Local Area Wireless/Walkup Network (LAWN) was established in 1999, and now covers most of campus.[59] Clough's administration has also focused on improved Undergraduate Research opportunities and the creation of an "International Plan" that requires students to spend two terms abroad and take internationally-focused courses.[60][61][62]

A "Master Plan" for the physical growth and development of the institute has existed since 1912,[63] and has seen significant revisions in 1952, 1965, 1991, 1997, and 2002.[63][64][65][66][67] The latter two of those major revisions have been under Clough's guidance. Since Clough took office, over $900 million has been spent on expanding or improving the campus. These projects include the completion and subsequent renovations of several west campus dorms,[65] the Manufacturing Related Disciplines Complex,[68] 10th and Home, Tech Square, The Biomedical Complex,[69] the Student Center renovation, the expanded 5th Street Bridge,[65][70] the Georgia Tech Aquatic Center's renovation into the CRC, the new Health Center,[71] the Klaus Advanced Computing Building,[65] the Molecular Science and Engineering Building,[65][70] and the (as of 2007, under construction) Nanotechnology Research Center.[70] In the 2007 "Best of Tech" issue of The Technique, students voted "construction" as Georgia Tech's worst tradition.[72]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Faculty Handbook (PDF). Georgia Insitute of Technology Office of Faculty Career Development Services. April 2007. p. 2. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Combes, Richard (1992). "Origins of Industrial Extension: A Historical Case Study" (PDF). School of Public Policy, Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2007-05-28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Georgia (GA), Fulton County: Georgia Institute of Technology Historic District". National Register of Historical Places. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

- ^ "Georgia Institute of Technology Historic District". National Park Service Atlanta. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

- ^ Lenz, Richard J. (2002). "Surrender Marker, Fort Hood, Change of Command Marker". The Civil War in Georgia, An Illustrated Travelers Guide. Sherpa Guides. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d "The Hopkins Administration, 1888-1895". "A Thousand Wheels are set in Motion": The Building of Georgia Tech at the Turn of the 20th Century, 1888-1908. Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ a b c d "The George W. Woodruff Schol of Mechanical Engineering" (PDF). The American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ^ a b Brittain, James E. (1977). "Engineers and the New South Creed: The Formation and Early Development of Georgia Tech". Technology and Culture. 18 (2). Johns Hopkins University Press: 175–201. doi:10.2307/3103955.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d "A Walk Through Tech's History". Georgia Tech Alumni Magazine Online. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ a b Mell, P.H., Jr. (1895). "CHAPTER XIX. Efforts Towards Completing the Technological School as a Department of the University of Georgia". Life of Patrick Hues Mell. Baptist Book Concern. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Friedman, S. Morgan. "The Inflation Calculator". Retrieved 2007-03-26.

- ^ a b Prospectus. Georgia School of Technology. 1888. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j McMath, Robert C. Engineering the New South: Georgia Tech 1885-1985. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "GT Buildings: GTVA-UKL999-A". Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ a b "The Georgia Tech Editorial Staff". Georgia Tech Archives Finding Aids. Georgia Tech Library. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ "The Technique" (PDF). 1911-11-17. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- ^ "Staff Manual and Style Guide" (PDF). The Technique. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "ANAK: General History". Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- ^ Shaw, Jody (2002-08-23). "What is the Technique?". The Technique. Georgia Tech Student Publications. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Biographies of the Early Presidents" (HTML). Inventory of the Early Presidents Collection, 1879-1957 (bulk 1930-1950). Georgia Tech Archives & Records Management. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- ^ a b ""Splendid Growth" - The Textile Educational Enterprise at Georgia Tech". Georgia Institute of Technology Library. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ "Polymer, Textile and Fiber Engineering: History". Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2007-05-28.

- ^ Kaddi, Chanchala (2005-09-30). "French Building has unique history, old world flavor". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ "The Hall Administration, 1895-1905" (HTML). "A Thousand Wheels are set in Motion" - The Building of Georgia Tech at the Turn of the 20th Century, 1888-1908. Georgia Tech Library and Information Center. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- ^ Edwards, Pat (1998-01-16). "Ramblins: Hall handed down stiff penalty for senior prank". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Lyman Hall Chemistry Building" (HTML). "A Thousand Wheels are set in Motion" - The Building of Georgia Tech at the Turn of the 20th Century, 1888-1908. Georgia Tech Library and Information Center. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- ^ "Lyman Hall". Campus Map. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Retrieved 2007-03-26.

- ^ a b Selman, Sean (2002-03-27). "Presidential Tour of Campus Not the First for the Institute". A Presidential Visit to Georgia Tech. Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ "One Hundred Years Ago Was Eventful Year at Tech". BuzzWords. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. 2005-10-01. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Tech Timeline". Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Retrieved 2007-03-27.

- ^ a b c "Underground Degrees". Tech Topics. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Fall 1997. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ^ a b Cuneo, Joshua (2003-04-11). "Female faculty, staff offer professional perspectives". Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ "History of Georgia State University". Georgia State University Library. 2003-10-06. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ^ a b "History". Georgia Tech Research Institute. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ Guertin, Karl (2004-02-13). "Tech's moniker reveals its true history". The Technique. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ "World War II and the Tech Connection". Tech Topics. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Spring 1995. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ "Georgia Tech History & Traditions". Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ a b Southern Polytechnic State University. "Southern Polytechnic: History".

- ^ a b Terraso, David (2003-03-21). "Georgia Tech Celebrates 50 Years of Women". Georgia Institute of Technology News Room. Retrieved 2006-11-13.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Office of Institutional Research & Planning: Facts and Figures: Enrollment by Gender". Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g Edwards, Pat (1999-09-10). "Being new to Tech was not always so easy". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- ^ a b c d "Armageddon to Go". Time. 1955-12-12. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ^ "Georgia Tech is Nation's No. 1 Producer of African-American Engineers in the Nation" (Press release). Georgia Institute of Technology. 2001-09-13. Retrieved 2006-11-13.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Nystrom, Justin (2004-04-20). "New Georgia Encyclopedia: Lester Maddox". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Georgia Humanities Council and the University of Georgia Press. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ Roberts, Allison (1999-05-21). "Buzz 1001: Giving Tech history some credit". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-06-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Joshi, Nikhil (2006-03-10). "Geibelhaus lectures on controversial president". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

There was controversy in every step. Management fought this, because they were the big losers... Crecine was under fire.

- ^ Gray, J.R. (1998-02-06). "Get over headtrip, Management". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "About Georgia Tech Lorraine". Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ Wiggins, Mindy (1997-01-17). "GT Lorraine sued over Web site". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ "GlobalVision :: Toubon Law". Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ a b "Touring the Olympic Village". Tech Topics. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Fall 1995. Retrieved 2007-05-21.

- ^ Hashmi, Shad (1998-01-30). "Management and IAC consider split". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Lange, Scott (1998-02-13). "Management split: a 'revenue-neutral' move". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Lange, Scott (1998-04-17). "Board of Regents gives IAC restructuring a nod". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Tech Wins National Teaching Award: Hesburgh Award Recognizes Innovation in Undergraduate Teaching" (Press release). Georgia Institute of Technology. 1999-02-15. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Georgia Tech Remains Strong in U.S. News Rankings" (Press release). Georgia Institute of Technology. 2006-08-18. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Student Computer Ownership Initiative". Georgia Tech Office of Information Technology. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ^ Nguyen, Leslie (1998-04-10). "Greeks connect to the Internet". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Kantor, Arcadiy (2004-08-20). "LAWN increases laptop usage". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Sanders, Jane (2001-02-16). "Learning by Doing". Georgia Tech Research News. Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2007-06-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Chen, Inn Inn (2005-09-23). "Research, International Plan Fair hits Skiles Walkway". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ Joshi, Nikhil (2005-03-04). "International plan takes root". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ a b Rutz, Christine (2002-09-13). "Tech's construction boom explained". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Baucom, Chris (1999-01-22). "Master Plan sets goals for future". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e Cuneo, Joshua (2005-07-01). "Following Master Plan, construction continues". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Kantor, Arcadiy (2004-06-11). "Tech Master Plan revised, updated". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Shaw, Jody (2001-10-05). "Institute finalizes Greek master plan". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "New Facility Honors Manufacturing Giant" (Press release). Georgia Institute of Technology. 2000-09-12. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ "A Facility for the New Millennium". Tech Topics. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Winter 1999. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ a b c Raghavan, Manu (2006-06-16). "Campus construction continues". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Reeves, Jason (2002-05-31). "Health Center finds a new home". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Best & Worst of Tech: Worst Tech Tradition" (PDF). The Technique. 2007-04-20. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)