Medicinal plants

Medicinal plants, medicinal herbs, or simply herbs have been identified and used from prehistoric times. Plants make many chemical compounds for biological functions, including defence against insects, fungi and herbivorous mammals. Over 12,000 active compounds are known to science. These chemicals work on the human body in exactly the same way as pharmaceutical drugs, so herbal medicines can be beneficial and have harmful side effects just like conventional drugs. However, since a single plant may contain many substances, the effects of taking a plant medicine can be complex.

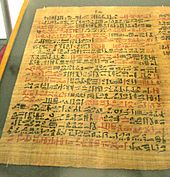

The earliest historical records of herbs are found from the Sumerian civilisation, where hundreds of medicinal plants including opium are listed on clay tablets. The Ebers Papyrus from ancient Egypt describes over 850 plant medicines, while Dioscorides documented over 1000 recipes for medicines using over 600 medicinal plants in De materia medica, forming the basis of pharmacopoeias for some 1500 years. Drug research makes use of ethnobotany to search for pharmacologically active substances in nature, and has in this way discovered hundreds of useful compounds.[2] These include the common drugs aspirin, digoxin, quinine, and opium.[3] The compounds found in plants are of many kinds, but most are in four major biochemical classes, the alkaloids, glycosides, polyphenols, and terpenes.

Medicinal plants are widely used to treat disease in non-industrialized societies, not least because they are far cheaper than modern medicines. The annual global export value of pharmaceutical plants in 2012 was over US$2.2 billion.[4]

History

Prehistoric times

Plants, including many now used as culinary herbs and spices, have been used as medicines from prehistoric times. Spices have been used partly to counter food spoilage bacteria, especially in hot climates,[6][7] and especially in meat dishes which spoil more readily.[8] Angiosperms (flowering plants) were the original source of most plant medicines.[9] Human settlements are often surrounded by weeds useful as medicines, such as nettle, dandelion and chickweed.[10][11] Humans were not alone in using herbs as medicines: some animals such as non-human primates, monarch butterflies and sheep ingest medicinal plants to treat illness.[12] Plant samples from prehistoric burial sites are among the lines of evidence that Paleolithic peoples had knowledge of herbal medicine. For instance, a 60 000-year-old Neanderthal burial site, "Shanidar IV", in northern Iraq has yielded large amounts of pollen from 8 plant species, 7 of which are used now as herbal remedies,[13] A mushroom was found in the personal effects of Ötzi the Iceman, whose body was frozen in the Ötztal Alps for more than 5,000 years. The mushroom was probably used to treat whipworm.[14]

Ancient times

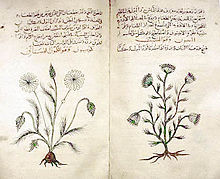

In ancient Sumeria, hundreds of medicinal plants including myrrh and opium are listed on clay tablets. The ancient Egyptian Ebers Papyrus lists over 800 plant medicines such as aloe, cannabis, castor bean, garlic, juniper, and mandrake.[15] From ancient times to the present, Ayurvedic medicine as documented in the Atharva Veda, the Rig Veda and the Sushruta Samhita has used hundreds of pharmacologically active herbs and spices such as turmeric, which contains curcumin.[16][17][18] The Chinese pharmacopoeia, the Shennong Ben Cao Jing records plant medicines such as chaulmoogra for leprosy, ephedra, and hemp.[19] This was expanded in the Tang Dynasty Yaoxing Lun.[20] In the fourth century BC, Aristotle's pupil Theophrastus wrote the first systematic botany text, Historia plantarum.[21] In the first century AD, the Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides documented over 1000 recipes for medicines using over 600 medicinal plants in De materia medica; it remained the authoritative reference on herbalism for over 1500 years, into the seventeenth century.[5]

Middle Ages

In the Early Middle Ages, Benedictine monasteries preserved medical knowledge in Europe, translating and copying classical texts and maintaining herb gardens.[22][23] Hildegard of Bingen wrote Causae et Curae ("Causes and Cures") on medicine.[24] In the Islamic Golden Age, scholars translated many classical Greek texts including Dioscorides into Arabic, adding their own commentaries.[25] Herbalism flourished in the Islamic world, particularly in Baghdad and in Al-Andalus. Among many works on medicinal plants, Abulcasis (936–1013) of Cordoba wrote The Book of Simples, and Ibn al-Baitar (1197–1248) recorded hundreds of medicinal herbs such as Aconitum, nux vomica, and tamarind in his Corpus of Simples.[26] Avicenna included many plants in his 1025 The Canon of Medicine.[27] Abu-Rayhan Biruni,[28] Ibn Zuhr,[29] Peter of Spain, and John of St Amand wrote further pharmacopoeias.[30]

Early Modern

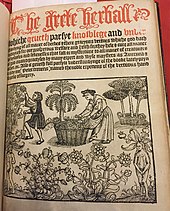

The early modern period saw the flourishing of illustrated herbals across Europe, starting with the 1526 Grete Herball. John Gerard wrote his famous The Herball or General History of Plants in 1597, based on Rembert Dodoens, and Nicholas Culpeper published his The English Physician Enlarged.[31] Many new plant medicines arrived in Europe as products of Early Modern exploration and the resulting Columbian Exchange, in which livestock, crops and technologies were transferred between the Old World and the Americas in the 15th and 16th centuries. Medicinal herbs arriving in the Americas included garlic, ginger, and turmeric; coffee, tobacco and coca travelled in the other direction.[32][33] In Mexico, the sixteenth century Badianus Manuscript described medicinal plants available in Central America.[34]

Phytochemistry

Many plants produce chemical compounds for defence against herbivores. These are often useful as drugs. The major classes of pharmacologically active phytochemicals are described below.[9][35][36][37]

Alkaloids

Alkaloids are bitter-tasting chemicals, very widespread in nature, and often toxic. There are several classes with different modes of action as drugs, both recreational and pharmaceutical. Medicines of different classes include atropine, scopolamine, and hyoscyamine (all from nightshade),[38] berberine (from plants such as Berberis and Mahonia), caffeine (Coffea), cocaine (Coca), ephedrine (Ephedra), morphine (opium poppy), nicotine (tobacco), psilocin (many psilocybin mushrooms), reserpine (Rauwolfia serpentina), quinidine and quinine (Cinchona), vincamine (Vinca minor), and vincristine (Catharanthus roseus).[37][39]

-

The alkaloid nicotine from tobacco binds directly to the body's Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, accounting for its pharmacological effects.[40]

-

Deadly nightshade, Atropa belladonna, yields tropane alkaloids including atropine, scopolamine and hyoscyamine.[38]

Glycosides

Anthraquinone glycosides are found in the laxatives senna,[41] rhubarb[42] and Aloe.[37]

The cardiac glycosides are powerful drugs from plants including foxglove and lily of the valley. They include digoxin and digitoxin which support the beating of the heart, and act as diuretics.[43]

-

Senna alexandrina, containing Anthraquinone glycosides, has been used as a laxative for millennia.[41]

-

The foxglove, Digitalis purpurea, contains digoxin, a cardiac glycoside. The plant was used to treat heart conditions long before the glycoside was identified.[43][44]

Polyphenols

Polyphenols of several classes are widespread in plants. They include the colourful anthocyanins, hormone-mimicking phytoestrogens, and astringent tannins.[46][37] In Ayurveda, the astringent rind of the pomegranate is used as a medicine,[47] while polyphenol extracts from plant materials such as grape seeds are sold for their potential health benefits despite the lack of evidence.[48][49]

Plants containing phytoestrogens have been used for centuries to treat fertility, menstrual, and menopausal problems.[50] Among these plants are Pueraria mirifica,[51] kudzu,[52] angelica,[53] fennel, and anise.[54]

Terpenes

Terpenes and terpenoids of many kinds are found in resinous plants such as the conifers. They are strongly aromatic and serve to repel herbivores. Their scent makes them useful in essential oils, whether for perfumes such as rose and lavender, or for aromatherapy.[37][55][56]

-

The essential oil of common thyme (Thymus vulgaris), contains the monoterpene thymol, an antiseptic and antifungal.[57]

In practice

Cultivation

Medicinal plants demand intensive management. Different species each require their own distinct conditions of cultivation. The World Health Organization recommends the use of rotation to minimise problems with pests and plant diseases. Cultivation may be traditional or may make use of conservation agriculture practices to maintain organic matter in the soil and to conserve water, for example with no-till farming systems.[59] In many medicinal and aromatic plants, plant characteristics vary widely with soil type and cropping strategy, so care is required to obtain satisfactory yields.[60]

Usage

Plant medicines are ubiquitous in pre-industrial societies, while some 7,000 conventional medicines such as aspirin, digitalis, opium, and quinine derive directly from traditional plant medicines, accounting for around a quarter of the modern pharmacopoeia. They are in general far cheaper, and many can be home-grown or picked for free. Further, pharmaceutical companies have made use of the herbal knowledge of indigenous peoples around the world to search for new drug candidates.[61] In India, where Ayurveda has been practised for centuries, herbal remedies are the responsibility of a government department, AYUSH, under the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare.[62] Traditional Chinese medicine makes use of a wide variety of plants, among other materials and techniques.[63] Complementary and alternative medicines including herbal therapy are widely used in the Western world, for example by over a third of Americans.[64]

Plant medicines including opiates, cocaine and cannabis have both medical and recreational uses. Different countries have at various times made some uses of drugs illegal, partly on the basis of the risks involved in taking psychoactive drugs.[65]

Effectiveness

Plant medicines have often not been tested systematically, but have come into use informally over the centuries. By 2007, clinical trials had demonstrated potentially useful activity in nearly 16% of herbal medicines; there was limited in vitro or in vivo evidence for roughly half the medicines; there was only phytochemical evidence for around 20%; 0.5% were allergenic or toxic; and some 12% had effectively never been studied scientifically.[66] According to Cancer Research UK, "there is currently no strong evidence from studies in people that herbal remedies can treat, prevent or cure cancer".[67] Modern knowledge of medicinal plants is being systematised in the Medicinal Plant Transcriptomics Database, which provides a sequence reference for the transcriptome of some thirty species.[68] There is renewed interest in the discovery of therapeutically useful substances from medicinal plants.[69]

Safety

Plant medicines can cause adverse effects and even death, whether by side-effects of their active substances, by adulteration or contamination, by overdose, or by inappropriate prescription. Many such effects are known, while others remain to be explored scientifically. There is no reason to presume that because a product comes from nature it must be safe: the existence of powerful natural poisons like atropine and nicotine shows this to be untrue. Further, the high standards applied to conventional medicines do not always apply to plant medicines, and dose can vary widely depending on the growth conditions of plants: older plants may be much more toxic than young ones, for instance.[71] Pharmacologically active plant extracts can interact with conventional drugs, both because they may provide an increased dose of similar compounds, and because some phytochemicals interfere with the body's systems that metabolise drugs in the liver including the cytochrome P450 system, making the drugs last longer in the body and have a more powerful cumulative effect.[72] Plant medicines can be dangerous during pregnancy.[73] Since plants may contain many different substances, plant extracts may have complex effects on the human body.[6]

Quality

Herbal medicines and supplements are not always tested for purity, and there is some concern about adulteration and inclusion of allergens such as soy and wheat in some products.[74]

See also

- Bach flower remedies

- Ethnomedicine

- Ethnopharmacy

- European Directive on Traditional Herbal Medicinal Products

- Herbalism

- Medicinal mushrooms

References

- ^ Lichterman, B. L. (2004). "Aspirin: The Story of a Wonder Drug". British Medical Journal. 329 (7479): 1408. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7479.1408.

- ^ "The value of plants used in traditional medicine for drug discovery". Environ. Health Perspect. 109 (Suppl 1): 69–75. March 2001. doi:10.1289/ehp.01109s169. PMC 1240543. PMID 11250806.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Swain, Tony, ed. (1968). Plants in the Development of Modern Medicine. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-67330-1.

- ^ "Medicinal and aromatic plants trade programme". Traffic.org. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ^ a b Collins, Minta (2000). Medieval Herbals: The Illustrative Traditions. University of Toronto Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-8020-8313-5.

- ^ a b "Health benefits of herbs and spices: the past, the present, the future". Med. J. Aust. 185 (4 Suppl): S4–24. August 2006. PMID 17022438.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Billing, Jennifer; Sherman, P.W. (March 1998). "Antimicrobial functions of spices: why some like it hot". Q Rev Biol. 73 (1): 3–49. doi:10.1086/420058. PMID 9586227.

- ^ Sherman, P.W.; Hash, G.A. (May 2001). "Why vegetable recipes are not very spicy". Evol Hum Behav. 22 (3): 147–163. doi:10.1016/S1090-5138(00)00068-4. PMID 11384883.

- ^ a b "Angiosperms: Division Magnoliophyta: General Features". Encyclopædia Britannica (volume 13, 15th edition). 1993. p. 609.

- ^ Stepp, John R. (June 2004). "The role of weeds as sources of pharmaceuticals". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 92 (2–3): 163–166. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2004.03.002. PMID 15137997.

- ^ Stepp, John R.; Moerman, Daniel E. (April 2001). "The importance of weeds in ethnopharmacology". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 75 (1): 19–23. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00385-8. PMID 11282438.

- ^ Sumner, Judith (2000). The Natural History of Medicinal Plants. Timber Press. p. 16. ISBN 0-88192-483-0.

- ^ Solecki, Ralph S. (November 1975). "Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal Flower Burial in Northern Iraq". Science. 190 (4217): 880–881. doi:10.1126/science.190.4217.880.

- ^ Capasso, L. (December 1998). "5300 years ago, the Ice Man used natural laxatives and antibiotics". Lancet. 352 (9143): 1864. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79939-6. PMID 9851424.

- ^ a b Sumner, Judith (2000). The Natural History of Medicinal Plants. Timber Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-88192-483-0.

- ^ "Curcumin: the Indian solid gold". Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 595: 1–75. 2007. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_1. ISBN 978-0-387-46400-8. PMID 17569205.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "Turmeric Herb". Tamilnadu.com. 15 December 2012.

- ^ Girish Dwivedi, Shridhar Dwivedi (2007). History of Medicine: Sushruta – the Clinician – Teacher par Excellence (PDF). National Informatics Centre. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ^ Sumner, Judith (2000). The Natural History of Medicinal Plants. Timber Press. p. 18. ISBN 0-88192-483-0.

- ^ Wu, Jing-Nuan (2005). An Illustrated Chinese Materia Medica. Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-19-514017-0.

- ^ Grene, Marjorie (2004). The philosophy of biology: an episodic history. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-521-64380-1.

- ^ Arsdall, Anne V. (2002). Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine. Psychology Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-415-93849-5.

- ^ Mills, Frank A. (2000). "Botany". In Johnston, William M. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Monasticism: M-Z. Taylor & Francis. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-57958-090-2.

- ^ Ramos-e-Silva Marcia (1999). "Saint Hildegard Von Bingen (1098–1179) "The Light Of Her People And Of Her Time"". International Journal Of Dermatology. 38 (4): 315–320. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00617.x.

- ^ Castleman, Michael (2001). The New Healing Herbs. Rodale. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-57954-304-4.; Collins, Minta (2000). Medieval Herbals: The Illustrative Traditions. University of Toronto Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-8020-8313-5.; "Pharmaceutics and Alchemy". US National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 26 January 2017.; Fahd, Toufic. "Botany and agriculture": 815.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help), in Rashed, Roshdi; Morelon, Régis (1996). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science: Astronomy-Theoretical and applied, v.2 Mathematics and the physical sciences; v.3 Technology, alchemy and life sciences. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-02063-3. - ^ Castleman, Michael (2001). The New Healing Herbs. Rodale. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-57954-304-4.

- ^ Jacquart, Danielle (2008). "Islamic Pharmacology in the Middle Ages: Theories and Substances". European Review. 16 (2): 219–227 [223]. doi:10.1017/S1062798708000215.

- ^ Kujundzić, E.; Masić, I. (1999). "[Al-Biruni--a universal scientist]". Med. Arh. (in Croatian). 53 (2): 117–120. PMID 10386051.

- ^ Krek, M. (1979). "The Enigma of the First Arabic Book Printed from Movable Type". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 38 (3): 203–212. doi:10.1086/372742.

- ^ "Clinical pharmacology in the Middle Ages: Principles that presage the 21st century". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 67 (5): 447–450 [448–449]. 2000. doi:10.1067/mcp.2000.106465. PMID 10824622.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ a b Singer, Charles (1923). "Herbals". The Edinburgh Review. 237: 95–112.

- ^ Nunn, Nathan; Qian, Nancy (2010). "The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 24 (2): 163–188. doi:10.1257/jep.24.2.163. JSTOR 25703506.

- ^ Heywood, Vernon H. (2012). "The role of New World biodiversity in the transformation of Mediterranean landscapes and culture" (PDF). Bocconea. 24: 69–93.

- ^ Gimmel Millie (2008). "Reading Medicine In The Codex De La Cruz Badiano". Journal Of The History Of Ideas. 69 (2): 169–192. doi:10.1353/jhi.2008.0017.

- ^ Meskin, Mark S. (2002). Phytochemicals in Nutrition and Health. CRC Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-58716-083-7.

- ^ Lanzotti, Virginia, ed. (2009). "Introduction to the different classes of natural products". Plant-Derived Natural Products: Synthesis, Function, and Application. Springer. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-387-85497-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g Elumalai, A.; Eswariah, M. Chinna (2012). "Herbalism - A Review" (PDF). International Journal of Phytotherapy. 2 (2): 96–105.

- ^ a b "Atropa Belladonna" (PDF). The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products. 1998. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Gremigni, P.; et al. (2003). "The interaction of phosphorus and potassium with seed alkaloid concentrations, yield and mineral content in narrow-leafed lupin (Lupinus angustifolius L.)". Plant and Soil. 253 (2). Heidelberg: Springer: 413–427. JSTOR 24121197.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last1=(help) - ^ "Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Introduction". IUPHAR Database. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ a b Hietala, P.; Marvola, M.; Parviainen, T.; Lainonen, H. (August 1987). "Laxative potency and acute toxicity of some anthraquinone derivatives, senna extracts and fractions of senna extracts". Pharmacology & toxicology. 61 (2): 153–6. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1987.tb01794.x. PMID 3671329.

- ^ praful akolkar. "Pharmacognosy of Rhubarb". PharmaXChange.info.

- ^ a b c "Active Plant Ingredients Used for Medicinal Purposes". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- ^ "Digitalis purpurea. Cardiac Glycoside". Texas A&M University. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

The man credited with the introduction of digitalis into the practice of medicine was William Withering.

- ^ Turner, J.V.; Agatonovic-Kustrin, S.; Glass, B.D. (Aug 2007). "Molecular aspects of phytoestrogen selective binding at estrogen receptors". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 96 (8): 1879–85. doi:10.1002/jps.20987. PMID 17518366.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Da Silva, Cecilia; et al. (2013). "The High Polyphenol Content of Grapevine Cultivar Tannat Berries Is Conferred Primarily by Genes That Are Not Shared with the Reference Genome". The Plant Cell. 25 (12). Rockville, MD: American Society of Plant Biologists: 4777–4788. JSTOR 43190600.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last1=(help) - ^ K. K. Jindal; R. C. Sharma (2004). Recent trends in horticulture in the Himalayas. Indus Publishing. ISBN 81-7387-162-0.

- ^ Halliwell, B. (2007). "Dietary polyphenols: Good, bad, or indifferent for your health?". Cardiovascular Research. 73 (2): 341–347. doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.10.004. PMID 17141749.

- ^ European Food Safety Authority (2010). "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to various food(s)/food constituent(s) and protection of cells from premature aging, antioxidant activity, antioxidant content and antioxidant properties, and protection of DNA, proteins and lipids from oxidative damage pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/20061" (PDF). EFSA Journal. 8 (2): 1489. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1489.

- ^ Muller-Schwarze, Dietland (2006). Chemical Ecology of Vertebrates. Cambridge University Press. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-521-36377-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Lee YS, Park JS, Cho SD, Son JK, Cherdshewasart W, Kang KS (Dec 2002). "Requirement of metabolic activation for estrogenic activity of Pueraria mirifica". Journal of Veterinary Science. 3 (4): 273–277. PMID 12819377.

- ^ Delmonte P, Rader JI (2006). "Analysis of isoflavones in foods and dietary supplements". Journal of AOAC International. 89 (4): 1138–46. PMID 16915857.

- ^ Brown, D.E.; Walton, N.J. (1999). Chemicals from Plants: Perspectives on Plant Secondary Products. World Scientific Publishing. pp. 21, 141. ISBN 978-981-02-2773-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Albert-Puleo M (Dec 1980). "Fennel and anise as estrogenic agents". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2 (4): 337–44. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(80)81015-4. PMID 6999244.

- ^ Tchen, T. T. (1965). "Reviewed Work: The Biosynthesis of Steroids, Terpenes & Acetogenins". American Scientist. 53 (4). Research Triangle Park, NC: Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society: 499A–500A. JSTOR 27836252.

- ^ Singsaas, Eric L. (2000). "Terpenes and the Thermotolerance of Photosynthesis". New Phytologist. 146 (1). New York: Wiley: 1–2. JSTOR 2588737.

- ^ a b "Thymol (CID=6989)". NIH. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

THYMOL is a phenol obtained from thyme oil or other volatile oils used as a stabilizer in pharmaceutical preparations, and as an antiseptic (antibacterial or antifungal) agent. It was formerly used as a vermifuge.

- ^ "Traditional Medicine. Fact Sheet No. 134". World Health Organization. May 2003. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "WHO Guidelines on Good Agricultural and Collection Practices (GACP) for Medicinal Plants". World Health Organization. 2003. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Carrubba, A.; Scalenghe, R. (2012). "Scent of Mare Nostrum ― Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (MAPs) in Mediterranean soils". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 92 (6): 1150–1170. doi:10.1002/jsfa.5630.

- ^ James A. Duke (2000). "Returning to our Medicinal Roots". Mother Earth News (December–January 2000): 26–33.; Edgar J. DaSilva; Elias Baydoun; Adnan Badran (2002). "Biotechnology and the developing world". Electronic Journal of Biotechnology. 5 (1). doi:10.2225/vol5-issue1-fulltext-1.; "Traditional medicine". Archived from the original on 2008-07-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Althea Press (2014). The Practical Herbal Medicine Handbook: Your Quick Reference Guide to Healing Herbs & Remedies. Callisto Media. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-62315-372-4.The World Health Organization has estimated that approximately 80 percent of the populations of the poorest African and Asian countries use herbal medicine as a form of primary health care, mainly because effective herbal medicines can be gathered or grown virtually cost-free.

; Khor, Kok Peng; Khor, Martin (2002). Intellectual Property, Biodiversity, and Sustainable Development: Resolving the Difficult Issues. Zed Books. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-84277-235-5. - ^ Kala, Chandra Prakash; Sajwan (2007). "Revitalizing Indian systems of herbal medicine by the National Medicinal Plants Board through institutional networking and capacity building". Current Science. 93 (6): 797–806.

- ^ "Traditional Chinese Medicine: In Depth (D428)". NIH. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "More Than One-Third of U.S. Adults Use Complementary and Alternative Medicine". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. 27 May 2004. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "Scoring drugs. A new study suggests alcohol is more harmful than heroin or crack". The Economist. 2 November 2010. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

"Drug harms in the UK: a multi-criteria decision analysis", by David Nutt, Leslie King and Lawrence Phillips, on behalf of the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs. The Lancet.

- ^ Cravotto G.; Boffa L.; Genzini L.; Garella D. (February 2010). "Phytotherapeutics: an evaluation of the potential of 1000 plants". J Clin Pharm Ther. 35 (1): 11–48. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2009.01096.x. PMID 20175810.

- ^ "Herbal medicine". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ Soejarto, D. D. (1 March 2011). "Transcriptome Characterization, Sequencing, And Assembly Of Medicinal Plants Relevant To Human Health". University of Illinois at Chicago. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ Atanasov, Atanas G.; et al. (2015). "Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: A review". Biotechnol. Adv. 33 (8): 1582–1614. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.08.001.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first1=(help) - ^ Freye, Enno (2010). Toxicity of Datura Stramonium. Springer. pp. 217–218. ISBN 978-90-481-2447-3.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Ernst, E. (1998). "Harmless Herbs? A Review of the Recent Literature" (PDF). The American Journal of Medicine. 104 (2): 170–178. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00397-5. PMID 9528737.; Talalay, P. (2001). "The importance of using scientific principles in the development of medicinal agents from plants". Academic Medicine. 76 (3): 238–47. doi:10.1097/00001888-200103000-00010. PMID 11242573.; Elvin-Lewis, M. (2001). "Should we be concerned about herbal remedies". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 75 (2–3): 141–164. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00394-9. PMID 11297844.; Vickers, A. J. (2007). "Which botanicals or other unconventional anticancer agents should we take to clinical trial?". J Soc Integr Oncol. 5 (3): 125–9. doi:10.2310/7200.2007.011. PMC 2590766. PMID 17761132.; Ernst, E. (2007). "Herbal medicines: balancing benefits and risks". Novartis Found. Symp. Novartis Foundation Symposia. 282: 154–67, discussion 167–72, 212–8. doi:10.1002/9780470319444.ch11. ISBN 978-0-470-31944-4. PMID 17913230.; Pinn, G. (November 2001). "Adverse effects associated with herbal medicine". Aust Fam Physician. 30 (11): 1070–5. PMID 11759460.

- ^ Nekvindová, J.; Anzenbacher, P. (July 2007). "Interactions of food and dietary supplements with drug metabolising cytochrome P450 enzymes". Ceska Slov Farm. 56 (4): 165–73. PMID 17969314.

- ^ Born, D.; Barron, ML (May 2005). "Herb use in pregnancy: what nurses should know". MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 30 (3): 201–6. doi:10.1097/00005721-200505000-00009. PMID 15867682.

- ^ O'Connor, Anahad. "Herbal Supplements Are Often Not What They Seem". New York Times. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

Further reading

- Aronson, Jeffrey K. (2008). Meyler's Side Effects of Herbal Medicines. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-093290-3.

- Braun, Lesley; Cohen, Marc (2007). Herbs and Natural Supplements: An Evidence-Based Guide. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7295-3796-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Crellin, J.K .; et al. (1990). Herbal Medicine Past and Present: A reference guide to medicinal plants. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-1019-8.

- Lewis, Walter H. (2003). Medical Botany: Plants Affecting Human Health. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-62882-8.

- Newall, Carol A.; et al. (1996). Herbal medicines: a guide for health-care professionals. Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85369-289-8.

- Pulikkottil, Anil J. (2012). Encyclopedia of Ayurvedic Medicinal Plants: Details about Medicinal Plants and Its usage. Indian. ISBN 978-81-930807-0-2.

![The opium poppy Papaver somniferum is the source of the alkaloids morphine and codeine.[37]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/87/Opium_poppy.jpg/160px-Opium_poppy.jpg)

![The alkaloid nicotine from tobacco binds directly to the body's Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, accounting for its pharmacological effects.[40]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/70/Nicotine.svg/143px-Nicotine.svg.png)

![Deadly nightshade, Atropa belladonna, yields tropane alkaloids including atropine, scopolamine and hyoscyamine.[38]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b7/Atropa_belladonna_-_K%C3%B6hler%E2%80%93s_Medizinal-Pflanzen-018.jpg/104px-Atropa_belladonna_-_K%C3%B6hler%E2%80%93s_Medizinal-Pflanzen-018.jpg)

![Senna alexandrina, containing Anthraquinone glycosides, has been used as a laxative for millennia.[41]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/61/Senna_alexandrina_Mill.-Cassia_angustifolia_L._%28Senna_Plant%29.jpg/161px-Senna_alexandrina_Mill.-Cassia_angustifolia_L._%28Senna_Plant%29.jpg)

![The foxglove, Digitalis purpurea, contains digoxin, a cardiac glycoside. The plant was used to treat heart conditions long before the glycoside was identified.[43][44]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/74/Digitalis_purpurea2.jpg/90px-Digitalis_purpurea2.jpg)

![Digoxin is used to treat atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter and sometimes heart failure.[43]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4d/Digoxin.svg/200px-Digoxin.svg.png)

![The essential oil of common thyme (Thymus vulgaris), contains the monoterpene thymol, an antiseptic and antifungal.[57]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fe/Thymian.jpg/181px-Thymian.jpg)

![Thymol is one of many terpenes found in plants.[57]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5d/Thymol2.svg/97px-Thymol2.svg.png)