'Adud al-Dawla

| Adud al-Dawla | |

|---|---|

| King of Kings (Persian: Šāhanšāh) | |

Medallion of Adud al-Dawla | |

| Emir of Fars | |

| Reign | 949–983 |

| Predecessor | Imad al-Dawla |

| Successor | Sharaf al-Dawla |

| Emir of Kerman | |

| Reign | 967–983 |

| Predecessor | Mu'izz al-Dawla |

| Successor | Sharaf al-Dawla |

| Emir of Iraq and Jazira | |

| Reign | 978–983 |

| Predecessor | Izz al-Dawla |

| Successor | Samsam al-Dawla |

| Born | September 24, 936 Isfahan |

| Died | March 26, 983 Baghdad |

| Burial | |

| Consort | Sayyida bint Siyahgil |

| Issue | Sharaf al-Dawla Samsam al-Dawla Baha' al-Dawla Shahnaz |

| Father | Rukn al-Dawla |

| Mother | Firuzanid noblewoman |

| Religion | Shia Islam |

Fannā (Panāh) Khusraw (Template:Lang-fa), better known by his laqab of ʿAḍud al-Dawla (Template:Lang-ar, "Pillar of the [Abbasid] Dynasty") (September 24, 936 – March 26, 983) was an emir of the Buyid dynasty, ruling from 949 to 983, and at his height of power ruling an empire stretching from Makran as far to Yemen and the shores of the Mediterranean Sea. He is widely regarded as the greatest monarch of the dynasty, and by the end of his reign was the most powerful ruler in the Middle East.[1]

The son of Rukn al-Dawla, Fanna Khusraw was given the title of Adud al-Dawla by the Abbasid caliph in 948 when he was made emir of Fars after the death of his childless uncle Imad al-Dawla, after which Rukn al-Dawla became the senior emir of the Buyids. In 974 Adud al-Dawla was sent by his father to save his cousin Izz al-Dawla from a rebellion. After defeating the rebel forces, he claimed the emirate of Iraq for himself, and forced his cousin to abdicate. His father, however, became angered by this decision and restored Izz al-Dawla. After the death of Adud al-Dawla's father, his cousin rebelled against him, but was defeated. Adud al-Dawla became afterwards the sole ruler of the Buyid dynasty and assumed the Persian title Shahanshah ("King of Kings").[2][3]

When Adud al-Dawla became emir of Iraq, the capital city, Baghdad, was suffering from violence and instability owing to sectarian conflict. In order to bring peace and stability to the city, he ordered the banning of public demonstrations and polemics. At the same time, he patronized a number of Shia scholars such as al-Mufid, and sponsored the renovation of a number of important Shia shrines.

In addition, 'Adud al-Dawla is credited with sponsoring and patronizing other scientific projects during his time. An observatory was built by his orders in Isfahan where Azophi worked. Al-Muqaddasi also reports that he ordered the construction of a great dam between Shiraz and Estakhr in 960. The dam irrigated some 300 villages in Fars province and became known as Band-e Amir (Dam of the emir). Among his other major constructions was the digging of the Haffar channel, that joined the Karun river to the Shatt al-Arab river (the confluence of the Tigris and the Euphrates). The port of Khorramshahr was built on the Haffar, at its joining point with the Shatt al-Arab.

Early life

Fanna Khusraw was born in Isfahan on September 24, 936,[1] he was the son of Rukn al-Dawla, who was the brother of Imad al-Dawla and Mu'izz al-Dawla. According to Ibn Isfandiyar, Fanna Khusraw's mother was the daughter of the Daylamite Firuzanid nobleman al-Hasan ibn al-Fairuzan, who was the cousin of the prominent Daylamite military leader Makan ibn Kaki.[4]

Reign

Rule in Fars

In 948, Fanna Khusraw was chosen by his uncle Imad al-Dawla as his successor because he had no heir. Imad al-Dawla died in December 949, and thus Fanna Khusraw became the new ruler of Fars. However, this appointment was not accepted by a group of Daylamite officers, who shortly rebelled against Fanna Khusraw. Rukn al-Dawla quickly left for southern Iran to save his son, and was joined by the vizier of Mu'izz al-Dawla for the same purpose. Together they defeated the rebels and put Fanna Khusraw on the throne in Shiraz. Fanna Khusraw then requested the title of "Taj al-Dawla" (Crown of the state) from the Abbasid caliph. However, to Mu'izz al-Dawla, the title of "Taj" ("crown") implied that Fanna Khusraw was the superior ruler of the Buyid Empire, provoking a reaction from him, and making him decline Fanna Khusraw's request. A more suitable title ("Adud al-Dawla") ("Pillar of the [Abbasid] Dynasty") was instead chosen.[5][1] Adud al-Dawla was only thirteen when he was crowned as the ruler of Fars, and was educated there by his tutor Abu 'l-Fadl ibn al-'Amid.[6]

After the death of Imad al-Dawla in 949, Adud al-Dawla's father Rukn al-Dawla, who was the most powerful of the Buyid rulers, claimed the title of senior emir, which Mu'izz al-Dawla and Adud al-Dawla recognized. In 955, a Daylamite military officer named Muhammad ibn Makan seized Isfahan from Rukn al-Dawla. Adud al-Dawla then marched towards the city and recaptured it from Muhammad ibn Makan.[7] Another Daylamite military officer named Ruzbahan also shortly rebelled against Mu'izz al-Dawla, while his brother Bullaka rebelled against Adud al-Dawla at Shiraz. Abu 'l-Fadl ibn al-'Amid, however, managed to suppress the rebellion.[1]

In 966, Adud al-Dawla and Mu'izz al-Dawla made a campaign to impose Buyid rule in Oman. Mu'izz al-Dawla died in 967, and was succeeded by his eldest son Izz al-Dawla as emir of Iraq. The same year, Adud al-Dawla aided the Ziyarid Bisutun in securing the Ziyarid throne from his brother Qabus. Adud al-Dawla and Bisutun then made an alliance, and Bisutun married a daughter of Adud al-Dawla,[8] while he married a daughter of Bisutun.[9]

Campaigns in eastern Iran

In 967, Adud al-Dawla took advantage of the quarrel between the Ilyasid ruler Muhammad ibn Ilyas and his son in Kerman to annex the province to his domain. Mu'izz al-Dawla had already attempted to conquer the province but was defeated by the Ilyasids. Adud al-Dawla conquered all of Kerman, and appointed his son Shirdil Abu'l-Fawaris as the viceroy of the province,[10] while a Daylamite officer named Kurkir ibn Justan was appointed as the chief captain of the army of Kerman.[11]

In the next year, Adud al-Dawla negotiated peace with the Saffarid ruler Khalaf ibn Ahmad, who agreed to recognize Buyid authority.[7] In 969/970, Sulaiman, the son of Muhammad ibn Ilyas, wanted to regain his kingdom of Kerman, and invaded the region. Adud al-Dawla managed to defeat the army of Sulaiman and continued to expand his domains to the strait of Hormuz.[1] During his campaign in southern Iran, many Iranian tribes converted to Islam and pledged allegiance to him. On August/September 971, Adud al-Dawla launched a punitive expedition against the Baloch tribes who had declared independence. Adud al-Dawla defeated them on January 8, 972, and installed loyal landowners to control the region. Afterwards, Adud al-Dawla and his father Rukn al-Dawla signed a peace treaty with the Samanids by paying them 150,000 dinars. In the same year, Adud al-Dawla conquered most of Oman, including its capital, Sohar.[1]

Rebellion of Sebük-Tegin and aftermath

In 974, Izz al-Dawla was trapped in Wasit by his troops who under leader Sebük-Tegin had rebelled against him. Adud al-Dawla quickly left Fars to quell the rebellion, where he inflicted a decisive defeat on the rebels on January 30, 975, who under their new leader Alptakin fled to Syria.[12] Adud al-Dawla then made a plot which forced Izz al-Dawla to abdicate in his favor on March 12, 975.[1] Rukn al-Dawla, greatly angered at this action, protested against Adud al-Dawla, claiming that the line of Mu'izz al-Dawla could not be removed from power. Adud al-Dawla tried to make an agreement with his father by proposing to pay tribute to him. Rukn al-Dawla, however, rejected his offer, and then restored Izz al-Dawla as the ruler of Iraq. The consequences of the restoration of Izz al-Dawla would later lead to war between him and Adud al-Dawla after the death of Rukn al-Dawla.[1]

In 975 Adud al-Dawla launched an expedition to take Bam and defeated another son of Muhammad ibn Ilyas who sought to reconquer to Kerman.[1]

Struggle for power in Iraq and war with the Hamdanids

On September 16, 976, Rukn al-Dawla, the last of the first generation Buyids, died. After his death, Izz al-Dawla prepared to take revenge against Adud al-Dawla. He made an alliance with Fakhr al-Dawla, the brother of Adud al-Dawla and his father's successor to the territories around Hamadan. He also made an alliance with the Hamdanids prevailing in northern Iraq, the Hasanwayhid ruler Hasanwayh and the ruler of the marshy areas of southern Iraq. However, Mu'ayyad al-Dawla, the third son of Rukn al-Dawla, remained loyal to his eldest brother.[1]

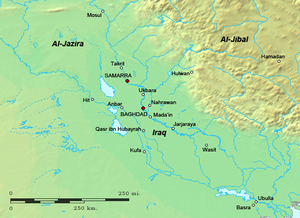

Izz al-Dawla then stopped recognizing the rule of his cousin Adud al-Dawla, and stopped mentioning his name during Friday prayers. Adud al-Dawla, greatly outraged by his cousin, marched towards Khuzestan and easily defeated him in Ahvaz on July 1, 977. Izz al-Dawla then asked Adud al-Dawla for permission to retire and settle in Syria. However, on the road to Syria, Izz al-Dawla became convinced by Abu Taghlib, the Hamdanid ruler of Mosul, to go fight again against his cousin. On May 29, 978, Izz al-Dawla along with Abu Taghlib invaded the domains of his Adud al-Dawla and fought against him near Samarra. Izz al-Dawla was once again defeated, and was captured and executed at the orders of Adud al-Dawla.[6][13]

He then marched to Mosul and captured the city,[14] which forced Abu Taghlib to flee to the Byzantine city of Anzitene, where he asked for aid. Adud al-Dawla then spent one year in Mosul to consolidate his power, while his army were completing the conquest of Diyar Bakr and Diyar Mudar;[7] The important Hamdanid city of Mayyafariqin was shortly captured by them, which forced Abu Taghlib to flee to Rahba from where he tried to negotiate peace with Adud al-Dawla.[15] Unlike the rest of the Buyids who had held the region temporarily, Adud al-Dawla had complete control of the region during the rest of his reign.

Adud al-Dawla, now the ruler of Iraq, then took control of the territories under the control of the Bedouins and Kurds. He also killed almost all the sons of Hasanwayh, and appointed Badr ibn Hasanwayh, the last surviving son of Hasanwayh, as the ruler of the Hasanwayhid dynasty.[16] It should be understood that during that period the word "Kurd" meant nomad.[1] He then subdued the Shayban tribe, and fought against Hasan ibn 'Imran, the ruler of Batihah. He was, however, defeated, and made peace with Hasan who agreed to recognize his authority. During the same period, Adud al-Dawla had Izz al-Dawla's former vizier Ibn Baqiyya arrested, blinded, and then trampled to death by elephants. His corpse was thereafter impaled at the head of the bridge in Baghdad, where it would remain until Adud al-Dawla's death.[17]

War in northern Iran

During the same period, Bisutun died, and his kingdom was thrown into civil war; his governor of Tabaristan, Dubaj ibn Bani, supported his son as the new Ziyarid ruler, while Bisutun's brother Qabus claimed the throne for himself. Adud al-Dawla quickly sent an army to aid Qabus against Dubaj. Qabus managed to defeat him and capture the son of Bisutun in Simnan. Adud al-Dawla then made the Abbasid caliph give Qabus the title of Shams al-Ma'ali.[18]

In May 979, Adud al-Dawla invaded the territories of his brother Fakhr al-Dawla, who was forced to flee to Qazvin and then to Nishapur, a large part of his troops deserted. Adud al-Dawla then moved to Kerman and later Kermanshah where he set up a governor. In August/September 980, Adud al-Dawla captured Hamadan and occupied the entire area south of the city which would remain in Buyid hands in half a century.

Shortly after, on October/November of the same year, Sahib ibn Abbad, the vizier of Adud al-Dawla's younger brother Mu'ayyad al-Dawla, arrived from Ray to negotiate a transfer of power in the city in favor of his master. Adud al-Dawla, recognized his younger brother Mu'ayyad because of his loyalty, and gave him the troops of Fakhr al-Dawla and helped him conquer Tabaristan and Gorgan from Qabus who had betrayed Adud al-Dawla by giving refugee to Fakhr al-Dawla. Mu'ayyad al-Dawla shortly managed to conquer these two provinces.[1]

Consolidation of the Empire and peace negotiations with the Byzantines

Adud al-Dawla was now the senior ruler of the Buyid Empire, and several rulers such as the Hamdanids, Saffarids, Shahinids, Hasanwayhids and even other lesser rulers who controlled Yemen, including its surrounding regions, acknowledged his authority.[16][1] Other regions such as Makran, was also under Buyid control.[16]

Adud al-Dawla then returned to Baghdad, where he built and restored several buildings in the city. He also stopped the quarrel between the Daylamites and Turks of the Buyid army.[19] In 980, the Byzantine rebel Bardas Skleros fled to Mayyafariqin. When he arrived to the city, he sent his brother to Baghdad to offer his alliegence to Adud al-Dawla and make an alliance against the Byzantines, which Adud al-Dawla accepted. A Byzantine envoy from Constantinople shortly arrived to Baghdad and tried to persuade Adud al-Dawla to hand over the rebel, but he refused and kept the rebel and some of his family members in Baghdad for the rest of his reign, thus standing in a strong position for his diplomacy with the Byzantines.[20] In 981, Adud al-Dawla sent Abu Bakr Baqillani to Constantinople to negotiate for peace. However, he was most likely sent to spy on the Byzantines and how their military functioned, since Adud al-Dawla was planning to invade Byzantine territory.[20]

In 982, Adud al-Dawla sent another envoy to Constantinople, this time under Abu Ishaq ibn Shahram, who after having spent three months in the city, concluded a 10-year peace treaty with them. One year later, a Byzantine envoy arrived back in Baghdad, but Adud al-Dawla was too ill to bring an end to the negotiations. In the end, the 10-year peace treaty was finally completed, and the Byzantines also agreed to mention Adud al-Dawla's name in the Friday prayer in Constantinople. Sahib ibn Abbad, is known to have said the following thing about this event: "he [Adud al-Dawla] has done what no kings of the Arabs nor any Chosroes [kings] of the Persians could – he has Syria and the two Iraqs, and he is close to the Despot of Byzantium and the Maghribi by his continuous correspondence."[21]

Administration and contributions

Adud al-Dawla kept his court in Shiraz. He visited Baghdad frequently and kept some of his viziers there, one of them being a Christian named Nasir ibn Harun.[1] Furthermore, he had several Zoroastrian statesmen who served him, such as Abu Sahl Sa'id ibn Fadl al-Majusi, who served as his representative of Baghdad before his conquest of Iraq; Abu'l-Faraj Mansur ibn Sahl al-Majusi, who served as his financial minister; and Bahram ibn Ardashir al-Majusi, who served as a Buyid official. Adud al-Dawla seems to have greatly respected their religion.[22]

Under him the Buyid kingdom flourished. His policies were liberal so there were no riots during his reign. He embellished Baghdad with numerous public buildings. He also built a famous public hospital known as the al-'Adudi Hospital. It was the largest hospital of that time, and was destroyed during the Mongol conquests.[1] Many prominent figures worked at the hospital, such as 'Ali ibn al-'Abbas al-Majusi and Ibn Marzuban.[23][24]

Adud al-Dawla also build caravanserai's and dams. The city that has particularly benefited from this work is Shiraz. In the region of Shiraz, he built a palace with three hundred and sixty rooms with advanced wind towers for air conditioning system of residential rooms. The population of Shiraz had increased so much during his reign that he built a satellite city near the city for his army. The name of the city was Kard-i Fannā Khusraw ("made by Fanna Khusraw"), making a clear reference to the names that the Sasanians gave their foundations.[1]

There were two annual festivals in the city. The first to commemorate the day when the water pipe reached the city and the second to recall the date of the founding of the city. Both celebrations were instituted by Adud al-Dawla on the model of the holiday of Nowruz, the Iranian New Year.[1]

All these activities greatly expanded the economy of Fars so that the tax income was tripled in the 10th-century. His contributions to the enrichment of Fars made it a region of relative stability and prosperity for the culture of Iran during the Seljuq and Mongol invasions.[1]

Family

Adud al-Dawla, in order to maintain peace, established marriage ties with several rulers;[9] his daughter was married to the Abbasid caliph at-Ta'i, while another was married to the Samanids and the Ziyarid ruler Bisutun. Adud al-Dawla himself had several wives, which included; the daughter of Bisutun; the daughter of Manadhar, an Justanid king; and the daughter of Siyahgil, an Giilite king. From these wives, Adud al-Dawla had several sons; Abu'l-Husain Ahmad and Abu Tahir Firuzshah, from the daughter of Manadhar; Abu Kalijar Marzuban, from the daughter of Siyahgil; and Shirdil Abu'l-Fawaris, from a Turkic concubine. Adud al-Dawla also had a younger son named Baha' al-Dawla. Abu'l-Husain Ahmad was supported by his mother and his uncle Fuladh ibn Manadhar as the heir of the Buyid Empire. However, Abu Kalijar Marzuban, because of his more prominent descent, was appointed as heir of the Buyid Empire by Adud al-Dawla.

Ancestry

| Family of 'Adud al-Dawla | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Death and succession

Adud al-Dawla died at Baghdad on March 26, 983,[1] and was buried in Najaf. His son Abu Kalijar Marzuban, who was in Baghdad at the time of his death, first kept his death secret in order to ensure his succession and avoid civil war. When he made the death of his father public, he was given the title of "Samsam al-Dawla". However, Adud al-Dawla's other son, Shirdil Abu'l-Fawaris, challenged the authority of Samsam al-Dawla, resulting in a civil war.[26]

Legacy

Adud al-Dawla, like the previous Buyid rulers, maintained the Abbasids in Baghdad, which gave legitimacy to his dynasty in the eyes of some Sunni Muslims. However, he showed more interest than his predecessors to the pre-Islamic culture of Iran, and was proud of his Iranian origin.[27] He visited Persepolis alongside Marasfand, the Zoroastrian chief priest (mobad) of Kazerun,[22] who read the pre-Islamic inscriptions in the city for him. Adud al-Dawla later left an inscription in the city, which tells about his awareness of being heir of an ancient pre-Islamic civilization. Adud al-Dawla even claimed descent from the Sasanian king Bahram V Gor,[28] minted coins of him wearing a Sasanian type crown, and carried the traditional Sasanian inscription; Shahanshah, may his glory increase. While the reverse side of the coin said: May Shah Fanna Khusraw live long.[29]

However, he still preferred Arabic authors more than Persian ones. There is very little evidence which shows his interest in Persian poetry. He spoke Arabic, wrote in Arabic and was proud to be a student of a famous Arab grammarian. He studied science in Arabic, including astronomy and mathematics. Many books written in Arabic were dedicated to him whether religious or secular content. Apparently showing interest in Arabic rather than Persian, Adud al-Dawla followed the mainstream of intellectual life in a provincial town where culture was dominated by Arabic and Persian.[1]

Like many of his contemporaries, he does not seem to have felt that his admiration for the pre-Islamic Iranian civilization conflicted with his Muslim Shiite faith. According to some accounts, he repaired the Imam Husayn Shrine in Karbala, and built a mausoleum of Ali in Najaf, which is today known as the Imam Ali Mosque. He is said to have been generous to a prominent Shiite theologian, but did not follow a Shiite religious policy and was tolerant to the Sunnis. He even tried to get closer to the Sunnis by giving his daughter in marriage to the caliph, which was a failure because the caliph refused to consummate the marriage.[1]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Ch. Bürgel & R. Mottahedeh 1988, pp. 265–269.

- ^ Patrick Clawson & Michael Rubin 2005, p. 19.

- ^ Bosworth 1975, p. 275.

- ^ a b Ibn Isfandiyar 1905, pp. 204–270.

- ^ Bosworth 1975, p. 263.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, p. 230.

- ^ a b c Donohue 2003, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Madelung 1975, p. 214.

- ^ a b Donohue 2003, pp. 86–93.

- ^ Bosworth 1975, p. 266.

- ^ Amedroz & Margoliouth 1921, p. 271.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 224.

- ^ Taylor & Francis 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 272, 230.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 272.

- ^ a b c Bosworth 1975, p. 270.

- ^ Donohue 2003, p. 158.

- ^ Madelung 1975, p. 215.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 233.

- ^ a b Donohue 2003, pp. 77–79.

- ^ Donohue 2003, pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b Donohue 2003, p. 81.

- ^ Dunlop 1997, p. 39.

- ^ Richter-Bernburg 1985, pp. 837–838.

- ^ Nagel 1990, pp. 578–586.

- ^ Bosworth 1975, p. 289.

- ^ Donohue 2003, p. 85.

- ^ Bosworth 1975, p. 274.

- ^ Donohue 2003, p. 22.

Sources

- Dunlop, D. M. (1997). "EBN MARZOBĀN, ABŪ AḤMAD ʿABD-AL-RAḤMĀN". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VIII, Fasc. 1. D. M. Dunlop. p. 39.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Richter-Bernburg, L. (1985). "ʿALĪ B. ʿABBĀS MAJŪSĪ". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VI, Fasc. 8. D. M. Dunlop. pp. 837–838.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Madelung, W. (1975). "The Minor Dynasties of Northern Iran". In Frye, R.N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 198–249. ISBN 978-0-521-20093-6.

- Hill, Donald Routledge, Islamic Science And Engineering, Edinburgh University Press (1993), ISBN 0-7486-0455-3

- Edward Granville Browne, Islamic Medicine, 2002, ISBN 81-87570-19-9

- Bosworth, C. E. (1975). "Iran under the Buyids". In Frye, R. N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 250–305. ISBN 0-521-20093-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nagel, Tilman (1990). "BUYIDS". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 6. London u.a.: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 578–586.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Taylor &, Francis (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: A-K, index. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kennedy, Hugh N. (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Ltd. ISBN 0-582-40525-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ch. Bürgel; R. Mottahedeh (1988). "ʿAŻOD-AL-DAWLA, ABŪ ŠOJĀʾ FANNĀ ḴOSROW". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 3. London u.a.: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 265–269.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Donohue, John J. (2003). The Buwayhid Dynasty in Iraq 334h., 945 to 403h., 1012: Shaping Institutions for the Future. ISBN 978-90-04-12860-6. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kabir, Mafizullah (1964). The Buwayhid Dynasty of Baghdad, 334/946-447/1055. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Patrick Clawson &, Michael Rubin (2005). Eternal Iran: Continuity and Chaos. ISBN 1-4039-6276-6. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilferd Madelung, Wolfgang Felix, (1995). "DEYLAMITES". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. BII, Fasc. 4. pp. 342–347.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ibn, Isfandiyar (1905). An Abridged Translation of the History of Tabaristan. University of Michigan: BRILL. pp. 1–356. ISBN 978-90-04-09367-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kraemer, Joel L. (1992). Humanism in the Renaissance of Islam: The Cultural Revival During the Buyid Age. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-09736-0.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Amedroz, Henry F.; Margoliouth, David S., eds. (1921). The Eclipse of the 'Abbasid Caliphate. Original Chronicles of the Fourth Islamic Century, Vol. V: The concluding portion of The Experiences of Nations by Miskawaihi, Vol. II: Reigns of Muttaqi, Mustakfi, Muti and Ta'i. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)