1975 British Mount Everest Southwest Face expedition

The 1975 British Mount Everest Southwest Face expedition was the first to successfully climb Mount Everest by ascending one of its faces. In the post-monsoon season Chris Bonington led the expedition which used rock climbing techniques to put fixed ropes up the face from the Western Cwm to just below the South Summit. A key aspect of the success of the climb was the scaling of the cliffs of the Rock Band at about 8,200 metres (27,000 ft) by Nick Estcourt and Tut Braithwaite. Two teams then climbed to the South Summit and followed the Southeast Ridge to the main summit – Dougal Haston with Doug Scott on 24 September 1975, who at the South Summit made the highest ever bivouac for that time, and Peter Boardman with Pertemba two days later. It is thought that Mick Burke fell to his death shortly after he had also reached the top. British climbers reached the summit of Everest for the first time in an event that has been described as "the apotheosis of the big, military-style expeditions".

Background

Rock climbing in Britain after World War II

After years of stagnation between the wars, British rock climbing underwent a renaissance, particularly with working-class climbing clubs starting up in the north of England and Scotland. The Rock and Ice Club in Manchester, the Creagh Dhu Mountaineering Club in Glasgow and several university climbing clubs were amongst those that engendered a highly competitive climbing environment. At Clogwyn Du'r Arddu in Wales numerous routes of a very high standard were achieved using strictly free climbing techniques. Hamish MacInnes and Dougal Haston, although not members, climbed with Creagh Dhu. MacInnes had mentored Bonington's youthful climbing as early as 1953. These associations led on to spectacular exploits such as the American-led direttissima route up the North Face of the Eiger in the winter of 1966 (including Haston[note 2]) and the televised climbing of the Old Man of Hoy in Orkney in the following year (including Bonington and Haston[note 3]). The public took notice and commercial sponsorship started to become a possibility for even more elaborate expeditions but with an ultimate aim of rock climbing. With all the 8000-metre peaks climbed by 1964, climbing in Himalaya using rock climbing routes became an aspiration.[4]

Bonington's path to Everest

Bonington's climbing career began when he was still in his teens and he soon was achieving technically difficult ascents in the Alps with several first ascents and, in 1962, the first ascent by a Briton of the Eiger's Nordwand. He made first ascents of Annapurna II (1960) and Nuptse (1962). His role as climbing photo-journalist on the "Eiger direttissima" in 1966 bought him widespread attention and he was encouraged to mount his own expedition.[5]

Bonington conceived of the idea of climbing Annapurna by its South Face which he realised was going to require siege tactics as well as rock climbing. This 1970 expedition involved Haston as well as such climbers as Don Whillans, Mick Burke, Nick Estcourt, Martin Boysen and Ian Clough who was killed during the descent.[4] The expedition was a huge success because not only was the summit reached but it was, for its time, the most difficult technical climb to the summit of a major world peak.[6] Bonington had very much been the leader and had not personally attempted to reach the summit. He was a good communicator and he had been able to attract sponsorship and maintain a group of highly proficient yet individualistic climbers as a coherent team.[5]

Seizing an opportunity for an Everest expedition post-monsoon in 1972, Bonington originally planned a lightweight expedition by the normal route but the failure of the European pre-monsoon Southwest Face expedition earlier in that year encouraged him to attempt the Southwest Face instead. In very poor weather Bonington's expedition failed to reach the summit but the team gained a great deal of experience, in particular discovering that the line above Camp 6 was not as favourable as they had anticipated.[7]

Bonington decided not to make any further post-monsoon attempts and, before the expedition left Kathmandu, he booked the next available time slot which was for 1979.[8] A while later, after learning that a British Army team was planning a pre-monsoon 1976 expedition, Bonington tried to persuade them to allow his team to be included. However, his suggestion was rejected.[9]

Climbing on Everest prior to 1975

Routes climbed

After the 1921 British reconnaissance, attempts to climb Everest had been from Tibet because Nepal was closed to foreign climbers. Then, in 1950, Tibet's borders were closed when it was occupied by the People's Republic of China and by that time no expedition had been able to reach the summit. Partly on account of the political situation in Tibet, Nepal started allowing climbers entry in 1950 although it closed its frontiers again in 1966. During the period 1950–1966 three ridge routes were pioneered to reach the summit – the South Col—Southeast Ridge (1953), West Ridge—Hornbein Couloir (1963) and by a Chinese team via the North Col—North Ridge (1960). However, no summit attempt had been made on routes up any of Everest's faces.[10] Nepal again allowed entry to climbers in 1969 and the Southwest Face, the only face accessible from Nepal, was such an attractive objective that Japan immediately mounted a spring reconnaissance in that year and returned in the autumn with a larger party with several climbers reaching 8,000 metres (26,000 ft) on a line striking left from the central gully (black—cyan route on the diagram below).[11]

Previous summit attempts using the Southwest Face

Spring 1970 Japanese expedition – the expedition climbed no higher than in the previous year (black—cyan route on the diagram). However, led by Saburo Matsukata, a party reached the summit via the South Col.[12]

Spring 1971 International expedition – led by Norman Dyhrenfurth, the expedition reached 8,350 metres (27,400 ft) (attained by Haston and Whillans) on a new line leading to the right above Camp 5 (black—blue—brown route).[13]

Spring 1972 European expedition – Felix Kuen and Adolf Huber reached about 8,300 metres (27,200 ft) in an expedition led by Karl Herrligkoffer (black—blue—green route).[14]

Autumn 1972 British expedition – on the Bonington-led expedition 8,300 metres (27,200 ft) was reached by Bonington, Ang Phu, MacInnes, Scott, Burke and Haston (black—blue route).[14]

Autumn 1973 Japanese expedition – 8,300 metres (27,200 ft) was reached on the Southwest Face (black—blue route) but the expedition did reach the summit by the South Col. The expedition was led by Michio Yuasa and it was the first time Everest had been climbed after the monsoon.[15]

Genesis of the 1975 expedition

The post-monsoon Japanese expedition in 1973 had attempted both the Southwest Face and the normal route. The face party had failed in much the same way as the British had the year before but the South Col team had managed what turned out to be a very significant achievement. In the post-monsoon season they had reached the summit by climbing directly from the South Col without stopping overnight. By the time they had reached the summit they were out of oxygen but despite that, and having to bivouac overnight without food, drink or a tent, they had returned safely to the South Col.[16]

In December 1973 Bonington heard that a team had withdrawn from its 1975 time slot. It was for post-monsoon so when he applied for the slot he was again intending to attempt his lightweight South Col—Southeast Ridge scheme. Permission was given in April 1974 when he, Haston and Scott were starting on a Changabang expedition (which was to be another first ascent) and Haston and Scott were able to persuade Bonington to try the Southwest Face again, despite it having to be in the autumn.[17][18] The scheme eventually turned into what has been described as "the apotheosis of the big, military-style expeditions".[19]

Preparations

A lesson learned from the 1973 Japanese expedition was that any attempt should be as early as possible after the monsoon was over and this meant the trek from Kathmandu to Base Camp had to be during the monsoon. Another attempt using the "Whillans Chimney" above Camp 6 would have meant establishing a seventh camp and so a route to the left of the Great Central Gully would be taken on the same line that the earliest Japanese climbers had tried. Camp 6 would be established on the upper snowfield and a long traverse would be taken to the Southeast Ridge. To complete the traverse, climb the ridge, and return would be a very long day – a bivouac on the return might well be necessary. To get into a position to do this a large support team would need to make a rapid ascent up the central gully so very careful logistical planning would be necessary.[20]

Supplementary oxygen would be used above Camp 4 for climbers and Camp 5 for Sherpas and 4,000 metres (13,000 ft) of fixed rope would be used up the face (fixed rope in the Icefall and climbing rope would be additional).[21]

A management committee, chaired by Lord Hunt (John Hunt of the 1953 British Mount Everest expedition), was set up for what would be an expensive, siege-style operation.[22] Peter Boardman was later to remark "for a mountaineer, surely a Bonington Everest expedition is one of the last great Imperial experiences life can offer."[23] Bonington and his agent knew a director of Barclays Bank International and they approached him to see if the bank would provide sponsorship. Barclays not only agreed to provide the £100,000 requested but agreed to cover any overspend. This caused complaints from customers of the bank and a question was asked in Parliament.[24]

Logistical planning was done by computer and, in an era before personal computers, a mainframe owned by Ian McNaught Davis' computer firm was used.[25]

Expedition team

The team was based on the climbers in the 1970 Annapurna and 1972 Southwest Face expeditions. Hamish MacInnes was to be deputy leader and Dougal Haston, Doug Scott, Mick Burke, Nick Estcourt, Mike Thompson and Martin Boysen agreed to take part. All except the last two had Southwest Face experience. A notable absentee was Don Whillans who was not invited because of personality clashes on the Annapurna expedition. People joining the team for the first time were Peter Boardman, Paul ("Tut") Braithwaite, Ronnie Richards, Dave Clarke, Allen Fyffe and Mike Rhodes. Rhodes was a Barclays employee, nominated by the bank. The doctors, both experienced mountaineers, were Charles Clarke and Jim Duff. Camp managers were Adrian Gordon and Mike Cheney who both spoke Nepali. There was to be a team of thirty-three climbing Sherpas with Pertemba as sirdar and Ang Phu as deputy. Twenty-six porters for the Khumbu Icefall were led by their sirdar Phurkipa. There were further Sherpas for general duties.[26][27]

In addition there was a liaison officer, Mohan Pratap Gurung, a four people from the BBC to make a television documentary – Christopher Ralling, Ned Kelly, Ian Stuart and Arthur Chesterman – and a Sunday Times reporter, Keith Richardson, all with their accompanying Sherpas. A team of drivers was needed for transport to Kathmandu.[28] In all there were nearly 100 people.[29]

Equipment

Twenty-four tonnes of equipment left Britain in over 1000 crates and needing to pass through 22 customs posts. Relatively little climbing gear was needed because the climb would be largely non-technical and rope, ladders and oxygen were the major requirements. Deadmen (anchors for embedding in snow) would be very useful because the conditions turned out to be those of soft snow.[30][31] Eleven tonnes of food was taken and a greater quantity was procured in Nepal. Meals of different menus were wrapped identically to avoid the risk of favourite meals being selected out before they could be carried high on the Face.[32] Face boxes (box-like tents), were needed because there are no sizeable ledges on the steep face. The face boxes used in 1973 had been found not strong enough to resist falling rocks and ice so for this expedition MacInnes designed small-size assault boxes for Camp 6, and strengthened boxes with roofs of bulletproof mesh for the lower camps on the face. The two-man assault boxes were 1.07 by 1.12 by 1.91 metres.[note 4][33]

The expedition

Two 16-tonne trucks, driven by Bob Stoodley (Transport Manager for the team) and three other drivers, left London on 9 April 1975 and the gear was driven to Kathmandu from where it was flown to Lukla Airstrip and then carried by porters to Khunde, near Namche Bazaar, where it arrived for storage on 10 June.[34] The climbers departed Britain on 29 July.[35]

Walk-in and Base Camp

The main team flew from London to Kathmandu from where they used landrovers as far as the end of the road at Lamosanghu (near Pagretar).[note 5] The walk-in from Kathmandu was a relaxed matter because no porter train was needed for the gear.[36] Two parties travelled separately a day or so apart so as not to place too much strain on the villages en route. By stopping for chang at each village, each day's walk was not too strenuous and so there was time to acclimatise. The weather was hot and humid (the monsoon was still on) and the first party took from 2 August until 18 August to reach Khunde and everyone had reached Base Camp by 23 August. The trek route runs west to east whereas all the rivers flow south so the journey involves crossing several ridges and descending into valleys.[37] The route is still used for trekking forty years later – although there is now a road that penetrates as far to the east as Jiri it does not reach all the way to Khumbu.[38] At Kharikola (near Jubing) the direction of travel changes to north up the valley of the Dudh Kosi river and it is here that the scenery changes as the valley becomes very deep with high mountains on both sides and the path starts to become steeper. At Thyangboche they met the lama to receive his blessing and then the whole ceremony was repeated outside for the benefit of the television cameras.[39]

Porters, most of them women, carried the baggage from Khunde past Lobuche and Gorak Shep to Base Camp and it was at this stage that one of the porters died. He was a young boy who had been on the 1972 expedition and who Doug Scott in particular had taken under his wing. He was deaf and dumb and when he went missing the search parties had no hope of hearing any calls for help. He was found dead in a stream just below Base Camp.[40]

Khumbu Icefall

Base Camp was established on 22 August and over the next few days more equipment and food were brought up there while a route was being reconnoitred through the Khumbu Icefall where the conditions in the ice seemed unusually benign.[41][42] The weather also was generally favourable with the cold mornings reducing the risk of ice seracs collapsing and dangerous avalanches. Generally snow would be falling in the afternoons and it could be heavy (18 inches (0.5 m) in an afternoon). With the monsoon not yet over there was a severe avalanche risk from Everest's West Ridge and Nuptse so a careful route had to be chosen between Base Camp and the Icefall. The original route taken by the lead climbers was changed when the highly experienced icefall sirdar, Phurkipa, considered it passed too close to the foot of the Lho La and the Western Shoulder.[41]

Work in the icefall would start in the very early hours of the morning as a route was roped along as safe a line as possible. Later in the day conditions would become so hot that that work had to stop not just for safety reasons but also because conditions became stifling. Ladders were placed over crevasses and additional ones had to be procured from Khunde as so many were being used.[note 6] Boysen had been delayed in his previous expedition and he joined the party during this time. On 28 August Camp 1 was set up at the top of the icefall and on that day sixty-eight people were moving through to consolidate the route and supply the camp. The camp was on a reasonably flat area of ice and surrounded by crevasses that would swallow the biggest avalanches in the vicinity. The ice block was inevitably slowly moving down the glacier and this would give problems later.[43]

Immediately above Camp 1 and before the Western Cwm proper, an immense crevasse stretched right across the valley. Under MacInnes' direction a 42-foot (13 m) ladder of 6-foot (1.8 m) sections was constructed, braced, and installed to bridge the gap. It was nicknamed Ballachulish Bridge after the bridge recently completed near MacInnes' home in Scotland.[44]

The Sunday Times correspondent was unwilling to show anyone his reports before dispatching them and the team became antagonistic towards him. Although Bonington publicly supported Richardson, Bonongton's own opinion was that the material could have been made available for comment while still letting the journalist have the final word. Just as this become a crisis Richardson developed pulmonary oedema on 29 August and he required emergency evacuation from Base Camp to Pheriche leading to the BBC's Ralling taking over the role of news reporter. In the case of the television journalism, a few aspects were agreed to be subject to veto by the climbers, in particular the use of Bonington's tape-recorded diary as a voice-over for the film, but rarely were the documentary makers not allowed to report what they wanted to.[45][46] Initially Scott and, especially, Haston had been disdainful that any film could give a true impression of climbing but as time went by a rapport with the television crew developed. Ralling and his colleagues were full members of the expedition and this gave potential problems over maintaining editorial independence although Ralling considered that in the event this worked out well.[46]

Western Cwm

It took three days for Haston and Scott to prospect a route to the head of the Western Cwm. The lower region was criss-crossed with crevasses, and was much more difficult than in 1972. It proved impossible to keep to the middle of the valley and they had to pass close to the foot of Nuptse. Despite the further supplies of ladders, there was still a shortage and so extra ones were salvaged from those abandoned by previous expeditions. On 31 August a site for Camp 2 was identified which was further up the cwm than in 1972 and, being on a slight hill, seemed safer from avalanches. It was at a shorter distance from the foot of the face and, indeed, a possible new route up the face presented itself starting beside the camp site itself and by-passing the previous expeditions' camps 3 and 4.[47]

With 150 loads dumped at Camp 1, Bonington moved his base there on 1 September with a view to going forward to inspect the location of Camp 2 and this was established as Advanced Base Camp (ABC) on 2 September at a height of 6,600 metres (21,700 ft).[48][49] Attracted by the newly proposed route up the face but uncertain of the right decision (the routes are shown in red on the diagram below), Bonington spent the night at ABC with Burke and Scott. Estcourt had not been at all in favour of the new line because it seemed likely to be in a path of avalanches. The following day brought poor visibility so the face could not be inspected and avalanches rumbled continuously. By 5 September a decision was taken against the new route after it had indeed been swept by quite major avalanches.[47]

Ascent of Southwest Face

From the bergschrund at the foot of the Southwest Face, the mountain slopes up at a steady angle of about 45°. Fixed ropes were to be set up from here for about a 1,700-metre (5,500 ft) vertical height, to not far below the South Summit. Camp 3 was at 7,000 metres (23,000 ft) as before.[50] The positioning of Camp 4 was reconsidered because it had in earlier years been in a very exposed location. Bonington had the idea of trying to find a safer location at a much lower height. Climbers from Advanced Base Camp had required two days to reach Camp 4 so they had always needed to sleep at Camp 3. On the other hand, the Sherpas could get straight from ABC to Camp 4 but they then needed the next day for rest. By lowering Camp 4 to about 7,300 metres (24,000 ft), Camp 3 could be mostly by-passed and the Sherpas could manage with one rest day in three. Everyone, most importantly Pertemba, supported the idea. Estcourt and Braithwaite had been making the route higher up the face and Braithwaite had commented on one particular place as being suitable for a camp although at the time they had considered it to be at too low an elevation. This eventually became the location selected and Camp 5 would be lowered to about 7,800 metres (25,500 ft). Bonington was left the considerable task of recalculating the logistics.[48][51]

When he was at last able to start true climbing, Boysen was moved to lyric poetry. He wrote "The morning was so magically beautiful, the Cwm swathed in boiling mists. Everest in dark blue shadow, Nuptse emerging diamond white, a hundred ice crests gleaming".[52]

MacInnes, Boardman and Boysen established Camp 4 on 11 September.[note 7] Even on the face the heat in the afternoon could become oppressive, seriously reducing their rate of climb. From this point on they starting using oxygen when climbing the face. Avalanches swept Camp 4 and the Great Central Gully above – MacInnes was struck and, although he was not swept away or buried, snow powder entered his lungs which was to have a lasting effect.[54]

On 14 September MacInnes had to descend to ABC when a start was made towards Camp 5. Haston tried to find a site suitable for a camp on the left side of the central gully but the area seemed it might be in an avalanche zone. Instead he found a location on the right-hand side protected by some ledges.[note 8] When Haston was alone at Camp 4 a night-time avalanche struck and the vacant box tent was seriously damaged. However, its structure had been so strong that Bonington thought that anyone inside would have survived.[56]

Bonington had to decide who should make the route to Camp 5, just below the Rock Band. He wanted to save the strongest climbers for scaling the Rock Band and for the summit attempt. MacInnes was incapacitated and Fyffe had not acclimatised well. Bonington had intended to always stay one camp down from the lead to be able to keep an overview without getting tangled in tactical decisions but in spite of this he decided he himself would go in front to Camp 5 with Richards in support. Sherpas would stay at Camp 4 for four days at a time while making three carries and would then return to ABC for two days' rest.[57] On 17 September Bonington, Richards and a team of Sherpas occupied Camp 5 which eventually had four box tents. After the Sherpas had set off down Bonington discovered he had left behind the cooking pan and his radio had stopped transmitting. They could only use a corned-beef tin to melt snow for cooking and drinking and this only produced tiny quantities of water. They were completely unable to summon help or provide leadership. After a few hours Richards found a workround for the transmitter problem and the next day they climbed up towards the Rock Band, still without adequate water. At this height Sherpas still did not need oxygen but two climbers together were needing three bottles a day, two for climbing and one for sleeping. Bonington led towards the left-hand gully but he had to backtrack after initially choosing a poor line. Next day Scott and Burke joined them at Camp 5 and the four started fixing ropes so that on 19 September the route was consolidated to the foot of the Rock Band. Things were well ahead of schedule.[58][59]

Climbing the Rock Band

Braithwaite and Estcourt had ascended to Camp 5 where the supply situation was now adequate. With Bonington contemplating a summit attempt by Haston and Scott, he asked Haston to climb from ABC to Camp 5 over the next two days – Scott was already at 5. He asked Estcourt and Braithwaite to attempt the Rock Band, supported by Burke and himself. This would rule them out of the first summit attempt so he told them they would be in any second attempt. It was the Rock Band that had defeated all previous expeditions. It consists of almost vertical cliffs with little snow or ice whereas the lower part of the face is angled at 45 to 60 degrees and is generally snow-covered.[60]

The route across the Rock Band lay in a narrow gully and Estcourt and Braithwaite alternated in the lead with Burke and Bonington in support by carrying up rope for the line being fixed in place.[59][53] The snow was good for crampons and Estcourt described the climb as "Scottish Grade III" although that disregarded the difficulty of any climb at 8,200 metres (27,000 ft).[59][note 10] Both climbers' oxygen ran out as they were reaching a ramp that led off to the right from the gully. With Braithwaite exhaused, Estcourt led up the ramp which narrowed so that he was forced against the wall with thin snow hardly covering loose rock and nowhere suitable for a piton. Eventually he reached a place where he could jam in a precarious piton and he then scrambled another 6 metres (20 ft) to where he found a safe place to belay. Estcourt described it as "the hardest pitch I have ever led" but from there it was only a very short climb to the snowfield above the Rock Band.[62][63] Lord Hunt wrote –

But I think that all members of the party would concede (with the exception of the person I allude to) that the supreme example of climbing technique, applied with exceptional determination, was Nick Estcourt's superb lead, without the normal safeguards or oxygen at 27,000 feet, up the rickety outward-leaning ramp of snow-covered rubble which led from the gully in the Rock Band up to the Upper Snow Field. This must be one of the greatest leads in climbing history, comparable, at least in its psychological effect, with the original lead across the Hinterstösser Traverse or the exit gully above the Spider, on the North Face of the Eiger.

— John Hunt, "Foreword", Everest the Hard Way. 1976.[64]

Summit attempts

The original plan had been for one team to lay fixed rope above Camp 6 at the top of the Rock Band and for a second team to go for the summit. Bonington now decided it would be unreasonable to expect the first team to turn back so near the summit and so one team would do all the work even though this meant a very long summit climb after a heavy day laying ropes and a second night at Camp 6.[60] However, progress had been so good that two further summit teams might be possible and, with careful planning, these might comprise four climbers each rather than two. Bonington had promised a place for a Sherpa in any subsequent attempt. He selected (1) Haston and Scott, (2) Boardman, Boysen, Burke and Pertemba (who, to Bonington's satisfaction, nominated himself[65]) and (3) Ang Phurba, Bonington, Braithwaite and Estcourt. Estcourt and Braithwaite were to return temporarily to ABC, losing their second place in the "queue" for the summit, and contrary to what they had been promised earlier. Burke had been climbing slowly but Bonington considered that this could have been due to the weight of camera equipment and he realised the value of having filming high up on the mountain. Regarding his own place, Bonington himself had been at 7,800 metres (25,500 ft) and above for nearly a fortnight so as team doctor Clarke privately advised him not to continue higher. Bonington accepted this opinion and gave his place to Richards though he still cherished the hope he himself might be in a fourth summit bid. MacInnes had moved to Camp 1 because of reports that the platform of ice it was on was starting to slip down the Icefall. When he heard he was to be left out of the summit parties he left the expedition because there was nothing further for him to do but he assured Bonington he would tell the press he was leaving because of his injured lungs.[66][67][68]

Haston and Scott

Haston and Scott were supported by Thompson, Burke, Bonington, Ang Phurba and Pertemba as they set off on 22 September to set up Camp 6 at 8,320 metres (27,300 ft) just beyond the point reached previously. The support team returned to Camp 5 leaving Haston and Scott to excavate a place for their assault box. The following day, as Bonington dropped back to ABC, the pair fixed 460 metres (1,500 ft) of rope on the line of the traverse of the snowfield towards a gully leading up to the Southeast Ridge.[69][68][70] This proved difficult because soft snow lay on the rock and there was little ice for crampons to grip. When all the rope had been fixed they returned to Camp 6. With a tent sack (but no tent or sleeping bags), two oxygen cylinders each, three 50-metre (160 ft) ropes between them, a stove and other gear they set off at 03:30 the next morning.[69]

From Advanced Base Camp the BBC cameras and many of the expedition were able to watch progress. A large powder avalanche swept past the two climbers who were just visible to the naked eye as they traversed the upper snowfield. They vanished into the South Summit gully and at 15:00 momentarily reappeared on the South Summit itself. They disappeared over the ridge into China but occasional puffs of snow above the ridge showed the watchers that they were still climbing despite it being late afternoon. Then as the light faded the climbers themselves could just be seen still moving up the ridge. Bonington radioed to the second team to prepare to set out next morning – they would not know whether they were making a summit bid or a rescue attempt.[71]

It had been at dawn, just after they had got beyond the fixed rope, that Haston's oxygen had failed. They were able to clear a blockage of ice but it delayed them for an hour. The climbing route to the ridge at the South Summit was up a gully at times through chest-deep snow in avalanche conditions at an angle of 60° and with no possibility of belays. At a rock step in the gully they left a fixed rope and at last after 11½ hours they reached the South Summit where they started digging a snow cave and brewing tea while they thought about whether to bivouac.[69][72] "Tea" is merely to describe the time of day because there was no food and nothing to put into the warmed water. Haston tested the conditions on the ridge and they decided to seize their opportunity to go on.[73]

The Hillary Step was climbed and the pair reached the summit of Mount Everest at 18:00, 24 September 1975.[note 11] The wind had dropped and the setting sun sometimes broke through between the clouds. The view was magnificent and they tried to identify some of the mountains and glaciers out across Himalaya. After an hour, and with half an hour to go before dark, they set off down hoping they could reach Camp 6 in moonlight. They left nothing on the summit.[73][75]

By the South Summit the moon had not appeared, lightning was flickering and the wind was rising. The descent of the gully seemed too dangerous so they had to prepare to bivouac at the greatest height ever attempted, 8,760 metres (28,750 ft). By 21:00 they had enlarged the snow cave and, with their oxygen cylinders exhausted and the fuel in their stove used up by midnight, they spent a cold night (Scott estimated -50 °C[76]) moving their limbs continuously and rubbing each other to keep any warmth in their bodies. To save weight, Scott had left his down clothing at Camp 6. There could be no sleep because sleep would be fatal.[73][77] At the time the Guardian described it as being like "spending the night in a sheet sleeping-bag in a deep freeze, with the oxygen cut by two-thirds".[78] At 05:30 they continued their descent and by 09:00 on 25 September they were back to Camp 6 after thirty hours without food or sleep. They radioed down the news.[73] Neither man had suffered frostbite.[77] As well as being the first people to summit Everest by the Southwest Face, they were also the first Britons to reach the summit by any route.[note 12][80] For the time, it had been the fastest ever ascent of Everest, 33 days.[note 13][81] The second summit team arrived at Camp 6 to find them safe and well and by afternoon Haston and Scott had jumared down to Advanced Base Camp.[71]

Boardman, Boysen, Burke and Pertemba

Moving up to camp 6 Burke had been climbing slowly and was very late in arriving. Bonington had previously suggested that Burke should retreat to Advanced Base Camp when he himself had gone back down but Burke had refused, saying he was feeling well. He was working as an assistant cameraman for the BBC and his filming was very important for him as well as for the whole team. This time Bonington told Boysen he would order Burke down but when Burke eventually reached camp he was able to persuade Bonington to let him continue.[82] The following morning all four started the ascent but Boysen's oxygen set soon failed and he lost a crampon and so had to return to the camp. Boardman and Pertemba climbed strongly with Burke lagging far behind. The pair had reached the South Summit by 11:00 where Pertemba's oxygen blocked in the same way as had Haston's. Taking advantage of the fixed rope up the Hillary Step left two days earlier, they reached the summit of Everest at 13:10, 26 September. There was poor visibility in the wind-driven mist.[83][84][85]

The weather deteriorated further as Boardman and Pertemba descended and the visibility was getting worse. To their astonishment they encountered Burke, sitting in the snow, only a few hundred metres from the summit and above the Hillary Step.[86] They had been assuming he had rejoined Boysen at camp 6. He asked them to return to the summit for him to photograph them but, seeing their reluctance, said he would go by himself to take some photographs and do some filming from the top. After agreeing to wait for him at the South Summit they separated. After a wait of over 1½ hours at the South Summit in blizzard conditions the visibility was down to about 3.0 metres (10 ft) and it was getting dark so at 16:10 the pair started to descend the gully in the storm. They still had oxygen and they were fortunate to find the end of the fixed ropes in the dark.[87] At 19:30 they at last rejoined Boysen at Camp 6.[88] Boardman had frostbite and Pertemba, who had taken over half an hour to crawl the last 30 metres (100 ft), was snowblind. Mick Burke did not return.[89] Boysen got frostbite while trying to reduce the snow piling on the box tents during the 36 hours that they were stormbound before being able to descend to Camp 5.[[#cite_note-FOOTNOTEGillman1993pp._86–92,_excerpting_from_'"`UNIQ--templatestyles-0000007E-QINU`"'<cite_id="CITEREFBoardman1976"_class="citation_journal_cs1">Boardman,_Peter_(1976)._"All_the_winds_of_Asia"._''Mountain_Life''_(January_1976).</cite><span_title="ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%253Aofi%252Ffmt%253Akev%253Amtx%253Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Mountain+Life&rft.atitle=All+the+winds+of+Asia&rft.issue=January+1976&rft.date=1976&rft.aulast=Boardman&rft.aufirst=Peter&rfr_id=info%253Asid%252Fen.wikipedia.org%253A1975+British+Mount+Everest+Southwest+Face+expedition"_class="Z3988"></span>-103|[90]]]

Clearing the mountain

The storm had passed by 28 September and the third summit team were still at Camp 5. However, with powder avalanches coming down the face and with no hope of finding Burke, the expedition was called off.[91] Those at Camp 5 waited for Boysen, Boardman and Pertemba and then accompanied them down to Advanced Base Camp on the Western Cwm where they were interviewed by the BBC.[92][46] Two days earlier Camp 1 had been evacuated as it began to slide down the Icefall and on 27 September the people at Camp 4 had been ordered down because it was threatened by the huge amount of snow higher up the face. During the evacuation, Gordon, who had been on the face for the first time, had become stranded in the dark and a rescue needed to be mounted – Bonington and Rhodes located him at 22:00 and managed to return with him to ABC at midnight. Later that night an avalanche devastated the entire camp and, though no one was injured, the camp had to be abandoned.[92][note 14] The expedition was back to Base Camp by 30 September, to Kathmandu by 11 October, and to London on 17 October.[94]

Subsequent events

Mick Burke's body has not been found[note 15] but it is thought likely he did reach the summit.[96]

The expedition considerably exceeded its planned expenditure – £130,000 rather than £100,000. Barclays, the sponsors, owned several media rights including those to the book Bonington was to publish, Everest the Hard Way, which became a best-seller and so they were able to recover their entire expenditure.[97] With the publicity given to the expedition, Bonington, Haston and Scott became household names in Britain. Bonington was made a CBE and later went on to receive a knighthood.[23]

The BBC produced a 75-minute television documentary about the expedition – the producer, Christopher Ralling, has written about the experience.[46] Thirty years later the BBC produced a retrospective radio programme which included contributions from Bonington.[98]

Two years later Scott was proposing a lightweight expedition to The Ogre in the Karakoram which was to include Bonington (as a team member) and Haston. While it was being planned, news came through that Haston had been killed in an avalanche while skiing in the Alps. The expedition went ahead and in fact Scott and Bonington became the first people to reach the summit.[99] Estcourt was killed on the 1978 Bonington-led K2 West Ridge expedition.[100] Boardman died together with Joe Tasker on Bonington's 1982 Everest Northeast Ridge expedition.[101]

Pertemba set up his own very successful trekking agency in 1985 and also in that year teamed up again with Bonington on a Norwegian-led expedition which led to Bonington reaching the summit of Everest for his first and only time.[102]

The Southwest Face was climbed by a Slovak expedition in 1988 when four climbers reached the South Summit in alpine style with no supplementary oxygen. Jozef Just went on to reach the main summit on 17 October but on the descent they all disappeared in a strong storm after their last radio contact with the base saying they were on the way to the South Col. Their bodies were never found.[103] A South Korean expedition climbed the route in 1995. However, on either side of the face (and so possibly to be included in its scope) are the South Pillar and Central Pillar[note 16] and these have been successfully used as climbing routes several times starting in 1980 and 1982 for the two routes respectively.[105]

In 1980 there was an ascent of Everest by a full North Face route; a Kangshung Face route was achieved in 1983.[106][104]

Notes

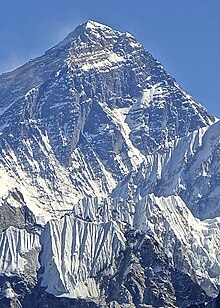

- ^ This photo was taken in November 2012 but photographs are available online showing the rather similar snow conditions during the expedition.[1]

- ^ On the Eiger climb Bonington and Burke were climbing journalist and cameraman.[2]

- ^ On the Old Man of Hoy climb MacInnes was climbing cameraman.[3]

- ^ Assault box size: 3 ft 6 in x 3 ft 8 in x 6 ft 3 in.

- ^ This road is now the Araniko Highway and it goes on further north to cross into China at the Sino-Nepal Friendship Bridge at Kodari.

- ^ It is a climbing convention that ladders are fully acceptable in these sorts of circumstances but they are never used on rock faces themselves.

- ^ The box tents at Camp 4 were still standing ten years later.[53]

- ^ Photographs show the face sloping at about 60° with no sign of ledges.[55]

- ^ Photographs are available online showing the rather similar snow conditions during the expedition.[1]

- ^ Scottish Grade III is similar to Alpine AD and has been described as "More sustained and steeper routes, generally following gullies or buttress (ridge) lines. Two axes required to overcome short, steep technical sections of ice or rock."[61]

- ^ Some of Scott's photographs are accessible online.[74]

- ^ Twenty-two years earlier the British press had treated Hillary and even Tenzing as if they were British. In the News Chronicle's front page story on 2 June 1953 the first paragraph was "Glorious Coronation Day news! Everest – Everest the unconquerable – has been conquered. And conquered by men of British blood and breed".[79]

- ^ 33 days measured from leaving Base Camp to reaching the summit. In 1979 this time was improved by a Swabian (Germany) team on the South Col route.

- ^ The trailer for the television documentary shows the final devastation at Advanced Base Camp.[93]

- ^ Not found as of April 2010.[95]

- ^ The South Pillar is also called the South Buttress and the Central Pillar is also called the Southwest Pillar.[104]

References

Citations

- ^ a b Boardman & Richards (1976), plates 1–6.

- ^ Thompson (2010), p. 246.

- ^ Thompson (2010), p. 231.

- ^ a b Thompson (2010), Chapter 6. 1939–1970: Hard Men in an Affluent Society, pp. 189–260.

- ^ a b Unsworth (2000), pp. 433–436.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), p. 434.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 436–442.

- ^ Bonington (1976), p. 18.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 442–443.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 585–593.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 266–269, 594.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), p. 594.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), p. 595.

- ^ a b Unsworth (2000), p. 596.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), p. 597.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), p. 442.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), p. 443.

- ^ Bonington (1986), p. 33.

- ^ Thompson (2010), p. 302.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 443–445, 448–449.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 170, 196.

- ^ Bonington (1976), p. 40.

- ^ a b Thompson (2010), p. 300.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 443–445.

- ^ Bonington (1986), pp. 34–35.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), p. 437, 447.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 39–43, 67.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), p. 447.

- ^ Bonington (1986), p. 48.

- ^ Bonington (1976), Richards, Ronnie & Stoodley, Bob. "Appendix 4, Transport" pp. 181–183.

- ^ Bonington (1976), Clarke, Dave. "Appendix 5, Equipment" pp. 184–197.

- ^ Bonington (1976), Thompson, Mike. "Appendix 7, Food" pp. 213–218.

- ^ Bonington (1976), MacInnes, Hamish. "Appendix 5, Equipment, Tentage" pp. 197–203.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 447–448.

- ^ Bonington (1986), p. 35.

- ^ Bonington (1986), p. 36.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 45–66, 158–159.

- ^ Kohli, Mohan Singh (2000). The Himalayas : playground of the gods : trekking, climbing, adventure. New Delhi: Indus Publishing Co. pp. 126–140. ISBN 9788173871078. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 45–66.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b Bonington (1976), pp. 62–68.

- ^ Boardman & Richards (1976), p. 3.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 67–75.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 75–82.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 76–78.

- ^ a b c d Ralling (1994).

- ^ a b Bonington (1976), pp. 83–89.

- ^ a b Unsworth (2000), p. 449.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 80–82.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 88, 90.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 91–95.

- ^ Bonington (1976), p. 98.

- ^ a b Bonington (1986), p. 39.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 98–103.

- ^ Bonington (1976), facing p. 104.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 103–108.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 107–109.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 104–116.

- ^ a b c Unsworth (2000), pp. 448–451.

- ^ a b Bonington (1976), pp. 117–119.

- ^ "Climbing Grades, Scottish Winter Grades". Elite Mountain Guides. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Unsworth (2000), p. 451.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 120–123.

- ^ Bonington (1976), Hunt, John. "Foreword" pp. 11–14.

- ^ Bonington (1986), p. 43.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 124–127.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 451–452.

- ^ a b Bonington (1986), p. 44.

- ^ a b c Unsworth (2000), pp. 452–453.

- ^ Boardman & Richards (1976), p. 9.

- ^ a b Boardman & Richards (1976), p. 11.

- ^ Bonington & Scott (1976), pp. 345–357.

- ^ a b c d Scott (1976).

- ^ "In Pictures: Doug Scott on Everest". On This Day. BBC. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gee, Christine; Weare, Garry; Gee, Margaret, eds. (2003). "Doug Scott". Everest : reflections from the top. London: Rider. ISBN 978-1844130528. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "1975: The Everest apprentice". Witness: On this Day 24 September. BBC. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Unsworth (2000), pp. 453–454.

- ^ Wilson, Ken (26 September 1975). "Everest beaten – the hard way". Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gillman (1993), p 64 shows a photo of the front page..

- ^ Thompson (2010), pp. 253, 299.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 465, 604.

- ^ Bonington (1986), pp. 46–47.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 454–455.

- ^ Gillman (1993), Eguskitza, Xavier. "Everest – the first forty years", p. 191.

- ^ Bonington (1976), p. 144.

- ^ Bonington (1986), p. 47.

- ^ Bonington (1976), p. 145.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 455–458.

- ^ Bonington (1976), pp. 14, 146–148.

- [[#cite_ref-FOOTNOTEGillman1993pp._86–92,_excerpting_from_'"`UNIQ--templatestyles-0000007E-QINU`"'<cite_id="CITEREFBoardman1976"_class="citation_journal_cs1">Boardman,_Peter_(1976)._"All_the_winds_of_Asia"._''Mountain_Life''_(January_1976).</cite><span_title="ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%253Aofi%252Ffmt%253Akev%253Amtx%253Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Mountain+Life&rft.atitle=All+the+winds+of+Asia&rft.issue=January+1976&rft.date=1976&rft.aulast=Boardman&rft.aufirst=Peter&rfr_id=info%253Asid%252Fen.wikipedia.org%253A1975+British+Mount+Everest+Southwest+Face+expedition"_class="Z3988"></span>_103-0|^]] Gillman (1993), pp. 86–92, excerpting from Boardman, Peter (1976). "All the winds of Asia". Mountain Life (January 1976).

- ^ Bonington (1986), pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b Bonington (1976), pp. 147–151.

- ^ Ralling & Kelly (1975).

- ^ Bonington (1976), p. 161.

- ^ "Hunt on for Wigan adventurer's Everest remains". Wigan Today. Wigan Observer. 27 April 2010. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Unsworth (2000), p. 457.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), p. 445.

- ^ Venables (2005).

- ^ Bonington (1986), pp. 49–59.

- ^ Curran, Jim (2013). K2: The Story Of The Savage Mountain. Hachette. ISBN 9781444778359. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Bonington (1986), pp. 142–153.

- ^ Bonington (1986), pp. 205–245.

- ^ Vranka, Milan (13 October 2013). "Príbeh štyroch slovenských horolezcov, ktorí zmizli na Mount Evereste". Plus 7 dní. www.pluska.sk. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Gillman (1993), Gillman, Peter. "Everest – the thirteen routes", pp, 186–187.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 659, 676.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 479–480, 501.

Sources

- Boardman, Peter; Richards, Ronnie (1976). "British Everest expedition SW face 1975" (PDF). Alpine Journal. 81 (325): 3–14. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bonington, Chris (1976). Everest the Hard Way. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 0340208333.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bonington, Chris (1986). The Everest Years: a climber's life. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0340366907.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bonington, Christian; Scott, Doug (1976). "Everest Southwest face" (PDF). American Alpine Journal. 20 (2): 345–358. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gillman, Peter, ed. (1993). "Everest – the Thirteen Routes". Everest: the best writing and pictures from seventy years of human endeavour. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0316904899.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ralling, Chris (1994). "Filming on Everest" (PDF). Alpine Journal: 116–124. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ralling, Chris; Kelly, Ned (1975). Everest the Hard Way (video download trailer). BBC. Retrieved 5 October 2014 – via SteepEdge.

{{cite AV media}}: External link in|via=|ref=harv(help) - Scott, Doug (1976). "Everest South-west Face Climbed". Himalayan Journal. 34. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thompson, Simon (2010). Unjustifiable risk? : the story of British climbing. Milnthorpe: Cicerone. ISBN 9781852846275.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Unsworth, Walt (2000). Everest: The Mountaineering History. Seattle, WA, US: Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0898866704.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Venables, Stephen (2005). The British on Top of the World (audio). BBC. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

{{cite AV media}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Willis, Clint (2008). "Chapter 12". The boys of Everest : the tragic story of climbing's greatest generation. London: Robson. p. 238. ISBN 9781905798216. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

See also

External links

- Trail magazine video of interview with Doug Scott (includes his commentary on 1975 expedition): Scott, Doug (23 July 2009). Doug Scott on Surviving Everest and The Ogre (video). Trail magazine. Retrieved 4 October 2014 – via YouTube.