Ibn Tumart

al-Imam al-Mahdi Muhamed Ibn Tumart | |

|---|---|

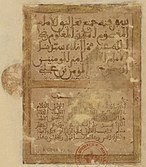

Coin minted during the reign of Abu Yaqub Yusuf, the last line of the inner inscription on the right reads: al-Mahdi Imam al-Umma[1] | |

| Title | Imam al-Umma إمام الأمة |

| Personal | |

| Born | 1080 Igiliz, Sous, Almoravid empire |

| Died | c. 1128–1130 |

| Resting place | Tinmel Mosque[10] |

| Religion | Islam |

| Nationality | Moroccan |

| Region | Maghreb Al Andalus |

| Jurisprudence | Zahiri |

| Creed | Ash'ari[2][3][4] Ash'ari-Mu'tazilite[5][6][7][8] |

| Movement | Almohad[5][9] |

| Muslim leader | |

| Disciple of | At-Turtushi |

Influenced by | |

Influenced | |

| History of Morocco |

|---|

|

Abu Abd Allah Muhammad Ibn Tumart (Berber: Amghar ibn Tumert, Arabic: أبو عبد الله محمد ابن تومرت, ca. 1080–1130 or 1128[11]) was a Moroccan Muslim Berber religious scholar, teacher and political leader, from the Sous region in southern Morocco. He founded and served as the spiritual and first military leader of the Almohad movement, a puritanical reform movement launched among the Masmuda Berbers of the Atlas Mountains. Ibn Tumart launched an open revolt against the ruling Almoravids during the 1120s. After his death his followers, the Almohads, went on to conquer much of North Africa and part of Spain.

Biography

Early life

Many of the details of Ibn Tumart's life were recorded by hagiographers, whose accounts probably mix legendary elements from the Almohad doctrine of their founding figure and spiritual leader.[12] Ibn Tumart was born sometime between 1078 and 1082 in the small village of Igiliz (exact location uncertain[13]) in the Sous region of southern Morocco.[14] He was a member of the Hargha, a Berber tribe of the Anti-Atlas range, part of the Masmuda (Berber: imesmuden) tribal confederation.[15][16] His father belonged to the Hargha and his mother to the Masakkala, both of which are divisions of the Masmuda tribal confederation.[15]

His name is given alternatively as Muhammad ibn Abdallah or Muhammad ibn Tumart. Al-Baydhaq reported that "Tumart" was actually his father Abdallah's nickname ("Tumart" or "Tunart" comes from the Berber language and means "good fortune", "delight" or "happiness", and makes it an equivalent of the Arabic name "Saad". As it was noted by Ahmed Toufiq in his research about Ibn al-Zayyat al-Tadili's famous book at-Tashawof, many early Sufi saints held this name in Morocco).[17][18] Ibn Khaldun reports that Muhammad ibn Tumart himself was very pious as a child, and that he was nicknamed Asafu (Berber for "firebrand" or "lover of light") for his habit of lighting candles at mosques.[19]

Ibn Tumart came from a humble family and his father was a lamp-lighter at the mosque.[20] By his own declaration and that of his followers, he claimed to be descendant of Idriss I, a descendant of Hassan, the grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, who took refuge in Morocco in the 8th-century.[21] However, and despite being supported by Ibn Khaldun, this ascendency is today largely disputed.[15] At the time, it was common for Berber leaders and tribes to claim a Sharif lineage in order to gain religious authority.[22]

Doctrines

At the time, Morocco, al-Andalus and large parts of Maghreb, were ruled by the Almoravids, a Maliki puritanical Saharan Sanhaja Berber movements, who founded the city of Marrakesh and are credited with spreading Islam to much of West Africa. To pursue his education, Ibn Tumart went as a young man (c. 1106) to Qortoba, which was at the time the biggest centre of learning in the Almoravids dominion, where he was a disciple of at-Turtushi. Thereafter, Ibn Tumart went east to deepen his studies where he came under the influence al-Ghazali's ideas (Almohad historians such as al-Marrakushi[23] support that he met and studied under al-Ghazali, but this contradicts what other historians like Ibn Khallikan have said, and modern historians also maintain that it is unknown whether this encounter actually happened).[24] He met and studied under both Mu'tazili and Ash'ari theologians.[5] De Lacy O'leary states that, in Baghdad, he attached himself to the Ash'arite school of theology and the Zahirite school of jurisprudence, but with the creed of Ibn Hazm which differed significantly from early Zahirites in its rejection of Taqlid and reliance on reason.[4] However, Abdullah Yavuz, argues the following:

He composed his own sectarian identity by combining the Maliki and Zahiri fiqh view, the kalam of Ash'ariyya and Mu'tazila, the Shii imamate thought and Mandi belief, and some principles of Kharijism with his own experiences. His sectarian identity emerged as the result of a selective attitude. With the sectarian identity he composed, he gained a ground for presenting both his actionist personality and his political goals.

— Yavuz[5]

It was probably while in Baghdad that Ibn Tumart began to develop a system of his own by combining the teachings of his Ash'arite masters with parts of the doctrines of others, with a touch of Sufi mysticism imbibed from the great teacher al-Ghazali.[8] Almohad hagiographers report that Ibn Tumart was in al-Ghazali's presence when news arrived that the Almoravids had proscribed and publicly burned his recent great work, Ihya' Ulum al-Din, upon which al-Ghazali is said to have turned to Ibn Tumart and charged him, as a native of those lands, with the mission of setting the Almoravids right.[14]

Ibn Tumart's main principle was a rigid unitarianism (tawhid) which denied the existence of the attributes of God as incompatible with his unity and therefore a polytheistic idea.[8] Ibn Tumart represented a revolt against what he perceived as anthropomorphism in the Muslim orthodoxy, but he was a rigid predestinarian and a strict observer of the law. He laid the blame for the "theological flaws" of the nation upon the ruling dynasty of the Almoravids. Ibn Thumart strongly opposed their sponsorship of the Maliki school of jurisprudence, whom he accused of neglecting the Sunnah and Hadith (traditions and sayings of Muhammad and his companions) and relying too much on ijma (consensus of jurists) and other sources, an anathema to the stricter Zahirism favored by Ibn Tumart. Ibn Tumart condemned the subtle reasoning of Maliki scholars as "innovations" (bid‘ah), obscurantist, perverse and possibly heretical.[8] Ibn Tumart also blamed the Almoravid governance for the latitude he found in Maghrebi society, notably the public sale of wine and pork in the markets, something the Qur'an forbids. Another reform was the destruction or hiding of any type of religious art in mosques. His rule and the rule of the Almohads after were full of reforms that attempted to turn the area under his control into a place where his doctrines held sway.

Ibn Tumart's followers took up the name "al-Muwwahidun", meaning those who affirm the unity of God. Spanish authors wrote that down as "Almohades", by which "Almohads" entered other languages.

Return to the Maghreb

After his studies in Baghdad, Ibn Tumart is claimed in one account to have proceeded on pilgrimage to Mecca (hajj), but was so bubbling with the doctrines he had learnt and a one-minded zeal to 'correct' the mores of the people he came across that he quickly made a nuisance of himself and was expelled from the city.[25] He proceeded to Cairo, and thereon to Alexandria, where he took a ship back to the Maghreb in 1117/18. The journey was not without incident - Ibn Tumart took it upon himself to toss the ship's flasks of wine overboard and set about lecturing (or harassing) the sailors to ensure they adhered to correct prayer times and number of genuflections; in some reports, the sailors got fed up and threw Ibn Tumart overboard, only to find him still bobbing a half-day later and fished him back (he is also reported in different chronicles of having either caused or calmed a storm at sea).[26]

After touching at Tripoli, Ibn Tumart landed in Mahdia and proceed on to Tunis and then Bejaia, preaching a puritan, simplistic Islam along the way. Waving his puritan's staff among crowds of listeners, Ibn Tumart complained of the mixing of sexes in public, the production of wine and music, and the fashion of veiling men unveiling women (a custom among the Sanhaja Berbers of the Sahara Desert, that had spread to urban centers with the Almoravids). Setting himself up on the steps of mosques and schools, Ibn Tumart challenged everyone who came close to debate – unwary Maliki jurists and scholars frequently got an earful.

His antics and fiery preaching prompted fed-up authorities to hustle him along from town to town. After being expelled from Bejaia, Ibn Tumart set himself up c.1119 at an encampment in Mellala (a few miles south of the city), where he began receiving his first followers and adherents. Among these were al-Bashir (a scholar, who would become his chief strategist), Abd al-Mu'min (a Zenata Berber who would become his eventual successor) and Abu Bakr Muhammad al-Baydhaq (who would later write the Kitab al-Ansab, the chronicle of the Almohads.) It was at Mellala that Ibn Tumart and his close companions began forging a plan of political action.

In 1120, Ibn Tumart and his small band of followers headed west into Morocco. He stopped by Fez, the intellectual capital of Morocco, and engaged in polemical debates with the leading Malikite scholars of the city. Having exhausted them, the ulama of Fez decided they had enough and expelled him from the city. He proceeded south, hurried along from town to town like a vagabond (reportedly, he and his companions had to swim across the Bou Regreg, as they could not afford the ferry passage). Shortly after his arrival in Marrakesh, Ibn Tumart is said to have successfully sought out the Almoravid ruler Ali ibn Yusuf at a local mosque. In the famous encounter, when ordered to acknowledge the presence of the emir, Ibn Tumart reportedly replied "Where is the emir? I see only women here!" - an insulting reference to the tagelmust veil worn by the Almoravid ruling class.[27]

Charged with fomenting rebellion, Ibn Tumart defended himself before the emir and his leading advisors. Presenting himself as a mere scholar, a voice for reform, Ibn Tumart set about lecturing the emir and his leading advisors about the dangers of innovations and the centrality of the Sunnah. When the emir's own scholars reminded him the Almoravids too embraced puritanical ideals, and were committed to the Sunnah, Ibn Tumart pointed out that the Almoravids professed puritanism had been clouded and deviated by "obscurantists", drawing attention to the ample evidence of laxity and impiety that prevailed in their dominions. When countered that at least on points of doctrine, there was little difference between them, Ibn Tumart brought out more emphasis on his own peculiar doctrines on the tawhid and the attributes. After a lengthy examination, the Almoravid jurists of Marrakesh concluded Ibn Tumart, however learned, was blasphemous and dangerous, insinuating he was probably a Kharijite agitator, and recommended he should be executed or imprisoned. The Almoravid emir, however, decided to merely expel him from the city, after a flogging of fourteen lashes.[14]

Ibn Tumart proceeded to Aghmat and immediately resumed his old behavior - destroying every jug of wine in sight, haranguing passers-by for impious behavior or dress, engaging locals in controversial debate. The ulama of Aghmat complained to the emir, who changed his mind and decided to have Ibn Tumart arrested after all. He was saved by the timely intervention of Abu Ibrahim Ismail Ibn Yasallali al-Hazraji ("Ismail Igig"), a prominent chieftain of the Hazraja tribe of the Masmuda, who helped him escape the city. Ibn Tumart took the road towards the Sous valley, to hide among his own people, the Haghra.

Cave of Igiliz

Before the end of 1120, Ibn Tumart arrived at his home village of Igiliz in the Sous valley (exact location uncertain).[28] Almost immediately, Ibn Tumart set himself up in a nearby mountain cave (a conscious echo of the Muhammad's withdraw to the cave of Hira). His bizarre retreat, his ascetic lifestyle, probably combined with rumors of his being a faith healer and small miracle-worker, gave the local people the initial impression that he was a holy man with supernatural powers (a point de-emphasized by later hagiographers).[14] But he soon set about spreading his principal message of puritanical reform. He preached in vernacular Berber. His oratory skill and crowd-moving eloquence are frequently referred to in the chronicles.

Towards the end of Ramadan in late 1121, in a particularly moving sermon, Ibn Tumart reviewed his failure to persuade the Almoravids to reform by argument. After the sermon, having already claimed to be a descendant of Muhammad, Ibn Tumart suddenly 'revealed' himself as the true Mahdi, the expected divinely guided justicer. He was promptly recognized as such by his audience. This was effectively a declaration of war on the Almoravid state. For to reject or resist the Mahdi's interpretations was equivalent to resisting God, and thus punishable with death as apostasy.[14]

(Notions of mahdism were not unfamiliar in this part of Morocco - not long before, the Sous valley had been a hotbed of Waqafite Shi'iism, a remnant of Fatimid influence, and descendance from Muhammad had been the principle recommendation of the fondly remembered Idrisids).

At some point he was visited by Abu Hafs Umar ibn Yahya al-Hintati ("Umar Hintati"), a prominent Hintata chieftain (and stem of the future Hafsids). Omar Hintati was immediately impressed and invited Ibn Tumart to take refuge among the Masmuda tribes of the High Atlas, where he would be better protected from the Almoravid authorities. In 1122, Ibn Tumart abandoned his cave and climbed up the High Atlas.[14]

In later years, Ibn Tumart's path from the cave of Igiliz to mountain fort of Tinmel - another conscious echo of the Muhammad's life (the hijra from Mecca to Medina) - would become a popular pilgrimage route for the Almohad faithful. The cave itself was preserved as a shrine for many years, where apparently Almohad partisans, regardless of their origin or background, would ceremonially reject their past affiliations and be "adopted" into Ibn Tumart's Hargha tribe).[29]

Tinmel and the Almohad rebellion

Ibn Tumart urged his followers to arms in open revolt against the Almoravids, to fulfill the mission of purifying the Almoravid state. In 1122, or shortly thereafter (c. 1124[30]) he founded a ribat at Tinmel (or 'Tin Mal', meaning "(she who is) white"), in a small valley of the Nfis in the middle of the High Atlas. Tinmel was an impregnable fortified complex, which would serve both as spiritual center and military headquarters of the Almohad rebellion. It is during this period that he wrote a series of monographs on various doctrines for the instruction of his men. These disparate works were later collected and compiled in 1183–84, on the order of the Almohad caliph Yusuf ibn Abd al-Ma'mun (later translated in French in 1903, under the title Livre d'Ibn Toumert.)

Six principal Masmuda tribes adhered to the Almohad rebellion: Ibn Tumart's own Hargha tribe (from the Anti-Atlas) and the Ganfisa, the Gadmiwa, the Hintata, the Haskura and the Hazraja (roughly from west to east, along the High Atlas range).[31]

For the next eight years, the Almohad revolt was largely confined to an irresolute guerilla war through the ravines and peaks of the Atlas range. The principal damage done by the Almohads at this stage was the disruption of Almoravid tax-collection, and rendering insecure (or altogether impassable) the roads and mountain passes south of Marrakesh. The Sous valley, surrounded on three sides by Almohadist Masmuda mountaineers, was nearly cut off and isolated. Of more particular concern to the Almoravids was their threat to the Ourika and Tizi n'Tichka passes, that connected Marrakesh to the Draa valley on the other side of the High Atlas. These were the principal routes to the all-important city of Sijilmassa, gateway of the trans-Saharan trade, by which gold came from west Africa to Morocco. But the Almoravids were unable to send enough manpower through the narrow passes to dislodge the Almohad rebels from their easily defended mountain strongpoints. The Almoravid authorities reconciled themselves to setting up strongpoints to confine them (most famously the fortress of Tasghimout that protected the approach to Aghmat), while exploring alternative routes through more easterly passes.[14][32]

Ibn Tumart's closest companion and chief strategist, al-Bashir, took upon himself the role of political commissar, enforcing doctrinal discipline among the Masmuda tribesmen, often with a heavy head. This culminated in an infamous purge (tamyiz) conducted by al-Bashir in the winter of 1129–30, with mass executions of disloyal partisans, which has been characterized as a brief "reign of terror".[14][33]

Battle of al-Buhayra

In early 1130, the Almohads finally descended from the mountains for their first sizeable attack on the Almoravids in the lowlands. It was a disaster. Al-Bashir (others report Abd al-Mu'min[34]) led the Almohad armies first against Aghmat. They quickly defeated the Almoravid force that came out to meet them, and then chased their fleeing remnant back to Marrakesh. The Almohads set up a siege camp before Marrakesh, the first recorded siege of the Almoravid capital, whose walls had only recently been erected. The Almoravid emir Ali ibn Yusuf immediately called upon reinforcements from other parts of Morocco. After forty days of siege, in May (others date 14 April 1130[35]), heartened by news of the approach of a relief column from Sijilmassa, the Almoravids sallied from Marrakesh in force and crushed the Almohads in the bloody Battle of al-Buhayra (named after a large garden east of the city). The Almohads were routed, suffering huge human losses - 12,000 men from the Hargha alone. Al-Bashir and several other leading figures were killed in action.[36] If not for a sudden torrential rain that broke up the fighting and allowed the remnant to escape back to the mountains, the Almohads might have been finished off then and there.

In a bizarre and chilling footnote in the aftermath, it is said that Ibn Tumart returned to the battlefield at night with some of his followers, and ordered them to bury themselves in the field with a small straw to breathe by. Then, to invigorate the rest of the demoralized Almohads, he challenged those who doubted the righteousness of their cause, to go to the battlefield and ask the dead themselves if they were enjoying the blisses of heaven after falling in the fight for God's cause. When they heard the positive reply from the buried men, they were assuaged. To prevent the ruse from being revealed, it is said Ibn Thumart left them buried there, filling their straws so they would suffocate.[37]

Almohads after Ibn Tumart

Ibn Tumart died in August 1130, only a few months after the disastrous defeat at al-Buhayra.[14] That the Almohad movement did not immediately collapse by the combined blows of the crushing defeat and large losses at the walls of Marrakesh, and the deaths of not only their spiritual leader, but also their chief military commanders, is testament to the careful organization that Ibn Tumart had built up at Tinmel.

Ibn Tumart had set up the Almohad commune as a minutely detailed pyramidical hierarchy with fourteen grades. At the top was the Ahl ad-Dar (the Mahdi's family), supplemented by a privy council known as the Council of Ten (Ahl al-jamāʿā) which included the Ifriqiyan migrants who had first joined Ibn Tumart in Mellala. There was also a wider consultative "Council of Fifty", composed of the sheikhs of the major Masmuda Berber tribes - the Hargha (Ibn Tumart's tribe, which had primacy in the hierarchy among the tribes), the Ganfisa, the Gadmiwa, the Hintata, the Haskura and the Hazraja.[14] The Almohad military had been organized as arranged "units" named by tribe, with sub-units and internal hierarchies carefully and exactly spelled out. There were also organized groups of Talba and Huffaz, the preachers that had been the original missionaries and spreaders of Ibn Tumart's message.

The Council of Ten

Ibn Tumart organized the inner 'Council of Ten' (Ahl al-jamāʿā), composed of the ten who had first borne witness to Ibn Tumart as Mahdi. Several of them were drawn from the core of followers that Ibn Tumart had picked up in Ifriqiya (esp. while holding camp at Mallala, outside of Bejaia, in 1119-20); others were local leaders drawn from the local Masmuda Berbers who had proven early adherents. Although the list has some variations and there is some dispute in names, the Council of Ten is frequently identified as follows:[38]

| Name | Notes |

|---|---|

| Abd al-Mu'min ibn Ali | originally from Tagra (near Tlemcen, modern Algeria), Abd al-Mu'min was a Berber of the Kumiya tribe of the Zenata confederation.[39] Abd al-Mu'min adhered at Mellala, and was given the appellation of "Lamp of the Almohads" (Siraj al-Muwahhidin). He became Almohad emir and the first Almohad caliph after Ibn Tumart's death in 1130. |

| Omar ibn Ali al-Sanhaji (known as "Omar Asanag") | a Sanhaja Berber, prob. adhered at Mellala Died c. 1142 of natural causes. Sometimes said to be the brother of the Almohad chronicler al-Baydhaq. |

| Abu al-Rabi' Sulayman ibn Makhluf al-Hadrami (known as "Ibn al-Baqqal") | from the people of Aghmat. His name was Arabized, he was known to the Berbers as bn al-Baqqāl and Ibn Tāʿḍamiyīt.

Killed at battle of al-Buhayra in 1130. |

| Abu Ibrahim Ismail Ibn Yasallali al-Hazraji (known as "Ismail Igig" or "Ismail al-Hazraji") | chieftain of Hazraja tribe of the Masmuda, who spirited Ibn Tumart from Aghmat to the High Atlas in 1120. Later appointed to lead Ibn Tumart's own Hargha tribe. |

| Abu 'Imran Musa ibn Tammara al-Gadmiwi | chieftain of the Gadmiwa tribe of the Masmuda of the High Atlas. Killed at 1130 battle of al-Buhayra |

| Abu Yahya Abu Bakr ibn Yiggit | from the Hintata tribe. He was killed in the 1130 battle of al-Buhayra. His son would briefly serve as Almohad governor of Cordova. |

| Abu Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Sulaīman | originally from the Massakala tribe. He came from Ānsā, an oasis in south of the Anti-Atlas. |

| Abd Allah ibn Ya'la (known as "Ibn Malwiya") |

prob. adhered at Mellala, later appointed as sheikh of the Ganfisa tribe of the Masmuda. He disputed the succession with Abd al-Mu'min, but was defeated and executed in 1132. |

| Abd Allah ibn Muhsin al-Wansharisi (known as "al-Bashir") | A scholar from Oran, prob. adhered at Mellala. He became Ibn Tumart's early right-hand-man and chief strategist and enforcer. Known as "the Herald" (al-Bashir), he was killed in the 1130 battle of al-Buhayra. |

| Abu Hafs Umar ibn Yahya al-Hintati (known as "Omar Hintata" or "Omar Inti") | chieftain of the Hintata tribe of the Masmuda of the High Atlas. Omar Hintata became the father-in-law and principal ally of Abd al-Mu'min. A major military leader, he is the stem of the later Hafsid dynasty of Ifriqiya. |

Of the Council of Ten, five were killed at al-Buhayra in 1130, two died in subsequent years, and only three survived well into the height of the Almohad empire - Abd al-Mu'min, Omar Hintata and Ismail al-Hazraji.

Succession

The Almohad hagiographer al-Baydhaq claims that Ibn Tumart had already designated Abd al-Mu'min as his successor back in Bejaia. But it seems more probable (although passed over in the chronicles) that there was an intense power struggle for succession in the aftermath of Ibn Tumart's death.[14] With half the Council of Ten killed at al-Buhayra, Abd al-Mu'min laid claim as the "successor" of the Ibn Tumart (the term "caliph", as "successor" of the Mahdi emerged only later, in conscious imitation of the term's original use for the "successors" of the Muhammad.) Abd al-Mu'min's claim was challenged by Ibn Malwiya (another survivor of the Ten) as well as by the Ahl al-Dar (Ibn Tumart's brothers).

Exactly how Abd al-Mu'min imposed himself is uncertain. As a Zenata Berber, Abd al-Mu'min was an alien among the Masmuda. But that foreignness itself might have recommended him as a neutral choice to the Masmuda sheikhs, as it would avoid the appearance of favoritism towards any particular tribe. Nonetheless it is reported that the more easterly Masmuda tribes, the Haskura and the Harzaja, rejected Abd al-Mu'min's leadership and broke away from the Almohad coalition at this stage.[40] Abd al-Mu'min would have to force them back to the fold. (Ibn Khaldun reports (improbably) that Abd al-Ma'mun managed to conceal the death of Ibn Tumart for nearly two years, in order to gather allies and marry the daughter of Omar Hintati, who would become his principal ally.) His principal rival Ibn Malwiya was captured, condemned and executed by 1132, and Ibn Tumart's own family soon disappears from significance, their roles eclipsed by Abd al-Mu'min's own family, the future dynasty of Almohad caliphs. Whatever doubts lingered about Abd al-Mu'min's leadership certainly dissipated a decade later, when Abd al-Mu'min led the renewed Almohads down from the mountains on a seven-year campaign of conquest of Morocco, culminating in the fall of Marrakesh in 1147.

Notes

- ^ Full inscription in Arabic: بسم ااالله الرحمان الرحيم لا إله إلا الله محمد رسول الله المهدي إمام الأمة

- ^ Mukti, Mohd Fakhrudin Abdul. "The Background of Malay Kalam With Special Reference to the Issue of the Sifat of Allah." Jurnal Akidah & Pemikiran Islam 3.1 (2002): 1-32.

- ^ Aymes, Marc. "Kemal H. Karpat, ed., with Robert W. Zens, Ottoman Borderlands: Issues, Personalities, and Political Changes (Madison, Wisc.: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003). Pp. 347. $37.50 paper." International Journal of Middle East Studies 40.3 (2008): 493-495.

- ^ a b De Lacy O'leary, Arabic Thought and Its Place in History, p. 249. Courier Dover Publications, 1939. ISBN 9780486149554

- ^ a b c d YAVUZ, A. Ö. (2017) . "The Sectarian Identity of Ibn Tumart." CUMHURIYET ILAHIYAT DERGISI-CUMHURIYET THEOLOGY JOURNAL , vol.21, pp.2069-2101.

- ^ García, Sénén. "The Masmuda Berbers and Ibn Tumart: An Ethnographic Interpretation of the Rise of the Almohad Movement." Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies 18.1 (1990). "Ibn Tumart preached what he considered orthodox Islam, a symbiotic doctrine of analogical interpretalion of the Qur'an, Mu'tazili and 'Ash'ari teachings, and Shi'i dogmas, especially that of the infallible Mahdi."

- ^ WASIL, IBN, and B. SALIM JAMALAL-DIN. "IBN YūNUS, ALi IBN “ABD." Medieval Islamic Civilization: AK, index 1 (2006): 375.

- ^ a b c d Kojiro Nakamura, "Ibn Mada's Criticism of Arab Grammarians." Orient, v. 10, pp. 89–113. 1974

- ^ Fletcher, Madeleine. "The Almohad tawhid: Theology which relies on logic." Numen 38.1 (1991): 110-127.

- ^ his shrine was destroyed by a Marinid lieutenant

- ^ Ibn Khaldun, Abderahman (1377). تاريخ ابن خلدون: ديوان المبتدأ و الخبر في تاريخ العرب و البربر و من عاصرهم من ذوي الشأن الأكبر. Vol. 6. دار الفكر. p. 305.

- ^ A French translation of the relation of the Almohad hagiographer Mohammed al-Baydhaq, can be found in Lévi-Provençal (1928). A Spanish translation of the arguably most reliable Almohad chronicle al-Bayan al-Mughrib of Ibn Idhari al-Marrakushi, can be found in Huici Miranda (1951). Ibn Idhari was a principal source for the account, Kitab al-'Ibar, of Ibn Khaldun. Ibn Khallikan's entry on Ibn Tumart can be found in English translation in Biographical Dictionary, 1843 M. de Slane trans., Paris, vol. 3, p.205)

- ^ Fromherz (2005: p.177) identifies Igiliz (and Ibn Tumart's nearby cave) with the modern small village of Igli, some 30 km east of Taroudannt in the Sous valley

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k H. Kennedy (1996)

- ^ a b c Hopkins, J.F.P. "Ibn Tūmart". Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill Publishers. p. 958.

- ^ Kennedy, Hugh (2014). Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of Al-Andalus. Routledge. p. 197. ISBN 9781317870418.

- ^ Ibn al-Zayyat al-Tadili; Ahmed Toufiq (1997) [1220]. at-Tashawof.

- ^ Encyclopaedia of the Orient - Ibn Tumart

- ^ Dramani Issifou (1988) "Islam as a social system in Africa since the seventh century", in M. Elfasi, editor, General History of Africa, Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century, ch.4, p. 99

- ^ History of Ibn Khaldun

- ^ For an attempt to trace this professed Sharifian lineage, see Ibn Khallikan's entry.

- ^ Even today the claim of Shariffian lineage of Morocco's current ruling dynasty, the Alaouites, is largely disputed

- ^ Cornell, Vincent J. "Understanding is the mother of ability: Responsibility and action in the Doctrine of Ibn Tūmart." Studia Islamica (1987): 71-103.

- ^ Julian, p. 93; Ibn Khallikan, p.206;

- ^ Ibn Khallikan, p. 206

- ^ Wasserstein (2003)

- ^ Messier (2010: p. 141)

- ^ See Fromherz (2005).

- ^ Fromherz (2005: p. 181)

- ^ Messier (2010:148)

- ^ Julien, p.99

- ^ Messier, 2010: p.153-54)

- ^ Messier (2010: p. 149) reports 15,000 men of Tinmel area were killed, and their wives and belongings distributed among the Almohad warriors.

- ^ Messier (2010: pp. 150–51)

- ^ Messier (2010: p. 151)

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam, p.592

- ^ James Edward Budgett-Meakin, (1899) The Moorish Empire: a historical epitome, London: Sonnenschein, p.69

- ^ Fromherz, Allen J. (2012). The Almohads: The Rise of an Islamic Empire. I.B.Tauris. pp. 123–124. ISBN 9781780764054.

- ^ Julien, p.93

- ^ Messier (2010: p. 153)

Bibliography

Written by Ibn Tumart

- (in Arabic) Le livre de Mohammed Ibn Toumert, mahdi des Almohades, 1903 edition, Ignác Goldziher, editor, Algiers: P. Fontana. full text online; introduction (Fr)

- (in Arabic and French) Évariste Lévi-Provençal (1928), editor, Documents inédits d'histoire almohade: fragments manuscrits du "Legajo" 1919 du fonds arabe de l'Escurial. Paris: Geuthner.

Written about Ibn Tumart

- (in French) Bourouiba, Rachid (1966) "A propos de la date de naissance d’Ibn Tumart", Revue d'Histoire et de Civilisation du Maghreb, January, pp. 19– 25.

- Cornell, Vincent J. (1987) "Understanding Is the Mother of Ability: Responsibility and action in the doctrine of Ibn Tumart", Studia Islamica, No. 66 (1987), pp. 71–103, JSTOR: [1]

- Cushing, Dana (2016) "Ibn Tumart" in: Curta and Holt, eds. Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History

- Fletcher, Madelaine (1991) "The Almohad Tawhid: Theology which relies on logic", Numen, Volume 38, Number 1, 1991, pp. 110–127. [2]

- Fromherz, Allen J. (2005) "The Almohad Mecca: locating Igli and the cave of Ibn Tumart", Al-Qantara, ISSN 0211-3589, vol. 26, no1, pp. 175–190

- García, Senén A. (1990) "The Masmuda Berbers and Ibn Tumart : an ethnographic interpretation of the rise of the Almohad movement" in Ufahamu, ISSN 0041-5715, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 3–24

- (in Spanish) Huici, Miranda, A. (1953–54, 1963) Colección de crónicas árabes de la Reconquista, 3 vols, Tetouan. Editora Marroqui.

- (in Spanish) Huici, Miranda, A. (1956–57) Historia politica delimperio Almohade, 2 vols., Tetouan. Editora Marroqui.

- Ibn Khallikan, Biographical Dictionary, 1843 M. de Slane trans., Paris, vol. 3, p.205)

- (in French) Julien, Charles-André (1931), Histoire de l'Afrique du Nord, des origines à 1830, 1961 ed., Paris: Payot.

- Kennedy, Hugh (1996) Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of al-Andalus. London: Addison-Wesley-Longman

- Laoust, H., "Une fetwā d’Ibn Taimīya sur Ibn Tūmart", in "Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, LIX" (Cairo, 1960), pp. 158–184.

- Messier, R.A. (2010) Almoravids and the Meanings of Jihad Santa Barbara, Calif.: Praeger.

- (in French) Millet, René (1923) Les Almohades: Histoire d'une dynastie berbère. Paris:, Soc. d'éditions géographiques.

- Wasserstein, D.J. (2003) "A Jonah theme in the biography of Ibn Tumart", in F. Daftary and J.W. Meri, editors, Culture and Memory in Medieval Islam: Essays in honour of Wilfred Madelung. New York: I.B. Tauris. pp. 232–49.

External links

- Biography on 'Muslim philosophy': [3]

- Comparative notes (in English) on sources of Moroccan history by French historian Lagadère.

- Profile on Ibn Tumart at Dar-Sirr.com

- 1080s births

- 1130 deaths

- Moroccan writers

- Berber rulers

- Berber Moroccans

- People from the Almohad Caliphate

- Moroccan Islamic religious leaders

- Moroccan scholars

- People from Tinmel

- People from Souss-Massa

- 12th-century Moroccan people

- 11th-century Moroccan people

- Moroccan religious leaders

- Zahiris

- Asharis

- Mahdiism

- 11th-century Berber people

- 12th-century Berber people

- Berber scholars

- Berber writers

- Masmuda

- Self-declared mahdi