Alexander Nevsky (Prokofiev)

Alexander Nevsky (Template:Lang-ru) is the score composed by Sergei Prokofiev for Sergei Eisenstein's 1938 film Alexander Nevsky. The subject of the film is the 13th century incursion of the knights of the Livonian Order into the territory of the Novgorod Republic, their capture of the city of Pskov, the summoning of Prince Alexander Nevsky to the defense of Rus', and his subsequent victory over the crusaders in 1242. The majority of the score's song texts were written by the poet Vladimir Lugovskoy.

In 1939, Prokofiev arranged the music of the film score as the cantata, Alexander Nevsky, Op. 78, for mezzo-soprano, chorus, and orchestra. It is one of the few examples (Lieutenant Kijé is another) of film music that has found a permanent place in the standard repertoire, and has also remained one of the most renowned cantatas of the 20th century.

Eisenstein, Prokofiev, and Lugovskoy later collaborated again on another historical epic, Ivan the Terrible Part 1 (1944) and Part 2 (1946, Eisenstein's last film).

Alexander Nevsky, film score (1938)

Composition history

The score was Prokofiev's third for a film, following Lieutenant Kijé (1934) and The Queen of Spades (1936).[1] Prokofiev was heavily involved not just with the composition, but with the recording as well. He experimented with different microphone distances in order to achieve the desired sound. Horns meant to represent the Teutonic Knights, for instance, were played close enough to the microphones to produce a crackling, distorted sound. The brass and choral groups were recorded in different studios and the separate pieces were later mixed.[2]

Prokofiev employed different sections of the orchestra, as well as different compositional styles, to evoke the necessary imagery. For instance, the Teutonic Knights (seen as the adversary) are represented by heavy brass instruments, playing discordant notes in a martial style. The sympathetic Russian forces are represented predominantly by folk-like instruments such as woodwind and strings,[3] often playing quasi-folksong style music.

Publication history

In 2003, German conductor Frank Strobel reconstructed the original score of Alexander Nevsky with the cooperation of the Glinka State Central Museum of Musical Culture and the Russian State Archive of Literature and Art (RGALI). The score is published by Musikverlage Hans Sikorski, Hamburg.

Performance history

The film Alexander Nevsky premiered on 23 November 1938 at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow.[4]

The concert premiere of the complete original film score, as reconstructed by Frank Strobel, took place on 16 October 2003, accompanied by a showing of the film at the Konzerthaus Berlin. Strobel conducted the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Ernst Senff Chor, with mezzo-soprano Marina Domashenko as soloist.[4]

The Russian premiere of the restored film score took place on 27 November 2004 at the Bolshoy Theatre.

Instrumentation

- Strings: violins I & II, violas, cellos, double basses

- Woodwinds: piccolo, 2 flutes, 3 oboes (including English horn), 3 clarinets (including E-flat clarinet), 2 bass clarinets, 2 alto saxophones, 2 tenor saxophones, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon)

- Brass: 4 horns, 5 trumpets (including cornet), 3 trombones, bass trombone, 2 tubas

- Percussion: timpani, 2 snare drums, bass drum, cymbals, 2 tambourines, wood block, rattle, triangle, xylophone, tubular bells, tamtam, gong

- Other: 2 harps, piano

- Banda: 2 horns, tierhorn, 2 trumpets, tenor flügelhorn

Cues

Film score cues are musical numbers, background music, music fragments (e.g., fanfares), musical soundscape (e.g., bells), or strings of these, forming continuous stretches of music with little or no intervening dialogue. The finished soundtrack of Alexander Nevsky contains 27 cues.[4] The original working titles of the cues in Prokofiev's manuscripts are listed in the table below. The list appears to be incomplete, and the titles themselves are not particularly descriptive.

The first column represents the cue numbers to which the titles likely correspond. The original Russian titles are provided by Kevin Bartig in Composing for the Red Screen, where they are not numbered, but are grouped by thematic content.

The fourth and fifth columns give the German titles and their sequence as provided by Musikverlage Hans Sikorski [1], the publisher of the restored original film score. This order of the cues does not appear to represent the sequence used in the film.

The table can be sorted by clicking on the buttons in the title bar. The default sequence can be restored by refreshing the browser (press F5).

| Original | English | German | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Разоренная Русь | Ravaged Rus' | Das zerstörte Russland | 01 |

| 02 03 |

«А, и было дело на Неве-реке» | "It happened on the Neva River" | ||

| 05 | Псков 1-й | Pskov 1 | Pskow (Das erste) | 03 |

| 06 | Псков 2-й | Pskov 2 | Pskow (Das zweite) | 04 |

| 07 | «Вставайте, люди русские!» | "Аrise, Russian People!" | ||

| 08 | Вече | Veche | Das Wetsche | 07 |

| 09 | Вече | Veche | Das Wetsche | 08 |

| 10 | Мобилизация | Mobilization | Mobilisierung | 09 |

| 12 | Рассвет | Dawn | Sonnenaufgang | 02 |

| 13? | Русские рожки | Russian Horns | Russische Hörner | 11 |

| 14 | Свинья | Swine (or The Wedge) | Das Schwein | 10 |

| 15 | Конная атака | Cavalry Attack | Reiterattacke | 19 |

| 16? | Рога перед каре | The Horns before the Square | Das Horn vor dem Karree | 13 |

| 16 | Каре | The Square | Das Karree | 15 |

| 17? | Рог тонет | The Horn Sounds | Das Horn geht unter | 12 |

| 18 | Поединок | The Duel | Der Zweikampf | 16 |

| 18? | После поединка | After the Duel | Nach dem Zweikampf | 17 |

| 19? | Рога в преследовании | The Horns in the Pursuit | Das Horn in der Verfolgung | 18 |

| 19 | Преследование | The Pursuit | Verfolgung | 20 |

| 20 21 |

«Отзовитеся, ясны соколы» | "Respond, bright falcons!" | ||

| 22 | Въезд во Псков | Entry into Pskov | Einzug in Pskov | 21 |

| ? | Псков 3-й | Pskov 3 | Pskow (Das dritte) | 05 |

| ? | Псков 4-й | Pskov 4 | Pskow (Das vierte) | 06 |

| 26 | Сопели | Sopeli | Das Prusten | 14 |

| 27 | Finale | Finale | 22 |

Note: "Sopeli" (flutes or recorders) refers to two passages, one in 'The Battle on the Ice', cue 16, and one in the final scene in Pskov, cue 26, that depict a group of skomorokhi. The group appears to be composed of players of svireli (flutes), zhaleyki (hornpipes), rozhki (horns), bubnï (tambourines), and other folk or skomorokh instruments.

Structure

The film is divided into 9 'scenes' by intertitles stating the location of the action, or, in the case of the 'Battle on the Ice', the date—'5 April 1242'. The table below shows the scenes and cues with the musical numbers (or accompanying action) they contain:

Note: A gray background indicates numbers omitted in the cantata.

| Intertitle | Cue | Numbers and themes | Scoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| It was the 13th century... | Ravaged Rus' |

Rus' under the Mongol Yoke | Orchestra |

| Lake Pleshcheyevo | "It happened on the Neva River" |

Song about Alexander Nevsky | Chorus, orchestra |

| Chorus, orchestra | |||

| Lord Novgorod the Great | The Bells of Novgorod | Bells | |

| Pskov | Pskov |

The Crusaders in Pskov | Orchestra |

| He Who Died a Noble Death for Rus' | Orchestra | ||

| Horn Call of the Crusaders | Brass | ||

| "Peregrinus expectavi" | Chorus, orchestra | ||

| The Crusaders in Pskov | Orchestra | ||

| Horn Call of the Crusaders | Brass | ||

| He Who Died a Noble Death for Rus' | Orchestra | ||

| Pereyaslavl | "Arise, Russian People!" |

"Arise, Russian People!" | Chorus, orchestra |

| Novgorod | Veche |

In Our Native Rus' | Orchestra |

| Orchestra | |||

Mobilization |

"Arise, Russian People!" | Chorus, orchestra | |

| Lake Chudskoye | The Crusaders' Camp ("Peregrinus expectavi") |

Chorus, orchestra | |

Dawn |

Alexander Nevsky's Camp (Rus' under the Mongol Yoke) |

Orchestra | |

| Fanfares | Brass | ||

| 5 April 1242 | Swine |

Awaiting the Enemy at Raven's Rock | Orchestra |

| Horn Call of the Crusaders | Brass | ||

| Charge of the Crusaders | Chorus, orchestra | ||

Cavalry Attack |

The Russian Counterattack | Orchestra | |

The Square |

The Skomorokhi | Orchestra | |

| Horn Call of the Crusaders | Brass | ||

| "Peregrinus expectavi" | Chorus, orchestra | ||

| Spears and Arrows | Orchestra | ||

| Fanfare | Brass | ||

The Duel |

Duel between Alexander and the Grand Master |

Orchestra | |

The Pursuit |

The Crusaders Routed | Orchestra | |

| The Ice Breaks | Percussion, orchestra | ||

"Answer, Bright Falcons!" |

The Field of the Dead | Soloist, orchestra | |

| Orchestra | |||

| Pskov | Entry into Pskov |

The Bells of Pskov | Bells |

| The Fallen | Orchestra | ||

| The Prisoners | Orchestra | ||

| Song about Alexander Nevsky | Orchestra | ||

| In Our Native Rus' | Orchestra | ||

| The Prisoners | Orchestra | ||

| Song about Alexander Nevsky | Orchestra | ||

| The Prisoners | Orchestra | ||

| The Fallen | Orchestra | ||

| "In Our Native Rus'" | Chorus, orchestra | ||

Sopeli |

The Skomorokhi | Orchestra | |

Finale |

Song about Alexander Nevsky | Orchestra |

The performance duration is approximately 55 minutes.[4]

Repeating themes

The following themes occur in two or more cues.

- 'Ravaged Rus'': 1, 12

- "It happened on the Neva River": 2, 3, 22, 27

- 'The Crusaders': 5, 6, 14, 16

- 'He Who Died a Noble Death for Rus'': 6, 20

- 'Horn Call of the Crusaders': 6, 14, 16, 19

- "Peregrinus expectavi": 6, 11, 14, 16

- "Arise, Russian people!": 7, 10

- "To the living fighter esteem and honor": 7, 10, 15, 19

- "In our native Rus'": 7, 8, 9, 10, 22, 25

- "The enemy shall not occupy Rus'": 7, 10, 15, 19

- 'Cavalry Attack': 15, 19

- 'Skomorokhi': 16, 26

- "I shall go over the white field": 20, 21, 22, 24

- 'The Prisoners': 22, 23

Alexander Nevsky, cantata, Op. 78 (1939)

Composition history

The great popularity of Eisenstein's film, which was released on 1 December 1938, may have prompted Prokofiev to create a concert version of the music in the winter of 1938–39. Prokofiev condensed the 27 film score cues into a seven movement cantata for mezzo-soprano, chorus, and orchestra, structured as follows:

| No. | Title | English | Scoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| Русь под игом монгольским | Rus' under the Mongol Yoke | Orchestra | |

| Песня об Александре Невском | Song about Alexander Nevsky | Chorus, orchestra | |

| Крестоносцы во Пскове | The Crusaders in Pskov | Chorus, orchestra | |

| Вставайте, люди русские! | Arise, Russian People! | Chorus, orchestra | |

| Ледовое побоище | Battle on the Ice | Chorus, orchestra | |

| Мёртвое поле | The Field of the Dead | Soloist, orchestra | |

| Въезд Александра во Псков | Alexander's Entry into Pskov | Chorus, orchestra |

The performance duration is approximately 40 minutes.[5]

There are many changes in the cantata. Prokofiev remarked to sound engineer Boris Volskiy: "Sometimes it is easier to write a whole new piece than solder one together."[6]

"Once the film made it to the screen I had the desire to rework the music for symphonic orchestra and chorus. To create a cantata out of the music wasn't easy; I ended up expending much more labor on it than the original film. I first needed to provide it with an exclusively musical foundation, arranged in accord with the logic of musical form, with purely symphonic development, and then completely reorchestrated—since scoring for orchestra is of an entirely different [order] than scoring for a film. Despite my effort this second time around to approach the music from an exclusively symphonic perspective, the pictorial element from Eisenstein's film obviously remained."[7] (22 March 1942)

Russian original«После того, как фильм появился на экране, у меня возникло желание использовать музыку для симфонического произведения с хором. Это была нелегкая работа, и для того, чтобы сделать из этой музыки кантату, мне пришлось затратить гораздо более трудов, чем при первоначальном сочинении ее для фильма. Прежде всего требовалось подвести под нее чисто музыкальные основания, построить согласно музыкальной формы, развить ее чисто симфонически, затем все наново переоркестровать, ибо оркестровка симфоническая совсем другого порядка, чем оркестровка для фильма. Несмотря на мое старание подходить к музыке во время этой второй моей работы с чисто симфонической точки зрения, в ней остался известный элемент живописности, идущий от фильма и Эйзенштейна.»

Although some 15 minutes of music from the film score are omitted, the cuts mainly consist of needless repetitions, fragments, soundscape, and a few instances of unmemorable music.

Omissions: The table above (under "Film score") shows the cues and numbers omitted from the cantata. There is no ad libitum bell tolling from the Novgorod and Pskov scenes. The 'Horn Call of the Crusaders' is no longer played as a free standing brass number, but is now combined with other themes as part of the orchestral texture. 'The Crusaders' Camp', being a repeat of the "Peregrinus expectavi" theme, is omitted. Two significant numbers featuring themes not presented elsewhere, 'Spears and Arrows' and all iterations of 'The Prisoners', are not included. Iterations of 'The Fallen' are omitted, perhaps because they are a restatement of the theme "I shall go over the white field" from 'The Field of the Dead'.

Abbreviations: About half the choral repetitions of stanzas of "Arise, Russian People!" are cut, as are all of the instrumental versions. The 'Charge of the Crusaders' is condensed, losing about half its length. The 'Duel' is greatly shortened (only the first 12 measures are preserved), and moved to an earlier position, alternating briefly with 'The Skomorokhi'.

Consolidation: Numbers broken into two cues by dialogue, such as 'Song about Alexander Nevsky' and 'The Field of the Dead', have their respective parts joined together. 'Rus' under the Mongol Yoke' now concludes with a repeat of the opening passage, possibly taken from 'Alexander Nevsky's Camp', giving the movement an ABA form.

Recomposition: 'The Ice Breaks', which depicts the crusaders perishing, consisting in the film score of percussive sound effects, is now replaced by a substantial section of new music (the Brohn version of the film score uses this and the new introduction to "Arise, Russian People!" as an opening credits prelude).

Expansion: The 'Finale' of the film score, rather perfunctorily performed by a modest studio orchestra without chorus, is, in the cantata, enlarged and transformed into a massive and glittering 'Final Chorus' with prominent brass and percussion section accompaniment.

Additions: The 'Song about Alexander Nevsky' gains a new third stanza ("Where the axe was swung, there was a street"). "Arise, Russian People!" gains a new introduction consisting of loud woodwind and brass chords, clanging bells, xylophone glissandi, and plucked strings. In 'The Battle on the Ice', there is now, after the 'Charge of the Crusaders', an added section depicting the commencement of fighting between the Livonian knights and the Russian defenders, with some additional Latin text ("Vincant arma crucifera! Hostis pereat!") 'The Battle on the Ice' now concludes with a quiet and poignant instrumental repeat of the "In our native Rus'" theme from "Arise, Russian People!". In 'The Field of the Dead', the first stanza, which is instrumental in the film score, now has an added vocal part ("I shall go over the white field") for the soloist. 'Alexander's Entry into Pskov' gains a new passage ("Rejoice, sing, mother Rus'!") depicting the people's celebration, with glockenspiel, xylophone, and harp accompaniment. Two more repetitions of "In our native Rus'" are added to 'Alexander's Entry into Pskov', one combined with the end of 'The Skomorokhi', and one following it, leading to the final stanza based on 'Song about Alexander Nevsky'.

Despite these many modifications, the order of events and music changes hardly at all, and the best music is not only preserved, but improved by larger instrumental forces, richer orchestration, added choral accompaniments, greater dynamic contrasts, and, obviously, greater continuity. Furthermore, in 'The Crusaders in Pskov', 'The Battle on the Ice', and 'Alexander's Entry into Pskov', Prokofiev indulges in more frequent juxtaposition and overlap of themes, resulting in greater rhythmic complexity and some jarring dissonances.

Publication history

- 1939, 'Three songs from the film Alexander Nevsky', Op. 78a, Muzgiz, Moscow; the numbers were:

- "Arise, Russian People"

- "Answer, Bright Falcons" ('The Field of the Dead')

- "It Happened on the Neva River" ('Song about Alexander Nevsky')[8]

- 1941, Alexander Nevsky, cantata for mezzo-soprano, mixed chorus, and orchestra, Op. 78, Muzgiz, Moscow

Performance history

The world premiere of the cantata took place on 17 May 1939. Sergei Prokofiev conducted the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra and Chorus in the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory, with soloist Varvara Gagarina (mezzo-soprano).[5]

The first American performance took place on 7 March 1943 in an NBC Radio broadcast. Leopold Stokowski conducted the NBC Symphony Orchestra and the Westminster Choir, with soloist Jennie Tourel (mezzo-soprano).[citation needed]

The American concert premiere took place on 23 March 1945, when Eugene Ormandy led the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Westminster Choir, with soloist Rosalind Nadell (contralto).[citation needed]

Instrumentation

- Strings: violins I & II, violas, cellos, double basses

- Woodwinds: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, tenor saxophone, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon

- Brass: 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba

- Percussion: timpani, snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, tambourine, maracas, wood block, triangle, tubular bells, tamtam, glockenspiel, xylophone

- Other: harp

Movements

- "Rus' under the Mongol Yoke": The opening movement begins slowly, and in C minor. It is meant to evoke an image of destruction, as brought to Rus' by the invading Mongols.

- "Song about Alexander Nevsky": This movement (B-flat) represents Prince Alexander Yaroslavich's victory over the Swedish army at the Battle of the Neva in 1240. Alexander received the name 'Nevsky' ("of the Neva") in tribute.

- "The Crusaders in Pskov": For this movement (C-sharp minor), Prokofiev's initial intention was to use genuine 13th century church music; however, the examples he found in the Moscow Conservatoire sounded so cold, dull and alien to the 20th century ear that he abandoned the idea and instead composed an original theme "better suited to our modern conception" to evoke the brutality of the Teutonic Knights.[9]

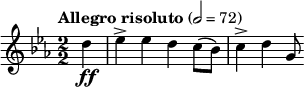

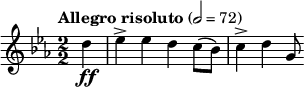

- "Arise, Russian People": This movement (E-flat) represents a call to arms for the people of Russia. It is composed with folk overtones.

- "The Battle on the Ice": The fifth (and longest) movement is arguably the climax of the cantata. It represents the final clash between Nevsky's forces and the Teutonic Knights on the frozen surface of Lake Peipus in 1242. The quietly ominous beginning (representing dawn on the day of battle) is contrasted by the jarring middle section, which is cacophonous in style.

- "The Field of the Dead": Composed in C minor, the sixth movement is the lament of a girl seeking her lost lover, as well as kissing the eyelids of all the dead. The vocal solo is performed by a mezzo-soprano.

- "Alexander's Entry into Pskov": The seventh and final movement (B-flat) echoes the second movement in parts, and recalls Alexander's triumphant return to Pskov.

Text analysis

The Latin text devised by Prokofiev for the Livonian knights appears at first sight to be random and meaningless:

- "Peregrinus expectavi, pedes meos in cymbalis"

- ("A pilgrim I waited, my feet in cymbals")

According to Prokofiev, "the Teutonic knights sing Catholic psalms as they march into battle."[9] In 1994, Dr. Morag G. Kerr, a soprano with the BBC Symphony Chorus, was the first to notice that the words are indeed from the Psalms, specifically from the Vulgate texts chosen by Igor Stravinsky for his 1930 Symphony of Psalms.[10] Dr. Kerr believes Prokofiev may have felt a temptation to put the words of his rival into the mouths of the one-dimensional Teutonic villains of Eisenstein's film.[11] This explanation has been accepted by the BBC: "Even their words are gibberish, with Prokofiev rather mischievously creating them by chopping up Latin texts from Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms and then randomly stringing them together".[12] In the 'Battle on the Ice', the Latin phrase Prokofiev concocted ends with 'est', which is not found in Symphony of Psalms, but is possibly a pun on the first letters of Stravinsky's surname in Latin characters (Prokofiev enjoyed such games).[13][dubious – discuss]

A motive for this nonsensical parody may be found in the lifelong rivalry between the two Russian composers, specifically in the younger man (Prokofiev's) dismissal of Stravinsky's idiom as backward-looking "pseudo-Bachism",[14] and his disdain for Stravinsky's choice to remain in western Europe, in contrast to Prokofiev's own return to Stalinist Russia in 1935.[dubious – discuss]

Versions by other hands

Film score reconstruction by William Brohn (1987)

Composition history

In 1987, orchestrator William Brohn created a version of Alexander Nevsky that could replace the widely derided original soundtrack in showings of the film accompanied by a live symphony orchestra. Producer John Goberman provides the following details concerning the genesis of the Brohn version:

"[Prokofiev] had orchestrated his score for a small recording studio orchestra, intending to achieve orchestral balances through miking techniques... However, partly because of Prokofiev's intent to experiment with the new soundstage recording techniques, the soundtrack for Alexander Nevsky is a disaster. Ironically, the best film score ever written is probably the worst soundtrack ever recorded. The intonation of the instruments and of the chorus is sad, and the frequency range is limited to 5,000 Herz (as opposed to an industry standard of 20,000 Hz). This in the period when Hollywood was turning out Gone with the Wind and Disney's Fantasia.

[...] In 1986, realizing that the Cantata contained virtually all the musical ideas of the film, I considered the possibility of overcoming the limitations of the original soundtrack by finding a way to perform this most monumental of all film scores with a full symphony orchestra and chorus accompanying the film in the concert hall. Crucial to the approach was that in the Cantata we had Prokofiev's own orchestration. If we could work out the technical issues, we could achieve a completely authentic re-creation of the film score which would allow audiences to hear what Prokofiev heard when he saw the magnificent images created by Eisenstein. I engaged the brilliant orchestrator (and my good friend) Bill Brohn to use the cantata to re-create the film score, both of us committed to the authenticity of the project from the beginning.

[...] So here, more than 50 years after the conception of Alexander Nevsky, we can witness the extraordinary visual imagination of Prokofiev captured in a soundtrack recording of what is probably the greatest film score ever written, in the authentic and unmistakable musical hand of its author."[15]

At the time the Brohn version was written, Prokofiev's original manuscripts of the film score were unavailable for study. Brohn transcribed the score, using the orchestration of the cantata as a model. Music not present in the cantata was transcribed by ear from the film. With special attention paid to tempos a 1993 recording of this version was matched to a new edition of the film, which was released in 1995.

Although the Brohn version is not technically the film score as composed by Prokofiev, it is a brilliantly successful substitute for the original soundtrack for live performances by a full symphony orchestra accompanying showings of the film. There is little in the arrangement that is not by Prokofiev. However, it is more accurate to say that this arrangement is a "hybrid" of the film score and the cantata, allowing the audience the opportunity to enjoy the film score cues using the expanded sound values of the cantata.

Performance history

The Brohn version premiered on 3 November 1987 at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles. André Previn conducted the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra and the Los Angeles Master Chorale, with soloist Christine Cairns (mezzo-soprano).

Instrumentation

- Strings: violins I & II, violas, cellos, double basses

- Woodwinds: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, tenor saxophone, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon

- Brass: 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba

- Percussion: timpani, snare drum, tom-tom, bass drum, cymbals, gong, tambourine, maracas, woodblock, anvil, steel plate, triangle, tubular bells, glockenspiel, xylophone

- Other: harp, organ

Recordings

The first recording of the film score reconstructed from the original manuscripts was made in 2003 by Frank Strobel conducting the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra and released on Capriccio Records.

| Year | Conductor | Orchestra and choir | Soloist | Version | Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1947 | Samuil Samosud | Russian State Radio Orchestra and Chorus | Lyudmila Legostayeva (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | Westminster WN 18144 |

| 1949 | Eugene Ormandy | Philadelphia Orchestra, Westminster Choir |

Jennie Tourel (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata (English) | Columbia Masterworks ML 4247 |

| 1954 | Mario Rossi | Vienna State Opera Orchestra and Chorus | Ana Maria Iriarte (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | Fontana BIG.331-L Vanguard VRS-451 |

| 1959 | Fritz Reiner | Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus | Rosalind Elias (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata (English) | RCA Victor Red Seal LSC-2395 |

| 1962 | Karel Ančerl | Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Prague Philharmonic Choir |

Věra Soukupová (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | Supraphon SUA 10429 Turnabout TV 34269 |

| 1962 | Thomas Schippers | New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Westminster Choir |

Lili Chookasian (contralto) | Cantata | Columbia Masterworks MS 6306 CBS Classics 61769 |

| 1966 | Yevgeny Svetlanov | USSR Symphony Orchestra, RSFSR Chorus |

Larisa Avdeyeva (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | Мелодия MEL CD 10 01831 |

| 1971 | André Previn | London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus | Anna Reynolds (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | His Master's Voice ASD 2800 |

| 1975 | Eugene Ormandy | Philadelphia Orchestra, The Mendelssohn Club of Philadelphia |

Betty Allen (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | RCA Red Seal ARL1-1151 |

| 1979 | Leonard Slatkin | St. Louis Symphony Orchestra and Chorus | Claudine Carlson (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab UDSACD 4009 |

| 1980 | Claudio Abbado | London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus | Elena Obraztsova (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | Deutsche Grammophon 0289-447-4192-6 |

| 1984 | Riccardo Chailly | Cleveland Orchestra and Chorus | Irina Arkhipova (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | Decca – 410 164-1 |

| 1987 | André Previn | Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, Los Angeles Master Chorale |

Christine Cairns (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | Angel Records S-36843 |

| 1988 | Neeme Järvi | Scottish National Orchestra and Chorus | Linda Finnie (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | Chandos CHAN 8584 |

| 1991 | Dmitri Kitayenko | Danish National Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus | Lyudmila Shemchuk (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | Chandos CHAN 9001 |

| 1992 | Charles Dutoit | Choeur et orchestre symphonique de Montréal | Jard van Nes (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | Decca London Records 430 506-2 |

| 1992 | Kurt Masur | Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Latvija Choir |

Carolyn Watkinson (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | Teldec Classics 9031-73284-2 |

| 1993 | Eduardo Mata | Dallas Symphony Orchestra and Chorus | Mariana Paunova (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | |

| 1993 | Zdeněk Mácal | Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra and Chorus | Janice Taylor (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | |

| 1994 | Semyon Bychkov | Choeur et orchestre de Paris | Marjana Lipovšek (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | |

| 1994 | Jean-Claude Casadesus | Orchestre national de Lille, Latvian State Choir |

Ewa Podleś (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | |

| 1995 | Yuri Temirkanov | St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra, Chorus of the St. Petersburg Teleradio Company, Chamber Chorus of St. Petersburg, St. Petersburg Chorus Capella "LIK" |

Yevgeniya Gorokhovskaya (mezzo-soprano) | Brohn | RCA Victor, also available on VHS and Laserdisc versions of the film released the same year |

| 2002 | Valery Gergiev | Kirov Orchestra and Chorus of the Mariinsky Theatre | Olga Borodina (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | |

| 2002 | Dmitry Yablonsky | Russian State Symphony Orchestra, Stanislavskiy Chorus |

Irina Gelakhova (mezzo-soprano) | Cantata | |

| 2003 | Frank Strobel | Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin, Ernst Senff Chor |

Marina Domashenko (mezzo-soprano) | Film score | Capriccio SACD 71 014 |

References

Notes

- ^ González Cueto, Irene (2016-05-23). "Warhol, Prokofiev, Eisenstein y la música - Cultural Resuena". Cultural Resuena (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2016-10-12.

- ^ The score of Alexander Nevsky is published by Schirmer, ISBN 0-634-03481-2

- ^ Herbert Glass. "About the piece: Cantata, Alexander Nevsky, Op. 78". LA Phil. Archived from the original on June 16, 2012. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Prokofiev: Werkverzeichnis (2015: p. 28)

- ^ a b Prokofiev: Werkverzeichnis (2015: p. 30)

- ^ Kravetz (2010: p. 10)

- ^ Kravetz (2010: p. 6)

- ^ Prokofiev: Werkverzeichnis (2015: p. 29)

- ^ a b Sergei Prokofiev, "Can There Be an End to Melody?", Pioneer magazine (1939), translation in Sergei Prokofiev, Autobiography, Articles, Reminiscences, compiled by S. Shlifstein, translated by Rose Prokofieva (Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific, 2000, ISBN 0-89875-149-7), 115–17 ).

- ^ Morrison (2009: pp. 228–9, 448)

- ^ Morag G. Kerr, "Prokofiev and His Cymbals", Musical Times 135 (1994), 608–609

- ^ Daniel Jaffe, BBC Prom concert programme, 29 July 2006, page 17

- ^ Morrison (2009: pg. 229)

- ^ Prokofiev (2000, p. 61)

- ^ Goberman, John (1995)

Sources

- Bartig, Kevin. Composing for the Red Screen: Prokofiev and Soviet Film, New York: Oxford University Press, 2013

- Goberman, John. Alexander Nevsky. Notes to RCA Red Seal CD 09026-61926-2, 1995

- Kravetz, Nelly. An Unknown Ivan the Terrible Oratorio, Three Oranges Journal No. 19, 2010

- Morrison, Simon. The People's Artist: Prokofiev's Soviet Years. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009

- Prokofiev, Sergei. Autobiography, Articles, Reminiscences, compiled by S. Shlifstein, translated by Rose Prokofieva. Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific, 2000, ISBN 0-89875-149-7

- Sergei Prokofiev: Werkverzeichnis, Hamburg: Musikverlage Hans Sikorski, 2015

External links

- Article from Three Oranges, the Journal of the Sergei Prokofiev Foundation, on the radio version of the Nevsky soundtrack.