Miranda (moon)

| |||||||||

| Discovery | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovered by | Gerard P. Kuiper | ||||||||

| Discovery date | February 16, 1948 | ||||||||

| Designations | |||||||||

Designation | Uranus V | ||||||||

| Pronunciation | /məˈrændə/[1][2] | ||||||||

| Adjectives | Mirandan,[3] Mirandian[4] | ||||||||

| Orbital characteristics | |||||||||

| 129,390 km | |||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.0013 | ||||||||

| 1.413479 d | |||||||||

Average orbital speed | 6.66 km/s (calculated) | ||||||||

| Inclination | 4.232° (to Uranus's equator) | ||||||||

| Satellite of | Uranus | ||||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||||

| Dimensions | 480 × 468.4 × 465.8 km | ||||||||

| 235.8±0.7 km (0.03697 Earths)[5] | |||||||||

| 700,000 km2 | |||||||||

| Volume | 54,835,000 km3 | ||||||||

| Mass | (6.4±0.3)×1019 kg[6] | ||||||||

Mean density | 1.20±0.15 g/cm3[7] | ||||||||

| 0.077 m/s2 | |||||||||

| 0.19 km/s | |||||||||

| synchronous | |||||||||

| 0° | |||||||||

| Albedo | 0.32 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| 15.8[9] | |||||||||

Miranda, also designated Uranus V, is the smallest and innermost of Uranus's five round satellites. It was discovered by Gerard Kuiper on 16 February 1948 at McDonald Observatory in Texas, and named after Miranda from William Shakespeare's play The Tempest.[10] Like the other large moons of Uranus, Miranda orbits close to its planet's equatorial plane. Because Uranus orbits the Sun on its side, Miranda's orbit is perpendicular to the ecliptic and shares Uranus' extreme seasonal cycle.

At just 470 km in diameter, Miranda is one of the smallest closely observed objects in the Solar System that might be in hydrostatic equilibrium (spherical under its own gravity). The only close-up images of Miranda are from the Voyager 2 probe, which made observations of Miranda during its Uranus flyby in January 1986. During the flyby, Miranda's southern hemisphere pointed towards the Sun, so only that part was studied.

Miranda probably formed from an accretion disc that surrounded the planet shortly after its formation, and, like other large moons, it is likely differentiated, with an inner core of rock surrounded by a mantle of ice. Miranda has one of the most extreme and varied topographies of any object in the Solar System, including Verona Rupes, a 20-kilometer-high scarp that is the highest cliff in the Solar System,[11][12] and chevron-shaped tectonic features called coronae. The origin and evolution of this varied geology, the most of any Uranian satellite, are still not fully understood, and multiple hypotheses exist regarding Miranda's evolution.

Discovery and name

Miranda was discovered on 16 February 1948 by planetary astronomer Gerard Kuiper using the McDonald Observatory's 82-inch (2,080 mm) Otto Struve Telescope.[10][13] Its motion around Uranus was confirmed on 1 March 1948.[10] It was the first satellite of Uranus discovered in nearly 100 years. Kuiper elected to name the object "Miranda" after the character in Shakespeare's The Tempest, because the four previously discovered moons of Uranus, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania and Oberon, had all been named after characters of Shakespeare or Alexander Pope. However, the previous moons had been named specifically after fairies,[14] whereas Miranda was a human. Subsequently, discovered satellites of Uranus were named after characters from Shakespeare and Pope, whether fairies or not. The moon is also designated Uranus V.

Orbit

Of Uranus's five round satellites, Miranda orbits closest to it, at roughly 129,000 km from the surface; about a quarter again as far as its most distant ring. Its orbital period is 34 hours, and, like that of the Moon, is synchronous with its rotation period, which means it always shows the same face to Uranus, a condition known as tidal locking. Miranda's orbital inclination (4.34°) is unusually high for a body so close to its planet – roughly ten times that of the other major Uranian satellites, and 73 times that of Oberon.[15] The reason for this is still uncertain; there are no mean-motion resonances between the moons that could explain it, leading to the hypothesis that the moons occasionally pass through secondary resonances, which at some point in the past led to Miranda being locked for a time into a 3:1 resonance with Umbriel, before chaotic behaviour induced by the secondary resonances moved it out of it again.[16] In the Uranian system, due to the planet's lesser degree of oblateness and the larger relative size of its satellites, escape from a mean-motion resonance is much easier than for satellites of Jupiter or Saturn.[17][18]

Composition and internal structure

At 1.2 g/cm3, Miranda is the least dense of Uranus's round satellites. That density suggests a composition of more than 60% water ice.[19] Miranda's surface may be mostly water ice, though it is far rockier than its corresponding satellites in the Saturn system, indicating that heat from radioactive decay may have led to internal differentiation, allowing silicate rock and organic compounds to settle in its interior.[20][21] Miranda is too small for any internal heat to have been retained over the age of the Solar System.[22] Miranda is the least spherical of Uranus's satellites, with an equatorial diameter 3% wider than its polar diameter. Only water has been detected so far on Miranda's surface, though it has been speculated that methane, ammonia, carbon monoxide or nitrogen may also exist at 3% concentrations.[21][23] These bulk properties are similar to Saturn's moon Mimas, though Mimas is smaller, less dense, and more oblate.[23]

Precisely how a body as small as Miranda could have enough internal energy to produce the myriad geological features seen on its surface is not established with certainty,[22] though the currently favoured hypothesis is that it was driven by tidal heating during a past time when it was in 3:1 orbital resonance with Umbriel.[24] The resonance would have increased Miranda's orbital eccentricity to 0.1, and generated tidal friction due to the varying tidal forces from Uranus.[25] As Miranda approached Uranus, tidal force increased; as it retreated, tidal force decreased, causing flexing that would have warmed Miranda's interior by 20 K, enough to trigger melting.[17][18][25] The period of tidal flexing could have lasted for up to 100 million years.[25] Also, if clathrate existed within Miranda, as has been hypothesised for the satellites of Uranus, it may have acted as an insulator, since it has a lower conductivity than water, increasing Miranda's temperature still further.[25] Miranda may have also once been in a 5:3 orbital resonance with Ariel, which would have also contributed to its internal heating. However, the maximum heating attributable to the resonance with Umbriel was likely about three times greater.[24]

Surface features

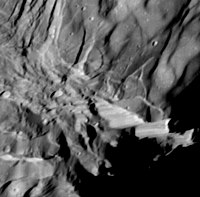

Due to Uranus's near-sideways orientation, only Miranda's southern hemisphere was visible to Voyager 2 when it arrived. The observed surface has patchwork regions of broken terrain, indicating intense geological activity in Miranda's past, and is criss-crossed by huge canyons, believed to be the result of extensional tectonics; as liquid water froze beneath the surface, it expanded, causing the surface ice to split, creating graben. The canyons are hundreds of kilometers long and tens of kilometers wide.[22] Miranda also has the largest-known cliff in the Solar System, Verona Rupes, which has a height of 20 km (12 mi).[12] Some of Miranda's terrain is possibly less than 100 million years old based on crater counts, while sizeable regions possess crater counts that indicate ancient terrain.[22][28]

While crater counts suggest that the majority of Miranda's surface is old, with a similar geological history to the other Uranian satellites,[22][29] few of those craters are particularly large, indicating that most must have formed after a major resurfacing event in its distant past.[20] Craters on Miranda also appear to possess softened edges, which could be the result either of ejecta or of cryovolcanism.[29] The temperature at Miranda's south pole is roughly 85 K, a temperature at which pure water ice adopts the properties of rock. Also, the cryovolcanic material responsible for the surfacing is too viscous to have been pure liquid water, but too fluid to have been solid water.[25][30] Rather, it is believed to have been a viscous, lava-like mixture of water and ammonia, which freezes at 176 K (−97 °C), or perhaps ethanol.[22]

Miranda's observed hemisphere contains three giant 'racetrack'-like grooved structures called coronae, each at least 200 km (120 mi) wide and up to 20 km (12 mi) deep, named Arden, Elsinore and Inverness after locations in Shakespeare's plays. Inverness is lower in altitude than the surrounding terrain (though domes and ridges are of comparable elevation), while Elsinore is higher.[21] The relative sparsity of craters on their surfaces means they overlay the earlier cratered terrain.[22] The coronae, which are unique to Miranda, initially defied easy explanation; one early hypothesis was that Miranda, at some time in its distant past, (prior to any of the current cratering)[21] had been completely torn to pieces, perhaps by a massive impact, and then reassembled in a random jumble.[21][26][31] The heavier core material fell through the crust, and the coronae formed as the water re-froze.[21]

However, the current favoured hypothesis is that they formed via extensional processes at the tops of diapirs, or upwellings of warm ice from within Miranda itself.[26][31][32][33] The coronae are surrounded by rings of concentric faults with a similar low-crater count, suggesting they played a role in their formation.[30] If the coronae formed through downwelling from a catastrophic disruption, then the concentric faults would present as compressed. If they formed through upwelling, such as by diapirism, then they would be extensional tilt blocks, and present extensional features, as current evidence suggests they do.[32] The concentric rings would have formed as ice moved away from the heat source.[34] The diapirs may have changed the density distribution within Miranda, which could have caused Miranda to reorient itself,[35] similar to a process believed to have occurred at Saturn's geologically active moon Enceladus. Evidence suggests the reorientation would have been as extreme as 60 degrees from the sub-Uranian point.[34] The positions of all the coronae require a tidal heating pattern consistent with Miranda being solid, and lacking an internal liquid ocean.[34] It is believed through computer modelling that Miranda may have an additional corona on the unimaged hemisphere.[36]

Observation and exploration

Miranda's apparent magnitude is +16.6, making it invisible to many amateur telescopes.[37] Virtually all known information regarding its geology and geography was obtained during the flyby of Uranus made by Voyager 2 on 25 January 1986,[20] The closest approach of Voyager 2 to Miranda was 29,000 km (18,000 mi)—significantly less than the distances to all other Uranian moons.[38] Of all the Uranian satellites, Miranda had the most visible surface.[23] The discovery team had expected Miranda to resemble Mimas, and found themselves at a loss to explain the moon's unique geography in the 24-hour window before releasing the images to the press.[29] In 2017, as part of its Planetary Science Decadal Survey, NASA evaluated the possibility of an orbiter to return to Uranus some time in the 2020s.[39] Uranus was the preferred destination over Neptune due to favourable planetary alignments meaning shorter flight times.[40]

See also

References

- ^ "Miranda". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Benjamin Smith (1903) The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia

- ^ Journal of Geophysical Research, v. 93 (1988)

- ^ Robertson (1929) The life of Miranda

- ^ Thomas, P. C. (1988). "Radii, shapes, and topography of the satellites of Uranus from limb coordinates". Icarus. 73 (3): 427–441. Bibcode:1988Icar...73..427T. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(88)90054-1.

- ^ R. A. Jacobson (2014) 'The Orbits of the Uranian Satellites and Rings, the Gravity Field of the Uranian System, and the Orientation of the Pole of Uranus'. The Astronomical Journal 148:5

- ^ Jacobson, R. A.; Campbell, J. K.; Taylor, A. H.; Synnott, S. P. (June 1992). "The masses of Uranus and its major satellites from Voyager tracking data and earth-based Uranian satellite data". The Astronomical Journal. 103 (6): 2068–2078. Bibcode:1992AJ....103.2068J. doi:10.1086/116211.

- ^ Hanel, R.; Conrath, B.; Flasar, F. M.; Kunde, V.; Maguire, W.; Pearl, J.; Pirraglia, J.; Samuelson, R.; Cruikshank, D. (4 July 1986). "Infrared Observations of the Uranian System". Science. 233 (4759): 70–74. Bibcode:1986Sci...233...70H. doi:10.1126/science.233.4759.70. PMID 17812891. S2CID 29994902.

- ^ "Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters". JPL (Solar System Dynamics). 2009-04-03. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- ^ a b c Kuiper, G. P., The Fifth Satellite of Uranus, Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, Vol. 61, No. 360, p. 129, June 1949

- ^ a b Chaikin, Andrew (2001-10-16). "Birth of Uranus' provocative moon still puzzles scientists". space.com. Imaginova Corp. p. 2. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ a b "APOD: 2016 November 27 - Verona Rupes: Tallest Known Cliff in the Solar System". apod.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ "Otto Struve Telescope". MacDonald Observatory. 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-21.

- ^ S G Barton. "The Names of the Satellites". Popular Astronomy. 54: 122.

- ^ Williams, Dr. David R. (2007-11-23). "Uranian Satellite Fact Sheet". NASA (National Space Science Data Center). Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- ^ Michele Moons and Jacques Henrard (June 1994). "Surfaces of Section in the Miranda-Umbriel 3:1 Inclination Problem". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 59 (2): 129–148. Bibcode:1994CeMDA..59..129M. doi:10.1007/bf00692129. S2CID 123594472.

- ^ a b Tittemore, William C.; Wisdom, Jack (March 1989). "Tidal evolution of the Uranian satellites: II. An explanation of the anomalously high orbital inclination of Miranda". Icarus. 78 (1): 63–89. Bibcode:1989Icar...78...63T. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(89)90070-5. hdl:1721.1/57632.

- ^ a b Malhotra, Renu; Dermott, Stanley F. (June 1990). "The role of secondary resonances in the orbital history of Miranda". Icarus. 85 (2): 444–480. Bibcode:1990Icar...85..444M. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(90)90126-T. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ^ B. A. Smith; et al. (4 July 1986). "Voyager 2 in the Uranian System: Imaging Science Results". Science. 233 (4759): 43–64. Bibcode:1986Sci...233...43S. doi:10.1126/science.233.4759.43. PMID 17812889. S2CID 5895824.

- ^ a b c E. Burgess (1988). Uranus and Neptune: The Distant Giants. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231064927.

- ^ a b c d e f S.K. Croft; L. A. Brown (1991). "Geology of the Uranian Satellites". In Jay T. Bergstralh; Ellis D. Miner; Mildred Shapley Matthews (eds.). Uranus. University of Arizona Press. pp. 309–319. ISBN 978-0816512089.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lindy Elkins-Tanton (2006). Uranus, Neptune, Pluto and the Outer Solar System. Facts On File. ISBN 978-0816051977.

- ^ a b c R. H. Brown (1990). "Physical Properties of the Uranian Satellites". In Jay T. Bergstralh; Ellis D. Miner; Mildred Shapley Matthews (eds.). Uranus. University of Arizona Press. pp. 513–528. ISBN 978-0816512089.

- ^ a b Tittemore, William C.; Wisdom, Jack (June 1990). "Tidal evolution of the Uranian satellites: III. Evolution through the Miranda-Umbriel 3:1, Miranda-Ariel 5:3, and Ariel-Umbriel 2:1 mean-motion commensurabilities" (PDF). Icarus. 85 (2): 394–443. Bibcode:1990Icar...85..394T. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(90)90125-S. hdl:1721.1/57632.

- ^ a b c d e S.K. Croft; R Greenberg (1991). "Geology of the Uranian Satellites". In Jay T. Bergstralh; Ellis D. Miner; Mildred Shapley Matthews (eds.). Uranus. University of Arizona Press. pp. 693–735. ISBN 978-0816512089.

- ^ a b c Chaikin, Andrew (2001-10-16). "Birth of Uranus' Provocative Moon Still Puzzles Scientists". Space.com. Imaginova Corp. Archived from the original on 2008-07-09. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- ^ "PIA00044: Miranda high resolution of large fault". JPL, NASA. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ S. J. Desch; J. C. Cook; W. Hawley & T. C. Doggett (2007-01-09). "Cryovolcanism on Charon and other Kuiper Belt Objects" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Science. XXXVIII (1338): 1901. Bibcode:2007LPI....38.1901D. Retrieved 2017-08-28.

- ^ a b c Miner, 1990, pp. 309-319

- ^ a b Ellis D. Miner (1990). Uranus: the planet, rings, and satellites. E. Horwood. ISBN 9780139468803.

- ^ a b "Bizarre Shape of Uranus' 'Frankenstein' Moon Explained". space.com. 3 October 2014. Retrieved 2017-08-28.

- ^ a b Pappalardo, Robert T.; Reynolds, Stephen J.; Greeley, Ronald (1997-06-25). "Extensional tilt blocks on Miranda: Evidence for an upwelling origin of Arden Corona". Journal of Geophysical Research. 102 (E6): 13, 369–13, 380. Bibcode:1997JGR...10213369P. doi:10.1029/97JE00802.

- ^ "Uranus Miranda - Teach Astronomy". m.teachastronomy.com. Archived from the original on 2014-10-15. Retrieved 2017-08-28.

- ^ a b c Hammond, Noah P.; Barr, Amy C. (September 2014). "Global resurfacing of Uranus's moon Miranda by convection". Geology. 42 (11): 931–934. Bibcode:2014Geo....42..931H. doi:10.1130/G36124.1.

- ^ Pappalardo, Robert T.; Greeley, Ronald (1993). "Structural evidence for reorientation of Miranda about a paleo-pole". In Lunar and Planetary Inst., Twenty-Fourth Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Part 3: N-Z. pp. 1111–1112. Bibcode:1993LPI....24.1111P.

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (3 October 2014). "Bizarre Shape of Uranus' 'Frankenstein' Moon Explained". space.com. space.com. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ Doug Scobel (2005). "Observe the Outer Planets!". The University of Michigan. Retrieved 2014-10-24.

- ^ Stone, E. C. (December 30, 1987). "The Voyager 2 Encounter with Uranus" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 92 (A13): 14, 873–14, 876. Bibcode:1987JGR....9214873S. doi:10.1029/JA092iA13p14873.

- ^ Vision and Voyages for Planetary Science in the Decade 2013–2022 Archived 2012-09-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Revisiting the ice giants: NASA study considers Uranus and Neptune missions. Jason Davis. The Planetary Society. 21 June 2017.

External links

- Miranda Profile at NASA's Solar System Exploration site

- Miranda page at The Nine Planets

- Miranda, a Moon of Uranus at Views of the Solar System

- Paul Schenk's 3D images and flyover videos of Miranda and other outer solar system satellites

- Miranda Nomenclature from the USGS Planetary Nomenclature web site