Newfoundland French

| Newfoundland French | |

|---|---|

| français terre-neuvien | |

| Native to | Canada |

| Region | Port au Port Peninsula, Newfoundland |

Native speakers | (undated figure of < 500[citation needed]) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF | fr-u-sd-canl |

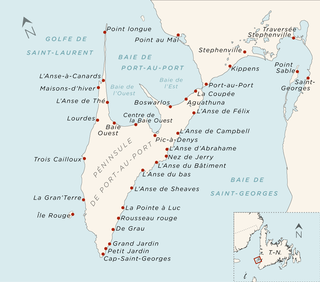

Historical Continental French settlements of Port-au-Port | |

Newfoundland French or Newfoundland Peninsular French (Template:Lang-fr), refers to the French spoken on the Port au Port Peninsula (part of the so-called “French Shore”) of Newfoundland. The francophones of the region can trace their origins to Continental French fishermen who settled in the late 1800s and early 1900s, rather than the Québécois. Some Acadians of the Maritimes also settled in the area. For this reason, Newfoundland French is most closely related to the Norman and Breton French[clarification needed] of nearby St-Pierre-et-Miquelon. Today, heavy contact with Acadian French—and especially widespread bilingualism with Newfoundland English—have taken their toll, and the community is in decline.

The degree to which lexical features of Newfoundland French constitute a distinct dialect is not presently known. It is uncertain how many speakers survive; the dialect could be moribund. There is a provincial advocacy organisation Fédération des Francophones de Terre-Neuve et du Labrador, representing both the Peninsular French and Acadian French communities.

Distribution

Newfoundland French communities include Cap-St-Georges, Petit Jardin, Grand Jardin, De Grau, Ruisseau Rouge, La Pointe à Luc, Trois Cailloux, La Grand’Terre, L’Anse-à-Canards, Maisons-d’Hiver and Lourdes. In addition, there is a town named Port Aux Basques on the western side of Newfoundland.

There are also nearby Acadian French communities in the Codroy Valley and Stephenville. These francophones speak in the Acadian dialect of French, and not Newfoundland French.

History

Origins

France contested ownership of Newfoundland from 1662 until 1713, when it ceded the island to Great Britain as part of the Treaty of Utrecht. During the Seven Years' War France (and Spain) vied for control of Newfoundland and the valuable fisheries off its shores. Fighting ceased in 1763, with French fishing rights to the western coast enshrined in the Treaty of Paris. This period saw an influx of Breton, Norman and Basque fishermen to the region, though most of the activity was seasonal, and French settlement before the late 1800s was forbidden. Despite British disapproval, the clandestine settlement continued, though without the benefit of schools and essential services. As a result, literacy among Francophones was uncommon in the twentieth century. In 1904 ownership of the region was transferred from France to the Colony of Newfoundland.

In addition to French immigration from Europe, Acadian immigrants arrived from Cape Breton Island and the Magdalen Islands to colonize Cape Saint-George, the Codroy Valley and Stephenville called "l'Anse-aux-Sauvages" (the Cove of Savages) beginning in the 19th century.[1] Until the middle of the 20th century, fishermen from Brittany who spoke Breton as their mother tongue, but were educated in French through the Jules Ferry schools, came to establish themselves on the Port-au-Port peninsula; this is arguably the primary cause for the differences between Newfoundland and Acadian French.[2]

Contact with anglophone populations, bilingualism, and assimilation

Contact between francophone and anglophone Newfoundlanders had been historically both limited and normally peaceful. In the first half of the twentieth century, the west coast of Newfoundland was roughly evenly distributed with English-speaking and French-speaking families, mostly working within their own linguistic communities. The major exception was the Catholic Church, wherein the priests were nearly always monolingually English-speaking. This strongly encouraged bilingualism in the francophone community and laid the seeds for assimilation.

In 1940, the establishment of the American air force base at Stephenville began French Newfoundland’s decline. Newfoundland French and Acadian French speakers who had lived and worked their entire lives in relative francophone isolation now found themselves at the heart of an American, Canadian, British and Newfoundlander anglophone economic centre. Families were grateful for the economic opportunities brought by the base, but transmission of French across generations dropped-off dramatically.

The absence of French-language education and the mandatory attendance of all children in English-speaking schools, as well as both radio and television programs in English, caused more recent generations to fail to master more complicated grammar and subject matter in French. English was becoming the only language of the educated.[3]

Patrice Brasseur, a French linguist, has made numerous visits to the island. In speaking with remaining elderly Newfoundland francophones, he has found that French-speaking children were often punished for speaking French at school.[4] Marriages between francophone and anglophone Catholics also became a contributing factor in assimilation, with intermarriages becoming more common from the 1930s onward.[5]

Confederation

Since 1949, when Newfoundland became a Canadian province, the use of French on the island has continued to decline. The presence of French was ignored by both governments, similarly to the Mi'kmaq populations, with there being no official position on the matter, but with the de facto policy of assimilation. As a result of the absence of francophone education and religious teaching, Newfoundland French is now spoken by only a handful of elderly residents and is considered moribund. Typically, Franco-Newfoundlanders in Newfoundland now speak Acadian French rather than the Newfoundland dialect, though a small number of families still speak a strongly inflected hybrid dialect. Today, 15,000 descendants of French settlers live in the province, and there is a movement to reestablish the Newfoundland dialect as the French language of education in the province. However, schoolchildren in the province are currently being introduced to either standard Quebec French, or to a heavily Acadian-influenced variety thereof.

Characteristics

According to Patrice Brasseur's articles " Les Représentations linguistiques des francophones de la péninsule de Port-au-Port " (2007)[6] and "Quelques aspects de la situation linguistique dans la communauté franco-terreneuvienne " (1995)[7] as well as according to the French Academy, some characteristics of French in Newfoundland can be kept in mind:

- the affrication of [k], noted tch or, most often, ch (with the frequent examples of cœur and quinze and cuiller and cuisine),

- the widespread use of English terms,

- the progressive extinction of the subjunctive form

- the use of septante, octante, and nonante

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ Waddell & Doran 1979, p. 150

- ^ Brasseur 2007, p. 67

- ^ Brasseur 2007, p. 78

- ^ Brasseur 1995, pp. 110–111

- ^ "Port-Au-Port Peninsula". www.heritage.nf.ca. Retrieved Oct 10, 2019.

- ^ Brasseur, Patrice. "Les Représentations linguistiques des francophones de la péninsule de Port-au-Port". Glottopol, Revue de sociolinguistique en ligne. 9: 66–79.[1] Archived 24 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ Brasseur, Patrice (1995). "Quelques aspects de la situation linguistique dans la communauté franco-terreneuvienne". Études canadiennes. 39: 103–117."Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). Retrieved 5 May 2011.

References

- [2]

- Bibliography

- Profil Port-au-port 2009 (in French)

- French Presence in Newfoundland

- The Two Traditions: The Art of Storytelling Amongst French Newfoundlanders By Gerald Thomas

- Le français parlé au 21e siècle By Michaël Abecassis, Laure Ayosso, Élodie Vialleton (in French)

- The Lexical Basis of Grammatical Borrowing. King, Ruth Elizabeth.

- Ballads and Sea-Songs of Newfoundland. Greenleaf, Elizabeth Bristol & Grace Yarrow Mansfield.

- Walking a tightrope: aboriginal people and their representations. David McNab, Ute Lischke.

- Entrevue avec violoniste terre-neuvien Emile Benoit (in French)