Liddle's syndrome

| Liddle's syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

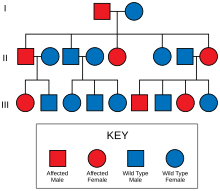

| Diagram of the inheritance of the syndrome | |

| Specialty | Nephrology |

Liddle's syndrome, also called Liddle syndrome,[1] is a genetic disorder inherited in an autosomal dominant manner that is characterized by early, and frequently severe, high blood pressure associated with low plasma renin activity, metabolic alkalosis, low blood potassium, and normal to low levels of aldosterone.[1] Liddle syndrome involves abnormal kidney function, with excess reabsorption of sodium and loss of potassium from the renal tubule, and is treated with a combination of low sodium diet and potassium-sparing diuretics (e.g. amiloride). It is extremely rare, with fewer than 30 pedigrees or isolated cases having been reported worldwide as of 2008.[2]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Children with Liddle syndrome are frequently asymptomatic. The first indication of the syndrome often is the incidental finding of hypertension during a routine physical exam. Because this syndrome is rare, it may only be considered by the treating physician after the child's hypertension does not respond to medications for lowering blood pressure.[citation needed]

Adults could present with nonspecific symptoms of low blood potassium, which can include weakness, fatigue, palpitations or muscular weakness (shortness of breath, constipation/abdominal distention or exercise intolerance). Additionally, long-standing hypertension could become symptomatic.[3]

Cause

[edit]This syndrome is caused by dysregulation of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) due to a genetic mutation at the 16p13-p12 locus. These channels are found on the surface of epithelial cells found in the kidneys, lungs, and sweat glands. The ENaC transports sodium ions from the adjacent lumen into the epithelial cells that line the lumen. The mutation changes a domain in the channel so it is no longer degraded correctly by the ubiquitin proteasome system. Specifically, the PY motif in the protein is deleted or altered so the E3 ligase (Nedd4) no longer recognizes the channel. This loss of ability to be degraded leads to high amounts of the channel being chronically present on the apical membrane of the epithelial cells that line the collecting ducts of the kidney.[4] This results in a hyperaldosteronism-like state, since aldosterone is typically responsible for creating and inserting these channels. The increased sodium resorption leads to increased resorption of water, and hypertension due to an increase in extracellular volume.[5]

Diagnosis

[edit]Evaluation of a child with persistent high blood pressure usually involves analysis of blood electrolytes and an aldosterone level, as well as other tests. In Liddle's disease, the serum sodium is typically elevated, the serum potassium is reduced,[6] and the serum bicarbonate is elevated. These findings are also found in hyperaldosteronism, another rare cause of hypertension in children. Primary hyperaldosteronism (also known as Conn's syndrome), is due to an aldosterone-secreting adrenal tumor (adenoma) or adrenal hyperplasia. Aldosterone levels are high in hyperaldosteronism, whereas they are low to normal in Liddle syndrome.[5]

A genetic study of the ENaC sequences can be requested to detect mutations (deletions, insertions, missense mutations) and get a diagnosis.[7]

Treatment

[edit]The treatment is a potassium-sparing diuretic, such as amiloride, that directly blocks the sodium channel.[8] Potassium-sparing diuretics that are effective for this purpose include amiloride and triamterene; spironolactone is not effective because it acts by regulating aldosterone and Liddle syndrome does not respond to this regulation. Amiloride is the only treatment option that is safe in pregnancy.[9] Medical treatment usually corrects both the hypertension and the hypokalemia, and as a result these patients may not require any potassium replacement therapy.[citation needed]

Liddle syndrome resolves completely after kidney transplantation.[10]

History

[edit]It is named after Dr. Grant Liddle (1921–1989), an American endocrinologist at Vanderbilt University, who described it in 1963.[11] Liddle described the syndrome in a family of people exemplifying a heritable, autosomal dominant hypertension with low potassium, renin, and aldosterone.[10]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Young, William. "Genetic disorders of the collecting tubule sodium channel: Liddle's syndrome and pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1". UpToDate.

- ^ Rossier BC, Schild L (October 2008). "Epithelial sodium channel: mendelian versus essential hypertension". Hypertension. 52 (4): 595–600. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.097147. PMID 18711011.

- ^ "Liddle Syndrome". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ "Epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) | Ion channels | IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY". www.guidetopharmacology.org.

- ^ a b Enslow BT, Stockand JD, Berman JM (2019). "Liddle's syndrome mechanisms, diagnosis and management". Integrated Blood Pressure Control. 12: 13–22. doi:10.2147/IBPC.S188869. PMC 6731958. PMID 31564964.

- ^ Brenner and Rector's The Kidney, 8th ed. CHAPTER 40 – Inherited Disorders of the Renal Tubule. Section on Liddle Syndrome. Accessed via MDConsult.

- ^ "Liddle Syndrome". Fact File. British Hypertension Society. February 2006. Archived from the original (doc) on 2011-07-25.

- ^ Spence, J. David (May 2017). "Rational Medical Therapy Is the Key to Effective Cardiovascular Disease Prevention". Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 33 (5): 626–634. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2017.01.003. PMID 28449833.

- ^ Awadalla M, Patwardhan M, Alsamsam A, Imran N (2017). "Management of Liddle Syndrome in Pregnancy: A Case Report and Literature Review". Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2017: 6279460. doi:10.1155/2017/6279460. PMC 5370477. PMID 28396810.

- ^ a b Ingelfinger, Julie R (2018). "Monogenic and Polygenic Contribution to Hypertension". In Flynn, JT (ed.). Pediatric Hypertension. Springer.

- ^ Liddle GW, Bledose T and Coppage Jr WS. A familial renal disorder simulating primary aldosteronism with negligible aldosterone secretion (1963). Trans. Assoc. Am. Physicians, 76, 199–213.

External links

[edit]- Pseudoaldosteronism at NIH's Office of Rare Diseases