Table-turning

| Part of a series on the |

| Paranormal |

|---|

|

Table-turning (also known as table-tapping, table-tipping or table-tilting) is a type of séance in which participants sit around a table, place their hands on it, and wait for rotations. The table was purportedly made to serve as a means of communicating with the spirits; the alphabet would be slowly spoken aloud and the table would tilt at the appropriate letter, thus spelling out words and sentences.[3] The process is similar to that of a Ouija board. Scientists and skeptics consider table-turning to be the result of the ideomotor effect, or of conscious trickery.[4][5][6]

History

When the movement of Modern Spiritualism first reached Europe from America in the winter of 1852–1853, the most popular method of consulting the spirits was for several persons to sit round a table, with their hands resting on it, and wait for the table to move. If the experiment was successful the table would rotate with considerable rapidity, and would occasionally rise in the air, or perform other movements.[3]

Whilst most spiritualists ascribed the table movements to the agency of spirits, two investigators, Count de Gasparin and Professor Thury of Geneva conducted a careful series of experiments by which they claimed to have demonstrated that the movements of the table were due to a physical force emanating from the bodies of the sitters, for which they proposed the name ectenic force. Their conclusion rested on the supposed elimination of all known physical causes for the movements; but it is doubtful from the description of the experiments whether the precautions taken were sufficient to exclude unconscious muscular action (the ideomotor effect) or even deliberate fraud.[3][7]

In England table-turning became a fashionable diversion and was practised all over the country in the year 1853. John Elliotson and his followers attributed the phenomena to mesmerism. The general public were content to find the explanation of the movements in spirits, animal magnetism, Odic force, galvanism, electricity, or even the rotation of the earth. Some Evangelical clergymen alleged that the spirits who caused the movements were of a diabolic nature.[3] In France, Allan Kardec studied the phenomenon and concluded in The Book on Mediums that some messages were caused by an outside intelligence as the message contained information that was not known to the group.

Scientific reception

The Scottish surgeon James Braid, the English physiologist W. B. Carpenter and others pointed out that the phenomena could depend upon the expectation of the sitters, and could be stopped altogether by appropriate suggestion.[3][8] Michel Eugène Chevreul[9][10] explained that the purported magical movement was due to involuntary and unconscious muscular reactions.

Michael Faraday[11] devised a simple apparatus which conclusively demonstrated that the movements he investigated were due to unconscious muscular action.[12] The apparatus consisted of two small boards, with glass rollers between them, the whole fastened together by india-rubber bands in such a manner that the upper board could slide under lateral pressure to a limited extent over the lower one. The occurrence of such lateral movement was at once indicated by means of an upright haystalk fastened to the apparatus. When by this means it was made clear to the experimenters that it was the fingers which moved the table, the phenomena generally ceased.[3] After this experimental approach, Faraday criticized the believers of table-turning.[13][14]

Faraday's work was followed up a century later by clinical psychologist Kenneth Batcheldor who pioneered the use of infrared video recording to observe experimental subjects in complete darkness.[citation needed]

Trickery

Apart from the ideomotor effect, conscious fraudulent table tipping has also been uncovered. Professional magicians and skeptics have exposed many of the methods utilized by mediums to tip tables.[15] The magician Chung Ling Soo described a method that involved a pin driven into the table and the use of a ring with a slot on the medium's finger. Once the pin entered the slot, the table could be lifted.[16] Another example comes from Eusapia Palladino, who used custom-made boots with soles that extended beyond the boots' edges in order to lift tables.[15]

According to John Mulholland:

The multiplicity of methods used to tip and raise tables in a séance is almost as great as the number of mediums performing the feat. One of the simplest was to slide the hands back until one or both of the medium's thumbs could catch hold of the table top. Another way was to exert no pressure on the table at all, and in the event that the sitter opposite the medium did press on the table, to permit the table to tip far enough away from him so that he could get the toe of one foot under the table leg. He would then immediately put pressure on his side, and, holding the table between his hands and his toe, move it about at will. By this method a small table can be made to float two feet off the floor... Another method was to catch the under side of the table top with the knee; and still another was merely to kick the table into the air.[17]

References

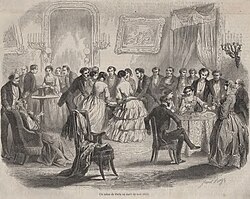

- ^ L'Illustration 1853-05-14, retrieved 2020-02-29

- ^ Geoghegan, Bernard Dionysius (2016-06-01). "Mind the Gap: Spiritualism and the Infrastructural Uncanny". Critical Inquiry. 42 (4): 899–922. doi:10.1086/686945. ISSN 0093-1896. S2CID 163534340.

- ^ a b c d e f One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Podmore, Frank (1911). "Table-turning". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 337.

- ^ Rawcliffe, D. H. (1987). Occult and Supernatural Phenomena. Dover Publications. p. 137

- ^ Zusne, Leonard; Jones, Warren H. (1989). Anomalistic Psychology: A Study of Magical Thinking. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-805-80507-9

- ^ Robert Todd Carroll. (2003). The Skeptic's Dictionary: A Collection of Strange Beliefs, Amusing Deceptions, and Dangerous Delusions. John Wiley & Sons. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-471-27242-7

- ^ Podmore, Frank. (1897). Studies in Psychical Research. New York: Putnam. p. 47 "If neither the feet nor the hands of the sitters could be employed, the knees could apparently have been used without much risk, and Thury clearly could not watch both the upper and under surfaces simultaneously. On the whole, though the experiments were conducted with care and a laudable desire not to exaggerate the importance of the facts observed, the experimenters do not appear to have sufficiently realised the possibilities of fraud; and their results add little evidence for action of a psychic, or, as Thury has preferred to name it, ectenic force."

- ^ Yeates, L.B., James Braid: Surgeon, Gentleman Scientist, and Hypnotist, Ph.D. Dissertation, School of History and Philosophy of Science, Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences, University of New South Wales, January 2013.

- ^ Michel Eugène Chevreul, “De la baguette”, 1854 (article)

- ^ Michel Eugène Chevreul, letter to André-Marie Ampère, 1833

- ^ Faraday, Michael (1859). . . London: Taylor & Francis. pp. 382–391 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Lamont, Peter. (2013). Extraordinary Beliefs: A Historical Approach to a Psychological Problem. Cambridge University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-107-01933-1

- ^ Faraday, Michael (1859). . . London: Taylor & Francis. pp. 463–492 – via Wikisource.

Perhaps it may be said, the delusion of table-moving is past, and need not be recalled before an audience like the present[4];—even granting this, let us endeavour to make the subject leave one useful result; let it serve for an example, not to pass into forgetfulness. It is so recent, and was received by the public in a manner so strange, as to justify a reference to it, in proof of the uneducated condition of the general mind. I do not object to table-moving, for itself; for being once stated, it becomes a fit, though a very unpromising subject for experiment; but I am opposed to the unwillingness of its advocates to investigate; their boldness to assert; the credulity of the lockers-on; their desire that the reserved and cautious objector should be in error; and I wish, by calling attention to these things, to make the general want of mental discipline and education manifest.

- ^ "The Right Chemistry: Turning the tables on the table turners". Montreal Gazette. Retrieved 2020-08-13.

"What a weak credulous, superstitious, ridiculous world ours is, as far as concerns the mind of man. How full of inconsistencies, contradictions, and absurdities it is." Those are not the words of some commentator bemoaning the lack of current critical thinking, although they well could be. They were uttered in 1853 by Michael Faraday, one of the greatest scientists who ever lived.

- ^ a b Randi, James (1995). An encyclopedia of claims, frauds, and hoaxes of the occult and supernatural: decidedly sceptical definitions of alternative realities. New York, NY: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-15119-5.

- ^ Soo, Chung Ling. (1898). Spirit Slate Writing and Kindred Phenomena. Munn & Company. p. 71-72

- ^ Mulholland, John. (1938). Beware Familiar Spirits. C. Scribner's Sons. p. 107. ISBN 0-684-16181-8

Further reading

- John Henry Anderson. (1855). The Fashionable Science of Parlour Magic. London. pp. 85–87

- Willis Dutcher. (1922). On the Other Side of the Footlights: An Expose of Routines, Apparatus and Deceptions Resorted to by Mediums, Clairvoyants, Fortune Tellers and Crystal Gazers in Deluding the Public. Berlin, WI: Heaney Magic. pp. 80–81

- F. Attfield Fawkes. (1920). Spiritualism Exposed. J. W. Arrowsmith Ltd. pp. 27–29

External links

- "Table-turning". Psi Encyclopedia. Society for Psychical Research.

- "Modern practical guide to table tilting". ASSAP. based on the work of Kenneth Batcheldor.

- Museum of Talking Boards (official website)