Mike Todd

Mike Todd | |

|---|---|

Todd at the Jones Beach Theater, 1952 | |

| Born | Avrom Hirsch Goldbogen June 22, 1907[1][2] Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Died | March 22, 1958 (aged 50) Grants, New Mexico, U.S. |

| Resting place | Beth Aaron Cemetery, Forest Park, Illinois |

| Occupation | Producer |

| Years active | 1933–1958 |

| Spouses | Bertha Freshman

(m. 1927; died 1946) |

| Partner | Evelyn Keyes (1953–1956) |

| Children | 2 |

Michael Todd (born Avrom Hirsch Goldbogen; June 22, 1907 – March 22, 1958) was an American theater and film producer, celebrated for his 1956 Around the World in 80 Days, which won an Academy Award for Best Picture. Actress Elizabeth Taylor was his third wife. Todd was the third of Taylor's seven husbands, and the only one whom Taylor did not divorce - Todd died in a private plane accident a year after their marriage. He was the driving force behind the development of the eponymous Todd-AO widescreen film format.

Early life

Todd was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, to Chaim Goldbogen (an Orthodox rabbi), and Sophia Hellerman, both of whom were Polish Jewish immigrants. His year of birth has been reported variously as 1907, 1908, 1909 or 1911,[3] but 1907 is the generally accepted year.[1][2] He was one of nine children in a poor family, the youngest son, and his siblings nicknamed him "Tod" (pronounced "Toat" in German) to mimic his difficulty pronouncing the word "coat". It was from this that his name was derived.[4][5]

The family later moved to Chicago, arriving on the day World War I ended.[5] Todd was expelled in the sixth grade for running a game of craps inside the school.[6] In high school, he produced the school play, The Mikado, which was considered a hit.[7] (As Mike Todd, he would produce a jazz version of the musical on Broadway in 1939.[8])

He eventually dropped out of high school, and worked at a variety of jobs, including shoe salesman and store window decorator. One of his first jobs was as a soda jerk. When the drugstore went out of business, Todd had acquired enough medical knowledge from his work there to be hired at Chicago's Michael Reese Hospital as a type of "security guard" to stop visitors from bringing in food that was not on the patient's diet.[5]

Career

Construction

Todd began his career in the construction business, where he made, and subsequently lost, a fortune. He opened the College of Bricklaying of America, buying the materials on credit to teach bricklaying. The school was forced to close when the Bricklayers' Union did not view the college as an accepted place of study.[5] Todd and his brother, Frank, next opened their own construction company.[5]

His first flirtation with the film industry was when he served as a contractor to Hollywood studios, soundproofing production stages during the transition from silent pictures to sound.[7] The company he owned with his brother went bankrupt when its financial backing failed in the early days of the Great Depression. Not yet 21, Todd had lost over $1 million (equivalent to about $18,239,044 in today's funds). Todd married the former Bertha Freshman on February 14, 1927, and was the father of an infant son with no home for his family.[9] Todd's subsequent business career was volatile, and failed ventures left him bankrupt many times.[10][11]

Theatrical impresario

During the 1933–1934 Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago, Todd produced an attraction called the "Flame Dance".[12] In this number, gas jets were designed to burn part of a dancer's costume, leaving her naked in appearance. The act attracted enough attention to bring an offer from the Casino de Paree nightclub in New York City. Todd got his first taste of Broadway with the engagement and was determined to find a way to work there.[5]

After seeing the Federal Theatre Project's Chicago run of The Swing Mikado, an adaptation of the Gilbert and Sullivan opera The Mikado with an all African-American cast conceived by Harry Minturn, Todd decided to do his own version on Broadway, The Hot Mikado, despite protests by the FTP.[13] The Hot Mikado, starring Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, opened on Broadway March 23, 1939.[14][15] The subsequent success of Todd's production, at the expense of the Chicago production, contributed to the financial crisis and ultimate demise of the Federal Theatre Project unit in Chicago.

Todd's Broadway success gave him the nerve to challenge showman Billy Rose. Todd visited Grover Whalen, president of the 1939 New York World's Fair, with a proposal to bring the Broadway show to the Fair. Whalen, eager to have the show at the fair, covered Todd's Broadway early closing costs. Rose, who had an exclusivity clause in his fair contract, met Todd at Lindy's, where Rose learned his contract covered new forms of entertainment only. To avoid any head-to-head competition, Rose quickly agreed to promote Todd's production along with his own.[16]

Todd ultimately produced 17 Broadway shows during his career, including the immensely successful burlesque revue Star and Garter starring comedian Bobby Clark, The Naked Genius written by and starring stripper Gypsy Rose Lee, and a 1945 production of Hamlet starring Maurice Evans.[18] His greatest successes were in musical comedy revues, typically featuring actresses in déshabillé, such as As the Girls Go (which also starred Clark) and Michael Todd's Peepshow.

Todd floated the idea of holding the 1945 Major League Baseball All-Star Game in newly liberated Berlin. Although baseball's new commissioner Happy Chandler was reportedly "intrigued" by the idea, it was ultimately dismissed as impractical. The game was finally cancelled due to wartime travel restrictions.

In 1952, Todd made a production of the Johann Strauss II operetta A Night in Venice, complete with floating gondolas at the then-newly constructed Jones Beach Theatre in Long Island, New York. It ran for two seasons.[19]

Widescreen cinema and film productions

In 1950, Mike Todd formed Cinerama with the broadcaster Lowell Thomas (who founded Capital Cities Communications) and the inventor Fred Waller.[21] The company was created to exploit Cinerama, a widescreen film process created by Waller that used three film projectors to create a giant composite image on a curved screen. The first Cinerama feature, This is Cinerama, was released in September 1952.

Before its release, Todd left the Cinerama Company to develop a widescreen process which would eliminate some of Cinerama's flaws.[22] The result was the Todd-AO process, designed by the American Optical Company.[23] The process was first used commercially for the successful film adaptation of Oklahoma! (1955). (Ironically, the producer had famously dismissed the stage musical during tryouts a decade earlier, quipping “No jokes, no legs, no chance.”) Todd soon produced the film for which he is best remembered, Michael Todd's Around the World in 80 Days, which debuted in cinemas on October 17, 1956. Costing $6 million to produce (equivalent to approximately $67,241,126[24]), the movie had grossed $33 million at the box office by the time of his death.[25] In 1957, Around the World in 80 Days won the Best Picture Academy Award.

In the 1950s Todd acquired the Harris and Selwyn Theaters in downtown Chicago. The Selwyn was renamed Michael Todd's Cinestage and converted into a showcase for Todd-AO productions, while the Harris was renamed the Michael Todd Theatre and operated as a conventional cinema. The facades of both theaters survive as part of the Goodman Theatre complex, although the interiors have been demolished.

A William Woolfolk novel from the early 1960s, entitled My Name Is Morgan, was considered to be loosely based on Todd's life and career.[26]

Personal life

At age 19, Todd married Bertha Freshman in Crown Point, Indiana, on Valentine's Day 1927. He had been interested in Freshman since his mid-teens, but needed to develop confidence before even asking her out.[5][27] In 1929, the couple's son, Mike Todd, Jr., was born.[5] The death of his father in 1931 was a turning point for Todd; he decided to change his name to Mike Todd on the day of his father's death.[5] Todd's wife, Bertha, died of a pneumothorax (collapsed lung) on August 12, 1946, in Santa Monica, California, while undergoing surgery at St. John's Hospital for a damaged tendon in her finger.[28][29][30][31] Todd and his wife were separated at the time of her death; less than a week before Freshman's death, he had filed for divorce.[30][32]

On July 5, 1947, Todd married actress Joan Blondell.[33] They divorced on June 8, 1950, after Blondell filed for divorce on the grounds of mental cruelty.[34]

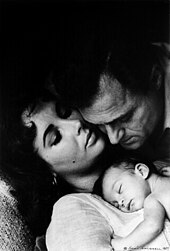

Todd's third marriage was to the actress Elizabeth Taylor, with whom he had a tempestuous relationship. The couple exchanged vows on February 2, 1957, in Mexico, in a ceremony performed by the mayor of Acapulco.[35] It was the third marriage for both the 24-year-old bride and her 49-year-old groom.[36] Mario Moreno, better known as Cantinflas, was their witness. Todd and Taylor had a daughter, Elizabeth Frances (Liza) Todd, born on August 6, 1957.[37]

Death

On March 22, 1958, Todd's private plane the Liz crashed near Grants, New Mexico. The plane, a twin-engine Lockheed Lodestar, suffered engine failure, while being flown overloaded in icing conditions at an altitude that was too high for only one engine working under the heavy load. The plane went out of control and crashed, killing all four on board.[38] Five days before the crash, Todd flew on this plane to Albuquerque, 78 miles (126 km) east of the crash site, to promote a screening of Michael Todd's Around the World in 80 Days.[39]

In addition to Todd, those who died in the crash were screenwriter and author Art Cohn, who was writing Todd's biography The Nine Lives of Michael Todd, pilot Bill Verner, and co-pilot Tom Barclay, a replacement for the plane's regular co-pilot.[39] Verner was a veteran military pilot who had flown heavily loaded Curtiss C-46 Commando cargo planes over The Hump between India and China.[40] Todd paid for the installation of two extra fuel tanks in his leased Lodestar aircraft; this made the aircraft weigh more than its official rating when all the tanks were full, without the flight crew, passengers or luggage aboard. Verner had flown the plane overloaded like this before without incident, including piloting Todd on trips over the Atlantic and around Europe. The tanks had been filled to capacity prior to the fatal flight.[38]

Todd was on his way to New York to accept the New York Friars Club "Showman of the Year" award. Taylor wanted to travel with her husband, but stayed home with a cold after Todd overruled her pleas to join the trip.[41][42] Just hours before the crash, Todd described the plane as safe as he phoned friends, including Joseph Mankiewicz and Kirk Douglas, in an attempt to recruit a gin rummy player for the flight: "Ah, c'mon," he said. "It's a good, safe plane. I wouldn't let it crash. I'm taking along a picture of Elizabeth, and I wouldn't let anything happen to her."[43]

His son, Mike Jr., wanted his father's body to be cremated after identification through dental records and brought to Albuquerque, New Mexico, but Taylor refused, saying he would not want cremation.[44] Todd's mother, aged 89 and a sanitarium patient at the time of her son's death, was not told of the accident as it was felt that the shock would be detrimental to her fragile health.[45] Todd was buried in Forest Park, Illinois, at Beth Aaron Cemetery in plot 66,[46] which is part of Jewish Waldheim Cemetery.[47][48] In his autobiography, Eddie Fisher, who considered himself to be Todd's best friend, stated:

There was a closed coffin, but I knew it was more for show than anything else. The plane had exploded on impact, and whatever remains were found couldn't be identified... The only items recovered from the wreckage were Mike's wedding ring and a pair of platinum cuff links I'd given him.[49]

In June 1977, Todd's remains were desecrated by graverobbers.[50] The thieves broke into his casket looking for a $100,000 diamond ring, which, according to rumor, Taylor had placed on her husband's finger prior to his burial.[51] The bag containing Todd's remains was found under a tree near his burial plot.[52] The bag and casket had been sealed in Albuquerque after Todd's remains were identified following the 1958 crash.[44][53] Todd's remains were once more identified through dental records and were reburied in a secret location.[51]

Selected Broadway productions

- Call Me Ziggy (Play, Farce, 1937)

- The Hot Mikado (Musical, Operetta, 1939)

- Something for the Boys (Musical, Comedy, 1943)

- Mexican Hayride (Musical, Comedy,1944)

- Up in Central Park (Musical, Comedy, 1945)

- As the Girls Go (Musical, Comedy, 1948)[54]

References

- ^ a b "Mike Todd". Encyclopedia.com. Cengage.

- ^ a b Taraborrelli, J. Randy (2006). Elizabeth. Grand Central Publishing. p. 98.

- ^ Cohn (1959), p. 15

- ^ Cohn (1959), p. 24

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cohn, Art (November 19, 1958). "His Name In Lights". Beaver Valley Times. p. 3. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ Mann, William J. (October 21, 2009). How to Be a Movie Star: Elizabeth Taylor in Hollywood 1941–1981. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 187. ISBN 978-0547417745.

- ^ a b DeAngelis, Gina, ed. (2003). Motion Pictures: Making Cinema Magic. Oliver Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1881508786.

- ^ "The Hot Mikado". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ Latham, Caroline; Sakol, Jeannie (1991). All About Elizabeth: Elizabeth Taylor, Public and Private. Penguin. p. 299. ISBN 978-0451402820.

- ^ Frumkes, Roy (1995). "Mike Todd, Jr. Interview". Classic Images. Archived from the original on February 16, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2010.

- ^ "Michael Todd Agrees to Bankruptcy Move". Billboard. May 1980. p. 31. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ Frankel, Noralee (March 3, 2011). Stripping Gypsy: The Life of Gypsy Rose Lee. Oxford University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0199754335.

- ^ Hatch, James V.; Hill, Errol G. (July 27, 2003). "The Great Depression and Federal Theatre". A History of African American Theatre. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 325–326. ISBN 978-0521624435.

- ^ "The Theatre: New Play in Manhattan: Apr. 3, 1939". Time. April 3, 1939. Archived from the original on December 14, 2008. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ Cohn, Art (November 10, 1958). "The Nine Lives of Michael Todd: A Hustler, He Never Looked Back". Beaver Valley Times. p. 13. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ Cohn, Art (November 12, 1958). "the Nine Lives of Michael Todd: Meets Billy Rose Head On". Argus Leader. Sioux Falls, South Dakota. p. 3. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ Doll, Bill (July 6, 1953). "Press release for A Night in Venice". Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ "Michael Todd Producer, Theatre Owner/Operator". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ^ Traubner, Richard (June 1, 2004) [1983]. Operetta: A Theatrical History. New York: Routledge. p. 256. ISBN 978-1135887827.

- ^ Cohn, Art (November 25, 1958). "Mike Todds' last Coup". Beaver Valley Times. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ "Cinema: The Third Dimension". Time. July 2, 1951. Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ Hecht, Jeff (October 1996). "The Amazing Optical Adventures of Todd-AO". Optics and Photonics News. 7 (10): 34. Bibcode:1996OptPN...7...34H. doi:10.1364/OPN.7.10.000034. Retrieved July 12, 2010.

- ^ Gunther, Roy C. Jr. (October 14, 1985). "Hollywood Comes to American Optical Co". The Southbridge News. Retrieved July 12, 2010.part one of 5

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "N.Y. Times Eulogizes Todd's Showmanship". Variety. March 26, 1958. p. 7. Retrieved October 12, 2021 – via Archive.org.

- ^ Woolfolk, William (February 8, 1962). "My Name Is Morgan". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ Cohn (1959) p. 24

- ^ "Cut Finger Proves Fatal". Pittsburgh Press. August 13, 1946. p. 14. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ "Analysis Ordered of Body of Producer's Wife". Spartanburg Herald-Journal. August 13, 1946. p. 3. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ a b "Lung Blamed for Death of Producer's Wife". Pittsburgh Press. August 22, 1946. p. 15. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ "Obituary Todd, Bertha nee Freshman". Chicago Tribune. August 15, 1946. p. 34. Retrieved March 25, 2011 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Sues For Divorce". Spokane Daily Chronicle. August 8, 1946. p. 9. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ "Joan Blondell Weds Mike Todd". Evening Independent. St. Petersburg, Florida. Associated Press. July 5, 1947. p. 13. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ "Joan Blondell Divorced". Spokane Daily Chronicle. United Press. June 9, 1950. p. 6. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ "Liz Taylor Weds Mike Todd As Eddie, Debbie, Stand By". Youngstown Vindicator. February 2, 1957. p. A-10. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ "Liz Taylor, Mike Todd Wed In Mexico". Toledo Blade. Associated Press. February 3, 1957. p. 4. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ "Milestones-August 19, 1957". Time. August 19, 1957. Archived from the original on November 1, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ a b "Civil Aeronautics Board Aircraft Accident Report: Lockheed Lodestar, N 300E, near Grants, New Mexico, March 22, 1958. File No. 2-0038". Civil Aeronautics Board. April 17, 1959.

- ^ a b "Producer Mike Todd Dies In Plane Crash". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. March 23, 1958. p. 2. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ "Famous Mike Todd Perishes in Crash". Abilene Reporter-News. Associated Press. March 23, 1958. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ "Showman Was Headed for Award". Waco Tribune-Herald. March 23, 1958. p. 7. Retrieved January 5, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mike Todd is Victim of Plane Crash". The Dispatch. Lexington, North Carolina. March 22, 1958. p. 1. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ "3 Refused Ride in Todd Plane". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. United Press. March 23, 1958. p. 1. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ a b "Todd Grave is Robbed in Illinois". Schenectady Gazette. June 28, 1977. p. 4. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ Bacon, James (March 24, 1958). "Liz Taylor Leaves For Mike Todd's Funeral". Ludington Daily News. p. 1. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ Matt Hucke. "Gravesite-Mike Todd". Matt Hucke. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ Hucke, Matt. "Jewish Waldheim Cemeteries". Matt Hucke. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ Bacon, James (March 26, 1958). "Brother Stirs Fuss at Rites for Mike Todd". The Gettysburg Times. p. 4.

- ^ Fisher, Eddie; Fisher, David (July 15, 2000). Been There, Done That. Macmillan. p. 157. ISBN 978-0312975586.

- ^ "Body of film producer snatched from cemetery". The Berkshire Eagle. United Press International. June 27, 1977. Retrieved December 8, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Mike Todd reburial in an undisclosed location". Ellensburg Daily Record. June 30, 1977. p. 6. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ "Bag of Bones Identified as Todd's". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. June 30, 1977. p. 2-A. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ "Theft of Todd's body baffling". Beaver County Times. June 28, 1977. p. A-4. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ "The Theater: New Musical in Manhattan November 22, 1948". Time. November 22, 1948. Archived from the original on February 1, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

Sources

- Dictionary of First Names, ISBN 0-304-36226-3

- City of Light : The Story of Fiber Optics, ISBN 0-19-516255-2

- Cohn, Art. The Nine Lives of Michael Todd. Hutchinson of London, 1959.

- Walker, Alexander. Elizabeth: The Life of Elizabeth Taylor. Grove Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8021-3769-5

External links

- Mike Todd at IMDb

- Mike Todd at the Internet Broadway Database

- Accident description for March 22, 1958 Mike Todd fatal crash at the Aviation Safety Network

- Mike Todd at Find a Grave – for a photograph of the original site, later vandalized by misinformed grave robbers

- 1907 births

- 1958 deaths

- 20th-century American businesspeople

- Accidental deaths in New Mexico

- Age controversies

- American people of Polish-Jewish descent

- American television producers

- American theatre managers and producers

- Burials in Forest Park, Illinois

- Golden Globe Award-winning producers

- Businesspeople from Minneapolis

- Producers who won the Best Picture Academy Award

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in 1958

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in the United States

- Film producers from Minnesota