Gastrointestinal disease

| Digestive disease | |

|---|---|

| |

| Organs of the gastrointestinal tract | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

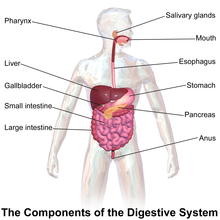

Gastrointestinal diseases (abbrev. GI diseases or GI illnesses) refer to diseases involving the gastrointestinal tract, namely the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine and rectum, and the accessory organs of digestion, the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas.

Oral disease

The oral cavity is part of the gastrointestinal system and as such the presence of alterations in this district can be the first sign of both systemic and gastrointestinal diseases.[1] By far the most common oral conditions are plaque-induced diseases (e.g., gingivitis, periodontitis, dental caries). Oral symptoms can be similar to lesions occurring elsewhere in the digestive tract, with a pattern of swelling, inflammation, ulcers, and fissures. If these signs are present, then patients are more likely to also have anal and esophageal lesions and experience other extra-intestinal disease manifestations.[2] Some diseases which involve other parts of the GI tract can manifest in the mouth, alone or in combination, including:

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease can cause acid erosion of the teeth and halitosis.

- Gardner's syndrome can be associated with failure of tooth eruption, supernumerary teeth, and dentigerous cysts.

- Peutz–Jeghers syndrome can cause dark spots on the oral mucosa or on the lips or the skin around the mouth.

- Several GI diseases, especially those associated with malabsorption, can cause recurrent mouth ulcers, atrophic glossitis, and angular cheilitis (e.g., Crohn's disease is sometimes termed orofacial granulomatosis when it involves the mouth alone).

- Sideropenic dysphagia can cause glossitis, angular cheilitis.[3]

Oesophageal disease

Oesophageal diseases include a spectrum of disorders affecting the oesophagus. The most common condition of the oesophagus in Western countries is gastroesophageal reflux disease,[4] which in chronic forms is thought to result in changes to the epithelium of the oesophagus, known as Barrett's oesophagus.[5]: 863–865

Acute disease might include infections such as oesophagitis, trauma caused by the ingestion of corrosive substances, or rupture of veins such as oesophageal varices, Boerhaave syndrome or Mallory-Weiss tears. Chronic diseases might include congenital diseases such as Zenker's diverticulum and esophageal webbing, and oesophageal motility disorders including the nutcracker oesophagus, achalasia, diffuse oesophageal spasm, and oesophageal stricture.[5]: 853, 863–868

Oesophageal disease may result in a sore throat, throwing up blood, difficulty swallowing or vomiting. Chronic or congenital diseases might be investigated using barium swallows, endoscopy and biopsy, whereas acute diseases such as reflux may be investigated and diagnosed based on symptoms and a medical history alone.[5]: 863–867

Gastric disease

Gastric diseases refer to diseases affecting the stomach. Inflammation of the stomach by infection from any cause is called gastritis, and when including other parts of the gastrointestinal tract called gastroenteritis. When gastritis persists in a chronic state, it is associated with several diseases, including atrophic gastritis, pyloric stenosis, and gastric cancer. Another common condition is gastric ulceration, peptic ulcers. Ulceration erodes the gastric mucosa, which protects the tissue of the stomach from the stomach acids. Peptic ulcers are most commonly caused by a bacterial Helicobacter pylori infection.[5] Epstein–Barr virus infection is another factor to induce gastric cancer.[6][7]

As well as peptic ulcers, vomiting blood may result from abnormal arteries or veins that have ruptured, including Dieulafoy's lesion and Gastric antral vascular ectasia. Congenital disorders of the stomach include pernicious anaemia, in which a targeted immune response against parietal cells results in an inability to absorb vitamin B12. Other common symptoms that stomach disease might cause include indigestion or dyspepsia, vomiting, and in chronic disease, digestive problems leading to forms of malnutrition.[5] : 850–853 In addition to routine tests, an endoscopy might be used to examine or take a biopsy from the stomach.[5] : 848

Intestinal disease

The small and large intestines may be affected by infectious, autoimmune, and physiological states. Inflammation of the intestines is called enterocolitis, which may lead to diarrhea.

Acute conditions affecting the bowels include infectious diarrhea and mesenteric ischaemia. Causes of constipation may include faecal impaction and bowel obstruction, which may in turn be caused by ileus, intussusception, volvulus. Inflammatory bowel disease is a condition of unknown aetiology, classified as either Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis, that can affect the intestines and other parts of the gastrointestinal tract. Other causes of illness include intestinal pseudoobstruction, and necrotizing enterocolitis.[5]: 850–862, 895–903

Diseases of the intestine may cause vomiting, diarrhoea or constipation, and altered stool, such as with blood in stool. Colonoscopy may be used to examine the large intestine, and a person's stool may be sent for culture and microscopy. Infectious disease may be treated with targeted antibiotics, and inflammatory bowel disease with immunosuppression. Surgery may also be used to treat some causes of bowel obstruction.[5]: 850–862

The normal thickness of the small intestinal wall is 3–5 mm,[8] and 1–5 mm in the large intestine.[9] Focal, irregular and asymmetrical gastrointestinal wall thickening on CT scan suggests a malignancy.[9] Segmental or diffuse gastrointestinal wall thickening is most often due to ischemic, inflammatory or infectious disease.[9] Though less common, medications such as ACE inhibitors can cause angioedema and small bowel thickening.[10]

Small intestine

The small intestine consists of the duodenum, jejunum and ileum. Inflammation of the small intestine is called enteritis, which if localised to just part is called duodenitis, jejunitis and ileitis, respectively. Peptic ulcers are also common in the duodenum.[5]: 879–884

Chronic diseases of malabsorption may affect the small intestine, including the autoimmune coeliac disease, infective tropical sprue, and congenital or surgical short bowel syndrome. Other rarer diseases affecting the small intestine include Curling's ulcer, blind loop syndrome, Milroy disease and Whipple's disease. Tumours of the small intestine include gastrointestinal stromal tumours, lipomas, hamartomas and carcinoid syndromes.[5]: 879–887

Diseases of the small intestine may present with symptoms such as diarrhoea, malnutrition, fatigue and weight loss. Investigations pursued may include blood tests to monitor nutrition, such as iron levels, folate and calcium, endoscopy and biopsy of the duodenum, and barium swallow. Treatments may include renutrition, and antibiotics for infections.[5]: 879–887

Large intestine

Diseases that affect the large intestine may affect it in whole or in part. Appendicitis is one such disease, caused by inflammation of the appendix. Generalised inflammation of the large intestine is referred to as colitis, which when caused by the bacteria Clostridium difficile is referred to as pseudomembranous colitis. Diverticulitis is a common cause of abdominal pain resulting from outpouchings that particularly affects the colon. Functional colonic diseases refer to disorders without a known cause, including irritable bowel syndrome and intestinal pseudoobstruction. Constipation may result from lifestyle factors, impaction of a rigid stool in the rectum, or in neonates, Hirschprung's disease.[5]: 913–915

Diseases affecting the large intestine may cause blood to be passed with stool, may cause constipation, or may result in abdominal pain or a fever. Tests that specifically examine the function of the large intestine include barium swallows, abdominal x-rays, and colonoscopy.[5]: 913–915

Rectum and anus

Diseases affecting the rectum and anus are extremely common, especially in older adults. Hemorrhoids, vascular outpouchings of skin, are very common, as is pruritus ani, referring to anal itchiness. Other conditions, such as anal cancer may be associated with ulcerative colitis or with sexually transmitted infections such as HIV. Inflammation of the rectum is known as proctitis, one cause of which is radiation damage associated with radiotherapy to other sites such as the prostate. Faecal incontinence can result from mechanical and neurological problems, and when associated with a lack of voluntary voiding ability is described as encopresis. Pain on passing stool may result from anal abscesses, small inflamed nodules, anal fissures, and anal fistulas.[5]: 915–916

Rectal and anal disease may be asymptomatic, or may present with pain when passing stools, fresh blood in stool, a feeling of incomplete emptying, or pencil-thin stools. In addition to regular tests, medical tests used to investigate the anus and rectum include the digital rectal exam and proctoscopy.[citation needed]

Accessory digestive gland disease

Hepatic

Hepatic diseases refers to those affecting the liver. Hepatitis refers to inflammation of liver tissue, and may be acute or chronic. Infectious viral hepatitis, such as hepatitis A, B and C, affect in excess of (X) million people worldwide. Liver disease may also be a result of lifestyle factors, such as fatty liver and NASH. Alcoholic liver disease may also develop as a result of chronic alcohol use, which may also cause alcoholic hepatitis. Cirrhosis may develop as a result of chronic hepatic fibrosis in a chronically inflamed liver, such as one affected by alcohol or viral hepatitis.[5]: 947–958

Liver abscesses are often acute conditions, with common causes being pyogenic and amoebic. Chronic liver disease, such as cirrhosis, may be a cause of liver failure, a state where the liver is unable to compensate for chronic damage, and unable to meet the metabolic demands of the body. In the acute setting, this may be a cause of hepatic encephalopathy and hepatorenal syndrome. Other causes of chronic liver disease are genetic or autoimmune disease, such as hemochromatosis, Wilson's disease, autoimmune hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis.[5]: 959–963, 971

Acute liver disease rarely results in pain, but may result in jaundice. Infectious liver disease may cause a fever. Chronic liver disease may result in a buildup of fluid in the abdomen, yellowing of the skin or eyes, easy bruising, immunosuppression, and feminization.[11] Portal hypertension is often present, and this may lead to the development of prominent veins in many parts of the body, such as oesophageal varices, and haemorrhoids.[5]: 959–963, 971–973

In order to investigate liver disease, a medical history, including regarding a person's family history, travel to risk-prone areas, alcohol use and food consumption, may be taken. A medical examination may be conducted to investigate for symptoms of liver disease. Blood tests may be used, particularly liver function tests, and other blood tests may be used to investigate the presence of the Hepatitis viruses in the blood, and ultrasound used. If ascites is present, abdominal fluid may be tested for protein levels.[5]: 921, 926–927

Pancreatic

Pancreatic diseases that affect digestion refers to disorders affecting the exocrine pancreas, which is a part of the pancreas involved in digestion.[citation needed]

One of the most common conditions of the exocrine pancreas is acute pancreatitis, which in the majority of cases relates to gallstones that have impacted in the pancreatic part of the biliary tree, or due to acute or chronic hazardous alcohol use or as a side-effect of ERCP. Other forms of pancreatitis include chronic and hereditary forms. Chronic pancreatitis may predispose to pancreatic cancer and is strongly linked to alcohol use. Other rarer diseases affecting the pancreas may include pancreatic pseudocysts, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, and pancreatic fistulas.[5]: 888–891

Pancreatic disease may present with or without symptoms. When symptoms occur, such as in acute pancreatitis, a person may experience acute-onset, severe mid-abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. In severe cases, pancreatitis may lead to rapid blood loss and systemic inflammatory response syndrome. When the pancreas is unable to secrete digestive enzymes, such as with a pancreatic cancer occluding the pancreatic duct, result in jaundice. Pancreatic disease might be investigated using abdominal x-rays, MRCP or ERCP, CT scans, and through blood tests such as measurement of the amylase and lipase enzymes.[5]: 888–894

Gallbladder and biliary tract

Diseases of the hepatobiliary system affect the biliary tract (also known as the biliary tree), which secretes bile in order to aid digestion of fats. Diseases of the gallbladder and bile ducts are commonly diet-related, and may include the formation of gallstones that impact in the gallbladder (cholecystolithiasis) or in the common bile duct (choledocholithiasis).[5]: 977–978

Gallstones are a common cause of inflammation of the gallbladder, called cholecystitis. Inflammation of the biliary duct is called cholangitis, which may be associated with autoimmune disease, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis, or a result of bacterial infection, such as ascending cholangitis.[5]: 977–978, 963–968

Disease of the biliary tree may cause pain in the upper right abdomen, particularly when pressed. Disease might be investigated using ultrasound or ERCP, and might be treated with drugs such as antibiotics or UDCA, or by the surgical removal of the gallbladder.[5]: 977–979

Cancer

The Wikipedia article "Gastrointestinal cancer" describes the specific malignant conditions of the gastrointestinal tract. In general, a significant factor in the etiology of gastrointestinal cancers appears to be excessive exposure of the digestive organs to bile acids.[12][13]

See also

References

- ^ "An overview on oral manifestations of gastrointestinal diseases". Italian Journal of Dental Medicine. 2018-12-31. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- ^ GIS. "Oral Manifestations of GI Diseases". Gastrointestinal Society. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- ^ Yamada T; Alpers DH; et al. (2009). Textbook of gastroenterology (5th ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Blackwell Pub. pp. 2774–2784. ISBN 978-1-4051-6911-0.

- ^ "Esophagus Disorders". Medline Plus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Nicki R. Colledge; Brian R. Walker; Stuart H. Ralston, eds. (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine. Illustrated by Robert Britton. (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.

- ^ Yau, Tung On; Tang, Ceen-Ming; Yu, Jun (2014-06-07). "Epigenetic dysregulation in Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma: disease and treatments". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (21): 6448–6456. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6448. ISSN 2219-2840. PMC 4047330. PMID 24914366.

- ^ Liang, Qiaoyi; Yao, Xiaotian; Tang, Senwei; Zhang, Jingwan; Yau, Tung On; Li, Xiaoxing; Tang, Ceen-Ming; Kang, Wei; Lung, Raymond W.M.; Li, Jing Woei; Chan, Ting Fung (December 2014). "Integrative Identification of Epstein–Barr Virus–Associated Mutations and Epigenetic Alterations in Gastric Cancer". Gastroenterology. 147 (6): 1350–1362.e4. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.036. PMID 25173755.

- ^ Ali Nawaz Khan. "Small-Bowel Obstruction Imaging". Medscape. Retrieved 2017-03-07. Updated: Sep 22, 2016

- ^ a b c Fernandes, Teresa; Oliveira, Maria I.; Castro, Ricardo; Araújo, Bruno; Viamonte, Bárbara; Cunha, Rui (2014). "Bowel wall thickening at CT: simplifying the diagnosis". Insights into Imaging. 5 (2): 195–208. doi:10.1007/s13244-013-0308-y. ISSN 1869-4101. PMC 3999365. PMID 24407923.

- ^ Sing, Ronald F.; Heniford, B. Todd; Augenstein, Vedra A. (1 March 2013). "Intestinal Angioedema Induced by Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors: An Underrecognized Cause of Abdominal Pain?". The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 113 (3): 221–223. doi:10.7556/jaoa. ISSN 0098-6151. PMID 23485983. S2CID 245177279.

- ^ Sharma B, Savio J (2018). Hepatic Cirrhosis. StatPearls. PMID 29494026. Retrieved 22 Sep 2020.

- ^ Bernstein, Harris; Bernstein, Carol; Payne, Claire M.; Dvorak, Katerina (2009). "Bile acids as endogenous etiologic agents in gastrointestinal cancer". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 15 (27): 3329–3340. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.3329. PMC 2712893. PMID 19610133.

- ^ Bernstein H, Bernstein C (January 2023). "Bile acids as carcinogens in the colon and at other sites in the gastrointestinal system". Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 248 (1): 79–89. doi:10.1177/15353702221131858. PMC 9989147. PMID 36408538.