Glenarm

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2012) |

| Glenarm | |

|---|---|

Glenarm Bay | |

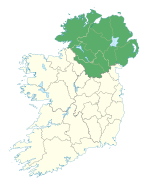

Location within Northern Ireland | |

| Population | 582 (2001 Census) |

| District | |

| County | |

| Country | Northern Ireland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Police | Northern Ireland |

| Fire | Northern Ireland |

| Ambulance | Northern Ireland |

Glenarm (from Irish Gleann Arma 'valley of the army') is a village in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It lies on the North Channel coast north of the town of Larne and the village of Ballygalley, and south of the village of Carnlough. It is situated in the civil parish of Tickmacrevan and the historic barony of Glenarm Lower.[2] It is part of Mid and East Antrim Borough Council and had a population of 1,851 people in the 2011 Census. Glenarm takes its name from the glen in which it lies, the southernmost of the nine Glens of Antrim.

History

Dating back to Norman times, the village is the family seat of the MacDonnells, who once occupied Dunluce Castle on the north coast. The village is now a Conservation Area, and its main street (Altmore Street) leads directly to Glenarm Forest, from which can be seen Glenarm Castle, on the far bank of the little river which runs through the village to the sea. The imposing entrance to Glenarm Castle, the Barbican Gate, is at the heart of the village. The Castle dates from 1750, with early 19th century alterations. Glenarm claims to be the oldest town in Ulster, having been granted a charter in the 12th century. The Barbican Gate to Glenarm Castle was restored by the Irish Landmark Trust, a conservation charity that saves buildings that are at risk of being lost.

In the 5th to 7th centuries (the beginning of the Early Christian period), Glenarm lay within the territory of the kingdom of Dal Riada. This covered coastal County Antrim from Glenarm to Bushmills. The inland boundary was formed by the watershed along the top of the Antrim hills. The coast of Co. Antrim south of Glenarm and west of Bushmills, as well as the lands south of the River Bush lay within the territories of another group of tribes called the Dal nAraide (pronounced Dalnary). A branch of the Dal nAraide, known as Latharna, seems to have occupied the coast from just south of Glenarm to Carrickfergus and beyond.

The area at one point came under threat from the Vikings who founded their only settlement of note in Ulster at "Ulfrek's fjord", present-day Larne.[3] According to Snorri Sturluson, an Icelandic historian, Connor, King of Ireland, defeated the raiding Orkney Vikings at "Ulfreksfjord" in 1018. The name Olderfleet is a corruption of "Ulfrek's fjord".[3]

The first castle at Glenarm is recorded in a 1270 Inquisition, where it is shown as being let to John or Robert Bisset by the Bishop of Down and Connor. As the Bissets are shown as tenants of the castle, it is likely it was built some time previously, probably by the de Galloways. It was situated on the site of a present-day Baptist church.

After a long war with Elizabeth I of England, political intrigues and the flight of the Irish chiefs overseas at the start of the 17th century, the area was earmarked for plantation by settlers from Great Britain who, being Protestant, were thought more likely to be loyal to the English Crown (see the Plantation of Ulster). This was an ad hoc private enterprise in Antrim and north Down and mainly involved lowland Scots. In 1603 Sir Randall MacDonnell, who in the intervening years had made peace with King James I, used his new-found influence to persuade him to not only grant him his native Glens of Antrim but also the north Antrim Route. However, Larne and its immediate environs were obtained by the English lord Sir Arthur Chichester.

On their return to Glenarm, a new castle began to be built on the opposite side of the river from the old one, on the site of the present castle. This new castle continued to be improved and added to until Sir Randal MacDonnell's death in 1636. The old castle must also have been repaired during this period as it was leased to the Donaldsons, who were kinsmen of the MacDonnells, at the start of the 17th century. Records show they still held the castle tenement in 1779, but it must have been abandoned before 1835 as a letter from this date refers to the 'foundations of a very extensive old castle which stood in the centre of the town until a few years ago'.

During the rebellion of 1641, Alexander MacDonnell, the Earl of Antrim's brother, who was in charge of and resided in Glenarm, fought on the native Irish side. He raised several regiments who were garrisoned in Glenarm under the command of Alester McColl. In 1642 when an invading Scots army, under the command of General Robert Munro, was sent by parliament to deal with the rebels they burnt Glenarm, including the new castle. They captured both Alexander and the Earl and they were imprisoned in Carrickfergus Castle. When peace was brought about the Acts of Settlement and Explanation restored all the MacDonnells' land to them. They did not, however, rebuild the castle in Glenarm at this time, but moved to Dunluce Castle and later Ballymegarry.

In the 17th century the religious needs of Glenarm were served by a small church and graveyard on Castle Street, at the site of the converted schoolhouse. The foundation date of this church is unknown, but Richard Dobbs, in his 1683 Descriptions of the county of Antrim, describes the church as being one of only three slate roofed buildings in the village. The Bridge into the Castle grounds was constructed beside this church and was completed in 1682. Dobbs also states that a Presbyterian meeting-house was to be found at some distance from the town. The position of this building is unknown, but map evidence suggests that it was in the vicinity of, or more likely under, the current non-subscribing Presbyterian church. Although no Catholic church was present, it is known that Father Edmund O’Moore became Glenarm’s first parish priest. He was ordained in 1669 and began officiating in Glenarm the next year. Due to religious suppression brought on by the Penal Laws, Catholic masses were often held in isolated spots, and there are several sites around Glenarm believed to have been used for this during these times. The closest site to Glenarm is called the Priest's Knowe or the Priest's Green, and it lies close to the Straidkilly Road, less than a mile from the village. An altar stone was known to exist here into the 19th century.

The 18th century saw the return of Lord Antrim to Glenarm and, with his funding, a number of major construction works were begun. A new castle was built over the remains of the castle destroyed in 1642. An inscribed stone shows that the castle was rebuilt by Alexander the fifth Earl of Antrim in the year 1756. This castle can still be seen as the central block of the current, much expanded, castle. In 1763 an agreement was reached between Lord Antrim and William McBride for the construction of St. Patrick's Church of Ireland on the site of the domestic quarters of the abandoned Franciscan friary. The grounds around the friary appear to have already been used as a graveyard at this time and this new church may have been partially built onto burials.

During the Famine

During the Great Irish Famine, the Glens of Antrim did not fare as poorly as the rest of Ireland. The Earl of Antrim, now resident in Glenarm, and the Marquess of Londonderry organised relief schemes of food and money for their tenants and built soup kitchens throughout the Glens. Glenarm’s soup kitchen is believed to have been to the rear of Altmore Street, along the river. The only other major historical event to occur in Glenarm during this period was in 1854, when a cholera epidemic afflicted the town. The epidemic began in the Bridge End Tavern and rapidly spread from house to house. A large percentage of the population eventually succumbed to the disease and was buried in a mass grave near the back wall of the graveyard of St. Patrick's Church.

Local politics

Glenarm has a local lodge of the Orange Order and a joint Royal Black Preceptory with nearby Carnlough. Glenarm is part of the Braid district No.9 and holds the annual 12 July celebrations 3 out of every 7 years. The local flute band is called Sir Edward Carson Memorial in memory of the famous Unionist leader. Previously there was a branch of the Catholic Ancient Order of Hibernians in Glenarm which paraded in the village, though this is no longer the case. Glenarm like its republican counterpart in the nearby village of Carnlough has cleaned up its public image by removing flags and political emblems to boost tourism in the area[4] though some sectarian tension still exists between elements in the two villages.[5]

The Troubles in Glenarm

On 21 September 1996 a Protestant, Kenneth Auld, age 47, died four days after being stabbed in a dispute involving the flying of an Ulster flag in Glenarm. Auld had been trying to prevent a group of Republicans from removing the flag when he was stabbed with a screwdriver.[6] A local man was charged with the killing but later acquitted.[7][8]

Places of interest

Glenarm Forest Park is an 800-acre (3.2 km2) nature preserve once part of the demesne of Glenarm Castle, but now in public and maintained by the Ulster Wildlife Trust. Other notable features include a salmon fishery and Glenarm Castle. The most recent addition to the village is the restoration of its distinctive limestone-built harbour.

Sports

Glenarm have three very successful sports teams. There is a Rowing Club (coastal) which trains over the summer months to prepare for the annual all Ireland Rowing Competition. In 2009 the club's Veteran Team won an all-Ireland silver medal at the championships held in Waterville, Co Kerry. The club which was founded in the late 19th century has been enjoying a revival in recent years and holds regular regattas with two other local coastal rowing clubs in Carnlough and Cairndhu Four oared gig racing has a measure of popularity in the village . Up until recently craft for this sport were the product of local boat builders and during the summer crews may be seen training out on the bay. A highlight of the gig racing calendar is the Annual Regatta which takes place in summer time and attracts crews from local clubs to take part in the local challenge. The local rowing club is Glenarm Rowing Club, who have over 10 members and are part of the Irish Coastal Rowing Federation. 2009's All Ireland a combined crew of Glenarm and Carnlough won a silver in the Veteran Men. The club was featured on the BBC documentary programme Coast.

There is also Glenarm Rovers F.C. that play Saturday morning football, managed by Terry Hastings. Glenarm Rovers have been promoted the two previous seasons but have struggled in their current division, though they managed to beat the drop.

Shane O'Neills GAA Club play just outside Glenarm in Feystown and field hurling teams at various adult and juvenile levels.

Events

- Highland Games tournaments are regularly held in Glenarm Castle.

- The Glenarm GAA club hosted the 2009 North Antrim Feis, which is a gathering of Irish culture. There were many GAA sports finals, arts competitions and Scór events.

- The Dalriada Festival is also held at Glenarm Castle and within the village, which celebrates sport, music and fine food from all over Scotland and Ireland,[9] as well as hosting traditional Ulster Scots cultural events.

- As part of the Dalriada Festival Glenarm Castle has started to host large outdoor concerts which as of 2012 has welcomed artists like General Fiasco, The Priests, Duke Special, Ronan Keating, Sharon Corr, Brian Houston, David Phelps and the likes.

- Summer Madness, Ireland's biggest Christian Festival, moved from its annual residence at the Kings Hall, Belfast, to Glenarm Castle in 2012. It is thought this Festival will return to Glenarm, on a yearly basis, for the foreseeable future.

Film location

Glenarm village was used in the film The Boys from County Clare (2003) which also used other locations in the Glens of Antrim. Glenarm Castle itself was used in Five Minutes of Heaven. The Christmas film A Christmas Star had scenes filmed near the marina of Glenarm village. BBC drama My Mother and Other Strangers used Altmore Street as its WWII setting during spring 2016 filming. Game of Thrones used Glenarm’s scenic background as one of many County Antrim’s cameo in the American HBO series.

2011 Census

Glenarm is classified as a small village or hamlet by the NI Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) (i.e. with population between 500 and 1,000 people). On Census day (27 March 2011) there were 1,851 people living in Glenarm. Of these:

- 21.72% were aged under 16 and 14.80% were aged 60 and over

- 52.47% of the population were male and 47.53% were female

- 3.09% of people aged 16–74 were unemployed.

- 43.1% were from a Catholic background and 53.4% were from a Protestant background

For more details see: NI Neighbourhood Information Service

See also

References

- ^ "Dunluce Castle – Ulster-Scots version" (PDF). NI Department of the Environment. Archived from the original on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Glenarm". IreAtlas Townlands Database. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ a b Jonathan Bardon (2001). A History of Ulster. p. 27. ISBN 0-85640-764-X.

- ^ Removal Of Flags Is Common Sense-Larne Times

- ^ Glenarm Bonfire Attacked-Larne Times

- ^ "Funeral of NI stabbing victim" The Irish Times 24 September 1996 Retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ "Conflict related deaths in 1996" Archived 2012-09-02 at the Wayback Machine British Irish Human Rights Watch Retrieved 24 July 2012

- ^ " Sobbing girl asks 'Who killed dad?" Highbeam 13 December 1997 Retrieved 18 November 2016

- ^ Dalriada Festival