Rheumatoid arthritis

| Rheumatoid arthritis | |

|---|---|

| |

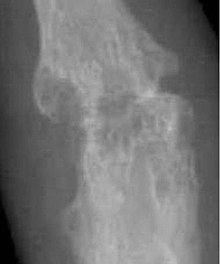

| A hand severely affected by rheumatoid arthritis. This degree of swelling and deformation does not typically occur with current treatment. | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

| Symptoms | Warm, swollen, painful joints[1] |

| Complications | Low red blood cells, inflammation around the lungs, inflammation around the heart[1] |

| Usual onset | Middle age[1] |

| Duration | Lifelong[1] |

| Causes | Unknown[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, medical imaging, blood tests[1][2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriatic arthritis, fibromyalgia[2] |

| Medication | Pain medications, steroids, Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs[1] |

| Frequency | 0.5–1% (adults in developed world)[3] |

| Deaths | 30,000 (2015)[4] |

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a long-term autoimmune disorder that primarily affects joints.[1] It typically results in warm, swollen, and painful joints.[1] Pain and stiffness often worsen following rest.[1] Most commonly, the wrist and hands are involved, with the same joints typically involved on both sides of the body.[1] The disease may also affect other parts of the body.[1] This may result in a low red blood cell count, inflammation around the lungs, and inflammation around the heart.[1] Fever and low energy may also be present.[1] Often, symptoms come on gradually over weeks to months.[2]

While the cause of rheumatoid arthritis is not clear, it is believed to involve a combination of genetic and environmental factors.[1] The underlying mechanism involves the body's immune system attacking the joints.[1] This results in inflammation and thickening of the joint capsule.[1] It also affects the underlying bone and cartilage.[1] The diagnosis is made mostly on the basis of a person's signs and symptoms.[2] X-rays and laboratory testing may support a diagnosis or exclude other diseases with similar symptoms.[1] Other diseases that may present similarly include systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriatic arthritis, and fibromyalgia among others.[2]

The goals of treatment are to reduce pain, decrease inflammation, and improve a person's overall functioning.[5] This may be helped by balancing rest and exercise, the use of splints and braces, or the use of assistive devices.[1][6][7] Pain medications, steroids, and NSAIDs are frequently used to help with symptoms.[1] Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), such as hydroxychloroquine and methotrexate, may be used to try to slow the progression of disease.[1] Biological DMARDs may be used when disease does not respond to other treatments.[8] However, they may have a greater rate of adverse effects.[9] Surgery to repair, replace, or fuse joints may help in certain situations.[1] Most alternative medicine treatments are not supported by evidence.[10][11]

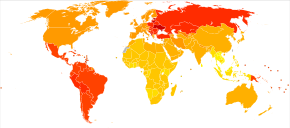

RA affects about 24.5 million people as of 2015.[12] This is between 0.5 and 1% of adults in the developed world with 5 and 50 per 100,000 people newly developing the condition each year.[3] Onset is most frequent during middle age and women are affected 2.5 times as frequently as men.[1] It resulted in 38,000 deaths in 2013, up from 28,000 deaths in 1990.[13] The first recognized description of RA was made in 1800 by Dr. Augustin Jacob Landré-Beauvais (1772–1840) of Paris.[14] The term rheumatoid arthritis is based on the Greek for watery and inflamed joints.[15]

Signs and symptoms

RA primarily affects joints, but it also affects other organs in more than 15–25% of cases.[16] Associated problems include cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, interstitial lung disease, infection, cancer, feeling tired, depression, mental difficulties, and trouble working.[17]

Joints

Arthritis of joints involves inflammation of the synovial membrane. Joints become swollen, tender and warm, and stiffness limits their movement. With time, multiple joints are affected (polyarthritis). Most commonly involved are the small joints of the hands, feet and cervical spine, but larger joints like the shoulder and knee can also be involved.[18]: 1098 Synovitis can lead to tethering of tissue with loss of movement and erosion of the joint surface causing deformity and loss of function.[2] The fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS), highly specialized mesenchymal cells found in the synovial membrane, have an active and prominent role in these pathogenic processes of the rheumatic joints.[19]

RA typically manifests with signs of inflammation, with the affected joints being swollen, warm, painful and stiff, particularly early in the morning on waking or following prolonged inactivity. Increased stiffness early in the morning is often a prominent feature of the disease and typically lasts for more than an hour. Gentle movements may relieve symptoms in early stages of the disease. These signs help distinguish rheumatoid from non-inflammatory problems of the joints, such as osteoarthritis. In arthritis of non-inflammatory causes, signs of inflammation and early morning stiffness are less prominent.[20] The pain associated with RA is induced at the site of inflammation and classified as nociceptive as opposed to neuropathic.[21] The joints are often affected in a fairly symmetrical fashion, although this is not specific, and the initial presentation may be asymmetrical.[18]: 1098

As the pathology progresses the inflammatory activity leads to tendon tethering and erosion and destruction of the joint surface, which impairs range of movement and leads to deformity. The fingers may suffer from almost any deformity depending on which joints are most involved. Specific deformities, which also occur in osteoarthritis, include ulnar deviation, boutonniere deformity (also "buttonhole deformity", flexion of proximal interphalangeal joint and extension of distal interphalangeal joint of the hand), swan neck deformity (hyperextension at proximal interphalangeal joint and flexion at distal interphalangeal joint) and "Z-thumb." "Z-thumb" or "Z-deformity" consists of hyperextension of the interphalangeal joint, fixed flexion and subluxation of the metacarpophalangeal joint and gives a "Z" appearance to the thumb.[18]: 1098 The hammer toe deformity may be seen. In the worst case, joints are known as arthritis mutilans due to the mutilating nature of the deformities.[22]

Skin

The rheumatoid nodule, which is sometimes in the skin, is the most common non-joint feature and occurs in 30% of people who have RA.[23] It is a type of inflammatory reaction known to pathologists as a "necrotizing granuloma". The initial pathologic process in nodule formation is unknown but may be essentially the same as the synovitis, since similar structural features occur in both. The nodule has a central area of fibrinoid necrosis that may be fissured and which corresponds to the fibrin-rich necrotic material found in and around an affected synovial space. Surrounding the necrosis is a layer of palisading macrophages and fibroblasts, corresponding to the intimal layer in synovium and a cuff of connective tissue containing clusters of lymphocytes and plasma cells, corresponding to the subintimal zone in synovitis. The typical rheumatoid nodule may be a few millimetres to a few centimetres in diameter and is usually found over bony prominences, such as the elbow, the heel, the knuckles, or other areas that sustain repeated mechanical stress. Nodules are associated with a positive RF (rheumatoid factor) titer, ACPA, and severe erosive arthritis. Rarely, these can occur in internal organs or at diverse sites on the body.[24]

Several forms of vasculitis occur in RA, but are mostly seen with long-standing and untreated disease. The most common presentation is due to involvement of small- and medium-sized vessels. Rheumatoid vasculitis can thus commonly present with skin ulceration and vasculitic nerve infarction known as mononeuritis multiplex.[25]

Other, rather rare, skin associated symptoms include pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet's syndrome, drug reactions, erythema nodosum, lobe panniculitis, atrophy of finger skin, palmar erythema, and skin fragility (often worsened by corticosteroid use).[citation needed]

Diffuse alopecia areata (Diffuse AA) occurs more commonly in people with rheumatoid arthritis.[26] RA is also seen more often in those with relatives who have AA.[26]

Lungs

Lung fibrosis is a recognized complication of rheumatoid arthritis. It is also a rare but well-recognized consequence of therapy (for example with methotrexate and leflunomide). Caplan's syndrome describes lung nodules in individuals with RA and additional exposure to coal dust. Exudative pleural effusions are also associated with RA.[27][28]

Heart and blood vessels

People with RA are more prone to atherosclerosis, and risk of myocardial infarction (heart attack) and stroke is markedly increased.[29][30][31] Other possible complications that may arise include: pericarditis, endocarditis, left ventricular failure, valvulitis and fibrosis.[32] Many people with RA do not experience the same chest pain that others feel when they have angina or myocardial infarction. To reduce cardiovascular risk, it is crucial to maintain optimal control of the inflammation caused by RA (which may be involved in causing the cardiovascular risk), and to use exercise and medications appropriately to reduce other cardiovascular risk factors such as blood lipids and blood pressure. Doctors who treat people with RA should be sensitive to cardiovascular risk when prescribing anti-inflammatory medications, and may want to consider prescribing routine use of low doses of aspirin if the gastrointestinal effects are tolerable.[32]

Blood

Anemia is by far the most common abnormality of the blood cells which can be caused by a variety of mechanisms. The chronic inflammation caused by RA leads to raised hepcidin levels, leading to anemia of chronic disease where iron is poorly absorbed and also sequestered into macrophages. The red cells are of normal size and color (normocytic and normochromic). A low white blood cell count usually only occurs in people with Felty's syndrome with an enlarged liver and spleen. The mechanism of neutropenia is complex. An increased platelet count occurs when inflammation is uncontrolled.[citation needed]

Other

Kidneys

Renal amyloidosis can occur as a consequence of untreated chronic inflammation.[33] Treatment with penicillamine and gold salts are recognized causes of membranous nephropathy.[citation needed]

Eyes

The eye can be directly affected in the form of episcleritis[34] or scleritis, which when severe can very rarely progress to perforating scleromalacia. Rather more common is the indirect effect of keratoconjunctivitis sicca, which is a dryness of eyes and mouth caused by lymphocyte infiltration of lacrimal and salivary glands. When severe, dryness of the cornea can lead to keratitis and loss of vision as well as being painful. Preventive treatment of severe dryness with measures such as nasolacrimal duct blockage is important.[citation needed]

Liver

Liver problems in people with rheumatoid arthritis may be due to the underlying disease process or as a result of the medications used to treat the disease.[35] A coexisting autoimmune liver disease, such as primary biliary cirrhosis or autoimmune hepatitis may also cause problems.[35]

Neurological

Peripheral neuropathy and mononeuritis multiplex may occur. The most common problem is carpal tunnel syndrome caused by compression of the median nerve by swelling around the wrist. Rheumatoid disease of the spine can lead to myelopathy. Atlanto-axial subluxation can occur, owing to erosion of the odontoid process and/or transverse ligaments in the cervical spine's connection to the skull. Such an erosion (>3mm) can give rise to vertebrae slipping over one another and compressing the spinal cord. Clumsiness is initially experienced, but without due care, this can progress to quadriplegia or even death.[36]

Constitutional symptoms

Constitutional symptoms including fatigue, low grade fever, malaise, morning stiffness, loss of appetite and loss of weight are common systemic manifestations seen in people with active RA.

Bones

Local osteoporosis occurs in RA around inflamed joints. It is postulated to be partially caused by inflammatory cytokines. More general osteoporosis is probably contributed to by immobility, systemic cytokine effects, local cytokine release in bone marrow and corticosteroid therapy.[citation needed]

Cancer

The incidence of lymphoma is increased, although it is uncommon and associated with the chronic inflammation, not the treatment of RA.[37][38] The risk of non-melanoma skin cancer is increased in people with RA compared to the general population, an association possibly due to the use of immunosuppression agents for treating RA.[39]

Teeth

Periodontitis and tooth loss are common in people with rheumatoid arthritis.[40]

Risk factors

RA is a systemic (whole body) autoimmune disease. Some genetic and environmental factors affect the risk for RA.

Genetic

A family history of RA increases the risk around three to five times; as of 2016, it was estimated that genetics may account for between 40 and 65% of cases of seropositive RA, but only around 20% for seronegative RA.[3] RA is strongly associated with genes of the inherited tissue type major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigen. HLA-DR4 is the major genetic factor implicated – the relative importance varies across ethnic groups.[41]

Genome-wide association studies examining single-nucleotide polymorphisms have found around one hundred genes associated with RA risk, with most of them involving the HLA system (particularly HLA-DRB1) which controls recognition of self versus nonself molecules; other mutations affecting co-stimulatory immune pathways, for example CD28 and CD40, cytokine signaling, lymphocyte receptor activation threshold (e.g., PTPN22), and innate immune activation appear to have less influence than HLA mutations.[3]

Environmental

There are established epigenetic and environmental risk factors for RA.[42][3] Smoking is an established risk factor for RA in Caucasian populations, increasing the risk three times compared to non-smokers, particularly in men, heavy smokers, and those who are rheumatoid factor positive.[43] Modest alcohol consumption may be protective.[44]

Silica exposure has been linked to RA.[45]

Negative findings

No infectious agent has been consistently linked with RA and there is no evidence of disease clustering to indicate its infectious cause,[41] but periodontal disease has been consistently associated with RA.[3]

The many negative findings suggest that either the trigger varies, or that it might, in fact, be a chance event inherent with the immune response.[46]

Pathophysiology

RA primarily starts as a state of persistent cellular activation leading to autoimmunity and immune complexes in joints and other organs where it manifests.[citation needed] The clinical manifestations of disease are primarily inflammation of the synovial membrane and joint damage, and the fibroblast-like synoviocytes play a key role in these pathogenic processes.[19] Three phases of progression of RA are an initiation phase (due to non-specific inflammation), an amplification phase (due to T cell activation), and chronic inflammatory phase, with tissue injury resulting from the cytokines, IL–1, TNF-alpha and IL–6.[22]

Non-specific inflammation

Factors allowing an abnormal immune response, once initiated, become permanent and chronic. These factors are genetic disorders which change regulation of the adaptive immune response.[3] Genetic factors interact with environmental risk factors for RA, with cigarette smoking as the most clearly defined risk factor.[43][47]

Other environmental and hormonal factors may explain higher risks for women, including onset after childbirth and hormonal medications. A possibility for increased susceptibility is that negative feedback mechanisms – which normally maintain tolerance – are overtaken by positive feedback mechanisms for certain antigens, such as IgG Fc bound by rheumatoid factor and citrullinated fibrinogen bound by antibodies to citrullinated peptides (ACPA - Anti–citrullinated protein antibody). A debate on the relative roles of B-cell produced immune complexes and T cell products in inflammation in RA has continued for 30 years, but neither cell is necessary at the site of inflammation, only autoantibodies to IgGFc, known as rheumatoid factors and ACPA, with ACPA having an 80% specificity for diagnosing RA.[48] As with other autoimmune diseases, people with RA have abnormally glycosylated antibodies, which are believed to promote joint inflammation.[49][page needed]

Amplification in the synovium

Once the generalized abnormal immune response has become established – which may take several years before any symptoms occur – plasma cells derived from B lymphocytes produce rheumatoid factors and ACPA of the IgG and IgM classes in large quantities. These activate macrophages through Fc receptor and complement binding, which is part of the intense inflammation in RA.[50] Binding of an autoreactive antibody to the Fc receptors is mediated through the antibody's N-glycans, which are altered to promote inflammation in people with RA.[49][page needed]

This contributes to local inflammation in a joint, specifically the synovium with edema, vasodilation and entry of activated T-cells, mainly CD4 in microscopically nodular aggregates and CD8 in microscopically diffuse infiltrates.[citation needed] Synovial macrophages and dendritic cells function as antigen-presenting cells by expressing MHC class II molecules, which establishes the immune reaction in the tissue.[citation needed]

Chronic inflammation

The disease progresses by forming granulation tissue at the edges of the synovial lining, pannus with extensive angiogenesis and enzymes causing tissue damage.[51] The fibroblast-like synoviocytes have a prominent role in these pathogenic processes.[19] The synovium thickens, cartilage and underlying bone disintegrate, and the joint deteriorates, with raised calprotectin levels serving as a biomarker of these events.[52]

Cytokines and chemokines attract and accumulate immune cells, i.e. activated T- and B cells, monocytes and macrophages from activated fibroblast-like synoviocytes, in the joint space. By signalling through RANKL and RANK, they eventually trigger osteoclast production, which degrades bone tissue.[3][53][page needed] The fibroblast-like synoviocytes that are present in the synovium during rheumatoid arthritis display altered phenotype compared to the cells present in normal tissues. The aggressive phenotype of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis and the effect these cells have on the microenvironment of the joint can be summarized into hallmarks that distinguish them from healthy fibroblast-like synoviocytes. These hallmark features of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis are divided into 7 cell-intrinsic hallmarks and 4 cell-extrinsic hallmarks.[19] The cell-intrinsic hallmarks are: reduced apoptosis, impaired contact inhibition, increased migratory invasive potential, changed epigenetic landscape, temporal and spatial heterogeneity, genomic instability and mutations, and reprogrammed cellular metabolism. The cell-extrinsic hallmarks of FLS in RA are: promotes osteoclastogenesis and bone erosion, contributes to cartilage degradation, induces synovial angiogenesis, and recruits and stimulates immune cells.[19]

Diagnosis

Imaging

X-rays of the hands and feet are generally performed when many joints affected. In RA, there may be no changes in the early stages of the disease or the x-ray may show osteopenia near the joint, soft tissue swelling, and a smaller than normal joint space. As the disease advances, there may be bony erosions and subluxation. Other medical imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound are also used in RA.[22][55]

Technical advances in ultrasonography like high-frequency transducers (10 MHz or higher) have improved the spatial resolution of ultrasound images depicting 20% more erosions than conventional radiography. Color Doppler and power Doppler ultrasound are useful in assessing the degree of synovial inflammation as they can show vascular signals of active synovitis. This is important, since in the early stages of RA, the synovium is primarily affected, and synovitis seems to be the best predictive marker of future joint damage.[56]

Blood tests

When RA is clinically suspected, a physician may test for rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs measured as anti-CCP antibodies).[57][page needed] It is positive in 75-85%, but a negative RF or CCP antibody does not rule out RA, rather, the arthritis is called seronegative, which is in about 15-25% of people with RA.[58] During the first year of illness, rheumatoid factor is more likely to be negative with some individuals becoming seropositive over time. RF is a non-specific antibody and seen in about 10% of healthy people, in many other chronic infections like hepatitis C, and chronic autoimmune diseases such as Sjögren's syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus. Therefore, the test is not specific for RA.[22]

Hence, new serological tests check for anti-citrullinated protein antibodies ACPAs . These tests are again positive in 61-75% of all RA cases, but with a specificity of around 95%.[59] As with RF, ACPAs are many times present before symptoms have started.[22]

The by far most common clinical test for ACPAs is the anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti CCP) ELISA. In 2008 a serological point-of-care test for the early detection of RA combined the detection of RF and anti-MCV with a sensitivity of 72% and specificity of 99.7%.[60][better source needed][61]

Other blood tests are usually done to differentiate from other causes of arthritis, like the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein, full blood count, kidney function, liver enzymes and other immunological tests (e.g., antinuclear antibody/ANA) are all performed at this stage. Elevated ferritin levels can reveal hemochromatosis, a mimic of RA, or be a sign of Still's disease, a seronegative, usually juvenile, variant of rheumatoid arthritis.[citation needed]

Classification criteria

In 2010, the 2010 ACR / EULAR Rheumatoid Arthritis Classification Criteria were introduced.[62]

The new criterion is not a diagnostic criterion but a classification criterion to identify disease with a high likelihood of developing a chronic form.[22] However a score of 6 or greater unequivocally classifies a person with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis.

These new classification criteria overruled the "old" ACR criteria of 1987 and are adapted for early RA diagnosis. The "new" classification criteria, jointly published by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) establish a point value between 0 and 10. Four areas are covered in the diagnosis:[62]

- joint involvement, designating the metacarpophalangeal joints, proximal interphalangeal joints, the interphalangeal joint of the thumb, second through fifth metatarsophalangeal joint and wrist as small joints, and shoulders, elbows, hip joints, knees, and ankles as large joints:

- Involvement of 1 large joint gives 0 points

- Involvement of 2–10 large joints gives 1 point

- Involvement of 1–3 small joints (with or without involvement of large joints) gives 2 points

- Involvement of 4–10 small joints (with or without involvement of large joints) gives 3 points

- Involvement of more than 10 joints (with involvement of at least 1 small joint) gives 5 points

- serological parameters – including the rheumatoid factor as well as ACPA – "ACPA" stands for "anti-citrullinated protein antibody":

- Negative RF and negative ACPA gives 0 points

- Low-positive RF or low-positive ACPA gives 2 points

- High-positive RF or high-positive ACPA gives 3 points

- acute phase reactants: 1 point for elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, ESR, or elevated CRP value (c-reactive protein)

- duration of arthritis: 1 point for symptoms lasting six weeks or longer

The new criteria accommodate to the growing understanding of RA and the improvements in diagnosing RA and disease treatment. In the "new" criteria serology and autoimmune diagnostics carries major weight, as ACPA detection is appropriate to diagnose the disease in an early state, before joints destructions occur. Destruction of the joints viewed in radiological images was a significant point of the ACR criteria from 1987.[63] This criterion no longer is regarded to be relevant, as this is just the type of damage that treatment is meant to avoid.

Differential diagnoses

| Type | WBC (per mm3) | % neutrophils | Viscosity | Appearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | <200 | 0 | High | Transparent |

| Osteoarthritis | <5000 | <25 | High | Clear yellow |

| Trauma | <10,000 | <50 | Variable | Bloody |

| Inflammatory | 2,000–50,000 | 50–80 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Septic arthritis | >50,000 | >75 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Gonorrhea | ~10,000 | 60 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Tuberculosis | ~20,000 | 70 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Inflammatory: Arthritis, gout, rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatic fever | ||||

Several other medical conditions can resemble RA, and need to be distinguished from it at the time of diagnosis:[66]

- Crystal induced arthritis (gout, and pseudogout) – usually involves particular joints (knee, MTP1, heels) and can be distinguished with an aspiration of joint fluid if in doubt. Redness, asymmetric distribution of affected joints, pain occurs at night and the starting pain is less than an hour with gout.

- Osteoarthritis – distinguished with X-rays of the affected joints and blood tests, older age, starting pain less than an hour, asymmetric distribution of affected joints and pain worsens when using joint for longer periods.

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) – distinguished by specific clinical symptoms and blood tests (antibodies against double-stranded DNA)

- One of the several types of psoriatic arthritis resembles RA – nail changes and skin symptoms distinguish between them

- Lyme disease causes erosive arthritis and may closely resemble RA – it may be distinguished by blood test in endemic areas

- Reactive arthritis – asymmetrically involves heel, sacroiliac joints and large joints of the leg. It is usually associated with urethritis, conjunctivitis, iritis, painless buccal ulcers, and keratoderma blennorrhagica.

- Axial spondyloarthritis (including ankylosing spondylitis) – this involves the spine, although an RA-like symmetrical small-joint polyarthritis may occur in the context of this condition.

- Hepatitis C – RA-like symmetrical small-joint polyarthritis may occur in the context of this condition. Hepatitis C may also induce rheumatoid factor auto-antibodies.

Rarer causes which usually behave differently but may cause joint pains:[66]

- Sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and Whipple's disease can also resemble RA.

- Hemochromatosis may cause hand joint arthritis.

- Acute rheumatic fever can be differentiated by a migratory pattern of joint involvement and evidence of antecedent streptococcal infection.

- Bacterial arthritis (such as by Streptococcus) is usually asymmetric, while RA usually involves both sides of the body symmetrically.

- Gonococcal arthritis (a bacterial arthritis) is also initially migratory and can involve tendons around the wrists and ankles.

Sometimes arthritis is in an undifferentiated stage (i.e. none of the above criteria is positive), even if synovitis is witnessed and assessed with ultrasound imaging.

Monitoring progression

Many tools can be used to monitor remission in rheumatoid arthritis.

- DAS28: Disease Activity Score of 28 joints (DAS28) is widely used as an indicator of RA disease activity and response to treatment. Joints included are (bilaterally): proximal interphalangeal joints (10 joints), metacarpophalangeal joints (10), wrists (2), elbows (2), shoulders (2) and knees (2). When looking at these joints, both the number of joints with tenderness upon touching (TEN28) and swelling (SW28) are counted. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is measured and the affected person makes a subjective assessment (SA) of disease activity during the preceding 7 days on a scale between 0 and 100, where 0 is "no activity" and 100 is "highest activity possible". With these parameters, DAS28 is calculated as:[67]

From this, the disease activity of the affected person can be classified as follows:[67]

| Current DAS28 |

DAS28 decrease from initial value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| > 1.2 | > 0.6 but ≤ 1.2 | ≤ 0.6 | ||

| ≤ 3.2 | Inactive | Good improvement | Moderate improvement | No improvement |

| > 3.2 but ≤ 5.1 | Moderate | Moderate improvement | Moderate improvement | No improvement |

| > 5.1 | Very active | Moderate improvement | No improvement | No improvement |

It is not always a reliable indicator of treatment effect.[68] One major limitation is that low-grade synovitis may be missed.[69]

- Other: Other tools to monitor remission in rheumatoid arthritis are: ACR-EULAR Provisional Definition of Remission of Rheumatoid arthritis, Simplified Disease Activity Index and Clinical Disease Activity Index.[70] Some scores do not require input from a healthcare professional and allow self-monitoring by the person, like HAQ-DI.[71][page needed]

Prevention

There is no known prevention for the condition other than the reduction of risk factors.[72]

Management

There is no cure for RA, but treatments can improve symptoms and slow the progress of the disease. Disease-modifying treatment has the best results when it is started early and aggressively.[73] The results of a recent systematic review found that combination therapy with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and non-TNF biologics plus methotrexate (MTX) resulted in improved disease control, Disease Activity Score (DAS)-defined remission, and functional capacity compared with a single treatment of either methotrexate or a biologic alone.[74]

The goals of treatment are to minimize symptoms such as pain and swelling, to prevent bone deformity (for example, bone erosions visible in X-rays), and to maintain day-to-day functioning.[75] This is primarily addressed with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs); dosed physical activity; analgesics and physical therapy may be used to help manage pain.[7][5][6] RA should generally be treated with at least one specific anti-rheumatic medication.[8] The use of benzodiazepines (such as diazepam) to treat the pain is not recommended as it does not appear to help and is associated with risks.[76]

Lifestyle

Regular exercise is recommended as both safe and useful to maintain muscles strength and overall physical function.[77] Physical activity is beneficial for people with rheumatoid arthritis who experience fatigue,[78] although there was little to no evidence to suggest that exercise may have an impact on physical function in the long term, a study found that carefully dosed exercise has shown significant improvements in patients with RA.[6][79] Moderate effects have been found for aerobic exercises and resistance training on cardiovascular fitness and muscle strength in RA. Furthermore, physical activity had no detrimental side effects like increased disease activity in any exercise dimension.[80] It is uncertain if eating or avoiding specific foods or other specific dietary measures help improve symptoms.[81] Occupational therapy has a positive role to play in improving functional ability in people with rheumatoid arthritis.[82] Weak evidence supports the use of wax baths (thermotherapy) to treat arthritis in the hands.[83]

Educational approaches that inform people about tools and strategies available to help them cope with rheumatoid arthritis may improve a person's psychological status and level of depression in the shorter-term.[84] The use of extra-depth shoes and molded insoles may reduce pain during weight-bearing activities such as walking.[85] Insoles may also prevent the progression of bunions.[85]

Disease modifying agents

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are the primary treatment for RA.[8] They are a diverse collection of drugs, grouped by use and convention. They have been found to improve symptoms, decrease joint damage, and improve overall functional abilities.[8] DMARDs should be started early in the disease as they result in disease remission in approximately half of people and improved outcomes overall.[8]

The following drugs are considered as DMARDs: methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, leflunomide, TNF-alpha inhibitors (certolizumab, infliximab and etanercept), abatacept, and anakinra. Rituximab and tocilizumab are monoclonal antibodies and are also DMARDs.[8] Use of tocilizumab is associated with a risk of increased cholesterol levels.[86]

Hydroxychloroquine, apart from its low toxicity profile, is considered effective in the moderate RA treatment.[87]

The most commonly used agent is methotrexate with other frequently used agents including sulfasalazine and leflunomide.[8] Leflunomide is effective when used from 6–12 months, with similar effectiveness to methotrexate when used for 2 years.[88] Sulfasalazine also appears to be most effective in the short-term treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.[89] Sodium aurothiomalate (gold) and cyclosporin are less commonly used due to more common adverse effects.[8] However, cyclosporin was found to be effective in the progressive RA when used up to one year.[90] Agents may be used in combinations however, people may experience greater side effects.[8][91] Methotrexate is the most important and useful DMARD and is usually the first treatment.[8][5][92] A combined approach with methotrexate and biologics improves ACR50, HAQ scores and RA remission rates.[93] Triple therapy consisting of methotrexate, sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine may also effectively control disease activity.[94] Adverse effects should be monitored regularly with toxicity including gastrointestinal, hematologic, pulmonary, and hepatic.[92] Side effects such as nausea, vomiting or abdominal pain can be reduced by taking folic acid.[95]

A 2015 Cochrane review found rituximab with methotrexate to be effective in improving symptoms compared to methotrexate alone.[96] Rituximab works by decreasing levels of B-cells (immune cell that is involved in inflammation). People taking rituximab had improved pain, function, reduced disease activity and reduced joint damage based on x-ray images. After 6 months, 21% more people had improvement in their symptoms using rituximab and methotrexate.[96]

Biological agents should generally only be used if methotrexate and other conventional agents are not effective after a trial of three months.[8] They are associated with a higher rate of serious infections as compared to other DMARDs.[97] Biological DMARD agents used to treat rheumatoid arthritis include: tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) blockers such as infliximab; interleukin 1 blockers such as anakinra, monoclonal antibodies against B cells such as rituximab, and tocilizumab T cell co-stimulation blocker such as abatacept. They are often used in combination with either methotrexate or leflunomide.[8][3] Biologic monotherapy or tofacitinib with methotrexate may improve ACR50, RA remission rates and function.[98][99] Abatacept should not be used at the same time as other biologics.[100] In those who are well controlled (low disease activity) on TNF blockers, decreasing the dose does not appear to affect overall function.[101] Discontinuation of TNF blockers (as opposed to gradually lowering the dose) by people with low disease activity may lead to increased disease activity and may affect remission, damage that is visible on an x-ray, and a person's function.[101] People should be screened for latent tuberculosis before starting any TNF blockers therapy to avoid reactivation of tuberculosis.[22]

TNF blockers and methotrexate appear to have similar effectiveness when used alone and better results are obtained when used together. Golimumab is effective when used with methotraxate.[102] TNF blockers may have equivalent effectiveness with etanercept appearing to be the safest.[103] Injecting etanercept, in addition to methotrexate twice a week may improve ACR50 and decrease radiographic progression for up to 3 years.[104] Abatacept appears effective for RA with 20% more people improving with treatment than without but long term safety studies are yet unavailable.[105] Adalimumab slows the time for the radiographic progression when used for 52 weeks.[106] However, there is a lack of evidence to distinguish between the biologics available for RA.[107] Issues with the biologics include their high cost and association with infections including tuberculosis.[3] Use of biological agents may reduce fatigue.[108] The mechanism of how biologics reduce fatigue is unclear.[108]

Anti-inflammatory and analgesic agents

Glucocorticoids can be used in the short term and at the lowest dose possible for flare-ups and while waiting for slow-onset drugs to take effect.[8][3][109] Combination of glucocorticoids and conventional therapy has shown a decrease in rate of erosion of bones.[110] Steroids may be injected into affected joints during the initial period of RA, prior to the use of DMARDs or oral steroids.[111]

Non-NSAID drugs to relieve pain, like paracetamol may be used to help relieve the pain symptoms; they do not change the underlying disease.[5] The use of paracetamol may be associated with the risk of developing ulcers.[112]

NSAIDs reduce both pain and stiffness in those with RA but do not affect the underlying disease and appear to have no effect on people's long term disease course and thus are no longer first line agents.[3][113] NSAIDs should be used with caution in those with gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, or kidney problems.[114][115][116][112] Rofecoxib was withdrawn from the global market as its long-term use was associated to an increased risk of heart attacks and strokes.[117] Use of methotrexate together with NSAIDs is safe, if adequate monitoring is done.[118] COX-2 inhibitors, such as celecoxib, and NSAIDs are equally effective.[119][120] A 2004 Cochrane review found that people preferred NSAIDs over paracetamol.[121] However, it is yet to be clinically determined whether NSAIDs are more effective than paracetamol.[121]

The neuromodulator agents topical capsaicin may be reasonable to use in an attempt to reduce pain.[122] Nefopam by mouth and cannabis are not recommended as of 2012 as the risks of use appear to be greater than the benefits.[122]

Limited evidence suggests the use of weak oral opioids but the adverse effects may outweigh the benefits.[123]

Alternatively, physical therapy has been tested and shown as an effective aid in reducing pain in patients with RA. As most RA is detected early and treated aggressively, physical therapy plays more of a preventative and compensatory role, aiding in pain management alongside regular rheumatic therapy.[7]

Surgery

Especially for affected fingers, hands, and wrists, synovectomy may be needed to prevent pain or tendon rupture when drug treatment has failed. Severely affected joints may require joint replacement surgery, such as knee replacement. Postoperatively, physiotherapy is always necessary.[18]: 1080, 1103 There is insufficient evidence to support surgical treatment on arthritic shoulders.[124]

Physiotherapy

For people with RA, physiotherapy may be used together with medical management.[125] This may include cold and heat application, electronic stimulation, and hydrotherapy.[125]

Physiotherapy promotes physical activity. In RA, physical activity like exercise in the appropriate dosage (frequency, intensity, time, type, volume, progression) and physical activity promotion is effective in improving cardiovascular fitness, muscle strength, and maintaining a long term active lifestyle. Physical activity promotion according to the public health recommendations should be an integral part of standard care for people with RA and other arthritic diseases.[6]

Alternative medicine

In general, there is not enough evidence to support any complementary health approaches for RA, with safety concerns for some of them. Some mind and body practices and dietary supplements may help people with symptoms and therefore may be beneficial additions to conventional treatments, but there is not enough evidence to draw conclusions.[11] A systematic review of CAM modalities (excluding fish oil) found that " The available evidence does not support their current use in the management of RA.".[126] Studies showing beneficial effects in RA on a wide variety of CAM modalities are often affected by publication bias and are generally not high quality evidence such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs).[10]

A 2005 Cochrane review states that low level laser therapy can be tried to improve pain and morning stiffness due to rheumatoid arthritis as there are few side-effects.[127]

There is limited evidence that Tai Chi might improve the range of motion of a joint in persons with rheumatoid arthritis.[128][129] The evidence for acupuncture is inconclusive[130] with it appearing to be equivalent to sham acupuncture.[131]

A Cochrane review in 2002 showed some benefits of the electrical stimulation as a rehabilitation intervention to improve the power of the hand grip and help to resist fatigue.[132] D‐penicillamine may provide similar benefits as DMARDs but it is also highly toxic.[133] Low-quality evidence suggests the use of therapeutic ultrasound on arthritic hands.[134] Potential benefits include increased grip strength, reduced morning stiffness and number of swollen joints.[134] There is tentative evidence of benefit of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) in RA.[135] Acupuncture‐like TENS (AL-TENS) may decrease pain intensity and improve muscle power scores.[135]

Low-quality evidence suggests people with active RA may benefit from assistive technology.[136] This may include less discomfort and difficulty such as when using an eye drop device.[136] Balance training is of unclear benefits.[137]

Dietary supplements

- Fatty acids

- Gamma-linolenic acid, an omega-6 fatty acid, may reduce pain, tender joint count and stiffness, and is generally safe.[138] For omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (found in fish oil), a meta-analysis reported a favorable effect on pain, although confidence in the effect was considered moderate. The same review reported less inflammation but no difference in joint function.[139] A review examined the effect of marine oil omega-3 fatty acids on pro-inflammatory eicosanoid concentrations; leukotriene4 (LTB4) was lowered in people with rheumatoid arthritis but not in those with non-autoimmune chronic diseases. (LTB4) increases vascular permeabiltity and stimulates other inflammatory substances.[140] A third meta-analysis looked at fish consumption. The result was a weak, non-statistically significant inverse association between fish consumption and RA.[141] A fourth review limited inclusion to trials in which people eat ≥2.7 g/day for more than three months. Use of pain relief medication was decreased, but improvements in tender or swollen joints, morning stiffness and physical function were not changed.[142] Collectively, the current evidence is not strong enough to determine that supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids or regular consumption of fish are effective treatments for rheumatoid arthritis.[139][140][141][142]

- Herbal

- The American College of Rheumatology states that no herbal medicines have health claims supported by high-quality evidence and thus they do not recommend their use.[143] There is no scientific basis to suggest that herbal supplements advertised as "natural" are safer for use than conventional medications as both are chemicals. Herbal medications, although labelled "natural", may be toxic or fatal if consumed.[143]

Due to the false belief that herbal supplements are always safe, there is sometimes a hesitancy to report their use which may increase the risk of adverse reaction.[10]

The following are under investigation for treatments for RA, based on preliminary promising results (not recommended for clinical use yet): boswellic acid,[144] curcumin,[145] devil's claw,[146][147] Euonymus alatus,[148] and thunder god vine (Tripterygium wilfordii).[149] NCCIH has noted that, "In particular, the herb thunder god vine (Tripterygium wilfordii) can have serious side effects."[11]

There is conflicting evidence on the role of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for treatment of anemia in persons with rheumatoid arthritis.[150]

Pregnancy

More than 75% of women with rheumatoid arthritis have symptoms improve during pregnancy but might have symptoms worsen after delivery.[22] Methotrexate and leflunomide are teratogenic (harmful to foetus) and not used in pregnancy. It is recommended women of childbearing age should use contraceptives to avoid pregnancy and to discontinue its use if pregnancy is planned.[75][92] Low dose of prednisolone, hydroxychloroquine and sulfasalazine are considered safe in pregnant persons with rheumatoid arthritis. Prednisolone should be used with caution as the side effects include infections and fractures.[151]

Vaccinations

People with RA have an increased risk of infections and mortality and recommended vaccinations can reduce these risks.[152] The inactivated influenza vaccine should be received annually.[153] The pneumococcal vaccine should be administered twice for people under the age 65 and once for those over 65.[154] Lastly, the live-attenuated zoster vaccine should be administered once after the age 60, but is not recommended in people on a tumor necrosis factor alpha blocker.[155]

Prognosis

The course of the disease varies greatly. Some people have mild short-term symptoms, but in most the disease is progressive for life. Around 25% will have subcutaneous nodules (known as rheumatoid nodules);[157] this is associated with a poor prognosis.[158]

Prognostic factors

Poor prognostic factors include,

- Persistent synovitis

- Early erosive disease

- Extra-articular findings (including subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules)

- Positive serum RF findings

- Positive serum anti-CCP autoantibodies

- Carriership of HLA-DR4 "Shared Epitope" alleles

- Family history of RA

- Poor functional status

- Socioeconomic factors

- Elevated acute phase response (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], C-reactive protein [CRP])

- Increased clinical severity.

Mortality

RA reduces lifespan on average from three to twelve years.[75] Young age at onset, long disease duration, the presence of other health problems, and characteristics of severe RA—such as poor functional ability or overall health status, a lot of joint damage on x-rays, the need for hospitalisation or involvement of organs other than the joints—have been shown to associate with higher mortality.[159] Positive responses to treatment may indicate a better prognosis. A 2005 study by the Mayo Clinic noted that RA sufferers suffer a doubled risk of heart disease,[160] independent of other risk factors such as diabetes, alcohol abuse, and elevated cholesterol, blood pressure and body mass index. The mechanism by which RA causes this increased risk remains unknown; the presence of chronic inflammation has been proposed as a contributing factor.[161] It is possible that the use of new biologic drug therapies extend the lifespan of people with RA and reduce the risk and progression of atherosclerosis.[162] This is based on cohort and registry studies, and still remains hypothetical. It is still uncertain whether biologics improve vascular function in RA or not. There was an increase in total cholesterol and HDLc levels and no improvement of the atherogenic index.[163]

Epidemiology

RA affects between 0.5 and 1% of adults in the developed world with between 5 and 50 per 100,000 people newly developing the condition each year.[3] In 2010 it resulted in about 49,000 deaths globally.[164]

Onset is uncommon under the age of 15 and from then on the incidence rises with age until the age of 80. Women are affected three to five times as often as men.[22]

The age at which the disease most commonly starts is in women between 40 and 50 years of age, and for men somewhat later.[165] RA is a chronic disease, and although rarely, a spontaneous remission may occur, the natural course is almost invariably one of the persistent symptoms, waxing and waning in intensity, and a progressive deterioration of joint structures leading to deformations and disability.

There is an association between periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), hypothesised to lead to enhanced generation of RA-related autoantibodies. Oral bacteria that invade the blood may also contribute to chronic inflammatory responses and generation of autoantibodies.[166]

History

The first known traces of arthritis date back at least as far as 4500 BC. A text dated 123 AD first describes symptoms very similar to RA.[citation needed] It was noted in skeletal remains of Native Americans found in Tennessee.[167] In Europe, the disease is vanishingly rare before the 17th century.[168] The first recognized description of RA in modern medicine was in 1800 by the French physician Dr Augustin Jacob Landré-Beauvais (1772–1840) who was based in the famed Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris.[14] The name "rheumatoid arthritis" itself was coined in 1859 by British rheumatologist Dr Alfred Baring Garrod.[169]

An anomaly has been noticed from the investigation of Pre-Columbian bones. The bones from the Tennessee site show no signs of tuberculosis even though it was prevalent at the time throughout the Americas.[170]

The art of Peter Paul Rubens may possibly depict the effects of RA. In his later paintings, his rendered hands show, in the opinion of some physicians, increasing deformity consistent with the symptoms of the disease.[171][172] RA appears to some to have been depicted in 16th-century paintings.[173] However, it is generally recognized in art historical circles that the painting of hands in the 16th and 17th century followed certain stylized conventions, most clearly seen in the Mannerist movement. It was conventional, for instance, to show the upheld right hand of Christ in what now appears a deformed posture. These conventions are easily misinterpreted as portrayals of disease.

Historic treatments for RA have also included: rest, ice, compression and elevation, apple diet, nutmeg, some light exercise every now and then, nettles, bee venom, copper bracelets, rhubarb diet, extractions of teeth, fasting, honey, vitamins, insulin, magnets, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).[174]

Etymology

Rheumatoid arthritis is derived from the Greek word ῥεύμα-rheuma (nom.), ῥεύματος-rheumatos (gen.) ("flow, current"). The suffix -oid ("resembling") gives the translation as joint inflammation that resembles rheumatic fever. Rhuma which means watery discharge might refer to the fact that the joints are swollen or that the disease may be made worse by wet weather.[15]

Research

Meta-analysis found an association between periodontal disease and RA, but the mechanism of this association remains unclear.[175] Two bacterial species associated with periodontitis are implicated as mediators of protein citrullination in the gums of people with RA.[3]

Vitamin D deficiency is more common in people with rheumatoid arthritis than in the general population.[176][177] However, whether vitamin D deficiency is a cause or a consequence of the disease remains unclear.[178] One meta-analysis found that vitamin D levels are low in people with rheumatoid arthritis and that vitamin D status correlates inversely with prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis, suggesting that vitamin D deficiency is associated with susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis.[179]

The fibroblast-like synoviocytes have a prominent role in the pathogenic processes of the rheumatic joints, and therapies that target these cells are emerging as promising therapeutic tools, raising hope for future applications in rheumatoid arthritis.[19]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Handout on Health: Rheumatoid Arthritis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. August 2014. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Majithia V, Geraci SA (November 2007). "Rheumatoid arthritis: diagnosis and management". The American Journal of Medicine. 120 (11): 936–9. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.04.005. PMID 17976416.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB (October 2016). "Rheumatoid arthritis" (PDF). Lancet. 388 (10055): 2023–2038. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30173-8. PMID 27156434. S2CID 37973054.

- ^ Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ a b c d "Rheumatoid arthritis in adults: management: recommendations: Guidance and guidelines". NICE. December 2015. Archived from the original on 2017-04-16.

- ^ a b c d Rausch Osthoff AK, Juhl CB, Knittle K, Dagfinrud H, Hurkmans E, Braun J, et al. (2018-12-04). "Effects of exercise and physical activity promotion: meta-analysis informing the 2018 EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis and hip/knee osteoarthritis". RMD Open. 4 (2): e000713. doi:10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000713. PMC 6307596. PMID 30622734.

- ^ a b c Park Y, Chang M (January 2016). "Effects of rehabilitation for pain relief in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review". Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 28 (1): 304–8. doi:10.1589/jpts.28.304. PMC 4756025. PMID 26957779.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, Akl EA, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, Vaysbrot E, McNaughton C, Osani M, Shmerling RH, Curtis JR, Furst DE, Parks D, Kavanaugh A, O'Dell J, King C, Leong A, Matteson EL, Schousboe JT, Drevlow B, Ginsberg S, Grober J, St Clair EW, Tindall E, Miller AS, McAlindon T (January 2016). "2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis". Arthritis & Rheumatology. 68 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1002/art.39480. PMID 26545940.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Singh JA, Wells GA, Christensen R, Tanjong Ghogomu E, Maxwell L, Macdonald JK, Filippini G, Skoetz N, Francis D, Lopes LC, Guyatt GH, Schmitt J, La Mantia L, Weberschock T, Roos JF, Siebert H, Hershan S, Lunn MP, Tugwell P, Buchbinder R (February 2011). "Adverse effects of biologics: a network meta-analysis and Cochrane overview". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD008794. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008794.pub2. PMC 7173749. PMID 21328309.

- ^ a b c Efthimiou P, Kukar M (March 2010). "Complementary and alternative medicine use in rheumatoid arthritis: proposed mechanism of action and efficacy of commonly used modalities". Rheumatology International. 30 (5): 571–86. doi:10.1007/s00296-009-1206-y. PMID 19876631. S2CID 21179821.

- ^ a b c "Rheumatoid Arthritis and Complementary Health Approaches". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. January 2006. Archived from the original on July 5, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- ^ Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ GBD 2013 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

{{cite journal}}:|author1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Landré-Beauvais AJ (1800). La goutte asthénique primitive (doctoral thesis). Paris. reproduced in Landré-Beauvais AJ (March 2001). "The first description of rheumatoid arthritis. Unabridged text of the doctoral dissertation presented in 1800". Joint, Bone, Spine. 68 (2): 130–43. doi:10.1016/S1297-319X(00)00247-5. PMID 11324929.

- ^ a b Paget, Stephen A.; Lockshin, Michael D.; Loebl, Suzanne (2002). The Hospital for Special Surgery Rheumatoid Arthritis Handbook Everything You Need to Know. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 32. ISBN 9780471223344. Archived from the original on 2017-02-22.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Turesson C, O'Fallon WM, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE, Matteson EL (August 2003). "Extra-articular disease manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis: incidence trends and risk factors over 46 years". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 62 (8): 722–7. doi:10.1136/ard.62.8.722. PMC 1754626. PMID 12860726.

- ^ Cutolo M, Kitas GD, van Riel PL (February 2014). "Burden of disease in treated rheumatoid arthritis patients: going beyond the joint". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 43 (4): 479–88. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.08.004. PMID 24080116.

- ^ a b c d Walker, Brian R.; Colledge, Nicki R.; Ralston, Stuart H.; Penman, Ian D., eds. (2014). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (22nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-5035-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Nygaard G, Firestein GS (June 2020). "Restoring synovial homeostasis in rheumatoid arthritis by targeting fibroblast-like synoviocytes". Nature Reviews. Rheumatology. 16 (6): 316–333. doi:10.1038/s41584-020-0413-5. PMID 32393826. S2CID 218573182.

- ^ Suresh E (September 2004). "Diagnosis of early rheumatoid arthritis: what the non-specialist needs to know". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 97 (9): 421–4. doi:10.1258/jrsm.97.9.421. PMC 1079582. PMID 15340020.

- ^ Gaffo A, Saag KG, Curtis JR (December 2006). "Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 63 (24): 2451–65. doi:10.2146/ajhp050514. PMC 5164397. PMID 17158693.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Shah, Ankur (2012). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (18th ed.). United States: McGraw Hill. p. 2738. ISBN 978-0-07174889-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Turesson C (May 2013). "Extra-articular rheumatoid arthritis". Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 25 (3): 360–6. doi:10.1097/bor.0b013e32835f693f. PMID 23425964.

- ^ Ziff M (June 1990). "The rheumatoid nodule". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 33 (6): 761–7. doi:10.1002/art.1780330601. PMID 2194460.

- ^ Genta MS, Genta RM, Gabay C (October 2006). "Systemic rheumatoid vasculitis: a review". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 36 (2): 88–98. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.04.006. PMID 17023257.

- ^ a b Khan Mohammad Beigi, Pooya (2018). Alopecia Areata. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-72134-7. ISBN 978-3-319-72133-0. S2CID 46954629.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Kim EJ, Collard HR, King TE (November 2009). "Rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: the relevance of histopathologic and radiographic pattern". Chest. 136 (5): 1397–1405. doi:10.1378/chest.09-0444. PMC 2818853. PMID 19892679.

- ^ Balbir-Gurman A, Yigla M, Nahir AM, Braun-Moscovici Y (June 2006). "Rheumatoid pleural effusion". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 35 (6): 368–78. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.03.002. PMID 16765714.

- ^ Wolfe F, Mitchell DM, Sibley JT, Fries JF, Bloch DA, Williams CA, Spitz PW, Haga M, Kleinheksel SM, Cathey MA (April 1994). "The mortality of rheumatoid arthritis". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 37 (4): 481–94. doi:10.1002/art.1780370408. PMID 8147925.

- ^ Aviña-Zubieta JA, Choi HK, Sadatsafavi M, Etminan M, Esdaile JM, Lacaille D (December 2008). "Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 59 (12): 1690–7. doi:10.1002/art.24092. PMID 19035419.

- ^ Alenghat FJ (February 2016). "The Prevalence of Atherosclerosis in Those with Inflammatory Connective Tissue Disease by Race, Age, and Traditional Risk Factors". Scientific Reports. 6: 20303. Bibcode:2016NatSR...620303A. doi:10.1038/srep20303. PMC 4740809. PMID 26842423.

- ^ a b Gupta A, Fomberstein B (2009). "Evaluating cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis". Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. 26 (8): 481–94. Archived from the original on 2012-07-23.

- ^ de Groot K (August 2007). "[Renal manifestations in rheumatic diseases]". Der Internist. 48 (8): 779–85. doi:10.1007/s00108-007-1887-9. PMID 17571244.

- ^ Schonberg S, Stokkermans TJ (January 2020). "Episcleritis". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30521217.

- ^ a b Selmi C, De Santis M, Gershwin ME (June 2011). "Liver involvement in subjects with rheumatic disease". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 13 (3): 226. doi:10.1186/ar3319. PMC 3218873. PMID 21722332.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Wasserman BR, Moskovich R, Razi AE (2011). "Rheumatoid arthritis of the cervical spine--clinical considerations" (PDF). Bulletin of the NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases. 69 (2): 136–48. PMID 22035393.

- ^ Baecklund E, Iliadou A, Askling J, Ekbom A, Backlin C, Granath F, Catrina AI, Rosenquist R, Feltelius N, Sundström C, Klareskog L (March 2006). "Association of chronic inflammation, not its treatment, with increased lymphoma risk in rheumatoid arthritis". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 54 (3): 692–701. doi:10.1002/art.21675. PMID 16508929.

- ^ Franklin J, Lunt M, Bunn D, Symmons D, Silman A (May 2006). "Incidence of lymphoma in a large primary care derived cohort of cases of inflammatory polyarthritis". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 65 (5): 617–22. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.044784. PMC 1798140. PMID 16249224.

- ^ Assassi S (January 2016). "Rheumatoid arthritis, TNF inhibitors, and non-melanoma skin cancer". BMJ. 352: i472. doi:10.1136/bmj.i472. PMID 26822198.

- ^ de Pablo P, Chapple IL, Buckley CD, Dietrich T (April 2009). "Periodontitis in systemic rheumatic diseases". Nature Reviews. Rheumatology. 5 (4): 218–24. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2009.28. PMID 19337286. S2CID 7173008.

- ^ a b Doherty M, Lanyon P, Ralston SH. Musculosketal Disorders-Davidson's Principle of Internal Medicine (20th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 1100–1106.

- ^ Firestein GS, McInnes IB (February 2017). "Immunopathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis". Immunity. 46 (2): 183–196. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2017.02.006. PMC 5385708. PMID 28228278.(subscription required)

- ^ a b Sugiyama D, Nishimura K, Tamaki K, Tsuji G, Nakazawa T, Morinobu A, Kumagai S (January 2010). "Impact of smoking as a risk factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies" (PDF). Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 69 (1): 70–81. doi:10.1136/ard.2008.096487. PMID 19174392. S2CID 11303269.(subscription required)

- ^ Liao KP, Alfredsson L, Karlson EW (May 2009). "Environmental influences on risk for rheumatoid arthritis". Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 21 (3): 279–83. doi:10.1097/BOR.0b013e32832a2e16. PMC 2898190. PMID 19318947.(subscription required)

- ^ Pollard KM (11 March 2016). "Silica, Silicosis, and Autoimmunity". Frontiers in Immunology. 7: 97. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2016.00097. PMC 4786551. PMID 27014276.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Edwards JC, Cambridge G, Abrahams VM (June 1999). "Do self-perpetuating B lymphocytes drive human autoimmune disease?". Immunology. 97 (2): 188–96. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00772.x. PMC 2326840. PMID 10447731.(subscription required)

- ^ Padyukov L, Silva C, Stolt P, Alfredsson L, Klareskog L (October 2004). "A gene-environment interaction between smoking and shared epitope genes in HLA-DR provides a high risk of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 50 (10): 3085–92. doi:10.1002/art.20553. PMID 15476204.(subscription required)

- ^ Hua C, Daien CI, Combe B, Landewe R (2017). "Diagnosis, prognosis and classification of early arthritis: results of a systematic review informing the 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of early arthritis". RMD Open. 3 (1): e000406. doi:10.1136/rmdopen-2016-000406. PMC 5237764. PMID 28155923.

- ^ a b Maverakis E, Kim K, Shimoda M, Gershwin ME, Patel F, Wilken R, Raychaudhuri S, Ruhaak LR, Lebrilla CB (February 2015). "Glycans in the immune system and The Altered Glycan Theory of Autoimmunity: a critical review". Journal of Autoimmunity. 57 (6): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2014.12.002. PMC 4340844. PMID 25578468.(subscription required)

- ^ Boldt AB, Goeldner I, de Messias-Reason IJ (2012). Relevance of the lectin pathway of complement in rheumatic diseases. Advances in Clinical Chemistry. Vol. 56. pp. 105–53. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-394317-0.00012-1. ISBN 9780123943170. PMID 22397030.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)(subscription required) - ^ Elshabrawy HA, Chen Z, Volin MV, Ravella S, Virupannavar S, Shahrara S (October 2015). "The pathogenic role of angiogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis". Angiogenesis. 18 (4): 433–48. doi:10.1007/s10456-015-9477-2. PMC 4879881. PMID 26198292.

- ^ Abildtrup M, Kingsley GH, Scott DL (May 2015). "Calprotectin as a biomarker for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review". The Journal of Rheumatology. 42 (5): 760–70. doi:10.3899/jrheum.140628. PMID 25729036. S2CID 43537545.

- ^ Chiu YG, Ritchlin CT (January 2017). "Denosumab: targeting the RANKL pathway to treat rheumatoid arthritis". Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 17 (1): 119–128. doi:10.1080/14712598.2017.1263614. PMC 5794005. PMID 27871200.(subscription required)

- ^ Ideguchi H, Ohno S, Hattori H, Senuma A, Ishigatsubo Y (2006). "Bone erosions in rheumatoid arthritis can be repaired through reduction in disease activity with conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 8 (3): R76. doi:10.1186/ar1943. PMC 1526642. PMID 16646983.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Takase-Minegishi K, Horita N, Kobayashi K, Yoshimi R, Kirino Y, Ohno S, Kaneko T, Nakajima H, Wakefield RJ, Emery P (January 2018). "Diagnostic test accuracy of ultrasound for synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis". Rheumatology. 57 (1): 49–58. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kex036. PMID 28340066.

- ^ Schueller-Weidekamm, Claudia (Apr 29, 2010). "Modern ultrasound methods yield stronger arthritis work-up". Diagnostic Imaging. 32.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Westwood OM, Nelson PN, Hay FC (April 2006). "Rheumatoid factors: what's new?". Rheumatology. 45 (4): 379–85. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kei228. PMID 16418203.(subscription required)

- ^ Nishimura K, Sugiyama D, Kogata Y, Tsuji G, Nakazawa T, Kawano S, Saigo K, Morinobu A, Koshiba M, Kuntz KM, Kamae I, Kumagai S (June 2007). "Meta-analysis: diagnostic accuracy of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody and rheumatoid factor for rheumatoid arthritis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 146 (11): 797–808. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-146-11-200706050-00008. PMID 17548411. S2CID 6640507.(subscription required)

- ^ van Venrooij WJ, van Beers JJ, Pruijn GJ (June 2011). "Anti-CCP antibodies: the past, the present and the future". Nature Reviews. Rheumatology. 7 (7): 391–8. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2011.76. PMID 21647203. S2CID 11858403.(subscription required)

- ^ Renger F, Bang H, Fredenhagen G, et al. "Anti-MCV Antibody Test for the Diagnosis of Rheumatoid Arthritis Using a POCT-Immunoassay". American College of Rheumatology, 2008 Annual Scientific Meeting, Poster Presentation. Archived from the original on 2010-05-27.

- ^ Luime JJ, Colin EM, Hazes JM, Lubberts E (February 2010). "Does anti-mutated citrullinated vimentin have additional value as a serological marker in the diagnostic and prognostic investigation of patients with rheumatoid arthritis? A systematic review". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 69 (2): 337–44. doi:10.1136/ard.2008.103283. PMID 19289382. S2CID 22283893.(subscription required)

- ^ a b Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO, Birnbaum NS, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP, Cohen MD, Combe B, Costenbader KH, Dougados M, Emery P, Ferraccioli G, Hazes JM, Hobbs K, Huizinga TW, Kavanaugh A, Kay J, Kvien TK, Laing T, Mease P, Ménard HA, Moreland LW, Naden RL, Pincus T, Smolen JS, Stanislawska-Biernat E, Symmons D, Tak PP, Upchurch KS, Vencovsky J, Wolfe F, Hawker G (September 2010). "2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative" (PDF). Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 69 (9): 1580–8. doi:10.1136/ard.2010.138461. PMID 20699241. S2CID 1191830.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, Healey LA, Kaplan SR, Liang MH, Luthra HS (March 1988). "The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 31 (3): 315–24. doi:10.1002/art.1780310302. PMID 3358796.

- ^ Flynn JA, Choi MJ, Wooster DL (2013). Oxford American Handbook of Clinical Medicine. US: OUP. p. 400. ISBN 978-0-19-991494-4.

- ^ Seidman AJ, Limaiem F (2019). "Synovial Fluid Analysis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30725799. Retrieved 2019-12-19.

- ^ a b Berkow R, ed. (1992). The Merck Manual (16th ed.). Merck Publishing Group. pp. 1307–08. ISBN 978-0-911910-16-2.(subscription required)

- ^ a b Prevoo ML, van 't Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL (January 1995). "Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 38 (1): 44–8. doi:10.1002/art.1780380107. hdl:2066/20651. PMID 7818570.(subscription required)

- ^ Kelly, Janis (22 February 2005) DAS28 not always a reliable indicator of treatment effect in RA Archived 2011-02-25 at the Wayback Machine, Medscape Medical News.

- ^ Uribe L, Cerón C, Amariles P, Llano JF, Restrepo M, Montoya N, et al. (July–September 2016). "Correlación entre la actividad clínica por DAS-28 y ecografía en pacientes con artritis reumatoide" [Correlation between clinical activity measured by DAS-28 and ultrasound in patients with rheumatoid arthritis]. Revista Colombiana de Reumatología (in Spanish). 23 (3): 159–169. doi:10.1016/j.rcreu.2016.05.002.

- ^ Yazici Y, Simsek I (January 2013). "Tools for monitoring remission in rheumatoid arthritis: any will do, let's just pick one and start measuring". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 15 (1): 104. doi:10.1186/ar4139. PMC 3672754. PMID 23374997.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)(subscription required) - ^ Bruce B, Fries JF (June 2003). "The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire: dimensions and practical applications". Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 1: 20. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-1-20. PMC 165587. PMID 12831398.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)(subscription required) - ^ Spriggs, Brenda B (2014-09-04). "Rheumatoid Arthritis Prevention". Healthline Networks. Archived from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, Anuntiyo J, Finney C, Curtis JR, et al. (June 2008). "American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 59 (6): 762–84. doi:10.1002/art.23721. PMID 18512708.

- ^ Donahue KE, Schulman ER, Gartlehner G, Jonas BL, Coker-Schwimmer E, Patel SV, et al. (October 2019). "Comparative Effectiveness of Combining MTX with Biologic Drug Therapy Versus Either MTX or Biologics Alone for Early Rheumatoid Arthritis in Adults: a Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 34 (10): 2232–2245. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05230-0. PMC 6816735. PMID 31388915.

- ^ a b c Wasserman AM (December 2011). "Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis". American Family Physician. 84 (11): 1245–52. PMID 22150658.

- ^ Richards BL, Whittle SL, Buchbinder R (January 2012). Richards BL (ed.). "Muscle relaxants for pain management in rheumatoid arthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD008922. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008922.pub2. PMID 22258993.

- ^ Hurkmans E, van der Giesen FJ, Vliet Vlieland TP, Schoones J, Van den Ende EC (October 2009). Hurkmans E (ed.). "Dynamic exercise programs (aerobic capacity and/or muscle strength training) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD006853. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006853.pub2. PMC 6769170. PMID 19821388.

- ^ Cramp F, Hewlett S, Almeida C, Kirwan JR, Choy EH, Chalder T, et al. (August 2013). "Non-pharmacological interventions for fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD008322. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008322.pub2. PMID 23975674.

- ^ Williams MA, Srikesavan C, Heine PJ, Bruce J, Brosseau L, Hoxey-Thomas N, Lamb SE (July 2018). "Exercise for rheumatoid arthritis of the hand". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7: CD003832. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003832.pub3. PMC 6513509. PMID 30063798.

- ^ Rausch Osthoff AK, Juhl CB, Knittle K, Dagfinrud H, Hurkmans E, Braun J, et al. (December 2018). "Effects of exercise and physical activity promotion: meta-analysis informing the 2018 EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis and hip/knee osteoarthritis". RMD Open. 4 (2): e000713. doi:10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000713. PMC 6307596. PMID 30622734.

- ^ Hagen KB, Byfuglien MG, Falzon L, Olsen SU, Smedslund G (January 2009). Hagen KB (ed.). "Dietary interventions for rheumatoid arthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD006400. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006400.pub2. PMID 19160281.

- ^ Steultjens EM, Dekker J, Bouter LM, van Schaardenburg D, van Kuyk MA, van den Ende CH (2004). "Occupational therapy for rheumatoid arthritis" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD003114. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003114.pub2. hdl:2066/58846. PMC 7017227. PMID 14974005.

- ^ Robinson V, Brosseau L, Casimiro L, Judd M, Shea B, Wells G, Tugwell P (2002-04-22). "Thermotherapy for treating rheumatoid arthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD002826. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd002826. PMC 6991938. PMID 12076454.

- ^ Riemsma RP, Kirwan JR, Taal E, Rasker JJ (2003-04-22). "Patient education for adults with rheumatoid arthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009 (2): CD003688. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003688. PMID 12804484.

- ^ a b Egan M, Brosseau L, Farmer M, Ouimet MA, Rees S, Wells G, Tugwell P (2001-10-23). "Splints/orthoses in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004018. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004018. PMID 12535502.

- ^ Isaacs D (2010-07-07). "Infectious risks associated with biologics". Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 764: 151–8. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008331.pub2. PMID 23654064.

- ^ Suarez-Almazor ME, Belseck E, Shea B, Homik J, Wells G, Tugwell P (2000). "Antimalarials for treating rheumatoid arthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD000959. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000959. PMID 11034691.

- ^ Osiri M, Shea B, Robinson V, Suarez-Almazor M, Strand V, Tugwell P, Wells G (2003). "Leflunomide for treating rheumatoid arthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD002047. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002047. PMID 12535423.

- ^ Suarez-Almazor ME, Belseck E, Shea B, Wells G, Tugwell P (1998-04-27). "Sulfasalazine for rheumatoid arthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD000958. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd000958. PMC 7047550. PMID 10796400.

- ^ Wells G, Haguenauer D, Shea B, Suarez-Almazor ME, Welch VA, Tugwell P (2000). "Cyclosporine for rheumatoid arthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD001083. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001083. PMID 10796412.

- ^ Katchamart W, Trudeau J, Phumethum V, Bombardier C (April 2010). "Methotrexate monotherapy versus methotrexate combination therapy with non-biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs for rheumatoid arthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD008495. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008495. PMID 20393970.

- ^ a b c DiPiro, Joseph T., Robert L. Talbert, Gary C. Yee, Gary R. Matzke, Barbara G. Wells, and L. Michael Posey (2008) Pharmacotherapy: a pathophysiologic approach. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-147899-1.

- ^ Singh JA, Hossain A, Mudano AS, Tanjong Ghogomu E, Suarez-Almazor ME, Buchbinder R, et al. (May 2017). "Biologics or tofacitinib for people with rheumatoid arthritis naive to methotrexate: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5: CD012657. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012657. PMC 6481641. PMID 28481462.