DShK

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2010) |

The DShK 1938 (ДШК, for Дегтярёва-Шпагина Крупнокалиберный, Degtyaryova-Shpagina Krupnokaliberny, "Degtyaryov-Shpagin Large-Calibre") is a Soviet heavy machine gun with a V-shaped "butterfly" trigger, firing the 12.7×108mm cartridge. The weapon was also used as a heavy infantry machine gun, in which case it was frequently deployed with a two-wheeled mounting and a single-sheet armour-plate shield. It took its name from the weapons designers Vasily Degtyaryov, who designed the original weapon, and Georgi Shpagin, who improved the cartridge feed mechanism. It is sometimes nicknamed Dushka (a dear or beloved person) in Russian-speaking countries, from the abbreviation.[14]

History

The requirement for a heavy machine gun appeared in 1929. The first such gun, the Degtyaryov, Krupnokalibernyi (DK, Degtyaryov, large calibre), was built in 1930, and this gun was produced in small quantities from 1933 to 1935.

The gun was fed from a drum magazine of thirty rounds, and had a poor rate of fire. Shpagin developed a belt feed mechanism to fit to the DK giving rise, in 1938, to the adoption of the gun as the DShK 1938. This became the standard Soviet heavy machine gun in World War II.

Like its U.S. equivalent, the M2 Browning, the DShK 1938 was used in several roles. As an anti-aircraft weapon it was mounted on pintle and tripod mounts, and on a triple mount on the GAZ-AA truck. Late in the war, it was mounted on the cupolas of IS-2 tanks and ISU-152 self-propelled guns. As an infantry heavy support weapon it used a two-wheeled trolley which unfolded into a tripod for anti-aircraft use, similar to the mount developed by Vladimirov for the 1910 Maxim gun.[15] It was also mounted in vehicle turrets, for example, in the T-40 light amphibious tank.

In 1946, the DShK 1938/46 or DShKM (M for modernized) version was introduced.

In addition to the Soviet Union and Russia, the DShK has been manufactured under license by a number of countries, including the People's Republic of China (Type 54), Pakistan, and Romania. Currently, it has been mostly replaced in favour of the more modern NSV and Kord designs. Nevertheless, the DShK is still one of the most widely used heavy machine guns.

In June 1988, during the conflict in Northern Ireland known as "the Troubles", a British Army Westland Lynx helicopter was hit 15 times by two Provisional IRA DShKs smuggled in from Libya, and forced to crash-land near Cashel Lough Upper, south County Armagh.[16]

DShKs were also used in 2004, against British troops in Al-Amarah, Iraq.[17]

In the 2012 Syrian civil war, the Syrian government said rebels used the gun mounted on cars. It claimed to have destroyed, on the same day, 40 such cars on a highway in Aleppo and six in Dael.[18]

It is often claimed that the DShK could fire US/NATO .50-caliber ammunition, but the DShK can not fire 12.7x99mm ammunition but instead fires 12.7x108mm ammunition. Neither round is interchangeable, with their case length and head (cartridge base) dimensions completely different and will not chamber or function in the other weapon. The Russian ammunition is 12.7×108mm and the US is 12.7×99mm. The myth began in US weapons intelligence manuals referring to the DShK as being "12.7mm (.51-caliber)" and the assumption made that this was intentional to accommodate interchangeable ammunition.

Variants

- DShKM: modernized version

- Type 54: Chinese unlicensed production. Also produced in Pakistan with a Chinese license.[19]

- HMG PK-16, a Pakistani variant

Users

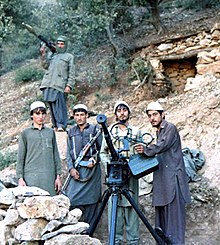

Afghanistan[20]

Afghanistan[20] Albania[20] "DShkM" locally produced from a Chinese copy

Albania[20] "DShkM" locally produced from a Chinese copy Algeria[20]

Algeria[20] Angola[20]

Angola[20] Armenia[20]

Armenia[20] Azerbaijan[20]

Azerbaijan[20] Bangladesh[20] Type 54.

Bangladesh[20] Type 54. Belarus[20]

Belarus[20] Bulgaria[20]

Bulgaria[20] Burkina Faso[10]

Burkina Faso[10] Burundi[21]

Burundi[21] Cambodia[20]

Cambodia[20] Cameroon[22]

Cameroon[22] Cape Verde[20]

Cape Verde[20] Central African Republic[20]

Central African Republic[20] Chad[20]

Chad[20] Chile[23]

Chile[23] China: Produced DShKM variant.[24]

China: Produced DShKM variant.[24] Congo-Brazzaville[20]

Congo-Brazzaville[20] Congo-Kinshasa[20][25]

Congo-Kinshasa[20][25] Cuba[20]

Cuba[20] Cyprus[20]

Cyprus[20] Czechoslovakia: Produced DShKM variant TK vz. 53 which included a four barrelled version.[24] (former user)

Czechoslovakia: Produced DShKM variant TK vz. 53 which included a four barrelled version.[24] (former user) Czech Republic[20]

Czech Republic[20] Egypt[20]

Egypt[20] Equatorial Guinea[20]

Equatorial Guinea[20] Eritrea[20]

Eritrea[20] Estonia[26]

Estonia[26] Ethiopia[20]

Ethiopia[20] Finland[20]

Finland[20] Georgia[20]

Georgia[20] Ghana[20]

Ghana[20] Guinea[20]

Guinea[20] Guinea-Bissau[20]

Guinea-Bissau[20] Hungary[20]

Hungary[20] Indonesia[20]

Indonesia[20] Iran: Manufactured DShKM variant named MGD 12.7.[27][28]

Iran: Manufactured DShKM variant named MGD 12.7.[27][28] Iraq[20] called the "Doshka" by Iraqis

Iraq[20] called the "Doshka" by Iraqis

Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant

Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant Israel[20]

Israel[20] India Captured during Kargil War[citation needed]

India Captured during Kargil War[citation needed] Ivory Coast[30]

Ivory Coast[30] Kazakhstan[20]

Kazakhstan[20] Kenya[31]

Kenya[31] Kosovo

Kosovo Kyrgyzstan[20]

Kyrgyzstan[20] Laos[20]

Laos[20] Liberia[32]

Liberia[32] Libya[20]

Libya[20] Macedonia[20]

Macedonia[20] Madagascar[20]

Madagascar[20] Mali[20] – Armed and Security Forces of Mali

Mali[20] – Armed and Security Forces of Mali Malta[20]

Malta[20] Mongolia[33]

Mongolia[33] Mozambique[20]

Mozambique[20] Nicaragua[20]

Nicaragua[20] Niger[citation needed]

Niger[citation needed] Nigeria[20]

Nigeria[20] North Korea[20]

North Korea[20] North Vietnam[24] (former user)

North Vietnam[24] (former user) Pakistan: Used by the Pakistan Army. DShKM variant produced locally.[34][35]

Pakistan: Used by the Pakistan Army. DShKM variant produced locally.[34][35] Peru[20]

Peru[20] Poland[36]

Poland[36] Palestine

Palestine Romania Produce locally[37] (still used with TR-85 tanks)

Romania Produce locally[37] (still used with TR-85 tanks) Russian Federation[20]

Russian Federation[20] Rwanda: Used by Rwandan Peacekeepers in Darfur.[citation needed]

Rwanda: Used by Rwandan Peacekeepers in Darfur.[citation needed] Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia Serbia[20]

Serbia[20] Seychelles[20]

Seychelles[20] Sierra Leone[20]

Sierra Leone[20] Slovakia[20]

Slovakia[20] Somalia[20]

Somalia[20] Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic[1]

Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic[1] South Sudan[38]

South Sudan[38] Soviet Union[24]

Soviet Union[24] Sudan[citation needed]

Sudan[citation needed] Syria[20]

Syria[20] Sri Lanka: Used by Tamil Tigers. (former user)

Sri Lanka: Used by Tamil Tigers. (former user) Tanzania[20]

Tanzania[20] Togo[20]

Togo[20] Turkey[39]

Turkey[39] Turkmenistan[20]

Turkmenistan[20] Uganda[20]

Uganda[20] Ukraine[20]

Ukraine[20] Vietnam[20]

Vietnam[20] Yemen[20]

Yemen[20] Yugoslavia: Manufactured DShKM variant.[27] (former user)

Yugoslavia: Manufactured DShKM variant.[27] (former user) Zambia[20]

Zambia[20] Zimbabwe[20]

Zimbabwe[20]

Anti-aircraft sight

Many DShKs intended for the close anti-aircraft role were fitted with a simple mechanical sighting system that helped the gunner properly account for "lead" in order to hit fast-moving targets.

The system consisted of two circular disks mounted side-by-side in a common framework. On the right, in front of the gunner, was a large "spider" sight that contained a line of small metal rings running from the center to the outer edge. On the left, in front of the loader, was a smaller disk with several parallel metal wires. In some examples, the sight was installed with the loader's sight on the right.

To use the sight, the loader/observer would spin his disk so the wires were parallel to the target's direction of travel. A shaft running between the two turned the gunner's sight to the same angle. The gunner would then sight through one of the metal rings based on the estimated range and speed.

Gallery

-

A soldier with the Ukrainian Land Forces fires a DShKM

-

DShKM TR-85M1

-

DShKM URO VAMTAC

-

DShKM T-55

-

DShK M1938

-

DShKM anti-aircraft machine gun on a T-55 tank loader's roof hatch

-

The M53 is an anti-aircraft mounting of four 12.7 mm heavy machine guns vz. 38/46 (Czech copy of Soviet DShKM)

See also

References

- ^ a b Francesco Palmas (2012). "Il contenzioso del sahara occidentale fra passato e presente" (PDF). Informazioni della Difesa (in Italian). No. 4. pp. 50–59. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- ^ Fitzsimmons, Scott (November 2012). "Executive Outcomes Defeats UNITA". Mercenaries in Asymmetric Conflicts. Cambridge University Press. p. 217. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139208727.006. ISBN 9781107026919.

- ^ Neville, Leigh (19 Apr 2018). Technicals: Non-Standard Tactical Vehicles from the Great Toyota War to modern Special Forces. New Vanguard 257. Osprey Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 9781472822512. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Neville 2018, p. 16.

- ^ a b Neville 2018, p. 24.

- ^ Small Arms Survey (2005). "Sourcing the Tools of War: Small Arms Supplies to Conflict Zones" (PDF). Small Arms Survey 2005: Weapons at War. Oxford University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-19-928085-8. Archived from the original on 2018-08-30. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- ^ Neville 2018, p. 30.

- ^ Neville 2018, p. 26.

- ^ Neville 2018, p. 35.

- ^ a b Cherisey, Erwan de (July 2019). "El batallón de infantería "Badenya" de Burkina Faso en Mali - Noticias Defensa En abierto". Revista Defensa (in Spanish) (495–496).

- ^ Neville 2018, p. 37.

- ^ Vining, Miles (May 7, 2018). "ISOF Arms & Equipment Part 3 – Machine Guns". armamentresearch.com. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ Neville 2018, p. 38.

- ^ Erik Lawrence (2015). Practical Guide to the Operational Use of the DShK & DShKM Machine Gun. Erik Lawrence Publications. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-941998-22-9.

- ^ "FINNISH ARMY 1918–1945: ANTIAIRCRAFT MACHINEGUNS". Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ Harnden, Toby (2000).Bandit Country: The IRA and South Armagh. Coronet Books, pp. 360–361 ISBN 0-340-71737-8

- ^ Mills, Dan (2007). "16". Sniper One. Penguin Group. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-7181-4994-9.

They were Dshkes, a Russian-made beast of a thing that fires half-inch calibre rounds and was designed to bring down helicopters.

- ^ "الوكالة العربية السورية للأنباء". الوكالة العربية السورية للأنباء. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ Small Arms Survey (2008). "Light Weapons: Products, Producers, and Proliferation". Small Arms Survey 2008: Risk and Resilience. Cambridge University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-521-88040-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-08-30. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh Jones, Richard D.; Ness, Leland S., eds. (January 27, 2009). Jane's Infantry Weapons 2009/2010 (35th ed.). Coulsdon: Jane's Information Group. ISBN 978-0-7106-2869-5.

- ^ Thierry Vircoulon (2014-10-02). "Insights from the Burundian Crisis (I): An Army Divided and Losing its Way". International Crisis Group. Archived from the original on 2017-05-21. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ^ "Cameroon air strikes on Boko Haram". 29 December 2014. Archived from the original on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018 – via www.bbc.com.

- ^ Gander, Terry J.; Hogg, Ian V. Jane's Infantry Weapons 1995/1996. Jane's Information Group; 21 edition (May 1995). ISBN 978-0-7106-1241-0.

- ^ a b c d Miller, David (2001). The Illustrated Directory of 20th Century Guns. London: Salamander Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84065-245-1.

- ^ Army Recognition (2008-10-30). "Democratic Republic Congo Ranks combat uniforms Congolese army". armyrecognition.com. Archived from the original on 2017-06-02. Retrieved 2017-06-22.

- ^ eestimaa123 (2014-03-28). "Estonian Soldiers in Afghanistan". youtube.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "G3 Defence Magazine August 2010". calameo.com. Retrieved 15 December 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Neville 2018, p. 9.

- ^ NRT (2017-01-25). "Peshmerga Ministry: There will be no withdraw from liberated areas". NRT TV. Retrieved 2017-06-25.

- ^ de Tessières, Savannah (April 2012). Enquête nationale sur les armes légères et de petit calibre en Côte d'Ivoire: les défis du contrôle des armes et de la lutte contre la violence armée avant la crise post-électorale (PDF) (Report). Special Report No. 14 (in French). UNDP, Commission Nationale de Lutte contre la Prolifération et la Circulation Illicite des Armes Légères et de Petit Calibre and Small Arms Survey. p. 97. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-10-09. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

{{cite report}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ World Armies (2012-10-08). "Kenyan Army". flicker. Archived from the original on 2017-04-06. Retrieved 2017-04-05.

- ^ Small Arms Survey (2005). "Sourcing the Tools of War: Small Arms Supplies to Conflict Zones" (PDF). Small Arms Survey 2005: Weapons at War. Oxford University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-19-928085-8. Archived from the original on 2018-08-30. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- ^ Mongolian military museum. Ulaanbaatar. Sights of intersest Archived 2013-11-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ O'Halloran, Kevin. Rwanda: Unamir 1994/1995. Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 978-1-921941-48-1.

- ^ "12.7mm DShK heavy machinegun". Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ "Wyposażenie Wojsk Lądowych RP". Gdzie zaczyna się wojsko…. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ Gander, Terry J. (4 May 2001). "ROMARM machine guns". Jane's Infantry Weapons 2002-2003. p. 3407.

- ^ Small Arms Survey (2014). "Weapons tracing in Sudan and South Sudan" (PDF). Small Arms Survey 2014: Women and guns (PDF). Cambridge University Press. p. 224. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-10-14. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- ^ "Reported use by intelligence agency". Archived from the original on 2016-07-24.

Further reading

- Leszek Erenfeicht (29 August 2012). "Dushka: The Soviet Fifty Caliber". Small Arms Defense Journal. Vol. 4, No. 3.

- Koll, Christian (2009). Soviet Cannon: A Comprehensive Study of Soviet Arms and Ammunition in Calibres 12.7mm to 57mm. Austria: Koll. p. 53. ISBN 978-3-200-01445-9.

External links

- DShK and DShKM at guns.ru.

- Video of Operation