Osman I

| Osmān Gāzi عثمان غازى | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gazi Bey | |||||

Ottoman miniature (1563) depicting Osman I, located at Topkapı Palace | |||||

| Uç bey of the Sultanate of Rum | |||||

| Reign | c. 1280 ‒ c. 1299 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ertuğrul | ||||

| Successor | None | ||||

| 1st Ottoman Sultan (Bey) | |||||

| Reign | c. 1299 ‒ 1323/4 | ||||

| Predecessor | Office established | ||||

| Successor | Orhan | ||||

| Born | Unknown[1] Sultanate of Rum | ||||

| Died | 1323/4[2] Bursa, Ottoman Beylik | ||||

| Burial | Tomb of Osman Gazi, Osmangazi, Bursa Province | ||||

| Spouse | Malhun Hatun Rabia Bala Hatun | ||||

| Issue | See below | ||||

| |||||

| Ottoman Turkish | عثمان غازى | ||||

| Turkish | Osman Gazi | ||||

| Dynasty | Imperial House of Osman | ||||

| Father | Ertuğrul | ||||

| Mother | Unknown[4] | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

Osman I or Osman Ghazi (Template:Lang-ota; Template:Lang-tr; died 1323/4),[1][2] sometimes transliterated archaically as Othman, was the leader of the Ottoman Turks and the founder of the Ottoman dynasty. The dynasty bearing his name later established and ruled the Ottoman Empire (first known as the Ottoman Beylik or Emirate). This state, while only a small Turkmen[5] principality during Osman's lifetime, transformed into a world empire in the centuries after his death.[6] It existed until shortly after the end of World War I.

Due to the scarcity of historical sources dating from his lifetime, very little factual information about Osman has survived. Not a single written source survives from Osman's reign.[7] The Ottomans did not record the history of Osman's life until the fifteenth century, more than a hundred years after his death.[8] Because of this, historians find it very challenging to differentiate between fact and myth in the many stories told about him.[9] One historian has even gone so far as to declare it impossible, describing the period of Osman's life as a "black hole".[10]

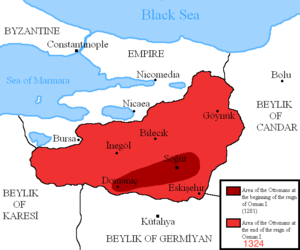

According to later Ottoman tradition, Osman's ancestors were descendants of the Kayı tribe of Oghuz Turks.[11] The Ottoman principality was just one of many Anatolian beyliks that emerged in the second half of the thirteenth century. Situated in the region of Bithynia in the north of Asia Minor, Osman's principality found itself particularly well-placed to launch attacks on the vulnerable Byzantine Empire, which his descendants would eventually go on to conquer.

Osman's name

Some scholars have argued that Osman's original name was Turkish, probably Atman or Ataman, and was only later changed to ʿOsmān, of Arabic origin. The earliest Byzantine sources, including Osman's contemporary George Pachymeres, spell his name as Ατουμάν (Atouman) or Ατμάν (Atman), whereas Greek sources regularly render both the Arabic form ʿUthmān and the Turkish version ʿOsmān with θ, τθ, or τσ. An early Arabic source mentioning him also writes ط rather than ث in one instance. Osman may thus have adopted the more prestigious Muslim name later in his life.[12] Arab scholars like Shihab al-Umari and Ibn Khaldun used the name Othman while Ibn Battuta, who visited the region during Orhan I's reign, called him Osmancık.[13] The suffix -cık (or -cuk), indicates the dimunitive in Turkish, thus he was known by the name of Osmancik, which means "Osman the Little", in order to differentiate between him and the third Caliph "Uthman the Great".[14]

Origin of the Ottoman Empire

The exact date of Osman's birth is unknown, and very little is known about his early life and origins due to the scarcity of sources and the many myths and legends which came to be told about him by the Ottomans in later centuries.[1][15] He was most likely born around the middle of the thirteenth century, possibly in 1254/5, the date given by the sixteenth-century Ottoman historian Kemalpaşazade.[16] According to Ottoman tradition, Osman's father Ertuğrul led the Turkic Kayı tribe west from Central Asia into Anatolia, fleeing the Mongol onslaught. He then pledged allegiance to the Sultan of the Anatolian Seljuks, who granted him dominion over the town of Söğüt on the Byzantine frontier.[17] This connection between Ertuğrul and the Seljuks, however, was largely invented by court chroniclers a century later, and the true origins of the Ottomans thus remain obscure.[18]

Osman became chief, or bey, upon his father’s death in c. 1280.[17] Nothing is known for certain about Osman's early activities, except that he controlled the region around the town of Söğüt and from there launched raids against the neighboring Byzantine Empire. The first datable event in Osman's life is the Battle of Bapheus in 1301 or 1302, in which he defeated a Byzantine force sent to counter him.[19]

Osman appears to have followed the strategy of increasing his territories at the expense of the Byzantines while avoiding conflict with his more powerful Turkish neighbors.[17] His first advances were through the passes which lead from the barren areas of northern Phrygia near modern Eskişehir into the more fertile plains of Bithynia; according to Stanford Shaw, these conquests were achieved against the local Byzantine nobles, "some of whom were defeated in battle, others being absorbed peacefully by purchase contracts, marriage contracts, and the like."[20]

Osman's Dream

Osman I had a close relationship with a local religious leader of dervishes named Sheikh Edebali, whose daughter he married. A story emerged among later Ottoman writers to explain the relationship between the two men, in which Osman had a dream while staying in the Sheikh's house.[21] The story appears in the late fifteenth-century chronicle of Aşıkpaşazade as follows:

He saw that a moon arose from the holy man's breast and came to sink in his own breast. A tree then sprouted from his navel and its shade compassed the world. Beneath this shade there were mountains, and streams flowed forth from the foot of each mountain. Some people drank from these running waters, others watered gardens, while yet others caused fountains to flow. When Osman awoke he told the story to the holy man, who said 'Osman, my son, congratulations, for God has given the imperial office to you and your descendants and my daughter Malhun shall be your wife.[22]

The dream became an important foundational myth for the empire, imbuing the House of Osman with God-given authority over the earth and providing its fifteenth-century audience with an explanation for Ottoman success.[23] The dream story may also have served as a form of compact: just as God promised to provide Osman and his descendants with sovereignty, it was also implicit that it was the duty of Osman to provide his subjects with prosperity.[24]

Military victories

Until the end of thirteenth century, Osman I's conquests include the areas of Bilecik (Belokomis), Yenişehir (Melangeia), İnegöl (Angelokomis) and Yarhisar (Köprühisar), and Byzantine castles in these areas.[25][26][27] According to Shaw, Osman's first real conquests followed the collapse of Seljuk authority when he was able to occupy the fortresses of Eskişehir and Kulucahisar. Then he captured the first significant city in his territories, Yenişehir, which became the Ottoman capital.[20]

In 1302, after soundly defeating a Byzantine force near Nicaea, Osman began settling his forces closer to Byzantine controlled areas.[28]

Alarmed by Osman's growing influence, the Byzantines gradually fled the Anatolian countryside. Byzantine leadership attempted to contain Ottoman expansion, but their efforts were poorly organized and ineffectual. Meanwhile, Osman spent the remainder of his reign expanding his control in two directions, north along the course of the Sakarya River and southwest towards the Sea of Marmara, achieving his objectives by 1308.[20] That same year his followers participated in conquest of the Byzantine city of Ephesus near the Aegean Sea, thus capturing the last Byzantine city on the coast, although the city became part of the domain of the Emir of Aydin.[28]

Osman's last campaign was against the city of Bursa.[29] Although Osman did not physically participate in the battle, the victory at Bursa proved to be extremely vital for the Ottomans as the city served as a staging ground against the Byzantines in Constantinople, and as a newly adorned capital for Osman's son, Orhan. Ottoman tradition holds that Osman died just after the capture of Bursa, but some scholars have argued that his death should be placed in 1324, the year of Orhan's accession.[30]

Family

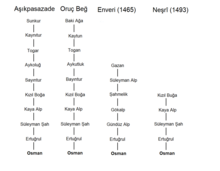

Due to the scarcity of sources about his life, very little is known about Osman's family relations. According to certain fifteenth-century Ottoman writers, Osman was descended from the Kayı branch of the Oghuz Turks, a claim which later became part of the official Ottoman genealogy and was eventually enshrined in the Turkish Nationalist historical tradition with the writings of M. F. Köprülü.[31] However, the claim to Kayı lineage does not appear in the earliest extant Ottoman genealogies. Thus many scholars of the early Ottomans regard it as a later fabrication meant to shore up dynastic legitimacy with regard to the empire's Turkish rivals in Anatolia.[11] Yazıcıoğlu Ali, in early 15th century, traced Osman's geneaology to Oghuz Khagan, the mythical ancestors of Western Turks, through his senior grandson of his senior son, so giving the Ottoman sultans primacy among Turkish monarchs.[32]

It is very difficult for historians to determine what is factual and what is legendary about the many stories the Ottomans told about Osman and his exploits, and the Ottoman sources do not always agree with each other.[33] According to one story, Osman had an uncle named Dündar with whom he had a quarrel early in his career. Osman wished to attack the local Christian lord of Bilecik, while Dündar opposed it, arguing that they already had enough enemies. Interpreting this as a challenge to his leadership position, Osman shot and killed his uncle with an arrow.[34] This story does not appear in many later Ottoman historical works. If it were true, it means that it was likely covered up in order to avoid tarnishing the reputation of the Ottoman dynasty's founder with the murder of a family member. It may also indicate an important change in the relationship of the Ottomans with their neighbors, shifting from relatively peaceful accommodation to a more aggressive policy of conquest.[35]

Marriages

- Malhun Hatun, daughter of Ömer Abdülaziz Bey[36]

- Rabia Bala Hatun, daughter of Sheikh Edebali[37]

Sons

- Alaeddin Pasha — died in 1332, born to Rabia[citation needed]

- Orhan I — born to Malhun[38]

- Çoban Bey[39] (buried in Söğüt);[40]

- Melik Bey[39] (buried in Söğüt);[40]

- Hamid Bey[39] (buried in Söğüt);[40]

- Pazarlu Bey[39] (buried in Söğüt);[40]

Daughter

- Fatma[39]

The Sword of Osman

The Sword of Osman (Template:Lang-tr) was an important sword of state used during the coronation ceremony of the Ottoman Sultans.[41] The practice started when Osman was girt with the sword of Islam by his father-in-law Sheik Edebali.[42] The girding of the sword of Osman was a vital ceremony which took place within two weeks of a sultan's accession to the throne. It was held at the tomb complex at Eyüp, on the Golden Horn waterway in the capital Constantinople. The fact that the emblem by which a sultan was enthroned consisted of a sword was highly symbolic: it showed that the office with which he was invested was first and foremost that of a warrior. The Sword of Osman was girded on to the new sultan by the Sharif of Konya, a Mevlevi dervish, who was summoned to Constantinople for that purpose.[43][better source needed]

Personality

Ottoman historiography depicts Osman as a semi-holy person.[44]

It is known that among the Turkoman tribes, the tribe or part of it was named after its leader. The fact that the Kayi tribe became known by the name of Osman, suggests that the tribe became powerful because of his excellent leadership.[45] Orientalist R. Rakhmanaliev writes that the historical role of Osman was that of a tribal leader, who enjoyed enormous success in uniting his people around him.[46]

The activities and personality of Osman as the founder of the state and dynasty are highly appreciated by historians of both the past and the present. The state and the dynasty of rulers are named after him. The population of the state was called Ottomans (Osmanlilar) until the beginning of the 20th century, that is until the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Historian F. Uspensky notes that Osman relied not only on force, but also cunningness.[47] Historian and writer Lord Kinross writes that Osman was a wise, patient ruler, whom people sincerely respected and were ready to serve him faithfully. He had a natural sense of superiority, but he never sought to assert himself with the help of power, and therefore he was respected not only by those who were equal in position, but also those who exceeded his abilities on the battlefield or on wisdom. Osman did not arouse feelings of rivalry in his people - only loyalty.[48] Herbert Gibbons believed that Osman was "great enough to exploit masterful people".[49]

According Kemal Kadafar, Osman for the Ottomans was the same as Romulus for the Romans.[50]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Kermeli, Eugenia (2009). "Osman I". In Ágoston, Gábor; Bruce Masters (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. p. 444.

Reliable information regarding Osman is scarce. His birth date is unknown and his symbolic significance as the father of the dynasty has encouraged the development of mythic tales regarding the ruler's life and origins, however, historians agree that before 1300, Osman was simply one among a number of Turkoman tribal leaders operating in the Sakarya region.

- ^ a b Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. p. 16.

By the time of Osman's death (1323 or 1324)...

- ^ Akgunduz, Ahmed; Ozturk, Said (2011). Ottoman History - Misperceptions and Truths. IUR Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-90-90-26108-9. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Heath W. Lowry (2003). The Nature of the Early Ottoman State. Albany: SUNY Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-7914-8726-6.

- ^ "Osman I". Encyclopedia Britannica. Osman I, also called Osman Gazi, (born c. 1258—died 1324 or 1326), ruler of a Turkmen principality in northwestern Anatolia who is regarded as the founder of the Ottoman Turkish state.

- ^ The Ottoman Empire, 1700-1999, Donald Quataert, page 4, 2005

- ^ Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. p. xii.

There is still not one authentic written document known from the time of ʿOsmān, and there are not many from the fourteenth century altogether.

- ^ Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. p. 93.

- ^ Finkel, Caroline (2005). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300-1923. Basic Books. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-465-02396-7.

Modern historians attempt to sift historical fact from the myths contained in the later stories in which the Ottoman chroniclers accounted for the origins of the dynasty[.]

- ^

Imber, Colin (1991). Elizabeth Zachariadou (ed.). The Ottoman Emirate (1300-1389). Rethymnon: Crete University Press. p. 75.

Almost all the traditional tales about Osman Gazi are fictitious. The best thing a modern historian can do is to admit frankly that the earliest history of the Ottomans is a black hole. Any attempt to fill this hole will result simply in more fables.

- ^ a b

Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. p. 122.

That they hailed from the Kayı branch of the Oğuz confederacy seems to be a creative "rediscovery" in the genealogical concoction of the fifteenth century. It is missing not only in Ahmedi but also, and more importantly, in the Yahşi Fakih-Aşıkpaşazade narrative, which gives its own version of an elaborate genealogical family tree going back to Noah. If there was a particularly significant claim to Kayı lineage, it is hard to imagine that Yahşi Fakih would not have heard of it.

- Lowry, Heath (2003). The Nature of the Early Ottoman State. SUNY Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-7914-5636-6.

Based on these charters, all of which were drawn up between 1324 and 1360 (almost one hundred fifty years prior to the emergence of the Ottoman dynastic myth identifying them as members of the Kayı branch of the Oguz federation of Turkish tribes), we may posit that...

- Lindner, Rudi Paul (1983). Nomads and Ottomans in Medieval Anatolia. Indiana University Press. p. 10.

In fact, no matter how one were to try, the sources simply do not allow the recovery of a family tree linking the antecedents of Osman to the Kayı of the Oğuz tribe.

- Lowry, Heath (2003). The Nature of the Early Ottoman State. SUNY Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-7914-5636-6.

- ^ Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. p. 124.

- ^ Ahmet Yaşar Ocak, (2000), Osmanli Devleti'nin kuruluşu: efsaneler ve gerçekler, p. 45 (in Turkish)

- ^ Kenje Kara, Daniel Prior, (2004), Archivum Ottomanicum, Volume 22, p. 140

- ^ Finkel, Caroline (2005). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300-1923. Basic Books. p. 12.

Beyond the likelihood that the first Ottoman sultan was a historical figure, a Turcoman Muslim marcher-lord of the Byzantine frontier in north-west Anatolia whose father may have been called Ertuğrul, there is little other biographical information about Osman.

- ^ Murphey, Rhoads (2008). Exploring Ottoman Sovereignty: Tradition, Image, and Practice in the Ottoman Imperial Household, 1400-1800. London: Continuum. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-84725-220-3.

- ^ a b c Stanford Shaw, History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey (Cambridge: University Press, 1976), vol. 1 ISBN 9780521291637, p. 13

- ^ Fleet, Kate (2010). "The rise of the Ottomans". In Fierro, Maribel (ed.). The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 2: The Western Islamic World, Eleventh to Eighteenth Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-521-83957-0.

The origins of the Ottomans are obscure. According to legend, largely invented later as part of the process of legitimising Ottoman rule and providing the Ottomans with a suitably august past, it was the Saljuq ruler ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn who bestowed rule on the Ottomans.

- ^ Imber, Colin (2009). The Ottoman Empire, 1300-1650: The Structure of Power (2 ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 8.

- Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. p. 129.

Of [military undertakings] we know nothing with certainty until the Battle of Bapheus, Osman's triumphant confrontation with a Byzantine force in 1301 (or 1302), which is the first datable incident in his life.

- Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. p. 129.

- ^ a b c Shaw, Ottoman Empire, p. 14

- ^ Kermeli, Eugenia (2009). "Osman I". In Ágoston, Gábor; Bruce Masters (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. p. 445.

Apart from these chronicles, there are later sources that begin to establish Osman as a mythic figure. From the 16th century onward a number of dynastic myths are used by Ottoman and Western authors, endowing the founder of the dynasty with more exalted origins. Among these is recounted the famous "dream of Osman" which is supposed to have taken place while he was a guest in the house of a sheikh, Edebali. [...] This highly symbolic narrative should be understood, however, as an example of eschatological mythology required by the subsequent success of the Ottoman emirate to surround the founder of the dynasty with supernatural vision, providential success, and an illustrious genealogy.

- Imber, Colin (1987). "The Ottoman Dynastic Myth". Turcica. 19: 7–27.

The attraction of Aşıkpasazade's story was not only that it furnished an episode proving that God had bestowed rulership on the Ottomans, but also that it provided, side by side with the physical descent from Oguz Khan, a spiritual descent. [...] Hence the physical union of Osman with a saint's daughter gave the dynasty a spiritual legitimacy and became, after the 1480s, an integral feature of dynastic mythology.

- Imber, Colin (1987). "The Ottoman Dynastic Myth". Turcica. 19: 7–27.

- ^ Finkel, Caroline (2005). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300-1923. Basic Books. p. 2., citing Lindner, Rudi P. (1983). Nomads and Ottomans in Medieval Anatolia. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 37. ISBN 0-933070-12-8.

- ^ Finkel, Caroline. Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300-1923. Basic Books. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-465-02396-7.

First communicated in this form in the later fifteenth century, a century and a half after Osman's death in about 1323, this dream became one of the most resilient founding myths of the empire.

- ^ Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. pp. 132–3.

- ^ Korobeĭnikov, Dimitri (2014). Byzantium and the Turks in the Thirteenth Century. Oxford University Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-01-98-70826-1. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Akgunduz, Ahmed; Ozturk, Said (2011). Ottoman History - Misperceptions and Truths. IUR Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-90-90-26108-9. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Lindner, Rudi Paul (2007). Explorations in Ottoman Prehistory. University of Michigan Press. p. 87. ISBN 9780472095070. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ a b Steven Runciman, The Fall of Constantinople 1453 (Cambridge: University Press, 1969) p. 32

- ^ Runciman, The Fall of Constantinople, p. 33

- ^ "Osman I". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. pp. 10, 37.

- ^ Colin Imber, (2002), The Ottoman Empire, 1300-1650, p. 95

- ^ Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. p. 105.

- Finkel, Caroline. Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300-1923. Basic Books. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-465-02396-7.

Modern historians attempt to sift historical fact from the myths contained in the later stories in which the Ottoman chroniclers accounted for the origins of the dynasty

- Finkel, Caroline. Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300-1923. Basic Books. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-465-02396-7.

- ^ Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. p. 105.

- ^ Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. pp. 107–8.

- ^ Leslie Pierce (1993). The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. London: Oxford University Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780195086775.

- ^ Duducu, Jem (2018-01-15). The Sultans: The Rise and Fall of the Ottoman Rulers and Their World: A 600-Year History. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 9781445668611.

- ^ Lowry, Heath (2003). The Nature of the Early Ottoman State. SUNY Press. p. 153.

- ^ a b c d e Lowry, Heath (2003). The Nature of the Early Ottoman State. SUNY Press. p. 73.

- ^ a b c d Ertuğrul Gazi ve Halime Sultan Türbesi

- ^ Frederick William Hasluck, [First published 1929], "XLVI. The Girding of the Sultan", in Margaret Hasluck, Christianity and Islam Under the Sultans II, pp. 604–622. ISBN 978-1-4067-5887-0

- ^ Frank R. C. Bagley, The Last Great Muslim Empires (Leiden: Brill, 1969), p. 2 ISBN 978-90-04-02104-4

- ^ "Girding on the Sword of Osman" (PDF). The New York Times. 1876-09-18. p. 2. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- ^ Ihsanoglu, E. "History of the Ottoman state, society and civilization: in 2 volumes"; translated from Turkish by Feonova, ed. by M.S. Meyer; Eastern Literature, 2006. V.1. p. 6; ISBN 5-02-018511-6.

- ^ Ihsanoglu, E. "History of the Ottoman state, society and civilization: in 2 volumes"; Translation from Turkish by V.B.Feonova, ed. by M.S.Meyer; Eastern Literature, 2006. V. 1; p. 6; ISBN 5-02-018511-6.

- ^ R.Rakhmanaliev. "Empire of the Turks. Great civilization. Turkic peoples in World History since the 10th century B.C. to the 20th century". Ripol Classic, 2008. ISBN 5386008471, 9785386008475.

- ^ Uspensky, F. "History of the Byzantine Empire: XI-XV centuries. Eastern question". Moscow, Mysl', 1996. ISBN 524400882X, 9785244008821.

- ^ Kinross, Lord. "The Ottoman Centuries. The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire". Harper Collins, 1979.

- ^ Gibbons, Herbert Adams. "The Foundation of the Ottoman Empire: A History of the Osmanlis Up To the Death of Bayezid I 1300-1403". — Routledge, 2013. p. 27. ISBN 1135029822, 9781135029821.

- ^ Kafadar, Kemal. "Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State". University of California Press, 1995. p. 1. ISBN 0520206002, 9780520206007

Bibliography

- Finkel, Caroline (2005). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300-1923. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02396-7.

- Fleet, Kate (2010). "The rise of the Ottomans". In Maribel Fierro (ed.). The New Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 313–331. ISBN 978-0-521-83957-0.

- Imber, Colin (1987). "The Ottoman Dynastic Myth". Turcica. 19: 7–27.

- Imber, Colin (2009). The Ottoman Empire, 1300-1650: The Structure of Power (2 ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-57451-9.

- Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20600-7.

- Kermeli, Eugenia (2009). "Osman I". In Ágoston, Gábor; Bruce Masters (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. New York: Facts on File. pp. 444–6. ISBN 978-0-8160-6259-1.

- Lindner, Rudi P. (1983). Nomads and Ottomans in Medieval Anatolia. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-933070-12-8.

- Lowry, Heath (2003). The Nature of the Early Ottoman State. Albany: SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-5636-6.

- Murphey, Rhoads (2008). Exploring Ottoman Sovereignty: Tradition, Image, and Practice in the Ottoman Imperial Household, 1400-1800. London: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-84725-220-3.

- Zachariadou, Elizabeth, ed. (1991). The Ottoman Emirate (1300-1389). Rethymnon: Crete University Press.

External links

![]() Media related to Osman I at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Osman I at Wikimedia Commons