Joseph James DeAngelo

It has been suggested that Visalia Ransacker be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since July 2020. |

Joseph James DeAngelo | |

|---|---|

2018 mugshot of DeAngelo | |

| Born | Joseph James DeAngelo Jr. November 8, 1945 |

| Other names | |

| Occupation(s) | Police officer, mechanic |

| Height | ≈5 ft 10 in (1.78 m) |

| Spouse |

Sharon Marie Huddle

(m. 1973; div. 2019) |

| Children | 3 daughters |

| Conviction(s) | Murder and kidnapping |

| Details | |

| Victims |

|

Span of crimes | 1973–1986 |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | California |

Date apprehended | April 24, 2018 |

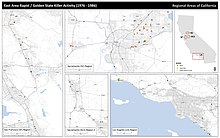

Joseph James DeAngelo Jr. (born November 8, 1945) is an American serial killer, serial rapist, burglar and former police officer who committed at least 13 murders, more than 50 rapes, and over 100 burglaries in California between 1973 and 1986.[4][5][6] He was responsible for at least three crime sprees throughout California, each of which spawned a different nickname in the press, before it became evident that they were committed by the same offender. He began as a burglar (the Visalia Ransacker) before moving to the Sacramento area, where he was known as the East Area Rapist and was linked by modus operandi to additional attacks in Contra Costa County, Stockton, and Modesto.[7][8] DeAngelo committed serial murders in southern California, where he was known as the Night Stalker and later the Original Night Stalker (because serial killer Richard Ramirez had also been called the "Night Stalker"). He is believed to have taunted and threatened both victims and police in obscene phone calls, and possibly written communications.

During the decades-long investigation, several suspects were cleared through DNA evidence, alibi, or other investigative methods.[2][9] In 2001, after DNA testing indicated that the East Area Rapist and the Original Night Stalker were the same person, the acronym EARONS (eer-onz) started to be used.[5] The case was a factor in the establishment of California's DNA database, which collects DNA from all accused and convicted felons in California[10] and has been called second only to Virginia's in effectiveness in solving cold cases.[11] To heighten awareness of the case, crime writer Michelle McNamara coined the name Golden State Killer in early 2013.[5]

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and local law-enforcement agencies held a news conference on June 15, 2016, to announce a renewed nationwide effort, offering a $50,000 reward for his capture.[12] On April 24, 2018, authorities charged 72-year-old DeAngelo with eight counts of first-degree murder, based upon DNA evidence;[13][14] investigators had identified members of DeAngelo's family through forensic genetic genealogy.[15] This was also the first announcement connecting the Visalia Ransacker crimes to DeAngelo.[16] Owing to California's statute of limitations on pre-2017 rape cases,[17] DeAngelo could not be charged with 1970s rapes,[18] but he was charged in August 2018 with 13 related kidnapping and abduction attempts.[19] On June 29, 2020, DeAngelo pleaded guilty to multiple counts of murder and kidnapping.[20] As part of the plea bargain, DeAngelo also admitted to numerous crimes he had not been formally charged with, including rapes.[21]

Early life and career

DeAngelo was born on November 8, 1945, in Bath, New York to Joseph James DeAngelo Sr., a U.S. Army Sergeant, and Kathleen Louise DeGroat.[22] He has two younger sisters, and a younger brother. A relative reported that when DeAngelo was 9 or 10 years old he witnessed his 7-year-old sister being raped by two airmen in a warehouse in West Germany, where the family was stationed at the time.[23]

Between 1959 and 1960, he attended Mills Junior High School in Rancho Cordova, California. Beginning in 1961, he attended Folsom High School, from which he received a GED certificate in 1964. He played on the school's junior varsity baseball team.[24][25]

DeAngelo joined the U.S. Navy in September 1964,[26] and served for 22 months during the Vietnam War as a damage controlman on the cruiser USS Canberra[27] and USS Piedmont.[28] Beginning August 1968, DeAngelo attended Sierra College in Rocklin, California; he graduated with an associate degree in police science, with honors.[29]

In May 1970, DeAngelo became engaged to Bonnie Jean Colwell, a classmate at Sierra College, but she reportedly broke off the relationship. Investigators believe this might be connected to the offender saying, "I hate you, Bonnie!", during one of the attacks.[30][31]

In 1971, he attended Sacramento State University, where he earned a bachelor's degree in criminal justice.[25][26] He later took post-graduate courses[26] and further police training at the College of the Sequoias in Visalia, then completed a 32-week police internship at the Roseville Police Department.[32]

From May 1973 to August 1976, he was a burglary unit police officer in Exeter (a town of about 5,000 people, near Visalia),[33] having relocated from Citrus Heights.[24] He then served in Auburn from August 1976 to July 1979, when he was arrested for shoplifting a hammer and dog repellent; he was sentenced to six months probation and fired that October.[30][34]

In November 1973, he married Sharon Marie Huddle in Placer (now known as Loomis). In 1980, they purchased the house in Citrus Heights where he was eventually arrested.[28] Huddle became an attorney in 1982, and they had three daughters, two of whom were born in Sacramento and one in Los Angeles, before the couple separated in 1991.[citation needed] In July 2018, Huddle filed for a divorce.[24][31][35] They were divorced in 2019.[36]

His employment history in the 1980s is unknown.[30] From 1990 until his retirement in 2017, he worked as a truck mechanic at a Save Mart Supermarkets distribution center in Roseville.[24][37] He was arrested in 1996 over an incident at a gas station; the charge was dismissed.[38]

His brother-in-law said that DeAngelo casually brought up the East Area Rapist in conversation around the time of the original crimes. Neighbors reported that DeAngelo frequently engaged in loud, profane outbursts.[34] One neighbor reported that his family received a phone message from DeAngelo threatening to "deliver a load of death" because of their barking dog.[39] He was living with a daughter and granddaughter at the time of his arrest.[30]

Crimes

DNA evidence linked DeAngelo to eight murders in Goleta, Ventura, Dana Point, and Irvine; two other murders in Goleta, lacking DNA evidence, were linked by modus operandi.[40][41] He pleaded guilty to three other murders: two in Rancho Cordova, and one in Visalia.[2] DeAngelo also committed more than 50 known rapes in the California counties of Sacramento, Contra Costa, Stanislaus, San Joaquin, Alameda, Santa Clara, and Yolo, and was linked to hundreds of incidents of burglaries, thefts, vandalism, peeping, stalking, and prowling.[42]

Visalia Ransacker (May 1973 – December 1975)

It was long suspected that the training ground of the criminal who became the East Area Rapist was Visalia, California[43][44][45][46] (although earlier Visalia crimes dating back as early as May 1973 and other sprees like the 'Cordova Cat Burglar'[47] or the 'Exeter Ransacker',[48] as well as burglaries that took place after the McGowen shooting, are now suspected to be linked as well).[33][49] Over a period of 20 months, the Ransacker is believed to have been responsible for one murder and around 120 burglaries.[50] Most of the Ransacker's activities involved breaking into houses, going through (or vandalizing) the owners' possessions, scattering women's underclothing, stealing coins and low-value or personal items, while often ignoring banknotes and other valuable items in plain sight.[51]

In late April 2018, the Visalia chief of police stated that while there is no DNA linking DeAngelo to the Central Valley cases, his department has other evidence that will play a role in the investigation, and that he was "confident that the Visalia Ransacker has been captured."[52] Though the statutes of limitations for the burglaries have each expired,[7][53] DeAngelo was formally charged on August 13, 2018, with the first degree murder of Claude Snelling in 1975.[53][54] In 2020, DeAngelo pleaded guilty to the murder of Claude Snelling, confirming that he was the Visalia Ransacker.[55]

East Area Rapist (June 1976 – July 1979)

DeAngelo moved to the Sacramento area in 1976, where his crimes escalated from burglary to rape. The crimes initially centered on the then-unincorporated areas of Carmichael, Citrus Heights and Rancho Cordova, east of Sacramento.[6] His initial modus operandi was to stalk middle-class neighborhoods at night in search of women who were alone in one-story homes, usually near a school, creek, trail or other open space that would provide a quick escape.[56] He was seen a number of times, but always successfully fled; on one occasion, he shot and seriously wounded a young pursuer.[2]: 187–188

Most victims had seen (or heard) a prowler on their property before the attacks, and many had experienced break-ins. Police believed that the offender would conduct extensive reconnaissance in a targeted neighborhood — looking into windows and prowling in yards — before selecting a home to attack. It was believed that he sometimes entered the homes of future victims to unlock windows, unload guns, and plant ligatures for later use. He frequently telephoned future victims, sometimes for months in advance, to learn their daily routines.[5][58]

Although he originally targeted women alone in their homes or with children,[9][59] DeAngelo eventually preferred attacking couples.[9][60] His usual method was to break in through a window or sliding glass door and awaken the sleeping occupants with a flashlight, threatening them with a handgun.[9] Victims were then bound with ligatures (often shoelaces) which he found or brought with him, blindfolded and gagged with towels which he had ripped into strips. The female victim was usually forced to tie up her male companion before she was bound.[61] The bindings were often so tight that the victims' hands were numb for hours after being untied.[2]: 434 He separated the couple, often stacking dishes on the male's back and threatening to kill everyone in the house if he heard them rattle. He moved the woman to the living room and often raped her repeatedly, sometimes for several hours.[9][61][62]

DeAngelo sometimes spent hours in the home ransacking closets and drawers,[63] eating food in the kitchen, drinking beer, raping the woman again or making additional threats. Victims sometimes thought he had left the house before he "jump[ed] from the darkness."[61] He typically stole items, often personal objects and items of little value but occasionally cash and firearms. He then crept away, leaving victims uncertain if he had left. He was believed to escape on foot through a series of yards and then use a bicycle to go home or to a car, making extensive use of parks, schoolyards, creek beds and other open spaces which kept him off the street.[2]

The rapist operated in Sacramento County from the first attacks in June 1976 until May 1977. After a three-month gap, he struck in nearby San Joaquin County in September before returning to Sacramento for all but one of the next ten attacks. The rapist attacked five times during the summer of 1978 in Stanislaus and Yolo counties before disappearing again for three months. Attacks then moved primarily to Contra Costa County in October and lasted until July 1979.

Rapes

| # | Date | Time | Location | County | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Friday, June 18, 1976 | 4:00 a.m. | Rancho Cordova | Sacramento | [64][65][66] |

| 2 | Saturday, July 17, 1976 | 2:00 a.m. | Carmichael | Sacramento | Marlborough Way, Del Dayo Neighborhood[65][66] |

| 3 | Sunday, August 29, 1976 | 3:20 a.m. | Rancho Cordova | Sacramento | [65][66] |

| 4 | Saturday, September 4, 1976 | 11:30 p.m. | Carmichael | Sacramento | [65][66] |

| 5 | Tuesday, October 5, 1976 | 6:45 a.m. | Citrus Heights | Sacramento | [65][66][67] |

| 6 | Saturday, October 9, 1976 | 4:30 a.m. | Rancho Cordova | Sacramento | [65][66] |

| 7 | Monday, October 18, 1976 | 2:30 a.m. | Carmichael | Sacramento | Kipling Drive, Del Dayo Neighborhood[65][66] |

| 8 | Monday, October 18, 1976 | 11:00 p.m. | Rancho Cordova | Sacramento | [65][66] |

| 9 | Wednesday, November 10, 1976 | 7:30 p.m. | Citrus Heights | Sacramento | Greenback Lane |

| 10 | Saturday, December 18, 1976 | 7:00 p.m. | Carmichael | Sacramento | |

| 11 | Tuesday, January 18, 1977 | 11:00 p.m. | Sacramento | Sacramento | Glenbrook/College Greens area[68] |

| 12 | Monday, January 24, 1977 | 12:00 a.m. | Citrus Heights | Sacramento | Primrose Drive [69] |

| 13 | Monday, February 7, 1977 | 6:45 a.m. | Carmichael | Sacramento | Crestview Drive and Madison Ave.[70] |

| 14 | Wednesday, February 16, 1977 | 10:30 p.m. | Sacramento | Sacramento | Ripon Court[71] |

| 15 | Tuesday, March 8, 1977 | 4:00 a.m. | Arden-Arcade | Sacramento | Robertson and Whitney Ave.[72] |

| 16 | Friday, March 18, 1977 | 10:45 p.m. | Rancho Cordova | Sacramento | [73] |

| 17 | Saturday, April 2, 1977 | 3:20 a.m. | Orangevale | Sacramento | Madison and Main Ave. |

| 18 | Friday, April 15, 1977 | 2:30 a.m. | Carmichael | Sacramento | Madison and Manzanita Avenues[74] |

| 19 | Tuesday, May 3, 1977 | 3:00 a.m. | Sacramento | Sacramento | Glenbrook/College Greens area[75] |

| 20 | Thursday, May 5, 1977 | 2:40 a.m. | Orangevale | Sacramento | [75] |

| 21 | Saturday, May 14, 1977 | 3:45 a.m. | Citrus Heights | Sacramento | Greenback Lane and Birdcage Street[76] |

| 22 | Tuesday, May 17, 1977 | 1:30 a.m. | Carmichael | Sacramento | Sand Bar Circle, Del Dayo Neighborhood[77] |

| 23 | Saturday, May 28, 1977 | 1:00 a.m. | Parkway | Sacramento | Sky Parkway neighborhood[78] |

| 24 | Tuesday, September 6, 1977 | 1:30 a.m. | Stockton | San Joaquin | Lincoln Village West neighborhood[79] |

| 25 | Saturday, October 1, 1977 | 1:30 a.m. | La Riviera | Sacramento | La Riviera and Tuolumne Dr.[80] |

| 26 | Friday, October 21, 1977 | 3:00 a.m. | Foothill Farms | Sacramento | Elkhorn Blvd./Diablo Dr.[81] |

| 27 | Saturday, October 29, 1977 | 1:45 a.m. | Arden-Arcade | Sacramento | Woodson Ave.[82] |

| 28 | Thursday, November 10, 1977 | 3:00 a.m. | Sacramento | Sacramento | La Riviera Dr. near Watt Ave.[83] |

| 29 | Friday, December 2, 1977 | 11:30 p.m. | Foothill Farms | Sacramento | Brett and Revelstoke Dr.[84] |

| 30 | Saturday, January 28, 1978 | 10:15 p.m. | Carmichael | Sacramento | Winding Way, east of Walnut Ave.[85] |

| 31 | Saturday, March 18, 1978 | 11:00 p.m. | Stockton | San Joaquin | Parkwoods neighborhood[86] |

| 32 | Friday, April 14, 1978 | 10:00 p.m. | Sacramento | Sacramento | Seamas and Riverside Aves., Little Pocket[87][88] |

| 33 | Monday, June 5, 1978 | 2:30 a.m. | Modesto | Stanislaus | Northeastern Modesto[88][89] |

| 34 | Wednesday, June 7, 1978 | 3:55 a.m. | Davis | Yolo | North of UC Davis[90] |

| 35 | Friday, June 23, 1978 | 1:30 a.m. | Modesto | Stanislaus | Northeastern Modesto |

| 36 | Saturday, June 24, 1978 | 3:15 a.m. | Davis | Yolo | Rivendell area |

| 37 | Thursday, July 6, 1978 | 2:50 a.m. | Davis | Yolo | Westwood Division[91] |

| 38 | Saturday, October 7, 1978 | 2:30 a.m. | Concord | Contra Costa | [92] |

| 39 | Friday, October 13, 1978 | 4:30 a.m. | Concord | Contra Costa | [93] |

| 40 | Saturday, October 28, 1978 | 4:30 a.m. | San Ramon | Contra Costa | [94] |

| 41 | Saturday, November 4, 1978 | 3:30 a.m. | San Jose | Santa Clara | |

| 42 | Saturday, December 2, 1978 | 4:30 a.m. | San Jose | Santa Clara | |

| 43 | Saturday, December 9, 1978 | 2:00 a.m. | Danville | Contra Costa | |

| 44 | Monday, December 18, 1978 | 6:30 p.m. | San Ramon | Contra Costa | [95][96] |

| 45 | Tuesday, March 20, 1979 | 5:00 a.m. | Rancho Cordova | Sacramento | [95][96] |

| 46 | Wednesday, April 4, 1979 | 1:00 a.m. | Fremont | Alameda | [97] |

| 47 | Saturday, June 2, 1979 | 11:30 p.m. | Walnut Creek | Contra Costa | [98] |

| 48 | Monday, June 11, 1979 | 4:00 a.m. | Danville | Contra Costa | [99] |

| 49 | Monday, June 25, 1979 | 4:00 a.m. | Walnut Creek | Contra Costa | [100] |

| 50 | Thursday, July 5, 1979 | 3:45 a.m. | Danville | Contra Costa | [101] |

Murders

A young Sacramento couple, Brian Maggiore, a military policeman at Mather Air Force Base, and Katie Maggiore, were walking their dog in the Rancho Cordova area on the night of February 2, 1978, near where five East Area Rapist attacks had occurred.[102] The Maggiores fled after a confrontation in the street, but were chased down and shot dead.[103] Some investigators suspected that they had been murdered by the East Area Rapist because of their proximity to the other attacks' location, and a shoelace was found nearby.[2] The FBI announced on June 15, 2016, that it was confident that the East Area Rapist murdered the Maggiores.[104] On June 29, 2020 DeAngelo entered a plea of guilty to these murders. [105]

Original Night Stalker (October 1979 – May 1986)

Shortly after the rape committed on July 5, 1979, DeAngelo moved to southern California and began killing his victims, first striking in Santa Barbara County in October. The attacks lasted until 1981 (with a lone 1986 attack). Only the couple in the first attack survived, alerting neighbors and forcing the intruder to flee; the other victims were murdered by gunshot or bludgeoning. Since DeAngelo was not linked to these crimes for decades, he was known as the Night Stalker in the area before being renamed the Original Night Stalker after serial killer Richard Ramirez received the former nickname.[106]

| # | Date | Victim(s) | Location | County |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Monday, October 1, 1979 | None (attempted murder; botched attack) | Queen Ann Lane, Goleta[107] | Santa Barbara |

| 2 | Sunday, December 30, 1979 | Robert Offerman, Debra Manning | Goleta[108] | Santa Barbara |

| 3 | Thursday, March 13, 1980 | Charlene & Lyman Smith | Ventura[109] | Ventura |

| 4 | Tuesday, August 19, 1980 | Keith & Patrice Harrington | Dana Point[110] | Orange |

| 5 | Friday, February 6, 1981 | Manuela Witthuhn | Irvine[110][111] | Orange |

| 6 | Monday, July 27, 1981 | Cheri Domingo, Gregory Sanchez | Goleta[112] | Santa Barbara |

| 7 | Sunday, May 4, 1986 | Janelle Cruz | Irvine[41][113] | Orange |

1979

On October 1, an intruder broke in and tied up a Goleta couple.[2]: 434 Alarmed by hearing him say "I'll kill 'em" to himself,[2]: 435 [9] the man and woman tried to escape when he left the room and the woman screamed. Realizing that the alarm had been raised, the intruder fled on a bicycle.[9] A neighbor (an FBI agent) responded to the noise and pursued the perpetrator, who abandoned the bicycle and a knife and fled on foot through local backyards.[2]: 435 The attack was later linked to the Offerman–Manning murders by shoe prints and twine used to bind the victims.[2]: 438

On December 30, 44-year-old Robert Offerman and 35-year-old Debra Alexandra Manning were found shot dead at Offerman's condominium on Avenida Pequena in Goleta.[114] Offerman's bindings were untied, indicating that he had lunged at the attacker. Neighbors had heard gunshots.[114] Paw prints of a large dog were found at the scene, leading to speculation that the killer may have brought one with him.[2]: 446 The killer also broke into the vacant adjoining residence and stole a bicycle, later found abandoned on a street north of the scene, from a third residence in the complex.[3]

1980

On March 13, 33-year-old Charlene Smith and 43-year-old Lyman Smith were found murdered in their Ventura home;[115] Charlene Smith had been raped.[9] A log from a woodpile on the side of the house was used to bludgeon the victims to death.[2]: 440 [116] Their wrists and ankles had been bound with drapery cord.[2]: 441 [9] An unusual Chinese knot, a diamond knot, was used on Charlene's wrists;[2]: 441 the same knot was noted in the Sacramento East Area Rapist attacks, at least one confirmed case of which was publicly known.[3] The murderer was, therefore, briefly given the name Diamond Knot Killer.[117]

On August 19, 24-year-old Keith Eli Harrington and 27-year-old Patrice Briscoe Harrington were found bludgeoned to death in their home on Cockleshell Drive in Dana Point's Niguel Shores gated community.[118] Patrice Harrington had also been raped.[9][119] Although there was evidence that the Harringtons' wrists and ankles were bound, no ligatures or murder weapon were found at the scene.[118] The Harringtons had been married for three months at the time of their deaths.[118] Patrice was a nurse in Irvine, and Keith was a medical student at UC Irvine.[2][118] Keith's brother Bruce later spent nearly $2 million supporting California Proposition 69 authorizing DNA collection from all California felons and certain other criminals.[9][108]

1981

On February 6, 28-year-old Manuela Witthuhn was raped and murdered in her Irvine home.[9][120] Although Witthuhn's body had signs of being tied before she was bludgeoned,[9] no ligatures or murder weapon were found. The victim was married; her husband was away hospitalized and she was alone at the time of the attack.[120] Witthuhn's television was found in the backyard, possibly the killer's attempt to make the crime appear to be a botched robbery.[2]

On July 27, 35-year-old Cheri Domingo and 27-year-old Gregory Sanchez became the Original Night Stalker's 10th and 11th murder victims.[121] Both were attacked in Domingo's residence on Toltec Way in Goleta[2]: 444 (several blocks south of Robert Offerman's condominium), where she was living temporarily; it was owned by a relative and up for sale.[122] The offender entered the house through a small bathroom window. Sanchez had not been tied,[2]: 445 and was shot and wounded in the cheek before he was bludgeoned to death with a garden tool.

Some believe that Sanchez may have realized he was dealing with the man responsible for the Offerman–Manning murders, and tried to tackle the killer rather than be tied up. Again, no neighbors responded to the gunshot.[2]: 445 [122] Sanchez's head was covered with clothes pulled from the closet.[2]: 444 Domingo was raped and bludgeoned; bruises on her wrists and ankles indicated that she had been tied,[2]: 445 although the restraints were missing.[123] A piece of shipping twine was found near the bed, and fibers from an unknown source were scattered over her body.[124] Authorities believed that the attacker may have worked as a painter or in a similar job at the Calle Real Shopping Centre.[123][125][126]

1986

On May 4, 18-year-old Janelle Lisa Cruz was found after she was raped[41][113] and bludgeoned to death in her Irvine home.[127] Her family was on vacation in Mexico at the time of the attack.[9][120] A pipe wrench, reported missing by Cruz's stepfather, was thought to be the murder weapon.[2]: 458

The southern California murders were not initially thought to be connected by investigators in their respective jurisdictions. A Sacramento detective strongly believed that the East Area Rapist was responsible for the Goleta attacks, but the Santa Barbara County Sheriff's Department attributed them to a local career criminal who was later murdered. Investigating the crimes not committed in Goleta caused local police to follow false leads related to men who were close to the female victims. One person, later cleared, was charged with two murders. The cases were linked almost entirely by DNA testing, many years later.[2]

Suspect profile

Known physical characteristics

These physical characteristics are considered factual based on crime-scene evidence and nearly-universal agreement by victims and law enforcement:

- White male

- About 5 ft 10 in (1.78 m) tall

- Slender, athletic build

- Size 9 to 9+1⁄2 shoe

- Type A blood

- Non-secretor: His sperm does not contain blood-group antigens.[128]

- Physically agile and capable of sprinting, bicycling, and scaling fences

Probable characteristics

These physical characteristics are considered probable; a small percentage of victims described the perpetrator differently:

- 18–25 years old when the rapes began in 1976; authorities believed him to be between 60 and 75 years old in 2018.[129]

According to the Sacramento County Sheriff's Department, microscopic paint chips were found at three crime scenes (two homicides and a rape).[130] This suggests that the Golden State Killer may have worked in construction, possibly using a paint spray gun.[131] Construction work had been ongoing near the 1979 Goleta murder scene, and a cold-case investigator contacted the developer in 2013 to identify subcontractors working at the site and obtain employment records.[130]

Psychological profile

After criminologists matched serological evidence found at the southern California murder scenes, a speculative psychological profile of the Golden State Killer was compiled based on a probabilistic analysis. According to Leslie D'Ambrosia, primary author of the profile, the Golden State Killer probably had the following characteristics:[128]

- An emotional age equivalent to a 26- to 30-year-old at the time the murders began in 1979

- Engaged in paraphilic behavior and brutal sex in his personal life

- Engaged in sex with prostitutes

- Had some knowledge of police investigative methods and evidence-gathering techniques

- Sexually functional, capable of ejaculation with consenting and non-consenting partners

- Dressed well and would not stand out in upscale neighborhoods

- Lived or worked near Ventura, California, in 1980

- Good physical condition

- Skilled, experienced cat burglar, and may have begun as such

- Had a criminal record as a teenager which was expunged

- Had some means of income, but did not work in the early-morning hours

- Hated women for actual (or perceived) wrongs

- Intelligent and articulate

- Neat and well-organized in his personal life, and drove a well-maintained car

- Peeped in the windows of many people who were not attacked

- Self-assured and confident

The profile speculated that the killer might have been incarcerated after Janelle Cruz's murder or killed in the commission of a similar crime; it suggested a review of late-1980s hot prowl burglaries in which a lone male offender had been killed. It indicated a slight chance that the Golden State Killer committed suicide, and that he was unlikely to be confined in a mental institution.[128]

According to the profile, teleprinter bulletins were broadcast to law-enforcement agencies throughout the United States after the original homicides. The bulletins requested information on similar home invasions involving sexual assault, murder, bludgeoning, multiple victims, and bondage. As of 2015[update], no similar crimes had been reported. The profile posited that the Golden State Killer could have continued committing his crimes in another country whose records were not linked.[128]

Communications

Written

"Excitement's Crave" poem

In December 1977, someone claiming to be the East Area Rapist sent a poem, "Excitement's Crave", to The Sacramento Bee, the Sacramento mayor's office, and television station KVIE.[2] On December 11, a masked man eluded pursuit by law-enforcement personnel after alerting authorities by telephone that he would strike on Watt Avenue that night.[132]

Excitement's Crave

All those mortal's surviving birth / Upon facing maturity,

Take inventory of their worth / To prevailing society.

Choosing values becomes a task; / Oneself must seek satisfaction.

The selected route will unmask / Character when plans take action.

Accepting some work to perform / At fixed pay, but promise for more,

Is a recognized social norm, / As is decorum, seeking lore.

Achieving while others lifting / Should be cause for deserving fame.

Leisure tempts excitement seeking, / What's right and expected seems tame.

"Jessie James" has been seen by all, / And "Son of Sam" has an author.

Others now feel temptations call. / Sacramento should make an offer.

To make a movie of my life / That will pay for my planned exile.

Just now I' d like to add the wife / Of a Mafia lord to my file.

Your East Area Rapist

And deserving pest.

See you in the press or on T.V.[2]: p. 304

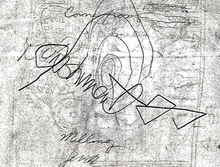

Homework pages and punishment map (December 9, 1978)

During the investigation of the 42nd attack in Danville, investigators discovered three sheets of notebook paper near where a suspicious vehicle had reportedly been parked.[5] The first sheet contains what appears to be an essay on General George Armstrong Custer.[5]

The second sheet contains a journal-style entry describing a teacher who made students write lines, which the author found humiliating:[5]

"Mad is the word, the word that reminds me of 6th grade. I hated that year ... I wish I had know what was going to be going on during my 6th grade year, the last and worst year of elementary school. Mad is the word that remains in my head about my dreadful year as a 6th grader. My Madness was one that was caused by disapointments that hurt me very much. Dissapointments from my teacher, such as feild trips that were planed, then canncled. My 6th grade teacher gave me a lot of dissapointments which made me very mad and made me built a state of haterd in my heart, no one ever let me down that hard before and I never hated anyone as much as I did him. Disapointment wasn't the only reason that made me mad in my sixth grade class, another was getting in trouble at school espeically talking thats what really bugged me was writing sentances, those awful sentance that my teacher made ... me write, hours and hours Id sit and write 50-100-150 sentance day and night I write those dreadful Paragraphs which embarrased me and more inportant it made me ashamed of myself which in turn, deep down in side made me realize that writing sentance wasn't fair it wasn't fair to make me suffer like that, it just wasn't fair to make me sit and wright until my bones aked, until my hand felt every horrid pain it ever had and as I wrote, I got mader and mader until I cried, I cried because I was ashamed I cried because I was discusted, I cried because I was mad, and I cried for myself, kid who kept on having to write those dane sentances. My Angryness from Sixth grade will scar my memory for life and I will be ashamed for my sixth grade year forever"

On the last sheet was a hand-drawn map of what appears to be a suburban neighborhood, with the word "punishment" scrawled across the reverse side.[126] Investigators were unable to identify the area depicted in the map, although the artist clearly had knowledge of architectural layout and landscape design.[133] According to Detective Larry Pool, the map is a fantasy location representing the rapist's desired striking ground.[5]

Phone calls

"I'm the East Side Rapist" (March 18, 1977)

On March 18, 1977, the Sacramento County Sheriff's Office received three calls from a man claiming to be the East Area Rapist; none was recorded.[134] The first two calls, received at 4:15 and 4:30 p.m., were identical and ended with the caller laughing and hanging up. The final call came in at 5:00 p.m., with the caller saying: "I'm the East Side Rapist and I have my next victim already stalked and you guys can't catch me."

"You're never gonna catch me" (December 2, 1977)

A man claiming to be the rapist called the Sacramento Police, saying: "You're never gonna catch me, East Area Rapist, you dumb fuckers, I'm gonna fuck again tonight. Careful!" The call was recorded and later released.[58] Similarly to the previous call, the next victim was attacked the same night.

"Merry Christmas" (December 9, 1977)

A previous victim received a phone call during the 1977 Christmas season which she attributed to her attacker. The caller said, "Merry Christmas, it's me again!"[2]: 301

"Watt Avenue" (December 10, 1977)

Shortly before 10:00 p.m. on December 10, 1977, Sacramento authorities received two identical calls, saying: "I am going to hit tonight. Watt Avenue." Both were recorded, and the caller was identified as the same person who placed the December 2 call. Law-enforcement patrols were increased that night,[2] and at 2:30 a.m. a masked man eluded officers after being seen bicycling on the Watt Avenue bridge. When spotted again at 4:30 a.m., he discarded the bicycle[132] and fled on foot. The bicycle had been stolen.

"Gonna kill you" (January 2, 1978)

The first known rape victim received a wrong-number call asking for "Ray" on January 2, 1978. The call was recorded, and police suspect that it may be the same caller who made a threatening call to her later that evening.[135] That call was also recorded and identified by the victim as the voice of her assailant.[2][5] The caller said, "Gonna kill you ... gonna kill you ... gonna kill you ... bitch ... bitch ... bitch ... bitch ... fuckin' whore."[58]

Counseling service (January 6, 1978)

A man claiming to be the East Area Rapist called the Contact Counseling Service and said: "I have a problem. I need help because I don't want to do this anymore." After a short conversation the caller said, "I believe you are tracing this call" and hung up.[2]: 310–315 [136]

Later calls (1982–1991)

In 1982, a previous victim received a call at her place of work — a restaurant — during which the rapist threatened to rape her again. According to Contra Costa County investigator Paul Holes, the rapist must have chanced to patronize the restaurant and recognized his victim there.[137][138]

In 1991, a previous victim received a phone call from the perpetrator and spoke with him for one minute. She could hear a woman and children in the background, leading to speculation that he had a family.[6]

Final call (2001)

On April 6, 2001, one day after an article in the Sacramento Bee linked the Original Night Stalker and the East Area Rapist, a victim of the rapist received a call from him; he asked, "Remember when we played?"[138]

Investigation

Before officially connecting the Original Night Stalker to the East Area Rapist in 2001, some law-enforcement officials (particularly from the Sacramento County Sheriff's Department) sought to link the Goleta cases as well.[139] The links were primarily due to similarities in MO. One of the already-linked Original Night Stalker double murders occurred in Ventura, 40 miles (64 km) southeast of Goleta, and the remaining murders were committed in Orange County, an additional 90 miles (140 km) southeast. In 2001, several rapes in Contra Costa County believed to have been committed by the East Area Rapist were linked by DNA to the Smith, Harrington, Whithuhn, and Cruz murders. A decade later, DNA evidence indicated that the Domingo–Sanchez murders were committed by the Golden State Killer.[2][140][15]

On June 15, 2016, the FBI released further information related to the crimes, including new composite sketches and crime details;[102] a $50,000 reward was also announced.[141] The initiative included a national database to support law enforcement investigating the crimes and handle tips and information.[142] Eventually "through the use of genetic genealogy searching on GEDmatch, investigators identified distant relatives of DeAngelo—including family members directly related to his great- great-great-great grandfather dating back to the 1800s. Based on this information, investigators built about 25 different family trees. The tree that eventually linked to [DeAngelo] alone contained approximately 1,000 people. Over the course of a few months, investigators used other clues like age, sex and place of residence to rule out suspects populating these trees, eliminating suspects one by one until only DeAngelo remained."[15]

During the investigation, several people were considered and later eliminated as suspects:

- Brett Glasby, from Goleta, was considered a suspect by Santa Barbara County investigators. He was murdered in Mexico in 1982, before the murder of Janelle Cruz; this eliminated him as a suspect.[143]

- Paul "Cornfed" Schneider, a high-ranking member of the Aryan Brotherhood, was living in Orange County when the Harringtons, Manuela Witthuhn, and Janelle Cruz were killed. A DNA test cleared him in the 1990s.[144][145]

- Joe Alsip, a friend and business partner of the victim Lyman Smith: Alsip's pastor said that Alsip had confessed to him during a family-counseling session. Alsip was arraigned for the Smith murders in 1982, but the charges were later dropped,[146][147] and his innocence was confirmed by DNA testing in 1997.[148]

On April 24, 2018, Sacramento County Sheriff's deputies arrested DeAngelo.[149] He was charged with eight counts of first-degree murder with special circumstances.[14][150] On May 10, the Santa Barbara County District Attorney's office charged DeAngelo with four additional counts of first-degree murder.[151]

Identification of DeAngelo had begun four months earlier when officials, led by detective Paul Holes and FBI lawyer Steve Kramer, uploaded the killer's DNA profile from a Ventura County rape kit to the personal genomics website GEDmatch.[152] The website identified 10 to 20 people who had the same great-great-great grandparents as the Golden State Killer; a team of five investigators working with genealogist Barbara Rae-Venter used this list to construct a large family tree.[153] From this tree, they established two suspects; one was ruled out by a relative's DNA test, leaving DeAngelo the main suspect.[154]

On April 18, a DNA sample was surreptitiously collected from the door handle of DeAngelo's car,[33] and later another sample was collected from a tissue found in DeAngelo's curbside garbage can.[155] Both were matched to samples associated with Golden State Killer crimes.[18] After DeAngelo's arrest, some commentators have raised concerns about the ethics of the secondary use of personally identifiable information.[156][15]

DeAngelo offered up a confession of sorts after his arrest that cryptically referred to an inner personality named "Jerry" that had apparently forced him to commit the wave of crimes that ended abruptly in 1986. According to Sacramento County prosecutor Thien Ho, DeAngelo said to himself while alone in a police interrogation room after his arrest in April 2018: "I didn’t have the strength to push him out. He made me. He went with me. It was like in my head, I mean, he's a part of me. I didn't want to do those things. I pushed Jerry out and had a happy life. I did all those things. I destroyed all their lives. So now I've got to pay the price."[157]

DeAngelo cannot be charged with rapes or burglaries, as the statute of limitations has expired for those offenses, but he has been charged with 13 counts of murder and 13 counts of kidnapping. DeAngelo was arraigned in Sacramento on August 23, 2018. In November 2018, prosecutors from six involved counties collectively estimated that the case could cost taxpayers $20 million and last 10 years.[158] At an April 10, 2019, court proceeding, prosecutors announced that they would seek the death penalty, and the judge ruled that cameras could be allowed inside the courtroom during the trial.[159][160] On March 4, 2020, DeAngelo offered to plead guilty if the death penalty was taken off the table, which was not accepted at the time. On June 29, DeAngelo pleaded guilty to 13 counts of first-degree murder and special circumstances (including murder committed during burglaries and rapes), as well as 13 counts of kidnapping in a deal to avoid the death penalty.[161][162][163][164]

See also

References

- ^ McNamara, Michelle (February 27, 2013). "The Five Most Popular Myths About the Golden State Killer Case". Los Angeles. Archived from the original on October 20, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Crompton, Larry (August 2, 2010). Sudden Terror. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4520-5241-0.

- ^ a b c d Shelby, Richard (September 15, 2014). Hunting a Psychopath: The East Area Rapist / Original Night Stalker Investigation – The Original Investigator Speaks Out. Booklocker. ISBN 978-1-63263-508-2.

- ^ "Golden State Killer pleads guilty to 13 murders". BBC. June 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i McNamara, Michelle (February 27, 2013). "In the Footsteps of a Killer". Los Angeles. Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2015.; Lange, Jeva (March 19, 2018). "Michelle McNamara's tantalizing roadmap for finding a long lost serial killer". The Week. Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ a b c Hallissy, Erin; Goodyear, Charlie (April 4, 2001). "DNA Links '70s 'East Area Rapist' to Serial Killings / Evidence suggests suspect moved to Southern California". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco, California: Hearst Publishing. Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ^ a b Johnson, Brian (April 27, 2018). "Tulare DA awaits reports connecting 'Golden State Killer' to 'Visalia Ransacker'". ABC30 Fresno. Archived from the original on May 1, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ Fan, Christina (April 26, 2018). "Serial killer's crime spree likely started in Visalia". ABC30 Fresno. Archived from the original on May 4, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "The Original Night Stalker". Cold Case Files. Season 2. Episode 22. May 28, 2000. A&E Networks.

- ^ Thompson, Don (June 15, 2016). "'Original Night Stalker,' active across California, eludes police for 30 years". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Santa Cruz, California: Media News Group. Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 31, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ Hallissy, Erin; Goodyear, Charlie (October 20, 1999). "How DNA Fights Crime/ Other states make better use of technology". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco, California: Hearst Publishing. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ Justice Dept., Federal Bureau of Investigation (April 3, 2017). The FBI Story 2016 (Illustrated ed.). Government Printing Office. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-0-16-093735-4. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ Blankstein, Andrew; Dienst, Jonathan; Siemaszko, Corky (April 25, 2018). "Golden State Killer: Ex-cop arrested in serial murder-rape cold case". NBC News. New York City: NBCUniversal. Archived from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved April 26, 2018.; Stanton, Sam; Egel, Benjy; Lillis, Ryan (April 26, 2018). "Update: East Area Rapist suspect captured after DNA match, authorities say". The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento, California: McClatchy. ISSN 0890-5738. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ a b "Media Advisory – Joseph DeAngelo Charges". Orange County District Attorney. April 25, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Zabel, Joseph (2019). "The Killer Inside Us: Law, Ethics, and the Forensic Use of Family Genetics". Berkeley Journal of Criminal Law. 24 (2).

- ^ Gonzalez, Liz (April 25, 2018). "Police: Golden State Killer is also Visalia Ransacker". Bakersfield Now. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.; Woomer, Eric (April 27, 2018). "Visalia Ransacker suspect was a 'black sheep,' described as a loner in Exeter". Visalia Times. Retrieved April 28, 2018.; Tehee, Joshua (April 25, 2018). "Golden State Killer suspect linked to Visalia mystery, was an Exeter police officer". Fresno Bee. Fresno, California: McClatchy. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ Ford, Matt (September 29, 2016). "After Cosby, California Ends Statute of Limitations on Rape". The Atlantic. Washington, D.C.: Emerson Collective. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Arango, Tim; Goldman, Adam; Fuller, Thomas (April 27, 2018). "To Catch a Killer: A Fake Profile on a DNA Site and a Pristine Sample". The New York Times. New York City: New York Times Company. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ "Golden State Killer suspect arraigned on rape-related charges". NBC News. New York City: NBCUniversal. Retrieved September 18, 2018.; Thompson, Don. "Golden State Killer suspect faces 26 murder and rape-related consolidated charges". The Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois: Tribune Publishing. Retrieved September 18, 2018.

- ^ Jouvnal, Justin. "Man accused of being 'Golden State Killer' enters guilty plea". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C.: Nash Holdings. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ Gabbatt, Adam (June 15, 2020). "'Golden State Killer' suspect reportedly to plead guilty to avoid death penalty". The Guardian. London, England: Guardian Media Group. Reuters. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- ^ Sutton, Candace (June 29, 2018). "Accused serial killer Joseph James DeAngelo's sick words as he raped". News.com.au. Adelaide, Australia: News Corp. Retrieved June 14, 2020.; "Golden State Killer suspect born in Bath". The Evening Tribune. Hornell, New York: Gannett. Associated Press. April 25, 2018.

- ^ Lapin, Tamar (May 14, 2018). "Family of 'Golden State Killer' claim he saw men rape his 7-year-old sister". New York Post. New York City: News Corp.

- ^ a b c d Caraccio, David (May 7, 2018). "What do we know about the life story of the East Area Rapist Suspect". The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento, California: McClatchy.

- ^ a b Egel, Benjy (April 25, 2018). "Who is the East Area Rapist? Police say it's this ex-cop who attended Folsom High". The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento, California: McClatchy. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c Ep. 16 Sgt. Joe DeAngelo, Exeter PD, December 26, 1975, retrieved June 8, 2018

- ^ "Joseph J. DeAngelo expected home on leave from Navy soon". Auburn Journal. Auburn, California: Brehm Communications. June 1, 1967. Archived from the original on April 27, 2018. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ^ a b Ep. 23 They Just Walked Away..., December 26, 1975, retrieved February 5, 2019

- ^ Ross, Martha (April 25, 2018). "Who is Joseph James DeAngelo? Suspect accused in 1979 of stealing a can of dog repellent, hammer". The Mercury News. San Jose, California: Bay Area News Group.

- ^ a b c d KTVU (May 2, 2018), Full Interview: Golden State Killer investigator Paul Holes, retrieved August 13, 2018

- ^ a b Sulek, Julia (April 26, 2018). "'I hate you, Bonnie': Golden State Killer likely motivated by animosity toward ex-fiancee, investigator says". The Mercury News. San Jose, California: MediaNews Group. Archived from the original on May 8, 2018. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ^ "Navy veteran serves Exeter as policeman". Williamsport Sun-Gazette. Williamsport, Pennsylvania: Ogden Newspapers, Inc. August 22, 1973. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c Bowker, Michael (September 28, 2018). "Unsolved Mystery?". Sacramento. Sacramento, California: Hour Media LLC. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- ^ a b Haag, Matthew (April 26, 2018). "What We Know About Joseph DeAngelo, the Golden State Killer Suspect". The New York Times. New York City: New York Times Company. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ California, The State Bar of. "Sharon M Huddle #105101 — Attorney Search". members.calbar.ca.gov. Retrieved August 13, 2018.; "Estranged Wife Of Accused East Area Rapist Filed For Divorce". February 18, 2019.

- ^ St. John, Paige (June 28, 2020). "An inside look at the Golden State Killer suspect's behavior". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California: Tribune Publishing. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ Lillis, Ryan (April 25, 2018). "Here's where East Area Rapist suspect worked for nearly three decades before retiring". The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento, California: McClatchy. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ^ Bonvillain, Crystal. "Golden State Killer suspect was arrested in 1996 Super Bowl ticket ruse – but was released". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia: Cox Media Services.

- ^ Shapiro, Emily; Johnson, Whit; Harrison, Jenna (April 28, 2018). "'Golden State Killer' suspect threatened to kill family dog, yelled and cursed in neighborhood: Neighbors". ABC News. New York City: American Broadcasting Company. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ "A Memorial to the Victims and their Loved Ones". Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c "EAR/BK MASTER TIMELINE" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 1, 2007.

- ^ Clark, Lauren (April 22, 2017). "Connecting the dots in the search for a California serial killer". CBS News. Archived from the original on August 9, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

- ^ Garcia, Natalie (2007). "Retired officer looking to solve 1975 cold case" (PDF). Visalia Times-Delta. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 8, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ Griswold, Lewis (March 4, 2017). "The mystery of the Visalia Ransacker won't go away after 41 years". The Fresno Bee. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ Smith, M.J. (March 25, 2015). "Was Visalia the training ground?". Visalia Times-Delta and Tulare Advance-Register. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ McNamara, Michelle; Oswalt, Patton; Flynn, Gillian (2018). I'll Be Gone in the Dark: One Woman's Obsessive Search for the Golden State Killer. HarperCollins. pp. 88–91. ISBN 978-0-06-231980-7. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 28, 2018.; Ep. 13 VR = EAR?, archived from the original on April 25, 2018, retrieved April 23, 2018

- ^ Large, Steve (February 28, 2018). "East Area Rapist Linked To Rash Of Rancho Cordova Cat Burglaries". Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved June 12, 2018.; Oreskes, Richard Winton, Benjamin (May 11, 2018). "Golden State Killer suspect may be linked to earlier Cordova cat burglar attacks". latimes.com. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); "Story Map Journal". Retrieved June 8, 2018. - ^ Ep. 16 PS Where Are My Pants? | 12-26-75, retrieved June 8, 2018

- ^ "The Visalia Ransacker - Incidents". www.visaliaransacker.com. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ "The Visalia Ransacker". www.visaliaransacker.com. Archived from the original on April 21, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ Ep. 9 The Visalia Ransacker, Part Two, archived from the original on April 25, 2018, retrieved April 21, 2018

- ^ Haagenson, Gene; Courtney, Ricky (April 25, 2018). "Alleged serial killer arrested in Sacramento also known as Visalia Ransacker, officials say". ABC30 Fresno. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ a b "Alleged Golden State Killer to be charged for his very first murder". Global News. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ "Police 'confident' Golden State Killer committed 1975 murder of Claude Snelling". Global News. Retrieved August 13, 2018.; "California district attorney announces 1st degree murder charges against alleged Golden State Killer | Watch News Videos Online". Global News. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ "Man accused of being Golden State Killer pleads guilty to 1975 Visalia murder". KFSN. June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ "Sacramento Is Up Tight Over Rapist and Threats". The Gettysburg Times. Associated Press. May 20, 1977. p. 24. Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ^ "Cold Case EARONS: The Library". Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2017.; "East Area Rapist / Original Night Stalker". East Area Rapist / Original Night Stalker. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ a b c McNamara, Michelle (February 27, 2013). "Hear the Golden State Killer". Los Angeles. Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "Rape fear hovers in Sacramento Valley". Times-Standard. Associated Press. March 25, 1977. p. 22. Archived from the original on October 31, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

The attacks are at a home where no man is present. Either the woman, usually under 35, lives alone, or her husband or family is away.

- ^ Fetherling, Dale (May 22, 1977). "Sacramento Area Rapist Sends Public into Streets". Los Angeles Times. pp. 3, 25. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

; "City in Fear of Rapist's Kill Threat". Indiana Gazette. Associated Press. May 19, 1997. p. 6. Archived from the original on October 31, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

; "City in Fear of Rapist's Kill Threat". Indiana Gazette. Associated Press. May 19, 1997. p. 6. Archived from the original on October 31, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Packer, Bill (November 11, 1977). "Sacramento rapist hits again–27th time in 16 months". Valley News. p. 6. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "$50K reward offered for 'Original Night Stalker' as 40th anniversary nears". The Oregonian. Associated Press. June 15, 2016. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "Suspect in Brutal 1983 Fairfield Murder Commits Suicide After Positive DNA Test". CBS. San Francisco. March 5, 2014. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.; "East Area Rapist Strikes Second Time in Stockton". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. March 20, 1978. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

The rapist spent more than an hour in the house, ransacking it and taking articles of value, police said.

- ^ "Rapist claims 25th victim". Los Angeles Times. UPI. October 22, 1977. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Man Hunted As Suspect in 8 Rapes" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. November 4, 1976. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "East Area Rapist... Fear Grips Serene Neighborhoods" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. November 10, 1976. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ "Rape victim turns tragedy into purpose, with California serial rapist never caught". WSAV. April 7, 2017. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ "Glenbrook Housewife is Raped" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. January 19, 1977. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 5, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "Rapist Strikes Again, 14th time in 15 months" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "East Area Rapist Attacks? 15th Assault" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. February 7, 1977. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 5, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "Lurker Shoots Youth" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. February 17, 1977. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 5, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "Rape May Be Linked to Series" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. March 8, 1977. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 5, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "'East Side Rapist' suspected again" (PDF). The Sacrament Union. March 20, 1977. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 5, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2017.; "Rapist Hits 17th Victim" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. March 20, 1977. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 5, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "18th Rape Victim in East Area" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. April 15, 1977. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ a b "East Area Rapist Attacks 20th Victim in Orangevale" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ Assagai, Mel (May 15, 1977). "East Area Rapist Attacks 22nd Victim at Home" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ "East Area Rapist Attacks No. 23" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. May 17, 1977. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Bell, Ted (May 29, 1977). "East Area Rapist Hits South: Victim 24" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Wayne (September 7, 1977). "Police Certain East Area Rapist Struck in Stockton" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "East Area Rapist Returns to District, Assaults Teen-Aged Girl in Duplex" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. October 2, 1977. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Holloway, Warren; Akeman, Thom (October 21, 1977). "Rapist Gets 25th Victim" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. p. B1–B2. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Mapes, Paul (October 30, 1977). "Couple Terrorized by East Area Rapist" (PDF). The Sacramento Union. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "East Area Rapist Attacks Girl, 13" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. November 10, 1977. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Hammarley, John (December 4, 1977). "Teen-age Boys Scare off Rapist" (PDF). The Sacramento Union. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.; "Noise May Have Curbed Rapist" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. December 4, 1977. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Akeman, Thom (January 30, 1978). "East Rapist Assaults Teen Sisters" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.; "Two sisters latest victims of East Area Rapist". The San Bernardino Sun. Associated Press. January 30, 1978. p. A4. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- ^ "East Rapist in Stockton" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. March 19, 1978. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "East Rapist Kicks in Door, Attacks Sitter in South Area" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. April 16, 1978. pp. A1, A20. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ a b "East Area Rapist Strikes in Modesto" (PDF). The Sacramento Union. June 7, 1978. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "East Area Rapist Strikes Modesto" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. June 7, 1978. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "Rapist Accredited with 2 Attacks" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. June 27, 1978. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Bill (July 7, 1978). "East Area Rapist Returns to Davis, Assaults Mother" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ Assagai, Mel; Diaz, Jaime (October 14, 1978). "Two Concord Rapes in Week Ascribed To East Area Rapist" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 5, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ "Area rapist strikes in Concord" (PDF). The Sacramento Union. October 14, 1978. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 5, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ "Rape's aftermath raises issue of suburban safety" (PDF). Contra Costa Times. December 10, 1978. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.; "Assault in San Ramon Blamed on East Area Rapist" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. November 7, 1978. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.; "East Area Rapist Blamed for attack" (PDF). The Sacramento Union. November 2, 1978. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ a b "Timeline: List of Golden State Killer attacks". The Mercury News. April 25, 2018. Archived from the original on April 30, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ a b "All of the crimes tied to the East Area Rapist/Golden State Killer". NBC KCRA 3. April 25, 2018. Archived from the original on April 30, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ "East Area Rapist Hits in Fremont" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. April 6, 1979. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Fraley, Malaika (July 17, 2011). "Walnut Creek teen rape survivor recalls crime, community's help". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ "Danville Woman Latest Victim of Capital's East Area Rapist" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. June 13, 1979. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "East Area Rapist Attacks 13-Year-Old" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. June 26, 1979. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "East Area Rapist/Original Night Stalker". ear-ons.com. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.; "Cold Case EARONS: The Attacks". Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ a b "Help Us Catch the East Area Rapist". FBI.gov. June 15, 2016. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ^ Mettler, Katie (June 16, 2016). "After 40 years, 12 slayings and 45 rapes, the 'Golden State Killer' still eludes police". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 2, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ Thompson, Don (June 16, 2016). "Reward offered in 40-year-old California serial killer case". Salon. Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "Joseph DeAngelo Pleads Guilty To Killing Brian And Katie Maggiore". sacramento.cbslocal.com/. June 29, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Myers, Joseph Serna, Richard Winton, Sarah Parvini, Melanie Mason, John. "Suspected Golden State Killer, a former police officer, arrested on 'needle in the haystack' DNA evidence". latimes.com. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Sheriff's Blotter" (PDF). Goleta Valley News. October 10, 1979. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ a b Chawkins, Steve; Santa Cruz, Nicole (May 6, 2011). "DNA testing sheds new light on Original Night Stalker case". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ Rimer, Skip; Beamish, Rita (March 17, 1980). "Lawyer, wife found slain in Ventura home" (PDF). Ventura County Star. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.; Thompson, Don (2016). "Reward offered for elusive serial killer with links to Ventura couple". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- ^ a b "$50,000 reward offered in 40-year-old serial killer cold case— four O.C. deaths linked to unknown suspect". Orange County Register. June 15, 2016. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- ^ Alger, Tim (January 3, 1982). "County slayings: Not all cases are closed". Orange County Register. p. B1–B2. Retrieved November 2, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ Scroggin, Samantha (May 6, 2011). "1981 Goleta murders tied to unknown serial killer". Santa Maria Times. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- ^ a b "East Area Rapist/Original Night Stalker". Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ^ a b "Motive and slayer sought in murders". The San Bernardino Sun. Associated Press. January 2, 1980. p. A5. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Slain attorney, wife were beaten to death". The San Bernardino Sun. Associated Press. March 19, 1980. p. A6. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 1, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hurst, John (August 2, 1981). "'Night Stalker' Theory Connecting Eight Southland Slayings Disputed". Los Angeles Times. p. A3, A24. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Barry, Dan; Arango, Tim; Oppel Jr., Richard A. (April 28, 2018). "The Golden State Killer Left a Trail of Horror With Taunts and Guile". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Logan, Dan (October 1988). "Fingering a killer". Orange Coast. 14 (10): 122–128. ISSN 0279-0483. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ^ Leonard, Jack (October 5, 2000). "Victims' Relatives Urge Public to Help Solve Serial Killings". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 24, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c Emery, Sean (May 5, 2009). "'Original Night Stalker' focus of new cable special". Orange County Register. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ Chawkins, Steve; Santa Cruz, Nicole (May 6, 2011). "DNA testing sheds new light on Original Night Stalker case". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2016. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ a b Malnic, Eric (July 29, 1981). "Tie Hinted in Pair of Goleta Murders". Los Angeles Times. p. A20. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Murder 8 & 9 – Cheri Domingo & Greg Sanchez – Night Predator EAR/ONS Files – Goleta, 1981". Archived from the original on June 23, 2016.

- ^ "ONS Attack No. 6". Cold Case: East Area Rapist. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ Macfadyen, William M. (September 7, 2013). "Public's Help Sought with New Clue in 1981 Original Night Stalker Double Murder in Goleta". Noozhawk. Archived from the original on August 26, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ a b Koerner, Claudia (September 10, 2013). "Original Night Stalker: Could O.C. clues lead to killer?". Orange County Register. Anaheim, California: Freedom Communications. Archived from the original on October 31, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ^ Carson-Sandler, Jane; Phelps, M. William (2015). She Survived: Jane. Pinnacle Books. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-7860-3457-4.

- ^ a b c d "Criminal Investigative Analysis" (PDF). A&E. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 7, 2012.

- ^ Locke, Cathy (2017). "Crime Q&A: Any progress in campaign to identify 1970s East Area Rapist?". The Sacramento Bee. ISSN 0890-5738. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ a b Locke, Cathy (September 21, 2013). "Investigators explore new leads in effort to identify East Area Rapist". The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento, California: McClatchy. Archived from the original on October 31, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ Locke, Cathy (February 9, 2018). "Could paint linked to East Area Rapist be traced to companies that sold or used it?". The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento, California: McClatchy. Archived from the original on February 10, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ^ a b "In Brief: Masked Bike Rider Eludes Police". The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento, California: McClatchy. December 12, 1977. Archived from the original on October 31, 2017.

- ^ "Case 53: The East Area Rapist 1978–1979 (Part 4) – Casefile: True Crime". Casefile: True Crime Podcast. June 3, 2017. Archived from the original on March 4, 2018. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- ^ Winters, Kat. "Attack #15". coldcase-earons.com. Archived from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ^ "Case 53: The East Area Rapist – 1976 (Part 1) – Casefile: True Crime". Casefile: True Crime Podcast. May 14, 2017. Archived from the original on March 4, 2018. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- ^ "Letters, Calls, and Sightings from December 1977 to January 1978". Archived from the original on October 17, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ Garcia, Ana (December 12, 2017). "New details released in hunt for 'Golden State Killer'". Crime Watch Daily. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ a b "Pt. 2: New Clue in East Area Rapist Mystery – Crime Watch Daily with Chris Hansen". Crime Watch Daily. Archived from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Wayne (March 13, 1980). "Police Debate Tie Between East Area Rapist, Killings" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento, California: McClatchy. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.; Wilson, Wayne (February 26, 1980). "Link to East Area Rapist Probed in Couples' Slaying" (PDF). The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento, California: McClatchy. p. B1. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Chawkins, Steve (May 5, 2011). "30-year-old slayings of Goleta couple linked to serial killer". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California: Tribune Publishing. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ Piggott, Mark (June 15, 2016). "$50,000 reward for California's 'most prolific' serial killer 30 years on". International Business Times UK. Archived from the original on January 29, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ "FBI Announces $50,000 Reward and National Campaign to Identify East Area Rapist/Golden State Killer". FBI. June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ^ Shelby, Richard (2015). Hunting a Psychopath. St. Petersburg, Florida: Booklocker.com, Inc. pp. 392–393. ISBN 978-1632635082.

- ^ Goodyear, Charlie; Hallissy, Erin (April 25, 2002). "Court says inmate must give DNA / Suspect in 20-year-old murders". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco, California: Hearst Publishing. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ Cason, Colleen (July 3, 2002). "DNA Tests Clear Convict in Ventura Killings Paul Schneider Didn't Kill Attorney Lyman Smith, Wife" (PDF). Ventura County Star. Camarillo, California: Gannett. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- ^ Cason, Colleen (November 28, 2002). "The Silent Witness" (PDF). Ventura County Star. Camarillo, California: Gannett. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- ^ Shelby, Richard (2016). Hunting a Psychopath (Second ed.). Bradenton, Florida: Booklocker.com, Inc. p. 406. ASIN B00P9UP3KS.

- ^ Miller, Aron (October 8, 2000). "DNA Findings Throw New Light on Old Case By" (PDF). Ventura County Star. Camarillo, California: Gannett. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2018.

- ^ Myers, Paul (April 25, 2018). "Sacramento Sheriff's Department arrests Visalia Ransacker, confirms he was an officer of the Exeter Police Department in 1973". The Sun Gazette. Williamsport, Pennsylvania: Ogden Newspapers Inc. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ Fuller, Thomas; Hauser, Christine (April 25, 2018). "Ex-Cop Arrested in Golden State Killer Case: 'We Found the Needle in the Haystack'". The New York Times. New York City: New York Times Company. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 26, 2018.; Egel, Benjy (April 25, 2018). "Who is the East Area Rapist? Police say it's this ex-cop who attended Folsom High". The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento, California: McClatchy. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.; Stanglin, Doug (April 25, 2018). "Golden State Killer: Ex-cop Joseph James DeAngelo arrested as suspect in serial murder-rapes". USA Today. Mclean, Virginia: Gannett. Archived from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ Diskin, Megan (May 10, 2018). "Santa Barbara County DA files charges in murders believed connected to Golden State Killer". Ventura County Star. Camarillo, California: Gannett. Archived from the original on May 17, 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ Stirling, Stephen (April 26, 2018). "How an N.J. pathologist may have helped solve the 'Golden State Killer' case". NJ.com. Archived from the original on May 4, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2018.; Arrango, Tim; Goldman, Adam; Fuller, Thomas (April 27, 2018). "To Catch a Killer: A Fake Profile on a DNA Site and a Pristine Sample". The New York Times. New York City: New York Times Company. Archived from the original on May 2, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2018.; Lillis, Ryan; Kasler, Dale; Chabria, Anita (April 27, 2018). "'Open-source' genealogy site provided missing DNA link to East Area Rapist, investigator says". The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento, California: McClatchy. Archived from the original on April 27, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Murphy, Heather (August 29, 2018). "She Helped Crack the Golden State Killer Case. Here's What She's Going to Do Next". The New York Times. New York City: New York Times Company. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ Jouvenal, Justin (April 30, 2018). "To find alleged Golden State Killer, investigators first found his great-great-great-grandparents". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C.: Nash Holdings. Archived from the original on May 1, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ "Search warrant" (PDF). Sacramento County, California. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 5, 2018. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ Scutti, Susan. "What the Golden State Killer case means for your genetic privacy". CNN. Atlanta, Georgia: Turner Broadcasting Systems. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.; Molteni, Megan (May 27, 2018). "The Creepy Genetics Behind the Golden State Killer Case". Wired. New York City: Condé Nast. Archived from the original on April 27, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "Joseph James DeAngelo Jr. pleads guilty to murders tagged to California's Golden State Killer". USA Today. Mclean, Virginia: Gannett. June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ McDonell-Parry, Amelia; McDonell-Parry, Amelia (December 7, 2018). "Golden State Killer Trial: Joseph DeAngelo Case Could Last 10 Years". Rolling Stone. New York City: Wenner Media. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- ^ "Golden State Killer suspect appears in court nearly one year after arrest". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco, California. April 10, 2019.

- ^ "Golden State Killer One Year Later". CNN. Atlanta, Georgia: Turner Broadcasting Systems. April 24, 2019.

- ^ "Hearing details ghastly crimes of Golden State Killer as he pleads guilty to killings". CNN. Mclean, Virginia: Turner Broadcasting Systems. June 29, 2020.

- ^ "Joseph DeAngelo Pleads Guilty in Golden State Killer Cases". The New York Times. June 29, 2020.

- ^ Kenton, Luke (May 8, 2020). "New documentary tells how an unsolved neighborhood murder in her childhood inspired the late true-crime author Michelle McNamara's journey to unmask the Golden State Killer". MSN. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ "Suspected Golden State Killer seeks plea deal to avoid death penalty". WBTV. March 5, 2020.

Further reading

Literature

- McNamara, Michelle (2018). I'll Be Gone in the Dark: One Woman's Obsessive Search for the Golden State Killer. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-231978-4.

- Shelby, Richard (2015). Hunting a Psychopath: The East Area Rapist / Original Night Stalker Investigation – The Original Investigator Speaks Out. Booklocker. ISBN 978-1-63263-509-9.

- James Huddle (2020). Killers Keep Secrets: The Golden State Killer's Other Life. James N Huddle. ISBN 9781733973205.

- Michael Morford, Michael Ferguson (2018). The Case of the Golden State Killer: Based on the Podcast with Additional Commentary, Photographs and Documents. WildBlue Press. ISBN 978-1947290556.

- Martin G. Welsh (2018). Golden State Killer Book: What Lies Beneath The True Story of the East Area Rapist Psychopath A.K.A. The Night Stalker That Kills In The Dark. Author's Republic. ISBN 9781982727147.

Periodicals

- "Help Us Catch a Killer". Los Angeles. Archived from the original on March 2, 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) (includes numerous photos and maps) - Unmasking a Killer. CNN. A seven-part series that profiles California's most prolific uncaught serial killer.

Podcasts

- 3 Golden State Killer Podcasts That Go Deep on the Case – Time

- Man in the window – Los Angeles Times

- The Creep Among Us – Stitcher

Television

- "The Original Nightstalker". Cold Case Files (Season 2, Episode 22). A&E Television Networks.

- "Golden State Killer: It's Not Over". Golden State Killer: It's Not Over. Investigation Discovery.

- I'll Be Gone in the Dark, an HBO documentary series.

Academic articles

External links

- Full Interview: Golden State Killer investigator Paul Holes — YouTube

- Cold Case – EARONS at coldcase-earons.com

- EAR/ONS magazine – 188-page magazine of related photos and news articles (from Casefile)

- "The Original Nightstalker Map, Part 5a". casefilepodcast.com. Map of the EAR/ONS crimes

- "East Area Rapist / Original Night Stalker". ear-ons.com.

- Map of the East Area Rapist / Original Night Stalker / Golden State Killer Crimes

- True Crime Diary at truecrimediary.com

- Collection of newspaper clippings about the Golden State Killer at Newspapers.com

- Articles to be merged from July 2020

- Golden State Killer

- 1945 births

- 1970s in the United States

- 1975 murders in the United States

- 1978 murders in the United States