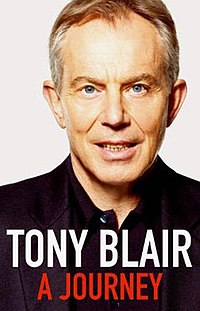

A Journey

| |

| Author | Tony Blair |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Memoir |

| Published | 1 September 2010 Random House |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 624 |

| ISBN | 0-09-192555-X |

| OCLC | 657172683 |

A Journey is a memoir by Tony Blair of his tenure as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Published in the UK on 1 September 2010, it covers events from when he became leader of the Labour Party in 1994 and transformed it into "New Labour", holding power for a party record three successive terms, to his resignation and replacement as Prime Minister by his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown. Blair donated his £4.6 million advance, and all subsequent royalties, to the British Armed Forces charity The Royal British Legion. It became the fastest-selling autobiography of all time at the bookstore chain Waterstones. Promotional events were marked by antiwar protests.

Two of the book's major topics are the strains in Blair's relationship with Brown after Blair allegedly reneged on the pair's 1994 agreement to step down as Prime Minister much earlier, and his controversial decision to participate in the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Blair discusses Labour's future after the 2010 general election, his relations with the Royal Family, and how he came to respect President George W. Bush. Reviews were mixed; some criticised Blair's writing style, but others called it candid.

Gordon Brown was reportedly unhappy over Blair's comments about him, while David Runciman of The London Review of Books suggested there were episodes from Blair's troubled relationship with his Chancellor that were absent from A Journey. Labour politician Alistair Darling said the book demonstrates how the country can be changed for the better when a government has a clear purpose, while the New Zealand Listener suggested Blair and his contemporaries had helped to write New Labour's epitaph. Some families of servicemen and women who were killed in Iraq reacted angrily, with one antiwar commentator dismissing Blair's regrets over the loss of life. Shortly after the release of A Journey, the screenwriter of the 2006 film The Queen, which depicts Blair's first months in office, accused Blair of plagiarising a conversation with Elizabeth II from him.

History

In March 2010, it was reported that Blair's memoirs, under the title The Journey, would be published in September.[1] Gail Rebuck, chairman and chief executive of Random House, announced that the memoirs would be published by Hutchinson in the United Kingdom.[2] She predicted that the book would "break new ground in prime ministerial memoirs just as Blair himself broke the mould of British politics."[1] Preliminary images of the book's cover, showing Blair in an open-neck shirt, were released.[3] In July, the memoir was retitled as A Journey; one publishing expert speculated that it was changed to make Blair appear "less messianic".[3] The publisher did not give any reason.[3] It was announced the book would be published by Knopf in the United States and Canada[4] under the title A Journey: My Political Life;[5] and in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and India by Random House.[4] It was also released as an audiobook, read by Blair[6] available for download and on 13 compact discs with a playing time of 16 hours.[7] The book was published in the United Kingdom on 1 September.[8]

Before the launch, Blair announced that he would give the £4.6m advance and all royalties from his memoirs to a sports centre for injured soldiers.[9][10][11] In an interview with Jonathon Gatehouse, he conceded, "You wouldn't be human if you didn't feel both a sense of responsibility and a deep sadness for those who have lost their lives. That responsibility stays with me now, and will stay with me for the rest of my life. You know, I came to office as prime minister in 1997, focusing on domestic policy and ended up in four conflicts – Sierra Leone, Kosovo, Afghanistan and Iraq. And it does change you, and so it should."[12] BBC political correspondent Norman Smith said Blair's severest critics would see the donation as "guilt money" for taking the UK to war against Iraq in 2003.[11] The father of a soldier killed there decried the donation as "blood money",[11] while the father of another serviceman who died said Blair had a "guilty conscience."[13] A spokesperson for the Stop the War Coalition supported with the donation, but added, "No proportion of Tony Blair's massive and ill-gotten fortune can buy him innocence or forgiveness. He took this country to war on a series of lies against the best legal advice and in defiance of majority opinion."[9] A spokesman for Blair said that it had long been his intention to give the money to a charity; he added aiding soldiers undergoing rehabilitation at the Battle Back Challenge Centre was "his way of honouring their courage and sacrifice."[11] The announcement was welcomed by Chris Simpkins, director general of The Royal British Legion, who said, "Mr Blair's generosity is much appreciated and will help us to make a real and lasting difference to the lives of hundreds of injured personnel."[11]

Synopsis

A Journey covers Blair's time as leader of the Labour Party and then British Prime Minister following his party's victory at the 1997 general election. His tenure as Labour leader begins in 1994 following the death of his predecessor, John Smith, an event Blair claims to have had a premonition about a month before Smith died.[14] Blair believes he will succeed Smith as Labour leader rather than Gordon Brown, who is a strong contender for the job.[14] Blair and Brown subsequently reach an agreement whereby Brown will not run against Blair for the position, and will succeed him later. But it leads to a difficult working relationship, which is discussed at length.[15] He likens them both to "a couple who loved each other, arguing over whose career should come first."[16] To him, Brown is a "strange guy"[17] with "zero" emotional intelligence.[18]

Having been elected as leader Blair moves the Labour Party to the political centre ground, repackaging it as "New Labour", and goes on to win the 1997 general election.[19][20] At his first meeting with Elizabeth II following his election as Prime Minister Blair recalls the Queen telling him, "You are my tenth prime minister. The first was Winston. That was before you were born."[21][22] Within a few months his government must deal with the aftermath of the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, and following the Princess's funeral, Elizabeth II tells Blair that lessons must be learned from the way things have been handled.[23] Social occasions with the Queen are also recalled, including a gathering at Balmoral Castle where Prince Philip is described manning the barbecue while Elizabeth II dons a pair of rubber gloves to wash up afterwards.[24][25]

From the outset Blair's government plays a significant role in the Northern Ireland peace process, during which Blair admits to using "a certain amount of creative ambiguity" to secure an agreement,[26] claiming the process would not have succeeded otherwise. He says that he stretched the truth "on occasions past breaking point" in the run-up to the 2007 power-sharing deal which enabled the return of devolved legislative powers from Westminster to the Northern Ireland Executive.[27] Both Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness of Sinn Féin are praised for the part they played in the peace process.[27]

One of the themes that dominates the latter part of Blair's time in office is his decision to join US President George W. Bush in committing troops to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the aftermath of which he describes as a "nightmare",[28] but that he believes to have been necessary because Saddam Hussein "had not abandoned the strategy of WMD [weapons of mass destruction], merely made a tactical decision to put it into abeyance".[29] He would make the same decision again with regard to Iran, warning that if that country develops nuclear weapons it will change the balance of power of the Middle East, to the region's detriment.[30] Blair believes some problems in Iraq still require a "resolution" and will fester if left unattended.[31] Of the war dead he says, "I feel desperately sorry for them, sorry for the lives cut short, sorry for the families whose bereavement is made worse by the controversy over why their loved ones died, sorry for the utterly unfair selection that the loss should be theirs."[32] A year on from the invasion he hopes Bush will win a second term as US President:[33] "I had come to like and admire George," he writes.[34]

In 2003, Blair promises his Chancellor, Gordon Brown that he will resign before the next general election, but later changes his mind.[35] Brown subsequently attempts to blackmail him, threatened to call for a Labour Party inquiry into the 2005 Cash for Honours affair during an argument over pension policy.[36][37] Brown succeeds Blair as Labour Party leader and Prime Minister in 2007. But while Blair praises Brown as a good Chancellor and a committed public servant, he believes his decision to abandon the New Labour policies of the Blair years leads to the party's 2010 election defeat.[18] However, Brown is right to restructure British banks and introduce an economic stimulus after the financial crisis.[34]

The book closes with a final chapter offering a critique of Labour Party policy, and discusses its future. Blair warns Brown's successor that if Labour is to remain electable they should continue with the policies of New Labour and not return to the left-wing policies of the 1980s:[38] "I won three elections. Up to then, Labour had never even won two successive full terms. The longest Labour government had lasted six years. This lasted 13. It could have gone on longer, had it not abandoned New Labour."[28]

Publication

Within hours of its launch A Journey became the fastest-selling autobiography of all time at bookseller Waterstones,[39] where it sold more copies in one day than Peter Mandelson's The Third Man: Life at the Heart of New Labour had done in its first three weeks earlier that year.[40] It debuted at the top of Amazon.co.uk's British best-seller list.[39] Within a week, Nielsen BookScan said that 92,000 copies of A Journey had been sold in the United Kingdom, the best opening week for an autobiography since the company began keeping figures in 1998.[41] The New York Times reported that in the United States, an initial print run of 50,000 copies had been extended by another 25,000, with the book set to debut at Number 3 on The New York Times hardcover best-seller list.[42] Andrew Lake, Waterstones' political buyer, said, "Nothing can compare to the level of interest shown in this book. You have to look at hugely successful fiction authors such as Dan Brown or JK Rowling to find books that have sold more quickly on their first day. Mandelson may remain the prince but Blair has reclaimed his title as king, certainly in terms of book sales.[43]

Blair recorded a series of promotional interviews for radio and television for, among others, the Arabic television network Al Jazeera, the ITV1 daytime magazine programme This Morning,[43] and BBC Two, which aired an hour-long interview with the journalist and political commentator Andrew Marr.[44] He was in Washington, D.C. on the day of the UK launch to participate in peace talks with Middle East leaders and attend a White House dinner with Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Israeli and Palestinian leaders.[45][46] The British newspaper The Independent reported that Blair's visit to the United States was a coincidence, and not an attempt to be out of the United Kingdom when the book was published.[43] When Blair arrived for his first book signing at a leading bookshop on O'Connell Street, Dublin on 4 September, demonstrators heckled, jeered and threw eggs and shoes at him. One activist posed as a purchaser to attempt a citizen's arrest of Blair for war crimes.[47][48][49] Protestors clashed with Irish police and tried to push over a security barrier outside the shop. The demonstrators—anti-war protestors and Irish republicans opposed to the peace process—called queuing customers "traitors" and "West Brits".[47] Four people were arrested during the incident.[48]

Several days after the launch of the book, Blair appeared on the series premiere of ITV1's breakfast television programme Daybreak, where he criticised the Dublin protestors as a small minority given undue media attention. Since the book was selling well, and given fears that protesters would also be present at a forthcoming book signing in London on 8 September, he expressed doubts over whether that event was justifiable or worth the inevitable disruption.[50] Later in the day it was confirmed the signing at Waterstones in Piccadilly would not go ahead.[51][52] A spokesman for Blair announced that a planned launch party for the book scheduled for the Tate Modern would take place despite plans by the Stop the War Coalition to demonstrate.[53] However, the following day this event was also cancelled as a result of threats of disruption by campaigners.[54] In subsequent weeks, a number of media organisations reported that copies of A Journey were being moved from autobiographical sections in bookshops to sections on crime and horror.[55][56][57] More than 10,000 people had joined a Facebook page calling for that action.[55][56]

Reception

In the United Kingdom

A Journey drew a mixed reception from critics. Financial Times editor Lionel Barber called it "part psychodrama, part treatise on the frustrations of leadership in a modern democracy ... written in a chummy style with touches of Mills & Boon". He wrote that it made Blair seem "likable, if manipulative; capable of dissembling while wonderfully fluent; in short, a brilliant modern politician (whatever his moans about the media)."[58] Writing in The Independent on Sunday, Geoffrey Beattie said A Journey offered an understanding of Blair's "underlying psychology."[59] John Rentoul, author of the Blair biography Tony Blair Prime Minister, was equally positive, giving particular praise to the chapter on the Iraq War. "The chapter on Iraq is tightly argued in some detail, which may persuade those with open minds to recognise that the decision to join the US invasion was a reasonable, if not very successful, one, rather than a conspiracy against life, the universe and everything decent," he said.[60] Mary Ann Sieghart, writing for The Independent said, "whatever its faults, and toe-curling passages, [A Journey] has many good lessons on how to succeed in both opposition and government.[61]

Other reviewers were less positive. The political journalist and author Andrew Rawnsley was critical of Blair's writing style in The Observer. "It is Tony Blair's boast that he wrote every word in longhand 'on hundreds of notepads'. That I believe," he wrote. "He was the most brilliant communicator of his era as a platform speaker or television interviewee, but he can be a ghastly writer. Anyone thinking about taking this journey needs to be given a travel advisory: much of the prose is execrable ... I could say that it is a pity that Tony Blair did not employ a ghostwriter to prettify the prose and organise his recollections more elegantly." Rawnsley does, though, praise the book as being "a more honest political memoir than most and more open in many respects than I had anticipated."[62] Julian Glover, a columnist in The Guardian, said that "no political memoir has ever been like this: a book written as if in a dream—or a nightmare; a literary out-of-body experience. By turns honest, confused, memorable, boastful, fitfully endearing, important, lazy, shallow, rambling and intellectually correct, it scampers through the last two decades like a trashy airport read."[63] The Sunday Telegraph was extremely critical of Blair's writing style. "If Blair wants to tell you a funny story, he makes the mistake of signalling in advance that you should be laughing—what happened was 'hilarious', his first weekend at Balmoral was 'utterly freaky'—thereby strangling the anecdote at birth. The book, like its author, is slightly embarrassing."[64] In the journal History Today, Archie Brown, Emeritus Professor of Politics at Oxford University was critical of what he believed to be Blair's flawed sense of leadership, but had praise for the chapter on the Northern Ireland peace process: "Blair's role in the Northern Ireland settlement was perhaps his single most noteworthy achievement. His account of it is also the best chapter in a book which, even by the standards of memoirists who fancy themselves to be remarkable leaders, is strikingly egocentric."[65]

In the United States

Reviews in the US sounded similar themes. In The New Yorker, British novelist John Lanchester called A Journey "a detailed account of scrambling, scraping, horse-trading, bluffing, and fudging the way to a deal—a remarkable combination of the ramshackle and the historic."[66] Fareed Zakaria of The New York Times Book Review praised Blair for his openness in the publication. "When speaking about the challenges of his first term in office, Blair writes honestly and openly," the newspaper said. "The style is not the elegant Oxbridge prose that might have been expected of a former prime minister but one filled with Americanisms. It is breezy, informal and candid enough to keep the reader thoroughly engaged."[67] However, Zakaria attacked Blair's "sweeping generalizations" about terrorism.[67]

Writing in The Washington Post, Leonard Downie, Jr., former editor of that paper, called the work a "notably wistful memoir" and is generally positive about its content: "Toward the end of this well-written and perhaps unintentionally self-revealing memoir, Tony Blair, who was Britain's prime minister during an eventful decade from 1997 to 2007, insists he is 'trying valiantly not to fall into self-justifying mode—a bane of political memoirs.' But he has done just that."[68] Tim Rutton of the Los Angeles Times also gave the memoirs a favourable review, declaring it "a political biography of unusual interest."[69]

Internationally

There are fewer reviews from newspapers outside the United Kingdom and United States, but those available are generally positive. Writing for Australia's The Sydney Morning Herald Alexander Downer, who served as Foreign Minister in the Government of John Howard gave A Journey a favourable review: "His [Blair's] commitment to humanity is sincere and convincing, and his personality infectiously amiable with a delightful sense of self-deprecating humour."[70] Konrad Yakabuski, a senior political writer for Canada's The Globe and Mail was also positive: "If Tony Blair has not continued to agonize over the tough decisions of his prime ministership, he does a pretty good job of persuading otherwise in A Journey."[71] India's English language daily The Hindu said of the book, "It is by no means a confessional memoir but a brave attempt with only patchy success at self-justification."[72]

Political reaction

The Queen reportedly felt a "profound sense of disappointment" in Blair for breaking with protocol by revealing in his memoirs sensitive details of private conversations he had with her during his time as Prime Minister.[a] A spokesman for Buckingham Palace told a newspaper, "No prime minister before has ever done this and we can only hope that it will never happen again."[73] The Sunday Express claimed, quoting "renowned Royal biographer Hugo Vickers" and other "Royal insiders", that because of the book's contents, Elizabeth II would withhold granting Blair the Order of the Thistle, an honour which is bestowed at the sovereign's personal prerogative and normally given almost automatically to leaders of Scottish descent after leaving office.[74] Gordon Brown was said to be "seething" and "dismayed" over the criticism he received from Blair in the book, but had told aides not to criticise it.[75] Ed Balls, a Brown ally who served in his government as Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families said, "It would have been much better if the memoirs had been a celebration of success rather than recriminations. In that sense I thought it was all a bit sad. It was so one-sided. I didn't think it was comradely."[75]

Several more of Blair's former colleagues and political opponents also commented on the book. Former Conservative minister Norman Tebbit wrote in The Daily Telegraph, "A Journey seems to be dominated by Blair's anxiety to be seen as a great political leader who changed his country for the better. In fact it is, as I suppose all such books are to some extent, entirely about justifying himself and blaming others." However, Tebbit admitted he had not read the book at the time of writing about it and based his opinion on media coverage.[76] Writing in The Guardian, Alistair Darling, who was Chancellor under Gordon Brown, said that he "read with wry amusement how Tony Blair felt after much agonising that he couldn't sack his Chancellor. History has a habit of repeating itself." He concluded that the book was "a good read and shows us what can be done when we have confidence, clarity and a clear sense of purpose: we can win and change the country for the better."[77] Labour Member of Parliament Tom Harris said that the book "will be a reminder that opposition doesn't have to be permanent, and that great things can be accomplished by a Labour government, but only if we have a leader capable of appealing to voters beyond our own party's core." Of Blair, he said, "There are still many, many Labour Party members who remember Blair as an election-winning genius who, in office, was popular for an awful lot longer than he was unpopular."[78] Ed Miliband, then vying for the vacant position of Labour Party leader, said on the day of publication, "I think it is time to move on from Tony Blair and Gordon Brown and Peter Mandelson and to move on from the New Labour establishment and that is the candidate that I am at this election who can best turn the page. I think frankly most members of the public will want us to turn the page."[78] He was elected as Leader of the Labour Party several weeks later.[79]

Some families of servicemen and servicewomen who were killed in Iraq reacted angrily to the book, in which Blair does not apologise for the invasion.[80][81] "I can't regret the decision to go to war. I can say never did I guess the bloody, destructive and chaotic nightmare that unfolded—and that too is part of the responsibility," he says in the book.[80] Reg Keys, whose son Tom Keys was killed in Iraq in 2003, said that the book was "just crocodile tears from Blair."[80] Keys said, "The tears he claims to have shed are nothing like the tears I and my wife have shed for our son. They are nothing like the tears that tens of thousands of Iraqis have shed for their loved ones. They don't even come close to it. They seem to me like crocodile tears. It is a cynical attempt to sanitise his legacy."[82] A spokesperson for Military Families Against the War said that Blair's expression of regret over the loss of life was "completely meaningless." The spokesperson added, "He has to prove his regret and giving money to charity doesn't come close. He is giving a minuscule amount compared to the cost of war and rehabilitation of injured soldiers. It is laughable."[80][81]

Some of the dialogue Blair uses to describe his first meeting with Elizabeth II led to accusations of plagiarism from Peter Morgan, who wrote The Queen, set during the first few months of Blair's premiership. Blair recalls his first meeting with Elizabeth II in which she tells him, "You are my 10th prime minister. The first was Winston. That was before you were born." In the film, Helen Mirren's fictionalised Elizabeth II says almost exactly the same thing.[83][84] Morgan said it had been purely his own imagination.[83]

Other accounts of the Blair years

Some commentators offered comparisons between A Journey and accounts of the Blair years written by other senior members of his government, particularly on Blair's relationship with Gordon Brown. David Goodhart of Prospect Magazine wrote that in both Peter Mandelson's memoir The Third Man and the first volume of Alastair Campbell's Diaries (1994–97), "Blair is important, but a rather weak figure buffeted by events and by Gordon Brown. In Blair's own account, A Journey (in which Mandelson features hardly at all, and Gordon Brown only at the end) it is of course very different. Almost everything is driven forward by him; the new Labour project was not imminent in Britain's political history—it had to be shaped and moulded."[85] A similar theme was echoed by David Runciman in The London Review of Books, where he reflected that Mandelson's memoirs "provide a much more complete account of the Blair/Brown relationship", including details of Operation Teddy Bear, an aborted plot from 2003 to curb Brown's increasing influence as Chancellor by dividing the Treasury to create a separate Office of Budget and Delivery that would be controlled directly by the Cabinet Office.[86]

Writing for the journal British Politics, academic Mark Garnett provided a detailed analysis of the Blair and Mandelson memoirs, observing that while A Journey gives a more in-depth account of what he termed "contemporary British government", The Third Man is a more satisfying read: "The Third Man was a worthwhile effort for Peter Mandelson's reputation, while Tony Blair has journeyed in vain."[87] The New Zealand Listener, on the other hand, suggested that A Journey and other memoirs written by prominent architects of New Labour had helped to seal its doom after David Miliband – the preferred candidate of all three as Brown's successor – failed to be elected to the position: "All three backed David Miliband, and however much Miliband tried to distance himself – I'm not New Labour, I'm Next Labour – these three books and the publicity that surrounded them showed he had New Labour dye all over his hands. David was beaten to the leadership by his younger brother, Ed (a man who lacked, as Blair himself might put it, the New Labour baggage), by a whisker – just over 1%. And at a stroke, it's clear these great, vocal proselytisers of New Labour have unwittingly written its epitaph."[88]

Notes

References

- ^ a b "'Frank' Blair memoirs out in September". The Bookseller. Bookseller Media Ltd. 4 March 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ^ "Tony Blair's memoir, The Journey, to be published in September". The Office of Tony Blair. 4 March 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ^ a b c Booth, Robert (12 July 2010). "Tony Blair's memoirs title change strikes a less 'messianic' tone". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "People outside the UK". The Office of Tony Blair. Archived from the original on 7 January 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "A Journey: My Political Life; Hardcover". Random House. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ^ "A Journey: My Political Life; Audiobook". Random House. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ^ Tony Blair A Journey audiobook on at Toronto Public Library. Retrieved 9 March 2014

- ^ Flood, Alison (1 September 2010). "Tony Blair's A Journey is hot ticket at booksellers". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ a b Taylor, Matthew (16 August 2010). "Tony Blair pledges book proceeds to Royal British Legion". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Give Tony Blair credit for a truly magnanimous gesture". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. 16 August 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e "Tony Blair donates book cash to injured soldier charity". BBC News. BBC. 16 August 2010. Archived from the original on 16 August 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gatehouse, Jonathon (13 September 2010). "Tony Blair in Conversation with Jonathon Gatehouse". Maclean's. 123 (35): 16–18. ISSN 0024-9262.

- ^ Barnett, Ruth (16 August 2010). "Blair's Book Donation Branded 'Blood Money'". Sky News. British Sky Broadcasting. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ a b Chapman, James (2 September 2010). "The love affair that soured: How mistrust and betrayal tore Blair and Brown apart". Daily Mail. Associated Newspapers Ltd. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ Chapman, James (2 September 2010). "The love affair that soured: How mistrust and betrayal tore Blair and Brown apart". Daily Mail. Associated Newspapers Ltd. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ Hutton, Robert (1 September 2010). "Blair Backs Cameron Program, Slams 'Strange' Brown". Bloomberg Businessweek. Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Blair takes shot at 'strange guy' Gordon Brown". ABC News. American Broadcasting Company. 2 September 2010. Archived from the original on 8 November 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Blake, Heidi (1 September 2010). "Tony Blair: Gordon Brown had 'zero' emotional intelligence". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ Toynbee, Polly; Freedland, Jonathan; Clark, Tom; White, Michael (1 September 2010). "Tony Blair's memoirs: verdict". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ Assinder, Nick (2 September 2010). "Blair's Memoirs Tell of Buddying Up to Bush and Ignoring Brown's Calls". Time Magazine. Time Warner. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ Shackle, Samira (9 September 2010). "Is Blair confusing fiction with reality?". New Statesman. Progressive Digital Media. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ "No royal honour for Tony Blair, Queen upset by revelations in memoir". NDTV. New Delhi Television Ltd. 5 September 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ "Princess Diana's death was 'global event' says Blair". BBC News. BBC. 1 September 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ Mount, Harry (1 September 2010). "Tony Blair shouldn't be surprised by the Queen's traditional upper-class manners". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ "Queen's fury at tell tale Tony Blair". Daily Express. Northern and Shell Media. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ Gordon, David (4 September 2010). "Tony Blair: Northern Ireland peace is an inspiration to the world". Belfast Telegraph. Independent News and Media. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ a b Rutherford, Adrian; McAdam, Noel (2 September 2010). "Tony Blair blasted as 'naive' for praising Sinn Féin leaders". Belfast Telegraph. Independent News and Media. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ a b Grice, Andrew (1 September 2010). "Finally Tony Blair reveals his side of the feud with Gordon Brown". The Independent. Independent Print Ltd. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ "Would Saddam have rebuilt his WMD?". BBC News. BBC. 14 September 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ Shipman, Tim (2 September 2010). "How Blair was seconds from ordering RAF to shoot down passenger plane over London after 9/11". Daily Mail. Associated Newspapers Ltd. Archived from the original on 9 November 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Pidd, Helen; Hill, Amelia; Sparrow, Andrew; Bowcott, Owen; Norton-Taylor, Richard; Watt, Nicholas (1 September 2010). "Tony Blair memoirs: Sex, war, Carole Caplin and George Bush". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ "Tony Blair A Journey: key quotes". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. 1 September 2010. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hohmann, James (3 September 2010). "Blair rooted for Bush to win in '04". Politico. Allbritton Communications Company. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ a b Edwards, Tim (1 September 2010). "Tony Blair's A Journey: the highlights". The First Post. Dennis Publishing. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ "Blair 'broke promise to Brown not to run a third time'". BBC News. BBC. 14 July 2010. Archived from the original on 3 November 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Maddox, David (2 September 2010). "Tony Blair memoirs: Blackmail and skulduggery at the heart of government". The Scotsman. Johnston Press. Archived from the original on 12 October 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mulholland, Hélène (1 September 2010). "Tony Blair: Gordon Brown 'tried to blackmail me over cash-for-honours'". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 7 November 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jamieson, Alastair (1 September 2010). "Tony Blair memoirs: former PM on the Labour leadership contest". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ a b "Tony Blair: A Journey tops best-seller list". Metro. Associated Newspapers Ltd. 3 September 2010. Archived from the original on 14 October 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Tony Blair's A Journey breaks sales records". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. 2 September 2010. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Stone, Philip (7 September 2010). "Blair defies protests with record-breaking first week". The Bookseller. Bookseller Media Ltd. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ Lyall, Sarah (8 September 2010). "Blair Memoir a Hit, Despite a Few Hard Knocks". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Grice, Andrew (2 September 2010). "Blair's memoirs: From No10 to No1". The Independent. Independent Print Ltd. Archived from the original on 4 September 2010. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Deans, Jason (2 September 2010). "TV ratings: Tony Blair takes 1.8 million on journey on BBC2". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 2 September 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ McGreal, Chris (2 September 2010). "Middle East peace talks begin in Washington". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 2 November 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Tony Blair's Memoir Hits Bookstores". Fox News. News Corporation. 1 September 2010. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- ^ a b McDonald, Henry (4 September 2010). "Tony Blair pelted with eggs and shoes at book signing". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 8 September 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Howie, Michael (4 September 2010). "Four men arrested after shoes and eggs are thrown at Tony Blair at book signing". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Archived from the original on 7 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Johnson, Andrew; McConnell, Daniel (5 September 2010). "Blair roadshow attracts his foes – and some fans". The Independent. Independent Print Ltd. Archived from the original on 6 September 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hugh, Andrew (6 September 2010). "Tony Blair memoirs: former PM may cancel book signing amid security fears". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Archived from the original on 7 September 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Tony Blair cancels book signing amid protest fears". BBC News. BBC. 6 September 2010. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- ^ Topping, Alexandra (6 September 2010). "Tony Blair scrapped London book signing to avoid protest 'hassle'". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 8 September 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Blair's 'secret' launch party to go ahead despite protests". The Bookseller. Bookseller Media Ltd. 7 September 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ Mulholland, Hélène (8 September 2010). "Tony Blair book launch party cancelled". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 11 September 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Pearse, Damien (4 September 2010). "Blair Book's Journey To Crime Section". Sky News. British Sky Broadcasting. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ^ a b Battersby, Matilda (8 September 2010). "Tony Blair's journey to the crime section". The Independent. Independent Print Ltd. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ^ Topping, Alexandra (5 September 2010). "Looking for Tony Blair's memoir? Try the crime section". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 10 October 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Barber, Lionel (3 September 2010). "Tony Blair: A Journey". Financial Times. Pearson PLC. Archived from the original on 4 September 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Beattie, Geoffrey (5 September 2010). "Inside the mind of Tony Blair". The Independent on Sunday. Independent Print Ltd. Archived from the original on 6 September 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rentoul, John (3 September 2010). "A Journey, By Tony Blair". The Independent. Independent Print Ltd. Archived from the original on 4 September 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sieghart, Mary Ann (6 September 2010). "Blair has much to teach his successors". The Independent. Independent Print Ltd. Archived from the original on 9 September 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rawnsley, Andrew (5 September 2010). "Tony Blair's A Journey: Andrew Rawnsley's verdict". The Observer. Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 6 September 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Glover, Julian (1 September 2010). "Tony Blair: He can still make us believe – and then, pages later, feel sick". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 7 November 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Moore, Charles (12 September 2010). "Journey by Tony Blair: review". Sunday Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Archived from the original on 26 October 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Brown, Archie (January 2011). "Tony Blair: The whole world in his hands". History Today. 61 (1). History Today Ltd: 44–45. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Lanchester, John (13 September 2010). "The Which Blair Project". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ a b Zakaria, Fareed (8 October 2010). "The Convert". The New York Times Book Review. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Downie, Jr., Leonard (5 September 2010). "Tony Blair's fierce defense of his political life". Washington Post. The Washington Post Company. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ Rutten, Tim (2 September 2010). "A Journey My Political Life | Book Review: 'A Journey: My Political Life'". Los Angeles Times. Tribune Company. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ Downer, Alexander (1 October 2010). "Tony Blair: A Journey". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ Yakabuski, Konrad (11 September 2010). "Book Review: Blair, Tony: A Journey: My Political Life". The Globe and Mail. The Globe and Mail Inc. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Bhadrakumar, M. M. (11 January 2011). "Blair has a story for Indians". The Hindu. Kasturi and Sons Ltd. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ a b Walker, Tim (3 September 2010). "The Queen is not amused by Tony Blair's indiscretions". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Archived from the original on 6 September 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Giannangell, Marco (5 September 2010). "Queen's snub to Tony Blair by withholding Honour". Sunday Express. Northern and Shell Media. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ^ a b Grice, Andrew (3 September 2010). "'Seething' Brown claims moral high ground – but will not attack his old ally". The Independent. Independent Print Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 September 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Tebbit, Norman (6 September 2010). "Tony Blair didn't save the Labour Party: he crucified it, and this country". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 7 September 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Darling, Alistair (11 September 2010). "A Journey by Tony Blair". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ a b Sparrow, Andrew (1 September 2010). "Tony Blair's A Journey memoir released – live blog". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 26 November 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Grice, Andrew (10 June 2011). "Follow my lead or Labour is finished, Blair tells Miliband". The Independent. Independent Print Ltd. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d Lyons, James (1 September 2010). "Tony Blair memoirs blasted by soldiers families for 'crocodile tears' over Iraq". Daily Mirror. Trinity Mirror. Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Baldie, Jonathan (12 September 2010). "Long awaited Blair memoirs provoke protests". The Journal. The Edinburgh Journal Ltd. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ^ Pidd, Helen (1 September 2010). "Tony Blair memoirs: A Journey sparks anger at 'self pity and mockery'". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ^ a b Walker, Tim (8 September 2010). "Peter Morgan accuses Tony Blair of plagiarising lines from his film The Queen". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Archived from the original on 9 September 2010. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Itzkoff, David (8 September 2010). "In Blair Memoir, Is It the Queen or 'The Queen'?". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Goodhart, David (27 October 2010). "The leader we deserved". Prospect Magazine. Prospect Publishing. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ Runciman, David (7 October 2010). "Preacher on a Tank". London Review of Books. Nicholas Spice. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ Garnett, Mark (2011). "Cash for quotations: The memoirs of Peter Mandelson and Tony Blair". British Politics. 6. Palgrave Macmillan: 397–404. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Manhire, Toby (16 October 2010). "Journey's end". New Zealand Listener. APN News and Media. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

External links