Arrow

An arrow is a shafted projectile that is shot with a bow. It predates recorded history and is common to most cultures. An arrow usually consists of a shaft with an arrowhead attached to the front end, with fletchings and a nock at the other.

History

The oldest evidence of stone-tipped projectiles, which may or may not have been propelled by a bow (c.f. atlatl), dating to c. 64,000 years ago, were found in Sibudu Cave, South Africa.[1] The oldest evidence of the use of bows to shoot arrows dates to about 10,000 years ago; it is based on pinewood arrows found in the Ahrensburg valley north of Hamburg. They had shallow grooves on the base, indicating that they were shot from a bow.[2] The oldest bow so far recovered is about 8,000 years old, found in the Holmegård swamp in Denmark. Archery seems to have arrived in the Americas with the Arctic small tool tradition, about 4,500 years ago.

Size

Arrow sizes vary greatly across cultures, ranging from eighteen inches to five feet (45 cm to 150 cm).[3] However, most modern arrows are 75 centimetres (30 in) to 96 centimetres (38 in); most war arrows from an English ship sunk in 1545 were 76 centimetres (30 in).[4] Very short arrows have been used, shot through a guide attached either to the bow (an "overdraw") or to the archer's wrist (the Turkish "siper").[5] These may fly farther than heavier arrows, and an enemy without suitable equipment may find himself unable to return them.

Shaft

The shaft is the primary structural element of the arrow, to which the other components are attached. Traditional arrow shafts are made from lightweight wood, bamboo or reeds, while modern shafts may be made from aluminium, carbon fibre reinforced plastic, or a combination of materials. Such shafts are typically made from an aluminium core wrapped with a carbon fibre outer.

The stiffness of the shaft is known as its spine, referring to how little the shaft bends when compressed. Hence, an arrow which bends less is said to have more spine. In order to strike consistently, a group of arrows must be similarly spined. "Center-shot" bows, in which the arrow passes through the central vertical axis of the bow riser, may obtain consistent results from arrows with a wide range of spines. However, most traditional bows are not center-shot and the arrow has to deflect around the handle in the archer's paradox; such bows tend to give most consistent results with a narrower range of arrow spine that allows the arrow to deflect correctly around the bow. Higher draw-weight bows will generally require stiffer arrows, with more spine (less flexibility) to give the correct amount of flex when shot.

GPI rating

The weight of an arrow shaft can be expressed in GPI (Grains Per Inch).[6] The length of a shaft in inches multiplied by its GPI rating gives the weight of the shaft in grains. For example, a shaft that is 30 inches long and has a GPI of 9.5 weighs 285 grains, or about 18 grams. This does not include the other elements of a finished arrow, so a complete arrow will be heavier than the shaft alone.

Footed arrows

Sometimes a shaft will be made of two different types of wood fastened together, resulting in what is known as a footed arrow. Known by some as the finest of wood arrows,[7] footed arrows were used both by early Europeans and Native Americans. Footed arrows will typically consist of a short length of hardwood near the head of the arrow, with the remainder of the shaft consisting of softwood. By reinforcing the area most likely to break, the arrow is more likely to survive impact, while maintaining overall flexibility and lighter weight.

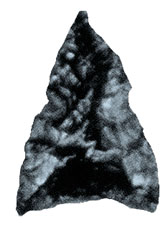

Arrowhead

The arrowhead or projectile point is the primary functional part of the arrow, and plays the largest role in determining its purpose. Some arrows may simply use a sharpened tip of the solid shaft, but it is far more common for separate arrowheads to be made, usually from metal, horn, or some other hard material. Arrowheads are usually separated by function:

- Bodkin points are short, rigid points with a small cross-section. They were made of unhardened iron and may have been used for better or longer flight, or for cheaper production. It has been mistakenly suggested that the bodkin came into its own as a means of penetrating armour, but research[8] has found no hardened bodkin points, so it is likely that it was first designed either to extend range or as a cheaper and simpler alternative to the broadhead. In a modern test, a direct hit from a hard steel bodkin point penetrated Damascus chain armour.[9] However, archery was not effective against plate armour, which became available to knights of fairly modest means by the late 14th century.[10]

- Blunts are unsharpened arrowheads occasionally used for types of target shooting, for shooting at stumps or other targets of opportunity, or hunting small game when the goal is to stun the target without penetration. Blunts are commonly made of metal or hard rubber. They may stun, and occasionally, the arrow shaft may penetrate the head and the target; safety is still important with blunt arrows.

- Judo points have spring wires extending sideways from the tip. These catch on grass and debris to prevent the arrow from being lost in the vegetation. Used for practice and for small game.

- Broadheads were used for war and are still used for hunting. Medieval broadheads could be made from steel,[8] sometimes with hardened edges. They usually have two to four sharp blades that cause massive bleeding in the victim. Their function is to deliver a wide cutting edge so as to kill as quickly as possible by cleanly cutting major blood vessels, and cause further trauma on removal. They are expensive, damage most targets, and are usually not used for practice.

There are two main types of broadheads used by hunters: The fixed-blade and the mechanical types. While the fixed-blade broadhead keeps its blades rigid and unmovable on the broadhead at all times, the mechanical broadhead deploys its blades upon contact with the target, its blades swinging out to wound the target. The mechanical head flies better because it is more streamlined, but has less penetration as it uses some of the kinetic energy in the arrow to deploy its blades.[11][citation needed]

- Field tips are similar to target points and have a distinct shoulder, so that missed outdoor shots do not become as stuck in obstacles such as tree stumps. They are also used for shooting practice by hunters, by offering similar flight characteristics and weights as broadheads, without getting lodged in target materials and causing excessive damage upon removal.

- Target points are bullet-shaped with a conical point, designed to penetrate target butts easily without causing excessive damage to them.

- Safety arrows are designed to be used in various forms of reenactment combat, to reduce the risk when shot at people. These arrows may have heads that are very wide or padded. In combination with bows of restricted draw weight and draw length, these heads may reduce to acceptable levels the risks of shooting arrows at suitably armoured people. The parameters will vary depending on the specific rules being used and on the levels of risk felt acceptable to the participants. For instance, SCA combat rules require a padded head at least 11⁄4" in diameter, with bows not exceeding 28 inches (710 mm) and 50 lb (23 kg) of draw for use against well-armoured individuals.[12]

Arrowheads may be attached to the shaft with a cap, a socketed tang, or inserted into a split in the shaft and held by a process called hafting.[3] Points attached with caps are simply slid snugly over the end of the shaft, or may be held on with hot glue. Split-shaft construction involves splitting the arrow shaft lengthwise, inserting the arrowhead, and securing it using a ferrule, sinew, or wire.[13]

Fletchings

Fletchings are found at the back of the arrow and act as airfoils to provide a small amount of force used to stabilize the flight of the arrow. They are designed to keep the arrow pointed in the direction of travel by strongly damping down any tendency to pitch or yaw. Some cultures, for example most in New Guinea, did not use fletching on their arrows.[14] Also, arrows without fletching (called bare shaft) are used for training purposes, because they make certain errors by the archer more visible.[15]

Fletchings are traditionally made from feathers (often from a goose or turkey) bound to the arrow's shaft, but are now often made of plastic (known as "vanes"). Historically, some arrows used for the proofing of armour used copper vanes.[16] Flight archers may use razor blades for fletching, in order to reduce air resistance. With conventional three-feather fletching, one feather, called the "cock" feather, is at a right angle to the nock, and is normally nocked so that it will not contact the bow when the arrow is shot. Four-feather fletching is usually symmetrical and there is no preferred orientation for the nock; this makes nocking the arrow slightly easier.

Artisans who make arrows by hand are known as "fletchers," a word related to the French word for arrow, flèche. This is the same derivation as the verb "fletch", meaning to provide an arrow with its feathers. Glue and/or thread are the main traditional methods of attaching fletchings. A "fletching jig" is often used in modern times, to hold the fletchings in exactly the right orientation on the shaft while the glue hardens.

Whenever natural fletching is used, the feathers on any one arrow must come from the same wing of the bird. The most common being the right-wing flight feathers of turkeys. The slight cupping of natural feathers requires them to be fletched with a right-twist for right wing, a left-twist for left wing. This rotation, through a combination of gyroscopic stabilization and increased drag on the rear of the arrow, helps the arrow to fly straight away.[17] Artificial helical fletchings have the same effect. Most arrows will have three fletches, but some have four or even more. Fletchings generally range from two to six inches (152 mm) in length; flight arrows intended to travel the maximum possible distance typically have very low fletching, while hunting arrows with broadheads require long and high fletching to stabilize them against the aerodynamic effect of the head. Fletchings may also be cut in different ways, the two most common being parabolic (i.e. a smooth curved shape) and shield (i.e. shaped as one-half of a very narrow shield) cut.

In modern archery with screw-in points, right-hand rotation is generally preferred as it makes the points self-tighten. In traditional archery, some archers prefer a left rotation because it gets the hard (and sharp) quill of the feather farther away from the arrow-shelf and the shooter's hand.[18]

A flu-flu is a form of fletching, normally made by using long sections of full length feathers taken from a turkey, in most cases six or more sections are used rather than the traditional three. Alternatively two long feathers can be spiraled around the end of the arrow shaft. The extra fletching generates more drag and slows the arrow down rapidly after a short distance, about 30 m or so [citation needed].

Flu-Flu arrows are often used for hunting birds, or for children's archery, and can also be used to play Flu-Flu Golf.

Nocks

The nock is a notch in the rearmost end of the arrow. It serves to keep the arrow in place on the string as the bow is being drawn. Nocks may be simple slots cut in the back of the arrow, or separate pieces made from wood, plastic, or horn that are then attached to the end of the arrow.[19] Modern nocks, and traditional Turkish nocks, are often constructed so as to curve around the string or even pinch it slightly, so that the arrow is unlikely to slip off.[20] In English it is common to say "nock an arrow" when one readies a shot.

In Arab archery, there was the description of the use of "nockless arrows". In shooting at the enemies, either the Turks or the Persians, it was seen that the enemies would pick up the expended arrows and shoot them back at the Arabs. So they developed "nockless arrows", which would be useless to their foes. The bowstring would have a small ring that is tied onto the string at the proper point where the nock would normally be placed. The end of the arrow, rather than being slit for a nock, would be sharpened like an arrowhead, then the rear end of the arrow would be slipped into this ring and drawn and released as usual. Then the enemy could collect all the arrows it wanted, but they would be useless to them in shooting back. A piece of battle advice was to have several rings tied onto the bowstring in case one broke.[21]

See also

- Archery

- Arrow poison

- Bowfishing

- Early thermal weapons

- Fire arrows

- Flechette

- Flu-Flu Arrow

- Quarrel

- Signal arrow

- Swiss arrow

Notes

- ^ Lyn Wadley from the University of the Witwatersrand (2010); BBC: Oldest evidence of arrows found

- ^ McEwen E, Bergman R, Miller C. Early bow design and construction. Scientific American 1991 vol. 264 pp76-82.

- ^ a b Stone, George Cameron (1934). A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration, and Use of Arms and Armor in All Countries and in All Times, Mineola: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-40726-8

- ^ Anon: The Mary Rose; Armament p.7

- ^ Turkish Archery and the Composite Bow. Paul E. Klopsteg ISBN 1-56416-093-9 ISBN 978-1564160935

- ^ GPI explained by an arrow vendor (referred to from their listing of carbon arrows)

- ^ Langston, Gene (1994). "Custom Shafts". The Traditional Bowyer's Bible - Volume Three. Guilford: The Lyons Press. ISBN 1-58574-087-X.

- ^ a b Royal Armouries: 6. Armour-piercing arrowheads

- ^ Hunting with the Bow and Arrow, by Saxton Pope. https://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext05/8hbow10.txt "To test a steel bodkin pointed arrow such as was used at the battle of Cressy, I borrowed a shirt of chain armor from the Museum, a beautiful specimen made in Damascus in the 15th Century. It weighed twenty-five pounds and was in perfect condition. One of the attendants in the Museum offered to put it on and allow me to shoot at him. Fortunately, I declined his proffered services and put it on a wooden box, padded with burlap to represent clothing. Indoors at a distance of seven yards (6 m), I discharged an arrow at it with such force that sparks flew from the links of steel as from a forge. The bodkin point and shaft went through the thickest portion of the back, penetrated an inch of wood and bulged out the opposite side of the armor shirt. The attendant turned a pale green. An arrow of this type can be shot about two hundred yards, and would be deadly up to the full limit of its flight."

- ^ Strickland M, Hardy R. The Great Warbow. Sutton Publishing 2005. Page 272

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-09-25. Retrieved 2010-02-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ SCA marshall's handbook

- ^ Parker, Glenn (1992). "Steel Points". The Traditional Bowyer's Bible - Volume Two. Guilford: The Lyons Press. ISBN 1-58574-086-1.

- ^ Gardens of War: Life and Death in the New Guinea Stone Age. Robert Gardner. Deutsch 1969. ISBN 0-233-96140-2, ISBN 978-0-233-96140-8

- ^ Stonebraker, Rick (2000). "Tune for Tens". texasarchery.org. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

WHY A BARE SHAFT? If shot at short distance through paper into a butt, a bare shaft will reveal improper thrust effects since aerodynamics will not have time to straighten out the flight of the arrow. It will literally fly sideways through the paper creating a tell-tale pattern if the tune is bad. Fletching would straighten out the arrow's flight and make this first stage of tuning more difficult.

- ^ Ffoulkes, Charles (1988) [1912]. The Armourer and his Craft (Dover reprint ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-25851-3.

- ^ "Carbon Arrow University". www.huntersfriend.com. Retrieved 2016-04-22.

- ^ "Traditional Bow Selection Guide". www.huntersfriend.com. Retrieved 2016-04-22.

- ^ Massey, Jay(1992). "Self Arrows" in The Traditional Bowyer's Bible - Volume One, Guilford: The Lyons Press. ISBN 1-58574-085-3

- ^ Stone, G.C. "A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration and Use of Arms and Armor"

- ^ Faris, Nabih Amin, and Robert Potter Elmer. Chapter XLIV. "On Stunt Shooting." IN: Arab archery. An Arabic manuscript of about A.D. 1500, "A book on the excellence of the bow & arrow" and the description thereof. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1945. Pages 131-132.