Aspiration pneumonia

| Aspiration pneumonia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Microscopic image of aspiration pneumonia in an elderly person with a neurologic illness. Note foreign-body giant cell reaction. | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine, pulmonology |

| Symptoms | Fever, cough[1] |

| Complications | Lung abscess and pneumonia[1] |

| Usual onset | Elderly[2] |

| Risk factors | Decreased level of consciousness, problems with swallowing, alcoholism, tube feeding, poor oral health[1] |

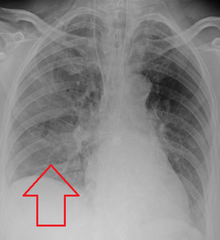

| Diagnostic method | Based on presenting history, symptoms, chest X-ray, sputum culture[2][1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Chemical pneumonitis, tuberculosis[1][2] |

| Medication | Clindamycin, meropenem, ampicillin/sulbactam, moxifloxacin[1] |

| Frequency | ~10% of pneumonia cases requiring hospitalization[1] |

Aspiration pneumonia is a type of lung infection that is due to a relatively large amount of material from the stomach or mouth entering the lungs.[1] Signs and symptoms often include fever and cough of relatively rapid onset.[1] Complications may include lung abscess, acute respiratory distress syndrome, empyema, and parapneumonic effusion.[3][1] Some include chemical induced inflammation of the lungs as a subtype, which occurs from acidic but non-infectious stomach contents entering the lungs.[1][2]

Infection can be due to a variety of bacteria.[2] Risk factors include decreased level of consciousness, problems with swallowing, alcoholism, tube feeding, and poor oral health.[1] Diagnosis is typically based on the presenting history, symptoms, chest X-ray, and sputum culture.[1][2] Differentiating from other types of pneumonia may be difficult.[1]

Treatment is typically with antibiotics such as clindamycin, meropenem, ampicillin/sulbactam, or moxifloxacin.[1] For those with only chemical pneumonitis, antibiotics are not typically required.[2] Among people hospitalized with pneumonia, about 10% are due to aspiration.[1] It occurs more often in older people, especially those in nursing homes.[2] Both sexes are equally affected.[2]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Signs and symptoms of aspiration pneumonia may develop gradually, with increased respiratory rate, foul-smelling sputum, hemoptysis, and fever. Complications may occur, such as exudative pleural effusion, empyema, and lung abscesses.[4] If left untreated, aspiration pneumonia can progress to form a lung abscess.[5] Another possible complication is an empyema, in which pus collects inside the lungs.[6] If continual aspiration occurs, the chronic inflammation can cause compensatory thickening of the insides of the lungs, resulting in bronchiectasis.[6]

Causes

[edit]Most aspiration events occur in patients with a defective swallowing mechanism, such as a neurological disease or as the result of an injury that directly impairs swallowing or interferes with consciousness.[7] Impaired consciousness can be intentional, such as the use of general anesthesia for surgery. For many types of surgical operations, people preparing for surgery are therefore instructed to take nothing by mouth (nil per os, abbreviated as NPO) for at least four hours before surgery. These conditions enable the entry of bacteria into the lungs, thus allowing the development of an infection.[citation needed]

Risk factors

[edit]- Impaired swallowing: Conditions that cause dysphagia worsen the ability of people to swallow, causing an increased risk of entry of particles from the stomach or mouth into the airways. While swallowing dysfunction is associated with aspiration pneumonia, dysphagia may not be sufficient unless other risk factors are present.[4] Neurologic conditions that can directly impact the nerves involved in the swallow mechanism include stroke, neurodegenerative diseases (such as Parkinson's disease), and multiple sclerosis.[1] Anatomical changes in the chest can also disrupt the swallow mechanism.[1] For example, patients with advanced COPD tend to develop enlarged lungs, resulting in compression of the esophagus and thus regurgitation.[1]

- Altered mental status: Changes in levels of consciousness affect the swallow mechanism by both disabling the body's natural protective measures against aspiration as well as possibly causing nausea and vomiting.[1] Altered mental status can be caused by medical conditions such as seizures.[1] However, many other agents can be responsible as well, including general anesthesia and alcohol.[1]

- Bacterial colonization: Poor oral hygiene can result in colonization of the mouth with excessive amounts of bacteria, which is linked to increased incidence of aspiration pneumonia.[1]

- Ethnicity: Asians diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia have a lower risk of death compared to other ethnic groups while African Americans and whites share a relatively similar risk of death. Hispanics have a lower risk of death than non-Hispanics.[8]

- Others: Age, male sex, diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, use of antipsychotic drugs, proton pump inhibitors, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.[9] Residence in an institutional setting, prolonged hospitalization or surgical procedures, gastric tube feeding,[10] mechanical airway interventions, immunocompromised, history of smoking, antibiotic therapy, advanced age, reduced pulmonary clearance, diminished cough reflex, disrupted normal mucosal barrier, impaired mucociliary clearance, alter cellular and humoral immunity, obstruction of the airways, and damaged lung tissue.[11]

Bacteria

[edit]Bacteria involved in aspiration pneumonia may be either aerobic or anaerobic.[12] Common aerobic bacteria involved include:

- Streptococcus pneumoniae[13]

- Staphylococcus aureus[13]

- Haemophilus influenzae[13]

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa[13]

- Klebsiella: often seen in aspiration lobar pneumonia in alcoholics

Anaerobic bacteria also play a key role in the pathogenesis of aspiration pneumonia.[14] They make up the majority of normal oral flora and the presence of putrid fluid in the lungs is highly suggestive of aspiration pneumonia secondary to an anaerobic organism.[14] While it is difficult to confirm the presence of anaerobes through cultures, the treatment of aspiration pneumonia typically includes anaerobic coverage regardless.[14] Potential anaerobic bacteria are as follows:

Pathophysiology

[edit]Aspiration is defined as inhalation of oropharyngeal or gastric contents into the pulmonary tree. Depending on the composition of the aspirate, three complications have been described:[4]

- Chemical pneumonitis may develop whose severity depends on the pH value and quantity of aspirate. The two lung changes after acid aspiration are: a) direct toxic damage to the respiratory epithelium resulting in interstitial pulmonary edema and b) a few hours later, inflammatory response with production of cytokines, neutrophil infiltration, and macrophage activation. Oxygen-free radicals are generated which, in turn, lead to further lung damage. Patients may remain asymptomatic after acid aspiration. Others may develop dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, cough, fever, bloody or frothy sputum, and respiratory failure.

- Aspiration pneumonia may develop.

- The third complication occurs after inhalation of particulate matter that obstructs airways. The patients will have sudden arterial hypoxemia with development of lung atelectasis.

Location

[edit]The location is often gravity dependent, and depends on the person's position. Generally, the right middle and lower lung lobes are the most common sites affected, due to the larger caliber and more vertical orientation of the right mainstem bronchus. People who aspirate while standing can have bilateral lower lung lobe infiltrates. The right upper lobe is a common area of consolidation, where liquids accumulate in a particular region of the lung, in alcoholics who aspirate in the supine position.[15]

Diagnosis

[edit]

Evaluation of aspiration is generally performed with a video fluoroscopic swallowing study involving radiologic evaluation of the swallowing mechanism via challenges with liquid and solid food consistencies. These studies allow for evaluation of penetration to the vocal folds and below but are not a sensitive and specific marker for aspiration.[16] Additionally, it is difficult to distinguish between aspiration pneumonia and aspiration pneumonitis.[17]

Aspiration pneumonia is typically diagnosed by a combination of clinical circumstances (people with risk factors for aspiration) and radiologic findings (an infiltrate in the proper location).[1] A chest x-ray is typically performed in cases where any pneumonia is suspected, including aspiration pneumonia.[18] Findings on chest x-ray supportive of aspiration pneumonia include localized consolidation depending on the patient's position when the aspiration occurred.[18] For example, people that are supine when they aspirate often develop consolidation in the right lower lobe of the lung.[18] Sputum cultures are not used for diagnosing aspiration pneumonia because of the high risk of contamination.[19] Clinical symptoms may also increase suspicion of aspiration pneumonia, including new difficulty breathing and fever after an aspiration event.[6] Likewise, physical exam findings such as altered breath sounds heard in the affected lung fields may also be suggestive of aspiration pneumonia.[6] Some cases of aspiration pneumonia are caused by aspiration of food particles or other particulate substances like pill fragments; these can be diagnosed by pathologists on lung biopsy specimens.[20]

While aspiration pneumonia and chemical pneumonitis may appear similar, it is important to differentiate between the two due to major differences in management of these conditions. Chemical pneumonitis is caused by damage to the inner layer of lung tissue, which triggers an influx of fluid.[19] The inflammation caused by this reaction can rapidly cause similar findings seen in aspiration pneumonia, such as an elevated WBC (white blood cell) count, radiologic findings, and fever.[19] However, it is important to note that the findings of chemical pneumonitis are triggered by inflammation not caused by infection, as seen in aspiration pneumonia. Inflammation is the body's immune response to any perceived threat to the body. Thus, treatment of chemical pneumonitis typically involves removal of the inflammatory fluid and supportive measures, notably excluding antibiotics.[21] The use of antimicrobials is reserved for chemical pneumonitis complicated by secondary bacterial infection.[19]

Prevention

[edit]There have been several practices associated with decreased incidence and decreased severity of aspiration pneumonia as detailed below.

Oral hygiene

[edit]Studies showed that the net reduction of oral bacteria was associated with a decrease in both incidence of aspiration pneumonia as well as mortality from aspiration pneumonia.[22] One broad method of decreasing the number of bacteria in the mouth involves the use of antimicrobials, ranging from topical antibiotics to intravenous antibiotic use.[22] Whereas the use of antibiotics focuses on destroying and hindering the growth of bacteria, mechanical removal of oral bacteria by a dental professional also plays a key role in reducing the bacterial burden.[22] By reducing the amount of bacteria in the mouth, the likelihood of infection when aspiration occurs is reduced as well.[22] For people who are critically ill that require a feeding tube, there is evidence suggesting that the risk of aspiration pneumonia may be reduced by inserting the feeding tube into the duodenum or the jejunum (post-pyloric feeding), when compared to inserting the feeding tube into the stomach.[10]

Enhanced swallow

[edit]Many people at risk for aspiration pneumonia have an impaired swallowing mechanism, which may increase the chance of aspiration of food particles with meals.[22] There is some evidence to indicate that training of various parts of the body involved in the act of swallowing, including the tongue and lips, may reduce episodes of aspiration and aspiration pneumonia; however, further research is required to confirm this benefit.[22] Other simple actions during feeding can improve the swallowing capability of a person and thus reduce the risk of aspiration, including changes in position and feeding assistance.[23]

After surgery

[edit]Many instances of aspiration occur during surgical operations, especially during anesthesia induction.[24] The administration of anesthesia causes suppression of protective reflexes, most importantly the gag reflex. As a result, stomach particles can easily enter the lungs. Certain risk factors predispose individuals to aspiration, especially conditions causing dysfunction of the upper gastrointestinal system.[24] Identifying these conditions before the operation begins is essential for proper preparation during the procedure.[24] It is recommended that patients fast prior to procedures as well.[24] Other practices that may be beneficial but have not been well-studied include medication that reduce the acidity of gastric contents and rapid sequence induction.[24] On the other hand, regarding reducing acidity of the stomach, an acid environment is needed to kill the organisms that colonize the gastrointestinal tract; agents, such as proton pump inhibitors, that decrease the acidity of the stomach, may favor the growth of bacteria and increase the risk of pneumonia.[4]

Treatment

[edit]Adjusting the patient's posture should come first, then the oropharyngeal contents should be suctioned with the nasogastric tube in place. Humidified oxygen is given to patients who are not intubated, and the head end of the bed should be elevated by 45 degrees. It's crucial to keep a close eye on the patient's oxygen saturation, and if hypoxia is detected, urgent intubation with mechanical breathing should be given. Flexible bronchoscopy is often used to gather samples of bronchoalveolar lavage for quantitative bacteriological tests as well as high volume aspiration to clear the secretion.[25] In general practice The main treatment of aspiration pneumonia revolves around the use of antibiotics to remove the bacteria causing the infection.[1] Broad antibiotic coverage is required to account for the diverse types of bacteria possibly causing the infection.[1] Even though they are not necessary in cases with aspiration pneumonitis, antibiotics are typically started right away to stop the disease's development.[citation needed] Recommended antibiotics include clindamycin, meropenem, ertapenem, ampicillin/sulbactam, and moxifloxacin.[1] Treatment with piperacillin/tazobactam, cefepime, levofloxacin, imipenem, or meropenem is recommended in cases of potential antibiotic resistance.[26] The typical duration of antibiotic therapy is about 5 to 7 days.[26] If there is a large accumulation of fluid within the lungs, drainage of the fluid may also aid in the healing process.[14]

Prognosis

[edit]Dysphagia clinicians often recommend alteration of dietary regimens, altered head positioning, or removal of all oral intake. While studies have suggested that thickening liquids can decrease aspiration through slowed pharyngeal transit time, they have also demonstrated increased pharyngeal residues with risk for delayed aspiration. The ability of clinical interventions to reduce pneumonia incidence is relatively unknown. Dietary modifications or nothing-by-mouth status also have no effect on a patient's ability to handle their own secretions. A patient's individual vigor may impact the development of pulmonary infections more than aspiration. Also increased pneumonia risk exists in patients with esophageal dysphagia when compared to stroke patients because patients with stroke will improve as they recover from their acute injury, whereas esophageal dysphagia is likely to worsen with time. In one cohort of aspiration pneumonia patients, overall three-year mortality was 40%.[16]

Studies have shown that aspiration pneumonia has been associated with an overall increased in-hospital mortality as compared with other forms of pneumonia.[27] Further studies investigating differing time spans including 30-day mortality, 90-day mortality, and 1-year mortality.[27] Individuals diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia were also at increased risk of developing future episodes of pneumonia. In fact, these individuals were also found to be at higher risk for readmission after being discharged from the hospital.[27] Lastly, one study found that individuals diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia were more likely to fail treatment compared to other types of pneumonia.[27]

Elderly

[edit]Aging increases the risk of dysphagia. The prevalence of dysphagia in nursing homes is approximately 50%, and 30% of the elderly with dysphagia develop aspiration. For individuals older than 75, the risk of pneumonia due to dysphagia is six times greater than those 65.[28] Owing to multiple factors, such as frailty, impaired efficacy of swallowing, decreased cough reflex and neurological complications, dysphagia can be considered as a geriatric syndrome.[29] Atypical presentation is common in the elderly. Older patients may have impaired T cell function and hence, they may be unable to mount a febrile response. The mucociliary clearance of older people is also impaired, resulting in diminished sputum production and cough. Therefore, they can present non-specifically with different geriatric syndromes.[4]

Microaspirations

[edit]In the elderly, dysphagia is a significant risk factor for the development of aspiration pneumonia. Aspiration pneumonia most often develops due to micro-aspiration of saliva, or bacteria carried on food and liquids, in combination with impaired host immune function.[30] Chronic inflammation of the lungs is a key feature in aspiration pneumonia in elderly nursing home residents and presents as a sporadic fever (one day per week for several months). Radiological review shows chronic inflammation in the consolidated lung tissue, linking chronic micro-aspiration and chronic lung inflammation.

Choking

[edit]After falls, choking on food presents as the second highest cause of preventable death in aged care.[30] Although food choking risk is commonly associated with young children, data shows that individuals over 65 years of age have a choking incidence that is seven times higher than children aged 1–4 years.[30]

Parkinson's disease

[edit]The reported prevalence of dysphagia in patients with Parkinson's disease ranges from 20% to 100% due to variations in the methods of assessing the swallowing function.[31] Unlike some medical problems, such as stroke, dysphagia in Parkinson's Disease degenerates with disease progression. Aspiration pneumonia was the most common reason for the emergency admission of patients with Parkinson's Disease whose disease duration was >5 years and pneumonia was one of the main causes of death.

Dementia

[edit]The familiar model of care for people with advanced dementia and dysphagia is the revolving door of recurrent chest infections, frequently associated with aspiration and related readmissions. Many individuals with dementia resist or are indifferent to food and fail to manage the food bolus. There are also many contributory factors such as poor oral hygiene, high dependency levels for being positioned and fed, as well as the need for oral suctioning. While tube feeding might therefore be considered a safer option, tube feeding has not been shown to be beneficial in people with advanced dementia. The preferred option therefore is to continue eating and drinking orally despite the risk of developing chest infections.[28]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa DiBardino DM, Wunderink RG (February 2015). "Aspiration pneumonia: a review of modern trends". Journal of Critical Care. 30 (1): 40–8. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.07.011. PMID 25129577.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ferri, Fred F (2017). "Pneumonia, Aspiration". Ferri's Clinical Advisor. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1006. ISBN 978-0-323-52957-0.

- ^ Sanivarapu, Raghavendra R.; Gibson, Joshua (2023). "Aspiration Pneumonia". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. NBK470459.

- ^ a b c d e Luk JK, Chan DK (Jul 2014). "Preventing aspiration pneumonia in older people: do we have the 'know-how'?". Hong Kong Med J. 20 (5): 421–7. doi:10.12809/hkmj144251. PMID 24993858.

- ^ Kemp, Burns & Brown 2007, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b c d Deterding et al. 2016, p. [page needed].

- ^ Delegge, M. H. (2002). "Aspiration pneumonia: Incidence, mortality, and at-risk populations". Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 26 (6 Suppl): S19-24, discussion S24-5. doi:10.1177/014860710202600604. PMID 12405619.

- ^ Oliver MN, Stukenborg GJ, Wagner DP, Harrell FE, Kilbridge KL, Lyman JA, Einbinder J, Connors AF (November 2004). "Comorbid disease and the effect of race and ethnicity on in-hospital mortality from aspiration pneumonia". Journal of the National Medical Association. 96 (11): 1462–9. PMC 2568617. PMID 15586650.

- ^ van der Maarel-Wierink CD, Vanobbergen JN, Bronkhorst EM, Schols JM, de Baat C (June 2011). "Risk factors for aspiration pneumonia in frail older people: a systematic literature review". Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 12 (5): 344–54. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2010.12.099. PMID 21450240.

- ^ a b Alkhawaja S, Martin C, Butler RJ, Gwadry-Sridhar F (August 2015). "Post-pyloric versus gastric tube feeding for preventing pneumonia and improving nutritional outcomes in critically ill adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (8): CD008875. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008875.pub2. PMC 6516803. PMID 26241698.

- ^ Taylor GW, Loesche WJ, Terpenning MS (2000). "Impact of oral diseases on systemic health in the elderly: diabetes mellitus and aspiration pneumonia". Journal of Public Health Dentistry. 60 (4): 313–20. doi:10.1111/j.1752-7325.2000.tb03341.x. PMID 11243053.

- ^ Son YG, Shin J, Ryu HG (March 2017). "Pneumonitis and pneumonia after aspiration". Journal of Dental Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 17 (1): 1–12. doi:10.17245/jdapm.2017.17.1.1. PMC 5564131. PMID 28879323.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Table 13-7 in: Mitchell RS, Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology: With Student Consult Online Access (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ^ a b c d Bartlett JG (March 2013). "How important are anaerobic bacteria in aspiration pneumonia: when should they be treated and what is optimal therapy". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 27 (1): 149–55. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2012.11.016. PMID 23398871.

- ^ Aspiration Pneumonitis and Pneumonia at eMedicine

- ^ a b Bock M, Varadarajan V, Brawley M, Blumin J (2017). "Evaluation of the Natural History of Patients Who Aspirate". Laryngoscope. 127 (8): S1–S10. doi:10.1002/lary.26854. PMC 5788193. PMID 28884823.

- ^ Lanspa M, Peyrani P, Wiemkwn T, Wilson E, Ramirez J, Dean N (2015). "Characteristics associated with clinician diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia; a descriptive study of afflicted patients and their outcomes". J Hosp Med. 10 (2): 90–6. doi:10.1002/jhm.2280. PMC 4310822. PMID 25363892.

- ^ a b c McKean et al. 2016, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b c d Kasper et al. 2015, p. [page needed].

- ^ Mukhopadhyay S, Katzenstein AL (May 2007). "Pulmonary disease due to aspiration of food and other particulate matter: a clinicopathologic study of 59 cases diagnosed on biopsy or resection specimens". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 31 (5): 752–9. doi:10.1097/01.pas.0000213418.08009.f9. PMID 17460460. S2CID 45207101.

- ^ Fishman et al. 2015, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b c d e f Tada A, Miura H (July 2012). "Prevention of aspiration pneumonia (AP) with oral care". Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 55 (1): 16–21. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2011.06.029. PMID 21764148.

- ^ Conant et al. 2014, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b c d e Nason KS (August 2015). "Acute Intraoperative Pulmonary Aspiration". Thoracic Surgery Clinics. 25 (3): 301–7. doi:10.1016/j.thorsurg.2015.04.011. PMC 4517287. PMID 26210926.

- ^ Son, Y. G.; Shin, J.; Ryu, H. G. (2017). "Pneumonitis and pneumonia after aspiration". Journal of Dental Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 17 (1): 1–12. doi:10.17245/jdapm.2017.17.1.1. PMC 5564131. PMID 28879323.

- ^ a b Mandell, Lionel A.; Niederman, Michael S. (14 February 2019). "Aspiration Pneumonia". New England Journal of Medicine. 380 (7): 651–663. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1714562. PMID 30763196. S2CID 73428526.

- ^ a b c d Komiya K, Rubin BK, Kadota JI, Mukae H, Akaba T, Moro H, Aoki N, Tsukada H, Noguchi S, Shime N, Takahashi O, Kohno S (December 2016). "Prognostic implications of aspiration pneumonia in patients with community acquired pneumonia: A systematic review with meta-analysis". Scientific Reports. 6: 38097. Bibcode:2016NatSR...638097K. doi:10.1038/srep38097. PMC 5141412. PMID 27924871.

- ^ a b Hansjee, Djaromee (2018). "An Acute Model of Care to Guide Eating & Drinking Decisions in the Frail Elderly with Dementia and Dysphagia". Geriatrics. 3 (4): 65. doi:10.3390/geriatrics3040065. PMC 6371181. PMID 31011100.

- ^ Hollaar V, Putten G, Maarel-Wierink C, Bronkhorst E, Swart B, Creugers N (2017). "The effect of a daily application of a 0.05% chlorhexidine oral rinse solution on the incidence of aspiration pneumonia in nursing home residents: a multicenter study". BMC Geriatrics. 17 (128): 128. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0519-z. PMC 5477106. PMID 28629318.

- ^ a b c Cichero, Julie (2018). "Age-Related Changes to Eating and Swallowing Impact Frailty: Aspiration, Choking Risk, Modified Food Texture and Autonomy of Choice". Geriatrics. 3 (4): 69–79. doi:10.3390/geriatrics3040069. PMC 6371116. PMID 31011104.

- ^ Umemoto G, Furuya H (2019). "Management of Dysphagia in Patients with Parkinson's Disease and Related Disorders". Intern Med. 59 (1): 7–14. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.2373-18. PMC 6995701. PMID 30996170.

Sources

[edit]- Conant, Rebecca; Williams, Brie; Chen, Helen; Landefeld, C. Seth; Ahalt, Cyrus; Chang, Anna (2014). Current Diagnosis and Treatment: Geriatrics (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-179208-0.

- Deterding, Robin R.; Hay, William W.; Levin, Myron J.; Abzug, Mark J. (2016). Current Diagnosis and Treatment Pediatrics, Twenty-Third Edition. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-184854-1.

- Fishman, Jay A.; Kotloff, Robert; Grippi, Michael A.; Pack, Allan I.; Senior, Robert M.; Elias, Jack A. (2015). Fishman's Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-180728-9.

- Kasper, Dennis L.; Jameson, J. Larry; Hauser, Stephen L.; Loscalzo, Joseph; Fauci, Anthony S.; Longo, Dan L. (2015). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (19th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-180215-4.

- Kemp, William; Burns, Dennis; Brown, Travis (2007). Pathology: The Big Picture. Mcgraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-147748-2.

- McKean, Sylvia C.; Ross, John J.; Dressler, Daniel D.; Scheurer, Danielle (2016). Principles and Practice of Hospital Medicine (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-184313-3.