Bechdel test

The Bechdel test (/ˈbɛkdəl/ BEK-dəl),[1] also known as the Bechdel–Wallace test,[2] is a measure of the representation of women in fiction. It asks whether a work features at least two women who talk to each other about something other than a man. The requirement that the two women must be named is sometimes added.[3]

According to user-edited databases and the media industry press, about half of all films meet these criteria. Passing or failing the test is not necessarily indicative of how well women are represented in any specific work. Rather, the test is used as an indicator for the active presence of women in the entire field of film and other fiction, and to call attention to gender inequality in fiction. Media industry studies indicate that films that pass the test perform better financially than those that do not.

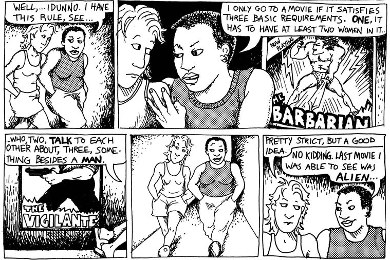

The test is named after the American cartoonist Alison Bechdel, in whose 1985 comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For the test first appeared. Bechdel credited the idea to her friend Liz Wallace and the writings of Virginia Woolf. After the test became more widely discussed in the 2000s, a number of variants and tests inspired by it emerged.

History

Gender portrayal in popular fiction

In her 1929 essay A Room of One's Own, Virginia Woolf observed about the literature of her time what the Bechdel test would later highlight in more recent fiction:[4]

All these relationships between women, I thought, rapidly recalling the splendid gallery of fictitious women, are too simple. ... And I tried to remember any case in the course of my reading where two women are represented as friends. ... They are now and then mothers and daughters. But almost without exception they are shown in their relation to men. It was strange to think that all the great women of fiction were, until Jane Austen's day, not only seen by the other sex, but seen only in relation to the other sex. And how small a part of a woman's life is that ...[5]

In film, a study of gender portrayals in 855 of the most financially successful U.S. films from 1950 to 2006 showed that there were, on average, two male characters for each female character, a ratio that remained stable over time. Female characters were portrayed as being involved in sex twice as often as male characters, and their proportion of scenes with explicit sexual content increased over time. Violence increased over time in male and female characters alike.[6]

According to a 2014 study by the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, in 120 films made worldwide from 2010 to 2013, only 31% of named characters were female, and 23% of the films had a female protagonist or co-protagonist. 7% of directors were women.[7] Another study looking at the 700 top‐grossing films from 2007 to 2014 found that only 30% of the speaking characters were female.[8] In a 2016 analysis of screenplays of 2,005 commercially successful films, Hanah Anderson and Matt Daniels found that in 82% of the films, men had two of the top three speaking roles, while a woman had the most dialogue in only 22% of films.[9]

Criteria and variants

The rules now known as the Bechdel test first appeared in 1985 in Alison Bechdel's comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For. In a strip titled "The Rule", two women, who resemble the future characters Mo and Ginger,[10] discuss seeing a film and one woman explains that she only goes to a movie if it satisfies the following requirements:

- The movie has to have at least two women in it,

- who talk to each other,

- about something other than a man.[11][12][13]

The other woman acknowledges that the idea is pretty strict, but good. Not finding any films that meet their requirements, they go home together.[10] The context of the strip referred to alienation of queer women in film and entertainment, where the only possible way for a queer woman to imagine any of the characters in any film may also be queer was if they satisfied the requirements of the test.[14]

The test has also been referred to as the "Bechdel–Wallace test"[15] (which Bechdel herself prefers),[16] the "Bechdel rule",[17] "Bechdel's law",[18] or the "Mo Movie Measure".[13] Bechdel credited the idea for the test to a friend and karate training partner, Liz Wallace, whose name appears in the marquee of the strip.[19][20] She later wrote that she was pretty certain that Wallace was inspired by Virginia Woolf's essay A Room of One's Own.[21]

Several variants of the test have been proposed—for example, that the two women must be named characters,[22] or that there must be at least a total of 60 seconds of conversation.[23] The test has also attracted academic interest from a computational analysis approach.[24] In June 2018, the term "Bechdel test" was added to the Oxford English Dictionary.[25]

According to Neda Ulaby, the test resonates because "it articulates something often missing in popular culture: not the number of women we see on screen, but the depth of their stories, and the range of their concerns."[19] Dean Spade and Craig Willse described the test as a "commentary on how media representations enforce harmful gender norms" by depicting women's relationships to men more than any other relationships, and women's lives as important only insofar as they relate to men.[26]

Use in film and television industry

Originally meant as "a little lesbian joke in an alternative feminist newspaper", according to Bechdel,[27] the test moved into mainstream criticism in the 2010s and has been described as "the standard by which feminist critics judge television, movies, books, and other media".[28] In 2013, Internet culture website The Daily Dot described it as "almost a household phrase, common shorthand to capture whether a film is woman-friendly".[29] The failure of major Hollywood productions to pass the test, such as Pacific Rim (2013), was addressed in-depth in the media.[30] In 2013, four Swedish cinemas and the Scandinavian cable television channel Viasat Film incorporated the Bechdel test into some of their ratings, a move supported by the Swedish Film Institute.[31]

In 2014, the European cinema fund Eurimages incorporated the Bechdel test into its submission mechanism as part of an effort to collect information about gender equality in its projects. It requires "a Bechdel analysis of the script to be supplied by the script readers".[32]

In 2018, screenwriting software developers began incorporating functions that allow writers to analyze their scripts for gender representation. Software with such functions includes Highland 2, WriterDuet and Final Draft 11.[33]

Application

In addition to films, the Bechdel test has been applied to other media such as video games[34][35][36] and comics.[37] In theater, British actor Beth Watson launched a "Bechdel Theatre" campaign in 2015 that aims to highlight test-passing plays.[38]

Pass and fail proportions

The website bechdeltest.com is a user-edited database of some 6,500 films classified by whether they pass the test, with the added requirement that the women must be named characters. As of April 2015[update], it listed 58% of these films as passing all three of the test's requirements, 10% as failing one, 22% as failing two, and 10% as failing all three.[39]

According to Mark Harris of Entertainment Weekly, if passing the test were mandatory, it would have jeopardized half of the 2009 Academy Award for Best Picture nominees.[22] The news website Vocativ, when subjecting the top-grossing films of 2013 to the Bechdel test, concluded that roughly half of them passed (although some dubiously) and the other half failed.[40]

Writer Charles Stross noted that about half of the films that do pass the test only do so because the women talk about marriage or babies.[41] Works that fail the test include some that are mainly about or aimed at women, or which do feature prominent female characters. The television series Sex and the City highlights its own failure to pass the test by having one of the four female main characters ask: "How does it happen that four such smart women have nothing to talk about but boyfriends? It's like seventh grade with bank accounts!"[19]

Financial aspects

Several analyses have indicated that passing the Bechdel test is associated with a film's financial success. Vocativ's authors found that the films from 2013 that passed the test earned a total of $4.22 billion in the United States, while those that failed earned $2.66 billion in total, leading them to conclude that a way for Hollywood to make more money might be to "put more women onscreen."[40] A 2014 study by FiveThirtyEight based on data from about 1,615 films released from 1990 to 2013 concluded that the median budget of films that passed the test was 35% lower than that of the others. It found that the films that passed the test had about a 37 percent higher return on investment (ROI) in the United States, and an equal ROI internationally, compared to films that did not pass the test.[42]

In 2018, the Creative Artists Agency and Shift7 analyzed revenue and budget data from the 350 top-grossing films of 2014 to 2017 in the United States. They concluded that female-led films financially outperformed other films, and that those that passed the Bechdel test (60% of the films studied) significantly outperformed the others. They noted that of films since 2012 which took in more than one billion dollars in revenue, all passed the test.[43][44]

Explanations

Explanations that have been offered as to why many films fail the Bechdel test include the relative lack of gender diversity among scriptwriters[19] and other movie professionals, also called the "celluloid ceiling": In 2012, one in six of the directors, writers, and producers behind the 100 most commercially successful movies in the United States was a woman.[30]

Writing in the American conservative magazine National Review in 2017, film critic Kyle Smith suggested that the reason for the Bechdel test results was that "Hollywood movies are about people on the extremes of society — cops, criminals, superheroes — [which] tend to be men". Such films, according to Smith, were more often created by men because "women's movie ideas" were mostly about relationships and "aren't commercial enough for Hollywood studios".[45] He considered the Bechdel test just as meaningless as a test asking whether a film contained cowboys.[45] Smith's article provoked vigorous criticism.[46] Alessandra Maldonado and Liz Bourke wrote that Smith was wrong to contend that female authors do not write books that generate "big movie ideas", citing J. K. Rowling, Margaret Atwood and Nnedi Okorafor among others as counter-examples.[47][48]

Limitations

The Bechdel test only indicates whether women are present in a work of fiction to a certain degree. A work may pass the test and still contain sexist content, and a work with prominent female characters may fail the test.[17] A work may fail the test for reasons unrelated to gender bias, such as because its setting works against the inclusion of women (e.g., Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose, set in a medieval monastery) or because it has few characters in general (e.g., Gravity, which has only two named characters).[49][18] What counts as a character or as a conversation is not defined. For example, the Sir Mix-a-Lot song "Baby Got Back" has been described as passing the Bechdel test, because it begins with a valley girl saying to another "oh my god, Becky, look at her butt".[50][51][52]

In an attempt at a quantitative analysis of works as to whether they pass the test, at least one researcher, Faith Lawrence, noted that the results depend on how rigorously the test is applied. For example, if a man is mentioned at any point in a conversation that also covers other topics, it is not clear whether this means that the conversation meets or fails the test. Another question is how one defines the start and end of a conversation.[15]

Criticism

In response to its increasing ubiquity in film criticism, the Bechdel test has been criticized for not taking into account the quality of the works it tests (bad films may pass it, and good ones fail), or as a "nefarious plot to make all movies conform to feminist dogma".[53] According to Andi Zeisler, this criticism indicates the problem that the test's utility "has been elevated way beyond the original intention. Where Bechdel and Wallace expressed it as simply a way to point out the rote, unthinkingly normative plotlines of mainstream film, these days passing it has somehow become synonymous with 'being feminist'. It was never meant to be a measure of feminism, but rather a cultural barometer." Zeisler noted that the false assumption that a work that passes the test is "feminist" might lead to creators "gaming the system" by adding just enough women characters and dialogue to pass the test,[53] while continuing to deny women substantial representation outside of formulaic plots. Similarly, the critic Alyssa Rosenberg expressed concern that the Bechdel test could become another "fig leaf" for the entertainment industry, who could just "slap a few lines of dialogue onto a hundred-and-forty-minute compilation of CGI explosions" to pass off the result as feminist.[54]

The Telegraph film critic Robbie Collin disapproved of the test as prizing "box-ticking and stat-hoarding over analysis and appreciation", and suggested that the underlying problem of the lack of well-drawn female characters in film ought to be a topic of discourse, rather than individual films failing or passing the Bechdel test.[55] FiveThirtyEight's writer Walt Hickey noted that the test does not measure whether any one film is a model of gender equality, and that passing it does not ensure the quality of writing, significance or depth of female roles—but, he wrote, "it's the best test on gender equity in film we have—and, perhaps more important ..., the only test we have data on".[42]

Nina Power wrote that the test raises the questions of whether fiction has a duty to represent women (rather than to pursue whatever the creator's own agenda might be) and to be "realistic" in the representation of women. She also wrote that it remained to be determined how often real life passes the Bechdel test, and what the influence of fiction on that might be.[41]

Derived tests

The Bechdel test has inspired others, notably feminist and antiracist critics and fans, to formulate criteria for evaluating works of fiction, in part because of the Bechdel test's limitations.[53] In interviews conducted by FiveThirtyEight, women in the film and television industry proposed many other tests that included more women, better stories, women behind the scenes, and more diversity.[56]

Tests about gender and fiction

The "Mako Mori test", formulated by Tumblr user "Chaila"[57] and named after the only significant female character of the 2013 film Pacific Rim, asks whether a female character has a narrative arc that is not about supporting a man's story.[53] Comic book writer Kelly Sue DeConnick proposed a "sexy lamp test": "If you can replace your female character with a sexy lamp and the story still basically works, maybe you need another draft."[58][59]

The "Sphinx test" by the Sphinx theater company of London asks about the interaction of women with other characters, as well as how prominently female characters feature in the action, how proactive or reactive they are, and whether they are portrayed stereotypically. It was conceived to "encourage theatremakers to think about how to write more and better roles for women", in reaction to research indicating that 37% of theater roles were written for women as of 2014[update].[60]

Johanson analysis, developed by film critic MaryAnn Johanson, provides a method to evaluate the representation of women and girls in movies. Although developed for the screen, it can also be applied to books and other media. It consists of adding or subtracting points based on different categories of representation. The analysis evaluates media on criteria that include the basic representation of women, female agency, power and authority, the male gaze, and issues of gender and sexuality. Johanson's 2015 study compiled statistics for every film released in 2015, and all those nominated for Oscars in 2014 or 2015. She also drew conclusions about movie profitability when women are represented well.[61][62][63]

Tests about characteristics other than gender

Sexuality

The "Vito Russo test" created by the LGBT organization GLAAD tests for the representation of LGBT characters in films. It asks: Does the film contain a character that is identifiably LGBT, and is not solely or predominantly defined by their sexual orientation or gender identity, as well as tied into the plot in such a way that their removal would have a significant effect?[64][65]

People of color

A test proposed by TV critic Eric Deggans asks whether a film that is not about race has at least two non-white characters in the main cast,[53] and similarly, writer Nikesh Shukla proposed a test about whether "two ethnic minorities talk to each other for more than five minutes about something other than race."[66][67] A 2017 speech by Riz Ahmed inspired the Riz test about the nature of Muslim representation in fiction,[68] and Johanson analysis includes a rating of films on their representation of women of color.[69]

The New York Times film critic Manohla Dargis suggested in January 2016 the "DuVernay test" (named for director Ava DuVernay), asking whether "African-Americans and other minorities have fully realized lives rather than serve as scenery in white stories."[70] It aims to point out the lack of people of color in Hollywood movies, through a measure of their importance to a particular movie or the lack of a gratuitous link to white actors.[71]

Nadia Latif and Leila Latif of The Guardian have suggested a series of five questions:

- Are there two named characters of color?

- Do they have dialogue?

- Are they not romantically involved with one another?

- Do they have any dialogue that isn't comforting or supporting a white character?

- Is one of them definitely not a magical negro?[72]

In 2018[73], culture critic, Clarkisha Kent, created a test "The Kent Test", a test similar to the Bechdel test aimed at women of color.[74] The test was released on the Equality for HER's websites and features 6 questions.

Tests about nonfiction

The Bechdel test has also inspired gender-related tests for nonfiction. Laurie Voss, CTO of npm, proposed a Bechdel test for software. Source code passes this test if it contains a function written by a woman developer which calls a function written by a different woman developer.[75] Press notice was attracted[76][77] after the U.S. government agency 18F analyzed their own software according to this metric.[78]

The Bechdel test also inspired the Finkbeiner test, a checklist to help journalists to avoid gender bias in articles about women in science,[79] and Danielle Kranjec's "Kranjec test" of including sources written by someone who is not male on any source sheet in Torah study.[80]

See also

- Damsel in distress

- Johanson analysis

- Manic Pixie Dream Girl

- Mary Sue

- Reverse harem

- Smurfette principle

- Tokenism

References

- ^ "Alison Bechdel Audio Name Pronunciation". TeachingBooks.net. Archived from the original on 2017-12-30. Retrieved 2017-12-30.

- ^ "Alison Bechdel Would Like You to Call It the "Bechdel–Wallace Test," ThankYouVeryMuch". 25 August 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-08-27. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ Raalte, Christa van (2015). "1. No Small-Talk in Paradise: Why Elysium Fails the Bechdel Test, and Why We Should Care". In Savigny, Heather; Thorsen, Einar; Jackson, Daniel; Alexander, Jenny (eds.). Media, Margins and Popular Culture. Springer. ISBN 9781137512819. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ "Bechdel-Test: Frauen spielen keine Rolle". Kurier. 8 August 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-08-15. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ^ Woolf, Virginia. Thomas, Stephen (ed.). "A Room of One's Own: Chapter 5". The University of Adelaide Library. University of Adelaide Press. Archived from the original on 2013-01-21. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- ^ Bleakley, A.; Jamieson, P. E.; Romer, D. (2012). "Trends of Sexual and Violent Content by Gender in Top-Grossing U.S. Films, 1950–2006". Journal of Adolescent Health. 51 (1): 73–79. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.02.006. PMID 22727080.

- ^ Sakoui, Anousha; Magnusson, Niklas (22 September 2014). "'Hunger Games' success masks stubborn gender gap in Hollywood". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2014. With reference to: Smith, Stacy L.; Pieper, Katherine. "Gender Bias Without Borders: An Investigation of Female Characters in Popular Films Across 11 Countries". See Jane. Archived from the original on 2016-04-12. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ Smith, Stacy L.; Choueiti, Marc; Pieper, Katherine; Gillig, Traci; Lee, Carmen; Dylan, DeLuca. "Inequality in 700 Popular Films: Examining Portrayals of Gender, Race, & LGBT Status from 2007 to 2014". USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. Archived from the original on 2015-08-08. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ^ Swanson, Ana (12 April 2016). "The problem with almost all movies". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2016-06-02. Retrieved 2016-04-16. With reference to: Anderson, Hanah; Daniels, Matt. "The Largest Analysis of Film Dialogue by Gender, Ever". Polygraph. Archived from the original on 2016-04-16. Retrieved 2016-04-16.

- ^ a b Martindale, Kathleen (1997). Un/Popular Culture: Lesbian Writing After the Sex Wars. Albany, NY: State Univ. of New York Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0791432891.

- ^ Bechdel, Allison. Dykes to Watch Out For. Firebrand Books (October 1, 1986). ISBN 978-0932379177

- ^ ""The Rule" comic page posted on Alison Bechdel's online photostream". Archived from the original on 2015-06-06. Retrieved 2015-05-06.

- ^ a b Alison Bechdel (August 16, 2005). "The Rule". DTWOF: The Blog. Archived from the original on 2018-09-17. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "The Bechdel Test Is And Always Has Been Queer". www.intomore.com. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- ^ a b Lawrence, Faith (June 2011). "SPARQLing Conversation: Automating The Bechdel–Wallace Test" (PDF). Paper presented at the Narrative and Hypertext Workshop, Hypertext 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-11-07. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ On the Fresh Air program on NPR on August 17, 2015, in response to a question from host Terry Gross, Bechdel said she would prefer the test be referred to as the Bechdel–Wallace Test.

- ^ a b Wilson, Sarah (28 June 2012). "Bechdel Rule still applies to portrayal of women in films". The Oklahoma Daily. Archived from the original on 2014-08-22. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- ^ a b Stross, Charles (28 July 2008). "Bechdel's Law". Charlie's Diary. Archived from the original on 2012-08-25. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d NPR Archived 2018-05-22 at the Wayback Machine Ulaby, Neda "The 'Bechdel Rule,' Defining Pop-Culture Character". September 2, 2008.

- ^ Friend, Tad (11 April 2011). "Funny Like a Guy: Anna Faris and Hollywood's woman problem". The New Yorker: 55. Archived from the original on 2014-07-01. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ^ Bechdel, Allison. "Testy". Alison Bechdel blog. Posted November 8, 2013 Archived 2015-04-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Harris, Mark (6 August 2010). "I Am Woman. Hear Me... Please!". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 2012-04-22. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "The Oscars and the Bechdel Test". Feminist Frequency. February 15, 2012. Archived from the original on 2013-11-07. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- ^ "Bechdel Test academic paper" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-06-21. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- ^ Suh, Haley (15 June 2018). "Words To Know By Now: Binge-Watching, Bechdel Test Added To Oxford English Dictionary". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2018-06-20. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ Spade, Dean; Willse, Craig (2016). Hawkesworth, Mary (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory. Oxford University Press. p. 556. ISBN 9780199328581.

- ^ Morlan, Kinsee (23 July 2014). "Comic-Con vs. the Bechdel Test". San Diego City Beat. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ Steiger, Kay (2011). "No Clean Slate: Unshakeable race and gender politics in The Walking Dead". In Lowder, James (ed.). Triumph of The Walking Dead. BenBella Books. p. 104. ISBN 9781936661138. Retrieved 2014-04-20.

- ^ Romano, Aja (18 August 2013). "The Mako Mori Test: 'Pacific Rim' inspires a Bechdel Test alternative". The Daily Dot. Archived from the original on 2015-04-28. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ a b McGuinness, Ross (18 July 2013). "The Bechdel test and why Hollywood is a man's, man's, man's world". Metro. Archived from the original on 2015-03-17. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "Swedish cinemas take aim at gender bias with Bechdel test rating". The Guardian. Associated Press. November 6, 2013. Archived from the original on 2014-03-28. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- ^ "Gender equality within Eurimages: current situation and scope for evolution". European Women's Audiovisual Network. Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ^ Ryzik, Melena (21 May 2018). "Is your script gender-balanced? The new test helping filmmakers get it right". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2018-06-20. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ Gray, Kishonna (2014). Race, Gender, and Deviance in Xbox Live: Theoretical Perspectives from the Virtual Margins. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 978-1317521808.

- ^ Anthropy, Anna (2012). Rise of the videogame zinesters: How freaks, normals, amateurs, artists, dreamers, dropouts, queers, housewives, and people like you are taking back an art form (Seven Stories Press 1st ed.). Seven Stories Press. ISBN 9781609803735. Retrieved 2014-04-20.

- ^ Agnello, Anthony John (July 2012). "Something other than a man: 15 games that pass the Bechdel Test". Gameological. Archived from the original on 2012-07-23. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Zalben, Alex (22 February 2012). "Witchblade/Red Sonja #1 Passes The Bechdel Test". MTV Geek!. Archived from the original on 2012-05-15. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Jo Caird (14 October 2015). "Does your show pass the Bechdel test? | Opinion". The Stage. Archived from the original on 2016-03-31. Retrieved 2016-02-05.

- ^ "Statistics". bechdeltest.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-29. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ a b Sharma, Versha; Sender, Hanna (2 January 2014). "Hollywood Movies With Strong Female Roles Make More Money". Vocativ. Archived from the original on 2014-03-07. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ a b Power, Nina (2009). One-dimensional woman. Zero Books. pp. 39 et seq. ISBN 978-1846942419. Retrieved 2014-04-20.

- ^ a b Hickey, Walt (1 April 2014). "The Dollar-And-Cents Case Against Hollywood's Exclusion of Women". FiveThirtyEight. Archived from the original on 2014-04-08. Retrieved 2014-04-08.

- ^ "Female-led films outperform at box office for 2014-2017". Shift7. Archived from the original on 2018-12-23. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ Desta, Yohana (11 December 2018). "Female-Led Movies Have Outperformed Male-Led Movies for the Last Three Years". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ a b Smith, Kyle (10 July 2017). "If You Like Art, Don't Take the Bechdel Test". National Review. Archived from the original on 2017-07-18. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ Gettell, Oliver (11 July 2017). "Conservative Film Critic Slammed for Bechdel Test Takedown". EW.com. Archived from the original on 2017-07-14. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ Maldonado, Alessandra (11 July 2017). ""National Review" mansplainer tries to take down Bechdel Test with "cowboy test"". Salon. Archived from the original on 2017-07-14. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ Bourke, Liz (18 July 2017). "Sleeps With Monsters: Stop Erasing Women's Presence in SFF". Tor.com. Archived from the original on 2017-07-18. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ Ellis, Samantha (20 August 2016). "Why the Bechdel test doesn't (always) work". The Guardian.

- ^ The Bechdel Test, and Other Media Representation Tests, Explained Archived 2018-04-18 at the Wayback Machine, by Nick Douglas, at Lifehacker; published October 10, 2017; retrieved April 17, 2018

- ^ This Bechdel Test Simulator Shows How Easy It Is to Predict Who Makes Sexist Movies (Men) Archived 2017-10-17 at the Wayback Machine, by Kara Brown, at Jezebel; published January 15, 2016; retrieved April 17, 2018

- ^ Gomez Maureira, M.A.; Rombout, L.E. (2015). "Sonifying Gender Representation in Film". In Chorianopoulos, Konstantinos (ed.). Entertainment Computing - ICEC 2015: 14th International Conference, ICEC 2015, Trondheim, Norway, September 29 - October 2, 2015, Proceedings. Springer. p. 546. ISBN 9783319245898.

- ^ a b c d e We Were Feminists Once: From Riot Grrrl to CoverGirl¨, the Buying and Selling of a Political Movement. PublicAffairs. 2016. pp. 55–57. ISBN 9781610395892.

- ^ Rosenberg, Alyssa (21 December 2018). "In 2019, it's time to move beyond the Bechdel test". The Washington Post. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Collin, Robbie (15 November 2013). "Bechdel test is damaging to the way we think about film". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2013-11-18. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ "Creating The Next Bechdel Test". FiveThirtyEight. Archived from the original on 2017-12-21. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Lena. "Pacific Rim Inspired the "Mako Mori Test." Uprising Gives the Character a Far Less Inspiring Arc". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on 2018-04-08. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Hudson, Laura (March 19, 2012). "Kelly Sue Deconnick on the Evolution of Carol Danvers to Captain Marvel [Interview]". Comics Alliance. Archived from the original on May 2, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ Helvie, Forrest (November 21, 2013). "The Bechdel Test and a Sexy Lamp". Sequart Organization. Archived from the original on 2015-04-24. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ Snow, Georgia (30 November 2015). "Theatre gets its own Bechdel Test". The Stage. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ Johanson, MaryAnn (2016-04-21). "Where Are the Women? rating criteria explained (updated!)". FlickFilosopher.com. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

- ^ Johanson, MaryAnn (May 11, 2016). "Where Are the Women?". Salt Lake City Weekly. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ Merin, Jennifer. "The Status of Feminist Film Criticism - A Roundup Report : Chaz's Journa| : Roger Ebert". rogerebert.com. Retrieved 2020-07-16.

- ^ "GLAAD introduces 'Studio Responsibility Index', report on LGBT images in films released by 'Big Six' studios". GLAAD. August 20, 2013. Archived from the original on 2015-03-17. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- ^ John, Arit (21 August 2013). "Beyond the Bechdel Test: Two (New) Ways of Looking at Movies". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2013-09-24. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ Shukla, Nikesh (18 October 2013). "After the Bechdel Test, I propose the Shukla Test for race in film". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 2016-11-22. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Dawn, Randee (17 November 2016). "Gender and race issues are slowly fading as more filmmakers consider three key tests". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2016-11-22. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Yusuf, Abeer; Berman, Sarah (2018-08-24). "Finally, There's a Bechdel Test for Muslim Representation". Vice. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- ^ Johanson, MaryAnn (2016-04-21). "Where Are the Women? rating criteria explained (updated!)". FlickFilosopher.com. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (29 January 2016). "Sundance Fights Tide With Films Like 'The Birth of a Nation'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2018-02-04. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ Evans, Dayna (February 1, 2016). "Could This Be the Bechdel Test for Race". The Cut. Archived from the original on 2018-02-04. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- ^ Latif, Nadia; Latif, Leila (January 18, 2016). "How to fix Hollywood's race problem". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2017-01-30. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- ^ "Introducing 'The Kent Test' for Female Characters of Color in the Stories We Tell". The Mary Sue. 2018-03-09. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ "Representation in Media". Equality for HER. 2018-06-01. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ Laurie Voss [@seldo] (27 Feb 2015). "Does your project pass the Bechdel test? To pass, a function written by a woman dev must call a function written by another woman dev" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Williams, Lauren C. (March 19, 2015), There's Now A Bechdel Test For The Tech World, ThinkProgress, archived from the original on 2015-03-24, retrieved 2015-03-24

- ^ Kolakowski, Nick (Mar 24, 2015), A Bechdel Test for Tech?, Dice.com, archived from the original on 2018-11-12, retrieved 2018-11-12

- ^ Elaine Kamlley; Melody Kramer (March 17, 2015). "Does 18F Pass the Bechdel Test for Tech?". Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

- ^ Brainard, Curtis (22 March 2013). "'The Finkbeiner Test' Seven rules to avoid gratuitous gender profiles of female scientists". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on 2013-04-04. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Hanau, Shira. "How a Bechdel test for Jewish texts is shaking up the beit midrash". Times of Israel. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

Further reading

- Julig, Carina Lousie (February 2, 2018). "The Lesbian Roots of the Bechdel Test". AfterEllen. Archived from the original on February 2, 2018.

External links

- Bechdel Test Movie List at bechdeltest.com (user-edited database)

- Bechdel Testing Comics blog at Tumblr (2011–2012)

- Bechdel Gamer blog (2012–2013)

- Women in Film, analysis tool for data from bechdeltest.com (Website defunct)