Arrau turtle

| Arrau turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Pleurodira |

| Family: | Podocnemididae |

| Genus: | Podocnemis |

| Species: | P. expansa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Podocnemis expansa (Schweigger, 1812)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Arrau turtle (Podocnemis expansa), also known as the South American river turtle, giant South American turtle, giant Amazon River turtle, Arrau sideneck turtle, Amazon River turtle or simply the Arrau,[1][3][4][5] is the largest of the side-neck turtles (Pleurodira) and the largest freshwater turtle in Latin America.[5] The species primarily feeds on plant material and typically nests in large groups on beaches.[5] Due to hunting of adults, collecting of their eggs, pollution, habitat loss, and dams, the Arrau turtle is seriously threatened.[5][6][7][8]

Range and habitat

[edit]Arrau turtles are found in the Amazon, Orinoco and Essequibo basins in Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela and Guyana.[4] On occasion, typically after floods, individuals turn up in Trinidad.[5] They are found in deep rivers, ponds, freshwater lagoons and flooded forest[5] in white-, black- and clear-water.[9]

Appearance

[edit]

Arrau turtles can reach up to 90 kg (200 lb) in weight and the carapace length is up to 1.07 m (3.5 ft).[10] Most individuals are considerably smaller with the average adult female having a carapace length of 64–71 cm (2.1–2.3 ft) and the average adult male 40–50 cm (1.3–1.6 ft).[5] In addition to an overall smaller size, males can be recognized by their longer tail and straighter carapace than the females.[10]

Arrau turtles are brown, gray or olive-green,[10] but the exact color varies depending on the algae growing on the carapace.[5]

Behavior

[edit]Feeding

[edit]Adult Arrau turtles feed almost entirely on plant material such as fruits, seeds, leaves, legumes and algae,[5][10] but may also take freshwater sponges, eggs and carcasses of dead animals (such as dead fish).[5] Captives have been recorded feeding on meat.[10][11] Juveniles feed on fish and plant material.[5] The species is mainly active during the day.[5]

Breeding and life cycle

[edit]

When nearing the breeding season, Arrau turtles migrate to certain sites where the eggs are laid.[10] In some locations, nesting occurs in large groups on beaches,[10] which reduces the risk posed by predators.[5] Some beaches have as many as 500 nesting females.[11] Mating occurs in the water.[11] During and just before the nesting season the species frequently basks, typically in groups. It is suspected that the additional heat accelerates the ovulation in the females.[12] At other times the species is generally not found on land.[12] When on land, it is usually very shy and retreats to the water at the slightest hint of danger.[5]

The female lays an average of 75–123 eggs (average varies depending on region),[8] which are placed during the night in a 60–80 cm (2.0–2.6 ft) deep nest that is dug on the beach.[5] The eggs are laid during the low water season and hatch as the water starts to rise. If it rises too fast or too early, the nest is flooded and the young die within the eggs.[8] As long as nests are not dug up by predators, the hatching success rate is usually high, averaging at 83%.[8]

The eggs hatch after about 50 days and the sex of the young depends on the nest temperature (females at higher temperatures, males at lower).[5][10] When hatching, the young are around 5 cm (2 in) long and dart directly for the water, but they emerge to the attentions of many predators so that only about five percent ever reach the adult feeding grounds.[13] When hatching, the females emit sounds which attract the young; they stay together for a period in the flooded forests.[14] Vocalizations appear to play an important role in the social life of this turtle and in addition to the "connect to newly hatched young" sound, four primary sounds have been documented during the nesting season: one used during migration, one before basking, one when nesting at night and finally one when in the water after nesting.[14]

They can reach an age of 20 years or more in the wild, and captives have lived for at least 25 years.[5] Based on certain scientific models it has been estimated that the largest individuals perhaps are as old as 80 years.[15]

Conservation status

[edit]

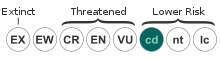

The Arrau turtle is widespread and was not considered threatened overall by the IUCN in 1996 (the year of the last full review),[1] but it has declined drastically,[12] and a draft review by the IUCN Species Survival Commission—Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group in 2011 recommended that it should be considered critically endangered.[4] The species is slow to mature; some have suggested that females reach maturity when 4–8 years old[5] and others have suggested about 17 years old.[15] Their social behavior, especially at certain nesting beaches, makes them and their eggs vulnerable to humans.[5] In addition to being used for food, they are sometimes used in traditional medicine.[9] At the main known nesting beaches, it is estimated that the number of nests fell from 34,000 in 1963 to 4,700 in 1981.[5] In the middle Orinoco River alone, it is estimated that as many as 330,000 nested in 1800, but less than half this number nested in 1945 and by the early 2000s (decade) it had fallen to 700–1300.[6] In addition to hunting and collecting of their eggs, threats include pollution, habitat loss,[5] and dams, which can cause flooding of nest sites.[8] Several countries in their range have implemented laws protecting the species, but hunting and egg collection (even if illegal) continues.[16][17] A number of conservation projects have been initiated. For example, 54 nesting beaches have been protected in Brazil,[5] beaches used by more than 1,000 females are protected in Colombia,[7] and since the mid-1990s many thousand eggs have been collected in Venezuela for safe incubation, the hatchlings "headstarted" (getting them through the most dangerous period) and then released.[6][16] All species in the genus Podocnemis are listed on CITES Appendix II.[4]

The slow growth limits its potential for major commercial turtle farming.[17] Nevertheless, about 880,000 turtles of various species were kept at 92 farms (both ones that are commercial and ones with conservation purpose) in 2004 in Brazil alone,[18] and some of these keep Arrau turtles, also in semi-intensive farm systems.[19]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group (1996). "Podocnemis expansa". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996. IUCN: e.T17822A97397263. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T17822A7500662.en.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Podocnemis expansa, The Reptile Database

- ^ a b c d Rhodin, Anders G.J.; Inverson, John B.; Roger, Bour; Fritz, Uwe; Georges, Arthur; Shaffer, H. Bradley; van Dijk, Peter Paul; et al. (Turtle Taxonomy Working Group) (3 August 2017). Rhodin A. G.J.; Iverson J.B.; van Dijk P.P.; Saumure R.A.; Buhlmann K.A.; Pritchard P.C.H.; Mittermeier R.A. (eds.). "Turtles of the world, 2017 update: Annotated checklist and atlas of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution, and conservation status(8th Ed.)" (PDF). Chelonian Research Monographs. Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation Project of the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group. 7 (8 ed.): 1–292. doi:10.3854/crm.7.checklist.atlas.v8.2017. ISBN 978-1-5323-5026-9. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Rivas, D. (2015). "Podocnemis expansa (Arrau Sideneck Turtle)" (PDF). The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Mogollones, S.C.; D.J. Rodriguez; O. Hernandez & G.R. Barreto (2010). "A Demographic Study of the Arrau Turtle (Podocnemis expansa) in the Middle Orinoco River, Venezuela". Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 9 (1): 79–89. doi:10.2744/CCB-0778.1. S2CID 86083211.

- ^ a b Overduin, M. (2 September 2015). "More Than 1,000 Turtles and Nests Protected in Colombia". Turtle Survival Alliance. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Vanzolini, P.E. (2003). "On clutch size and hatching success of the South American turtles Podocnemis expansa (Schweigger, 1812) and P. unifilis Troschel, 1848 (Testudines, Podocnemididae)" (PDF). Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 75 (4): 415–430. doi:10.1590/s0001-37652003000400002. PMID 14605677.

- ^ a b Alves, R.R.N. & G.G. Santana (2008). "Use and commercialization of Podocnemis expansa (Schweiger 1812) (Testudines: Podocnemididae) for medicinal purposes in two communities in North of Brazil". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 4 (3): 3. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-4-3. PMC 2254592. PMID 18208597.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Podocnemis expansa". INCT CENBAM, INPA. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Rivas, D. "Arrau turtle". Oregon Zoo. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Ferrara, C.R.; L. Schneider & R.C. Vogt (2010). "Podocnemis expansa (Giant South American River Turtle). Basking before the nesting season".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ The Simon and Schuster Encyclopedia of Animals

- ^ a b Ferrara, C.R.; R.C. Vogt; R.S. Sousa-Lima; B.M.R. Tardio & V.C.D. Bernardes (2014). "Sound Communication and Social Behavior in an Amazonian River Turtle (Podocnemis expansa)". Herpetologica. 70 (2): 149–156. doi:10.1655/HERPETOLOGICA-D-13-00050R2. S2CID 85899110.

- ^ a b Hernandez, O. & R. Espín (2006). "Efectos del reforzamiento sobre la población de Tortuga Arrau (Podocnemis expansa) en el Orinoco medio, Venezuela". Interciencia. 31: 424–430.

- ^ a b Peñaloza, C.L.; O. Hernandez & R. Espín (2015). "Head-starting the Giant Sideneck River Turtle (Podocnemis expansa): Turtles and People in the Middle Orinoco, Venezuela" (PDF). Herpetological Conservation and Biology. 10: 472–488.

- ^ a b Pantoja-Lima; Aride; de Oliveira; Félix-Silva; Pezzuti & Rebêlo (2014). "Chain of commercialization of Podocnemis spp. turtles (Testudines: Podocnemididae) in the Purus River, Amazon basin, Brazil: current status and perspectives". J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 10 (8): 8. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-10-8. PMC 3933064. PMID 24467796.

- ^ Sá; Quintanilha; Freneau; Luz; Borja & Silva (2004). "Crescimento ponderal de filhotes de tartaruga gigante da Amazônia (Podocnemis expansa) submetidos a tratamento com rações isocalóricas contendo diferentes níveis de proteína bruta". Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia. 33 (6): 2351–2358. doi:10.1590/S1516-35982004000900022.

- ^ Aguiar, J.C.; E.A. Adriano & P.D. Mathews (2017). "Morphology and molecular phylogeny of a new Myxidium species (Cnidaria: Myxosporea) infecting the farmed turtle Podocnemis expansa (Testudines: Podocnemididae) in the Brazilian Amazon". Parasitology International. 66 (1): 825–830. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2016.09.013. PMID 27693559.

External links

[edit]- Forero-Medina, G.; et al. (2019). "On the future of the giant South American river turtle Podocnemis expansa". Oryx. 55: 1–8. doi:10.1017/S0030605318001370.