Common box turtle

| Common box turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

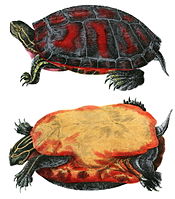

| Common box turtle, 1842 drawing | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | T. carolina

|

| Binomial name | |

| Terrapene carolina | |

| Subspecies | |

|

See text | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

The common box turtle (Terrapene carolina) is a species of box turtle with six existing subspecies. It is found throughout the eastern United States and Mexico. The box turtle has a distinctive hinged lowered shell (the box) that allows it to completely enclose itself. Its upper jaw is long and curved.

The turtle is primarily terrestrial and eats a wide variety of plants and animals. The females lay their eggs in the summer. Turtles in the northern part of their range hibernate over the winter.

Common box turtle numbers are declining because of habitat loss, roadkill, and capture for the pet trade. The species is classified as Vulnerable to threats to its survival by the IUCN Red List. Three U.S. states name subspecies of the common box turtle as their official reptile.

Classification

Terrapene carolina was first described by Linnaeus in 1758. It is the type species for the Terrapene genus and also has more subspecies than the other three species within that genus. The eastern box turtle subspecies was the one recognized by Linnaeus. The other five subspecies were first classified during the 19th century.[3] In addition, one extinct subspecies T. c. putnamii is distinguished.[4]

- Subspecies

| Country | Species | Scientific Name | Classified by | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Eastern box turtle | Terrapene carolina carolina | (Linnaeus) | 1758 |

| United States | Florida box turtle | Terrapene carolina bauri | Taylor | 1895 |

| United States | Gulf Coast box turtle | Terrapene carolina major | (Agassiz) | 1857 |

| United States | Three-toed box turtle | Terrapene carolina triunguis | (Agassiz) | 1857 |

| Mexico | Mexican box turtle | Terrapene carolina mexicana | (Gray) | 1849 |

| Mexico | Yucatán box turtle | Terrapene carolina yucatana | (Boulenger) | 1895 |

| North America | (no common name) | Terrapene carolina putnami | O.P. Hay | 1906 |

Parentheses around the name of an authority indicate that he originally described the subspecies in a genus other than Terrapene.

Description

The common box turtle (Terrapene carolina) gets its common name from the structure of its shell which consists of a high domed carapace (upper shell), and large, hinged plastron (lower shell) which allows the turtle to close the shell, sealing its vulnerable head and limbs safely within an impregnable box.[5] The carapace is brown, often adorned with a variable pattern of orange or yellow lines, spots, bars or blotches. The plastron is dark brown and may be uniformly coloured, or show darker blotches or smudges.[6]

The common box turtle has a small to moderately sized head and a distinctive hooked upper jaw.[6] The majority of adult male common box turtles have red irises, while those of the female are yellowish-brown. Males also differ from females by possessing shorter, stockier and more curved claws on their hind feet, and longer and thicker tails.[6]

There are six living subspecies of the common box turtle, each differing slightly in appearance, namely in the colour and patterning of the carapace, and the possession of either three or four toes on each hind foot. The subspecies Terrapene carolina triunguis is particularly distinctive as most males have a bright red head.[6]

Distribution

The common box turtle inhabits open woodlands, marshy meadows, floodplains, scrub forests and brushy grasslands[5][6] in much of the eastern United States, from Maine and Michigan to eastern Texas and south Florida. It is found in Canada in southern Ontario and in Mexico along the Gulf Coast and in the Yucatán Peninsula.[1][6] The species range is not continuous as the two Mexican subspecies, T. c. mexicana (Mexican box turtle) and T. c. yucatana (Yucatán box turtle), are separated from the US subspecies by a gap in western Texas. Three of the US subspecies; T. c. carolina (eastern box turtle), T. c. major (Gulf Coast box turtle) and T. c. bauri (Florida box turtle); occur roughly in the areas indicated by their names. T. c. triunguis (three-toed box turtle) is found in the central United States.[6]

Behavior

Common box turtles are predominantly terrestrial reptiles that are often seen early in the day, or after rain, when they emerge from the shelter of rotting leaves, logs, or a mammal burrow to forage. These turtles have an incredibly varied diet of animal and plant matter, including earthworms, slugs, insects, wild berries,[5] and sometimes even animal carrion.[6]

In the warmer summer months, common box turtles are more likely to be seen near the edges of swamps or marshlands,[5] possibly in an effort to stay cool. If common box turtles do become too hot, (when their body temperature rises to around 32°C), they smear saliva over their legs and head; as the saliva evaporates it leaves them comfortably cooler. Similarly, the turtle may urinate on its hind limbs to cool the body parts it is unable to cover with urine.[7]

Courtship in the common box turtle, which usually takes place in spring, begins with a "circling, biting and shoving" phase. These acts are carried out by the male on the female.[6] Following some pushing and shell-biting, the male grips the back of the female’s shell with his hind feet to enable him to lean back, slightly beyond the vertical, and mate with the female.[8] Remarkably, female common box turtles can store sperm for up to four years after mating,[6] and thus do not need to mate each year.[8]

In May, June or July, females normally lay a clutch of 1 to 11 eggs into a flask-shaped nest excavated in a patch of sandy or loamy soil. After 70 to 80 days of incubation, the eggs hatch, and the small hatchlings emerge from the nest in late summer. In the northern parts of its range, the common box turtle may enter hibernation in October or November. They burrow into loose soil, sand, vegetable matter, or mud at the bottom of streams and pools, or they may use a mammal burrow, and will remain in their chosen shelter until the cold winter has passed.[6] The Common box turtle has been known to attain the greatest lifespan of any vertebrate outside of the tortoises. One specimen lived to be at least 138 years of age.[9]

Human interaction

Conservation

Although the common box turtle has a wide range and was once considered common, many populations are in decline as a result of a number of diverse threats. Agricultural and urban development is destroying habitat, while human fire management is degrading it.[1] Development brings with it an additional threat in the form of increased infrastructure, as common box turtles are frequently killed on roads and highways. Collection for the international pet trade may also impact populations in some areas.[6][10] The life history characteristics of the common box turtle (long lifespan and slow reproductive rate)[6] make it particularly vulnerable to such threats. The common box turtle is therefore classified as a Vulnerable species on the IUCN Red List.[1] The common box turtle is also listed on Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), meaning that international trade in this species should be carefully monitored to ensure it is compatible with the species’ survival.[11] In addition, many U.S. states now regulate or prohibit the taking of this species.[6]

This species also occurs in a number of protected areas, some of which are large enough to protect populations from the threat of development, while it may also occur in the Sierra del Abra Tanchipa Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Conservation recommendations for the common box turtle include establishing management practices during urban developments that are sympathic to this species, as well as further research into its life history and the monitoring of populations.[1]

State reptiles

"The turtle watches undisturbed as countless generations of faster 'hares' run by to quick oblivion, and is thus a model of patience for mankind, and a symbol of our State’s unrelenting pursuit of great and lofty goals."

North Carolina Secretary of State[12]

Common box turtles are official state reptiles of four U.S. states. North Carolina and Tennessee honor the eastern box turtle,[13][14][15] Missouri names the three-toed box turtle,[16] and Kansas adopted the ornate box turtle in 1986.[1][17]

In Pennsylvania, the eastern box turtle made it through one house of the legislature, but failed to win final naming in 2009.[18] In Virginia, bills to honor the eastern box turtle failed in 1999 and then in 2009. For the most recent failure, a Republican legislator characterized the creature as being cowardly because of its shell. However, the main problem in Virginia was that the creature was too closely linked to neighbor state North Carolina.[19][20]

References

This article incorporates text from the ARKive fact-file "Common box turtle" under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License and the GFDL.

Citations

- ^ a b c d e Template:IUCN

- ^ Fritz Uwe; Peter Havaš (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World". Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 198. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ Fritz 2007, p. 196

- ^ Dodd, pp. 24–30

- ^ a b c d Capula, M. (1990). The Macdonald Encyclopedia of Amphibians and Reptiles. London: Macdonald and Co Ltd.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Ernst, C. H.; Altenbourgh, R. G. M.; Barbour, R. W. (1997). Turtles of the World. Netherlands: ETI Information Systems Ltd.

- ^ Alderton, D. (1988). Turtles and Tortoises of the World. London: Blandford Press.

- ^ a b Halliday, T.; Adler, K. (2002). The New Encyclopedia of Reptiles and Amphibians. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^ "Nature Serve". Retrieved March 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "CITES". CITES. Retrieved June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Eastern Box Turtle – North Carolina State Reptiles". North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ Shearer 1994, p. 321

- ^ "Official State Symbols of North Carolina". North Carolina State Library. State of North Carolina. Retrieved 26 January 2008.

- ^ "Tennessee Symbols And Honor" (PDF). Tennessee Blue Book: 526. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ "State Symbols of Missouri: State Reptile". Missouri Secretary of State Robin Carnihan. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- ^ "Ornate Box Turtle State Symbols USA". statesymbolsusa.org. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ "Regular Session 2009–2010: House Bill 621". Pennsylvania State Legislature. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ "SB 1504 Eastern Box Turtle; designating as official state reptile". Virginia State Legislature. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ Associated Press (20 February 2009). "Virginia House crushes box turtle's bid to be state reptile". NBC Washington. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

Bibliography

- Dodd Jr., C. Kenneth (2002). North American Box Turtles: A Natural History. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3501-4.

- Fritz, Uwe; Havaš, Peter (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World". Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 149–368. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- Shearer, Benjamin F.; Shearer, Barbara S. (1994). State names, seals, flags, and symbols (2nd ed.). Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-28862-3.

External links

- Common box turtle media from ARKive

- "Common box turtle" at the Encyclopedia of Life