Duchy of Anhalt

Duchy of Anhalt Herzogtum Anhalt | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1806–1918 | |||||||||||||

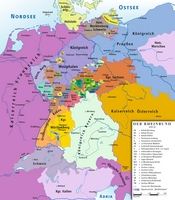

The 19th-century Duchy of Anhalt within the German Empire | |||||||||||||

Map of the Duchy of Anhalt (1863-1918) | |||||||||||||

| Status | Member of the Confederation of the Rhine Member of the German Confederation State of the North German Confederation State of the German Empire | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Dessau (when united) | ||||||||||||

| Government | Principality | ||||||||||||

| Duke | |||||||||||||

• 1901–1918 | Joachim Ernst | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||

| 1806 | |||||||||||||

• German Revolution | 1918 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

1: 13th century partition into Anhalt-Aschersleben, Anhalt-Bernburg and Anhalt-Zerbst. 2: 17th century partition into Anhalt-Bernburg, Anhalt-Dessau, Anhalt-Köthen, Anhalt-Plötzkau and Anhalt-Zerbst. 3: The three counties raised to duchies by Napoleon in 1806 were Anhalt-Bernburg, Anhalt-Dessau and Anhalt-Köthen. | |||||||||||||

The Duchy of Anhalt was a historical German duchy. The territory is now part of the federal state of Saxony-Anhalt.

History

Anhalt's origins lie in the Principality of Anhalt, a state of the Holy Roman Empire.

Dukes of Anhalt

During the 9th century, most of Anhalt was part of the duchy of Saxony. In the 12th century, it came under the rule of Albert the Bear, margrave of Brandenburg. Albert was descended from Albert, count of Ballenstedt, whose son Esico (died 1059 or 1060) appears to have been the first to bear the title of count of Anhalt. Esico's grandson, Otto the Rich, count of Ballenstedt, was the father of Albert the Bear, who united Anhalt with the Margraviate of Brandenburg (March of Brandenburg). When Albert died in 1170, his son Bernard, who received the title of duke of Saxony in 1180, became count of Anhalt. Bernard died in 1212, and Anhalt, separated from Saxony, passed to his son Henry I, who in 1218 took the title of prince and was the real founder of the house of Anhalt.

Princes of Anhalt

On Henry's death in 1252, his three sons divided the principality and founded the respective lines of Aschersleben, Bernburg and Zerbst. The family ruling in Aschersleben became extinct in 1315, and this district was subsequently incorporated with the neighbouring Bishopric of Halberstadt. The last prince of the line of Anhalt-Bernburg died in 1468 and his lands were inherited by the princes of the sole remaining line, that of Anhalt-Zerbst. The territory belonging to this branch of the family had been divided in 1396, and after the acquisition of Bernburg Prince George I made a further partition of Zerbst (Zerbst and Dessau). Early in the 16th century, however, owing to the death or abdication of several princes, the family had become narrowed down to the two branches of Anhalt-Köthen and Anhalt-Dessau (both issued from Anhalt-Dessau in 1471).

Wolfgang, who became prince of Anhalt-Köthen in 1508, was a staunch supporter of the Reformation, and after the Battle of Mühlberg in 1547 was placed under Imperial ban and deprived of his lands by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. After the peace of Passau in 1552, Prince Wolfgang bought back his principality, but as he was childless he surrendered it in 1562 to his kinsmen, the princes of Anhalt-Dessau. Ernest I (died 1516) left three sons, John V, George III, and Joachim I, who ruled their lands together for many years, and who, like Prince Wolfgang, favoured the reformed doctrines, which thus became dominant in Anhalt. Around 1546, the three brothers divided their principality and founded the lines of Zerbst, Plötzkau and Dessau. This division, however, was only temporary, as the acquisition of Köthen, and a series of deaths among the ruling princes, enabled Joachim Ernest, a son of John II, to unite the whole of Anhalt under his rule in 1570.

The first united principality of Anhalt was short-lived, and in 1603, it was split up into the mini-states of Anhalt-Dessau, Anhalt-Bernburg, Anhalt-Köthen, Anhalt-Zerbst and Anhalt-Plötzkau.

Joachim Ernest died in 1586 and his five sons ruled the land in common until 1603, when Anhalt was again divided, and the lines of Dessau, Bernburg, Plötzkau, Zerbst and Köthen were re-founded. The principality was ravaged during the Thirty Years' War, and in the earlier part of this struggle Christian I of Anhalt-Bernburg took an important part. In 1635, an arrangement was made by the various princes of Anhalt, which gave a certain authority to the eldest member of the family, who was thus able to represent the principality as a whole. This proceeding was probably due to the necessity of maintaining an appearance of unity in view of the disturbed state of European politics. In 1665, the branch of Anhalt-Köthen became extinct, and according to a family compact this district was inherited by Lebrecht of Anhalt-Plötzkau, who surrendered Plötzkau to Bernburg, and took the title of prince of Anhalt-Köthen. In the same year the princes of Anhalt decided that, if any branch of the family became extinct, its lands should be equally divided between the remaining branches. This arrangement was carried out after the death of Frederick Augustus, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst in 1793, and Zerbst was divided between the three remaining princes. During these years the policy of the different princes was marked, perhaps intentionally, by considerable uniformity. Once or twice, Calvinism was favoured by a prince, but in general the house was loyal to the doctrines of Martin Luther. The growth of Prussia provided Anhalt with a formidable neighbour, and the establishment and practice of primogeniture by all branches of the family prevented further divisions of the principality.

19th century duchies

In 1806, Napoleon elevated the remaining states of Anhalt-Bernburg, Anhalt-Dessau and Anhalt-Köthen to duchies. (Anhalt-Plötzkau and Anhalt-Zerbst had ceased to exist in the meantime.) These duchies were united in 1863 to form a united Anhalt again due to the extinction of the Köthen and Bernburg lines. The new duchy consisted of two large portions – Eastern and Western Anhalt, separated by the interposition of a part of the Prussian Province of Saxony – and of five enclaves surrounded by Prussian territory: Alsleben, Muhlingen, Dornburg, Goednitz and Tilkerode-Abberode. The eastern and larger portion of the duchy was enclosed by the Prussian government district of Potsdam (in the Prussian province of Brandenburg), and Magdeburg and Merseburg (belonging to the Prussian province of Saxony). The western or smaller portion (the so-called Upper Duchy or Ballenstedt) was also enclosed by the two latter districts and by the duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg.

The capital of Anhalt (at the times when it was a united state) was Dessau.

In 1918, Anhalt became a state within the Weimar Republic (see Free State of Anhalt). After World War II it was united with the Prussian parts of Saxony in order to form the new area of Saxony-Anhalt. Having been dissolved in 1952, the state was reestablished prior to the German reunification and is now part of the Bundesland Saxony-Anhalt in Germany.

Constitution

The duchy, by virtue of a fundamental law, proclaimed on September 17, 1859 and subsequently modified by various decrees, was a constitutional monarchy. The duke, who bore the title of "Highness," wielded the executive power while sharing the legislation with the estates. The diet (Landtag) was composed of thirty-six members, of whom two were appointed by the duke, eight were representatives of landowners paying the highest taxes, two of the highest assessed members of the commercial and manufacturing classes, fourteen of the other electors of the towns and ten of the rural districts. The representatives were chosen for six years by indirect vote and must have completed their twenty-fifth year. The duke governed through a minister of state, who was the praeses of all the departments—finance, home affairs, education, public worship and statistics.

Geography

In the west, the land is undulating and in the extreme southwest, where it forms part of the Harz range, mountainous, the Ramberg peak being the tallest at 1900 ft (579 m). From the Harz, the country gently slopes down to the Saale; between this river and the Elbe is fertile country. East of the Elbe, the land is mostly a flat sandy plain, with extensive pine forests, interspersed with bog-land and rich pastures. The Elbe is the chief river, intersecting the eastern portion of the former duchy, from east to west, and at Rosslau is met by the Mulde. The navigable Saale takes a northerly direction through the western portion of the eastern part of the territory and receives, on the right, the Fuhne and, on the left, the Wipper and the Bode.

The climate is generally mild, less so in the higher regions to the south-west. The area of the former duchy is 906 square miles (2,300 km2).[1] The population was 203,354 in 1871[2] and 328,007 in 1905.[1]

The country was divided into the districts of Dessau, Köthen, Zerbst, Bernburg and Ballenstedt with Bernburg being the most Ballenstedt the least populated. Four towns, namely Dessau, Bernburg, Cöthen and Zerbst, had populations exceeding 20,000. The inhabitants of the former duchy, who were primarily upper Saxons, belonged, with the exception of about 12,000 Roman Catholics and 1700 Jews, to the Evangelical Church. The supreme ecclesiastical authority was the consistory in Dessau; while a synod of 39 members, elected for six years, assembled at periods to deliberate on internal matters touching the organization of Church of Anhalt. The Roman Catholics were under the Bishop of Paderborn.

Rulers of Anhalt, Middle Ages

- Esico ?–1059/1060, first Count of Anhalt

- Otto the Rich, count of Ballenstedt

- Albert the Bear ?–1170

- Bernard ?–1212

- Henry I 1212–1252

Dukes of Anhalt, 1863–1918

- Leopold IV 1863–1871

- Friedrich I 1871–1904

- Friedrich II 1904–1918

- Eduard 1918

- Joachim Ernst 1918

Heads of the House of Anhalt since 1918

- Joachim Ernst 1918–1947

- Prince Friedrich 1947–1963

- Prince Eduard 1963–present

See also

References

Citations

Bibliography

- , Encyclopædia Britannica, 9th ed., Vol. II, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1878, p. 47.

- , Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed., Vol. II, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1911, pp. 44–46.

External links