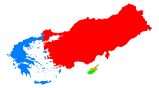

Embargo against Northern Cyprus

An international embargo against Northern Cyprus[1] is currently in place in several areas. The embargo is supported by the policy of the United Nations[2] and its application by the European Union is in line with a European Court of Justice (ECJ) decision taken in 1994.[3]

Northern Cyprus has been under severe embargoes since its unilateral declaration of independence in 1983,[4] and the embargoes are actively promoted by a Greek Cypriot campaign. Among the institutions that refuse to deal with the Turkish Cypriot community are the Universal Postal Union, the International Civil Aviation Organization and the International Air Transport Association. The economic embargo was greatly exacerbated upon the ruling of the ECJ in 1994, when the food certificates issued by Northern Cyprus were deemed unacceptable for the European Union.[5] Exports and flights from Northern Cyprus take place through Turkey, with direct flights being banned internationally. Turkish Cypriots face embargoes in the areas of sports and culture as well; Turkish Cypriot teams cannot play international matches, Turkish Cypriot athletes may not compete internationally unless they represent another country and some concerts by international musicians or bands in Northern Cyprus have been blocked.

Economic embargo

Development of the embargo

After the economic destruction of the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974, the southern part of the island received heavy subsidies from the international community to develop its economy. Northern Cyprus, meanwhile, only received aid from Turkey and very little international aid. This caused less economic development compared to the south and an economic dependence on Turkey.[6] The economic embargo prevents foreign cash flow as the external demand is stifled and the use of foreign savings through borrowing and capital inflows is rendered impossible.[4] The embargo has also restricted the tourism sector.[7]

Until 1994, the United Kingdom, Germany, and some other European Countries accepted Turkish Cypriot food products, including citrus, being directly imported. While a 1972 agreement granted access to the European market to goods regulated by the Republic of Cyprus, the agreement was interpreted as applying to the whole island and the Turkish Cypriot Chamber of Commerce gave certificates that bore the old stamps of Cyprus, rather than that of the Turkish Federated State of Cyprus or the TRNC. In 1983, upon the declaration of the TRNC, the Republic of Cyprus changed its stamps and notified the European Union and its member states that only certificates with its new stamps, originating from territory under the control of the Republic, should be accepted. However, the Council of Europe reiterated that both sides should benefit equally from such an agreement, and Turkish Cypriot goods continued to be imported directly.[3] The British Ministry of Agriculture issued a statement that "the Turkish-Cypriot certificates were just as good as the Greek-Cypriot ones."[8]

In 1992, a group of Greek Cypriot citrus producers sued the UK Ministry of Agriculture, and the case was referred to the European Court of Justice. The ECJ ruled against the acceptance of Turkish Cypriot goods, and thus in effect instituted an embargo against Northern Cyprus. The decision has been criticized as the ECJ stepping beyond its scope and precipitating an embargo that should only be imposed by political bodies.[3] The decision also exposed Turkish Cypriot goods to an additional duty of at least 14%, and cargoes were immediately turned back from European countries, resulting in profound damage in Turkish Cypriot economy.[8]

After the Annan plan

After the Annan Plan for Cyprus, there were promises by the European Union that sanctions on Northern Cyprus would be eased, including an opening of the ports, but these were blocked by the Republic of Cyprus. Turkish Cypriots can technically export to the world through the Green Line, but this requires the approval of the Republic of Cyprus and heavy bureaucracy, which is perceived as impractical by Turkish Cypriot business people.[9]

In the 2000s and 2010s, global enterprises and companies have opened up to Northern Cyprus through Turkey, which has been perceived as a form of normalization by Turkish Cypriots. However, Turkish Cypriots can access the global market only as consumers, but not as producers, and this access is still dependent on Turkey.[9]

Transport embargo

Northern Cyprus is accessible to international communications, postal services and transport only through Turkey.[10]

Flights to the Ercan International Airport of Northern Cyprus are banned internationally.[11] Non-stop flights only take place from Turkey, which is the only country to recognise Northern Cyprus, and all planes that fly to Northern Cyprus from other countries have to stop over in Turkey.[12] In 2005, a non-stop, chartered flight between Azerbaijan and Northern Cyprus, the first one ever from a country other than Turkey,[13] was hailed as a landmark and Azerbaijan started accepting Turkish Cypriot passports.[14]

In the congress of the Universal Postal Union in Rio de Janeiro in 1979, the Republic of Cyprus obtained a declaration that stated that Turkish Cypriot stamps were illegal and invalid.[6]

Turkish Cypriots have partly overcome restrictions on personal travel by obtaining passports issued by the Republic of Cyprus. According to Rebecca Bryant, a specialist on Cyprus, with the development of Turkish Airlines and the bankruptcy of Cyprus Airways, Ercan is busier than Larnaca International Airport as of 2015, but it is still dependent on Turkey.[9]

Cultural embargo

Sports

Turkish Cypriots cannot participate in international sports competitions.[15] The International Olympic Committee bans Turkish Cypriots from participating in the Olympic Games as independent athletes under the Olympic flag, and requires them to compete under the flag of a recognized country. Meliz Redif, the first Turkish Cypriot to participate in the Olympics, thus had to obtain Turkish citizenship, while some athletes refuse to compete for another country.[16]

Turkish Cypriot teams cannot play international matches.[17][18] In the first years after the Turkish invasion in 1974, Turkish Cypriot football teams were able to play international matches against teams from countries such as Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Libya. This was due to the tolerance shown by FIFA upon the initiative of its secretary, Helmut Kaiser. However, after the declaration of independence in 1983, Turkish Cypriot teams and the national team lost the ability to play international matches. A Turkish team, Fenerbahçe SK, had a camp in Northern Cyprus in 1990 and planned to play with a local team, but the match was not allowed by FIFA, who refused to accept the Cyprus Turkish Football Federation as a member. In the ELF Cup that took place in Northern Cyprus in 2006, FIFA successfully pressured the Afghan national team not to play in the tournament, and FIFA members Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan sent their futsal teams instead.[18] A Turkish Cypriot bid to join FIFA was rejected again in 2004, after the Annan Plan referendums.[13] In 2007, a friendly football match between Çetinkaya Türk S.K. and Luton Town F.C. was cancelled after Greek Cypriot pressure. In 2014, the Cyprus Turkish Football Federation applied to join the Cyprus Football Association, but the talks reached a deadlock.[17]

The sports isolation encountered by Northern Cyprus is not shared with all other unrecognized states, for example, Transnistria has a team that participates in international competitions. Northern Cyprus has participated in NF Board to ease the effect of international isolation in football.[13]

Music

The Republic of Cyprus deems business conducted in the north as illegal, which has hampered concerts by international bands or singers.[19] In 2010, a concert by Jennifer Lopez, scheduled to take place in Northern Cyprus, was cancelled after extensive campaigning by Greek Cypriot groups.[20] Rihanna also cancelled a concert after a similar campaign. In 2012, Julio Iglesias cancelled a concert and then sued the hotel and Turkish Cypriot authorities, claiming that he had been misled with regards to the legitimacy of the concert. Nevertheless, international concerts continue taking place.[19]

Northern Cyprus cannot participate or apply to participate in the Eurovision Song Contest.[15]

References

- ^ "EU to ease north Cyprus trade ban". BBC. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ "The thorn in Europe's side". The Economist. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ a b c Talmon, Stefan (2001). "The Cyprus Question before the European Court of Justice". European Journal of International Law. 12 (4): 727–750. doi:10.1093/ejil/12.4.727.

- ^ a b Günçavdi, Ömer; Küçük, Suat (2009). "Economic Growth Under Embargoes in North Cyprus: An Input‐Output Analysis". Turkish Studies. 10 (3): 365–392. doi:10.1080/14683840903141699.

- ^ Pegg, Scott (1998). International Society and the de Facto State. Ashgate Publishing. p. 117. ISBN 9781840144789.

- ^ a b Kyle, Keith. "The economic consequences of the 1974 conflict". Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ Gilmore, Audrey; Carson, David; Fawcett, Lyn; Ascenção, Mário (2007). "Sustainable marketing – the case of Northern Cyprus". The Marketing Review. 7 (2): 113–124. doi:10.1362/146934707x198830.

- ^ a b Pope, Hugh. "Sanctions ruling 'kills hope of united Cyprus': The Turkish-Cypriot leader, Rauf Denktash, condemns the European Court decision as harassment, reports Hugh Pope". The Independent. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ a b c Bryant, Rebecca. "The victory of Mustafa Akıncı in northern Cyprus gives hope to Turkish Cypriots of a better future". Greece at LSE. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "Cyprus settlement could open trade routes for Turkey". Al Monitor. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "Students Flock to Universities in Northern Cyprus". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ "Europe diary: Island isolation". BBC. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ a b c Isachenko, Daria (2012). The Making of Informal States: Statebuilding in Northern Cyprus and Transdniestria. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 164–5. ISBN 9780230392069.

- ^ "Landmark flight travels from Azerbaijan to North Cyprus without stopping in Turkey". The Daily Star. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ a b "Divided Cyprus begins to build bridges". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "Meliz Redif to make Olympic history". OBV. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ a b "Greek Cypriot footballer labelled traitor for joining Turkish Cypriot team". World Bulletin. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ a b Menary, Steve (2010). "Football and the Cyprus conflict". Soccer & Society. 11 (3): 253–260. doi:10.1080/14660971003619545.

- ^ a b Vatmanidis, Theo. "Lara Fabian's announcement of Northern Cyprus concert creates controversy". EuroVisionary. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "Jennifer Lopez cancels controversial concert in north Cyprus". NY Daily News. Associated Press. Retrieved 25 July 2015.