Franklin (automobile)

| |

| |

| Industry | Automotive |

|---|---|

| Genre | Sedans, touring cars, limousines, coupes, speedsters, taxis, light trucks |

| Founded | 1906 (1902, first car produced)[1] |

| Founder | Herbert H. Franklin (1866-1956)[2] |

| Defunct | 1934 |

| Fate | Bankruptcy |

| Headquarters | , |

Area served | United States |

Key people | John Wilkinson, chief engineer |

| Products | Automobiles Automotive parts |

| Owner | Herbert H. Franklin |

Number of employees | 3,210 in 1920 |

Franklin Automobile Company was a Syracuse, New York marketer of automobiles in the United States between 1906 and 1934. Controlled by Herbert H Franklin it had very few other significant shareholders. Franklin bought its vehicles from their manufacturer, H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company which was only moderately profitable and frequently missed dividends on common stock.

The two major characteristics of their automobiles were their air-cooled engines and in the early years their lightness and responsiveness when compared with other luxury cars.

The Franklin companies suffered financial collapse in April 1934. Aside from his consequent retirement CEO Herbert Franklin's lifestyle was unaffected.

History

Throughout its history, Franklin was a luxury brand and competed with other upscale automobiles of the day. As such, it fell victim to the Great Depression along with many luxury car manufacturers.[3] The company sold about 150,000 cars over the course of more than 30 years in existence.[4]

Herbert H. Franklin founded H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company in 1893 and, in 1901, teamed up with engineer John Wilkinson to develop an air-cooled engine. In 1902, the Franklin automobile was introduced. Because he was the primary investor, Franklin assumed control of the company, and named the auto manufacturing division Franklin Automobile Company. As president, he managed the company finances and business administration. Wilkinson was named chief engineer and granted control of the engineering and manufacturing operation.[2]

"In many years" H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company "earned only a modest profit and frequently failed to pay dividends on common stock".[6]

The Franklin motor car engine was invented by the engineer John Wilkinson and manufactured by the industrialist Herbert H. Franklin and marketed under his name.[3]

Franklin worked as a newspaper publisher, real estate agent and Columbia Bicycle shop owner in Coxsackie, New York. After he quit the publishing business in 1893, he relocated to Syracuse, New York.[7]

Die-cast manufacturer

Herbert Franklin became interested in die casting when an employee of a valve company he had helped to bring to Coxsackie was experimenting with a "hydrostatic moulding process", also known as die-casting.[7]

Franklin was presented with an opportunity to buy a patent for the process of die-casting and he jumped at the chance.[8] Later, he accurately predicted that "we are developing a process that will revolutionize the metal manufacturing business."[7]

By 1893 the money he earned from his many enterprises in Coxsackie supported him for almost a year and helped him launch the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company, which was the first machine die-casting enterprise in the world.[7] The company was incorporated on December 12, 1895.[9]

The die-casting business was split into a subsidiary called Franklin Die-Casting Corp. In 1926 H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company reabsorbed the die-casting subsidiary and, consequently, it also went under when the parent company failed.[9]

Wilkinson engine

John Wilkinson was born on February 11, 1868. He was a native of Syracuse and a member of one of the city's prominent families. His grandfather, John Wilkinson, Sr., was one of the original settlers in Syracuse.[10] As a young man, Wilkinson Sr. took inspiration from a poem about an ancient city and named the new village Syracuse. He was also an early city planner and laid out and named the village streets.[11]

Wilkinson was described as "rugged, good-natured, outgoing and athletic" and attended Cornell University, where he starred in baseball, track and football and managed to finish his coursework with honors. He earned a degree in mechanical engineering in 1889 and found a job with a local manufacturer of bicycles — then a mode of transportation very much in vogue. He went on to become a champion cyclist while developing a keen interest in the inner-workings of internal combustion engines and motor cars.[8]

Before he met Herbert Franklin, Wilkinson designed and built two prototype vehicles. In the summer of 1898 he tinkered with a one-cylinder air-cooled gasoline engine and by January 1, 1900, demonstrated his first automobile. Though Wilkinson's designs caught the attention of a group of New York businessmen, they failed to put Wilkinson's car into production.

One day while visiting the C. E. Lipe Machine Shop, where the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company die-casting business was located, a member of the group introduced Wilkinson to Herbert H. Franklin, who took a ride in Wilkinson's second prototype. Franklin was impressed and discussed the idea with Alexander T. Brown, one of the members of the New York Automobile Club. Between them it was agreed that Wilkinson should drop all previous experiments and start anew.[12] Brown and Franklin invested $1,100 so that Wilkinson could build a third prototype, which went on to become Franklin's first production model.[8]

Franklin automobiles

Wilkinson signed a formal contract with Franklin to go into business with him producing air-cooled automobiles on July 1, 1901.[12] Alexander T. Brown and Herbert H. Franklin combined efforts and created a startup they named "Brown and Franklin" to commence building and promotion of the Franklin automobile. The initial work of the business was financed equally by both men. "So great was Franklin's faith in the proposition, that he borrowed every cent of the money."[12]

The original staff consisted of six or seven people. "In one corner, with a drafting board in front of him, sat John Wilkinson and the bookkeeper, the stenographer and others were at desks and tables. Back in the original machine shop were two mechanics. These two men were building the first car. For two months they had worked shaping up this part and shaping up that, until the day came when they had a complete car." Later Brown and Franklin was absorbed by the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company.[12]

The company's first home was a four-story building at the northeast corner of West Fayette and South Geddes streets, leased from the Brown Lipe Gear Company.[9]

On November 1, 1901 the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company was restructured and the Franklin Automobile Company was spun off into a separate entity. Herbert Franklin named the business after himself and was the president and primary shareholder. He gave John Wilkinson stock and appointed him chief engineer. In the early days, Franklin ran the business side and Wilkinson made the engineering and manufacturing decisions. Alexander T. Brown and Willard C. Lipe were also important figures in the founding of the company and the original office was in the C. E. Lipe Machine Shop.[13]

From the outset, Wilkinson wanted to build a car that would be lightweight and economical. He believed that it should be the "acme of simplicity, so that the owner of a Franklin Car would have as little as possible to do with it mechanically." The first drawings of the vehicle contained the idea of a self starter which was to be operated by compressed air.[12]

By early December 1901, the local newspaper announced that the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company began operation of its automobile factory at West Fayette and South Geddes streets in the building owned by the Lipe estate. "The company will place gasoline carriages on the market in the spring. The factory includes a woodworking department in which all the bodies will be made."[14]

A total of four experimental machines were made before the company attempted to produce any for market.[15]

During 1902 Franklin sold a total of 13 cars priced at $1,100 each,[16] and from a modest beginning went on to become a successful car company. For 28 years, from 1902 to 1930, the company thrived and during much of that time enjoyed the distinction of being the city's largest employer.[8]

The First Franklin

The first Franklin took two months to build and was on the market by June 23, 1902. It holds the distinction of being the first four-cylinder automobile produced in the United States.[8] Most cars of the time had a single or two-cylinder motor.[17] As Franklin had hoped, the four-cylinder engine eliminated the bouncing suffered by cars manufactured with more common one-cylinder engines.[18]

The car weighed 900 pounds (410 kg) and traveled up to 12 miles per hour (19 km/h).[13] Its vertical four-cylinder air-cooled engine with overhead valves sat transversely at the front of a wooden chassis. The Franklin concept was copied by both Marion and Premier auto makers of Indianapolis, Indiana.[19]

The car was test driven on a short trip to Cortland, New York, and returned home by way of Skaneateles one afternoon.[20] S. G. Averell, a New York sportsman and relative of New York Governor W. Averell Harriman, bought the car on June 23, 1902. He paid $1,200. "It had a chain drive and the engine was mounted crosswise. The four-cylinder engine weighing 230 pounds (100 kg) was about one-fourth the weight of the car. The car had jump spark ignition, splash lubrication and enclosed planetary transmission. The gear ratio was 12-to-1 for low and 4-to-1 for high and there was reverse gear as well as the two forward. The steering gear was on the right, with wheel control."[9]

Light roadster

By September 1902 the 1,000 pounds (450 kg) Light Roadster was being advertised nationally in The Automobile Review. The engine was air-cooled, 7-horsepower with bore of cylinders 3.25-inch (83 mm) by 3.25-inch (83 mm) stroke. The ignition system was "jump spark coil with vibrator operated by dynamo and storage battery." The wheelbase was 66-inch (1,700 mm) with standard tread and 28-inch (710 mm) wheels.[15]

The vehicle's gasoline tank had a capacity of 7 gallons and its two forward speeds and reverse were complemented by two brakes — a double-acting band on the differential and a transmission brake.[15]

The bodies were made with individual or racing seats or with the ordinary single seat. Wooden wheels, designed by the company, could be "fitted."[15]

Franklin built a light tonneau that weighed about 1,250 pounds (570 kg). It had a longer wheelbase and the tonneau was detachable and could be converted into a "powerful touring car if desired."[15]

The company also built a heavier tonneau with a four-cylinder engine and a total weight of 2,500 pounds (1,100 kg). The size of the engines were 5-inch (130 mm) stroke and 5-inch (130 mm) bore.[15]

Franklin innovations

Franklin Automobile Company was a leader in innovation. Franklin cars were air-cooled,[3] which was considered simpler and more reliable than water cooling. The company's advertisements and brochures explained that air cooling did away with the "radiators, hoses, water pumps and headaches of 'normal' engine boiling and freezing."[8]

In July 1902, H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company introduced a constant level carburetor. It was originally designed to enable an engine to operate through great ranges of speed and throttle without a change in quality of the mixture to compensate for a problem with earlier carburetors where the speed of the engine was limited by the amount of gasoline as the engine drew differing amounts of air.[21]

Franklin cars were technological leaders, first with six-cylinders (by 1905) and later that year, the first eight-cylinder engine was built by Wilkinson in preparation for the "Vanderbilt Cup" race by placing two four-cylinder engines in tandem.[22] The automatic spark advance was introduced in 1907.[10] They were undisputed leaders in air-cooled cars at a time when virtually every other manufacturer had adopted water cooling as cheaper and easier to manufacture. Before the invention of antifreeze, the air-cooled car had a huge advantage in cold weather, and Franklins were popular among people such as doctors, who needed an all-weather machine.[16] The limitation of air-cooling was the size of the cylinder bore and the available area for the valves, which limited the power output of the earlier Franklins. By 1921, a change in cooling—moving the fan from sucking hot air to blowing cool air—led the way to the gradual increase in power.

The automobile was lightweight, a critical determinant in a well-performing car for that time, given the limited power of the engines available. Most Franklins were wood-framed, although the very first model in 1902 was constructed from an angle iron frame. Beginning in 1928, the heavier Franklin models adopted a conventional pressed-steel frame.[23]

Franklin's wooden frames, along with full-elliptic leaf springs, offered a "baby buggy" ride over the unpaved roads of the day. Wilkinson used a wooden frame constructed of three-ply laminated ash. The benefits were twofold: decreasing the weight of the vehicle and providing a better material to absorb shocks.[23]

Aluminum bodies were part of John Wilkinson's obsessive quest for the "scientific light weight" he strived for in all Franklin vehicles.[8] Lightweight aluminum was used in quantity, to the extent that Franklin was believed to be the largest user of aluminum in the world.[10] Franklin offered "scientific light weight and flexible construction at a time when other luxury car manufacturers were making ponderous machines."[3]

Through 1915, some Franklin models were capable of a top speed over 65 mph (105 km/h) and others could provide 32 miles per US gallon (7.4 L/100 km) under certain conditions. The last year of exposed valves in the engine, "with exposed points that were meant to be lubricated every day at noon, according to the car's manual",[10] was 1914. Subsequently valves were enclosed in individual dustproof chambers or "rocker boxes", lubricated by oil-soaked felt pads.

Change in oiling system

In 1912, Franklin introduced a change in their air-cooled motor when they began using a re-circulating type of oiling system on all but the 10-horsepower model. In this re-circulating system, "oil is carried in a sub-base bolted to the regular engine base and is forced by a gear driven pump through individual leads to each of the main bearings of the motor and to a sight feed on the dash.".[24] Designed by James Albert Smith, the design was known colloquially—and descriptively—as "Smith's urinal".

It was the intention of the designers of the Franklin motor that this oiling system not only reduce the possibility of smoking but add greatly to the economy of the motor, and the average consumption of oil in the new models was between 400 to 500 US gal (1,500 to 1,900 L; 330 to 420 imp gal). A convenience of this new type of oiling system was that the leads were placed outside of the engine base, where they were readily accessible in case of difficulty.[24]

Doman's list of firsts

Carl Doman was the Franklin Automobile Company chief engineer in the latter days of the company. In 1954 he cited a list of Franklin firsts:[12]

- First 4-cylinder engine (1902). Original model built in 1898.

- First in scientific light weight and flexible construction (1902).

- Fundamental features (1902), such as light unsprung weight, full elliptic springs and air-cooling appeared in first car marketed.

- First in valve-in-head cylinder (1902).

- First in throttle control (1902).

- First float-feed carburetor (1902).

- First 6-cylinder engine (1905). This engine was exhibited at the 1906 Auto Show in New York.

- First to employ drive through springs (1906).

- First to use transmission service brake (1906).

- First to adopt automatic spark advance (1907).

- First to use individual re-circulating pressure feed oiling system for engine (1912).

- First to use exhaust jacket for heating intake gases (1913).

- Pioneered closed bodies. First production sedan (1913).

- Pioneered aluminum pistons (1915).

- First to use an electric carburetor primer to facilitate cold weather starting (1917).

- First to use case-hardened crankshaft in regular production (1921).

- First to use centrifugal air-cleaner for carburetor (1922).

- First to use Duralumin connecting rods in regular production (1922).

- First to employ narrow steel front body pillar construction (1925).

Gallery of selected models

Main gallery of images: Commons:Category:Franklin vehicles

-

First Franklin produced, 1902. Owned by the Smithsonian

-

Franklin - 1902 Light Roadster

-

1907 Model D Roadster

-

1911 model with a group of salesmen - Syracuse Post-Standard, July 23, 1910

-

1912 race car Monterey Historic Automobile Races, taken in 2008

-

1918 model

-

1918 Model 9-B Touring

-

1919 Series 9 Roadster

-

1922 Model 9-B Sedan

-

1926 Franklin 11A Sedan

-

1927 Franklin Boattail Roadster

-

Franklin 1928

-

1929 model, photographed in Layton, New Jersey

-

1931 model, photographed in Seattle, Washington

Early production

Offerings for 1904 included a touring car model with a detachable rear tonneau and which seated 4 passengers. The transverse-mounted, vertical straight-four engine, producing 10 hp (7.5 kW), was mounted at the front of the car. A 2-speed planetary transmission was fitted. The car weighed 1,100 pounds (500 kg). List price was US$1300. By contrast, the Ford Model F in 1905 was priced at $2,000, the FAL was US$1750,[25] a Cole 30[25] or Colt Runabout was US$1500,[26] the Ford Model S $700, the high-volume Oldsmobile Runabout US$650,[27] Western's Gale Model A US$500,[28] the Black could be as low as $375,[29] and the Success hit the amazingly low US$250.[27]

The majority of Franklin auto parts were built in the Franklin plant which designed and manufactured the complete engine including the carburetor, bearings, connecting rod forgings, valve springs and pistons. Franklin also manufactured transmissions, front and rear axles, steering gears, stampings, bodies and instrument panels.[12]

Syracuse auto industry

In addition to the Franklin Automobile Company, there were several other motorized vehicle manufacturers in the Syracuse area during the early 1900s. These included, Brennan Motor Manufacturing Company, Century Motor Vehicle Company manufacturers of a steam powered model, H. A. Moyer Automobile Company who were originally carriage builders and later moved to manufacturers of "high-grade pleasure cars," Chase Motor Truck Company who were pioneers in the two-cycle, air-cooled commercial vehicle field, Palmer-Moore Company and the Sanford-Herbert Motor Truck Company who manufactured two lines of commercial vehicles.[17]

Early touring

On July 18, 1902, a few weeks after the cars debut, Willard C. Lipe, vice-president of the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company, gave one of the company's automobiles a little "endurance run" when he drove the car 57 miles (92 km) to Lisle, New York, returning the same day. He was accompanied by W. H. Brown. Total run for the day was 134 miles (216 km). On the return, they left Lisle at 2:00 pm and reached Onondaga Street in Syracuse at 7:30 pm. No effort was made to break speed records, but simply to demonstrate the reliable, steady going qualities of the vehicle which has the Wilkinson four-cylinder air-cooled motor. Although the afternoon was very hot, the motor took the hills without the slightest difficulty. Lipe believed that "some of the hills are probably as long, steep and rough as can be found in the State."[31]

John Wilkinson traveled to New York City in a Franklin 30-horsepower, six-cylinder Franklin on July 14, 1906. He reached the Hotel Manhattan in his automobile after a fast run from Syracuse. The trip took 15 hours and 15 minutes. He left Syracuse at 4:45 am and reached the hotel at 8:00 pm.[32]

According to Wilkinson "I had a splendid run. I averaged about 25 miles (40 km) an hour. The roads generally were smooth, but the run from Syracuse to Little Falls was a trifle rough. However, I made fairly good time between these points." Wilkinson had made this trip in a day on two former occasions including once with C. A Benjamin in a "little touring runabout."[32]

Franklin employees

The company grew from one small building with 65 employees in 1901, to 18 buildings with 3,200 workers by 1921.[12] Syracuse attracted mechanically minded workers, "many of whom matured to become famous for their innovative genius."[20]

In July 1931, a local newspaper reported that "As a result of Franklin working hard himself, he gets the utmost out of his men.".[33] At that time, Franklin Automobile Company was one of the oldest auto manufacturers in the country and for that reason, also the oldest employer of auto workers in the United States.[33] Statistics showed that there was a lower labor turnover than at any other automobile plant. This also applied to the executive staff, many of whom had been with Franklin since the company began business in 1902.[33]

The Associated Heads of Departments of the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company was an organization that "embraces within its membership the heads of departments of both factory and office." An outing was arranged for once a month during the summer, and the last one held "partook of the nature of a long tour, for which 17 cars were furnished by the company which carried the members of the association through some of the most picturesque and historic regions of Central New York.[34]

The "long line" of air-cooled cars left the auto works at 1:00pm and after posing for photographs in Clinton Square, left the city by the way of old Fayetteville toll road, through the hamlet of Orville and town of Manlius. The next stop was Cazenovia, some 900 feet (270 m) above level of Syracuse, where "a magnificent view" of Cazenovia Lake and the surrounding country can be seen. The group traveled through Chittenango Falls and Chittenango Springs before returning to Syracuse.[34]

Unique design

Franklins were often rather odd-looking cars, although some were distinctly handsome with Renault-style hoods. Starting in 1925, at the demand of dealers, Franklins were redesigned to look like conventional cars sporting a massive nickel-plated "dummy radiator" which served as an air intake and was called a "hoodfront." This design by J. Frank DeCausse enabled the Franklin to employ classic styling. The same year, Franklin introduced the boat-tail to car design.

The Franklin was a luxury car, even though it was less costly than Packard or Cadillac. Its most direct competitors included Buick, Hudson and the Jordan "L" car.[36]

Franklin's actual horsepower lagged with respect to its competition, but yet it moved over the road just about as fast. "Its road ability was exceptional. Franklin also had a reputation for being an easy and restful car to drive on long trips because of the very light spring on the foot throttle. This kept the right foot from getting tired."[36]

Automobile shows

The first automobile show was held in 1899, but according to H. H. Franklin; "One might say with truth that it was not an exposition at all, but simply, the assembling of manufactures to get going the automobile business of the season."[21]

A true exposition took place in January 1907, when the Automobile Show was held at the Madison Square Garden in New York. Franklin Auto Company was a participant.[37]

During the week of January 25, 1908, the Franklin Automobile Show was held at the Alhambra Hall in Syracuse. Each of the "out of town" accessory firms displayed products and had a representative in the city. The Franklin exhibit was prepared under the direction of George D. Babcock, of H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company. Machines used in the Franklin Laboratories and at Cornell University and Syracuse University for testing purposes were included in the exhibit. Among those were devices for determining the strength and life of metals, the resiliency and strength of wood and the durability of finished parts, valves and springs.[38]

The collection of 1908 models was more complete "than has ever before been attempted by the company, even for the New York or Chicago shows." Working models of automobiles made to scale showed hill climbing tests and various phases of engine efficiency. Every department of the factory was represented and showed the "processes of construction" they handled. The company displayed one of each type of engine Franklin ever made, including the first experimental model conceived by the firm.[38]

In January 1913, Franklin showed four machines in the National Automobile Show in Madison Square Garden in a special "air-cooling exhibit." There were four models on display that year, touring, roadster, coupe and sedan, all bodies were mounted on six-thirty chassis which were "exclusively made" for the exhibit.[39] The automobiles shown were the two big sixes of the Franklin line; a Model D five-passenger touring car and another of the same model, a four-passenger torpedo phaeton as well as two little sixes, including a Model M five-passenger touring car and a second Model M two-passenger, Victoria phaeton.[40]

A "striking" feature of the cars shown was the color of the Model D, torpedo phaeton. It was painted in the old coach design colors and was finished in a primrose yellow with shining black trimmings. The car was upholstered in a soft gray leather of a new finish for 1912 which, in contrast to the bright yellow of the car body, presented a "very striking appearance."[40]

The Model D touring car and the little six touring car were painted in regulation color, a Franklin blue with black body trimmings. The little six, Model M Victoria phaeton, which was a two-passenger runabout, had a Brewster green body with black running gear.[40]

The air-cooling exhibit planned for the show "will be one of the most novel ever attempted by the Franklin at an automobile show." It consisted of a six-cylinder motor mounted on a chassis, and the motor was seen running, getting its power from the motor generator of the Entz electric starter system, which was regular equipment on Franklin models. The sloping hood of the cooling chassis had glass sides and a glass top. Additionally, the dash and toe board of the chassis also were made out of glass. This permitted the spectators to obtain a full view of the engine as it was run under the power of the electric starter.[40]

The Franklin exhibit consisted of pleasure cars and the cooling chassis, as during the past year, they had discontinued manufacture of commercial cars.[40] Some of the Franklin employees who attended the January 1913, show were Herbert H. Franklin, president; John G. Barker; John Wilkinson, chief engineer; Author Holmes; M. H. Emond; Ralph Murphey and T. A. Young.[39]

During the January 1914, National Automobile Show in New York City, one of the models shown was a Franklin Sedan which was "designed especially for the man who likes to drive his own machine in all weathers and yet wants something larger than a coupe. The car was built for five-passengers.[41]

Test track

By the time May 1904, rolled around, residents of South Geddes Street in Syracuse between Delaware and West Onondaga streets were "aroused over the use of the Geddes Street hill by automobile drivers for testing purposes." The group filed a complaint to city authorities. They were preparing to take further action to insure the safety of those who had occasion to use the street daily for ordinary traffic.[42]

Residents measured the distance between Delaware and Onondaga streets and timed an automobile. They found the car was going more than 30 miles per hour (48 km/h). The highest speed was claimed to be attained as the machines approached the hill preparatory to ascent.[42]

The H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company had sent a letter in reply referring to the complaint made to Commissioner of Public Safety, R. S. Bowen, saying that it was a "necessity" for the company to use Geddes Street on which the company's plant was situated, for testing purposes. The purpose of the complaint by the residents was so that the city would enforce the speed ordinance.[42]

Court action

An action was brought against Herbert H. Franklin, Alexander T. Brown, John Wilkinson and the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company on February 28, 1905, by plaintiffs; Ernest I. White, Arthur R. Peck and Edward N. Trump and went to trial in Justice Scripture's Special Term of the New York Supreme Court.[43]

The plaintiffs sued for $50,000 damages on the ground that Franklin and Wilkinson, while in their employ, took "certain new ideas with regard to automobiles, models and drawings belonging to them and formed the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company giving them no returns for the money they had spent in developing the machines."[43]

The first witness called was Edward N. Trump, a mechanical and chemical engineer, who is general manager of the Solvay Process Company. He reported that Wilkinson was hired by the men composing the New York Automobile Company to develop an automobile. The machine that Wilkinson showed to him was cooled by air, instead of a water jacket. Up to that time he had never heard of an air-cooled automobile. The machine had four-cylinders and gasoline was the fuel used. Wilkinson afterward developed an improved machine, which was made for the New York Automobile Company at the plant of the Straight Line Engine Company.[43]

W. B. Crowley appeared for the plaintiffs, Giles Heath Stillwell, for H. H. Franklin and H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company. King, Waters & Page represented Alexander T. Brown and Theodore E. Hancock for John Wilkinson.[43]

Franklin automobile school

By June 29, 1909, a "repairman's course" was offered in the "automobile school" at the factory of the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company. Three members of the class constructed two Franklin cars from "raw stock" in two weeks. The work was "passed upon by the testers, just as cars in the regular course of manufacture are tested."[35]

The class had 26 members, under the supervision of I. O. Hoffman, formerly an instructor at Syracuse University. The course was 26 weeks long and provided both theory and practice, "most of the time being spent in practical work."[35]

Testing party

During June 1909, three of the newer models for the 1910 season were tested by company president, Herbert H. Franklin himself, with a specially organized party of factory heads. Franklin was personally driving one of the three cars and was subjected to a five-day tour in which they drove an average of 167 miles (269 km) per day, or a total of 823 miles (1,324 km). This was "over roads, through mountain climbs, and wherever hard going could be found in the general direction in which the party was traveling."[35]

The main course was from Syracuse to Boston, Massachusetts with an extensive detour through the Catskills. The largest car was the seven passenger 42-horsepower machine driven by Franklin. The other two cars were a 28-horsepower touring car carrying five passengers and driven by assistant engineer, Arthur Holmes, and a four-passenger car of 18 horsepower driven by engineer, R. A. Vail. The party also included vice-president, Giles H. Stillwell, secretary-treasurer, F. A. Barton, sales manager, F. R. Bump, advertising manager, J. E. Walker, sundry sales manager, J. G. Barker, traffic manager, Herbert Hess, superintendent, Frederick J. Haynes, chief engineer, John Wilkinson, engineer, R. W. Coughtry and Charles Slingerland.[35]

Race circuit

Franklin realized early on the value of auto racing as a public relations tool. Wilkinson had recent experience as a bicycle racer and put his knowledge to work promoting Franklin in races and endurance events. "The achievement took planning as well as doing. Gasoline had to be provided at prearranged pick-up places, for commercial supply spots were almost unknown over wide reaches. Indians and Chinese, among others seeing the cars on their hard route, expressed child-like wonder at seeing carriages without horses."[9]

- The first race was the Winton trip from San Francisco to New York on a $50 bet by Dr. Horatio Nelson Jackson, of Burlington, Vermont, and his driver, Sewell K. Crocker. They made it in 63 days.[9]

- John Wilkinson raced against Barney Oldfield in 1902, winning the state 5 miles (8.0 km) championship in the record time of 6:54:06.[22]

- In 1903, Franklin was a participant in the third annual hill climbing contest on the Eagle Rock Hill in West Orange, New Jersey, which was held by the Automobile Club of New Jersey on Thanksgiving Day. There were 36 entries in the competition. A 1,700 pound Franklin with 10-horsepower came in tenth place in event number two.[44]

- By 1904, a Franklin four-cylinder stock car set a record in a transcontinental run [45] in 32 days, 23 hours and 20 minutes. "The triumph of the light air-cooled engine car sent demand for Franklins zooming."[9]

- In 1905, Franklin was the first to market with a six-cylinder engine, which helped the car to halve its old coast to coast record the following year.[10]

- Demonstrating reliability, L. L. Whitman drove a Franklin from fire-ravaged, quake shattered San Francisco[9] to New York City in August 1906, in 15 days 2 hours 12 minutes, for the road distance of 4,100 miles (6,600 km) clocked and a new record.[46] Whitman was a well-known transcontinentalist who already held the San Francisco to New York City record of 33 days.[30] The trip began on August 2, 1906, at 6:00 pm. The men in charge were C. S. Carris, M. S. Bates, James Daley, C. B. Harris and S. L. Whitman and the car he was driving was a Franklin six-cylinder, a regular stock machine fitted up as a runabout."[30] In order that there would be no delay in case of a breakdown, Franklin had shipped all necessary parts of an automobile to cities along the route including; Reno, Omaha, Ogden, Utah and Cheyenne, Wyoming. These parts consisted of the axle, four wheels, and all of the necessary machinery to repair any part of the auto. "They will be held until the machine arrives there and in case they are not needed there will be shipped from Ogden to Cheyenne and from that city to Omaha. The men in charge of the auto do not intend to stop at all between San Francisco and New York except in case of an accident. They will sleep and eat on the machine and the auto will be kept in motion at all times."[47] "Carrying two teams of drivers, the big car went over 8,000 feet (2,400 m) grades, plowed through trackless desert, traveled 30 miles (48 km) on railroad ties, and suffered 66 hours of delay, not deducted from the total elapsed time for the transcontinental trek."[9]

- In 1907, a four-cylinder Franklin established a speed record from Chicago to New York when it made the trip in 39 hours and 53 minutes.[17]

- During June 1909, a 1910 Franklin won the one-gallon fuel economy contest held by the Buffalo Automobile Club. The car broke all economy contest records on a course that was 16.5 miles (26.6 km) in length with a roundtrip total a 33 miles (53 km) from the club headquarters in Williamsville, New York and "straight out Main Street" in Buffalo. The driver was S. G. Averell in a 1910 model G Franklin weighing a total of 2,498 pounds (1,133 kg) went 46.1 miles (74.2 km) on the allotted one gallon of gasoline. Averall broke the record held by himself with a 1909 Franklin Model G made in New York City two months previous. All the cars in the contest except the Franklin were water-cooled.[35]

- In 1911, a Franklin Model D placed second in the Desert Races trek from Los Angeles, California, to Phoenix, Arizona, driven by Ralph Hamlin. The car had an air-cooled 302 cubic-inch, six-cylinder, 38-horsepower engine mounted on a 123-inch (3,100 mm) wheelbase chassis.[23]

- One of the final tests of speed and durability took place in 1929 when E. G. "Cannonball" Baker driving a Franklin, raced and beat New York Central's crack 20th Century Limited passenger train on its run from New York to Chicago.[20]

Company officers

Giles H. Stilwell, head of the company legal department, was quoted in January 1904, at the annual banquet of the Automobile Club of Syracuse at the Yates Hotel as saying; "The lawyer looks at automobiling from the standpoint of how many suits he can get out of it. The sportsman asks how fast will it go? The manufacturer asks how much it will cost to make one and how many he can sell? The manufacturer has his troubles. The consumer complains and takes his troubles to the dealer, and the dealer shifts them back to the manufacturer. The manufacturer is all the time studying to improve the machine. It will not belong before the majority of the people who now use vehicles will own and operate automobiles, and good roads will follow and a recognition of the rights of automobilists."[48]

By January 29, 1912, an annual election of stockholders of the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company and the Franklin Automobile Company was held in Syracuse.[49]

|

|

|

Officers of the Franklin Automobile Company included;

- H. H. Franklin, president

- John Wilkinson, vice-president

- Frank A. Barton, secretary and treasurer

Directors were;

- H. H. Franklin

- John Wilkinson

- Frank A. Barton

- G. H. Stilwell

- E. H. Dunn

Commercial success

In 1911, the Franklin Commercial Division was located at 242 East Water Street in Syracuse.

By June, 1912 the State of California adopted Franklin cars for use by the highway commission. In the mining districts of Arizona and New Mexico, the Franklin was "practically the only car used by mining engineers."[17]

In the Philippines, Franklin cars had been in use for "years" by the superintendents and in New Zealand they were utilized by large business enterprises. A Franklin was also in use in the daily service, summer and winter, in the Yukon district of Alaska.[17]

World War I

During World War I, Wilkinson was selected to work with Cal Vincent of Packard in 1917 to design the Liberty V-12, a 450-horsepower aircraft engine. The engine was first designed as water-cooled and was later revamped at McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio to a V-12 air-cooled engine. "These first experiments were the basis for later air-cooled cylinder designs used during World War II and today in military as well as commercial aircraft."[12]

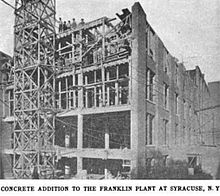

While Wilkinson was assisting with development of the V-12 engine, H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company concentrated on mass production of vital parts for Rolls Royce engines. The need for additional space in their factory was so dire, that Franklin added many additions to their plant during the war years. "Franklin's facilities for producing automobiles were most complete and modern as any in the industry."[12]

Public company

In February, 1920, the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company, which owned all of the capital stock of the Franklin Automobile Company, offered an "additional $1,000,000 of its seven percent, cumulative preferred sinking-fund stock at $100 a share and accrued dividends."[50]

The Franklin directors concluded that the fundamental features of the Franklin Car should be incorporated in a low price vehicle; one that would sell for $1,000. The directors made the decision to sell additional stock and with the monies generated, purchased acreage on Thompson Road just opposite the Oberdorfer Foundry. "A separate organization was set up in a building on South Salina Street to design, develop, and prepare for production of this new small car."[12]

The company stated that the production schedule for 1920 was over 16,000 cars, an increase of 80 percent over the 1919 production. A summary of profits for the previous five years showed the average yearly earnings equal to four times the dividend requirements on $3,500,000 preferred stock. Net sales at the end of December 1919, were $23,466,000 and net profits after depreciation were $1,841,000.[50]

Lower prices

By September 1920, (more than a year after the end of World War I), the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company joined with Ford Motor Company of Detroit, Michigan, in a movement to bring about a nationwide reduction in commodity prices to pre-war levels. The company announced a radical cut in the prices of Franklin autos which were lowered from 17 percent to 21 percent.[51]

H. H. Franklin, president of the company, in discussing the price-reduction decision with a reporter said that, "he agreed heartily with Mr. Ford that prices must come down, and that the sooner the business of the country gets back to normal, the better it will be for industry, commerce and all the people."[51] Franklin also promised that wages at the plant would not be affected by the lowering of prices and they would remain at "their present level."[51]

The Franklin Company "will at once go to the producers of materials used in the manufacture of Franklin cars and fight for a modification of existing contracts, such modifications to provide for price concessions corresponding with those made on Franklin motor car prices."[51]

Production was ramped up for a new, smaller model and engineer James L. Yarian was hired with reference from Wilkinson. On the production side, Joseph Baboock was chosen for his years of experience.[12]

Franklin Automobile Company engineer, Carl Doman wrote in 1954 about the results of the Franklin small car design;[12]

"Eventually the cars were assembled then road tested. Every one was enthusiastic The performance was very satisfactory and the riding quality outstanding. I well recall the car as I had decided to join the Small Car Division directly after graduating from the University of Michigan. Then as suddenly as the project was started, it was stopped. Why? No one seemed to have the answer However, as I look back on the situation through the eyes of a mature person rather than through the eyes of a twenty-two year old, I believe it was simply the lack of capital. Large production would have required high sums for working capital. In 1954 as I regretfully look back on the Small Car project I can see the turning in the road for Franklin. Had it been able to continue with this car I am convinced that "Franklin" would be another Ford, or another Chevrolet, or another Chrysler in sales volume and industrial strength."

Industrial complex

Franklin Automobile Company had a yearly payroll of $7,300,000 in April 1920. It was the largest industrial concern in the city of Syracuse.[1]

By 1921 when Wilkinson was honored on the 20th Anniversary of the Franklin Car, 70,000 had been shipped. The Franklin was sold in 525 cities in the United States and in 12 foreign countries. The company had grown from one small building with 65 employees in 1901, and by 1921 the Franklin plant covered 34.5 acres (140,000 m2), occupied 18 large buildings, and employed 3,200 workmen. A finished car rolled off the final assembly floor every 13 minutes.[12] The total floor space of the Franklin complex grew substantially over the years;[1]

- 1918 - 16.5 acres (67,000 m2)

- 1919 - 23.4 acres (95,000 m2)

- 1920 - 34.5 acres (140,000 m2) (planned and under construction)

The manufacturing plant was located at South Geddes and Marcellus Streets on the Near Westside,[13] current site of Fowler High School.[52] The facility was bounded by Geddes, Gifford, Magnolia and Marcellus streets.[18] Franklin was a major employer in Syracuse.[13]

Construction 1902

In August 1902, Robert J. Reidpath, architectural engineer, of Buffalo, New York, was hired to design the first Franklin manufacturing plant on South Geddes and Otisco streets. The contract was awarded to the firm of James E. Leamy & Company of Syracuse. There were 12 bids made for the work and the final bid was $40,000. The plans called for a five-story factory building, 53 feet (16 m) by 110 feet (34 m) with two boiler house 30 feet (9.1 m) by 50 feet (15 m) and a brick smokestack 150 feet (46 m) high. The building material was brick and the trimmings were stone.[53]

Leamy noted that "the lines for the buildings will be run tomorrow and the buildings will be commenced immediately." Final completion date was late December 1902. Architect, Gordon A. Wright, of Syracuse had general architectural supervision of the work. The building was equipped with an elevator and had a complete power system that was installed by Westinghouse Company. There was a 25,000 gallon water tank on the roof that was connected with the sprinkling system.[53]

Plans were in the works for two additional buildings. One was to be 40 feet (12 m) by 60 feet (18 m) and was to be located at the rear of the main factory. This building will be used for charging the motors with gasoline. The other structure was to be located at the left of the main building and was utilized as an office. "This will be a three-story building with all modern improvements. This building will be erected in the spring and in the meantime, the office will be located on the first floor of the factory."[54]

The factory was placed in operation before the present location in the Lipe shop was disturbed. The number of employees was increased to 300 during 1903 and increased to 350 by 1904. The factory was used jointly in the manufacture of both automobiles and die-castings.[54]

Construction 1904

A charging station was planned by May 29, 1904, in South Geddes Street. The contractor was William J. Burns and the architect was M. C. Conway. The building was constructed of brick and steel and was one-story high and 60 feet (18 m) by 130 feet (40 m). It was used as a "testing facility" for the automobiles.[55]

The second new building of the year was announced by July 1904, when Franklin announced an addition to the automobile factory in South Geddes Street. Robert J. Reidpath, architectural engineer, of Buffalo, New York, was hired once again to design the 66 feet (20 m) by 160 feet (49 m), five-story building. Including the equipment, the project cost $75,000. W. J. Burns was the contractor.[56]

In early August 1904, arrangements were made for construction of a large power plant in connection with the series of factory buildings in South Geddes Street. The architect was architectural engineer, Robert J. Reidpath of Buffalo and contractor was William J. Burns of Syracuse. The building was brick construction and sufficiently large to house engines and boilers with a capacity of 300-horsepower. All new equipment, including boilers, engines and generators were installed in the new building. The "present plant" which was inadequate to the company's needs was dismantled. It was proposed to have the building up and equipped and the new factory, known as letter "C" of the series, ready for occupancy before the end of 1904.[57]

There was a transfer of property on November 8, 1904, from Henry B. Gifford and others to Herbert H. Franklin of lot 6, block 3, farm lot 252, Gere map, Geddes for $1. Franklin then transferred the same property to the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company for $1.[58]

A petition was received by the city Common Council on October 24, 1904, from the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company asking permission for the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad Company to extend to the company's plant in South Geddes Street the spur track which was being extended to Kemp & Burpee Manufactuiong Company's plant. Following the petition, Alderman McGlade offered an ordinance granting the permission, which was unanimously adopted.[59] The railroad started work at once and extended the track additionally to Straight Line Engine Works and the Kemp & Burpee Manufacturing Company at the same time. It was necessary to place 1,000 feet (300 m) of track at a cost of no less than $25,000.[60]

Construction 1905

The H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company established a Gifford Street entrance to its plant at Geddes, Marcellus and Gifford streets by October 28, 1905. At this entrance a lodge was built for the "accommodation of the employees and others who have occasion to enter and leave the works by means of an automobile."[61]

The company bought two residences at 714 and 716 Gifford Street that were removed to make way for the new entrance. The building erected was 50 feet (15 m) by 80 feet (24 m), one-story high and of "artistic" frame construction. It contained a lounging room, a reading room and a writing room. "It will make a comfortable place for automobile owners to rest while their cars are being charged or repaired."[61]

Previously, the only entrance to the factory grounds, the repair shops and buildings was on Geddes Street. The company graded its Marcellus street property and built a high board fence "so the plant will present an attractive appearance."[61]

Construction 1906

The H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company awarded W. J. Burns the contract for building a reinforced concrete and brick building 65 feet (20 m) by 100 feet (30 m) and five-stories high to be used for general factory purposes. The company also was going to build a one-story shipping building just west of Harbor brook which will be served by branch tracks. The work will cost about $45,000.[62] The new building will connect with the group of buildings on the north wing. "With this additional space and equipment an increase in the production of at least 300 cars will be acquired."[63]

In September, 1906, the company announced plans to construct a fireproof freight house. Additionally, the company also built both a sawmill to be used in working up material used in the sills of the Franklin automobiles, and a narrow-gauge railway throughout the entire factory yards and buildings to facilitate the handling of materials. The freight house was constructed with wide platforms, which were completely covered by a protruding roof. A spur of the Lackawanna railroad was already complete, and tracks were laid that passed on each side of the building, one side for receiving goods and the other for dispatching them. The equipment of this department included, a shipper's office, accumulating room, crating room and sundry packing department.[63]

The construction and design of the sawmill building was similar to that of the freight house, but of different dimensions. The sawmill was 45 feet (14 m) by 68 feet (21 m) and 30 feet (9.1 m) high. It was situated in the lumber yard, parallel to the Lackawanna tracks, from which the lumber as received could be passed directly through."[63]

A plan for the beautifying of the grounds was also in operation. It called for grass plots, flower beds and climbing vines for the various buildings and many other features."[63]

Repair shop

By July, 1906, a new garage was established by the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company in connection with their factory repair shop. "Every comfort in the shape of waiting and reading rooms was provided to visitors."[64]

Construction 1912

The ground was first broken in 1912 for the first of two large buildings located on Gifford Street at a cost of $50,000. R. J. Reidpath, architect, of Buffalo, New York, prepared the plans. The building was 200 feet (61 m) by 150 feet (46 m) and had 30,000 square feet (2,800 m2) of floor space. The new structure adjoined the main factory building and was devoted chiefly to the production of sundry parts.[65]

A second building was planned for the following year, 1913, and was constructed next to the Gifford Street building. Both buildings were built of steel and brick and were considered modern and fireproof. They were built to accommodate a repair shop, blacksmith shop and the first chassis testing room.[49]

During this time, Franklin employed 1,300 men, however, some departments were working until 9:00 pm. Sales had grown 40 percent since 1911 and major growth and expansion was anticipated.[49]

Construction 1915

In June 1917, the company was using 6.5 acres (26,000 m2) of floor space for building cars at a rate of 3,500 per year. A comprehensive plan of expansion was adopted at that time and a large addition was begun.[66]

Construction 1916

During the period ending June 1916, four other additions were begun. The floor area of the company increased to more than 16 acres (65,000 m2), an increase of over 150 percent in one year.[66] By then, the company was producing 75 cars per day.[67]

Construction 1917

The month of March 1917, was the biggest in the history of Franklin Automobile Company. The company had recently added five new additions to relieve congestion and was able to produce 1,000 cars in the 233 "working hours" of the month. This was a rate of one car every 14 minutes, or 12,000 per year. According to a local newspaper; "Car production has gone ahead faster than floor area." The company had a 200 percent increase in orders since September 1916, and the books showed that demand was still ahead of supply.[66]

The firm had to secure extra space and leased the Crouse-Hinds Company building on Jefferson Street to use "for the making of tops and curtains for open cars and the assembling and testing of transmissions and for storage." Additionally, three-stories of the Heffron & Tanner Company's building in Richmond Avenue were used for storage of completed car bodies.[66]

The largest building recently constructed was used largely as an assembly plant. The first floor was occupied by stockrooms, final inspection of cars, the offices of the traffic department and shipping. Six covered railroad tracks facilitated the handling of all incoming and outgoing freight. Fifteen steel oil tanks were located underneath the shipping platforms, where they were protected from fire and were convenient for uploading the tank cars which were run on sidings. Six of the tanks were of 12,000 gallons capacity and held the entire contents of a tank car. Four of the tanks held 2,000 gallons, two held 1,000 gallons and three had a capacity of 3,000 gallons. Engine oil, fuel oil, paints and other oils used in the plant each had an individual tank from which were piped to the departments where they were used. The second floor of the building was devoted to chassis testing department. This was on the same level as Magnolia Street on the west side of the plant, "making it convenient to run out cars for road work."[66]

The third floor was used for final assembly, "the complete chassis coming down to the second floor for the bodies." The assembly, together with axle, sill, transmission and steering device assemblies and the storing of batteries occupied the fourth floor. The fifth floor was used for painting cars.[66]

Construction 1919

By 1919, the firm was set for another expansion after the stock it issued hiked from $2,000,000 to an authorization of $7,000,000.[67]

Construction of a new $500,000 addition to the plant and the opening of another large building as a body factory as well as the leasing of many thousand square feet of additional storage space were in the works by August, 1919.[68]

The expansion called for the "immediate" employment of 500 men with the possible addition of another 500. The Franklin Automobile Company issued a statement saying that "This tremendous expansion policy is the result of a determined effort to lift the production of Franklin cars to keep pace with the increasing demand and to a point where the yearly output will be 18,000 completed cars, or one car about every seven minutes of each working day."[68]

The ground was broken on August 2, 1919, for a new seven-story, re-enforced concrete manufacturing building. The other expansion changes included leasing a six-story manufacturing building near the Franklin works, "where work will begin immediately on the manufacture of enclosed bodies for Franklin cars."[68]

The company also closed a long term lease on the Edwards building in the wholesale section of the city which gave the factory 40,000 square feet (3,700 m2) additional floor space to be used for storage.[68]

When the changes and construction work were completed, the Franklin Company possessed 250,000 square feet (23,000 m2) of additional floor space. The new building, with a total of 160,000 square feet (15,000 m2), was located on the same site as the original auto works on the corner of Marcellus and Magnolia streets, adjoining the building occupied by the paint shop, assemblies and inspection departments. "A large expanse of glass on all sides will make it strictly a daylight plant."[68] By 1920, the company employed between 5,000 and 6,000 men in the city.[69]

Dealerships

A number of carload express shipments of automobiles were made in early December, 1906 by the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company to their San Francisco dealers, Boyer Motor Car Company. The returns on one of these shipments in the form of a C.O.D. (cash on delivery) were received by the United States Company, amounting to $15,000, which was paid in gold. This was the largest cash on delivery through the Syracuse office.[70]

Franklin was the first company to establish district sales managers in charge of separate territories.[20]

Ralph Hamlin became the distributor for Franklins in Southern California starting 1905. In the mid-1920s, he led a group of Franklin dealers "in revolt against the company, demanding a freshly redesigned and uncontroversial styled car to sell."[71]

During July 1909, the company opened six new branches around the country in addition to those already located in New York City, Chicago and Boston including San Francisco, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Buffalo, New York, Rochester, New York, Albany, New York and Syracuse.[35]

Herbert H. Franklin made his annual visit in July 1912, to the Franklin branches and agents. His itinerary included Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago, Salt Lake City, Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, Portland, Seattle, Spokane, Helena, St. Paul and Milwaukee.[65]

Wilkinson departs

In 1924, John Wilkinson left the company, allegedly though never verified, after a falling-out with Herbert Franklin over the insistence by Franklin that the new designs should "look more like other cars." The company had taken a lot of criticism in the popular press and from dealerships because of their unconventional front hood that didn't sport a radiator.[8] Franklin had recently hired J. Frank de Causse, a well-known car designer who had previously worked on the Rolls Royce and Locomobile. Wilkinson may have been alarmed when a new model, designed by de Causse, "wore a fake radiator-grille shell to make up for the fact that Franklin cars did not have a radiator. Wilkinson, who had always strived for light weight and form following function, could have felt that the faux grille not only looked out of place, but it also weighed more than the traditional one-piece aluminum hood grille that he had designed.[8] It is more likely, however, that Wilkinson left the company well before the deCausse car was designed for other reasons. Since the inception, all engineering was Wilkinson's responsibility, and all sales and business was HH Franklin's responsibility, and there was a tacit understanding that neither would interfere in the other's territory. But a series of small instances began to occur in the early 1920s which appeared to challenge Wilkinson's authority—the Model Z affair, the Stromberg carburetor—culminating with HHF's decision to change the appearance of the car. These were business decisions, for Wilkinson should have been well aware that he could not make advancements in engineering without money from the business, but it could have still been more than John Wilkinson was willing to bear.

After Wilkinson's departure, the designs of the vehicle dramatically changed over the next few years, the most visual of which was the front hood, which became more conventional in design. de Causse made many changes to the look of the car, "ever increasing their appeal"; however, he died around 1928, leaving Franklin without a designer.[23]

In 1928, Franklin hired Ray Dietrich to replace de Causse. During the next year, he created "some of the most exquisite designs that Franklin had ever produced." The designs attracted a new breed of buyers, however, the Great Depression soon took hold and production dropped.[23]

Economy and quality

H. H. Franklin, president of the company, was interviewed on January 22, 1928, and talked about the value of the Franklin car to the owner; "Franklin cars have always been economical in the consumption of gas and wear on tires, due to the scientific light weight that has been so carefully designed and built into them. Gasoline mileage alone does not satisfy the motorist, the car owner now desires to know about the cost of upkeep over a period of years, for he has come to realize that upkeep may become the most expensive part about his car."[72] Later that year, Franklin established a new cross-country record of 28.8 miles per US gallon (8.2 L/100 km; 34.6 mpg‑imp).[2]

Not only were Franklin cars touted as economical, but they had a well-earned reputation for quality. Many upgraded features were built into every vehicle such as casehardened crankshafts and high quality upholstery material and the loose, curled hair of the cushions. Additionally, "the unusual number of lace-web springs" that gives the cushions shape. According to H. H. Franklin, "it is those very things which insure long life that determine the true economy of motorcar operation."[72]

Garage and service station

In late 1909, the company leased the former Crosby Garage at Montgomery and Water streets which was used for repair purposes and the display of second-hand cars. The building had three floors "equipped with the most modern machinery" and electric power with a two-ton elevator.[35]

By 1930, the Ackerman Motor Car Company was a local Franklin distributor. For 23 years, John Connolly, secretary and treasurer, was associated with Franklin Automobile Company. In his new capacity, he was in charge of the service department of the company and under his guidance it was considered by "automotive men" to be one of the most efficiently operated in the country. The Franklin Service Station in Syracuse was thoroughly equipped and employed the most modern machinery and a corps of "factory trained mechanics." The company serviced fully 75 percent of the Franklin cars in the area and they carried a large stock of parts. They also had their own special machinery for such jobs as grinding valves, for searching out grounds and short circuits in the electrical system, and they were equipped for complete overhaul jobs as well as "to effect repairs of every nature." The company advertised that "a road car is available at all times for towing in cars which have been in accidents or have been otherwise disabled."[73]

Airplane engine

The first airplane-type motor ever to be employed in an automobile, one which had already flown in an airplane, appeared in the new line of Franklins that were introduced in 1930. The revolutionary step brought the air-cooled motor, which the Franklin Automobile Company developed "down to its most modern form as represented in aviation." The engine was 95 horsepower and operated in the range of 60 miles per hour (97 km/h) to 80 miles per hour (130 km/h) with a "smoothness of torque and power hitherto unparalleled in automotive power plants."[74]

The body design that year was "new in design and ultra-modern in conception to match the advance of the age symbolized by the air-cooled aviation motor." The new Franklin presented "a striking appearance, each model being distinctive and characterized by a new type of hood with gracefully arched front in which are mounted vertical vanes that give a slender effect to its proportions." It was noted that the same "pleasing contour" was also reflected in the body design which "are marked by a deep sectioned and well rounded roof." The entire style effect was set off by the staggered horizontal louvers, hood and belt moldings and the use of a military type visor.[74]

Two series of cars were included in the line; the Series 145 was mounted on a 125-inch (3,200 mm) chassis and the Series 147 was mounted on a 132-inch (3,400 mm) wheelbase.[74] Also shown in that year’s presentation were 16 standard body models including four "sports creations" such as the 1930 Speedster, the five-passenger Pirate touring, and the seven-passenger Pirate phaeton. All of these cars were in the standard line and were inspired by "recent Franklin models which met with favor among the world's leading custom car designers."[74]

Some new features were the concealed running boards, deep cut doors, horizontal dart louvers, original treatment of windows, moldings and paneling's, and the "rakish slant of the windshield." The Speedster and the two Pirate models were on 132-inch (3,400 mm) chassis and the Pursuit was on a 125-inch (3,200 mm) chassis.[74]

The new Franklin engine developed more power per cubic inch of cylinder capacity than the power plant of any other automobile, as well as developing greater power per pound of car weight than any other car in its class that year.[74]

Test engine in air

The ability of the Franklin air-cooled engine to get maximum power under all conditions was "conclusively proved" in a test at Dayton, Ohio where a standard Franklin automobile engine flew a Waco airplane throughout the day under extremely adverse weather conditions. During the test the weather was so cold that frost formed constantly on the intake manifold, even while the engine was warming up on the ground.[75]

Warning signs

Warning signs began to appear in 1927 that the company was headed into financial trouble. The firm's returns were sinking. From a record dividend in 1925 of $5.25 per common share, the company descended to a dividend of 92 cents the year before the stock market crash. In 1931, Franklin operations displayed a $1,000,000 loss.[67]

Lower prices again

By September 1931, Franklin Automobile Company announced new low prices on "current models" as low as $1,795 for the Transcontinent Sedan, with similar reductions on 21 other types comprising the complete De Luxe and Transcontinent lines.[76]

This action established the lowest sedan price in the company's 30 years of manufacture of air-cooled cars. It brought the base price under $2,000 for the first time and put Franklin in the position of the "lowest priced fine car on the market." The amount of reduction ranged as high as $500, representing 22 percent below previous list prices. Prices of De Luxe models after the reductions started at $2,395 for the sedan.[76]

It was emphasized that the reductions applied to even "the very latest production" which constitutes Series 15 Franklins incorporating the airplane-type air-cooled motor and the latest body features, along with all the mechanical refinements made "within recent months."[76]

The new scale of prices accomplished the aim the company initiated two years earlier, to introduce their established fine car standards at prices practically on a par with the medium price field. It was also announced at that time that a new national newspaper advertising and promotional effort was meeting with "excellent success."[76]

V12 engine design

In 1930 Franklin introduced a new type of engine which ultimately produced 100 horsepower (75 kW), with one of the highest power-to-weight ratios of the time. In 1932, in response to competition amongst luxury car makers, Franklin brought out a twelve-cylinder engine.[77] Air-cooled with 398 cubic inches (6.5 L) it developed 150 hp (110 kW). The V-12 was designed to be installed in a lightweight chassis, but the car became a 6,000-pound (2,700 kg) behemoth when Franklin engineers were overruled by management sent in from banks to recover bad loans. Although attractive, the Twelve did not have the ride and handling characteristics of its forebears. Unfortunately, this was simply the wrong vehicle to be building after the crash of 1929 and the Great Depression that followed. The cars sold poorly; only 200 were ever produced,[8] and came nowhere near to recouping the company's investment.

Bank management

Franklin's vice-president and general manager at the time of the fiasco, was new arrival, Edwin McEwen. He had initially been sent to Syracuse by a syndicate of seven banks. These banks had lent Franklin $5,000,000 in the late 1920s when Franklin was selling 7100-7500 cars a year. Herbert Franklin planned to increase plant capacity and develop new Franklin automobiles with the monies. The stock market crash on October 29, 1929, greatly reduced the number of automobiles that Franklin sold the following year and the company had problems repaying the bank loan.[8]

McEwen arrived in Syracuse to salvage what he could for the banks. Since H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company and its subsidiary, Franklin Automobile Company, were in dire financial trouble, something had to be done right away. The banks had given McEwen two conflicting missions, the first was to save Franklin as an automaker and the second was to wring as much cash as possible out of the company before it went under. It soon became clear to everyone involved, especially after McEwen began cleaning house that Franklin would not survive as a manufacturer of automobiles. McEwen's first act was to lay off and fire as many workers as he could. The end result was he gutted the engineering department and "pared the administrative staff to the bone."[8]

It was an uncomfortable working relationship, because although McEwen worked for the banks, he essentially ended up running Franklin and didn't necessarily make good business decisions. He canceled Franklin's long-standing contract with its principal body supplier, the Walker Body Company of Amesbury, Massachusetts, who soon went out of business, and Franklin then built their own bodies. McEwen hired a number of former Walker craftsmen and brought them to Syracuse.[8]

His personal goal seemed to turn to the V-12 program, although the reason is unclear. Possibly to prove to Franklin that he was in charge. Herbert Franklin had already made up his mind earlier in the year to produce a version of the Airman series using the new V-12 engine. In March 1932, two of the new models were exhibited in a New York auto show. About this time, McEwen, "dived into the V-12 program."[8]

He single-handedly made the decision that instead of producing an Airman clone, as originally decided by Franklin, he would design an entirely different kind of automobile. Through Briggs Manufacturing Company's, LeBaron subsidiary, McEwen acquired an all-new body design for the V-12. His decision to scrap the Airman heritage meant that nearly every component would be different than earlier specifications. The 12-cylinder car would now use a 144-inch (3,700 mm) wheelbase supplied by Parrish, as opposed to Airman's 132-flexible-steel frame.[8]

In the end, very little about the car was even produced by Franklin. It was an engineering nightmare of pieced together components. Franklin wasn't exactly thrilled with the new V-12. Here was H. H. Franklin, the boss, who had always run his own company, being told by a bank employee how to engineer and assemble the company's newest model.[8]

The car was fraught with problems. Rather than being stamped whole, like traditional Franklins, the body was made up of four or five separate stampings butt-welded together. Measurements were so inaccurate that bodies could be off dimensionally by more than an 1-inch (25 mm), side to side.[8]

The car was dubbed The Banker's Car, since McEwen was a bank employee. It weighed almost 6,000 pounds (2,700 kg), 1,800 pounds (820 kg) more than the Airman design proposed by Franklin.[8]

In November 1933, Edwin McEwen came down with pneumonia and died in January 1934. His two years at Franklin came to an end and he had done nothing useful to help the company survive and undoubtedly his actions helped lead to the eventual demise of the company.[8]

Business cycle

Franklin automobiles were revolutionary in their day. They were also one of the very first automobile manufacturers in the market.

As the 1900s drew to a close, Franklin had moved their product line to the middle and high end of the market. The company found themselves under increasing competition from the likes of Cadillac and Packard. Franklin was pressured to introduce a new and better car every year. A new Franklin with distinctive styling was introduced in 1911 to appeal to the markets.[21]

Herbert Franklin spoke about the early days in the industry at the Automobile Show in Madison Square Garden in 1906;

"When the American automobile was first placed in the market it was a badly constructed machine---a combination of ignorance of the art and fear that the American public would not pay for a good thing. Competition on the price basis threatened to lower even the low grade, or at least to keep it from rising. At this period, the leading American makers joined together under the standard of the Selden patent and stood together as solidly as competitors can for higher standards of making. The result has been better cars, more speed, power, reliability, and the public was quick to respond.[21]

During the 1910s, competition in the auto industry was ferocious, not only for Franklin, but for every auto maker in America who all saw increasing market erosion. Franklin found itself in competition with mass-produced autos in the lower price range. "Volume producers squeezed out smaller margins on an increasing number of autos."[45]

Franklin pared back, and by the mid-1910s, the company offered a single product line priced between $2,300 and $3,400. During early World War I, consumer prices escalated due to "exuberance by the buying public."[45] This was short-lived, however, and the country fell into a postwar recession, and buyer reluctance slowed new car sales.[45]

In December 1921, the company announced that its workforce of 3,000 employees would be working full-time by January 3, 1922. Factory officials were hoping to reach a daily output of 44 cars per day by February 1, 1922; however, it would take a few weeks to attain that goal "owing to time required to get all of the fabricated parts to the assemblies." For a number of weeks in late 1921, mostly on account of seasonal influences, the working week fluctuated from three days to five days.[78]

By 1925, the average price for an American car was $870, a huge drop which spelled impending doom for many car makers. Franklin failed largely because they produced higher-priced, hand-crafted, quality, low-volume automobiles when the public was smitten with low- to moderately priced, mass-produced automobiles.[45]

Franklin production over the years;[1]

- 1902 - 13 units - 6th in the nation[18]

- 1903 - 184 units[12]

- 1904 - 712 units[12]

- 1905 - 1,098 units - 5th in the nation[20]

- 1906 - 1,283 units - 9th in the nation[20]

- 1907 - 1,059 units - 7th in the nation[20]

- 1908 - 1,895 units - 8th in the nation[20]

- 1916 - 3,836 units

- 1919 - 9,177 units

- 1920 - 10,100 units

- 1921 - 8,545 units

- 1927 - 8,000 units

- 1929 - 14,000 units - Output was pushed up 5,000 above normal. The dealers handled the usual 9,000 and the extra 5,000 were stored in warehouses.

- 1930 - 6,043 units and Franklin reported an operating loss of $4,200,000.

- 1931 - 1,100 units[16]

- 1932 - 1,898 units

- 1933 - 1,330 units and had an operating loss of $819,000.[45]

Great Depression

When the company was first founded 30 years earlier, it was ranked among the largest auto makers in the United States; however, in the years that followed many other companies long since outstripped Franklin in volume. By the 1920s, production was running about 8,000 per year, soaring to a peak of 14,000 in 1929, although far below the numbers that other companies were achieving. Like other makers of high-priced cars, Franklin was badly hit by the Great Depression.[16]

In the early days of motor trade, air-cooled cars like Knox from Springfield, Massachusetts, Fox from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the Metz from Waltham, Massachusetts, Premier of Indianapolis, Indiana and the Frayer-Miller from Springfield, Ohio and Holmes, backed by Timken, from Canton, Ohio were common; however, by 1934, only Franklin had survived. "It survived not so much because of the winter proof feature as because of its quality." Founder Herbert Franklin prized his reputation for fine materials and scrupulous workmanship.[16]

H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company never shared in the spectacular profits of the early automobile industry. Franklin's peak in late years was attained in 1925 when a $2,000,000 profit was reported. In 1929, it earned only $1,100,000. During the years 1930 through 1934, the company reported deficits.[16]

The company declared bankruptcy on April 3, 1934, after reporting $2,088,000 in bank loans long overdue. For three years Franklin had "doggedly" fought off failure. He had "cajoled" his bankers into renewing bank loans that were equal to three times the company's current assets. Despite all hopes, reorganization plans fell through, and the company passed into bankruptcy and the hands of a receiver.[16]

In the end the city had a ghost plant in Geddes Street. It was used as inducement to bring Carrier Corporation to the city with 1,400 employees to offset the several thousand idled at Franklin. By odd coincidence, air-conditioning replaced air-cooling both in the plant and on the Thompson Road property owned by Franklin, which "H. H." had envisioned as a future industrial park for his business and its employees.[9]

Assets sold

Assets of the company were ultimately bought by Toledo, Ohio, entrepreneur Ward Canaday, who sold Franklin's real estate and plant machinery and invested the money into Willys-Overland Company.[8]

Carrier Corporation bought the Franklin plant for back taxes and manufactured air conditioners there for many years.[8]

Aircraft engines