Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

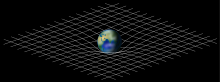

The Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) metric is an exact solution of Einstein's field equations of general relativity; it describes a homogeneous, isotropic, expanding (or otherwise, contracting) universe that is path-connected, but not necessarily simply connected.[1][2][3] The general form of the metric follows from the geometric properties of homogeneity and isotropy; Einstein's field equations are only needed to derive the scale factor of the universe as a function of time. Depending on geographical or historical preferences, the set of the four scientists — Alexander Friedmann, Georges Lemaître, Howard P. Robertson and Arthur Geoffrey Walker are customarily grouped as Friedmann or Friedmann–Robertson–Walker (FRW) or Robertson–Walker (RW) or Friedmann–Lemaître (FL). This model is sometimes called the Standard Model of modern cosmology,[4] although such a description is also associated with the further developed Lambda-CDM model. The FLRW model was developed independently by the named authors in the 1920s and 1930s.

General metric

The FLRW metric starts with the assumption of homogeneity and isotropy of space. It also assumes that the spatial component of the metric can be time-dependent. The generic metric which meets these conditions is

where ranges over a 3-dimensional space of uniform curvature, that is, elliptical space, Euclidean space, or hyperbolic space. It is normally written as a function of three spatial coordinates, but there are several conventions for doing so, detailed below. does not depend on t — all of the time dependence is in the function a(t), known as the "scale factor".

Reduced-circumference polar coordinates

In reduced-circumference polar coordinates the spatial metric has the form

k is a constant representing the curvature of the space. There are two common unit conventions:

- k may be taken to have units of length−2, in which case r has units of length and a(t) is unitless. k is then the Gaussian curvature of the space at the time when a(t) = 1. r is sometimes called the reduced circumference because it is equal to the measured circumference of a circle (at that value of r), centered at the origin, divided by 2π (like the r of Schwarzschild coordinates). Where appropriate, a(t) is often chosen to equal 1 in the present cosmological era, so that measures comoving distance.

- Alternatively, k may be taken to belong to the set {−1,0,+1} (for negative, zero, and positive curvature respectively). Then r is unitless and a(t) has units of length. When k = ±1, a(t) is the radius of curvature of the space, and may also be written R(t).

A disadvantage of reduced circumference coordinates is that they cover only half of the 3-sphere in the case of positive curvature—circumferences beyond that point begin to decrease, leading to degeneracy. (This is not a problem if space is elliptical, i.e. a 3-sphere with opposite points identified.)

Hyperspherical coordinates

In hyperspherical or curvature-normalized coordinates the coordinate r is proportional to radial distance; this gives

where is as before and

As before, there are two common unit conventions:

- k may be taken to have units of length−2, in which case r has units of length and a(t ) is unitless. k is then the Gaussian curvature of the space at the time when a(t ) = 1. Where appropriate, a(t ) is often chosen to equal 1 in the present cosmological era, so that measures comoving distance.

- Alternatively, as before, k may be taken to belong to the set {−1,0,+1} (for negative, zero, and positive curvature respectively). Then r is unitless and a(t ) has units of length. When k = ±1, a(t ) is the radius of curvature of the space, and may also be written R(t ). Note that, when k = +1, r is essentially a third angle along with θ and φ. The letter χ may be used instead of r.

Though it is usually defined piecewise as above, S is an analytic function of both k and r. It can also be written as a power series

or as

where sinc is the unnormalized sinc function and is one of the imaginary, zero or real square roots of k. These definitions are valid for all k.

Cartesian coordinates

When k = 0 one may write simply

This can be extended to k ≠ 0 by defining

- ,

- , and

- ,

where r is one of the radial coordinates defined above, but this is rare.

Curvature

Cartesian coordinates

In flat FLRW space using Cartesian coordinates, the surviving components of the Ricci tensor are[5]

and the Ricci scalar is

Spherical coordinates

In more general FLRW space using spherical coordinates (called "reduced-circumference polar coordinates" above), the surviving components of the Ricci tensor are[6]

and the Ricci scalar is

Solutions

| General relativity |

|---|

|

Einstein's field equations are not used in deriving the general form for the metric: it follows from the geometric properties of homogeneity and isotropy. However, determining the time evolution of does require Einstein's field equations together with a way of calculating the density, such as a cosmological equation of state.

This metric has an analytic solution to Einstein's field equations giving the Friedmann equations when the energy-momentum tensor is similarly assumed to be isotropic and homogeneous. The resulting equations are:[7]

These equations are the basis of the standard big bang cosmological model including the current ΛCDM model. Because the FLRW model assumes homogeneity, some popular accounts mistakenly assert that the big bang model cannot account for the observed lumpiness of the universe. In a strictly FLRW model, there are no clusters of galaxies, stars or people, since these are objects much denser than a typical part of the universe. Nonetheless, the FLRW model is used as a first approximation for the evolution of the real, lumpy universe because it is simple to calculate, and models which calculate the lumpiness in the universe are added onto the FLRW models as extensions. Most cosmologists agree that the observable universe is well approximated by an almost FLRW model, i.e., a model which follows the FLRW metric apart from primordial density fluctuations. As of 2003[update], the theoretical implications of the various extensions to the FLRW model appear to be well understood, and the goal is to make these consistent with observations from COBE and WMAP.

If the spacetime is multiply connected, then each event will be represented by more than one tuple of coordinates.[citation needed]

Interpretation

The pair of equations given above is equivalent to the following pair of equations

with , the spatial curvature index, serving as a constant of integration for the first equation.

The first equation can be derived also from thermodynamical considerations and is equivalent to the first law of thermodynamics, assuming the expansion of the universe is an adiabatic process (which is implicitly assumed in the derivation of the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric).

The second equation states that both the energy density and the pressure cause the expansion rate of the universe to decrease, i.e., both cause a deceleration in the expansion of the universe. This is a consequence of gravitation, with pressure playing a similar role to that of energy (or mass) density, according to the principles of general relativity. The cosmological constant, on the other hand, causes an acceleration in the expansion of the universe.

Cosmological constant

The cosmological constant term can be omitted if we make the following replacements

Therefore, the cosmological constant can be interpreted as arising from a form of energy which has negative pressure, equal in magnitude to its (positive) energy density:

Such form of energy—a generalization of the notion of a cosmological constant—is known as dark energy.

In fact, in order to get a term which causes an acceleration of the universe expansion, it is enough to have a scalar field which satisfies

Such a field is sometimes called quintessence.

Newtonian interpretation

This is due to McCrea and Milne [8] although sometimes incorrectly ascribed to Friedmann. The Friedmann equations are equivalent to this pair of equations:

The first equation says that the decrease in the mass contained in a fixed cube (whose side is momentarily a) is the amount which leaves through the sides due to the expansion of the universe plus the mass equivalent of the work done by pressure against the material being expelled. This is the conservation of mass-energy (first law of thermodynamics) contained within a part of the universe.

The second equation says that the kinetic energy (seen from the origin) of a particle of unit mass moving with the expansion plus its (negative) gravitational potential energy (relative to the mass contained in the sphere of matter closer to the origin) is equal to a constant related to the curvature of the universe. In other words, the energy (relative to the origin) of a co-moving particle in free-fall is conserved. General relativity merely adds a connection between the spatial curvature of the universe and the energy of such a particle: positive total energy implies negative curvature and negative total energy implies positive curvature.

The cosmological constant term is assumed to be treated as dark energy and thus merged into the density and pressure terms.

During the Planck epoch, one cannot neglect quantum effects. So they may cause a deviation from the Friedmann equations.

Name and history

The Soviet mathematician Alexander Friedmann first derived the main results of the FLRW model in 1922 and 1924. Although the prestigious physics journal Zeitschrift für Physik published his work, it remained relatively unnoticed by his contemporaries. Friedmann was in direct communication with Albert Einstein, who, on behalf of Zeitschrift für Physik, acted as the scientific referee of Friedmann's work. Eventually Einstein acknowledged the correctness of Friedmann's calculations, but failed to appreciate the physical significance of Friedmann's predictions.

Friedmann died in 1925. In 1927, Georges Lemaître, a Belgian priest, astronomer and periodic professor of physics at the Catholic University of Leuven, arrived independently at results similar to those of Friedmann and published them in the Annales de la Société Scientifique de Bruxelles (Annals of the Scientific Society of Brussels).[9] In the face of the observational evidence for the expansion of the universe obtained by Edwin Hubble in the late 1920s, Lemaître's results were noticed in particular by Arthur Eddington, and in 1930–31 Lemaître's paper was translated into English and published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Howard P. Robertson from the US and Arthur Geoffrey Walker from the UK explored the problem further during the 1930s. In 1935 Robertson and Walker rigorously proved that the FLRW metric is the only one on a spacetime that is spatially homogeneous and isotropic (as noted above, this is a geometric result and is not tied specifically to the equations of general relativity, which were always assumed by Friedmann and Lemaître).

This solution, often called the Robertson–Walker metric since they proved its generic properties, is different from the dynamical "Friedmann-Lemaître" models, which are specific solutions for a(t) which assume that the only contributions to stress-energy are cold matter ("dust"), radiation, and a cosmological constant.

Einstein's radius of the universe

Einstein's radius of the universe is the radius of curvature of space of Einstein's universe, a long-abandoned static model that was supposed to represent our universe in idealized form. Putting

in the Friedmann equation, the radius of curvature of space of this universe (Einstein's radius) is[citation needed]

,

where is the speed of light, is the Newtonian gravitational constant, and is the density of space of this universe. The numerical value of Einstein's radius is of the order of 1010 light years.

Evidence

By combining the observation data from some experiments such as WMAP and Planck with theoretical results of Ehlers–Geren–Sachs theorem and its generalization,[10] astrophysicists now agree that the universe is almost homogeneous and isotropic (when averaged over a very large scale) and thus nearly a FLRW spacetime.

Notes

- ^ For an early reference, see Robertson (1935); Robertson assumes multiple connectedness in the positive curvature case and says that "we are still free to restore" simple connectedness.

- ^ M. Lachieze-Rey; J.-P. Luminet (1995), "Cosmic Topology", Physics Reports, 254 (3): 135–214, arXiv:gr-qc/9605010, Bibcode:1995PhR...254..135L, doi:10.1016/0370-1573(94)00085-H

- ^ G. F. R. Ellis; H. van Elst (1999). "Cosmological models (Cargèse lectures 1998)". In Marc Lachièze-Rey (ed.). Theoretical and Observational Cosmology. NATO Science Series C. Vol. 541. pp. 1–116. arXiv:gr-qc/9812046. Bibcode:1999ASIC..541....1E. ISBN 978-0792359463.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ L. Bergström, A. Goobar (2006), Cosmology and Particle Astrophysics (2nd ed.), Sprint, p. 61, ISBN 3-540-32924-2

- ^ Wald, Robert. General Relativity. p. 97.

- ^ "Cosmology" (PDF). p. 23.

- ^ P. Ojeda and H. Rosu (2006), "Supersymmetry of FRW barotropic cosmologies", International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 45 (6): 1191–1196, arXiv:gr-qc/0510004, Bibcode:2006IJTP...45.1152R, doi:10.1007/s10773-006-9123-2

- ^ McCrea, W. H.; Milne, E. A. (1934). "Newtonian universes and the curvature of space". Quarterly Journal of Mathematics. 5: 73–80.

- ^ G. Lemaître (April 1927). "Un Univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extra-galactiques" (PDF). Annales de la Société Scientifique de Bruxelles (in French). 47: 49. Bibcode:1927ASSB...47...49L.

- ^ See pp. 351ff. in Hawking, Stephen W.; Ellis, George F. R. (1973), The large scale structure of space-time, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-09906-4. The original work is Ehlers, J., Geren, P., Sachs, R.K.: Isotropic solutions of Einstein-Liouville equations. J. Math. Phys. 9, 1344 (1968). For the generalization, see Stoeger, W. R.; Maartens, R; Ellis, George (2007), "Proving Almost-Homogeneity of the Universe: An Almost Ehlers-Geren-Sachs Theorem", Astrophys. J., 39: 1–5, Bibcode:1995ApJ...443....1S, doi:10.1086/175496.

References

- Friedmann, Alexander (1922), "Über die Krümmung des Raumes", Zeitschrift für Physik A, 10 (1): 377–386, Bibcode:1922ZPhy...10..377F, doi:10.1007/BF01332580

- Friedmann, Alexander (1924), "Über die Möglichkeit einer Welt mit konstanter negativer Krümmung des Raumes", Zeitschrift für Physik A, 21 (1): 326–332, Bibcode:1924ZPhy...21..326F, doi:10.1007/BF01328280 English trans. in 'General Relativity and Gravitation' 1999 vol.31, 31–

- Lemaître, Georges (1931), "Expansion of the universe, A homogeneous universe of constant mass and increasing radius accounting for the radial velocity of extra-galactic nebulæ", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 91: 483–490, Bibcode:1931MNRAS..91..483L, doi:10.1093/mnras/91.5.483

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) translated from Lemaître, Georges (1927), "Un univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extra-galactiques", Annales de la Société Scientifique de Bruxelles, A47: 49–56, Bibcode:1927ASSB...47...49L - Lemaître, Georges (1933), "l'Univers en expansion", Annales de la Société Scientifique de Bruxelles, A53: 51–85, Bibcode:1933ASSB...53...51L

- Robertson, H. P. (1935), "Kinematics and world structure", Astrophysical Journal, 82: 284–301, Bibcode:1935ApJ....82..284R, doi:10.1086/143681

- Robertson, H. P. (1936), "Kinematics and world structure II", Astrophysical Journal, 83: 187–201, Bibcode:1936ApJ....83..187R, doi:10.1086/143716

- Robertson, H. P. (1936), "Kinematics and world structure III", Astrophysical Journal, 83: 257–271, Bibcode:1936ApJ....83..257R, doi:10.1086/143726

- Walker, A. G. (1937), "On Milne's theory of world-structure", Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, Series 2, 42 (1): 90–127, Bibcode:1937PLMS...42...90W, doi:10.1112/plms/s2-42.1.90

- North J D:(1965)The Measure of the Universe - a history of modern cosmology, Oxford Univ. Press, Dover reprint 1990, ISBN 0-486-66517-8

- Harrison, E. R. (1967), "Classification of uniform cosmological models", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 137: 69–79, Bibcode:1967MNRAS.137...69H, doi:10.1093/mnras/137.1.69

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - d'Inverno, Ray (1992), Introducing Einstein's Relativity, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-859686-3. (See Chapter 23 for a particularly clear and concise introduction to the FLRW models.)