Greater Khorasan

Greater Khorasan or Ancient Khorasan (Persian: خراسان بزرگ or خراسان کهن) (also written Khurasan) is a historical region of Greater Iran mentioned in sources from Sassanid and Islamic eras which "frequently" had a denotation wider than current three provinces of Khorasan in Iran.[1] It also included parts of Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Pakistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikstan[1][2]

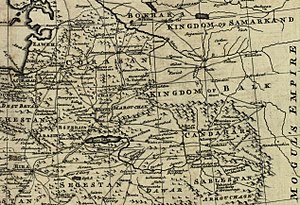

Khorasan in its proper sense comprised principally the cities of Balkh, Herat and Ghazni (now in Afghanistan), Nishapur and Tus (now in Iran), Merv (now in Turkmenistan), and Samarqand and Bukhara (now in Uzbekistan). However, the name has been used in the past to cover a larger region that encompassed most of Transoxiana and Soghdiana[3] in the north, extended westward to the Caspian Sea, southward to include the Sistan desert and eastward to the Hindu Kush mountains in Afghanistan.[4] Arab geographers even spoke of its extending to the boundaries of ancient India,[2] possibly as far as the Indus valley, in what is now Pakistan.[1] Sources from the 14th to the 16th century report that Kandahar, Ghazni and Kabulistan in Afghanistan formed the eastern part of Khorasan, overlapping with Hindustan.[5][6]

In the Islamic period, Persian Iraq and Khorasan were the two important territories. The boundary between these two was the region surrounding the cities of Gurgan and Damghan.[4] In particular, the Ghaznavids, Seljuqs and Timurids divided their empires into Iraqi and Khorasani regions. The adjective Greater is added these days to distinguish the historical region from the Khorasan province of Iran, which roughly encompasses the western half of the historical Khorasan.[7] It is also used to indicate that ancient Khorasan encompassed a loose collection of territories individually known by other popular names, such as Bactria, Khwarezmia, Sogdiana, Transoxiana, and Sistan or Arachosia.[citation needed]

Name

The name "Khorasan" is derived from Middle Persian khor (meaning "sun") and asan (or ayan literally meaning "to come" or "coming"), hence meaning "land where the sun rises".[8] The Persian word Khāvar-zamīn (Persian: خاور زمین), meaning "the eastern land", has also been used as an equivalent term.[4]

Geographical distribution

First established as a political entity by the Sassanids in the 3rd century AD,[9] the borders of the region have varied considerably during its 1600-year history. Initially the Khorasan province of Sassanid empire included the cities of Nishapur, Herat, Merv, Faryab, Taloqan, Balkh, Bukhara, Badghis, Abiward, Gharjistan, Tus or Susia, Sarakhs and Gurgan.[9]

It acquired its greatest extent under the Caliphs, for whom "Khorasan" was the name of one of the three political zones under their dominion (the other two being Eraq-e Arab "Arabic Iraq" and Eraq-e Ajam "Non-Arabic Iraq or Persian Iraq").[1] Under the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates, Khorasan was divided into four major sections and each section based on a single major city. The four principal cities were Nishapur, Merv, Herat and Balkh.[4]

In the Middle Ages, the term was loosely applied in Persia to all its territories that lay east and north east of Dasht-e Kavir and therefore were subjected to change as the size of empire changed. According to Ghulam Mohammad Ghobar, Afghanistan's current territories formed the major portion of Khorasan,[dubious ][10][11] as two of the four main capitals of Khorasan (Balkh, Merv, Nishapur and Herat) are now located in Afghanistan. Ghobar uses the terms Proper Khorasan and Improper Khorasan in his book to distinguish between the usage of Khorasan in its strict sense and its usage in a loose sense.[10] According to him, Proper Khorasan contained regions lying between Balkh in the east, Merv in the north, Sistan in the south, Nishapur in the west and Herat, known as the Pearl of Khorasan, in the center. Improper Khorasan's boundaries extended to Kabulistan and Hazarajat in the east, Sistan and Zabulistan in the south, Transoxiana and Khwarezm in the north, and Damghan and Gorgan in the west. It is mentioned in the Memoirs of Babur that:

The people of Hindustān call every country beyond their own Khorasān, in the same manner as the Arabs term all except Arabia, Ajem. On the road between Hindustān and Khorasān, there are two great marts: the one Kābul, the other Kandahār. Caravans, from Ferghāna, Tūrkestān, Samarkand, Balkh, Bokhāra, Hissār, and Badakhshān, all resort to Kābul; while those from Khorasān repair to Kandahār. This country lies between Hindustān and Khorasān.[6]

History

Before the region was conquered by Alexander the Great in 330 BC, it was part of the Achaemenid Empire and prior to that it was occupied by the Medes. The region that became known as Khorasan in geography of Eratosthenes was called Ariana at that time, which made up part of Greater Iran or the land where Zoroastrianism was the dominant religion. The southeastern region of Ariana fell to the Kushan Empire in the 1st century AD. The Kushan rulers introduced Buddhism in the Hindu Kush and nearby areas, in what is now Afghanistan. Numerous Buddhist temples and buried cities have been found in Afghanistan.[12][13] However, the region of Ariana (or Khorasan) remained predominantly Zoroastrian. One of the three great fire-temples of the Sassanids "Azar-burzin Mehr" is situated near sabzevar in Iran. The boundary of the region began changing until the Kushans and Sassanids merged together to form the Kushano-Sassanian civilization.

During the Sassanid era, the Persian Empire was divided into four quarters, Khvarvaran in the west, Bakhtar in the north, Nīmrūz in the south and Khorasan in the east next to Sind or Hind. Khorasan in the east saw some conflict with the Hephthalites who became the new rulers in the area but the borders remained stable. Being the eastern parts of the Sassanids and further away from Arabia, Khorasan quarter was conquered after the remaining Persia. The last Sassanid king of Persia, Yazdgerd III, moved the throne to Khorasan following the Arab invasion in the western parts of the empire. After the assassination of the king, Khorasan was conquered by Muslim troops in 647 AD. Like other provinces of Persia it became one of the provinces of Umayad dynasty.

The first movement against the Arab invasions was led by Abu Muslim Khorasani between 747 and 750. He helped the Abbasids come to power but was later killed by Al-Mansur, an Abbasid Caliph. The first independent kingdom from Arab rule was established in Khorasan by Tahir Phoshanji in 821, but it seems that it was more a matter of political and territorial gain. In fact Tahir had helped the Caliph subdue other nationalistic movements in other parts of Persia such as Maziar's movement in Tabaristan.

Other major independent dynasties in Khorasan were the Saffarids (861-1003,) Samanids (875-999), Ghaznavids (963-1167), Seljuqs (1037–1194), Khwarezmids (1077–1231), Ghurids (1149–1212), and Timurids (1370–1506). It should be mentioned that some of these dynasties were not Persian by ethnicity, nonetheless they were the advocates of Persian language and were praised by the poets as the kings of Iran.

Among them, the periods of the Ghaznavids of Ghazni and Timurids of Herat are considered as the most brilliant eras of Khorasan's history. During these periods, there was a great cultural awakening. Many famous Persian poets, scientists and scholars lived in this period. Numerous valuable works in Persian literature were written. Nishapur, Herat, Ghazni and Merv were the centers of all these cultural developments.

From the 16th century to the early 18th century, Khorasan was ruled by the Shia Safavid dynasty while the region to the east by the Sunni Khanate of Bukhara and the southeast by the Sunni Mughul Empire.[14] It was conquered in 1717, along with the rest of Persia, by the Ghilzai Afghans from Kandahar and became part of the Hotaki dynasty.[15][16] Following the assassination of Nader Shah Afshar in 1747, Khorasan was annexed with the Durrani Empire or modern-day Afghanistan.[17] In the early 19th century, much of Khorasan's western territory fell to the Qajar dynasty of Persia and remained as Iranian territory until modern day. Some of its northern areas were left under the Tsardom of Russia or later the Soviet Union.

Cultural importance

Khorasan has had a great cultural importance among other regions in Greater Iran. The literary New Persian language developed in Khorasan and Transoxiana and gradually supplanted the Parthian language.[18] The New Persian literature arose and flourished in Khorasan and Transoxiana[19] where the early Iranian dynasties such as Tahirids, Samanids and Ghaznavids were based.The early Persian poets such as Rudaki, Shahid Balkhi, Abu al-Abbas Marwazi, Abu Hafas Sughdi, and others were from Khorasan. Moreover, Ferdowsi, the author of Shahnameh, the national epic of Greater Iran, and Rumi, the famous Sufi poet, were also from Khorasan.

Until the devastating Mongol invasion of the thirteenth century, Khorasan remained the cultural capital of Persia.[20] It has produced scientists such as Avicenna, Al-Farabi, Al-Biruni, Omar Khayyám, Al-Khwarizmi, Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi (known as Albumasar or Albuxar in the west), Alfraganus, Abu Wafa, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī, and many others who are widely well-known for their significant contributions in various domains such as mathematics, astronomy, medicine, physics, geography, and geology.

In Islamic theology, jurisprudence and philosophy, and in Hadith collection, many of the greatest Islamic scholars came from Khorasan, namely Ahmad ibn Hanbal, Abu Hanifa, Imam Bukhari, Imam Muslim, Abu Dawood, Al-Tirmidhi, Al-Nasa'i, Al-Ghazali, Al-Juwayni, Abu Mansur Maturidi, Fakhruddin al-Razi, and others. Shaykh Tusi, a Shi'a scholar and Al-Zamakhshari, the famous Mutazilite scholar, also lived in Khorasan.

Demographics

| History of Afghanistan |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

Khorasan was originally inhabited by the ancient Indo-Iranians who migrated from the north to the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex in around 2000 BC. The BMAC was a Bronze Age culture situated in the upper Amu Darya region of Khorasan. Airyanem Vaejah (Land of Aryans), which is mentioned in the Zoroastrian Avesta, is also believed by some scholars to be situated in the territories of Khorasan.

The Persian people appear to have been the first ethnic group to populate the region, but they began mixing with an increasing number of foreign invaders and as a result their proportionate number was reduced.[21] Significant immigrants such as Arabs from the west since the 7th century and Turkic peoples after the Turkic migration from the north in the Middle Ages settled in the region.

The land that used to be referred to as Khorasan in the past is inhabited by a multiethnic society today. The majority are Persians (including Tajiks and some Lurs) and the rest are Pashtuns, Uzbeks, Turkmens, Hazaras, Aymāqs, Baluch, Kurds, Arabs, and others.[21][22]

References

- ^ a b c d "Khurasan", The Encyclopaedia of Islam, page 55. Brill. Retrieved 2010-10-22.

In pre-Islamic and early Islamic times, the term "Khurassan" frequently had a much wider denotation, covering also parts of what are now Soviet Central Asia and Afghanistan; early Islamic usage often regarded everywhere east of western Persia, sc. Djibal or what was subsequently termed 'Irak 'Adjami, as being included in a vast and ill-defined region of Khurasan, which might even extend to the Indus Valley and Sind.

Cite error: The named reference "EI" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b "Khorasan". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

historical region and realm comprising a vast territory now lying in northeastern Iran, southern Turkmenistan, and northern Afghanistan. The historical region extended, along the north, from the Amu Darya (Oxus River) westward to the Caspian Sea and, along the south, from the fringes of the central Iranian deserts eastward to the mountains of central Afghanistan. Arab geographers even spoke of its extending to the boundaries of India.

- ^ André Wink, "Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World", Brill 1990, Vol.1, page 109

- ^ a b c d DehKhoda, "Lughat Nameh DehKhoda", Online version

- ^ Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325-1354 (reprint, illustrated ed.). Routledge. 2004. p. 416. ISBN 0415344735, 9780415344739. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

{{cite book}}:|first1=missing|last1=(help); Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Zahir ud-Din Mohammad Babur (1525). "Events Of The Year 910 (p.4)". Memoirs of Babur. Packard Humanities Institute. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Dabeersiaghi, Commentary on Safarnâma-e Nâsir Khusraw, 6th Ed. Tehran, Zavvâr: 1375 (Solar Hijri Calendar) 235-236

- ^ Humbach, Helmut, and Djelani Davari, "Nāmé Xorāsān", Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz; Persian translation by Djelani Davari, published in Iranian Languages Studies Website

- ^ a b The Encyclopedia of Islam, Brill 1979, Vol.5, page 56: "In Sasanid times, Khurasan was one of the four great provincial satrapies, and was governed from Marw by Ispahbadh.

- ^ a b Ghubar, Mir Ghulam Mohammad (1937). Khorasan, Kabul Printing House. Kabul, Afghanistan.

- ^ Tajikistan Development Gateway from The Development Gateway Foundation - History of Afghanistan LINK

- ^ "42 Buddhist relics discovered in Logar". Maqsood Azizi. Pajhwok Afghan News. August 18, 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ^ "Buddhist remains found in Afghanistan". Press TV. August 17, 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-16.

- ^ Romano, Amy (2003). A Historical Atlas of Afghanistan. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 28. ISBN 0823938638, 9780823938636. Retrieved 2010-10-17.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ "Last Afghan empire". Louis Dupree, Nancy Hatch Dupree and others. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ^ Axworthy, Michael (2006). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. London: I.B. Tauris. p. 50. ISBN 1850437068. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Friedrich Engels (1857). "Afghanistan". Andy Blunden. The New American Cyclopaedia, Vol. I. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- ^ Lazard, G., "Dari", Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ^ Frye, R.N., "Dari", The Encyclopaedia of Islam, CD edition

- ^ Lorentz, J. Historical Dictionary of Iran. 1995 ISBN 0-8108-2994-0AFGJANISTAN

- ^ a b "Khorasan i. Ethnic Groups,"' Pierre Oberling, Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ^ "Khurasan", C.E. Bosworth, The Encyclopaedia of Islam