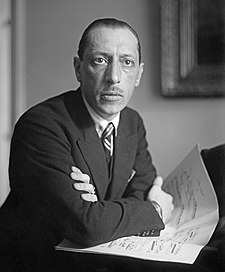

Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (sometimes spelled Strawinski, Strawinsky, or Stravinskii; Russian: И́горь Фёдорович Страви́нский, romanized: Igorʹ Fëdorovič Stravinskij, IPA: [ˈiɡərʲ ˈfʲɵdərəvʲɪtɕ strɐˈvʲinskʲɪj]; 17 June [O.S. 5 June] 1882 – 6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist, and conductor. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the 20th century.

Stravinsky's compositional career was notable for its stylistic diversity. He first achieved international fame with three ballets commissioned by the impresario Sergei Diaghilev and first performed in Paris by Diaghilev's Ballets Russes: The Firebird (1910), Petrushka (1911) and The Rite of Spring (1913). The last of these transformed the way in which subsequent composers thought about rhythmic structure and was largely responsible for Stravinsky's enduring reputation as a musical revolutionary who pushed the boundaries of musical design. His "Russian phase" which continued with works such as Renard, The Soldier's Tale and Les Noces, was followed in the 1920s by a period in which he turned to neoclassical music. The works from this period tended to make use of traditional musical forms (concerto grosso, fugue and symphony), drawing on earlier styles, especially from the 18th century. In the 1950s, Stravinsky adopted serial procedures. His compositions of this period shared traits with examples of his earlier output: rhythmic energy, the construction of extended melodic ideas out of a few two- or three-note cells and clarity of form, and of instrumentation.

Biography

Early life in the Russian Empire

Stravinsky was born on 17 June 1882 in Oranienbaum, a suburb of Saint Petersburg, the Russian imperial capital,[1] and was brought up in Saint Petersburg.[2] His parents were Fyodor Stravinsky, a bass singer at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, and Anna (née Kholodovsky).[3] His great-great-grandfather, Stanisław Strawiński, was of Polish noble descent,[citation needed][clarification needed] of the Strawiński family of Sulima.[4] According to Igor Stravinsky, the name "Stravinsky" originated from "Strava", a small river in eastern Poland, tributary to the Vistula.[5] His family was originally called Soulima-Stravinsky, and they were landowners in eastern Poland as far back as can be traced. After Russia annexed this part of Poland, the Soulima was dropped, and during the reign of Catherine the Great the family moved to Russia.[6] He recalled his schooldays as being lonely, later saying that "I never came across anyone who had any real attraction for me".[7] Stravinsky began piano lessons as a young boy, studying music theory and attempting composition. In 1890, he saw a performance of Tchaikovsky's ballet The Sleeping Beauty at the Mariinsky Theatre. By age fifteen, he had mastered Mendelssohn's Piano Concerto in G minor and finished a piano reduction of a string quartet by Glazunov, who reportedly considered Stravinsky unmusical, and thought little of his skills.[8]

Despite his enthusiasm for music, his parents expected him to study law. Stravinsky enrolled at the University of Saint Petersburg in 1901, but he attended fewer than fifty class sessions during his four years of study.[9] In the summer of 1902 Stravinsky stayed with composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and his family in the German city of Heidelberg, where Rimsky-Korsakov, arguably the leading Russian composer at that time, suggested to Stravinsky that he should not enter the Saint Petersburg Conservatoire, but instead study composing by taking private lessons, in large part because of his age.[10] Stravinsky's father died of cancer that year, by which time his son had already begun spending more time on his musical studies than on law.[11] The university was closed for two months in 1905 in the aftermath of Bloody Sunday:[12] Stravinsky was prevented from taking his final law examinations and later received a half-course diploma in April 1906.[3] Thereafter, he concentrated on studying music. In 1905, he began to take twice-weekly private lessons from Rimsky-Korsakov, whom he came to regard as a second father.[9] These lessons continued until Rimsky-Korsakov's death in 1908.[13]

In 1905 Stravinsky was betrothed to his cousin Yekaterina Gavrilovna Nosenko (called "Katya"), whom he had known since early childhood.[14] In spite of the Orthodox Church's opposition to marriage between first cousins, the couple married on 23 January 1906: their first two children, Fyodor (Theodore) and Ludmila, were born in 1907 and 1908, respectively.[15]

In February 1909, two orchestral works, the [Scherzo fantastique] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) and [Feu d'artifice] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (Fireworks) were performed at a concert in Saint Petersburg, where they were heard by Sergei Diaghilev, who was at that time involved in planning to present Russian opera and ballet in Paris. Diaghilev was sufficiently impressed by Fireworks to commission Stravinsky to carry out some orchestrations and then to compose a full-length ballet score, The Firebird.[16]

Life in Switzerland

Stravinsky became an overnight sensation following the success of The Firebird's premiere in Paris on 25 June 1910.[17]

The composer had travelled from his estate in Ustilug, Ukraine, to Paris in early June to attend the final rehearsals and the premiere of The Firebird.[18] His family joined him before the end of the ballet season and they decided to remain in the West for a time, as his wife was expecting their third child. After spending the summer in La Baule, Brittany, they moved to Switzerland in early September. On the 23rd, their second son Sviatoslav Soulima was born at a maternity clinic in Lausanne; at the end of the month, they took up residence in Clarens.[19]

Over the next four years, Stravinsky and his family lived in Russia during the summer months and spent each winter in Switzerland.[20] During this period, Stravinsky composed two further works for the Ballets Russes: Petrushka (1911), and Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring; 1913).

Shortly following the premiere of The Rite of Spring, Stravinsky contracted typhoid from eating bad oysters, and was confined to a Paris nursing home, unable to depart for Ustilug until 11 July.[21]

During the remainder of the summer, Stravinsky turned his attention to completing his first opera, The Nightingale (usually known by its French title Le Rossignol), which he had begun in 1908 (that is, before his association with the Ballets Russes).[22] The work had been commissioned by the Moscow Free Theatre for the handsome fee of 10,000 roubles.[23]

The Stravinsky family returned to Switzerland (as usual) in the fall of 1913. On 15 January 1914, a fourth child, Marie Milène (or Maria Milena), was born in Lausanne. After her delivery, Katya was discovered to have tuberculosis and confined to the sanatorium at Leysin, high in the Alps. Igor and the family took up residence nearby,[24] and he completed Le Rossignol there on 28 March.[25]

In April, they were finally able to return to Clarens.[26] By then, the Moscow Free Theatre had gone bankrupt.[26] As a result, Le Rossignol was first performed under Diaghilev's auspices at the Paris Opéra on 26 May 1914, with sets and costumes designed by Alexandre Benois.[27] Le Rossignol enjoyed only lukewarm success with the public and the critics, apparently because its delicacy did not meet their expectations of the composer of The Rite of Spring.[25] However, composers including Maurice Ravel, Béla Bartók, and Reynaldo Hahn found much to admire in the score's craftsmanship, even alleging to detect the influence of Arnold Schoenberg.[28]

In July, with war looming, Stravinsky made a quick trip to Ustilug to retrieve personal effects including his reference works on Russian folk music. He returned to Switzerland just before national borders closed following the outbreak of World War I.[29] The War and subsequent Russian Revolution made it impossible for Stravinsky to return to his homeland, and he did not set foot upon Russian soil again until October 1962.[30]

In June 1915, Stravinsky and his family moved from Clarens to Morges, a town 6 miles south-west of Lausanne on the shore of Lake Geneva. The family continued to live there (at three different addresses) until 1920.[31]

Stravinsky struggled financially during this period. Russia (and its successor, the USSR) did not adhere to the Berne Convention and this created problems for Stravinsky when collecting royalties for the performances of all his Ballets Russes compositions.[32] Stravinsky blamed Diaghilev for his financial troubles, accusing him of failing to live up to the terms of a contract they had signed.[11] He approached the Swiss philanthropist Werner Reinhart for financial assistance during the time he was writing L'Histoire du soldat (The Soldier's Tale). Reinhart sponsored and largely underwrote its first performance, conducted by Ernest Ansermet on 28 September 1918 at the Théâtre Municipal de Lausanne.[33] In gratitude, Stravinsky dedicated the work to Reinhart and gave him the original manuscript.[34] Reinhart supported Stravinsky further when he funded a series of concerts of his chamber music in 1919: included was a suite from Histoire du soldat arranged for violin, piano and clarinet,[35] which was first performed on 8 November 1919, in Lausanne.[36] In gratitude to his benefactor, Stravinsky also dedicated his Three Pieces for Clarinet (October–November 1918) to Reinhart, who was an excellent amateur clarinetist.[37]

Life in France

Following the premiere of Pulcinella by the Ballets Russes in Paris on 15 May 1920, Stravinsky returned to Switzerland.[38] On 8 June, the entire family left Morges for the last time, and moved to the fishing village of Carantec in Brittany for the summer while also seeking a new home in Paris.[39] On hearing of their dilemma, couturière Coco Chanel invited Stravinsky and his family to reside at her new mansion "Bel Respiro" in the Paris suburb of Garches until they could find a more suitable residence; they arrived during the second week of September.[40] At the same time, Chanel also guaranteed the new (December 1920) Ballets Russes production of Stravinsky's Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring) with an anonymous gift to Diaghilev, said to have been 300,000 francs.[41]

Stravinsky formed a business and musical relationship with the French piano manufacturing company Pleyel. Pleyel essentially acted as his agent in collecting mechanical royalties for his works and provided him with a monthly income and a studio space at its headquarters in which he could work and entertain friends and business acquaintances.[42] Under the terms of his contract with the company, Stravinsky agreed to arrange (and to some extent re-compose) many of his early works for the Pleyela, Pleyel's brand of player piano.[43] He did so in a way that made full use of all of the piano's eighty-eight notes, without regard for human fingers or hands. The rolls were not recorded, but were instead marked up from a combination of manuscript fragments and handwritten notes by Jacques Larmanjat, musical director of Pleyel's roll department. Among the compositions that were issued on the Pleyela piano rolls are The Rite of Spring, Petrushka, The Firebird and Song of the Nightingale. During the 1920s, Stravinsky recorded Duo-Art rolls for the Aeolian Company in both London and New York, not all of which have survived.[44]

Patronage was never far away. In the early 1920s, Leopold Stokowski gave Stravinsky regular support through a pseudonymous 'benefactor'.[45]

Stravinsky met Vera de Bosset in Paris in February 1921,[46] while she was married to the painter and stage designer Serge Sudeikin, and they began an affair that led to Vera leaving her husband.[47]

In May 1921, Stravinsky and his family moved to Anglet, near Biarritz, southwestern France.[48] From then until his wife's death in 1939, Stravinsky led a double life, dividing his time between his family in Anglet, and Vera in Paris and on tour.[49] Katya reportedly bore her husband's infidelity "with a mixture of magnanimity, bitterness, and compassion".[50]

In September 1924, Stravinsky bought "an expensive house" in Nice: the Villa des Roses.[51]

The Stravinskys became French citizens in 1934 and moved to the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré in Paris.[52] Stravinsky later remembered this last European address as his unhappiest, as his wife's tuberculosis infected both himself and his eldest daughter Ludmila, who died in 1938. Katya, to whom he had been married for 33 years, died of tuberculosis a year later, in March 1939.[53] Stravinsky himself spent five months in hospital, during which time his mother died.[54] During his later years in Paris, Stravinsky had developed professional relationships with key people in the United States: he was already working on his Symphony in C for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra[55] and he had agreed to deliver the prestigious Charles Eliot Norton Lectures at Harvard University during the 1939–40 academic year.[56]

Life in the United States

Despite the outbreak of World War II on 1 September 1939, the widowed Stravinsky sailed (alone) for the United States at the end of the month, arriving in New York City and thence to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to fulfill his engagement at Harvard.[57] Vera followed him in January, and they were married in Bedford, Massachusetts, on 9 March 1940.[58]

Stravinsky settled in West Hollywood.[59] He spent more time living in Los Angeles than any other city.[60] He became a naturalized United States citizen in 1945.[61]

Stravinsky had adapted to life in France, but moving to America at the age of 57 was a very different prospect. For a while, he maintained a circle of contacts and emigré friends from Russia, but he eventually found that this did not sustain his intellectual and professional life. He was drawn to the growing cultural life of Los Angeles, especially during World War II, when so many writers, musicians, composers and conductors settled in the area: these included Otto Klemperer, Thomas Mann, Franz Werfel, George Balanchine and Arthur Rubinstein. Bernard Holland claimed Stravinsky was especially fond of British writers, who visited him in Beverly Hills, "like W. H. Auden, Christopher Isherwood, Dylan Thomas. They shared the composer's taste for hard spirits – especially Aldous Huxley, with whom Stravinsky spoke in French".[60] Stravinsky and Huxley had a tradition of Saturday lunches for west coast avant-garde and luminaries.[62]

Stravinsky's unconventional dominant seventh chord in his arrangement of "The Star-Spangled Banner" led to an incident with the Boston police on 15 January 1944, and he was warned that the authorities could impose a $100 fine upon any "rearrangement of the national anthem in whole or in part".[63][64] The police, as it turned out, were wrong. The law in question merely forbade using the national anthem "as dance music, as an exit march, or as a part of a medley of any kind", but the incident soon established itself as a myth, in which Stravinsky was supposedly arrested, held in custody for several nights, and photographed for police records.[65]

Stravinsky's professional life encompassed most of the 20th century, including many of its modern classical music styles, and he influenced composers both during and after his lifetime. In 1959, he was awarded the Sonning Award, Denmark's highest musical honour. In 1962, he accepted an invitation to return to Leningrad for a series of concerts. During his stay in the USSR, he visited Moscow and met several leading Soviet composers, including Dmitri Shostakovich and Aram Khachaturian.[66]

In 1969, Stravinsky moved to the Essex House in New York, where he lived until his death in 1971 at age 88 of heart failure.[67] He was buried at San Michele, close to the tomb of Sergei Diaghilev.[68]

He has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and in 1987 he was posthumously awarded the Grammy Award for Lifetime Achievement. He was posthumously inducted into the National Museum of Dance's Mr. & Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney Hall of Fame in 2004.

Music

Stravinsky's output is typically divided into three general style periods: a Russian period, a neoclassical period, and a serial period.

Russian Period (c. 1907–1919)

Aside from a very few surviving earlier works, Stravinsky's Russian period began with compositions undertaken under the tutelage of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, with whom he studied from 1905 until Rimsky's death in 1908, including the orchestral works: Symphony in E-flat major (1907), Faun and Shepherdess (for mezzo-soprano and orchestra; 1907), Scherzo fantastique (1908), and Feu d'artifice (1908/9).[69] These works clearly reveal the influence of Rimsky-Korsakov, but as Richard Taruskin has shown, they also reveal Stravinsky's knowledge of music by Glazunov, Taneyev, Tchaikovsky, Wagner, Dvořák, and Debussy, among others.[70]

Performances in St. Petersburg of Scherzo fantastique and Feu d'artifice attracted the attention of Sergei Diaghilev, who commissioned Stravinsky to orchestrate two piano works of Chopin for the ballet Les Sylphides to be presented in the 1909 debut "Saison Russe" of his new ballet company.[71]

The Firebird was first performed at the Paris Opéra on 25 June 1910 by Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. Like Stravinsky's earlier student works, The Firebird continued to look backward to Rimsky-Korsakov not only in its orchestration, but also in its overall structure, harmonic organization, and melodic content.[72]

According to Taruskin, Stravinsky's second ballet for the Ballet Russe, Petrushka, is where "Stravinsky at last became Stravinsky."[73]

The music itself makes significant use of a number of Russian folk tunes in addition to two waltzes by Viennese composer Joseph Lanner and a French music hall tune (La Jambe en bois or The Wooden Leg).[74]

In April 1915, Stravinsky received a commission from Winnaretta Singer (Princesse Edmond de Polignac) for a small-scale theatrical work to be performed in her Paris salon. The result was Renard (1916), which he called "A burlesque in song and dance".[75] Renard was Stravinsky's first venture into experimental theatre: the composer's preface to the score specifies a trestle stage on which all the performers (including the instrumentalists) were to appear simultaneously and continuously. [citation needed]

Neoclassical period (c. 1920–1954)

"Apollon musagète" (1928), "Persephone" (1933) and "Orpheus" (1947) exemplify not only Stravinsky's return to the music of the Classical period, but also his exploration of themes from the ancient Classical world, such as Greek mythology. Important works in this period include the Octet (1923) the Concerto for Piano and Winds (1924) and the Serenade in A (1925). In 1951, he completed his last neo-classical work, the opera "The Rake's Progress," to a libretto by W. H. Auden and Chester Kallman that was based on the etchings of William Hogarth. It premiered in Venice that year and was produced around Europe the following year, before being staged in the New York Metropolitan Opera in 1953.[76] It was staged by the Santa Fe Opera in a 1962 Stravinsky Festival in honor of the composer's 80th birthday and was revived by the Metropolitan Opera in 1997.[citation needed]

Serial period (1954–1968)

In the 1950s, Stravinsky began using serial compositional techniques such as dodecaphony, the twelve-tone technique originally devised by Arnold Schoenberg.[77] He first experimented with non-twelve-tone serial techniques in small-scale vocal and chamber works such as the Cantata (1952), the Septet (1953) and Three Songs from Shakespeare (1953). The first of his compositions fully based on such techniques was In Memoriam Dylan Thomas (1954). Agon (1954–57) was the first of his works to include a twelve-tone series and [Canticum Sacrum] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (1955) was the first piece to contain a movement entirely based on a tone row.[78] Stravinsky expanded his use of dodecaphony in works such as Threni (1958) and A Sermon, a Narrative and a Prayer (1961), which are based on biblical texts,[79] and The Flood (1962), which mixes brief biblical texts from the Book of Genesis with passages from the York and Chester Mystery Plays.[80]

Innovation and influence

Stravinsky has been called "one of music's truly epochal innovators".[81] The most important aspect of Stravinsky's work, aside from his technical innovations (including in rhythm and harmony), is the 'changing face' of his compositional style while always 'retaining a distinctive, essential identity'.[81]

Stravinsky's use of motivic development (the use of musical figures that are repeated in different guises throughout a composition or section of a composition) included additive motivic development. This is where notes are subtracted or added to a motif without regard to the consequent changes in metre. A similar technique can be found as early as the 16th century, for example in the music of Cipriano de Rore, Orlandus Lassus, Carlo Gesualdo and Giovanni de Macque, music with which Stravinsky exhibited considerable familiarity.[82]

The Rite of Spring is notable for its relentless use of ostinati, for example in the eighth-note ostinato on strings accented by eight horns in the section "Augurs of Spring (Dances of the Young Girls)". The work also contains passages where several ostinati clash against one another. Stravinsky was noted for his distinctive use of rhythm, especially in The Rite of Spring.[83] According to the composer Philip Glass, "the idea of pushing the rhythms across the bar lines [...] led the way [...]. The rhythmic structure of music became much more fluid and in a certain way spontaneous".[84] Glass mentions Stravinsky's "primitive, offbeat rhythmic drive".[85] According to Andrew J. Browne, "Stravinsky is perhaps the only composer who has raised rhythm in itself to the dignity of art".[86] Stravinsky's rhythm and vitality greatly influenced the composer Aaron Copland.[87]

Over the course of his career, Stravinsky called for a wide variety of orchestral, instrumental, and vocal forces, ranging from single instruments in such works as Three Pieces for Clarinet (1918) or Elegy for Solo Viola (1944) to the enormous orchestra of The Rite of Spring (Le Sacre du printemps; 1913) which Aaron Copland characterized as "the foremost orchestral achievement of the 20th century."[88]

Stravinsky’s creation of unique and idiosyncratic ensembles arising from the specific musical nature of individual works is a basic element of his style.[citation needed]

Following the model of his teacher, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Stravinsky’s student works such as the Symphony in E-flat, Opus 1 (1907), Scherzo fantastique, Opus 3 (1908), and Fireworks (Feu d'artifice), Opus 4 (1908), call for large orchestral forces. This is not surprising, as the works were as much exercises in orchestration as in composition.[citation needed]

The Symphony, for example, calls for 3 flutes (3rd doubles piccolo); 2 oboes; 3 clarinets in B-flat; 2 bassoons; 4 horns in F; 3 trumpets in B-flat; 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, triangle, cymbals, and strings.[89] The Scherzo fantastique calls for a slightly larger orchestra but completely omits trombones: this was Stravinsky’s response to Rimsky’s criticism of their overuse in the Symphony.[90]

The three ballets composed for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes call for particularly large orchestras. The Firebird (1910) requires winds in fours, 4 horns, 3 trumpets (in A), 3 trombones, tuba, celesta, 3 harps, piano, and strings. The percussion section calls for timpani, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, tambourine, tamtam, tubular bells, glockenspiel, and xylophone. In addition, the original version calls for 3 onstage trumpets and 4 onstage Wagner tubas (2 tenor and 2 bass).[citation needed]

The original version of Petrushka (1911) calls for a similar orchestra (without onstage brass, but with the addition of onstage snare drum). The particularly prominent role of the piano is the result of the music's origin as a Konzertstück for piano and orchestra.[citation needed]

The Rite of Spring (1913) calls for the largest orchestra Stravinsky ever employed: piccolo, 3 flutes (3rd doubles 2nd piccolo), alto flute, 4 oboes (4th doubles 2nd cor anglais), cor anglais, piccolo clarinet in D/E♭, 3 clarinets (3rd doubles 2nd bass clarinet), bass clarinet, piccolo clarinet, 4 bassoons (4th doubles 2nd contrabassoon), contrabassoon, 8 horns (7th and 8th double tenor Wagner tubas), piccolo trumpet in D, 4 trumpets in C (4th doubles bass trumpet in E-flat), 3 trombones (2 tenor, 1 bass), 2 tubas. Percussion includes 5 timpani (2 players), bass drum, tamtam, triangle, tambourine, cymbals, antique cymbals, guiro, and strings. (Piano, celesta, and harp are not included.)[citation needed]

Personality

Stravinsky displayed a taste in literature that was wide and reflected his constant desire for new discoveries. The texts and literary sources for his work began with a period of interest in Russian folklore, which progressed to classical authors and the Latin liturgy and moved on to contemporary France (André Gide, in Persephone) and eventually English literature, including Auden, T. S. Eliot and medieval English verse. He also had an inexhaustible desire to explore and learn about art, which manifested itself in several of his Paris collaborations. Not only was he the principal composer for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, but he also collaborated with Picasso (Pulcinella, 1920), Jean Cocteau ([Oedipus Rex] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), 1927), and George Balanchine ([Apollon musagète] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), 1928). His interest in art propelled him to develop a strong relationship with Picasso, whom he met in 1917, announcing that in "a whirlpool of artistic enthusiasm and excitement I at last met Picasso."[91] From 1917 to 1920, the two engaged in an artistic dialogue in which they exchanged small-scale works of art to each other as a sign of intimacy, which included the famous portrait of Stravinsky by Picasso,[92][failed verification] and Stravinsky's "Sketch of Music for the Clarinet". This exchange was essential to establish how the artists would approach their collaborative space in Pulcinella.[93]

According to Robert Craft, Stravinsky remained a confirmed monarchist throughout his life and loathed the Bolsheviks from the very beginning.[77] In 1930, he remarked, "I don't believe that anyone venerates Mussolini more than I ... I know many exalted personages, and my artist's mind does not shrink from political and social issues. Well, after having seen so many events and so many more or less representative men, I have an overpowering urge to render homage to your Duce. He is the saviour of Italy and – let us hope – Europe". Later, after a private audience with Mussolini, he added, "Unless my ears deceive me, the voice of Rome is the voice of Il Duce. I told him that I felt like a fascist myself... In spite of being extremely busy, Mussolini did me the great honour of conversing with me for three-quarters of an hour. We talked about music, art and politics".[94] When the Nazis placed Stravinsky's works on the list of "Entartete Musik", he lodged a formal appeal to establish his Russian genealogy and declared, "I loathe all communism, Marxism, the execrable Soviet monster, and also all liberalism, democratism, atheism, etc."[95] Towards the end of his life, at Craft's behest, Stravinsky made a return visit to his native country and composed a cantata in Hebrew, travelling to Israel for its performance.[77]

Stravinsky proved adept at playing the part of a 'man of the world', acquiring a keen instinct for business matters and appearing relaxed and comfortable in public. His successful career as a pianist and conductor took him to many of the world's major cities, including Paris, Venice, Berlin, London, Amsterdam and New York and he was known for his polite, courteous and helpful manner. Stravinsky was reputed to have been a philanderer and was rumoured to have had affairs with high-profile partners, such as Coco Chanel. He never referred to it himself, but Chanel spoke about the alleged affair at length to her biographer Paul Morand in 1946; the conversation was published thirty years later.[96] The accuracy of Chanel's claims has been disputed by both Stravinsky's widow, Vera, and by Craft.[97] Chanel's fashion house avers there is no evidence that any affair between Chanel and Stravinsky ever occurred.[98] A fictionalization of the supposed affair formed the basis of the novel Coco and Igor (2002) and a film, Coco Chanel & Igor Stravinsky (2009). Despite these alleged liaisons, Stravinsky was considered a family man and devoted to his children.[99]

Religion

Stravinsky was a devout member of the Russian Orthodox Church during most of his life, remarking at one time that, "Music praises God. Music is well or better able to praise him than the building of the church and all its decoration; it is the Church's greatest ornament".[100]

Although Stravinsky was not outspoken about his faith, he was a deeply religious man throughout some periods of his life. As a child, he was brought up by his parents in the Russian Orthodox Church. Baptized at birth, he later rebelled against the Church and abandoned it by the time he was fourteen or fifteen years old.[101] Throughout the rise of his career he was estranged from Christianity and it was not until he reached his early forties that he experienced a spiritual crisis. After befriending a Russian Orthodox priest, Father Nicholas, after his move to Nice in 1924, he reconnected with his faith. He rejoined the Russian Orthodox Church and afterwards remained a committed Christian.[102] Robert Craft noted that Stravinsky prayed daily, before and after composing, and also prayed when facing difficulty.[103] Towards the end of his life, he was no longer able to attend church services. In his late seventies, Stravinsky said:

I cannot now evaluate the events that, at the end of those thirty years, made me discover the necessity of religious belief. I was not reasoned into my disposition. Though I admire the structured thought of theology (Anselm's proof in the Fides Quaerens Intellectum, for instance) it is to religion no more than counterpoint exercises are to music. I do not believe in bridges of reason or, indeed, in any form of extrapolation in religious matters. ... I can say, however, that for some years before my actual "conversion", a mood of acceptance had been cultivated in me by a reading of the Gospels and by other religious literature.[104]

Reception

If Stravinsky's stated intention was "to send them all to hell",[105] then he may have rated the 1913 premiere of The Rite of Spring as a success: it is a famous classical music riot and Stravinsky referred to it on several occasions in his autobiography as a scandale.[106] There were reports of fistfights in the audience and the need for a police presence during the second act. The real extent of the tumult is open to debate and the reports may be apocryphal.[107] Stravinsky was named by Time magazine as one of the 100 most influential people of the century.[108] In addition to the recognition he received for his compositions, he achieved fame as a pianist and a conductor, often at the premieres of his works. In 1923, Erik Satie wrote an article about Igor Stravinsky in Vanity Fair.[109]

Satie had met Stravinsky for the first time in 1910. In the published article, Satie argued that measuring the "greatness" of an artist by comparing him to other artists, as if speaking about some "truth", is illusory and that every piece of music should be judged on its own merits and not by comparing it to the standards of other composers. That was exactly what Jean Cocteau did when he commented deprecatingly on Stravinsky in his 1918 book, [Le Coq et l'Arlequin] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help).[110]

According to The Musical Times in 1923:

All the signs indicate a strong reaction against the nightmare of noise and eccentricity that was one of the legacies of the war.... What (for example) has become of the works that made up the program of the Stravinsky concert which created such a stir a few years ago? Practically the whole lot are already on the shelf, and they will remain there until a few jaded neurotics once more feel a desire to eat ashes and fill their belly with the east wind.[111]

In 1935, the American composer Marc Blitzstein compared Stravinsky to Jacopo Peri and C.P.E. Bach, conceding that, "there is no denying the greatness of Stravinsky. It is just that he is not great enough".[112] Blitzstein's Marxist position was that Stravinsky's wish to "divorce music from other streams of life", which is "symptomatic of an escape from reality", resulted in a "loss of stamina", naming specifically Apollo, the Capriccio, and Le Baiser de la fée.[113]

The composer Constant Lambert described pieces such as [Histoire du soldat] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) as containing "essentially cold-blooded abstraction".[114] Lambert continued, "melodic fragments in [Histoire du Soldat] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) are completely meaningless themselves. They are merely successions of notes that can conveniently be divided into groups of three, five, and seven and set against other mathematical groups" and he described the cadenza for solo drums as "musical purity...achieved by a species of musical castration". He compared Stravinsky's choice of "the drabbest and least significant phrases" to Gertrude Stein's: "Everyday they were gay there, they were regularly gay there everyday" ("Helen Furr and Georgine Skeene", 1922), "whose effect would be equally appreciated by someone with no knowledge of English whatsoever".[115]

In his 1949 book Philosophy of Modern Music, Theodor W. Adorno described Stravinsky as an acrobat and spoke of hebephrenic and psychotic traits in several of Stravinsky's works. Contrary to a common misconception, Adorno didn't believe the hebephrenic and psychotic imitations that the music was supposed to contain were its main fault, as he pointed out in a postscript that he added later to his book. Adorno's criticism of Stravinsky is more concerned with the "transition to positivity" Adorno found in his neoclassical works.[116] Part of the composer's error, in Adorno's view, was his neo-classicism,[117] but of greater importance was his music's "pseudomorphism of painting", playing off [le temps espace] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (time-space) rather than [le temps durée] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (time-duration) of Henri Bergson.[118] According to Adorno, "one trick characterizes all of Stravinsky's formal endeavors: the effort of his music to portray time as in a circus tableau and to present time complexes as though they were spatial. This trick, however, soon exhausts itself".[119] Adorno maintained that the "rhythmic procedures closely resemble the schema of catatonic conditions. In certain schizophrenics, the process by which the motor apparatus becomes independent leads to infinite repetition of gestures or words, following the decay of the ego".[120]

Stravinsky's reputation in Russia and the USSR rose and fell. Performances of his music were banned from around 1933 until 1962, the year Nikita Khrushchev invited him to the USSR for an official state visit. In 1972, an official proclamation by the Soviet Minister of Culture, Ekaterina Furtseva, ordered Soviet musicians to "study and admire" Stravinsky's music and she made hostility toward it a potential offence.[121]

While Stravinsky's music has been criticized for its range of styles, scholars had "gradually begun to perceive unifying elements in Stravinsky's music" by the 1980s. Earlier writers, such as Aaron Copland, Elliott Carter, Boris de Schloezer, and Virgil Thomson, writing in Modern Music (a quarterly review published between 1925 and 1946), could find only a common "'seriousness' of 'tone' or of 'purpose', 'the exact correlation between the goal and the means', or a dry 'ant-like neatness'".[122]

Stravinsky was honored in 1982 by the United States Postal Service with a 2¢ Great Americans series postage stamp.

Awards

- 1954: Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medal

- 1959: Léonie Sonning Music Prize

- 1963: Sibelius-prize

- Grammy Awards

- 1962: Best Classical Composition by Contemporary Composer (The Flood)[123]

- 1962: Best Classical Performance – Orchestra (The Firebird, Igor Stravinsky conducting Columbia Symphony Orchestra)[123]

- 1962: Best Classical Performance – Instrumental Soloist (with orchestra) (Violin Concerto in D, Isaac Stern; Igor Stravinsky conducting Columbia Symphony Orchestra)[123]

- 1987: Lifetime Achievement (posthumous)

Recordings and publications

Igor Stravinsky found recordings a practical and useful tool in preserving his thoughts on the interpretation of his music. As a conductor of his own music, he recorded primarily for Columbia Records, beginning in 1928 with a performance of the original suite from The Firebird and concluding in 1967 with the 1945 suite from the same ballet.[124] In the late 1940s he made several recordings for RCA Victor at the Republic Studios in Los Angeles. Although most of his recordings were made with studio musicians, he also worked with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Cleveland Orchestra, the CBC Symphony Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the Bavarian Broadcasting Symphony Orchestra.

During his lifetime, Stravinsky appeared on several telecasts, including the 1962 world premiere of The Flood on CBS Television. Although he made an appearance, the actual performance was conducted by Robert Craft.[125] Numerous films and videos of the composer have been preserved.

Stravinsky published a number of books throughout his career, almost always with the aid of a (sometimes uncredited) collaborator. In his 1936 autobiography, Chronicle of My Life, which was written with the help of Walter Nouvel, Stravinsky included his well-known statement that "music is, by its very nature, essentially powerless to express anything at all".[126] With Alexis Roland-Manuel and Pierre Souvtchinsky, he wrote his 1939–40 Harvard University Charles Eliot Norton Lectures, which were delivered in French and first collected under the title [Poétique musicale] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in 1942 and then translated in 1947 as Poetics of Music.[127] In 1959, several interviews between the composer and Robert Craft were published as Conversations with Igor Stravinsky,[128] which was followed by a further five volumes over the following decade. A collection of Stravinsky's writings and interviews under the title Confidences sur la musique (Actes Sud, 2013).

Notes

- ^ Greene 1985, p. 1101.

- ^ White 1979, p. 4.

- ^ a b Walsh 2001.

- ^ Pisalnik 2012; Walsh 2000, [page needed]

- ^ Stravinsky and Craft 1960, p. 17.

- ^ Stravinksy and Craft 1960, p. 6.

- ^ Stravinsky 1962, p. 8.

- ^ Dubal 2001, p. 564.

- ^ a b Dubal 2001, p. 565.

- ^ White 1979, p. 8.

- ^ a b Palmer 1982.

- ^ Walsh 2000, p. 83.

- ^ Stravinsky 1962, p. 24.

- ^ White 1979, p. 5.

- ^ White 1979, pp. 11–12.

- ^ White 1979, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Walsh 2000, pp. 142–43.

- ^ Walsh 2000, p. 140.

- ^ Walsh 2000, p. 145.

- ^ White 1979, p. 33.

- ^ V. Stravinsky and Craft 1978, pp. 100, 102.

- ^ V. Stravinsky and Craft 1978, pp. 111–14.

- ^ V. Stravinsky and Craft 1978, p. 113.

- ^ Walsh 2000, p. 224.

- ^ a b V. Stravinsky and Craft 1978, p. 119.

- ^ a b Walsh 2000, p. 233.

- ^ Walsh 2000, p. 230.

- ^ V. Stravinsky and Craft 1978, p. 120.

- ^ Oliver 1995, p. 74.

- ^ V. Stravinsky and Craft 1978, p. 469.

- ^ V. Stravinsky and Craft 1978, pp. 136–37.

- ^ White 1979, p. 85.

- ^ White 1979, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Keller 2011, p. 456.

- ^ Stravinsky 1962, p. 83.

- ^ White 1979, p. 50.

- ^ Anonymous n.d.

- ^ Walsh 2000, p. 313.

- ^ Walsh 2000, p. 315.

- ^ Walsh 2000, p. 318.

- ^ Walsh 2000, p. 319 and fn 21.

- ^ Compositions for Pianola Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ White 1979, p. 573.

- ^ Lawson 1986, pp. 298–301.

- ^ See "Stravinsky, Stokowski and Madame Incognito", Craft 1992, pp. 73–81.

- ^ Walsh 2000, p. 336.

- ^ Vera de Bosset Sudeikina (Vera Stravinsky) profile at bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ Walsh 2000, p. 329.

- ^ Cooper 2000, p. 306.

- ^ Joseph 2001, p. 73.

- ^ Walsh 2000, p. 193.

- ^ White 1979, pp. 77, 84.

- ^ White 1979, p. 9.

- ^ Stravinsky and Craft 1960, p. 18.

- ^ Joseph 2001, p. 279.

- ^ Walsh 2006, p. 595.

- ^ Stravinsky 1960, [page needed].

- ^ White 1979, p. 93.

- ^ Anonymous 1957.

- ^ a b Holland 2001.

- ^ White 1979, p. 390.

- ^ Anonymous 2010.

- ^ "Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 249, § 9".

- ^ According to Michael Steinberg's liner notes to Stravinsky in America, RCA 09026-68865-2, p. 7, the police "removed the parts from Symphony Hall", quoted in Thom 2007, p. 50.

- ^ Walsh 2006, p. 152.

- ^ White 1979, pp. 146–48.

- ^ "Igor Stravinsky, the Composer, Dead at 88". The New York Times.

- ^ Ruff, Willie (24 July 1991). A Call to Assembly: The Autobiography of a Musical Storyteller. BookBaby. ISBN 9781624888410.

- ^ Walsh 2000, pp. 543–44.

- ^ Taruskin 1996, I:pp. 163–368, chapters 3–5.

- ^ Walsh 2000, p. 122.

- ^ McFarland 1994, [page needed].

- ^ Taruskin 1996, I:662.

- ^ See: "Table I: Folk and Popular Tunes in Petrushka." Taruskin 1996, vol. I, pp. 696–97.

- ^ Stravinsky, Igor. Renard: A Burlesque in Song and Dance [Conductor's Score]. Miami, Florida: Edwin F. Kalmus & Co., Inc.

- ^ Griffiths, Stravinsky, Craft, and Josipovici 1982, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b c Craft 1982, [page needed].

- ^ Straus 2001, p. 4.

- ^ White 1979, p. 510.

- ^ White 1979, p. 517.

- ^ a b AMG 2008. "Igor Stravinsky" biography, AllMusic.

- ^ Stravinsky and Craft 1960, pp. 116–17.

- ^ Simon 2007.

- ^ Simeone, Craft, and Glass 1999.

- ^ Glass & 19989.

- ^ Browne 1930, p. 360.

- ^ BBC Radio 3 programme, "Discovering Music" near 33:30. [full citation needed]

- ^ Copland 1952, p. 37.

- ^ Stravinsky, Igor. Symphony No. 1 [sic]. (Moscow: P. Jurgenson, n.d. [1914]).

- ^ Taruskin 1998, p. 325..

- ^ Walsh 2000, p. 276.

- ^ http://www.ipl.org/div/mushist/twen/stravinsky.htm

- ^ Stravinsky and Craft 1959, [page needed].

- ^ Sachs 1987, p. 168.

- ^ Taruskin and Craft 1989, [page needed].

- ^ Morand 1976, pp. 121–24.

- ^ Davis 2006, p. 439.

- ^ Fact-or-fiction Chanel-Stravinsky affair curtains Cannes. Swiss News, 25 May 2009. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ T. Strawinsky and D. Strawinsky 2004, [page needed].

- ^ "Stravinsky's quotations". Brainyquote.com. 6 April 1971. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ Stravinsky and Craft 1969, p. 198.

- ^ Stravinsky and Craft 1960, p. 51.

- ^ Stravinsky and Craft 1966, pp. 172–75.

- ^ Copeland 1982, p. 565, quoting Stravinsky and Craft 1962, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Wenborn (1985, p. 17) alludes to this comment, without giving a specific source.

- ^ Stravinsky 1936, [page needed].

- ^ See Eksteins 1989, pp. 10–16 for an overview of contradictory reportage of the event by participants and the press.

- ^ Glass 1998.

- ^ Satie 1923.

- ^ Volta 1989, first pages of chapter on contemporaries. [page needed].

- ^ "Occasional Notes", The Musical Times and Singing-Class Circular 64, no. 968 (1 October 1923): 712–15, quotation on 713.

- ^ Blitzstein 1935, p. 330.

- ^ Blitzstein 1935, pp. 346–47.

- ^ Lambert 1936, p. 94.

- ^ Lambert 1936.

- ^ Adorno 2006, p. 167.

- ^ Adorno 1973, pp. 206–209.

- ^ Adorno 1973, pp. 191–93.

- ^ Adorno 1973, p. 195.

- ^ Adorno 1973, p. 178.

- ^ Karlinsky 1985, p. 282.

- ^ Pasler 1983, p. 608.

- ^ a b c "1962 Grammy Awards". Infoplease. 5 March 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ^ "Miniature masterpieces". Fondation Igor Stravinsky. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ "Igor Stravinsky – Flood – Opera". Boosey.com. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ Stravinsky 1936, pp. 91–92.

- ^ The names of uncredited collaborators are given in Walsh 2001.

- ^ Stravinsky and Craft 1959.

References

- Adorno, Theodor. 1973. Philosophy of Modern Music. Translated by Anne G. Mitchell and Wesley V. Blomster. New York: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-0138-4 Original German edition, as [Philosophie der neuen Musik] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr, 1949.

- Adorno, Theodor W. 2006. Philosophy of New Music, translated, edited, and with an introduction by Robert Hullot-Kentor. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-3666-4.

- Anonymous. 1940. "Musical Count". Time Magazine (Monday, 11 March).

- Anonymous. 1944. "Stravinsky Liable to Fine". The New York Times (16 January) (Retrieved 22 June 2010).

- Anonymous. 1957. "Stravinsky Turns 75". Los Angeles Times (3 June). Reprinted in Los Angeles Times "Daily Mirror]" blog (3 June 2007; accessed 9 March 2010).

- Anonymous. 1962. "Life Guide: Salutes to Stravinsky on His 80th; A Funny Faulkner, Farm Tours", Life Magazine (8 June): 17.

- Anonymous. 2010. "Synopsis" of Mary Ann Braubach (dir.). Huxley on Huxley. DVD recording. S.l.: Cinedigm, 2010.

- Anonymous. n.d. "Stravinsky: Histoire du Soldat Suite". Naxosdirect.com (archive from 1 March 2013, accessed 24 January 2016).

- Berry, David Carson. 2006. "Stravinsky, Igor." Europe 1789 to 1914: Encyclopedia of the Age of Industry and Empire, editors-in-chief John Merriman and Jay Winter, 4:2261–63. Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Berry, David Carson. 2008. "The Roles of Invariance and Analogy in the Linear Design of Stravinsky's 'Musick to Heare.'" Gamut 1, no. 1.

- Blitzstein, Marc. 1935. "The Phenomenon of Stravinsky". The Musical Quarterly 21, no. 3 (July): 330–47. Reprinted 1991, The Musical Quarterly 75, no. 4 (Winter): 51–69.

- Browne, Andrew J. 1930. "Aspects of Stravinsky's Work". Music & Letters 11, no. 4 (October): 360–66. Online link accessed 19 November 2007 (subscription access).

- Cocteau, Jean. 1918. Le Coq et l'arlequin: notes de la musique. Paris: Éditions de la Sirène. Reprinted 1979, with a preface by Georges Auric. Paris: Stock. ISBN 2-234-01081-0 English edition, as Cock and Harlequin: Notes Concerning Music, translated by Rollo H. Myers, London: Egoist Press, 1921.

- Cohen, Allen. 2004. Howard Hanson in Theory and Practice. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-313-32135-3.

- Cooper, John Xiros (editor). 2000. T. S. Elliot's Orchestra: Critical Essays on Poetry and Music. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8153-2577-0.

- Copeland, Robert M. 1982. "The Christian Message of Igor Stravinsky". The Musical Quarterly 68, no. 4 (October): 563–79.

- Copland, Aaron. 1952. Music and Imagination. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Craft, Robert. 1982. "Assisting Stravinsky: On a Misunderstood Collaboration". The Atlantic 250, no. 6 (December): 64–74.

- Craft, Robert. 1992. Stravinsky: Glimpses of a Life. London: Lime Tree; New York: St Martins Press. ISBN 0-413-45461-4 (Lime Tree); ISBN 0-312-08896-5 (St.Martins).

- Craft, Robert. 1994. Stravinsky: Chronicle of a Friendship, revised and expanded edition. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 0-8265-1258-5.

- Davis, Mary. 2006. "Chanel, Stravinsky, and Musical Chic". Fashion Theory 10, no. 4 (December): 431–60.

- Dubal, David. 2001. The Essential Canon of Classical Music. New York: North Point Press.

- Eksteins, Modris. 1989. Rites of Spring: The Great War and the Modern Era. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-49856-2. Reprinted 1990, New York: Anchor Books ISBN 0-385-41202-9; reprinted 2000, Boston: Mariner Books ISBN 0-395-93758-2.

- Glass, Philip. 1998. "The Classical Musician Igor Stravinsky" Time (Monday, 8 June).

- Greene, David Mason. 1985. Biographical Encyclopaedia of Composers. New York: Doubleday.

- Griffiths, Paul, Igor Stravinsky, Robert Craft, and Gabriel Josipovici. 1982. Igor Stravinsky: the Rake's Progress. Cambridge Opera Handbooks. Cambridge. London, New York, New Rochelle, Melbourne, and Sydney: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23746-7 (cloth); ISBN 0-521-28199-7 (pbk).

- Hazlewood, Charles. 2003. "Stravinsky—The Firebird Suite". On Discovering Music. BBC Radio 3 (20 December). Archived at Discovering Music: Listening Library, Programmes.

- Holland, Bernard. 2001. "Stravinsky, a Rare Bird Amid the Palms: A Composer in California, at Ease if Not at Home", The New York Times (11 March).

- Joseph, Charles M.. 2001. Stravinsky Inside Out. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07537-3.

- Karlinsky, Simon. 1985. "Searching for Stravinskii's Essence". Russian Review 44, no. 3 (July): 281–87.

- Lambert, Constant. 1936. Music Ho! A Study of Music in Decline. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Lawson, Rex. 1986. "Stravinsky and the Pianola". In Confronting Stravinsky, edited by Jann Pasler. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05403-2.

- Lehrer, Jonah. 2007. Igor Stravinsky and the Source of Music, in his Proust Was a Neuroscientist. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 0-618-62010-9.

- McFarland, Mark 1994. "Leitharmony, or Stravinsky's Musical Characterization in the Firebird". International Journal of Musicology 3:203–33. ISBN 3-631-47484-9.

- Morand, Paul. 1976. L'Allure de Chanel. Paris: Hermann. Nouv. éd. du texte original, Paris: Hermann, 1996. ISBN 2-7056-6316-9. Reprinted, [Paris]: Gallimard, 2009; ISBN 978-2-07-039655-9 English as The Allure of Chanel, translated by Euan Cameron. London: Pushkin Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-901285-98-7 (pbk). Special illustrated ed. London: Pushkin, 2009. ISBN 978-1-906548-10-0 (pbk.).

- Oliver, Michael. 1995. Igor Stravinsky. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-3158-1.

- Page, Tim. 2006. "Classical Music: Great Composers, a Less-Than-Great Poser and an Operatic Impresario". Washington Post (Sunday, 30 July): BW13.

- Palmer, Tony. 1982. Stravinsky: Once at a Border.... (TV documentary film). [UK]: Isolde Films. Issued on DVD, [N.p.]: Kultur Video, 2008. [full citation needed]

- Pasler, Jann. 1983. "Stravinsky and His Craft: Trends in Stravinsky Criticism and Research". The Musical Times 124, no. 1688 ("Russian Music", October): 605–609.

- Pisalnik. 2012. "Polski pomnik za cerkiewnym murem". Rzeczpospolita (10 November; archive from 10 September 2015, accessed 24 January 2016).

- Robinson, Lisa. 2004. "Opera Double Bill Offers Insight into Stravinsky's Evolution". The Juilliard Journal Online 19, no. 7 (April). (No longer accessible as of March 2008.)

- Sachs, Harvey. 1987. Music in Fascist Italy. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Satie, Erik. 1923. "Igor Stravinsky: A Tribute to the Great Russian Composer by an Eminent French Confrère". Vanity Fair (February): 39 & 88.

- Siegmeister, Elie (ed.). 1943. The Music Lover's Handbook. New York: William Morrow and Company.

- Simeone, Lisa, with Robert Craft and Philip Glass. 1999. "Igor Stravinsky" NPR's Performance Today: Milestones of the Millennium (16 April). Washington, DC: National Public Radio. Archive (edited) at NPR Online.

- Simon, Scott. 2007. The Primitive Pulse of Stravinsky's 'Rite of Spring'. With an interview with Marin Alsop recorded on Friday 23 March 2007. NPR Weekend Edition. (Saturday 24 March). Washington, DC: National Public Radio.

- Slim, H. Colin. 2006. "Stravinsky's Four Star-Spangled Banners and His 1941 Christmas Card". The Musical Quarterly 89, nos. 2 and 3 (Summer–Fall): 321–447.

- Slonimsky, Nicolas. 1953. Lexicon of Musical Invective: Critical Assaults on Composers Since Beethoven's Time. New York: Coleman-Ross. Second edition, New York: Coleman-Ross, 1965, reprinted Washington Paperbacks WP-52, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1969, reprinted again Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1974 ISBN 0-295-78579-9, and New York: Norton, 2000 ISBN 0-393-32009-X (pbk).

- Straus, Joseph N. 2001. Stravinsky's Late Music. Cambridge Studies in Music Theory and Analysis 16. Cambridge, New York, Port Melbourne, Madrid, and Cape Town: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80220-2 (cloth) ISBN 0-521-60288-2 (pbk).

- Stravinsky, Igor. 1947. Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. OCLC 155726113.

- Stravinsky, Igor. 1960. Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons. New York: Vintage Books.

- Stravinsky, Igor. 1962. An Autobiography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-00161-X; OCLC 311867794. Originally published in French as Chroniques de ma vie, 2 vols. (Paris: Denoël et Steele, 1935), subsequently translated (anonymously) as Chronicle of My Life. London: Gollancz, 1936. OCLC 1354065. This edition reprinted as Igor Stravinsky An Autobiography, with a preface by Eric Walter White (London: Calder and Boyars, 1975) ISBN 0-7145-1063-7 (cloth); ISBN 0-7145-1082-3 (pbk.). Reprinted again as An Autobiography (1903–1934) (London: Boyars, 1990) ISBN 0-7145-1063-7 (cased); ISBN 0-7145-1082-3 (pbk). Also published as Igor Stravinsky An Autobiography (New York: M. & J. Steuer, 1958).

- Stravinsky, Igor, and Robert Craft. 1959. Conversations with Igor Stravinsky. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. OCLC 896750 Reprinted Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980. ISBN 0-520-04040-6.

- Stravinsky, Igor, and Robert Craft. 1960. Memories and Commentaries. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday. Reprinted 1981, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04402-9 Reprinted 2002, London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-21242-5.

- Stravinsky, Igor, and Robert Craft. 1962. Expositions and Developments. London: Faber & Faber. Reprinted, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1981. ISBN 0-520-04403-7.

- Stravinsky, Igor, and Robert Craft. 1966. Themes and Episodes. New York: A. A. Knopf.

- Stravinsky, Igor, and Robert Craft. 1969. Retrospectives and Conclusions. New York: A. A. Knopf.

- Stravinsky, Vera, and Robert Craft. 1978. Stravinsky in Pictures and Documents. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Strawinsky, Théodore, and Denise Strawinsky. 2004. Catherine and Igor Stravinsky: A Family Chronicle 1906–1940. New York: Schirmer Trade Books; London: Schirmer Books. ISBN 0-8256-7290-2.

- Taruskin, Richard. 1996. Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions: A Biography of the Works Through Mavra. Vol. 1 and Vol. 2. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07099-2.

- Taruskin, Richard, reply by Robert Craft. 1989. "'Jews and Geniuses': An Exchange". New York Review of Books (15 June).

- Thom, Paul. 2007. The Musician as Interpreter. Studies of the Greater Philadelphia Philosophy Consortium 4. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-03198-0.

- Volta, Ornella. 1989. Satie Seen through His Letters. London: Boyars. ISBN 0-7145-2980-X.

- Wallace, Helen. 2007. Boosey & Hawkes, The Publishing Story. London: Boosey & Hawkes. ISBN 978-0-85162-514-0.

- Walsh, Stephen. 2000. Stravinsky. A Creative Spring: Russia and France 1882–1934. London: Jonathan Cape. (excerpt), www.nytimes.com. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- Walsh, Stephen. 2001. "Stravinsky, Igor." New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: MacMillan Publishers.

- Walsh, Stephen. 2006. Stravinsky: The Second Exile: France and America, 1934–1971. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40752-9 (cloth); London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-224-06078-3 (cloth); Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25615-6 (pbk).

- Walsh, Stephen. 2007. "The Composer, the Antiquarian and the Go-between: Stravinsky and the Rosenthals". The Musical Times 148, no. 1898 (Spring): 19–34.

- Wenborn, Neil. 1985. Stravinsky. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-7651-1.

- White, Eric Walter. 1979. Stravinsky: The Composer and His Works, second edition. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03983-1 (cloth) ISBN 0-520-03985-8 (pbk).

Further reading

- Cross, Jonathan. 1999. The Stravinsky Legacy. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56365-9.

- Floirat, Anetta. 2015a. "Chagall and Stravinsky: Parallels Between a Painter and a Musician Convergence of Interests". Academia.edu (April).

- Floirat, Anetta. 2015b. "Chagall and Stravinsky, Different Arts and Similar Solutions to Twentieth-century Challenges". Academia.edu (April).

- Floirat, Anetta. 2016, "The Scythian element of the Russian primitivism, in music and visual arts. Based on the work of three painters (Goncharova, Malevich and Roerich) and two composers (Stravinsky and Prokofiev")

- Goubault, Christian. 1991. Igor Stravinsky. Editions Champion, Musichamp l’essentiel 5, Paris 1991 (with catalogue raisonné and calendar).

- Joseph, Charles M. 2002. Stravinsky and Balanchine, A Journey of Invention. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08712-8.

- Kohl, Jerome. 1979–80. "Exposition in Stravinsky's Orchestral Variations". Perspectives of New Music 18, nos. 1 and 2 (Fall-Winter/Spring Summer): 391–405. doi:10.2307/832991 JSTOR 832991 (subscription access).

- Kirchmeyer, Helmut. 2002. Annotated Catalog of Works and Work Editions of Igor Strawinsky till 1971 - Verzeichnis der Werke und Werkausgaben Igor Strawinskys bis 1971, Leipzig: Publications of the Saxon Academy of Sciences in Leipzig. Extended edition available online since 2015, in English and German.

- Kirchmeyer, Helmut. 1958. Igor Strawinsky. Zeitgeschichte im Persönlichkeitsbild. Regensburg: Bosse-Verlag.

- Kundera, Milan. 1995. Testaments Betrayed: An Essay in Nine Parts, translated by Linda Asher. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-017145-6.

- Kuster, Andrew T. 2005. Stravinsky's Topology. D.M.A. dissertation, University of Colorado at Boulder. Morrisville, NC: Lulu.com. ISBN 1-4116-6458-2.

- Locanto, Massimiliano (ed.) 2014. Igor Stravinsky: Sounds and Gestures of Modernity. Salerno: Brepols. ISBN 978-2-503-55325-2

- McFarland, Mark. 2011. "Igor Stravinsky." In Oxford Bibliographies Online: Music, edited by Bruce Gustavson. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Schaeffner, André. 1931. Strawinsky. Paris: Edition Rieder.

- Stravinsky, Igor. 1982–85. Stravinsky: Selected Correspondence, 3 volumes, edited by Robert Craft. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780394518701 (vol. 1), ISBN 9780394528137 (vol. 2), ISBN 9780394542201 (vol. 3).

- Tappolet, Claude. 1990. Correspondence Ansermet-Strawinsky (1914–1967). Edition complète, 3 Volumes, Georg Edition, Genf.

- van den Toorn, Pieter C. 1987. Stravinsky and the Rite of Spring: The Beginnings of a Musical Language. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and Oxford: University of California Press.

- Vlad, Roman. 1958, 1973, 1983. Strawinsky. Turin: Piccola Biblioteca Einaudi.

- Vlad, Roman. 1960, 1967. Stravinsky. London and New York: Oxford University Press,.

External links

General information

- Free scores by Igor Stravinsky at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- The Stravinsky Foundation website

- A Riotous Premiere, an interactive website about The Rite of Spring from the Keeping Score series by the San Francisco Symphony

- "Huxley on Huxley". Dir. Mary Ann Braubach. Cinedigm, 2010. DVD.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "Discovering Stravinsky". BBC Radio 3.

- "Igor Stravinsky (biography, works, resources)" (in French and English). IRCAM.

- Jews and Geniuses On Stravinsky being a Jew or not and about his antisemitism. See also another response and the original media review by Robert Craft.

- Works by Igor Stravinsky at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Igor Stravinsky at the Internet Archive

- Igor Stravinsky at the Pianola Institute

- Stravinsky and Numerology

- Portrait of Igor Stravinsky conducting – A series of images from the UBC Library Digital Collections depicting the composer rehearsing with the New York Philharmonic.

The Ekstrom Collection of the Diaghilev and Stravinsky Foundation is held by the Victoria and Albert Museum London, Department of Theatre and Performance. A full catalogue and details of access arrangements are available here.

Recordings and videos

- An audio recording made by William Malloch of Stravinsky rehearsing his Symphonies of Wind Instruments in Memory of Debussy (a 1947 recording, first broadcast in 1961)

- An archive recording of a radio program by William Malloch that includes a discussion of how attitudes toward Stravinsky’s music changed through the years. Included are excepts from the The Firebird, Petrouchka and The Rite of Spring recorded from the 1930s to the 1950s by a variety of conductors, including the composer himself.

- Excerpts from sound archives of Stravinsky's works from the Contemporary Music Portal

- Conversation with Igor Stravinsky, 1957: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oJIXobO94Jo

- Stravinsky on The Rite of Spring: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RZEsmbcwngY

- Wikipedia articles needing page number citations from October 2007

- Igor Stravinsky

- 1882 births

- 1971 deaths

- 20th-century American pianists

- 20th-century classical composers

- 20th-century classical pianists

- 20th-century conductors (music)

- American classical composers

- American classical pianists

- American conductors (music)

- American male classical composers

- American opera composers

- American people of Russian descent

- Ballets Russes composers

- Burials at Isola di San Michele

- Composers for piano

- Disease-related deaths in New York

- Grammy Award winners

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Harvard University people

- Honorary Members of the Royal Philharmonic Society

- Imperial Russian emigrants to France

- Imperial Russian emigrants to Switzerland

- Imperial Russian emigrants to the United States

- Jazz-influenced classical composers

- Male opera composers

- Modernist composers

- National Museum of Dance Hall of Fame inductees

- Naturalized citizens of France

- Neoclassical composers

- People from Lomonosov

- People from Saint Petersburg Governorate

- Pupils of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

- Ragtime composers

- Recipients of the Léonie Sonning Music Prize

- Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medallists

- Russian anti-communists

- Russian classical composers

- Russian male classical composers

- Russian classical pianists

- Russian conductors (music)

- Russian monarchists

- Russian opera composers

- Russian Orthodox Christians from the United States

- Russian people of Polish descent

- Twelve-tone and serial composers