Illyrian Provinces

| Illyrian Provinces Provinces illyriennes | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous Province of France | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1809–1814 | |||||||||||||||||||

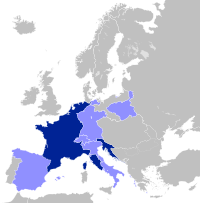

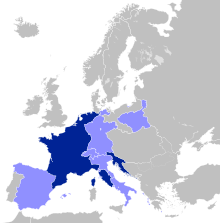

Location of Illyrian Provinces (south-east dark blue) – in the First French Empire (dark blue) – in disputed French territory (light blue) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Laibach (now Ljubljana, Slovenia) Adiminstrative capital Segna (now Senj, Croatia) Military capital | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||||||||||

| • Type | Autonomous Province | ||||||||||||||||||

| Governor-General | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1809–1811 | Auguste de Marmont | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1811–1812 | Henri Bertrand | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1812–1813 | Jean-Andoche Junot | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1813–1814 | Joseph Fouché | ||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Napoleonic Wars | ||||||||||||||||||

| 14 October 1809 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 5 December 1814 | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

The Illyrian Provinces[note 1] was an autonomous province of France during the First French Empire that existed under Napoleonic Rule from 1809 to 1814.[1] The Provinces encompassed modern-day Croatia, Carniola, Slovenia, Gorizia, and parts of Austria. Its headquarters were stationed in Laybach, which would be renamed Ljubljana and made the capital of contemporary Slovenia. It encompassed six départments, making it a relatively large portion of territorial France at the time. Parts of Croatia were split up into Civil Croatia and Military Croatia, the former served as a residential space for French immigrants and Croatian inhabitants and the latter as a military base to check the Ottoman Empire.

In 1809, Napoleon Bonaparte invaded the region with his Grande Armée after key wins during the War of the Fifth Coalition forced the Austrian Empire to cede parts of its territory. Integrating the land into France was Bonaparte's way of controlling Austria's access to the Mediterranean and Adriatic Sea and expanding his empire east. Bonaparte installed four governors to disseminate French bureaucracy, culture, and language. The most famous and influential governor was Auguste de Marmont, who undertook the bulk of Bonaparte's bidding in the area. Marmont was succeeded by Henri Gatien Bertrand (1811-12), Jean-Andoche Junot (1812-13), and Joseph Fouché (1813-14).

Marmont pushed the Code Napoléon throughout the area and led a vast infrastructural expansion. During 1810, the French authorities established the Écoles centrales in Croatia and Slovenia. Although the respective states were allowed to speak and work in their native languages, French was designated as the official language and much of the federal administration was conducted as such. French rule contributed significantly to the provinces even after the Austrian Empire usurped French authority in that area in 1814. Napoleon introduced a greater national self-confidence and awareness of freedoms, as well as numerous political reforms. He introduced equality before the law, compulsory military service, a uniform tax system, abolished certain tax privileges, introduced modern administration, separated church and state and nationalized the judiciary. French presence in this region saw to a diffusion of French culture and the creation of the Illyrian Movement.[2]

Etymology

The use of the name "Illyrian" constitutes a Neoclassicist allusion to the ancient Illyrian tribes who once lived in the region of the Dalmatian coast, known as Illyria in antiquity and Illyricum during the Roman era. In later Greek mythology,[3] Illyrius was the son of Cadmus and Harmonia who eventually ruled Illyria and became the eponymous ancestor of the whole Illyrian people.[4]

History

The Slovene Lands, ruled by the Habsburg Monarchy, were first occupied by the French Revolutionary Army after the Battle of Tarvis in March 1797, led by General Napoleon Bonaparte. The occupation caused huge civil disturbances. The French troops under the command of General Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte tried to calm the worried population by issuing special public notices that were published also in the Slovene language. During the withdrawal of the French army, the commanding general Bonaparte and his escort made a stop in Ljubljana on April 28, 1797. Upon the 1805 Battle of Austerlitz and the Peace of Pressburg, French troops once again occupied parts of Slovene territory. Supply of the French troops and steep war dues were a huge burden for the population of the occupied territories. The foundation of the provincial brigades in June 1808 and extensive preparations for the new war did not stop Napoleon's Grande Armée, which completely defeated the Austrian troops at the Battle of Wagram on July 6, 1809.[5][6]

After the Austrian defeat, the Illyrian Provinces were created by the Treaty of Schönbrunn on 14 October 1809, when the Austrian Empire ceded the territories of western ("Upper") Carinthia with Lienz in the East Tyrol, Carniola, Gorizia and Gradisca, the Imperial Free City of Trieste, the March of Istria, and the Croatian lands southwest of the river Sava to the French Empire. These territories lying north and east of the Adriatic Sea were amalgamated with the former Venetian territories of Dalmatia and Istria, annexed by Austria in the 1797 Treaty of Campo Formio, and the former Republic of Ragusa, which all had just been adjudicated to the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy in 1805 and 1808, into the Illyrian Provinces, technically part of France.[5]

The British Navy imposed a blockade of the Adriatic Sea, effective since the Treaty of Tilsit (July 1807), which brought merchant shipping to a standstill, a measure most seriously affecting the economy of the Dalmatian port cities. An attempt by joint French and Italian forces to seize the British-held Dalmatian island of Vis (Lissa) failed on 22 October 1810.[6][7]

In August 1813, Austria declared war on France. Austrian troops led by General Franz Tomassich invaded the Illyrian Provinces. Croat troops enrolled in the French army switched sides. Zara (now called Zadar) surrendered to Austrian and British forces after a 34-day siege on 6 December 1813. At Dubrovnik an insurrection expelled the French and a provisional Ragusan administration was established, hoping for the restoration of the Republic. It was occupied by Austrian troops on 20 September 1813. The Cattaro area (now called Bay of Kotor) and its environs were occupied in 1813 by Montenegrin forces, which held it until 1814, when the appearance of an Austrian force caused the Prince of Montenegro to turn over the territory to Austrian administration on 11 June. The British withdrew from the occupied Dalmatian islands in July 1815, following the Battle of Waterloo.[6]

Administration

The capital was established at Laybach, i.e. Ljubljana in modern Slovenia. According to Napoleon's Decree on the Organization of Illyria (Decret sur l'organisation de l'Illyrie), issued on April 15, 1811, the Central Government of the Illyrian Provinces (Gouvernement general des provinces d'Illyrie) in Ljubljana consisted of the governor-general (gouverneur-général), the general intendant of finance (intendant général des finances) and the commissioner of the judiciary (commissaire de justice). With two judges of the Appellate Court in Ljubljana they formed the Minor Council (Petit conseil) as the supreme judicial and administrative authority of the Provinces.[8][9]

Subdivision

The area initially consisted of eleven departments, though the subdivision was never completely enacted:

| Name | Capital |

|---|---|

| Adelsberg | Adelsberg (Postojna) |

| Bouches-du-Cattaro | Cattaro (Kotor) |

| Croatie | Karlstadt (Karlovac) |

| Dalmatie | Zara (Zadar) |

| Fiume | Fiume (Rijeka) |

| Gorice | Gorice (Gorizia) |

| Laybach | Laybach (Ljubljana) |

| Neustadt | Neustadt (Novo Mesto) |

| Raguse | Raguse (Dubrovnik) |

| Trieste | Trieste |

| Willach | Willach (Villach) |

In 1811, the Illyrian provinces saw an administrative reorganization, when the country was divided initially in four - Laybach (Ljubljana), Karlstadt (Karlovac), Trieste (Trst), Zara (Zadar) - on 15 April in seven provinces (intendances, similar to French départements). Each province was further subdivided into districts, and these into cantons.[9] A province (intendancy) was governed by a provincial intendant, districts were administered by subdelegates (each district capital that was not a province capital had a subdelegation with a subdelegate, similar to French subprefect) and in cantons justices of the peace had their seats. Municipalities - with municipal council, mayor and deputy mayors in larger municipalities; or council, municipality president-syndic and deputy president-deputy syndic - were units of local government. All officials and councillors were appointed by the emperor or the governor-general, depending on their relevance and/or size of the subdivision unit in which they served.[8]

List of provinces

List of provinces (intendances) and districts:

| Province (Intendancy) |

Capital | Districts |

Former department |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carinthie (Carinthia) |

Willach (Villach) | Willach Lienz |

Willach |

| Carniole (Carniola) |

Laybach (Ljubljana) | Adelsberg (Postojna) Laybach Krainburg (Kranj) Neustadt (Novo Mesto) |

Adelsberg, Laybach, Neustadt |

| Croatie civile (Civil Croatia) |

Karlstadt (Karlovac) |

Karlstadt Fiume (Rijeka) Lussinpiccolo (Mali Lošinj) |

Fiume, parts of Croatie |

| Croatie militaire (Military Croatia) |

Segna (Senj) | parts of Croatie | |

| Istrie (Istria) |

Trieste | Trieste Gorice (Gorizia) Capodistria (Koper) Rovigno (Rovinj) |

Trieste and Gorice |

| Dalmatie (Dalmatia) |

Zara (Zadar) | Zara Spalato (Split) Lesina (Hvar) Sebenico (Šibenik) Macarsca (Makarska) |

Dalmatie |

| Raguse | Raguse (Dubrovnik) | Raguse Cattaro (Kotor) Curzola (Korčula) |

Bouches-du-Cattaro and Raguse |

Two Chambers of Commerce were established, at Trieste and at Ragusa. The ecclesiastical administration was reorganized in accordance with the new political borders; two archdioceses were established with seats at Ljubljana and Zara, with suffragan dioceses at Gorizia, Capodistria, Sebenico, Spalato and Ragusa (1811).[8]

Governors-General

The French administration, headed by a Governor-General, introduced civil law (the Napoleonic Code civil) across the provinces. The seat of the Governor-General was at Laybach. The Governors-General were:

- Auguste de Marmont (8 October 1809 - January 1811)

- Henri Gatien Bertrand (9 April 1811 - 21 February 1813)

- Jean-Andoche Junot (21 February 1813 - July 1813)

- Joseph Fouché (July 1813 - August 1813)

Population

The population (1811) was given at 460,116 for the intendancy of Ljubljana, 381,000 for the intendancy of Karlovac, 357,857 for the intendancy of Trieste and 305,285 for the intendancy of Zara, in total 1,504,258 for all of Illyria. A French decree emancipated the Jews; in effect the decree abolished a Habsburg regulation which had forbidden Jews to settle within Carniola.[6]

Political arrangements

Despite the fact that not all French laws applied to the territory of the Illyrian Provinces, Illyrian offices were accountable to ministries in Paris and to the Higher Court of Paris. Inhabitants of the Illyrian Provinces had Illyrian nationality. Initially the official languages were French, Italian and German, but in 1811 Slovenian was added for the first time in history.[9] Among the main changes the French empire brought were the overhaul of administration, the changing of the schooling system – creating universities and making Slovene a learning language – and the usage of the Napoleonic code (the French Code Civil) and the Penal Code.[6][9] Although the French did not entirely abolish the feudal system, their rule familiarized in more detail the inhabitants of the Illyrian Provinces with the achievements of the French revolution and with contemporary bourgeois society. They introduced equality before the law, compulsory military service and a uniform tax system, and also abolished certain tax privileges, introduced modern administration, separated powers between the state and the church (the introduction of the civil wedding, keeping civil registration of births etc.), and nationalized the judiciary. The occupants made all the citizens theoretically equal under the law for the first time.[9]

The French also founded a university ("École centrale") in 1810 (which was disbanded in 1813, when Austria regained control, but whose Basic Decree of 4 July 1810, which ordered the reorganization of the former Austrian lycees in Ljubljana and Zara into ecoles centrales, is now considered the charter of the University of Ljubljana).[10] They established the first botanic garden at the city’s edge, redesigned the streets and made vaccination of children obligatory. At Karlovac, the headquarters of the Croatian military, a special French-language military school was established in 1811.[9] The linguist Jernej Kopitar and the poet Valentin Vodnik succeeded in instructing the authorities at that time that the language of the inhabitants living in the present-day Slovenian part of the Illyrian Provinces was actually the Slovene language.[9] Although at the time of the Illyrian Provinces the educational reform did not come to life to its fullest ability, it was nevertheless of considerable social significance. The plan for reorganisation of the school system provided for education in elementary and secondary schools in the provincial Slovene language in Slovenian areas. There were 25 gymnasia in the Illyrian provinces.[9]

Proclamations were published in the provinces' official newspaper, Official Telegraph of the Illyrian Provinces (Télégraphe officiel des Provinces Illyriennes). The newspaper was established by Marmont. In 1813, the French author Charles Nodier worked in Ljubljana as the last editor of the journal, significantly renovated it, and published it in French, Italian, and German.[11] The “French gift” of letting the Slovene language be used at school was one of the most important reforms[9] and it won the sympathy of members of the so-called Slovene National Awakening Movement. The Marmont's school reform introduced, in the fall of 1810, a uniform four-year primary school and an extended network of lower and upper gymnasiums and crafts schools. Valentin Vodnik, author of the poem "Illyria Arise", wrote numerous school books for primary schools and lower gymnasiums; since textbooks (and teachers) were scarce, these books made the realization of the idea of Slovene language as a teaching language possible.

Legacy

Although French rule in the Illyrian Provinces was short-lived and did not enjoy the same level of popularity among people, it significantly contributed to greater national self-confidence and awareness of freedoms, especially in the Slovene lands. The opinion of Napoleon's rule and the Illyrian Provinces changed significantly at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, when liberal Croatian and Slovene intellectuals began to praise the French for liberation from Austrian rule.[6][9][12]

It could also be established today that the short period of the Illyrian Provinces was the beginning of a period of an enhanced awareness of the principles of liberty, equality and fraternity.[5][9] The Congress of Vienna confirmed Austria in the possession of the former Illyrian Provinces. In 1816 they were reconstituted without Dalmatia and Croatia, yet now with all of Carinthia, as a Kingdom of Illyria, which was formally abolished only in 1849, even though the civil administration of the Croatian districts had already been placed under Hungarian administration in 1822.[5][9]

The memory of the French and of the Emperor Napoleon is embedded in Croatian and Slovene traditions, in their folk art and folk songs. The presence of the French on Croatian and Slovene territories reflects also in the surnames and house names of French origin, in frescoes, and other paintings depicting French soldiers as well as in rich immovable cultural heritage (roads, bridges, fountains).[5][9] In 1929, a national ceremony was held in Ljubljana during which a monument was erected to Napoleon and Illyria at French Revolution Square. It was filmed by Janko Ravnik.[9]

One of the central streets in Split city centre is named after marshal Marmont, in appreciation of his enlightened rule in Dalmatia.[9]

See also

- List of French possessions and colonies

- Ionian Islands under Venetian rule

- Septinsular Republic

- Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy

Notes

References

- ^ "Illyrian Provinces | historical region, Europe". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

- ^ "Illyrian Provinces | historical region, Europe". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

- ^ E.g. in the myth compendium Bibliotheca of PseudoApollodorus III.5.4, which is not earlier than the first century BC.

- ^ Grimal & Maxwell-Hyslop 1996, p. 230; Apollodorus & Hard 1999, p. 103 (Book III, 5.4)

- ^ a b c d e Malkovic, Goran (2011). Francuski utjecaj. Sveučilišna knjižnica Split. pp. 17, 21, 38.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f "Illyrian Provinces | historical region, Europe". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ^ "Croatian-French relations". Retrieved 2018-03-02.

- ^ a b c "Decret sur l'organisation de l'Illyrie (1811)" (in French). Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Croatian-French relations". Retrieved 2017-05-30.

- ^ Consortium on Revolutionary Europe, 1750-1850, Tallahassee, Fla., University of Florida Press etc, 1990, vol.1, p. 604

- ^ Juvan, Andreja (2003). "Charles Nodier in Ilirija" [Charles Nodier and Illyria]. Kronika: časopis za slovensko krajevno zgodovino (in Slovenian). 51. Section for the History of Places, Union of Historical Societies of Slovenia: 181. ISSN 0023-4923.

- ^ "Croatian-French relations". Retrieved 2018-03-02.

Bibliography

- Bundy, Frank J. (1988). The Administration of the Illyrian Provinces of the French Empire, 1809-1813. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-8240-8032-7.

- Bradshaw, Mary Eloise. (1928). The Napoleonic Influence on the Illyrian Provinces. University of Wisconsin--Madison Press. OCLC: 54803367.

- Bradshaw, Mary Eloise. (1932) The Illyrian Provinces. University of Wisconsin--Madison Press. OCLC: 49491990 .

External links

Media related to Illyrian Provinces at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Illyrian Provinces at Wikimedia Commons

- States and territories established in 1809

- States and territories disestablished in 1814

- Illyrian Provinces

- First French Empire

- Modern history of the Balkans

- History of Dalmatia

- 19th century in Croatia

- 19th century in Montenegro

- Austrian Empire

- 19th century in Italy

- 1809 establishments in Europe

- 1816 disestablishments in Europe

- Former states and territories in Slovenia