Iron fertilization

Iron fertilization is the intentional introduction of iron to the upper ocean to stimulate a phytoplankton bloom. This is intended to enhance biological productivity, which can benefit the marine food chain and is under investigation in hopes of increasing carbon dioxide removal from the atmosphere. Iron is a trace element necessary for photosynthesis in all plants. It is highly insoluble in sea water and is often the limiting nutrient for phytoplankton growth. Large algal blooms can be created by supplying iron to iron-deficient ocean waters.

A number of ocean labs, scientists and businesses are exploring fertilization as a means to sequester atmospheric carbon dioxide in the deep ocean, and to increase marine biological productivity which is hypothesized by some to decline as a result of climate change. Since 1993, thirteen international research teams have completed ocean trials demonstrating that phytoplankton blooms can be stimulated by iron addition.[1] However, controversy remains over the effectiveness of atmospheric CO

2 sequestration and ecological effects.[2] The most recent open ocean trials of ocean iron fertilization were in 2009 (January to March) in the South Atlantic by project Lohafex, and in July 2012 in the North Pacific off the coast of British Columbia, Canada, by the Haida Salmon Restoration Corporation (HSRC).[3]

Fertilization also occurs naturally when upwellings bring nutrient-rich water to the surface, as occurs when ocean currents meet an ocean bank or a sea mount. This form of fertilization produces the world's largest marine habitats. Fertilization can also occur when weather carries wind blown dust long distances over the ocean, or iron-rich minerals are carried into the ocean by glaciers,[4] rivers and icebergs.[5]

History

Consideration of iron's importance to phytoplankton growth and photosynthesis dates back to the 1930s when English biologist Joseph Hart speculated that the ocean's great "desolate zones" (areas apparently rich in nutrients, but lacking in plankton activity or other sea life) might simply be iron deficient.[6] Little further scientific discussion of this issue was recorded until the 1980s, when oceanographer John Martin renewed controversy on the topic with his marine water nutrient analyses. His studies indicated it was indeed a scarcity of iron micronutrients that was limiting phytoplankton growth and overall productivity in these "desolate" regions, which came to be called "High Nutrient, Low Chlorophyll" (HNLC) zones.[6]

In an article in the scientific journal Nature (February 1988; 331 (6157): 570ff.), John Gribbin was the first scientist to publicly suggest that the upcoming greenhouse effect might be reduced by adding large amounts of soluble iron compounds to the oceans of the world as a fertilizer for the aquatic plants.

Martin's famous 1988 quip four months later at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, "Give me a half a tanker of iron and I will give you another ice age",[6][7] drove a decade of research whose findings suggested that iron deficiency was not merely impacting ocean ecosystems, it also offered a key to mitigating climate change as well.

Perhaps the most dramatic support for Martin's hypothesis was seen in the aftermath of the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines. Environmental scientist Andrew Watson analyzed global data from that eruption and calculated that it deposited approximately 40,000 tons of iron dust into the oceans worldwide. This single fertilization event generated an easily observed global decline in atmospheric CO

2 and a parallel pulsed increase in oxygen levels.[8]

Experiments

Martin hypothesized that increasing phytoplankton photosynthesis could slow or even reverse global warming by sequestering enormous volumes of CO

2 in the sea. He died shortly thereafter during preparations for Ironex I,[9] a proof of concept research voyage, which was successfully carried out near the Galapagos Islands in 1993 by his colleagues at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories.[6] Since then 9 international ocean studies have examined the fertilization effects of iron:

- Ironex II, 1995[10]

- SOIREE (Southern Ocean Iron Release Experiment), 1999[11]

- EisenEx (Iron Experiment), 2000[12]

- SEEDS (Subarctic Pacific Iron Experiment for Ecosystem Dynamics Study), 2001[13]

- SOFeX (Southern Ocean Iron Experiments - North & South), 2002[14][15]

- SERIES (Subarctic Ecosystem Response to Iron Enrichment Study), 2002[16]

- SEEDS-II, 2004[17]

- EIFEX (European Iron Fertilization Experiment),[18] A successful experiment conducted in 2004 in a mesoscale ocean eddy in the South Atlantic resulted in a bloom of diatoms a large portion of which died and sank to the ocean floor when iron fertilization was discontinued. In contrast to the LOHAFEX experiment, also conducted in a mesoscale eddy, the ocean in the selected area contained enough dissolved silicon ions for the diatoms to flourish.[19][20][21]

- CROZEX (CROZet natural iron bloom and Export experiment), 2005[22]

- One pilot project planned by Planktos, a U.S. company, was cancelled in 2008 for lack of funding.[23] The company blamed environmental organizations for the failure.[24][25]

- LOHAFEX (Indian and German Iron Fertilization Experiment), 2009 [26][27][28] Despite widespread opposition to LOHAFEX, on 26 January 2009 the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) gave clearance for this fertilization experiment to commence. The experiment was carried out in waters low in silicic acid which is likely to affect the efficacy of carbon sequestration.[29] A 900 square kilometers (350 sq mi) portion of the southwest Atlantic Ocean was fertilized with iron sulfate. A large phytoplankton bloom was triggered, however this bloom did not contain diatoms because the fertilized location was already depleted in silicic acid, an essential nutrient for diatom growth.[29] In the absence of diatoms, a relatively small amount of carbon was sequestered, because other phytoplankton are vulnerable to predation by zooplankton and do not sink rapidly upon death.[29] These poor sequestration results have caused some to suggest that ocean iron fertilization is not an effective carbon mitigation strategy in general. However, prior ocean fertilization experiments in high silica locations have observed much higher carbon sequestration rates because of diatom growth. LOHAFEX has just confirmed that the carbon sequestration potential depends strongly upon careful choice of location.[29]

- HSRC, 2012. The Haida Salmon Restoration Corporation (HSRC) - funded by the Old Massett Haida band and managed by Russ George - conducted an iron fertilization experiment dumping 100 tonnes of iron sulphate into the Pacific Ocean from a fishing boat in an eddy 200 nautical miles west of the islands of Haida Gwaii which resulted in increased algae growth over 10,000 square miles. Critics allege George's actions violated the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the London convention on the dumping of wastes at sea which according to them contain moratoriums on geoengineering experiments.[30][31] On 15 July 2014, all gathered scientific data was made available to the public to support further scientific research.[32]

Science

The maximum possible result from iron fertilization, assuming the most favourable conditions and disregarding practical considerations, is 0.29W/m2 of globally averaged negative forcing,[33] which is almost sufficient to reverse the warming effect of about 1/6 of current levels of anthropogenic CO

2 emissions. It is notable, however, that the addition of silicic acid or choosing the proper location could, at least theoretically, eliminate and exceed all man-made CO

2[citation needed].

Role of iron

About 70% of the world's surface is covered in oceans, and the upper part of these (where light can penetrate) is inhabited by algae. In some oceans, the growth and reproduction of these algae is limited by the amount of iron in the seawater. Iron is a vital micronutrient for phytoplankton growth and photosynthesis that has historically been delivered to the pelagic sea by dust storms from arid lands. This Aeolian dust contains 3–5% iron and its deposition has fallen nearly 25% in recent decades.[34]

The Redfield ratio describes the relative atomic concentrations of critical nutrients in plankton biomass and is conventionally written "106 C: 16 N: 1 P." This expresses the fact that one atom of phosphorus and 16 of nitrogen are required to "fix" 106 carbon atoms (or 106 molecules of CO

2). Recent research has expanded this constant to "106 C: 16 N: 1 P: .001 Fe" signifying that in iron deficient conditions each atom of iron can fix 106,000 atoms of carbon,[35] or on a mass basis, each kilogram of iron can fix 83,000 kg of carbon dioxide. The 2004 EIFEX experiment reported a carbon dioxide to iron export ratio of nearly 3000 to 1. The atomic ratio would be approximately: "3000 C: 58,000 N: 3,600 P: 1 Fe".[36]

Therefore, small amounts of iron (measured by mass parts per trillion) in "desolate" HNLC zones can trigger large phytoplankton blooms. Recent marine trials suggest that one kilogram of fine iron particles may generate well over 100,000 kilograms of plankton biomass. The size of the iron particles is critical, however, and particles of 0.5–1 micrometer or less seem to be ideal both in terms of sink rate and bioavailability. Particles this small are not only easier for cyanobacteria and other phytoplankton to incorporate, the churning of surface waters keeps them in the euphotic or sunlit biologically active depths without sinking for long periods of time.

Atmospheric deposition is an important iron source. Satellite images and data (such as PODLER, MODIS, MSIR)[37][38][39] combined with back-trajectory analyses have been used to identify sources of iron–containing dust. Iron-bearing dusts erode from the soil and are transported by wind. Although most dust sources are situated in the Northern Hemisphere, the largest dust sources are located in northern and southern Africa, North America, central Asia, and Australia.[40]

Heterogeneous chemical reactions in the atmosphere modify the speciation of iron in dust and may affect the bioavailability of deposited iron. The soluble form of iron is much higher in aerosols than in soil (~0.5%).[40][41][42] Several photo-chemical interactions with dissolved organic acids increase iron solubility in aerosols.[43][44] Among these, photochemical reduction of oxalate-bound Fe(III) from iron-containing minerals is important. The process is that the organic ligand forms a surface complex with the Fe (III) metal center of an iron-containing mineral (such as hematite or goethite). On exposure to solar radiation the complex is converted to an excited energy state in which the ligand, acting as bridge and an electron donor, supplies an electron to Fe(III) producing soluble Fe(II).[45][46][47] Consistent with this, several studies documented a distinct diel variation in the concentrations of Fe (II) and Fe(III) in which daytime Fe(II) concentrations exceed those of Fe(III).[48][49][50][51]

Volcanic ash as a source of iron

Large amounts of aeolian (wind deposited) sediment are deposited annually in the world’s oceans. These deposits have long been thought to be the main source of iron to the surface ocean, and therefore the main source of iron for biological productivity. Recent studies suggest that volcanic ash has a significant role in supplying the world’s oceans with iron as well.[52] Volcanic ash is composed of glass shards, pyrogenic minerals, lithic particles, and other forms of ash which release nutrients at different rates depending on structure and the type of reaction caused by contact with water.[53]

Murray et al. recently assessed the relationship between increases of biogenic opal in the sediment record with increased iron accumulation over the last million years.[54] In August 2008, an eruption in the Aleutian Islands, Alaska deposited ash in the nutrient-limited Northeast Pacific. There is strong evidence that this ash and iron deposition resulted in one of the largest phytoplankton blooms observed in the subarctic.[55]

Carbon sequestration

2

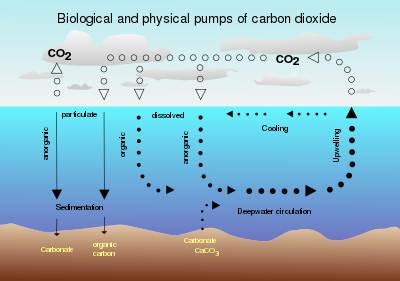

Previous instances of biological carbon sequestration have triggered major climatic changes in which the temperature of the planet was lowered, such as the Azolla event. Plankton that generate calcium or silicon carbonate skeletons, such as diatoms, coccolithophores and foraminifera, account for most direct carbon sequestration. When these organisms die their carbonate skeletons sink relatively quickly and form a major component of the carbon-rich deep sea precipitation known as marine snow. Marine snow also includes fish fecal pellets and other organic detritus, and can be seen steadily falling thousands of meters below active plankton blooms.[56]

Of the carbon-rich biomass generated by plankton blooms, half (or more) is generally consumed by grazing organisms (zooplankton, krill, small fish, etc.) but 20 to 30% sinks below 200 meters (660 ft) into the colder water strata below the thermocline.[citation needed] Much of this fixed carbon continues falling into the abyss, but a substantial percentage is redissolved and remineralized. At this depth, however, this carbon is now suspended in deep currents and effectively isolated from the atmosphere for centuries. (The surface to benthic cycling time for the ocean is approximately 4,000 years.)

Analysis and quantification

Evaluation of the biological effects and verification of the amount of carbon actually sequestered by any particular bloom requires a variety of measurements, including a combination of ship-borne and remote sampling, submarine filtration traps, tracking buoy spectroscopy and satellite telemetry. Unpredictable ocean currents have been known to remove experimental iron patches from the pelagic zone, invalidating the experiment.

The potential of iron fertilization as a climate engineering technique to tackle global warming is illustrated by the following figures. If phytoplankton converted all the nitrate and phosphate present in the surface mixed layer across the entire Antarctic circumpolar current into organic carbon, the resulting carbon dioxide deficit could be compensated by uptake from the atmosphere amounting to about 0.8 to 1.4 gigatonnes of carbon per year.[57] This quantity is comparable in magnitude to annual anthropogenic fossil fuels combustion of approximately 6 gigatonnes. It should be noted that the Antarctic circumpolar current region is only one of several in which iron fertilization could be conducted—the Galapagos islands area being another potentially suitable location.

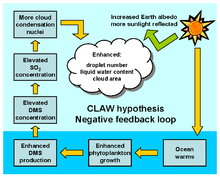

Dimethyl sulfide and clouds

Some species of plankton produce dimethyl sulfide (DMS), a portion of which enters the atmosphere where it is oxidized by hydroxyl radicals (OH), atomic chlorine (Cl) and bromine monoxide (BrO) to form sulfate particles, and potentially increase the cloud cover. This may increase the albedo of the planet and so cause cooling - this proposed mechanism is central to the CLAW hypothesis.[58] This is one of the examples used by James Lovelock to illustrate his Gaia hypothesis.[59]

During the Southern Ocean Iron Enrichment Experiments (SOFeX), DMS concentrations increased by a factor of four inside the fertilized patch. Widescale iron fertilization of the Southern Ocean could lead to significant sulfur-triggered cooling in addition to that due to the increased CO

2 uptake and that due to the ocean's albedo increase, however the amount of cooling by this particular effect is very uncertain.[60]

Financial opportunities

Since the advent of the Kyoto Protocol, several countries and the European Union have established carbon offset markets which trade certified emission reduction credits (CERs) and other types of carbon credit instruments internationally. In 2007 CERs sold for approximately €15–20/ton COe

2.[61] Iron fertilization is relatively inexpensive compared to scrubbing, direct injection and other industrial approaches, and can theoretically sequester for less than €5/ton CO

2, creating a substantial return.[62] In August, 2010, Russia established a minimum price of €10/ton for offsets to reduce uncertainty for offset providers.[63]

Scientists have reported a minimum 6–12% decline in global plankton production since 1980.[34][64] A full-scale international plankton restoration program could regenerate approximately 3–5 billion tons of sequestration capacity worth €50-100 billion in carbon offset value. Given this potential return on investment, carbon traders and offset customers are watching the progress of this technology with interest.[65]

However, a recent study indicates the cost versus benefits of iron fertilization puts it behind carbon capture and storage and carbon taxes.[66]

Multilateral reaction

The parties to the London Dumping Convention adopted a non-binding resolution in 2008 on fertilization (labeled LC-LP.1(2008)). The resolution states that ocean fertilization activities, other than legitimate scientific research, "should be considered as contrary to the aims of the Convention and Protocol and do not currently qualify for any exemption from the definition of dumping".[67]

An Assessment Framework for Scientific Research Involving Ocean Fertilization, regulating the dumping of wastes at sea (labeled LC-LP.2(2010)) was adopted by the Contracting Parties to the Convention in October 2010 (LC 32/LP 5).[68]

Sequestration definitions

Carbon is not considered "sequestered" unless it settles to the ocean floor where it may remain for millions of years. Most of the carbon that sinks beneath plankton blooms is dissolved and remineralized well above the seafloor and will eventually (days to centuries) return to the atmosphere, negating the original effect.[citation needed]

Advocates argue that modern climate scientists and Kyoto Protocol policy makers define sequestration in much shorter time frames. For example, they recognize trees and grasslands as important carbon sinks. Forest biomass only sequesters carbon for decades, but carbon that sinks below the marine thermocline (100–200 meters) is effectively removed from the atmosphere for hundreds of years, whether it is remineralized or not. Since deep ocean currents take so long to resurface, their carbon content is effectively sequestered by the criterion in use today.[citation needed]

Debate

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2009) |

While ocean iron fertilization could represent a potent means to slow global warming current debate raises a variety of concerns.

Precautionary principle

The precautionary principle (PP) states that if an action or policy has a suspected risk of causing harm, in the absence of scientific consensus, the burden of proof that it is not harmful falls on those who would take the action. The side effects of large-scale iron fertilization are not yet known. Creating phytoplankton blooms in naturally iron-poor areas of the ocean is like watering the desert: in effect it changes one type of ecosystem into another.

The argument can be applied in reverse, by considering emissions to be the action and remediation an attempt to partially offset the damage.

20th-century phytoplankton decline

While advocates argue that iron addition would help to reverse a supposed decline in phytoplankton, this decline may not be real. One study reported a decline in ocean productivity comparing the 1979–1986 and 1997–2000 periods,[69] but two others found increases in phytoplankton.[70][71] A study in Nature [2010] of oceanic transparency since 1899 and in situ chlorophyll measurements concluded that oceanic phytoplankton medians have indeed decreased by ~1% per year over the past century.[72]

Comparison to prior phytoplankton cycles

Fertilization advocates respond that similar algal blooms have occurred naturally for millions of years with no observed ill effects. The Azolla event occurred around 49 million years ago and accomplished what fertilization is intended to achieve (but on a larger scale).

Sequestration efficiency

This article duplicates the scope of other articles. (April 2013) |

Fertilization may sequester too little carbon per bloom, supporting the food chain rather than raining on the ocean floor, and thus require too many seeding voyages to be practical.[15][73] In the Lohafex experiment, a 2009 Indo-German team of scientists examined the potential of the south-western Atlantic to sequester significant amounts of carbon dioxide, but found few positive results.[74]

The counter-argument to this is that the low sequestration estimates that emerged from some ocean trials are largely due to these factors:[citation needed]

- Data: none of the ocean trials had enough boat time to monitor their blooms for more than five weeks, confining their measurements to that period. Blooms generally last 60–90 days with the heaviest "precipitation" occurring during the last two months.

- Scale: most trials used less than 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb) of iron and thus created small blooms that were quickly devoured by opportunistic zooplankton, krill, and fish that swarmed into the seeded region.

- Location: some trials have been conducted in locations of the ocean where iron is not the only limiting nutrient. In the 2009 Lohafex experiment, it is believed the lack of carbon sequestration was caused by a shortage of silicic acid in the test area due to previous blooms in the area. Silicic acid is a crucial ingredient needed by Diatoms to grow their shells.[74]

Some ocean trials reported positive results. IronEx II reported conversion of 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb) to carbonaceous biomass equivalent to one hundred full-grown redwoods within two weeks. Eifex recorded fixation ratios of nearly 300,000 to 1.

Current estimates of the amount of iron required to restore all the lost plankton and sequester 3 gigatons/year of CO

2 range widely, from approximately 2 hundred thousand tons/year to over 4 million tons/year. The latter scenario involves 16 supertanker loads of iron and a projected cost of approximately €20 billion ($27 billion).[citation needed]

Ecological issues

Algal blooms

Critics are concerned that fertilization will create harmful algal blooms (HAB). The species that respond most strongly to fertilization vary by location and other factors and could possibly include species that cause red tides and other toxic phenomena. These factors affect only near-shore waters, although they show that increased phytoplankton populations are not universally benign.[citation needed]

Most species of phytoplankton are harmless or beneficial, given that they constitute the base of the marine food chain. Fertilization increases phytoplankton only in the deep oceans (far from shore) where iron deficiency is the problem. Most coastal waters are replete with iron and adding more has no useful effect.[citation needed]

A 2010 study of iron fertilization in an oceanic high-nitrate, low-chlorophyll environment, however, found that fertilized Pseudo-nitzschia diatom spp., which are generally nontoxic in the open ocean, began producing toxic levels of domoic acid. Even short-lived blooms containing such toxins could have detrimental effects on marine food webs.[75]

Deep water oxygen levels

When organic bloom detritus sinks into the abyss, a significant fraction will be devoured by bacteria, other microorganisms and deep sea animals which also consume oxygen. A large enough bloom could render certain regions of the sea deep beneath it anoxic and threaten other benthic species.[citation needed]However this would entail the removal of oxygen from thousands of cubic km of benthic water beneath a bloom and so this seems unlikely.

The largest plankton replenishment projects under consideration are less than 10% the size of most natural wind-fed blooms. In the wake of major dust storms, natural blooms have been studied since the beginning of the 20th century and no such deep water dieoffs have been reported.[citation needed]

Ecosystem effects

Depending upon the composition and timing of delivery, iron infusions could preferentially favor certain species and alter surface ecosystems to unknown effect. Population explosions of jellyfish, that disturb the food chain impacting whale populations or fisheries is unlikely as iron fertilization experiments that are conducted in high-nutrient, low-chlorophyll waters favor the growth of larger diatoms over small flagellates. This has been shown to lead to increased abundance of fish and whales over jellyfish.[76] A 2010 study shows that iron enrichment stimulates toxic diatom production in high-nitrate, low-chlorophyll areas [77] which, the authors argue, raises "serious concerns over the net benefit and sustainability of large-scale iron fertilizations". Whale feces have been referred to as "marine ecosystem engineers". Nitrogen released by cetacean species and iron chelate are a significant benefit to the marine food chain in addition to sequestering carbon for long periods of time.[78]

However, CO

2-induced surface water heating and rising carbonic acidity are already shifting population distributions for phytoplankton, zooplankton and many other creatures. Optimal fertilization could potentially help restore lost/threatened ecosystem services.[citation needed]

Conclusion and further research

Critics and advocates generally agree that most questions on the impact, safety and efficacy of ocean iron fertilization can only be answered by much larger studies.

A statement published in Science in 2008 maintained that it would be

premature to sell carbon offsets from the first generation of commercial-scale OIF experiments unless there is better demonstration that OIF effectively removes CO2, retains that carbon in the ocean for a quantifiable amount of time, and has acceptable and predictable environmental impacts.[79]

See also

References

- ^ Boyd, P.W.; Jickells, T; Law, CS; Blain, S; Boyle, EA; Buesseler, KO; Coale, KH; Cullen, JJ; De Baar, HJ; Follows, M; Harvey, M.; Lancelot, C.; Levasseur, M.; Owens, N. P. J.; Pollard, R.; Rivkin, R. B.; Sarmiento, J.; Schoemann, V.; Smetacek, V.; Takeda, S.; Tsuda, A.; Turner, S.; Watson, A. J.; et al. (2007). "Mesoscale Iron Enrichment Experiments 1993-2005: Synthesis and Future Directions" (PDF). Science. 315 (5812): 612–7. Bibcode:2007Sci...315..612B. doi:10.1126/science.1131669. PMID 17272712.

- ^ Buesseler, K.O.; Doney, SC; Karl, DM; Boyd, PW; Caldeira, K; Chai, F; Coale, KH; De Baar, HJ; Falkowski, PG; Johnson, KS; Lampitt, R. S.; Michaels, A. F.; Naqvi, S. W. A.; Smetacek, V.; Takeda, S.; Watson, A. J.; et al. (2008). "ENVIRONMENT: Ocean Iron Fertilization—Moving Forward in a Sea of Uncertainty" (PDF). Science. 319 (5860): 162. doi:10.1126/science.1154305. PMID 18187642.

- ^ Tollefson, Jeff (2012-10-25). "Ocean-fertilization project off Canada sparks furore". Nature. 490 (7421): 458–459. Bibcode:2012Natur.490..458T. doi:10.1038/490458a. PMID 23099379.

- ^ Smetacek, Victor. "Ocean fertilization" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 29 November 2007 suggested (help) - ^ "Cold Carbon Sink: Slowing Global Warming with Antarctic Iron - SPIEGEL ONLINE". Spiegel.de. 2008-12-18. Retrieved 2012-04-17.

- ^ a b c d Weier, John. "John Martin (1935-1993)". On the Shoulders of Giants. NASA Earth Observatory. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ^ "Ocean Iron Fertilization – Why Dump Iron into the Ocean". Café Thorium. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Archived from the original on 2007-02-10. Retrieved 2007-03-31.

- ^ Watson, A.J. (1997-02-13). "Volcanic iron, CO2, ocean productivity and climate" (PDF). Nature. 385 (6617): 587–588. Bibcode:1997Natur.385R.587W. doi:10.1038/385587b0.

- ^ Ironex (Iron Experiment) I

- ^ Ironex II, 1995

- ^ SOIREE (Southern Ocean Iron Release Experiment), 1999

- ^ EisenEx (Iron Experiment), 2000

- ^ SEEDS (Subarctic Pacific Iron Experiment for Ecosystem Dynamics Study), 2001

- ^ SOFeX (Southern Ocean Iron Experiments - North & South), 2002

- ^ a b "Effects of Ocean Fertilization with Iron To Remove Carbon Dioxide from the Atmosphere Reported" (Press release). Retrieved 2007-03-31.

- ^ SERIES (Subarctic Ecosystem Response to Iron Enrichment Study), 2002

- ^ SEEDS-II, 2004

- ^ EIFEX (European Iron Fertilization Experiment), 2004

- ^ Smetacek, Victor; et al. (18 July 2012). "Deep carbon export from a Southern Ocean iron-fertilized diatom bloom" (Abstract). Nature. 487 (7407): 313–319. Bibcode:2012Natur.487..313S. doi:10.1038/nature11229. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ David Biello (July 18, 2012). "Controversial Spewed Iron Experiment Succeeds as Carbon Sink". Scientific American. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ^ Field test stashes climate-warming carbon in deep ocean; Strategically dumping metal puts greenhouse gas away, possibly for good July 18th, 2012 Science News

- ^ CROZEX (CROZet natural iron bloom and Export experiment), 2005

- ^ Scientists to fight global warming with plankton ecoearth.info 2007-05-21

- ^ Planktos kills iron fertilization project due to environmental opposition mongabay.com 2008-02-19

- ^ Venture to Use Sea to Fight Warming Runs Out of Cash New York Times 2008-02-14

- ^ "LOHAFEX: An Indo-German iron fertilization experiment". Eurekalert.org. Retrieved 2012-04-17.

- ^ Bhattacharya, Amit (2009-01-06). "Tossing iron powder into ocean to fight global warming". The Times Of India.

- ^ "'Climate fix' ship sets sail with plan to dump iron - environment - 09 January 2009". New Scientist. Retrieved 2012-04-17.

- ^ a b c d "Lohafex provides new insights on plankton ecology". Eurekalert.org. Retrieved 2012-04-17.

- ^ Martin Lukacs (October 15, 2012). "World's biggest geoengineering experiment 'violates' UN rules: Controversial US businessman's iron fertilisation off west coast of Canada contravenes two UN conventions". The Guardian. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ Henry Fountain (October 18, 2012). "A Rogue Climate Experiment Outrages Scientists". The New York Times. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ^ http://www.whoi.edu/ocb-fert/page.do?pid=38315

- ^ Lenton, T. M., Vaughan, N. E. (2009). "The radiative forcing potential of different climate geoengineering options" (PDF). Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 9: 2559–2608. doi:10.5194/acpd-9-2559-2009.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Ocean Plant Life Slows Down and Absorbs less Carbon NASA Earth Observatory

- ^ Sunda, W. G., and S. A. Huntsman (1995). "Iron uptake and growth limitation in oceanic and coastal phytoplankton". Mar. Chem. 50: 189–206. doi:10.1016/0304-4203(95)00035-P.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ de Baar H . J. W., Gerringa, L. J. A., Laan, P., Timmermans, K. R (2008). "Efficiency of carbon removal per added iron in ocean iron fertilization". Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 364: 269–282. doi:10.3354/meps07548.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barnaba, F., and G. P. Gobbi (2004). "Aerosol seasonal variability over the Mediterranean region and relative impact of maritime, continental and Saharan dust particles over the basin from MODIS data in the year 2001". Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 4: 4285–4337. doi:10.5194/acpd-4-4285-2004.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ginoux, P., and O. Torres (2003). "Empirical TOMS index for dust aerosol: Applications to model validation and source characterization". J. Geophys. Res. 108: 4534. Bibcode:2003JGRD..108.4534G. doi:10.1029/2003jd003470.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kaufman, Y., I. Koren, L. A. Remer, D. Tanre, P. Ginoux, and S. Fan (2005). "Dust transport and deposition observed from the Terra-MODIS spacecraft over the Atlantic Ocean,". J. Geophys. Res. 101.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Mahowald, Natalie M.; et al. (2005). "Atmospheric global dust cycle and iron inputs to the ocean". Global biogeochemical cycles. 19.4.

- ^ Fung, I. Y., S. K. Meyn, I. Tegen, S. C. Doney, J. G. John, and J. K. B. Bishop (2000). "Iron supply and demand in the upper ocean". Global Biogeochem. Cycles. 14: 697–700. Bibcode:2000GBioC..14..697F. doi:10.1029/2000gb900001.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hand, J. L., N. Mahowald, Y. Chen, R. Siefert, C. Luo, A. Subramaniam, and I. Fung (2004). "Estimates of soluble iron from observations and a global mineral aerosol model: Biogeochemical implications". J. Geophys. Res. 109. Bibcode:2004JGRD..10917205H. doi:10.1029/2004jd004574.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Siefert, Ronald L.; et al. (1994). "Iron photochemistry of aqueous suspensions of ambient aerosol with added organic acids". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 58: 3271–3279. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(94)90055-8.

- ^ Yuegang Zuo and Juerg Hoigne (1992). "Formation of hydrogen peroxide and depletion of oxalic acid in atmospheric water by photolysis of iron (iii)-oxalato complexes". Environmental Science & Technology. 26: 1014–1022. doi:10.1021/es00029a022.

- ^ Siffert, Christophe, and Barbara Sulzberger (1991). "Light-induced dissolution of hematite in the presence of oxalate. A case study". Langmuir. 7.8: 1627–1634. doi:10.1021/la00056a014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Banwart, Steven, Simon Davies, and Werner Stumm (1989). "The role of oxalate in accelerating the reductive dissolution of hematite (α-Fe< sub> 2 O< sub> 3) by ascorbate". Colloids and surfaces. 39.2: 303–309. doi:10.1016/0166-6622(89)80281-1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sulzberger, Barbara, and Hansulrich Laubscher (1995). "Reactivity of various types of iron (III)(hydr) oxides towards light-induced dissolution". Marine Chemistry. 50.1: 103–115. doi:10.1016/0304-4203(95)00030-u.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kieber, R., Skrabal, S., Smith, B., and Willey, (2005). "Organic complexation of Fe (II) and its impact on the redox cycling of iron in rain". Environmental Science & Technology. 39: 1576–1583. doi:10.1021/es040439h.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kieber, R. J., Peake, B., Willey, J. D., and Jacobs ,B (2001b). "Iron speciation and hydrogen peroxide concentrations in New Zealand rainwater". Atmospheric Environment. 35: :6041–6048. doi:10.1016/s1352-2310(01)00199-6.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kieber, R. J., Willey, J. D., and Avery, G. B. (2003). "Temporal variability of rainwater iron speciation at the Bermuda Atlantic Time Series Station". Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 108: 1978–2012. Bibcode:2003JGRC..108.3277K. doi:10.1029/2001jc001031.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Willey, J. D., Kieber, R. J., Seaton, P. J., and Miller, C. (2008). "Rainwater as a source of Fe (II)-stabilizing ligands to seawater". Limnology and Oceanography. 53 (4): 1678–1684. doi:10.4319/lo.2008.53.4.1678.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Duggen, S. et al. 2007. Subduction zone volcanic ash can fertilize the surface ocean and stimulate phytoplankton growth: Evidence from biogeochemical experiments and satellite data. Geophysical Research Letters, Vol. 34.

- ^ Olgun, N. et al. 2011. Surface Ocean Iron Fertilization: The role of airborne volcanic ash from subduction zone and hot spot volcanoes and related iron fluxes into the Pacific Ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, Vol. 25.

- ^ Murray, Richard W., Margaret Leinen and Christopher W. Knowlton. 2012. Links between iron input and opal deposition in the Pleistocene equatorial Pacific Ocean. Nature Geoscience 5: 270–274.

- ^ Hemme, R. et al. 2010. Volcanic ash fuels anomalous plankton bloom in subarctic northeast Pacific. Geophysical Research Letters, Vol. 37.

- ^ Video of extremely heavy amounts of "marine snow" in the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Michael Vecchione, NOAA Fisheries Systematics Lab. Published at Census of Marine Life website

- ^ Schiermeier Q (January 2003). "Climate change: The oresmen". Nature. 421 (6919): 109–10. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..109S. doi:10.1038/421109a. PMID 12520274.

- ^ a b Charlson, R. J., Lovelock, J. E., Andreae, M. O. and Warren, S. G. (1987). "Oceanic phytoplankton, atmospheric sulphur, cloud albedo and climate". Nature. 326 (6114): 655–661. Bibcode:1987Natur.326..655C. doi:10.1038/326655a0.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lovelock, J.E. (2000) [1979]. Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-286218-9.

- ^ Wingenter, Oliver W. (2004-06-08). "Changing concentrations of CO, CH4, C5H8, CH3Br, CH3I, and dimethyl sulfide during the Southern Ocean Iron Enrichment Experiments". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (23). National Academy of Sciences: 8537–8541. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.8537W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0402744101. PMC 423229. PMID 15173582. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Feb 2007 Carbon Update, CO2 Australia

- ^ the Ocean, Scienceline

- ^ Russia sets minimum carbon offset price

- ^ Plankton Found to Absorb Less Carbon Dioxide BBC, 8/30/06

- ^ Recruiting Plankton to Fight Global Warming, New York Times, Business Section, page 1, 5/1/07

- ^ Iron fertilisation sunk as an ocean carbon storage solution University of Sydney press release 12 December 2012 and Harrison, D P IJGW (2013)

- ^ RESOLUTION LC-LP.1 (2008) ON THE REGULATION OF OCEAN FERTILIZATION (PDF). London Dumping Convention. 31 October 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ "Assessment Framework for scientific research involving ocean fertilization agreed". International Maritime Organization. October 20, 2010. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ Gregg WW, Conkright ME, O'Reilly JE, et al. (March 2002). "NOAA-NASA Coastal Zone Color Scanner reanalysis effort". Appl Opt. 41 (9): 1615–28. Bibcode:2002ApOpt..41.1615G. doi:10.1364/AO.41.001615. PMID 11921788.

- ^ (Antoine et al.., 2005)

- ^ Gregg et al.. 2005

- ^ Boyce, Daniel G.; Lewis, Marion R.; Worm, Boris (2010). "Global phytoplankton decline over the past century". Nature. 466 (July 29, 2010): 591–596. doi:10.1038/nature09268. PMID 20671703. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- ^ Basgall, Monte (2004-02-13). "Goal of ocean 'iron fertilization' said still unproved". Retrieved 2006-11-27.

- ^ a b "The Sietch Blog » Ocean Iron Fertilization In Southern Ocean Fails To Capture Significant Carbon". Blog.thesietch.org. Retrieved 2012-04-17.

- ^ Tricka, Charles G., Brian D. Bill, William P. Cochlan, Mark L. Wells, Vera L. Trainer, and Lisa D. Pickell (2010). "Iron enrichment stimulates toxic diatom production in high-nitrate, low-chlorophyll areas". PNAS. 107 (13): 5887–5892. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.5887T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0910579107. PMC 2851856. PMID 20231473.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Parsons, T.R.; Lalli, C.M. (2002). "Jellyfish Population Explosions:Revisiting a Hypothesis of Possible Causes" (PDF). La Mer. 40: 111–121. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ Trick, Charles G. (2010). "Iron enrichment stimulates toxic diatom production in high-nitrate, low-chlorophyll areas". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (13): 5887–5892. doi:10.1073/pnas.0910579107. PMC 2851856. PMID 20231473. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Brown, Joshua E. (12 Oct 2010). "Whale poop pumps up ocean health". Science Daily. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Buesseler, KO (11 January 2008). "Ocean Iron Fertilization -- Moving Forward in a Sea of Uncertainty". Science. 319 (5860): 162. doi:10.1126/science.1154305. PMID 18187642.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

Changing ocean processes

- Global Change and Oceanic Primary Productivity: Effects of Ocean-Atmosphere-Biological Feedbacks - A. J. Miller et al., 2003.

- The Processes of the Ocean's Biological Pump and CO2 Sequestration - Jun Nishioka, 2002.

Micronutrient iron and ocean productivity

- Open Ocean Iron Fertilization for Scientific Study and Carbon Sequestration - K. Coale, 2001.

- Ocean Fertilisation - V. Smetecek, 2004.

- Sequestration of CO2 by Ocean Fertilization - M. Markels and R. Barber, 2001.

- Effect of In-Situ Fertilization on Phytoplankton Growth and Biological Carbon Fixation In the Ocean - T. Yoshimura and D. Tsumune, 2005.

- Stimulating the Ocean Biological Carbon Pump by Iron Fertilization - Jun Nishioka, 2003.

- Iron Fertilization of the Oceans: Reconciliing Commercial Claims with Published Models - P. Lam & S. Chisholm, 2002.

- Coale KH, Johnson KS, Fitzwater SE, et al. (October 1996). "A massive phytoplankton bloom induced by an ecosystem-scale iron fertilization experiment in the equatorial Pacific Ocean". Nature. 383 (6600): 495–501. Bibcode:1996Natur.383..495C. doi:10.1038/383495a0. PMID 18680864.

- Schiermeier Q (April 2004). "Iron seeding creates fleeting carbon sink in Southern Ocean". Nature. 428 (6985): 788. Bibcode:2004Natur.428..788S. doi:10.1038/428788b. PMID 15103342.

- Victor Smetecek (March 1999). "Diatoms and the Ocean Carbon Cycle". Protist. 150 (1): 25–32. doi:10.1016/S1434-4610(99)70006-4. PMID 10724516.

- Kent Cavender-Bares; et al. (March 1999). "Differential Response of Equatorial Pacific Phytoplankton to Iron Fertilization". Limnology and Oceanography. 44 (2): 237–246. doi:10.4319/lo.1999.44.2.0237. JSTOR 2670596.

Ocean biomass carbon sequestration

- J.A. Raven and P.G. Falkowski (June 1999). "Oceanic Sinks for Atmospheric CO2". Plant, Cell and Environment. 22 (6): 741–75. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3040.1999.00419.x.

- Jefferson T. Turner (February 2002). "Zooplankton Fecal Pellets, Marine Snow and Sinking Phytoplankton Blooms" (PDF). Aquatic Microbial Ecology. 27 (1): 57–102. doi:10.3354/ame027057.

- Paul Falkowski; et al. (2003). "4. Phytoplankton and Their Role in Primary, New and Export Production". In Fasham, M. J. R. (ed.). Ocean Biogeochemistry. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-42398-2.

- Markels, M and R T Barber (2001). "Sequestration of CO2 by Ocean Fertilization". Proc 1st Nat. Conf. on Carbon Sequestration. Washington, DC.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help)

Ocean carbon cycle modeling

- Andrew Watson, James Orr (2003). "5. Carbon Dioxide Fluxes in the Global Ocean". In Fasham, M. J. R. (ed.). Ocean Biogeochemistry. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-42398-2.

- J.L. Sarmiento and J.C. Orr (December 1991). "Three-Dimensional Simulations of the Impact of Southern Ocean Nutrient Depletion on Atmospheric CO2 and Ocean Chemistry". Limnology and Oceanography. 36 (8): 1928–50. doi:10.4319/lo.1991.36.8.1928. JSTOR 2837725.

Further reading

Technique

- Ocean Gardening Using Iron Fertilizer

- Iron 'Fertilization' Causes Plankton Bloom - National Science Foundation

- Ocean Carbon Sequestration Abstracts - US Department of Energy

- After the SOIREE: Testing the Limits of Iron Fertilization - NASA

- The Geritol Effect - University of Southern California

- Seeds of Iron to Mitigate Climate Change- treehugger.com

- Dumping Iron - Wired News

Context

- Global Impact of Ocean Nourishment - I.S.F. Jones, Berkeley

- Fertilizing the Ocean with Iron - First article in a six-part series from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution's Oceanus magazine

Debate

- Oschlies, A., W. Koeve, W. Rickels, and K. Rehdanz (2010). "Side effects and accounting aspects of hypothetical large-scale southern ocean iron fertilization". Biogeosciences Discuss. 7 (2): 2949–2995. doi:10.5194/bgd-7-2949-2010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - The Iron Shore Of Science Journalism

- An Open Letter to the Marine Science Community: Has Personal Bias Derailed Science?

- Canadian Fishing at the Grand Banks, Zebra Mussels,and Iron's Effect on Plankton: an example of plausible connections -Chris Yukna (Ecole des Mines, France)

- Basu, Sourish (September 2007). "Oceangoing Iron: A venture to profit from a C02-eating algae bloom riles scientists". Scientific American. Vol. 297, no. 4. Scientific American, Inc. (published October 2007). pp. 23–24. Retrieved 2008-08-04. Note: Only first two paragraphs are available free on-line