Josef Mengele

Josef Mengele | |

|---|---|

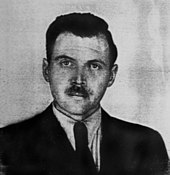

| File:Josef Mengele.jpg Mengele, prior to 1945 | |

| Birth name | Josef Mengele |

| Nickname(s) | Angel of Death (Template:Lang-de)[1] |

| Born | 16 March 1911 Günzburg, Bavaria, German Empire |

| Died | 7 February 1979 (aged 67) Bertioga, São Paulo, Brazil |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1938–45 |

| Rank | |

| Service number | |

| Awards |

|

| Spouse(s) | Irene Schönbein

(m. 1939; div. 1954)Martha Mengele (widow of his brother Karl)

(m. 1958) |

| Signature | |

Josef Mengele (German: [ˈjoːzɛf ˈmɛŋələ] ; 16 March 1911 – 7 February 1979) was a German Schutzstaffel (SS) officer and physician in Auschwitz concentration camp during World War II. Mengele was a notorious member of the team of doctors responsible for the selection of victims to be killed in the gas chambers and for performing deadly human experiments on prisoners. Arrivals deemed able to work were admitted into the camp, and those deemed unfit for labor were immediately killed in the gas chambers. Mengele left Auschwitz on 17 January 1945, shortly before the arrival of the liberating Red Army troops. After the war, he fled to South America, where he evaded capture for the rest of his life.

Mengele received doctorates in anthropology and medicine from Munich University and began a career as a researcher. He joined the Nazi Party in 1937 and the SS in 1938. Initially assigned as a battalion medical officer at the start of World War II, he transferred to the concentration camp service in early 1943 and was assigned to Auschwitz. There he saw the opportunity to conduct genetic research on human subjects. His subsequent experiments, focusing primarily on twins, had no regard for the health or safety of the victims.[2][3]

Assisted by a network of former SS members, Mengele sailed to Argentina in July 1949. He initially lived in and around Buenos Aires, then fled to Paraguay in 1959 and Brazil in 1960 while being sought by West Germany, Israel, and Nazi hunters such as Simon Wiesenthal so that he could be brought to trial. In spite of extradition requests by the West German government and clandestine operations by the Israeli intelligence agency, Mossad, Mengele eluded capture. He drowned while swimming off the Brazilian coast in 1979 and was buried under a false name. His remains were disinterred and positively identified by forensic examination in 1985.

Early life and education

Mengele was born the eldest of three children on 16 March 1911 to Karl and Walburga (Hupfauer) Mengele in Günzburg, Bavaria, Germany.[4] His younger brothers were Karl Jr and Alois. Mengele's father was founder of the Karl Mengele & Sons company, producers of farm machinery.[5] Mengele did well in school and developed an interest in music, art, and skiing.[6] He completed high school in April 1930 and went on to study medicine at Goethe University Frankfurt and philosophy at the University of Munich.[7] Munich was the headquarters of the Nazi Party.[8] In 1931 Mengele joined the Stahlhelm, Bund der Frontsoldaten, a paramilitary organisation that was in 1934 absorbed into the Nazi Sturmabteilung (Storm Detachment; SA).[9][7]

In 1935, Mengele earned a PhD in anthropology from the University of Munich.[7] In January 1937, at the Institute for Hereditary Biology and Racial Hygiene in Frankfurt, he became the assistant to Dr. Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer, a scientist conducting genetics research, with a particular interest in twins.[7] As an assistant to von Verschuer, Mengele focused on the genetic factors resulting in a cleft lip and palate or cleft chin.[10] His thesis on the subject earned him a cum laude doctorate in medicine in 1938.[11] Both of his degrees were later rescinded by the issuing universities.[12] In a letter of recommendation, von Verschuer praised Mengele's reliability and his ability to verbally present complex material in a clear manner.[13] The American author Robert Jay Lifton notes that Mengele's published works did not deviate much from the scientific mainstream of the time, and would probably have been viewed as valid scientific efforts even outside the borders of Nazi Germany.[13]

On 28 July 1939, Mengele married Irene Schönbein, whom he had met while working as a medical resident in Leipzig.[14] Their only son, Rolf, was born in 1944.[15]

Military service

The ideology of Nazism brought together elements of antisemitism, racial hygiene, and eugenics, and combined them with pan-Germanism and territorial expansionism with the goal of obtaining more Lebensraum (living space) for the Germanic people.[16] Nazi Germany attempted to obtain this new territory by attacking Poland and the Soviet Union, intending to deport or kill the Jews and Slavs living there, who were viewed as being inferior to the Aryan master race.[17]

Mengele joined the Nazi Party in 1937 and the Schutzstaffel (SS; protection squadron) in 1938. He received basic training in 1938 with the Gebirgsjäger (mountain infantry) and was called up for service in the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) in June 1940, some months after the outbreak of World War II. He soon volunteered for medical service in the Waffen-SS, the combat arm of the SS, where he served with the rank of SS-Untersturmführer (second lieutenant) in a medical reserve battalion until November 1940. He was next assigned to the SS-Rasse- und Siedlungshauptamt (SS Race and Resettlement Main Office) in Posen, evaluating candidates for Germanisation.[18][19]

In June 1941, Mengele was posted to Ukraine, where he was awarded the Iron Cross Second Class. In January 1942, he joined the 5th SS Panzer Division Wiking as a battalion medical officer. He rescued two German soldiers from a burning tank and was awarded the Iron Cross First Class, as well as the Wound Badge in Black and the Medal for the Care of the German People. He was seriously wounded in action near Rostov-on-Don in mid-1942, and was declared unfit for further active service. After recovery, he was transferred to the Race and Resettlement Office in Berlin. He also resumed his association with von Verschuer, who was at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Genetics and Eugenics. Mengele was promoted to the rank of SS-Hauptsturmführer (captain) in April 1943.[20][21][22]

Auschwitz

In early 1943, encouraged by von Verschuer, Mengele applied for transfer to the concentration camp service, where he foresaw the opportunity to undertake genetic research on human subjects.[20][23] His application was accepted, and he was posted to Auschwitz concentration camp. He was appointed by SS-Standortarzt Eduard Wirths, chief medical officer at Auschwitz, to the position of chief physician of the Zigeunerfamilienlager (Romani family camp), located in the sub-camp at Birkenau.[20][23]

By late 1941, Hitler decided that the Jews of Europe were to be exterminated, so Birkenau, originally intended to house slave laborers, was re-purposed as a combination labor camp / extermination camp.[24][25] Prisoners were transported there by rail from all over German-occupied Europe, arriving in daily convoys.[26] By July 1942, the SS were conducting "selections". Incoming Jews were segregated; those deemed able to work were admitted into the camp, and those deemed unfit for labor were immediately killed in the gas chambers.[27] The group selected to die, about three-quarters of the total,[a] included almost all children, women with small children, pregnant women, all the elderly, and all those who appeared on brief and superficial inspection by an SS doctor not to be completely fit.[29][30] Mengele, a member of the team of doctors assigned to do selections, undertook this work even when he was not assigned to do so in the hope of finding subjects for his experiments.[31] He was particularly interested in locating sets of twins.[32] In contrast to most of the doctors, who viewed undertaking selections as one of their most stressful and horrible duties, Mengele undertook the task with a flamboyant air, often smiling or whistling a tune.[33][34]

Mengele and other SS doctors did not treat inmates, but supervised the activities of inmate doctors forced to work in the camp medical service.[34] Mengele made weekly visits to the hospital barracks and sent to the gas chambers any prisoners who had not recovered after two weeks in bed.[35] He was also a member of the team of doctors responsible for supervising the administration of Zyklon B, the cyanide-based pesticide that was used to kill people in the gas chambers at Birkenau. He served in this capacity at the gas chambers located in crematoria IV and V.[36]

When an outbreak of noma (a gangrenous bacterial disease of the mouth and face) broke out in the Romani camp in 1943, Mengele initiated a study to determine the cause of the disease and develop a treatment. He enlisted the aid of prisoner Dr. Berthold Epstein, a Jewish pediatrician and professor at Prague University. Mengele isolated the patients in a separate barrack and had several afflicted children killed so that their preserved heads and organs could be sent to the SS Medical Academy in Graz and other facilities for study. The research was still ongoing when the Romani camp was liquidated and its remaining occupants killed in 1944.[2]

In response to a typhus epidemic in the women's camp, Mengele cleared one block of 600 Jewish women and sent them to the gas chamber. The building was then cleaned and disinfected, and the occupants of a neighboring block were bathed, de-loused, and given new clothing before being moved into the clean block. The process was repeated until all the barracks were disinfected. Similar disinfections were used for later epidemics of scarlet fever and other diseases, but with all the sick prisoners being sent to the gas chambers. For his efforts, Mengele was awarded the War Merit Cross (Second Class with Swords) and was promoted in 1944 to First Physician of the Birkenau subcamp.[37]

Human experimentation

Mengele used Auschwitz as an opportunity to continue his anthropological studies and research on heredity, using inmates for human experimentation.[2] The experiments had no regard for the health or safety of the victims.[2][3] He was particularly interested in identical twins, people with heterochromia iridum (eyes of two different colours), dwarfs, and people with physical abnormalities.[2] A grant was provided by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, applied for by von Verschuer, who received regular reports and shipments of specimens from Mengele. The grant was used to build a pathology laboratory attached to Crematorium II at Auschwitz II-Birkenau.[38] Dr. Miklós Nyiszli, a Hungarian Jewish pathologist who arrived in Auschwitz on 29 May 1944, performed dissections and prepared specimens for shipment in this laboratory.[39] Mengele's twin research was in part intended to prove the supremacy of heredity over environment and thus bolster the Nazi premise of the superiority of the Aryan race.[40] Nyiszli and others report that the twins studies may also have been motivated by a desire to improve the reproduction rate of the German race by improving the chances of racially desirable people having twins.[41]

Mengele's research subjects were better fed and housed than other prisoners and temporarily safe from the gas chambers.[42] He established a kindergarten for children that were the subjects of experiments, along with all Romani children under the age of six. The facility provided better food and living conditions than other areas of the camp, and even included a playground.[43] When visiting his child subjects, he introduced himself as "Uncle Mengele" and offered them sweets.[44] But he was also personally responsible for the deaths of an unknown number of victims that he killed via lethal injection, shootings, beatings, and through selections and deadly experiments.[45] Lifton describes Mengele as sadistic, lacking empathy, and extremely antisemitic, believing the Jews should be eliminated entirely as an inferior and dangerous race.[46] Mengele's son Rolf said his father later showed no remorse for his wartime activities.[47]

A former Auschwitz prisoner doctor said:

He was capable of being so kind to the children, to have them become fond of him, to bring them sugar, to think of small details in their daily lives, and to do things we would genuinely admire ... And then, next to that, ... the crematoria smoke, and these children, tomorrow or in a half-hour, he is going to send them there. Well, that is where the anomaly lay.[48]

Twins were subjected to weekly examinations and measurements of their physical attributes by Mengele or one of his assistants.[49] Experiments performed by Mengele on twins included unnecessary amputation of limbs, intentionally infecting one twin with typhus or other diseases, and transfusing the blood of one twin into the other. Many of the victims died while undergoing these procedures.[50] After an experiment was over, the twins were sometimes killed and their bodies dissected.[51] Nyiszli recalled one occasion where Mengele personally killed fourteen twins in one night via a chloroform injection to the heart.[34] If one twin died of disease, Mengele killed the other so that comparative post-mortem reports could be prepared.[52]

Mengele's experiments with eyes included attempts to change eye color by injecting chemicals into the eyes of living subjects and killing people with heterochromatic eyes so that the eyes could be removed and sent to Berlin for study.[53] His experiments on dwarfs and people with physical abnormalities included taking physical measurements, drawing blood, extracting healthy teeth, and treatment with unnecessary drugs and X-rays.[3] Many of the victims were sent to the gas chambers after about two weeks, and their skeletons were sent to Berlin for further study.[54] Mengele sought out pregnant women, on whom he would perform experiments before sending them to the gas chambers.[55] Witness Vera Alexander described how he sewed two Romani twins together back to back in an attempt to create conjoined twins.[50] The children died of gangrene after several days of suffering.[56]

After Auschwitz

Along with several other Auschwitz doctors, Mengele transferred to Gross-Rosen concentration camp in Lower Silesia on 17 January 1945. He brought along two boxes of specimens and records of his experiments. Most of the camp medical records had already been destroyed by the SS.[57][58] The Red Army captured Auschwitz on 27 January.[59] Mengele fled Gross-Rosen on 18 February, a week before the Soviets arrived, and traveled westward disguised as a Wehrmacht officer to Saaz (now Žatec). Here he temporarily entrusted his incriminating Auschwitz documents to a nurse with whom he had struck up a relationship.[57] He and his unit hurried west to avoid being captured by the Soviets and were taken prisoner of war by the Americans in June. Mengele was initially registered under his own name, but because of the disorganization of the Allies regarding the distribution of wanted lists and the fact that Mengele did not have the usual SS blood group tattoo, he was not identified as being on the major war criminal list.[60] He was released at the end of July and obtained false papers under the name "Fritz Ullman", documents he later altered to read "Fritz Hollmann".[61]

After several months on the run, including a trip to the Soviet-occupied area to recover his Auschwitz records, Mengele found work near Rosenheim as a farmhand.[62] Worried that his capture would mean a trial and death sentence, he fled Germany on 17 April 1949.[63][64] Assisted by a network of former SS members, Mengele traveled to Genoa, where he obtained a passport under the alias "Helmut Gregor" from the International Committee of the Red Cross. He sailed to Argentina in July.[65] His wife refused to accompany him, and they divorced in 1954.[66]

In South America

In Buenos Aires, Argentina, Mengele worked as a carpenter while residing in a boarding house in the suburb of Vicente Lopez.[67] After a few weeks he moved to the house of a Nazi sympathiser in the more affluent neighborhood of Florida, Buenos Aires. He next worked as a salesman for his family's farm equipment company, and beginning in 1951 he made frequent trips to Paraguay as sales representative for that region.[68] An apartment in the center of Buenos Aires became his residence in 1953, the same year he used family funds to buy a part interest in a carpentry concern. In 1954 he rented a house in the suburb of Olivos.[69] Files released by the Argentine government in 1992 indicate that Mengele may have practiced medicine without a license, including performing abortions, while living in Buenos Aires.[70]

After obtaining a copy of his birth certificate through the West German embassy in 1956, Mengele was issued an Argentine foreign residence permit under his real name. He used this document to obtain a West German passport, also under his real name, and embarked for a visit to Europe.[71][72] He met up in Switzerland for a ski holiday with his son Rolf (who was told Mengele was his "Uncle Fritz"[73]) and his widowed sister-in-law Martha, and spent a week in his home town of Günzburg.[74][75] Upon his return to Argentina in September, Mengele began living under his real name. Martha and her son Karl Heinz followed about a month later, and the three took up residence together. The couple married while on holiday in Uruguay in 1958 and bought a house in Buenos Aires.[71][76] Business interests now included part ownership of Fadro Farm, a pharmaceutical company.[74] Along with several other doctors, Mengele was questioned and released in 1958 under suspicion of practicing medicine without a license after a teenage girl died following an abortion. Worried that the publicity would lead to his Nazi background and wartime activities being discovered, he took an extended business trip to Paraguay and was granted citizenship under the name José Mengele in 1959.[77] He returned to Buenos Aires several times to wrap up his business affairs and visit his family. Martha and Karl Heinz lived in a boarding house in the city until December 1960, when they returned to Germany.[78]

Mengele's name was mentioned several times during the Nuremberg trials, but Allied forces were convinced that he was dead.[79] Irene and the family in Günzburg also said that he was dead.[80] Working in West Germany, Nazi hunters Simon Wiesenthal and Hermann Langbein collected information from witnesses as to Mengele's wartime activities. In a search of the public records, Langbein found Mengele's divorce papers listing an address in Buenos Aires. He and Wiesenthal pressured West German authorities into drawing up an arrest warrant on 5 June 1959, and starting extradition proceedings.[81][82] Initially Argentina turned down the request, because the fugitive was no longer living at the address given on the documents. By the time extradition was approved on 30 June 1960, Mengele had already fled to Paraguay, where he was living on a farm near the Argentine border.[83]

Efforts by the Mossad

In May 1960, Isser Harel, director of the Mossad (the Israeli intelligence agency), personally led the successful effort to capture Adolf Eichmann in Buenos Aires. He hoped to track down Mengele as well so he too could be brought to trial in Israel.[84] Under interrogation, Eichmann provided the address of a boarding house that had been used as a safe house for Nazi fugitives. Surveillance of the house did not reveal Mengele or any members of his family, and the neighborhood postman said that although Mengele had recently been receiving letters there under his real name, he had since relocated, leaving no forwarding address. Harel's inquiries at a machine shop where Mengele had been part owner did not turn up any leads either, so he had to give up.[85]

In spite of having provided Mengele with legal documents in his real name in 1956, thus enabling him to regularize his residency in Argentina, West Germany offered a reward for his capture. Ongoing newspaper coverage of his wartime activities (accompanied by photographs of the fugitive) led Mengele to relocate again in 1960. Former pilot Hans-Ulrich Rudel put him in touch with the Nazi supporter Wolfgang Gerhard, who helped Mengele get across the border into Brazil.[78][86] He stayed with Gerhard on his farm near São Paulo until more permanent accommodations were found with Hungarian expatriates Geza and Gitta Stammer. Helped by an investment from Mengele, the couple bought a farm in Nova Europa, and Mengele was given the job of manager. In 1962 the three bought a coffee and cattle farm in Serra Negra, with Mengele owning a half interest.[87] Initially, Gerhard told the couple that Mengele's name was "Peter Hochbichler", but they discovered his true identity in 1963. Gerhard convinced them not to report Mengele's location to the authorities, saying they could themselves get in trouble for harboring the fugitive.[88] West Germany, tipped off to the possibility that Mengele had relocated there, widened its extradition request to include Brazil in February 1961.[89]

Meanwhile, Zvi Aharoni, one of the Mossad agents who had been involved in the Eichmann capture, was placed in charge of a team of agents tasked with locating Mengele and bringing him to trial in Israel. Inquiries in Paraguay gave no clues as to his whereabouts, and they were unable to intercept any correspondence between Mengele and his wife Martha, then living in Italy. Agents following Rudel's movements did not produce any leads.[90] Aharoni and his team followed Gerhard to a rural area near São Paulo, where they located a European man believed to be Mengele.[91] Aharoni reported his findings to Harel, but the logistics of staging a capture, budgetary constraints, and the need to focus on the nation's deteriorating relationship with Egypt led the Mossad chief to call a halt to the operation in 1962.[92]

Later life and death

Mengele and the Stammers bought a house on a farm in Caieiras in 1969, with Mengele as half owner.[93] When Wolfgang Gerhard returned to Germany in 1971 to seek medical treatment for his seriously ill wife and son, he gave his identity card to Mengele.[94] The Stammers had a falling out with Mengele in late 1974 and bought a house in São Paulo; Mengele was not invited.[b] The Stammers bought a bungalow in the Eldorado neighbourhood of São Paulo, which they rented out to Mengele.[97] Rolf, who had not seen his father since the ski holiday in 1956, visited him there in 1977 and found an unrepentant Nazi who claimed he had never personally harmed anyone and had only done his duty.[98]

Mengele's health had been steadily deteriorating since 1972, and he had a stroke in 1976.[99] He had high blood pressure and an ear infection that affected his balance. While visiting his friends Wolfram and Liselotte Bossert in the coastal resort of Bertioga on 7 February 1979, he suffered another stroke while swimming and drowned.[100] Mengele was buried in Embu das Artes under the name "Wolfgang Gerhard", whose identification card he had been using since 1971.[101]

Other pseudonyms used by Mengele included Dr. Fausto Rindón and S. Josi Alvers Aspiazu.[102]

Exhumation

Meanwhile, Mengele sightings were reported all over the world. Wiesenthal claimed to have information that placed Mengele on the Greek island of Kythnos in 1960,[103] Cairo in 1961,[104] in Spain in 1971,[105] and in Paraguay in 1978, eighteen years after he had left.[106] He insisted as late as 1985—six years after Mengele's death—that he was still alive, in 1982 offering a reward of $100,000 for his capture.[107] Worldwide interest in the case was raised by a mock trial held in Jerusalem in February 1985 featuring the testimony of over a hundred victims of Mengele's experiments. Shortly afterwards, the governments of West Germany, Israel, and the United States launched a coordinated effort to determine Mengele's whereabouts. Rewards for his capture were offered by the Israeli and West German governments, The Washington Times, and the Simon Wiesenthal Center.[108]

On 31 May 1985, acting on a tip received by the West German prosecutor's office, police raided the house of Hans Sedlmeier, a lifelong friend of Mengele and sales manager of the family firm in Günzburg.[109] They found a coded address book and copies of letters to and from Mengele. Among the papers was a letter from Bossert notifying Sedlmeier of Mengele's death.[110] German authorities notified the police in São Paulo, who contacted the Bosserts. Under interrogation, they revealed the location of the grave.[111] The remains were exhumed on 6 June 1985, and extensive forensic examination confirmed with a high degree of probability that the body was Mengele's.[112] Rolf Mengele issued a statement on 10 June admitting that the body was his father's. He said that the news of his father's death had been kept quiet to protect the people who had sheltered his father for so many years.[113] In 1992, DNA testing verified Mengele's identity.[114] The family refused to have the remains repatriated to Germany, and they remain stored at the São Paulo Institute for Forensic Medicine.[115]

Legacy

Mengele's life was the inspiration for a novel and film titled The Boys from Brazil (1978), where a fictional Mengele (portrayed by Gregory Peck[116]) produces clones of Hitler in a clinic in Brazil.[117] In 2007, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum received as a donation the Höcker Album, an album of photographs of Auschwitz staff taken by Karl-Friedrich Höcker. Eight of the photographs include Mengele.[118]

In February 2010, a 180-page volume of Mengele's diary sold by Alexander Autographs at auction for an undisclosed sum to the grandson of a Holocaust survivor. The unidentified previous owner, who acquired the journals in Brazil, was reported to be close to the Mengele family. A Holocaust survivors' organization described the sale as "a cynical act of exploitation aimed at profiting from the writings of one of the most heinous Nazi criminals."[119] Rabbi Marvin Hier of the Simon Wiesenthal Center was glad to see the diary fall into Jewish hands. "At a time when Ahmadinejad's Iran regularly denies the Holocaust and anti-Semitism and hatred of Jews is back in vogue, this acquisition is especially significant," he said.[120] In 2011, a further 31 volumes of Mengele's diaries were sold—again amidst protests—by the same auction house to an undisclosed collector of World War II memorabilia for $245,000.[121]

Mengele's stay in Patagonia was used as the basis of the 2013 Argentinian film The German Doctor with Àlex Brendemühl in the lead role.[122][123]

Summary of SS career

- SS number: 317,885

- Nazi Party number: 5,574,974

- Primary positions: WVHA, Medical Physician (Auschwitz Concentration Camp)

- Waffen-SS Service:

- Medical Staff Officer, Waffen-SS Medical Inspectorate (1940)

- Medical Officer, Pioneer Battalion No. 5, 5th SS Panzer Division Wiking (1941–1943)

- Medical Officer, Battalion "Ost", 3rd SS Division Totenkopf (1943)

Dates of rank

| Mengele's SS-ranks | |

|---|---|

| Date | Rank |

| May 1938[c] | SS-Schütze |

| 1939 | SS-Hauptscharführer der Reserve (d.R.) |

| 1 August 1940 | SS-Untersturmführer d.R. |

| 30 January 1942 | SS-Obersturmführer d.R. |

| 20 April 1943 | SS-Hauptsturmführer d.R. |

Awards

- Iron Cross (First and Second Class)

- War Merit Cross (Second Class with Swords)

- Eastern Front Medal

- Wound Badge (Black)

- Social Welfare Decoration

- German Sports Badge (Bronze)

- Honour Chevron for the Old Guard[d]

Journal articles

- Racial-Morphological Examinations of the Anterior Portion of the Lower Jaw in Four Racial Groups. This dissertation, completed in 1935 and first published in 1937, earned him a PhD in anthropology from Munich University. In this work Mengele sought to demonstrate that there were structural differences in the lower jaws of individuals from different ethnic groups, and that racial distinctions could be made based on these differences.[7][125]

- Genealogical Studies in the Cases of Cleft Lip-Jaw-Palate (1938), his medical dissertation, earned him a doctorate in medicine from Frankfurt University. Studying the influence of genetics as a factor in the occurrence of this deformity, Mengele conducted research on families who exhibited these traits in multiple generations. The work also included notes on other abnormalities found in these family lines.[7][126]

- Hereditary Transmission of Fistulae Auris. This journal article, published in Der Erbarzt (The Genetic Physician), focuses on fistula auris (an abnormal fissure on the external ear) as a hereditary trait. Mengele noted that individuals who have this trait also tend to have a dimple on their chin.[13]

See also

- Nazi eugenics

- Shirō Ishii, director of Imperial Japan's Unit 731 facility in World War II, involved in illegal human experimentation

Notes

- ^ Of the Hungarians who arrived in mid-1944, 85 percent were killed immediately.[28]

- ^ Based on entries in Mengele's journals and interviews with his friends, historians such as Gerald Posner and Gerald Astor believe he had a sexual relationship with Gitta Stammer.[95][96]

- ^ Mengele's enlisted service is mentioned on only a single document of his official SS file. His entry date into the SS is stated to have occurred in early 1938, and by the date of his commissioning in 1940, Mengele was serving as an SS-First Sergeant in the Waffen-SS Reserve.[124]

- ^ Mengele's SS service record indicates this decoration, even though he was not a Nazi Party or SS member prior to 1933, which was a primary requirement for the Old Guard Chevron.[124]

References

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 242.

- ^ a b c d e Kubica 1998, p. 320.

- ^ a b c Astor 1985, p. 102.

- ^ Astor 1985, p. 12.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 4–5. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 6–7. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ a b c d e f Kubica 1998, p. 318.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, p. 81.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 8, 10. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Weindling 2002, p. 53.

- ^ Allison 2011, p. 52.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 234 (footnote).

- ^ a b c Lifton 1986, p. 340.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 11. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 54. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Evans 2008, p. 7.

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 132.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 16. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Kubica 1998, pp. 318–319.

- ^ a b c Kubica 1998, p. 319.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 16–18. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Astor 1985, p. 27.

- ^ a b Allison 2011, p. 53.

- ^ Steinbacher 2005, p. 94.

- ^ Longerich 2010, pp. 282–283.

- ^ Steinbacher 2005, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Rees 2005, p. 100.

- ^ Steinbacher 2005, p. 109.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 235–237.

- ^ Astor 1985, p. 80.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 29. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 27. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ a b c Lifton 1985.

- ^ Astor 1985, p. 78.

- ^ Piper 1998, pp. 170, 172.

- ^ Kubica 1998, pp. 328–329.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 33. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 33–34. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Steinbacher 2005, p. 114.

- ^ Lifton 1986, pp. 358–359.

- ^ Nyiszli 2011, p. 57.

- ^ Kubica 1998, pp. 320–321.

- ^ Lagnado & Dekel 1991, p. 9.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 341.

- ^ Lifton 1986, pp. 376–377.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 48. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Lifton 1985, p. 337.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 350.

- ^ a b Posner & Ware 1986, p. 37. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 351.

- ^ Lifton 1986, pp. 347, 353.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 362.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 360.

- ^ Brozan 1982.

- ^ Mozes-Kor 1992, p. 57.

- ^ a b Levy 2006, p. 255.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 57. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Steinbacher 2005, p. 128.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 63. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 63, 68. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 68, 88. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 87. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 263.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 264–265.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 88, 108. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 95. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 104–105. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 107–108. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Nash 1992.

- ^ a b Levy 2006, p. 267.

- ^ Astor 1985, p. 166.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 2. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ a b Astor 1985, p. 167.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 111. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 112. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 269–270.

- ^ a b Levy 2006, p. 273.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 76, 82. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 261.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 271.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 121. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 269–270, 272.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 139. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 142–143. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 162. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 279–281.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 280, 282.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 168. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 166–167. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 184–186. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 184, 187–188. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 223. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 289.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 178–179. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Astor 1985, p. 224.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 242–243. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 2, 279. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 289, 291.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Blumenthal 1985, p. 1.

- ^ Zentner & Bedürftig 1991, p. 586.

- ^ Segev 2010, p. 167.

- ^ Walters 2009, p. 317.

- ^ Walters 2009, p. 370.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 296.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 297, 301.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 306–308. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 89, 313. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 302.

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 315, 317. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, pp. 319–321. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 322. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPosnerWare1986 (help)

- ^ Saad 2005.

- ^ Simons 1988.

- ^ Turner 2003.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 287.

- ^ USHMM website.

- ^ Oster 2010.

- ^ Hier 2010.

- ^ Aderet 2011.

- ^ ""Wakolda", the film about Mengele in Argentina, chosen as Oscar precandidate". Yahoo! News Spain (in Spanish). 27 September 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ "Oscars: Argentina Nominates 'Wakolda' for Foreign Language Oscar". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ^ a b SS service record, NARA.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 339.

- ^ Lifton 1986, pp. 339–340.

Sources

- Aderet, Ofer (22 July 2011). "Ultra-Orthodox man buys diaries of Nazi doctor Mengele for $245,000". Haaretz. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Allison, Kirk C. (2011). "Eugenics, race hygiene, and the Holocaust: Antecedents and consolidations". In Friedman, Jonathan C (ed.). Routledge History of the Holocaust. Milton Park; New York: Taylor & Francis. pp. 45–58. ISBN 978-0-415-77956-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Astor, Gerald (1985). Last Nazi: Life and Times of Dr Joseph Mengele. New York: Donald I. Fine. ISBN 0-917657-46-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Blumenthal, Ralph (22 July 1985). "Scientists Decide Brazil Skeleton Is Josef Mengele". New York Times. Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brozan, Nadine (15 November 1982). "Out of Death, a Zest for Life". The New York Times.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Evans, Richard J. (2008). The Third Reich at War. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-311671-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hier, Marvin (2010). "Wiesenthal Center Praises Acquisition of Mengele's Diary". Simpn Wiesenthal Center. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06757-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kubica, Helena (1998) [1994]. "The Crimes of Josef Mengele". In Gutman, Yisrael; Berenbaum, Michael (eds.). Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 317–337. ISBN 978-0-253-20884-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lagnado, Lucette Matalon; Dekel, Sheila Cohn (1991). Children of the Flames: Dr Josef Mengele and the Untold Story of the Twins of Auschwitz. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 0-688-09695-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Levy, Alan (2006) [1993]. Nazi Hunter: The Wiesenthal File (Revised 2002 ed.). London: Constable & Robinson. ISBN 978-1-84119-607-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lifton, Robert Jay (21 July 1985). "What Made This Man? Mengele". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lifton, Robert Jay (1986). The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-04905-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mozes-Kor, Eva (1992). "Mengele Twins and Human Experimentation: A Personal Account". In Annas, George J.; Grodin, Michael A. (eds.). The Nazi Doctors and the Nuremberg Code: Human Rights in Human Experimentation. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 53–59. ISBN 978-0-19-510106-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nash, Nathaniel C. (11 February 1992). "Mengele an Abortionist, Argentine Files Suggest". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nyiszli, Miklós (2011) [1960]. Auschwitz: A Doctor's Eyewitness Account. New York: Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61145-011-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Oster, Marcy (3 February 2010). "Survivor's grandson buys Mengele diary". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Piper, Franciszek (1998) [1994]. "Gas Chambers and Crematoria". In Gutman, Yisrael; Berenbaum, Michael (eds.). Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 157–182. ISBN 978-0-253-20884-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Posner, Gerald L.; Ware, John (1986). Mengele: The Complete Story. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-050598-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rees, Laurence (2005). Auschwitz: A New History. New York: Public Affairs. ISBN 1-58648-303-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Saad, Rana (1 April 2005). "Discovery, development, and current applications of DNA identity testing". Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings. 18 (2): 130–133. PMC 1200713. PMID 16200161.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Segev, Tom (2010). Simon Wiesenthal: The Life and Legends. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51946-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Simons, Marlise (17 March 1988). "Remains of Mengele Rest Uneasily in Brazil". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "SS service record of Josef Mengele". College Park, Maryland: National Archives and Records Administration.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Steinbacher, Sybille (2005) [2004]. Auschwitz: A History. Munich: Verlag C. H. Beck. ISBN 0-06-082581-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "The Album". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Turner, Adrian (14 June 2003). "Gregory Peck: Elder statesman of the screen who stood for nobility, honour and decency". The Independent. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walters, Guy (2009). Hunting Evil: The Nazi War Criminals Who Escaped and the Quest to Bring Them to Justice. New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 978-0-7679-2873-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Weindling, Paul (2002). "The Ethical Legacy of Nazi Medical War Crimes: Origins, Human Experiments, and International Justice". In Burley, Justine; Harris, John (eds.). A Companion to Genethics. Blackwell Companions to Philosophy. Malden, MA; Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 53–69. doi:10.1002/9780470756423.ch5. ISBN 0-631-20698-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zentner, Christian; Bedürftig, Friedemann (1991). The Encyclopedia of the Third Reich. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-897502-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Harel, Isser (1975). The House on Garibaldi Street: the First Full Account of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-38028-8.

- Levin, Ira (1991). The Boys from Brazil. London: Bantam. ISBN 0-553-29004-5.

- Lieberman, Herbert A. (1978). The Climate of Hell. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-82236-5.

External links

- Breitman, Richard (April 2001). "Historical Analysis of 20 Name Files from CIA Records". US National Archives.

- Office of Special Investigations, Criminal Division (October 1992). "In the Matter of Josef Mengele: A Report to the Attorney General of the United States" (PDF). United States Department of Justice.

- Papanayotou, Vivi (18 September 2005). "Skeletons in the Closet of German Science". Deutsche Welle.

- Posner, Gerald; Ware, John (18 May 1986). "How Nazi war criminal Josef Mengele cheated justice for 34 years". Chicago Tribune Magazine.

- 1911 births

- 1979 deaths

- 20th-century German writers

- Accidental deaths in Brazil

- Auschwitz concentration camp personnel

- Combat medics

- Deaths by drowning

- German eugenicists

- German expatriates in Argentina

- German expatriates in Brazil

- German medical writers

- German military personnel of World War II

- German military physicians

- German murderers of children

- Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich alumni

- Nazi human subject research

- Nazi physicians

- Nazis in South America

- People from Günzburg

- People from the Kingdom of Bavaria

- Porajmos perpetrators

- Recipients of the Honour Chevron for the Old Guard

- Recipients of the Iron Cross (1939), 1st class

- Recipients of the War Merit Cross, 2nd class

- SS-Hauptsturmführer

- Waffen-SS personnel

- 20th-century physicians

- German male writers

- Genocide perpetrators