Tsardom of Bulgaria (1908–1946)

Tsardom of Bulgaria Царство България Tsarstvo Bŭlgariya | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1908–1946 | |||||||||||||

| Motto: God is with us Бог е с нас (Bulgarian) Bog e s nas (transliteration) | |||||||||||||

| Anthem: "Maritsa Rushes" Шуми Марица (Bulgarian) Shumi Maritsa (transliteration) Royal anthem "Anthem of His Majesty the Tsar" Химн на Негово Величество Царя (Bulgarian) Himn na Negovo Velichestvo Tsarya (transliteration) | |||||||||||||

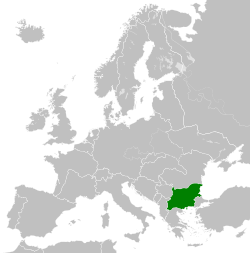

The Kingdom of Bulgaria in 1942. | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Sofia | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Bulgarian | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Bulgarian Orthodox | ||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Tsar (King) | |||||||||||||

• 1908–1918 | Ferdinand I | ||||||||||||

• 1918–1943 | Boris III | ||||||||||||

• 1943–1946 | Simeon II | ||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Council of Ministers | |||||||||||||

• 1908–1911 | Aleksandar Malinov (first) | ||||||||||||

• 1944–1946 | Kimon Georgiev (last) | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | World War I / World War II | ||||||||||||

| 22 September (o. s.) 1908 | |||||||||||||

| 1912–1913 | |||||||||||||

| 10 August 1913 | |||||||||||||

| 27 November 1919 | |||||||||||||

| 9 September 1944 | |||||||||||||

| 15 September 1946 | |||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 1908 | 95,223 km2 (36,766 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| 1946 | 160,994 km2 (62,160 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 1908 | 4,215,000 | ||||||||||||

• 1946 | 7,029,349 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Bulgarian lev | ||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | BG | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

The Kingdom of Bulgaria, also referred to as the Tsardom of Bulgaria and the Third Bulgarian Tsardom was a constitutional monarchy, which was established on 5 October (O.S. 22 September) 1908 when the Bulgarian state was raised from a principality to a kingdom. Ferdinand I was crowned a Tsar at the Declaration of Independence, mainly because of his military plans and for seeking options for unification of all Balkan lands with an ethnic Bulgarian majority (lands that had been seized from Bulgaria and given to the Ottoman Empire in the Treaty of Berlin).

The state was almost constantly at war throughout its existence, lending to its nickname as "the Balkan Prussia". For several years Bulgaria mobilized an army of more than 1 million people from its population of about 5 million and in the next decade (1910–20) it engaged in three wars – the First and Second Balkan Wars, and the First World War. Following the First World War the Bulgarian army was disbanded and forbidden to exist by the Allied powers, and all plans for national unification of the Bulgarian lands failed. Less than two decades later Bulgaria once again went to war for national unification as part of the Second World War, and once again found itself on the losing side, until it switched sides to the Allies in 1944. In 1946, the monarchy was abolished, its final Tsar was sent into exile and the Kingdom was replaced by the People's Republic of Bulgaria.

The Balkan Wars

Despite the establishment of a Bulgarian state in 1878, and the subsequent Bulgarian control over Eastern Rumelia in 1885 there was still a substantial Bulgarian population in the Balkans living under Ottoman rule, particularly in Macedonia. To complicate matters, Serbia and Greece too made claims over parts of Macedonia, while Serbia, as a Slavic nation, also considered Macedonian Slavs as belonging to the Serbian nation. Thus began a three-sided struggle for control of these areas which lasted until World War I. In 1903, there was a Bulgarian insurrection in Ottoman Macedonia and war seemed likely. In 1908, Ferdinand used the struggles among the Great Powers to declare Bulgaria an independent kingdom with himself as Tsar. He did this on 5 October (though celebrated on 22 September, as Bulgaria remained officially on the Julian Calendar until 1916) in the St Forty Martyrs Church in Veliko Tarnovo.

In 1911, the Nationalist Prime Minister Ivan Geshov set about forming an alliance with Greece and Serbia, and the three allies agreed to put aside their rivalries to plan a joint attack on the Ottomans.

In February 1912 a secret treaty was signed between Bulgaria and Serbia, and in May 1912 a similar treaty was signed with Greece. Montenegro was also brought into the pact. The treaties provided for the partition of Macedonia and Thrace between the allies, although the lines of partition were left dangerously vague. After the Ottomans refused to implement reforms in the disputed areas, the First Balkan War broke out in October 1912. (See Balkan Wars for details.)

The allies had an astonishing success. The Bulgarian army inflicted several crushing defeats on the Ottoman forces and advanced threateningly against Constantinople, while the Serbs and the Greeks took control of Macedonia. The Ottomans sued for peace in December. Negotiations broke down, and fighting resumed in February 1913. The Ottomans lost Adrianople to a Bulgarian task force. A second armistice followed in March, with the Ottomans losing all their European possessions west of the Midia-Enos line, not far from Istanbul. Bulgaria gained possession of most of Thrace, including Adrianople and the Aegean port of Dedeagach (today Alexandroupoli). Bulgaria also gained a slice of Macedonia, north and east of Thessaloniki, but only some small areas along her western borders.

Bulgaria sustained the heaviest casualties of any of the allies, and on this basis felt entitled to the largest share of the spoils. The Serbs in particular did not see things this way, and refused to vacate any of the territory they had seized in northern Macedonia (that is, the territory roughly corresponding to the modern Republic of Macedonia), stating that the Bulgarian army had failed to accomplish its pre-war goals at Adrianople (i. e., failing to capture it without Serbian help) and that the pre-war agreements on the division of Macedonia had to be revised. Some circles in Bulgaria inclined toward going to war with Serbia and Greece on this issue. In June 1913 Serbia and Greece formed a new alliance, against Bulgaria. The Serbian Prime Minister, Nikola Pasic, told Greece it could have Thrace if Greece helped Serbia keep Bulgaria out of Serbian part of Macedonia, and the Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos agreed. Seeing this as a violation of the pre-war agreements, and discreetly encouraged by Germany and Austria-Hungary, Tsar Ferdinand declared war on Serbia and Greece and the Bulgarian army attacked on June 29. The Serbian and the Greek forces were initially on the retreat on the western border, but they soon took the upper hand and forced Bulgaria into retreat. The fighting was very harsh, with many casualties, especially during the key Battle of Bregalnica. Soon Romania entered the war and attacked Bulgaria from the north. The Ottoman Empire also attacked from the south-east. The war was now definitely lost for Bulgaria, which had to abandon most of her claims of Macedonia to Serbia and Greece, while the revived Ottomans retook Adrianople. Romania took possession of southern Dobruja.

World War I

In the aftermath of the Balkan Wars, Bulgarian opinion turned against Russia and the western powers, whom the Bulgarians felt had done nothing to help them. The government of Vasil Radoslavov aligned Bulgaria with Germany and Austria-Hungary, even though this meant also becoming an ally of the Ottomans, Bulgaria's traditional enemy. But Bulgaria now had no claims against the Ottomans, whereas Serbia, Greece and Romania (allies of the UK and France) were all in possession of lands perceived in Bulgaria as Bulgarian. Bulgaria, recuperating from the Balkan Wars, sat out the first year of World War I, but when Germany promised to restore the boundaries of the Treaty of San Stefano, Bulgaria, which had the largest army in the Balkans, declared war on Serbia in October 1915. The UK, France, Italy and Russia then declared war on Bulgaria.

Bulgaria, in alliance with Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottomans, won military victories against Serbia and Romania, taking much of Macedonia (taking Skopje in October), advancing into Greek Macedonia, and taking Dobruja from the Romanians in September 1916. However, the war soon became unpopular with the majority of Bulgarian people, who suffered great economic hardship and also disliked fighting their fellow Orthodox Christians in alliance with the Muslim Ottomans. The Agrarian Party leader, Aleksandur Stamboliyski, was imprisoned for his opposition to the war. The Russian Revolution of February 1917 had a great effect in Bulgaria, spreading antiwar and anti-monarchist sentiment among the troops and in the cities. In June Radoslavov's government resigned. Mutinies broke out in the army, Stamboliyski was released and a republic was proclaimed.

The interwar years

In September 1918, the French, Serbs, British, Italians and Greeks broke through on the Macedonian front and Tsar Ferdinand was forced to sue for peace. Stamboliyski favoured democratic reforms, not a revolution. In order to head off the revolutionaries, he persuaded Ferdinand to abdicate in favour of his son Boris III. The revolutionaries were suppressed and the army disbanded. Under the Treaty of Neuilly (November 1919), Bulgaria lost its Aegean coastline to Greece and nearly all of its Macedonian territory to the new state of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and had to give Dobruja back to the Kingdom of Romania (see also Dobruja, Western Outlands, Western Thrace). Elections in March 1920 gave the Agrarians a large majority, and Stamboliyski formed Bulgaria's first genuinely democratic government.

Although it had not lost large amounts of territory, the nation had again struggled hard for nothing. The lost territories, especially the Dobroujea and Macedonia, were considered integral parts of Bulgaria and the pressure to retake them became an ultimately fatal obsession that drove the country into the arms of Nazi Germany. However, unlike the other defeated Eastern European state, Hungary, Bulgaria continued with essentially the same government as before.

Stamboliyski faced huge social problems in what was still a poor country, inhabited mostly by peasant smallholders. Bulgaria was saddled with huge war reparations to Yugoslavia and Romania, and had to deal with the problem of refugees as pro-Bulgarian Macedonians had to leave the Yugoslav Macedonia. Nevertheless, Stamboliyski was able to carry through many social reforms, although opposition from the Tsar, the landlords and the officers of the much-reduced but still influential army was powerful. Another bitter enemy was the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (VMRO), which favoured a war to regain Macedonia for Bulgaria. Faced with this array of enemies, Stamboliyski allied himself with the Bulgarian Communist Party and opened relations with the Soviet Union.

Interwar Bulgaria was highly backwards from an economic standpoint. Heavy industry was almost nonexistent due to a lack of major natural resources, and whatever manufacturing did exist consisted almost exclusively of textiles and handicrafts. Even these required extensive tariff protection to survive. Some natural resources did exist, but bad internal communications made it impossible to exploit them and nearly all important manufactured implements were imported. Farm machinery and chemical fertilizers were nearly unheard of. Agricultural products were almost the only thing Bulgaria could export and after 1929 it became very hard to do this.

Bulgaria was fortunate in lacking a native landowning class since historically the landowners had all been Turks displaced after independence in 1878. As such, Bulgarian agriculture was almost entirely one of small farmers and peasants. Plots were small and almost exclusively under 50 acres, but they were working intensively and even the tiniest 5-acre farms often produced crops for market sale. Bulgarian peasants also had a better work ethic than their counterparts in Romania or Hungary due to historical reasons. The Turkish landowners in olden times were often cruel and corrupt, but they also rarely bothered to visit their estates. And since they usually demanded payment from the peasants in the form of money or crops rather than labor, this created an added incentive to work hard that was lacking elsewhere in Eastern Europe.

As elsewhere in Eastern Europe, Bulgarian peasants traditionally grew grains for their landowners which after the war could not be effectively marketed due to competition from the United States and Western Europe. However, they were able to switch with little difficulty to garden crops and tobacco in contrast to other countries where the peasantry suffered harder due to continued reliance on corn and wheat.

While more successful than the rest of Eastern Europe, Bulgarian agriculture still suffered from the handicaps of backwards technology and especially rural overpopulation and scattered plots (due to the traditional practice of a peasant dividing his land equally among all surviving sons). And all agricultural exports were harmed by the onset of the Great Depression. On the other hand, an underdeveloped economy meant that Bulgaria had little trouble with debt and inflation. Just under half of industry was owned by foreign companies in contrast to the nearly 80% of Romanian industry.

Since the population was 85% ethnic Bulgarians, there was relatively little social strife aside from the conflict between the haves and have-nots. Most inhabitants of Sofia maintained close ties to the countryside, but this did not prevent a rift between the peasants and urban class (i.e. Sofia versus everyone else), although some was the result of deliberate manipulation by politicians seeking to take advantage of traditional peasant distrust of the "effeminate city slicker". Mostly however, it was due to a quarrel between the rulers and the ruled. Around 14% of the population were Muslims, mostly Turks (i.e. the remnant of the landowning class), but also a handful of so-called "Pomaks" (ethnic Bulgarians who practiced Islam). The Muslim population was alienated from the dominant Orthodox Christians both due to religious and historical reasons. They neither pressed for minority rights nor tried to set up their own schools, and instead asked nothing more than to be left alone to mind their own business. The Bulgarian government obliged except for a great willingness to assist them in emigrating back to Turkey.

By comparison to economics, Bulgaria's educational system was highly successful and less than half the population were illiterate. Eight years of schooling were required and over 80% of children attended. For the few special students who went past elementary school, the high schools were based on the German gymnasium. Competitive examinations were used to judge college applicants, and Bulgaria had a number of technical and specialized schools in addition to the University of Sofia. Many Bulgarian students also went abroad, primarily to Germany and Austria (educational ties with Russia ended in 1917). Overall, education reached more of the lower classes than anywhere else in Eastern Europe, but on the downside all too many students obtained degrees in the liberal arts and other abstract subjects and could not find work anywhere except in the government bureaucracy. Many of them gravitated towards the Bulgarian Communist Party.

The Bulgarian government had the same handicap as most constitutional monarchies, which was not drawing a clear line between what powers were granted to the king and what were granted to Parliament. The 1879 constitution was intended to put power in the hands of the latter, but still allowed a clever enough monarch to gain control of the machinery of government. Such was the case with the wily Tsar Ferdinand, who however had been forced to abdicate after the back-to-back losses of the Balkan Wars and World War I. His son Boris then succeeded him to the throne, but the young king could not replace the power his father had built through decades of intrigue. As such, Parliament came to dominate after Boris appointed Alexander Stamboliyski as prime minister. Stamboliyski's Agrarian Party soon dominated Parliament with over half the seats. The rest of the seats were taken by the Bulgarian Communist Party, which (interestingly enough) was the country's second largest political party and the only other one of any significance (there were a dozen or so minor parties, but they had no representation in Parliament or any real significance). The Agrarian Party chiefly represented peasants, and especially those who were disgruntled with the government in Sofia since Ferdinand's reign saw extensive corruption and theft of money from the peasantry. Also while most of the lower classes in Bulgaria supported annexation of Macedonia, they were disgruntled about the heavy bloodshed incurred in two unsuccessful wars to retake it. Indeed, Stamboliyski actually spent the war years in jail due to his vociferous criticism of it. As for the BCP, it was mainly staffed by intelligensia and urban professionals, but its chief constituents were the poorest peasants and other minorities. The AP by comparison represented better-off peasants. Under this climate, Stamboliyski hastily enacted a land reform in 1920, which was designed to break up some state properties, church lands, and the holdings of wealthier peasants. Predictably, it gave him widespread support and forced the BCP into an alliance with the AP mainly to gain a voice in Parliament.

However, Stamboliyski was a convinced anti-communist and sought to create an international movement to combat Marxism. This was his so-called "Green International", a counter to the communist "Red International". He traveled to Eastern European capitals promoting his view of a peasant alliance. But trouble began when he tried to spread it in Yugoslavia, a country that had very similar conditions to Bulgaria (i.e. very little industry and a large communist presence). Stamboliyski was well-liked in Belgrade because of supporting a peaceful solution to the Macedonia problem. He also advocated uniting all the Slavic-speaking nations in Eastern Europe into one large Yugoslav confederation. But he got into trouble because of the militant IMRO faction at home. Many Macedonian leaders had lived in Sofia since the failed 1903 revolt against the Ottoman Empire, and now they were joined by others who fled the Yugoslavian government (which maintained as its official position that Macedonians were ethnic Serbs). Since Bulgaria had been forced to limit the size of its armed forces after World War I, IMRO chieftains gained control of much of the border area with Yugoslavia.

In March 1923, Stamboliyski signed an agreement with Yugoslavia recognizing the new border and agreeing to suppress VMRO. This triggered a nationalist reaction, and on 9 June there was a coup organized by IMRO after the AP controlled 87% of Parliament in the elections that year. The Bulgarian government could only muster a handful of troops to resist, and even worse was a peasant mob with no guns rallied by Stamboliyski. Despite this, the streets of Sofia erupted in chaos and the hapless prime minister was lynched in addition to attacks on unarmed peasants. The whole affair seriously tarbrushed Bulgaria's international image. A right wing government under Aleksandar Tsankov took power, backed by the Tsar, the army and the VMRO, who waged a White terror against the Agrarians and the Communists. The Communist leader Georgi Dimitrov fled to the Soviet Union. There was savage repression in 1925 following the second of two failed attempts on the Tsar's life in the bomb attack on Sofia Cathedral (the first attempt took place in the mountain pass of Arabakonak). But in 1926 the Tsar persuaded Tsankov to resign and a more moderate government under Andrey Lyapchev took office. An amnesty was proclaimed, although the Communists remained banned. The Agrarians reorganised and won elections in 1931 under the leadership of Nikola Mushanov.

Just when political stability had been restored, the full effects of the Great Depression hit Bulgaria, and social tensions rose again. In May 1934 there was another coup, the Agrarians were again suppressed, and an authoritarian regime headed by Kimon Georgiev established with the backing of Tsar Boris. In April 1935 Boris took power himself, ruling through puppet Prime Ministers Georgi Kyoseivanov (1935–40) and Bogdan Filov (1940–43). The Tsar's regime banned all opposition parties and took Bulgaria into alliance with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Although the signing of the Balkan Pact of 1938 restored good relations with Yugoslavia and Greece, the territorial issue continued to simmer.

World War II

Faced by an invasion, Bulgaria drifted into World War II under Filov's government. On 7 September 1940, Bulgaria was bribed by the return of southern Dobruja from the Kingdom of Romania. This was done on the orders of German dictator Adolf Hitler and implemented by the Treaty of Craiova.

On 1 March 1941, Bulgaria formally signed the Tripartite Pact, becoming an ally of Nazi Germany, the Empire of Japan, and the Kingdom of Italy. German troops entered the country in preparation for the German invasions of the Kingdom of Greece and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. When Yugoslavia and Greece were defeated, Bulgaria was allowed to occupy all of Greek Thrace and most of Macedonia. Bulgaria declared war on Britain and the United States, but resisted German pressure to declare war on the Soviet Union, fearful of pro-Russian sentiment in the country.

In August 1943 Tsar Boris died suddenly after returning from Germany (possibly assassinated, although this has never been proved) and was succeeded by his six-year-old son Simeon II. Power was held by a council of regents headed by the young Tsar's uncle, Prince Kirill. The new Prime Minister, Dobri Bozhilov, was in most respects a German puppet.

Resistance to the Germans and the Bulgarian regime was widespread by 1943, co-ordinated mainly by the Communists. Together with the Agrarians, now led by Nikola Petkov, the Social Democrats and even with many army officers they founded the Fatherland Front. Partisans operated in the mountainous west and south. By 1944 it was obvious that Germany was losing the war and the regime began to look for a way out. Bozhilov resigned in May, and his successor Ivan Ivanov Bagryanov tried to arrange negotiations with the western Allies.

Meanwhile, the capital Sofia was bombed by Allied aircraft in late 1943 and early 1944, with raids on other major cities following later. But it was the Soviet army which was rapidly advancing towards Bulgaria. In August Bulgaria unilaterally announced its withdrawal from the war and asked the German troops to leave: Bulgarian troops were hastily withdrawn from Greece and Yugoslavia. In September the Soviets crossed the northern border. The government, desperate to avoid a Soviet occupation, declared war on Germany, but the Soviets could not be put off, and on September 8 they declared war on Bulgaria – which thus found itself for a few days at war with both Germany and the Soviet Union. On September 16, the Soviet army entered Sofia.

Communist coup

The Fatherland Front took office in Sofia following a coup d'état, setting up a broad coalition under the former ruler Kimon Georgiev and including the Social Democrats and the Agrarians. Under the terms of the peace settlement, Bulgaria was allowed to keep Southern Dobruja, but formally renounced all claims to Greek and Yugoslav territory. 150,000 Bulgarians were expelled from Greek Thrace. The Communists deliberately took a minor role in the new government at first, but the Soviet representatives were the real power in the country. A Communist-controlled People's Militia was set up, which harassed and intimidated non-Communist parties.

On 1 February 1945, the new realities of power in Bulgaria were shown when Regent Prince Kiril, former Prime Minister Bogdan Filov, and hundreds of other officials of the old regime were arrested on charges of war crimes. By June, Kirill and the other Regents, twenty-two former ministers, and many others had been executed. In September 1946, the monarchy was abolished by plebiscite, and young Tsar Simeon was sent into exile. The Communists now openly took power, with Vasil Kolarov becoming President and Dimitrov becoming Prime Minister. Free elections promised for 1946 were blatantly rigged and were boycotted by the opposition. The Agrarians refused to co-operate with the new regime, and in June 1947 their leader Nikola Petkov was arrested. Despite strong international protests he was executed in September. This marked the final establishment of a Communist regime in Bulgaria.

See also

- Ferdinand I of Bulgaria

- Boris III of Bulgaria

- Balkan Wars

- History of Bulgaria

- History of Bulgaria (1878–1946)

Footnotes

External links

- Rulers of Bulgaria at World Statesmen