List of interstellar and circumstellar molecules

This is a list of molecules that have been detected in the interstellar medium and circumstellar envelopes, grouped by the number of component atoms. The chemical formula is listed for each detected compound, along with any ionized form that has also been observed.

Detection

The molecules listed below were detected by spectroscopy. Their spectral features are generated by transitions of component electrons between different energy levels, or by rotational or vibrational spectra. Detection usually occurs in radio, microwave, or infrared portions of the spectrum.[1]

Interstellar molecules are formed by chemical reactions within very sparse interstellar or circumstellar clouds of dust and gas. Usually this occurs when a molecule becomes ionized, often as the result of an interaction with a cosmic ray. This positively charged molecule then draws in a nearby reactant by electrostatic attraction of the neutral molecule's electrons. Molecules can also be generated by reactions between neutral atoms and molecules, although this process is generally slower.[2] The dust plays a critical role of shielding the molecules from the ionizing effect of ultraviolet radiation emitted by stars.[3]

History

The chemistry of life may have begun shortly after the Big Bang, 13.8 billion years ago, during a habitable epoch when the Universe was only 10–17 million years old.[4][5]

The first carbon-containing molecule detected in the interstellar medium was the methylidyne radical (CH) in 1937.[6] From the early 1970s it was becoming evident that interstellar dust consisted of a large component of more complex organic molecules (COMs),[7] probably polymers. Chandra Wickramasinghe proposed the existence of polymeric composition based on the molecule formaldehyde (H2CO).[8] Fred Hoyle and Chandra Wickramasinghe later proposed the identification of bicyclic aromatic compounds from an analysis of the ultraviolet extinction absorption at 2175 Å,[9] thus demonstrating the existence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon molecules in space.

In 2004, scientists reported[10] detecting the spectral signatures of anthracene and pyrene in the ultraviolet light emitted by the Red Rectangle nebula (no other such complex molecules had ever been found before in outer space). This discovery was considered a confirmation of a hypothesis that as nebulae of the same type as the Red Rectangle approach the ends of their lives, convection currents cause carbon and hydrogen in the nebulae's core to get caught in stellar winds, and radiate outward.[11] As they cool, the atoms supposedly bond to each other in various ways and eventually form particles of a million or more atoms. The scientists inferred[10] that since they discovered polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) — which may have been vital in the formation of early life on Earth — in a nebula, by necessity they must originate in nebulae.[11]

In 2010, fullerenes (or "buckyballs") were detected in nebulae.[12] Fullerenes have been implicated in the origin of life; according to astronomer Letizia Stanghellini, "It's possible that buckyballs from outer space provided seeds for life on Earth."[13]

In October 2011, scientists found using spectroscopy that cosmic dust contains complex organic compounds ("amorphous organic solids with a mixed aromatic-aliphatic structure") that could be created naturally, and rapidly, by stars.[14][15][16] The compounds are so complex that their chemical structures resemble the makeup of coal and petroleum; such chemical complexity was previously thought to arise only from living organisms.[14] These observations suggest that organic compounds introduced on Earth by interstellar dust particles could serve as basic ingredients for life due to their surface-catalytic activities.[17][18] One of the scientists suggested that these compounds may have been related to the development of life on Earth and said that, "If this is the case, life on Earth may have had an easier time getting started as these organics can serve as basic ingredients for life."[14]

In August 2012, astronomers at Copenhagen University reported the detection of a specific sugar molecule, glycolaldehyde, in a distant star system. The molecule was found around the protostellar binary IRAS 16293-2422, which is located 400 light years from Earth.[19][20] Glycolaldehyde is needed to form ribonucleic acid, or RNA, which is similar in function to DNA. This finding suggests that complex organic molecules may form in stellar systems prior to the formation of planets, eventually arriving on young planets early in their formation.[21]

In September 2012, NASA scientists reported that PAHs, subjected to interstellar medium (ISM) conditions, are transformed, through hydrogenation, oxygenation, and hydroxylation, to more complex organics — "a step along the path toward amino acids and nucleotides, the raw materials of proteins and DNA, respectively".[22][23] Further, as a result of these transformations, the PAHs lose their spectroscopic signature which could be one of the reasons "for the lack of PAH detection in interstellar ice grains, particularly the outer regions of cold, dense clouds or the upper molecular layers of protoplanetary disks."[22][23]

PAHs are found everywhere in deep space[24] and, in June 2013, PAHs were detected in the upper atmosphere of Titan, the largest moon of the planet Saturn.[25]

In 2013, Dwayne Heard at the University of Leeds suggested[26] that quantum mechanical tunneling could explain a reaction his group observed taking place, at a significantly higher than expected rate, between cold (around 63 Kelvin) hydroxyl and methanol molecules, apparently bypassing intramolecular energy barriers which would have to be overcome by thermal energy or ionization events for the same rate to exist at warmer temperatures. The proposed tunneling mechanism may help explain the common observation of fairly complex molecules (up to tens of atoms) in interstellar space.

A particularly large and rich region for detecting interstellar molecules is Sagittarius B2 (Sgr B2). This giant molecular cloud lies near the center of the Milky Way galaxy and is a frequent target for new searches. About half of the molecules listed below were first found near Sgr B2, and nearly every other molecule has since been detected in this feature.[27] A rich source of investigation for circumstellar molecules is the relatively nearby star CW Leonis (IRC +10216), where about 50 compounds have been identified.[28]

In March 2015, NASA scientists reported that, for the first time, complex DNA and RNA organic compounds of life, including uracil, cytosine and thymine, have been formed in the laboratory under outer space conditions, using starting chemicals, such as pyrimidine, found in meteorites. Pyrimidine, like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), the most carbon-rich chemical found in the Universe, may have been formed in red giants or in interstellar dust and gas clouds, according to the scientists.[29]

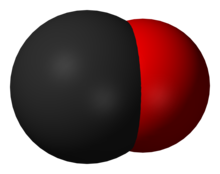

In October 2016, astronomers reported that the very basic chemical ingredients of life—the carbon-hydrogen molecule (CH, or methylidyne radical), the carbon-hydrogen positive ion (CH+) and the carbon ion (C+)—are the result, in large part, of ultraviolet light from stars, rather than in other ways, such as the result of turbulent events related to supernovae and young stars, as thought earlier.[30][31]

Theoretical models

To explain the observed ratios of isomeric compounds, the minimum energy principle has been used. In the majority of cases, it explains that some organic entities have greater abundance than their isomers due to the lower total energies of the first one. However, a few exceptions where the principle fails are also known.[32]

Another approach ignores energy and deals only with the molecular complexity estimated by the information entropy index. It speculates that the points of several natural compounds (urea, pyrimidine, dihydroxyacetone, uracil, cytosine, glycine, and alanine) fall into the range of the values typical for the known interstellar molecules that indicates high probability of their detection in interstellar environment. Additionally the molecules with maximal information entropy, i.e. the most complex compounds, make up approximately a half of the interstellar set and their percentage is decreased with the size. This trend may be associated with the different stabilities of the molecules with uniform (usually more stable) and diversified (usually less stable) chemical structures, so the detectable molecules with a large size must possess symmetric structure more probably than non-symmetric. The remarkable detection of low-entropy (highly symmetric) fullerene molecules supports this assumption. It is also noted that information entropy reflects the depth of hydrogenation of interstellar entities: the molecules with maximal information entropy are hydrogen-poor whereas the others are mainly hydrogen-rich.[33]

Molecules

The following tables list molecules that have been detected in the interstellar medium, grouped by the number of component atoms. If there is no entry in the molecule column, only the ionized form has been detected. For molecules where no designation was given in the scientific literature, that field is left empty. Mass is given in atomic mass units. The total number of unique species, including distinct ionization states, is listed in parentheses in each section header.

Most of the molecules detected so far are organic. Only one inorganic species has been observed in molecules which contain at least five atoms, SiH4.[34] Larger molecules have so far all had at least one carbon atom, with no N−N or O−O bonds.[34]

Diatomic (43)

3 cation is one of the most abundant ions in the universe. It was first detected in 1993.[73][74]

Triatomic (43)

Four atoms (27)

| Molecule | Designation | Mass | Ions |

|---|---|---|---|

| CH3 | Methyl radical[105] | 15 | — |

| l-C3H | Propynylidyne[36][106] | 37 | l-C3H+[107] |

| c-C3H | Cyclopropynylidyne[108] | 37 | — |

| C3N | Cyanoethynyl[109] | 50 | C3N−[110] |

| C3O | Tricarbon monoxide[106] | 52 | — |

| C3S | Tricarbon sulfide[36][78] | 68 | — |

| — | Hydronium | 19 | H3O+[111] |

| C2H2 | Acetylene[112] | 26 | — |

| H2CN | Methylene amidogen[113] | 28 | H2CN+[46] |

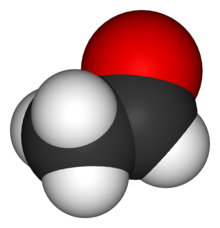

| H2CO | Formaldehyde[104] | 30 | — |

| H2CS | Thioformaldehyde[114] | 46 | — |

| HCCN | —[115] | 39 | — |

| HCCO | Ketenyl[116] | 41 | — |

| — | Protonated hydrogen cyanide | 28 | HCNH+[90] |

| — | Protonated carbon dioxide | 45 | HOCO+[117] |

| HCNO | Fulminic acid[118] | 43 | — |

| HOCN | Cyanic acid[119] | 43 | — |

| HOOH | Hydrogen peroxide[120] | 34 | — |

| HNCO | Isocyanic acid[100] | 43 | — |

| HNCS | Isothiocyanic acid[121] | 59 | — |

| NH3 | Ammonia[36][122] | 17 | — |

| HSCN | Thiocyanic acid[123] | 59 | — |

| SiC3 | Silicon tricarbide[36] | 64 | — |

| HMgNC | Hydromagnesium isocyanide[124] | 51.3 | — |

Five atoms (19)

| Molecule | Designation | Mass | Ions |

|---|---|---|---|

| — | Ammonium ion[126][127] | 18 | NH+ 4 |

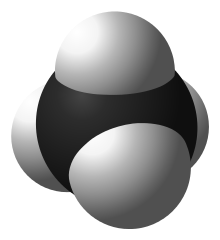

| CH4 | Methane[128] | 16 | — |

| CH3O | Methoxy radical[129] | 31 | — |

| c-C3H2 | Cyclopropenylidene[47][130][131] | 38 | — |

| l-H2C3 | Propadienylidene[131] | 38 | — |

| H2CCN | Cyanomethyl[132] | 40 | — |

| H2C2O | Ketene[100] | 42 | — |

| H2CNH | Methylenimine[133] | 29 | — |

| HNCNH | Carbodiimide[134] | 42 | — |

| — | Protonated formaldehyde | 31 | H2COH+[135] |

| C4H | Butadiynyl[36] | 49 | C4H−[136] |

| HC3N | Cyanoacetylene[36][47][90][137][138] | 51 | — |

| HCC-NC | Isocyanoacetylene[139] | 51 | — |

| HCOOH | Formic acid[140][137] | 46 | — |

| NH2CN | Cyanamide[141] | 42 | — |

| — | Protonated cyanogen | 53 | NCCNH+[142] |

| HC(O)CN | Cyanoformaldehyde[143] | 55 | — |

| SiC4 | Silicon-carbide cluster[71] | 92 | — |

| SiH4 | Silane[144] | 32 | — |

Six atoms (16)

| Molecule | Designation | Mass | Ions |

|---|---|---|---|

| c-H2C3O | Cyclopropenone[146] | 54 | — |

| E-HNCHCN | E-Cyanomethanimine[147] | 54 | — |

| C2H4 | Ethylene[148] | 28 | — |

| CH3CN | Acetonitrile[100][149][150] | 40 | — |

| CH3NC | Methyl isocyanide[149] | 40 | — |

| CH3OH | Methanol[100][151] | 32 | — |

| CH3SH | Methanethiol[152] | 48 | — |

| l-H2C4 | Diacetylene[36][153] | 50 | — |

| — | Protonated cyanoacetylene | 52 | HC3NH+[90] |

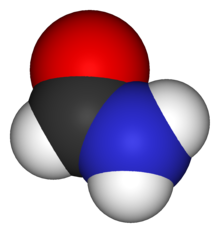

| HCONH2 | Formamide[145] | 44 | — |

| C5H | Pentynylidyne[36][78] | 61 | — |

| C5N | Cyanobutadiynyl radical[154] | 74 | — |

| HC2CHO | Propynal[155] | 54 | — |

| HC4N | —[36] | 63 | — |

| CH2CNH | Ketenimine[130] | 40 | — |

| C5S | —[156] | 92 | — |

Seven atoms (10)

| Molecule | Designation | Mass | Ions |

|---|---|---|---|

| c-C2H4O | Ethylene oxide[158] | 44 | — |

| CH3C2H | Methylacetylene[47] | 40 | — |

| H3CNH2 | Methylamine[159] | 31 | — |

| CH2CHCN | Acrylonitrile[100][149] | 53 | — |

| H2CHCOH | Vinyl alcohol[157] | 44 | — |

| C6H | Hexatriynyl radical[36][78] | 73 | C6H−[131][160] |

| HC4CN | Cyanodiacetylene[100][138][149] | 75 | — |

| CH3CHO | Acetaldehyde[36][158] | 44 | — |

| CH3NCO | Methyl isocyanate[161] | 57 | — |

Eight atoms (11)

| Molecule | Designation | Mass |

|---|---|---|

| H3CC2CN | Methylcyanoacetylene[163] | 65 |

| H2COHCHO | Glycolaldehyde[164] | 60 |

| HCOOCH3 | Methyl formate[100][137][164] | 60 |

| CH3COOH | Acetic acid[162] | 60 |

| H2C6 | Hexapentaenylidene[36][153] | 74 |

| CH2CHCHO | Propenal[130] | 56 |

| CH2CCHCN | Cyanoallene[130][163] | 65 |

| CH3CHNH | Ethanimine[165] | 43 |

| C7H | Heptatrienyl radical[166] | 85 |

| NH2CH2CN | Aminoacetonitrile[167] | 56 |

| (NH2)2CO | Urea[168] | 60 |

Nine atoms (10)

| Molecule | Designation | Mass | Ions |

|---|---|---|---|

| CH3C4H | Methyldiacetylene[169] | 64 | — |

| CH3OCH3 | Dimethyl Ether[170] | 46 | — |

| CH3CH2CN | Propionitrile[36][100][149] | 55 | — |

| CH3CONH2 | Acetamide[130][145] | 59 | — |

| CH3CH2OH | Ethanol[171] | 46 | — |

| C8H | Octatetraynyl radical[172] | 97 | C8H−[173][174] |

| HC7N | Cyanohexatriyne or Cyanotriacetylene[36][122][175][176] | 99 | — |

| CH3CHCH2 | Propylene (propene)[177] | 42 | — |

| CH3CH2SH | Ethyl mercaptan[178] | 62 | — |

Ten or more atoms (15)

| Atoms | Molecule | Designation | Mass | Ions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | (CH3)2CO | Acetone[100][179] | 58 | — |

| 10 | (CH2OH)2 | Ethylene glycol[180][181] | 62 | — |

| 10 | CH3CH2CHO | Propanal[130] | 58 | — |

| 10 | CH3C5N | Methyl-cyano-diacetylene[130] | 89 | — |

| 10 | CH3CHCH2O | Propylene oxide[182] | 58 | — |

| 11 | HC8CN | Cyanotetra-acetylene[36][175] | 123 | — |

| 11 | C2H5OCHO | Ethyl formate[183] | 74 | — |

| 11 | CH3COOCH3 | Methyl acetate[184] | 74 | — |

| 11 | CH3C6H | Methyltriacetylene[130][169] | 88 | — |

| 12 | C6H6 | Benzene[153] | 78 | — |

| 12 | C3H7CN | n-Propyl cyanide[183] | 69 | — |

| 12 | (CH3)2CHCN | iso-Propyl cyanide[185][186] | 69 | — |

| 13 | HC10CN | Cyanodecapentayne[175] | 147 | — |

| 13 | HC11N | Cyanopentaacetylene[175] | 159 | — |

| 60 | C60 | Buckminsterfullerene (C60 fullerene)[187] |

720 | C+ 60[188][189] |

| 70 | C70 | C70 fullerene[187] | 840 | — |

Deuterated molecules (20)

These molecules all contain one or more deuterium atoms, a heavier isotope of hydrogen.

| Atoms | Molecule | Designation |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | HD | Hydrogen deuteride[190][191] |

| 3 | H2D+, HD+ 2 |

Trihydrogen cation[190][191] |

| 3 | HDO, D2O | Heavy water[192][193] |

| 3 | DCN | Hydrogen cyanide[194] |

| 3 | DCO | Formyl radical[194] |

| 3 | DNC | Hydrogen isocyanide[194] |

| 3 | N2D+ | —[194] |

| 4 | NH2D, NHD2, ND3 | Ammonia[191][195][196] |

| 4 | HDCO, D2CO | Formaldehyde[191][197] |

| 4 | DNCO | Isocyanic acid[198] |

| 5 | NH3D+ | Ammonium ion[199][200] |

| 6 | NH 2CDO; NHDCHO |

Formamide[198] |

| 7 | CH2DCCH, CH3CCD | Methylacetylene[201][202] |

Unconfirmed (13)

Evidence for the existence of the following molecules has been reported in scientific literature, but the detections are either described as tentative by the authors, or have been challenged by other researchers. They await independent confirmation.

| Atoms | Molecule | Designation |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | SiH | Silylidine[88] |

| 4 | PH3 | Phosphine[203] |

| 4 | MgCCH | Magnesium monoacetylide[156] |

| 4 | NCCP | Cyanophosphaethyne[156] |

| 5 | C5 | Linear C5[43] |

| 5 | H2NCO+ | —[204] |

| 4 | SiH3CN | Silyl cyanide[156] |

| 10 | H2NH2CCOOH | Glycine[205][206] |

| 12 | CO(CH2OH)2 | Dihydroxyacetone[207] |

| 12 | C2H5OCH3 | Ethyl methyl ether[208] |

| 18 | C 10H+ 8 |

Naphthalene cation[209] |

| 24 | C24 | Graphene[210] |

| 24 | C14H10 | Anthracene[10][211] |

| 26 | C16H10 | Pyrene[10] |

See also

- Abiogenesis

- Astrobiology

- Astrochemistry

- Atomic and molecular astrophysics

- Cosmic dust

- Cosmic ray

- Cosmochemistry

- Diffuse interstellar band

- Extraterrestrial liquid water

- Forbidden mechanism

- Intergalactic dust

- Interplanetary medium

- Interstellar medium

- Organic compound

- Outer space

- Panspermia

- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH)

- Spectroscopy

References

- ^ Shu, Frank H. (1982), The Physical Universe: An Introduction to Astronomy, University Science Books, ISBN 0-935702-05-9

- ^ Dalgarno, A. (2006), "Interstellar Chemistry Special Feature: The galactic cosmic ray ionization rate", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103 (33): 12269–12273, Bibcode:2006PNAS..10312269D, doi:10.1073/pnas.0602117103, PMC 1567869, PMID 16894166

- ^ Brown, Laurie M.; Pais, Abraham; Pippard, A. B. (1995), "The physics of the interstellar medium", Twentieth Century Physics (2nd ed.), CRC Press, p. 1765, ISBN 0-7503-0310-7

- ^ Loeb, Abraham (October 2014). "The Habitable Epoch of the Early Universe". International Journal of Astrobiology. 13 (4): 337–339. arXiv:1312.0613. Bibcode:2014IJAsB..13..337L. doi:10.1017/S1473550414000196. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ Dreifus, Claudia (2 December 2014). "Much-Discussed Views That Go Way Back - Avi Loeb Ponders the Early Universe, Nature and Life". New York Times. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ Woon, D. E. (May 2005), Methylidyne radical, The Astrochemist, retrieved 2007-02-13

- ^ Ruaud, M.; Loison, J.C.; Hickson, K.M.; Gratier, P.; Hersant, F.; Wakelam, V. (2015). "Modeling Complex Organic Molecules in dense regions: Eley-Rideal and complex induced reaction". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 447 (4): 4004–4017. arXiv:1412.6256. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.447.4004R. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu2709.

- ^ N.C. Wickramasinghe, Formaldehyde Polymers in Interstellar Space, Nature, 252, 462, 1974

- ^ F. Hoyle and N.C. Wickramasinghe, Identification of the lambda 2200Å interstellar absorption feature, Nature, 270, 323, 1977

- ^ a b c d Battersby, S. (2004). "Space molecules point to organic origins". New Scientist. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- ^ a b Mulas, G.; Malloci, G.; Joblin, C.; Toublanc, D. (2006). "Estimated IR and phosphorescence emission fluxes for specific polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the Red Rectangle". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 446 (2): 537–549. arXiv:astro-ph/0509586. Bibcode:2006A&A...446..537M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053738.

- ^ García-Hernández, D. A.; Manchado, A.; García-Lario, P.; Stanghellini, L.; Villaver, E.; Shaw, R. A.; Szczerba, R.; Perea-Calderón, J. V. (2010-10-28). "Formation Of Fullerenes In H-Containing Planatary Nebulae". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 724 (1): L39–L43. arXiv:1009.4357. Bibcode:2010ApJ...724L..39G. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/724/1/L39.

- ^ Atkinson, Nancy (2010-10-27). "Buckyballs Could Be Plentiful in the Universe". Universe Today. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ^ a b c Chow, Denise (26 October 2011). "Discovery: Cosmic Dust Contains Organic Matter from Stars". Space.com. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- ^ ScienceDaily Staff (26 October 2011). "Astronomers Discover Complex Organic Matter Exists Throughout the Universe". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ Kwok, Sun; Zhang, Yong (26 October 2011). "Mixed aromatic–aliphatic organic nanoparticles as carriers of unidentified infrared emission features". Nature. 479 (7371): 80–3. Bibcode:2011Natur.479...80K. doi:10.1038/nature10542. PMID 22031328.

- ^ Gallori, Enzo (November 2010). "Astrochemistry and the origin of genetic material". Rendiconti Lincei. 22 (2): 113–118. doi:10.1007/s12210-011-0118-4. Retrieved 2011-08-11.

- ^ Martins, Zita (February 2011). "Organic Chemistry of Carbonaceous Meteorites". Elements. 7 (1): 35–40. doi:10.2113/gselements.7.1.35. Retrieved 2011-08-11.

- ^ Than, Ker (August 29, 2012). "Sugar Found In Space". National Geographic. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- ^ Staff (August 29, 2012). "Sweet! Astronomers spot sugar molecule near star". AP News. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- ^ Jørgensen, J. K.; Favre, C.; Bisschop, S.; Bourke, T.; Dishoeck, E.; Schmalzl, M. (2012). "Detection of the simplest sugar, glycolaldehyde, in a solar-type protostar with ALMA" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal Letters. eprint. 757: L4. arXiv:1208.5498. Bibcode:2012ApJ...757L...4J. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/757/1/L4.

- ^ a b Staff (September 20, 2012). "NASA Cooks Up Icy Organics to Mimic Life's Origins". Space.com. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Gudipati, Murthy S.; Yang, Rui (September 1, 2012). "In-Situ Probing Of Radiation-Induced Processing Of Organics In Astrophysical Ice Analogs—Novel Laser Desorption Laser Ionization Time-Of-Flight Mass Spectroscopic Studies". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 756 (1): L24. Bibcode:2012ApJ...756L..24G. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/756/1/L24. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ Clavin, Whitney (10 February 2015). "Why Comets Are Like Deep Fried Ice Cream". NASA. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ López-Puertas, Manuel (June 6, 2013). "PAH's in Titan's Upper Atmosphere". CSIC. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/351444/description/Interstellar_chemistry_makes_use_of_quantum_shortcut#comment_351468

- ^ Cummins, S. E.; Linke, R. A.; Thaddeus, P. (1986), "A survey of the millimeter-wave spectrum of Sagittarius B2", Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 60: 819–878, Bibcode:1986ApJS...60..819C, doi:10.1086/191102

- ^ Kaler, James B. (2002), The hundred greatest stars, Copernicus Series, Springer, ISBN 0-387-95436-8, retrieved 2011-05-09

- ^ Marlaire, Ruth (3 March 2015). "NASA Ames Reproduces the Building Blocks of Life in Laboratory". NASA. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ a b Landau, Elizabeth (12 October 2016). "Building Blocks of Life's Building Blocks Come From Starlight". NASA. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Morris, Patrick W.; Gupta, Harshal; Nagy, Zsofia; Pearson, John C.; Ossenkopf-Okada, Volker; Falgarone, Edith; Lis, Dariusz C.; Gerin, Maryvonne; Melnick, Gary; Neufeld, David A.; Bergin, Edwin A. (2016). "Herschel/HIFI Spectral Mapping of C+, CH+, and CH in Orion BN/Kl: The Prevailing Role of Ultraviolet Irradiation in CH+ Formation". The Astrophysical Journal. 829: 15. Bibcode:2016ApJ...829...15M. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/829/1/15.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Lattelais, M.; Pauzat, F.; Ellinger, Y.; Ceccarelli, C. (2009). "INTERSTELLAR COMPLEX ORGANIC MOLECULES AND THE MINIMUM ENERGY PRINCIPLE". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 696. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/696/2/L133.

- ^ Sabirov, Denis (1 December 2016). "Information entropy of interstellar and circumstellar carbon-containing molecules: Molecular size against structural complexity". Computational and Theoretical Chemistry. 1097 (1): 83–91. doi:10.1016/j.comptc.2016.10.014.

- ^ a b Klemperer, William (2011), "Astronomical Chemistry", Annual Review of Physical Chemistry, 62: 173–184, doi:10.1146/annurev-physchem-032210-103332

- ^ The Structure of Molecular Cloud Cores, Centre for Astrophysics and Planetary Science, University of Kent, retrieved 2007-02-16

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Ziurys, Lucy M. (2006), "The chemistry in circumstellar envelopes of evolved stars: Following the origin of the elements to the origin of life", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103 (33): 12274–12279, Bibcode:2006PNAS..10312274Z, doi:10.1073/pnas.0602277103, PMC 1567870, PMID 16894164

- ^ a b c Cernicharo, J.; Guelin, M. (1987), "Metals in IRC+10216 - Detection of NaCl, AlCl, and KCl, and tentative detection of AlF", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 183 (1): L10–L12, Bibcode:1987A&A...183L..10C

- ^ Ziurys, L. M.; Apponi, A. J.; Phillips, T. G. (1994), "Exotic fluoride molecules in IRC +10216: Confirmation of AlF and searches for MgF and CaF", Astrophysical Journal, 433 (2): 729–732, Bibcode:1994ApJ...433..729Z, doi:10.1086/174682

- ^ Tenenbaum, E. D.; Ziurys, L. M. (2009), "Millimeter Detection of AlO (X2Σ+): Metal Oxide Chemistry in the Envelope of VY Canis Majoris", Astrophysical Journal, 694: L59–L63, Bibcode:2009ApJ...694L..59T, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/694/1/L59

- ^ Barlow, M. J.; Swinyard, B. M.; Owen, P. J.; Cernicharo, J.; Gomez, H. L.; Ivison, R. J.; Lim, T. L.; Matsuura, M.; Miller, S.; Olofsson, G.; Polehampton, E. T. (2013), "Detection of a Noble Gas Molecular Ion, 36ArH+, in the Crab Nebula", Science, 342 (6164): 1343–1345, doi:10.1126/science.124358213

- ^ Quenqua, Douglas (13 December 2013). "Noble Molecules Found in Space". New York Times. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ Lambert, D. L.; Sheffer, Y.; Federman, S. R. (1995), "Hubble Space Telescope observations of C2 molecules in diffuse interstellar clouds", Astrophysical Journal, 438: 740–749, Bibcode:1995ApJ...438..740L, doi:10.1086/175119

- ^ a b c Galazutdinov, G. A.; Musaev, F. A.; Krelowski, J. (2001), "On the detection of the linear C5 molecule in the interstellar medium", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 325 (4): 1332–1334, Bibcode:2001MNRAS.325.1332G, doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2001.04388.x

- ^ Neufeld, D. A.; et al. (2006), "Discovery of interstellar CF+", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 454 (2): L37–L40, arXiv:astro-ph/0603201, Bibcode:2006A&A...454L..37N, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200600015

- ^ a b Adams, Walter S. (1941), "Some Results with the COUDÉ Spectrograph of the Mount Wilson Observatory", Astrophysical Journal, 93: 11–23, Bibcode:1941ApJ....93...11A, doi:10.1086/144237

- ^ a b c d e f Smith, D. (1988), "Formation and Destruction of Molecular Ions in Interstellar Clouds", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 324 (1578): 257–273, Bibcode:1988RSPTA.324..257S, doi:10.1098/rsta.1988.0016

- ^ a b c d e f g Fuente, A.; et al. (2005), "Photon-dominated Chemistry in the Nucleus of M82: Widespread HOC+ Emission in the Inner 650 Parsec Disk", Astrophysical Journal, 619 (2): L155–L158, arXiv:astro-ph/0412361, Bibcode:2005ApJ...619L.155F, doi:10.1086/427990

- ^ a b Guelin, M.; Cernicharo, J.; Paubert, G.; Turner, B. E. (1990), "Free CP in IRC + 10216", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 230: L9–L11, Bibcode:1990A&A...230L...9G

- ^ a b c Dopita, Michael A.; Sutherland, Ralph S. (2003), Astrophysics of the diffuse universe, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-43362-7

- ^ Agúndez, M.; et al. (2010-07-30), "Astronomical identification of CN−, the smallest observed molecular anion", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 517: L2, arXiv:1007.0662, Bibcode:2010A&A...517L...2A, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201015186, retrieved 2010-09-03

- ^ Khan, Amina. "Did two planets around nearby star collide? Toxic gas holds hints". LA Times. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ^ "Molecular Gas Clumps from the Destruction of Icy Bodies in the β Pictoris Debris Disk". Science. 343: 1490–1492. March 6, 2014. arXiv:1404.1380. Bibcode:2014Sci...343.1490D. doi:10.1126/science.1248726. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Latter, W. B.; Walker, C. K.; Maloney, P. R. (1993), "Detection of the Carbon Monoxide Ion (CO+) in the Interstellar Medium and a Planetary Nebula", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 419: L97, Bibcode:1993ApJ...419L..97L, doi:10.1086/187146

- ^ Furuya, R. S.; et al. (2003), "Interferometric observations of FeO towards Sagittarius B2", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 409 (2): L21–L24, Bibcode:2003A&A...409L..21F, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20031304

- ^ Adams, Walter S. (1970), "Rocket Observation of Interstellar Molecular Hydrogen", Astrophysical Journal, 161: L81–L85, Bibcode:1970ApJ...161L..81C, doi:10.1086/180575

- ^ Blake, G. A.; Keene, J.; Phillips, T. G. (1985), "Chlorine in dense interstellar clouds - The abundance of HCl in OMC-1", Astrophysical Journal, Part 1, 295: 501–506, Bibcode:1985ApJ...295..501B, doi:10.1086/163394

- ^ De Luca, M.; Gupta, H.; Neufeld, D.; Gerin, M.; Teyssier, D.; Drouin, B. J.; Pearson, J. C.; Lis, D. C.; Monje, R. (2012), "Herschel/HIFI Discovery of HCl+ in the Interstellar Medium", The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 751 (2): L37, Bibcode:2012ApJ...751L..37D, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/751/2/L37

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Neufeld, David A.; et al. (1997), "Discovery of Interstellar Hydrogen Fluoride", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 488 (2): L141–L144, arXiv:astro-ph/9708013, Bibcode:1997ApJ...488L.141N, doi:10.1086/310942

- ^ Wyrowski, F.; et al. (2009), "First interstellar detection of OH+", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 518: A26, arXiv:1004.2627, Bibcode:2010A&A...518A..26W, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014364

- ^ Meyer, D. M.; Roth, K. C. (1991), "Discovery of interstellar NH", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 376: L49–L52, Bibcode:1991ApJ...376L..49M, doi:10.1086/186100

- ^ Wagenblast, R.; et al. (January 1993), "On the origin of NH in diffuse interstellar clouds", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 260 (2): 420–424, Bibcode:1993MNRAS.260..420W, doi:10.1093/mnras/260.2.420

- ^ <Please add first missing authors to populate metadata.> (June 9, 2004), Astronomers Detect Molecular Nitrogen Outside Solar System, Space Daily, retrieved 2010-06-25

- ^ Knauth, D. C; et al. (2004), "The interstellar N2 abundance towards HD 124314 from far-ultraviolet observations", Nature, 429 (6992): 636–638, Bibcode:2004Natur.429..636K, doi:10.1038/nature02614, PMID 15190346, retrieved 2010-06-25

- ^ McGonagle, D.; et al. (1990), "Detection of nitric oxide in the dark cloud L134N", Astrophysical Journal, Part 1, 359: 121–124, Bibcode:1990ApJ...359..121M, doi:10.1086/169040

- ^ Whiteoak, J. B.; Gardner, F. F. (1985), "Interstellar NaI absorption towards the stellar association ARA OB1", Astronomical Society of Australia, Proceedings, 6 (2), Sydney: 164–171, Bibcode:1985PASAu...6..164W

- ^ Staff writers (March 27, 2007), Elusive oxygen molecule finally discovered in interstellar space, Physorg.com, retrieved 2007-04-02

- ^ Ziurys, L. M. (1987), "Detection of interstellar PN - The first phosphorus-bearing species observed in molecular clouds", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 321: L81–L85, Bibcode:1987ApJ...321L..81Z, doi:10.1086/185010

- ^ Tenenbaum, E. D.; Woolf, N. J.; Ziurys, L. M. (2007), "Identification of phosphorus monoxide (X 2 Pi r) in VY Canis Majoris: Detection of the first PO bond in space", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 666: L29–L32, Bibcode:2007ApJ...666L..29T, doi:10.1086/521361

- ^ Yamamura, S. T.; Kawaguchi, K.; Ridgway, S. T. (2000), "Identification of SH v=1 Ro-vibrational Lines in R Andromedae", The Astrophysical Journal, 528 (1): L33–L36, arXiv:astro-ph/9911080, Bibcode:2000ApJ...528L..33Y, doi:10.1086/312420, PMID 10587489

- ^ Menten, K. M.; et al. (2011), "Submillimeter Absorption from SH+, a New Widespread Interstellar Radical, 13CH+ and HCl", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 525: A77, arXiv:1009.2825, Bibcode:2011A&A...525A..77M, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014363, retrieved 2010-12-03.

- ^ a b c Pascoli, G.; Comeau, M. (1995), "Silicon Carbide in Circumstellar Environment", Astrophysics and Space Science, 226: 149–163, Bibcode:1995Ap&SS.226..149P, doi:10.1007/BF00626907

- ^ a b Kamiński, T.; et al. (2013), "Pure rotational spectra of TiO and TiO2 in VY Canis Majoris", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 551: A113, arXiv:1301.4344, Bibcode:2013A&A...551A.113K, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201220290

- ^ a b Oka, Takeshi (2006), "Interstellar H3+", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103 (33): 12235–12242, Bibcode:2006PNAS..10312235O, doi:10.1073/pnas.0601242103, PMC 1567864, PMID 16894171, retrieved 2007-02-04

- ^ a b Geballe, T. R.; Oka, T. (1996), "Detection of H3+ in Interstellar Space", Nature, 384 (6607): 334–335, Bibcode:1996Natur.384..334G, doi:10.1038/384334a0, PMID 8934516

- ^ Tenenbaum, E. D.; Ziurys, L. M. (2010), "Exotic Metal Molecules in Oxygen-rich Envelopes: Detection of AlOH (X1Σ+) in VY Canis Majoris", Astrophysical Journal, 712: L93–L97, Bibcode:2010ApJ...712L..93T, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/712/1/L93

- ^ Anderson, J. K.; et al. (2014), "Detection of CCN (X2Πr) in IRC+10216: Constraining Carbon-chain Chemistry", Astrophysical Journal, 795: L1, Bibcode:2014ApJ...795L...1A, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/795/1/L1

- ^ Ohishi, Masatoshi, Masatoshi; et al. (1991), "Detection of a new carbon-chain molecule, CCO", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 380: L39–L42, Bibcode:1991ApJ...380L..39O, doi:10.1086/186168

- ^ a b c d Irvine, William M.; et al. (1988), "Newly detected molecules in dense interstellar clouds", Astrophysical Letters and Communications, 26: 167–180, Bibcode:1988ApL&C..26..167I, PMID 11538461

- ^ Halfen, D. T.; Clouthier, D. J.; Ziurys, L. M. (2008), "Detection of the CCP Radical (X 2Πr) in IRC +10216: A New Interstellar Phosphorus-containing Species", Astrophysical Journal, 677 (2): L101–L104, Bibcode:2008ApJ...677L.101H, doi:10.1086/588024

- ^ Whittet, D. C. B.; Walker, H. J. (1991), "On the occurrence of carbon dioxide in interstellar grain mantles and ion-molecule chemistry", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 252: 63–67, Bibcode:1991MNRAS.252...63W, doi:10.1093/mnras/252.1.63

- ^ Zack, L. N.; Halfen, D. T.; Ziurys, L. M. (June 2011), "Detection of FeCN (X 4Δi) in IRC+10216: A New Interstellar Molecule", The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 733 (2): L36, Bibcode:2011ApJ...733L..36Z, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/733/2/L36

- ^ Hollis, J. M.; Jewell, P. R.; Lovas, F. J. (1995), "Confirmation of interstellar methylene", Astrophysical Journal, Part 1, 438: 259–264, Bibcode:1995ApJ...438..259H, doi:10.1086/175070

- ^ Lis, D. C.; et al. (2010-10-01), "Herschel/HIFI discovery of interstellar chloronium (H2Cl+)", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 521: L9, arXiv:1007.1461, Bibcode:2010A&A...521L...9L, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014959.

- ^ Europe's space telescope ISO finds water in distant places, ESO, April 29, 1997, archived from the original on 2006-12-22, retrieved 2007-02-08

- ^ Ossenkopf, V.; et al. (2010), "Detection of interstellar oxidaniumyl: Abundant H2O+ towards the star-forming regions DR21, Sgr B2, and NGC6334", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 518: L111, arXiv:1005.2521, Bibcode:2010A&A...518L.111O, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014577.

- ^ Parise, B.; Bergman, P.; Du, F. (2012), "Detection of the hydroperoxyl radical HO2 toward ρ Ophiuchi A. Additional constraints on the water chemical network", Astronomy & Astrophysics Letters, 541: L11–L14, arXiv:1205.0361, Bibcode:2012A&A...541L..11P, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219379

- ^ Snyder, L. E.; Buhl, D. (1971), "Observations of Radio Emission from Interstellar Hydrogen Cyanide", Astrophysical Journal, 163: L47–L52, Bibcode:1971ApJ...163L..47S, doi:10.1086/180664

- ^ a b Schilke, P.; Benford, D. J.; Hunter, T. R.; Lis, D. C., Phillips, T. G.; Phillips, T. G. (2001), "A Line Survey of Orion-KL from 607 to 725 GHz", Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 132 (2): 281–364, Bibcode:2001ApJS..132..281S, doi:10.1086/318951

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Schenewerk, M. S.; Snyder, L. E.; Hjalmarson, A. (1986), "Interstellar HCO - Detection of the missing 3 millimeter quartet", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 303: L71–L74, Bibcode:1986ApJ...303L..71S, doi:10.1086/184655

- ^ a b c d e f Kawaguchi, Kentarou; et al. (1994), "Detection of a new molecular ion HC3NH(+) in TMC-1", Astrophysical Journal, 420: L95, Bibcode:1994ApJ...420L..95K, doi:10.1086/187171

- ^ Agúndez, M.; Cernicharo, J.; Guélin, M. (2007), "Discovery of Phosphaethyne (HCP) in Space: Phosphorus Chemistry in Circumstellar Envelopes", The Astrophysical Journal, 662 (2): L91, Bibcode:2007ApJ...662L..91A, doi:10.1086/519561, retrieved 2007-06-02

- ^ Schilke, P.; Comito, C.; Thorwirth, S. (2003), "First Detection of Vibrationally Excited HNC in Space", The Astrophysical Journal, 582 (2): L101–L104, Bibcode:2003ApJ...582L.101S, doi:10.1086/367628, retrieved 2008-09-14

- ^ Hollis, J. M.; et al. (1991), "Interstellar HNO: Confirming the Identification - Atoms, ions and molecules: New results in spectral line astrophysics", Atoms, 16, San Francisco: ASP: 407–412, Bibcode:1991ASPC...16..407H

- ^ van Dishoeck, Ewine F.; et al. (1993), "Detection of the Interstellar NH 2 Radical", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 416: L83–L86, Bibcode:1993ApJ...416L..83V, doi:10.1086/187076

- ^ Womack, M.; Ziurys, L. M.; Wyckoff, S. (1992), "A survey of N2H(+) in dense clouds - Implications for interstellar nitrogen and ion-molecule chemistry", Astrophysical Journal, Part 1, 387: 417–429, Bibcode:1992ApJ...387..417W, doi:10.1086/171094

- ^ Ziurys, L. M.; et al. (1994), "Detection of interstellar N2O: A new molecule containing an N-O bond", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 436: L181–L184, Bibcode:1994ApJ...436L.181Z, doi:10.1086/187662

- ^ Hollis, J. M.; Rhodes, P. J. (November 1, 1982), "Detection of interstellar sodium hydroxide in self-absorption toward the galactic center", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 262: L1–L5, Bibcode:1982ApJ...262L...1H, doi:10.1086/183900

- ^ Goldsmith, P. F.; Linke, R. A. (1981), "A study of interstellar carbonyl sulfide", Astrophysical Journal, Part 1, 245: 482–494, Bibcode:1981ApJ...245..482G, doi:10.1086/158824

- ^ Phillips, T. G.; Knapp, G. R. (1980), "Interstellar Ozone", American Astronomical Society Bulletin, 12: 440, Bibcode:1980BAAS...12..440P

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Johansson, L. E. B.; et al. (1984), "Spectral scan of Orion A and IRC+10216 from 72 to 91 GHz", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 130 (2): 227–256, Bibcode:1984A&A...130..227J

- ^ Cernicharo, José; et al. (2015), "Discovery of SiCSi in IRC+10216: a Missing Link Between Gas and Dust Carriers OF Si–C Bonds", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 806: L3, Bibcode:2015ApJ...806L...3C, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/806/1/L3

- ^ Guélin, M.; et al. (2004), "Astronomical detection of the free radical SiCN", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 363: L9–L12, Bibcode:2000A&A...363L...9G

- ^ Guélin, M.; et al. (2004), "Detection of the SiNC radical in IRC+10216", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 426 (2): L49–L52, Bibcode:2004A&A...426L..49G, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200400074

- ^ a b Snyder, Lewis E.; et al. (1999), "Microwave Detection of Interstellar Formaldehyde", Physical Review Letters, 61 (2): 77–115, Bibcode:1969PhRvL..22..679S, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.22.679

- ^ Feuchtgruber, H.; et al. (June 2000), "Detection of Interstellar CH3", The Astrophysical Journal, 535 (2): L111–L114, arXiv:astro-ph/0005273, Bibcode:2000ApJ...535L.111F, doi:10.1086/312711, PMID 10835311

- ^ a b Irvine, W. M.; et al. (1984), "Confirmation of the Existence of Two New Interstellar Molecules: C3H and C3O", Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, 16: 877, Bibcode:1984BAAS...16..877I

- ^ Pety, J.; et al. (2012), "The IRAM-30 m line survey of the Horsehead PDR. II. First detection of the l-C3MH+ hydrocarbon cation", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 548: A68, arXiv:1210.8178, Bibcode:2012A&A...548A..68P, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201220062

- ^ Mangum, J. G.; Wootten, A. (1990), "Observations of the cyclic C3H radical in the interstellar medium", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 239: 319–325, Bibcode:1990A&A...239..319M

- ^ Bell, M. B.; Matthews, H. E. (1995), "Detection of C3N in the spiral arm gas clouds in the direction of Cassiopeia A", Astrophysical Journal, Part 1, 438: 223–225, Bibcode:1995ApJ...438..223B, doi:10.1086/175066

- ^ Thaddeus, P.; et al. (2008), "Laboratory and Astronomical Detection of the Negative Molecular Ion C3N-", The Astrophysical Journal, 677 (2): 1132–1139, Bibcode:2008ApJ...677.1132T, doi:10.1086/528947

- ^ Wootten, Alwyn; et al. (1991), "Detection of interstellar H3O(+) - A confirming line", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 380: L79–L83, Bibcode:1991ApJ...380L..79W, doi:10.1086/186178

- ^ Ridgway, S. T.; et al. (1976), "Circumstellar acetylene in the infrared spectrum of IRC+10216", Nature, 264: 345, 346, Bibcode:1976Natur.264..345R, doi:10.1038/264345a0

- ^ Ohishi, Masatoshi; et al. (1994), "Detection of a new interstellar molecule, H2CN", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 427: L51–L54, Bibcode:1994ApJ...427L..51O, doi:10.1086/187362

- ^ Minh, Y. C.; Irvine, W. M.; Brewer, M. K. (1991), "H2CS abundances and ortho-to-para ratios in interstellar clouds", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 244: 181–189, Bibcode:1991A&A...244..181M, PMID 11538284

- ^ Guelin, M.; Cernicharo, J. (1991), "Astronomical detection of the HCCN radical - Toward a new family of carbon-chain molecules?", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 244: L21–L24, Bibcode:1991A&A...244L..21G

- ^ Agúndez, M.; et al. (2015), "Discovery of interstellar ketenyl (HCCO), a surprisingly abundant radical", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 577: L5, Bibcode:2015A&A...577L...5A, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201526317

- ^ Minh, Y. C.; Irvine, W. M.; Ziurys, L. M. (1988), "Observations of interstellar HOCO(+) - Abundance enhancements toward the Galactic center", Astrophysical Journal, Part 1, 334: 175–181, Bibcode:1988ApJ...334..175M, doi:10.1086/166827

- ^ Marcelino, Núria; et al. (2009), "Discovery of fulminic acid, HCNO, in dark clouds", Astrophysical Journal, 690: L27–L30, arXiv:0811.2679, Bibcode:2009ApJ...690L..27M, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/690/1/L27

- ^ Brünken, S.; et al. (2010-07-22), "Interstellar HOCN in the Galactic center region", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 516: A109, arXiv:1005.2489, Bibcode:2010A&A...516A.109B, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912456

- ^ Bergman; Parise; Liseau; Larsson; Olofsson; Menten; Güsten (2011), "Detection of interstellar hydrogen peroxide", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 531: L8, arXiv:1105.5799, Bibcode:2011A&A...531L...8B, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117170.

- ^ Frerking, M. A.; Linke, R. A.; Thaddeus, P. (1979), "Interstellar isothiocyanic acid", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 234: L143–L145, Bibcode:1979ApJ...234L.143F, doi:10.1086/183126

- ^ a b Nguyen-Q-Rieu; Graham, D.; Bujarrabal, V. (1984), "Ammonia and cyanotriacetylene in the envelopes of CRL 2688 and IRC + 10216", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 138 (1): L5–L8, Bibcode:1984A&A...138L...5N

- ^ Halfen, D. T.; et al. (September 2009), "Detection of a New Interstellar Molecule: Thiocyanic Acid HSCN", The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 702 (2): L124–L127, Bibcode:2009ApJ...702L.124H, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/702/2/L124

- ^ Cabezas, C.; et al. (2013), "Laboratory and Astronomical Discovery of Hydromagnesium Isocyanide", Astrophysical Journal, 775: 133, arXiv:1309.0371, Bibcode:2013ApJ...775..133C, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/775/2/133

- ^ Butterworth, Anna L.; et al. (2004), "Combined element (H and C) stable isotope ratios of methane in carbonaceous chondrites", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 347 (3): 807–812, Bibcode:2004MNRAS.347..807B, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.07251.x

- ^ http://www.astro.uni-koeln.de/site/vorhersagen/molecules/ism/Ammonium.html

- ^ http://iopscience.iop.org/2041-8205/771/1/L10/

- ^ Lacy, J. H.; et al. (1991), "Discovery of interstellar methane - Observations of gaseous and solid CH4 absorption toward young stars in molecular clouds", Astrophysical Journal, 376: 556–560, Bibcode:1991ApJ...376..556L, doi:10.1086/170304

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cernicharo, J.; Marcelino, N.; Roueff, E.; Gerin, M.; Jiménez-Escobar, A.; Muñoz Caro, G. M. (2012), "Discovery of the Methoxy Radical, CH3O, toward B1: Dust Grain and Gas-phase Chemistry in Cold Dark Clouds", The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 759 (2): L43–L46, Bibcode:2012ApJ...759L..43C, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/759/2/L43

- ^ a b c d e f g h Finley, Dave (August 7, 2006), Researchers Use NRAO Telescope to Study Formation Of Chemical Precursors to Life, National Radio Astronomy Observatory, retrieved 2006-08-10

- ^ a b c Fossé, David; et al. (2001), "Molecular Carbon Chains and Rings in TMC-1", Astrophysical Journal, 552 (1): 168–174, arXiv:astro-ph/0012405, Bibcode:2001ApJ...552..168F, doi:10.1086/320471, retrieved 2008-09-14

- ^ Irvine, W. M.; et al. (1988), "Identification of the interstellar cyanomethyl radical (CH2CN) in the molecular clouds TMC-1 and Sagittarius B2", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 334: L107–L111, Bibcode:1988ApJ...334L.107I, doi:10.1086/185323

- ^ Dickens, J. E.; et al. (1997), "Hydrogenation of Interstellar Molecules: A Survey for Methylenimine (CH2NH)", Astrophysical Journal, 479 (1 Pt 1): 307–12, Bibcode:1997ApJ...479..307D, doi:10.1086/303884, PMID 11541227

- ^ McGuire, B.A.; et al. (2012), "Interstellar Carbodiimide (HNCNH): A New Astronomical Detection from the GBT PRIMOS Survey via Maser Emission Features", The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 758 (2): L33–L38, arXiv:1209.1590, Bibcode:2012ApJ...758L..33M, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/758/2/L33

- ^ Ohishi, Masatoshi; et al. (1996), "Detection of a New Interstellar Molecular Ion, H2COH+ (Protonated Formaldehyde)", Astrophysical Journal, 471 (1): L61–4, Bibcode:1996ApJ...471L..61O, doi:10.1086/310325, PMID 11541244

- ^ Cernicharo, J.; et al. (2007), "Astronomical detection of C4H−, the second interstellar anion", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 61 (2): L37–L40, Bibcode:2007A&A...467L..37C, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20077415

- ^ a b c Liu, S.-Y.; Mehringer, D. M.; Snyder, L. E. (2001), "Observations of Formic Acid in Hot Molecular Cores", Astrophysical Journal, 552 (2): 654–663, Bibcode:2001ApJ...552..654L, doi:10.1086/320563

- ^ a b Walmsley, C. M.; Winnewisser, G.; Toelle, F. (1990), "Cyanoacetylene and cyanodiacetylene in interstellar clouds", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 81 (1–2): 245–250, Bibcode:1980A&A....81..245W

- ^ Kawaguchi, Kentarou; et al. (1992), "Detection of isocyanoacetylene HCCNC in TMC-1", Astrophysical Journal, 386 (2): L51–L53, Bibcode:1992ApJ...386L..51K, doi:10.1086/186290

- ^ Zuckerman, B.; Ball, John A.; Gottleib, Carl A. (1971). "Microwave Detection of Interstellar Formic Acid". Astrophysical Journal. 163: L41. Bibcode:1971ApJ...163L..41Z. doi:10.1086/180663.

- ^ Turner, B. E.; et al. (1975), "Microwave detection of interstellar cyanamide", Astrophysical Journal, 201: L149–L152, Bibcode:1975ApJ...201L.149T, doi:10.1086/181963

- ^ Agúndez, M.; et al. (2015), "Probing non-polar interstellar molecules through their protonated form: Detection of protonated cyanogen (NCCNH+)", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 579: L10, arXiv:1506.07043, Bibcode:2015A&A...579L..10A, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201526650

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Remijan, Anthony J.; et al. (2008), "Detection of interstellar cyanoformaldehyde (CNCHO)", Astrophysical Journal, 675 (2): L85–L88, Bibcode:2008ApJ...675L..85R, doi:10.1086/533529

- ^ Goldhaber, D. M.; Betz, A. L. (1984), "Silane in IRC +10216", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 279: –L55–L58, Bibcode:1984ApJ...279L..55G, doi:10.1086/184255

- ^ a b c Hollis, J. M.; et al. (2006), "Detection of Acetamide (CH3CONH2): The Largest Interstellar Molecule with a Peptide Bond", Astrophysical Journal, 643 (1): L25–L28, Bibcode:2006ApJ...643L..25H, doi:10.1086/505110

- ^ Hollis, J. M.; et al. (2006), "Cyclopropenone (c-H2C3O): A New Interstellar Ring Molecule", Astrophysical Journal, 642 (2): 933–939, Bibcode:2006ApJ...642..933H, doi:10.1086/501121

- ^ Zaleski, D. P.; et al. (2013), "Detection of E-Cyanomethanimine toward Sagittarius B2(N) in the Green Bank Telescope PRIMOS Survey", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 765: L109, arXiv:1302.0909, Bibcode:2013ApJ...765L..10Z, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/765/1/L10

- ^ Betz, A. L. (1981), "Ethylene in IRC +10216", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 244: –L105, Bibcode:1981ApJ...244L.103B, doi:10.1086/183490

- ^ a b c d e Remijan, Anthony J.; et al. (2005), "Interstellar Isomers: The Importance of Bonding Energy Differences", Astrophysical Journal, 632 (1): 333–339, arXiv:astro-ph/0506502, Bibcode:2005ApJ...632..333R, doi:10.1086/432908

- ^ "Complex Organic Molecules Discovered in Infant Star System". NRAO. Astrobiology Web. 8 April 2015. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- ^ First Detection of Methyl Alcohol in a Planet-forming Disc. 15 June 2016.

- ^ Lambert, D. L.; Sheffer, Y.; Federman, S. R. (1979), "Interstellar methyl mercaptan", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 234: L139–L142, Bibcode:1979ApJ...234L.139L, doi:10.1086/183125

- ^ a b c Cernicharo, José; et al. (1997), "Infrared Space Observatory's Discovery of C4H2, C6H2, and Benzene in CRL 618", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 546 (2): L123–L126, Bibcode:2001ApJ...546L.123C, doi:10.1086/318871

- ^ Guelin, M.; Neininger, N.; Cernicharo, J. (1998), "Astronomical detection of the cyanobutadiynyl radical C_5N", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 335: L1–L4, arXiv:astro-ph/9805105, Bibcode:1998A&A...335L...1G

- ^ Irvine, W. M.; et al. (1988), "A new interstellar polyatomic molecule - Detection of propynal in the cold cloud TMC-1", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 335: L89–L93, Bibcode:1988ApJ...335L..89I, doi:10.1086/185346

- ^ a b c d Agúndez, M.; et al. (2014), "New molecules in IRC +10216: confirmation of C5S and tentative identification of MgCCH, NCCP, and SiH3CN", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 570: A45, Bibcode:2014A&A...570A..45A, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201424542

- ^ a b Scientists Toast the Discovery of Vinyl Alcohol in Interstellar Space, National Radio Astronomy Observatory, October 1, 2001, retrieved 2006-12-20

- ^ a b Dickens, J. E.; et al. (1997), "Detection of Interstellar Ethylene Oxide (c-C2H4O)", The Astrophysical Journal, 489 (2): 753–757, Bibcode:1997ApJ...489..753D, doi:10.1086/304821, PMID 11541726

- ^ Kaifu, N.; Takagi, K.; Kojima, T. (1975), "Excitation of interstellar methylamine", Astrophysical Journal, 198: L85–L88, Bibcode:1975ApJ...198L..85K, doi:10.1086/181818

- ^ McCarthy, M. C.; et al. (2006), "Laboratory and Astronomical Identification of the Negative Molecular Ion C6H−", Astrophysical Journal, 652 (2): L141–L144, Bibcode:2006ApJ...652L.141M, doi:10.1086/510238

- ^ Halfven, D. T.; et al. (2015), "INTERSTELLAR DETECTION OF METHYL ISOCYANATE CH3NCO IN Sgr B2(N): A LINK FROM MOLECULAR CLOUDS TO COMETS", Astrophysical Journal, 812: L5, arXiv:1509.09305, Bibcode:2015ApJ...812L...5H, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/812/1/L5

- ^ a b Mehringer, David M.; et al. (1997), "Detection and Confirmation of Interstellar Acetic Acid", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 480: L71, Bibcode:1997ApJ...480L..71M, doi:10.1086/310612

- ^ a b Lovas, F. J.; et al. (2006), "Hyperfine Structure Identification of Interstellar Cyanoallene toward TMC-1", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 637 (1): L37–L40, Bibcode:2006ApJ...637L..37L, doi:10.1086/500431

- ^ a b Sincell, Mark (June 27, 2006), "The Sweet Signal of Sugar in Space", Science, American Association for the Advancement of Science, retrieved 2016-01-14

- ^ Loomis, R. A.; et al. (2013), "The Detection of Interstellar Ethanimine CH3CHNH) from Observations Taken during the GBT PRIMOS Survey", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 765: L9, arXiv:1302.1121, Bibcode:2013ApJ...765L...9L, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/765/1/L9

- ^ Guelin, M.; et al. (1997), "Detection of a new linear carbon chain radical: C7H", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 317: L37–L40, Bibcode:1997A&A...317L...1G

- ^ Belloche, A.; et al. (2008), "Detection of amino acetonitrile in Sgr B2(N)", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 482: 179–196, arXiv:0801.3219, Bibcode:2008A&A...482..179B, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20079203

- ^ Remijan, Anthony J.; et al. (2014), "OBSERVATIONAL RESULTS OF A MULTI-TELESCOPE CAMPAIGN IN SEARCH OF INTERSTELLAR UREA [(NH2)2CO]", Astrophysical Journal, 783 (2): 77, arXiv:1401.4483, Bibcode:2014ApJ...783...77R, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/783/2/77

- ^ a b Remijan, Anthony J.; et al. (2006), "Methyltriacetylene (CH3C6H) toward TMC-1: The Largest Detected Symmetric Top", Astrophysical Journal, 643 (1): L37–L40, Bibcode:2006ApJ...643L..37R, doi:10.1086/504918

- ^ Snyder, L. E.; et al. (1974), "Radio Detection of Interstellar Dimethyl Ether", Astrophysical Journal, 191: L79–L82, Bibcode:1974ApJ...191L..79S, doi:10.1086/181554

- ^ Zuckerman, B.; et al. (1975), "Detection of interstellar trans-ethyl alcohol", Astrophysical Journal, 196 (2): L99–L102, Bibcode:1975ApJ...196L..99Z, doi:10.1086/181753

- ^ Cernicharo, J.; Guelin, M. (1996), "Discovery of the C8H radical", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 309: L26–L30, Bibcode:1996A&A...309L..27C

- ^ Brünken, S.; et al. (2007), "Detection of the Carbon Chain Negative Ion C8H− in TMC-1", Astrophysical Journal, 664 (1): L43–L46, Bibcode:2007ApJ...664L..43B, doi:10.1086/520703

- ^ Remijan, Anthony J.; et al. (2007), "Detection of C8H− and Comparison with C8H toward IRC +10 216", Astrophysical Journal, 664 (1): L47–L50, Bibcode:2007ApJ...664L..47R, doi:10.1086/520704

- ^ a b c d Bell, M. B.; et al. (1997), "Detection of HC11N in the Cold Dust Cloud TMC-1", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 483 (1): L61–L64, arXiv:astro-ph/9704233, Bibcode:1997ApJ...483L..61B, doi:10.1086/310732

- ^ Kroto, H. W.; et al. (1978), "The detection of cyanohexatriyne, H (C≡ C)3CN, in Heiles's cloud 2", The Astrophysical Journal, 219: L133–L137, Bibcode:1978ApJ...219L.133K, doi:10.1086/182623

- ^ Marcelino, N.; et al. (2007), "Discovery of Interstellar Propylene (CH2CHCH3): Missing Links in Interstellar Gas-Phase Chemistry", Astrophysical Journal, 665 (2): L127–L130, arXiv:0707.1308, Bibcode:2007ApJ...665L.127M, doi:10.1086/521398

- ^ Kolesniková, L.; et al. (2014), "Spectroscopic Characterization and Detection of Ethyl Mercaptan in Orion", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 784 (1): L7, arXiv:1401.7810, Bibcode:2014ApJ...784L...7K, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/784/1/L7

- ^ Snyder, Lewis E.; et al. (2002), "Confirmation of Interstellar Acetone", The Astrophysical Journal, 578 (1): 245–255, Bibcode:2002ApJ...578..245S, doi:10.1086/342273

- ^ Hollis, J. M.; et al. (2002), "Interstellar Antifreeze: Ethylene Glycol", Astrophysical Journal, 571 (1): L59–L62, Bibcode:2002ApJ...571L..59H, doi:10.1086/341148, retrieved 2010-07-18

- ^ Hollis, J. M. (2005), "Complex Molecules and the GBT: Is Isomerism the Key?" (PDF), Complex Molecules and the GBT: Is Isomerism the Key?, Proceedings of the IAU Symposium 231, Astrochemistry throughout the Universe, Asilomar, CA, pp. 119–127

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Discovery of the Interstellar Chiral Molecule Propylene Oxide (CH3CHCH2O), 27 June 2016.

- ^ a b Belloche, A.; et al. (May 2009), "Increased complexity in interstellar chemistry: Detection and chemical modeling of ethyl formate and n-propyl cyanide in Sgr B2(N)", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 499 (1): 215–232, arXiv:0902.4694, Bibcode:2009A&A...499..215B, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200811550

- ^ Tercero, B.; et al. (2013), "Discovery of Methyl Acetate and Gauche Ethyl Formate in Orion", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 770: L13, arXiv:1305.1135, Bibcode:2013ApJ...770L..13T, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/770/1/L13

- ^ Eyre, Michael (26 September 2014). "Complex organic molecule found in interstellar space". BBC News. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

- ^ Belloche, Arnaud; Garrod, Robin T.; Müller, Holger S. P.; Menten, Karl M. (26 September 2014). "Detection of a branched alkyl molecule in the interstellar medium: iso-propyl cyanide". Science. 345 (6204): 1584–1587. arXiv:1410.2607. Bibcode:2014Sci...345.1584B. doi:10.1126/science.1256678. PMID 25258074. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

- ^ a b Cami, Jan; et al. (July 22, 2010), "Detection of C60 and C70 in a Young Planetary Nebula", Science, 329 (5996): 1180–2, Bibcode:2010Sci...329.1180C, doi:10.1126/science.1192035, PMID 20651118

- ^ Foing, B. H.; Ehrenfreund, P. (1994), "Detection of two interstellar absorption bands coincident with spectral features of C60+", Nature, 369 (6478): 296–298, Bibcode:1994Natur.369..296F, doi:10.1038/369296a0.

- ^ Berné, Olivier; Mulas, Giacomo; Joblin, Christine (2013), "Interstellar C60+", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 550: L4, arXiv:1211.7252, Bibcode:2013A&A...550L...4B, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201220730

- ^ a b Lacour, S.; et al. (2005), "Deuterated molecular hydrogen in the Galactic ISM. New observations along seven translucent sightlines", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 430 (3): 967–977, arXiv:astro-ph/0410033, Bibcode:2005A&A...430..967L, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20041589

- ^ a b c d Ceccarelli, Cecilia (2002), "Millimeter and infrared observations of deuterated molecules", Planetary and Space Science, 50 (12–13): 1267–1273, Bibcode:2002P&SS...50.1267C, doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(02)00093-4

- ^ Green, Sheldon (1989), "Collisional excitation of interstellar molecules - Deuterated water, HDO", Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 70: 813–831, Bibcode:1989ApJS...70..813G, doi:10.1086/191358

- ^ Butner, H. M.; et al. (2007), "Discovery of interstellar heavy water", Astrophysical Journal, 659 (2): L137–L140, Bibcode:2007ApJ...659L.137B, doi:10.1086/517883

- ^ a b c d Turner, B. E.; Zuckerman, B. (1978), "Observations of strongly deuterated molecules - Implications for interstellar chemistry", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 225: L75–L79, Bibcode:1978ApJ...225L..75T, doi:10.1086/182797

- ^ Lis, D. C.; et al. (2002), "Detection of Triply Deuterated Ammonia in the Barnard 1 Cloud", Astrophysical Journal, 571 (1): L55–L58, Bibcode:2002ApJ...571L..55L, doi:10.1086/341132.

- ^ Hatchell, J. (2003), "High NH2D/NH3 ratios in protostellar cores", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 403 (2): L25–L28, arXiv:astro-ph/0302564, Bibcode:2003A&A...403L..25H, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20030297.

- ^ Turner, B. E. (1990), "Detection of doubly deuterated interstellar formaldehyde (D2CO) - an indicator of active grain surface chemistry", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 362: L29–L33, Bibcode:1990ApJ...362L..29T, doi:10.1086/185840.

- ^ a b Coutens, A.; et al. (9 May 2016). "The ALMA-PILS survey: First detections of deuterated formamide and deuterated isocyanic acid in the interstellar medium". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 590: L6. arXiv:1605.02562. Bibcode:2016A&A...590L...6C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201628612.

- ^ Cernicharo, J.; et al. (2013), "Detection of the Ammonium ion in space", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 771: L10, arXiv:1306.3364, Bibcode:2013ApJ...771L..10C, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/771/1/L10

- ^ Doménech, J. L.; et al. (2013), "Improved Determinination of the 10-00 Rotational Frequency of NH3D+ from the High-Resolution Spectrum of the ν4 Infrared Band", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 771: L11, arXiv:1306.3792, Bibcode:2013ApJ...771L..11D, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/771/1/L10

- ^ Gerin, M.; et al. (1992), "Interstellar detection of deuterated methyl acetylene", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 253 (2): L29–L32, Bibcode:1992A&A...253L..29G.

- ^ Markwick, A. J.; Charnley, S. B.; Butner, H. M.; Millar, T. J. (2005), "Interstellar CH3CCD", The Astrophysical Journal, 627 (2): L117–L120, Bibcode:2005ApJ...627L.117M, doi:10.1086/432415.

- ^ Agúndez, M.; et al. (2008-06-04), "Tentative detection of phosphine in IRC +10216", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 485 (3): L33, arXiv:0805.4297, Bibcode:2008A&A...485L..33A, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200810193

- ^ Gupta, H.; et al. (2013), "Laboratory Measurements and Tentative Astronomical Identification of H2NCO+", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 778: L1, Bibcode:2013ApJ...778L...1G, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/778/1/L1

- ^ Snyder, L. E.; et al. (2005), "A Rigorous Attempt to Verify Interstellar Glycine", Astrophysical Journal, 619 (2): 914–930, arXiv:astro-ph/0410335, Bibcode:2005ApJ...619..914S, doi:10.1086/426677.

- ^ Kuan, Y. J.; et al. (2003), "Interstellar Glycine", Astrophysical Journal, 593 (2): 848–867, Bibcode:2003ApJ...593..848K, doi:10.1086/375637.

- ^ Widicus Weaver, S. L.; Blake, G. A. (2005), "1,3-Dihydroxyacetone in Sagittarius B2(N-LMH): The First Interstellar Ketose", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 624 (1): L33–L36, Bibcode:2005ApJ...624L..33W, doi:10.1086/430407

- ^ Fuchs, G. W.; et al. (2005), "Trans-Ethyl Methyl Ether in Space: A new Look at a Complex Molecule in Selected Hot Core Regions", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 444 (2): 521–530, arXiv:astro-ph/0508395, Bibcode:2005A&A...444..521F, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053599, retrieved 2010-07-18

- ^ Iglesias-Groth, S.; et al. (2008-09-20), "Evidence for the Naphthalene Cation in a Region of the Interstellar Medium with Anomalous Microwave Emission", The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 685: L55–L58, arXiv:0809.0778, Bibcode:2008ApJ...685L..55I, doi:10.1086/592349 - This spectral assignment has not been independently confirmed, and is described by the authors as "tentative" (page L58).

- ^ García-Hernández, D. A.; et al. (2011), "The Formation of Fullerenes: Clues from New C60, C70, and (Possible) Planar C24 Detections in Magellanic Cloud Planetary Nebulae", Astrophysical Journal Letters, 737 (2): L30, arXiv:1107.2595, Bibcode:2011ApJ...737L..30G, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/737/2/L30, retrieved 2011-08-12.

- ^ Iglesias-Groth, S.; et al. (May 2010), "A search for interstellar anthracene toward the Perseus anomalous microwave emission region", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 407 (4): 2157–2165, arXiv:1005.4388, Bibcode:2010MNRAS.407.2157I, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17075.x

External links

- Woon, David E. (October 1, 2010). "Interstellar and Circumstellar Molecules". Retrieved 2010-10-04.

- "Molecules in Space". Universität zu Köln. August 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-04.

- Dworkin, Jason P. (February 1, 2007). "Interstellar Molecules". NASA's Cosmic Ice Lab. Retrieved 2010-12-23.

- Wootten, Al (November 2005). "The 129 reported interstellar and circumstellar molecules". National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Retrieved 2007-02-13.

- Lovas, F. J.; Dragoset, R. A. (February 2004). "NIST Recommended Rest Frequencies for Observed Interstellar Molecular Microwave Transitions, 2002 Revision". National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 2007-02-13.