Miranda (moon)

| |||||||||

| Discovery | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovered by | Gerard P. Kuiper | ||||||||

| Discovery date | February 16, 1948 | ||||||||

| Designations | |||||||||

| Pronunciation | /m[invalid input: 'ɨ']ˈrændə/ mi-RAN-də | ||||||||

| Uranus V | |||||||||

| Adjectives | Mirandan, Mirandian | ||||||||

| Orbital characteristics | |||||||||

| 129 390 km | |||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.0013 | ||||||||

| 1.413 479 d | |||||||||

| Inclination | 4.232° (to Uranus's equator) | ||||||||

| Satellite of | Uranus | ||||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||||

| Dimensions | 480×468.4×465.8 km | ||||||||

| 235.8 ± 0.7 km (0.03697 Earths)[1] | |||||||||

| 700 000 km2 | |||||||||

| Volume | 54 835 000 km3 | ||||||||

| Mass | 6.59 ± 0.75 kg[2] (1.103 Earths) | ||||||||

Mean density | 1.20 ± 0.15 g/cm3[2] | ||||||||

| 0.079 m/s2 | |||||||||

| 0.193 km/s | |||||||||

| synchronous | |||||||||

| 0° | |||||||||

| Albedo | 0.32 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| 15.8[4] | |||||||||

Miranda is the smallest and innermost of Uranus's five major moons.

It was discovered by Gerard Kuiper on February 16, 1948 at McDonald Observatory. It was named after Miranda from William Shakespeare's play The Tempest by Kuiper in his report of the discovery.[5] The adjectival form of the name is Mirandan. It is also designated Uranus V.

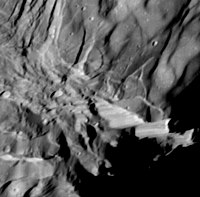

So far the only close-up images of Miranda are from the Voyager 2 probe, which made observations of the moon during its Uranus flyby in January 1986. During the flyby the southern hemisphere of the moon was pointed towards the Sun so only that part was studied. Miranda shows more evidence of past geologic activity than any of the other Uranian satellites.

Physical characteristics

Miranda's surface may be mostly water ice, with the low-density body also probably containing silicate rock and organic compounds in its interior.

Miranda's surface has patchwork regions of broken terrain indicating intense geological activity in the moon's past, and is criss-crossed by huge canyons. Large 'racetrack'-like grooved structures, called coronae, may have formed via extensional processes at the tops of diapirs, or upwellings of warm ice.[7][8] The ridges probably represent extensional tilt blocks. The canyons probably represent graben formed by extensional faulting. Other features may be due to cryovolcanic eruptions of icy magma. The diapirs may have changed the density distribution within the moon, which could have caused Miranda to reorient itself,[9] similar to a process believed to have occurred at Saturn's geologically active moon Enceladus.

Miranda's past geological activity is believed to have been driven by tidal heating at a time when its orbit was more eccentric than currently. Early in its history, Miranda was apparently captured into a 3:1 orbital resonance with Umbriel, from which it subsequently escaped.[10] The resonance would have increased orbital eccentricity; resulting tidal friction due to time-varying tidal forces from Uranus would have caused warming of the moon's interior. In the Uranian system, due to the planet's lesser degree of oblateness, and the larger relative size of its satellites, escape from a mean motion resonance is much easier than for satellites of Jupiter or Saturn. Miranda's orbital inclination (4.34°) is unusually high for a body so close to the planet. Miranda probably escaped from its resonance with Umbriel via a secondary resonance, and the mechanism of this escape is believed to explain why its orbital inclination is more than 10 times those of the other large Uranian moons (see moons of Uranus).[11][12]

Miranda may have also once been in a 5:3 resonance with Ariel, which would have also contributed to its internal heating. However, the maximum heating attributable to the resonance with Umbriel was likely about three times greater.[10]

An earlier theory, proposed shortly after the Voyager 2 flyby, was that a previous incarnation of Miranda was shattered by a massive impact, with the fragments reassembling and denser ones subsequently sinking to produce the current strange pattern.[7]

Scientists recognize the following geological features on Miranda:

- Craters

- Coronae (large ovoid features)

- Regiones (geological regions)

- Rupes (scarps)

- Sulci (parallel grooves)

See also

References

- ^

Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1016/0019-1035(88)90054-1 , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1016/0019-1035(88)90054-1instead. - ^ a b

Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1086/116211 , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1086/116211instead. - ^

Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1126/science.233.4759.70 , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1126/science.233.4759.70instead. - ^ "Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters". JPL (Solar System Dynamics). 2009-04-03. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- ^ Kuiper, G. P., The Fifth Satellite of Uranus, Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, Vol. 61, No. 360, p. 129, June 1949

- ^ "PIA00044: Miranda high resolution of large fault". JPL, NASA. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ a b c Chaikin, Andrew (2001-10-16). "Birth of Uranus' Provocative Moon Still Puzzles Scientists". Space.com. Imaginova Corp. Retrieved 2007-12-07. [dead link]

- ^

Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1029/97JE00802 , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1029/97JE00802instead. - ^

Pappalardo, Robert T.; Greeley, Ronald (1993). "Structural evidence for reorientation of Miranda about a paleo-pole". In Lunar and Planetary Inst., Twenty-Fourth Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Part 3: N-Z. pp. 1111–1112. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b

Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1016/0019-1035(90)90125-S , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1016/0019-1035(90)90125-Sinstead. - ^

Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1016/0019-1035(89)90070-5 , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1016/0019-1035(89)90070-5instead. - ^

Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1016/0019-1035(90)90126-T , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1016/0019-1035(90)90126-Tinstead.

External links

- Miranda Profile at NASA's Solar System Exploration site

- Miranda page at The

Nine8 Planets - Miranda, a Moon of Uranus at Views of the Solar System

- Paul Schenk's 3D images and flyover videos of Miranda and other outer solar system satellites

- Miranda Nomenclature from the USGS Planetary Nomenclature web site