OpenBSD

| OpenBSD logo with Puffy, the pufferfish. | |

"Free, Functional & Secure" | |

| Developer | The OpenBSD Project |

|---|---|

| OS family | BSD |

| Working state | Current |

| Source model | Open source |

| Initial release | 1 October 1996 |

| Latest release | 7.6 (8 October 2024) [±] |

| Repository | |

| Package manager | OpenBSD package tools and ports tree |

| Platforms | 68000, Alpha, AMD64, i386, MIPS, PowerPC, SPARC 32/64, VAX, Zaurus and others[1] |

| Kernel type | Monolithic |

| Userland | BSD |

| Default user interface | Modified pdksh, FVWM 2.2.5 for X11 |

| License | BSD, ISC |

| Official website | http://www.openbsd.org |

OpenBSD is a Unix-like computer operating system descended from Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD), a Unix derivative developed at the University of California, Berkeley. It was forked from NetBSD by project leader Theo de Raadt in late 1995. The project is widely known for the developers' insistence on open-source code and quality documentation, uncompromising position on software licensing, and focus on security and code correctness. The project is coordinated from de Raadt's home in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Its logo and mascot is a pufferfish named Puffy.

OpenBSD includes a number of security features absent or optional in other operating systems, and has a tradition in which developers audit the source code for software bugs and security problems. The project maintains strict policies on licensing and prefers the open-source BSD licence and its variants—in the past this has led to a comprehensive licence audit and moves to remove or replace code under licences found less acceptable.

As with most other BSD-based operating systems, the OpenBSD kernel and userland programs, such as the shell and common tools like cat and ps, are developed together in one source code repository. Third-party software is available as binary packages or may be built from source using the ports tree.

The OpenBSD project maintains ports for 17 different hardware platforms, including the DEC Alpha, Intel i386, Hewlett-Packard PA-RISC, AMD AMD64 and Motorola 68000 processors, Apple's PowerPC machines, Sun SPARC and SPARC64-based computers, the VAX and the Sharp Zaurus.[1] Template:Prerequiste-OpenBSD

History and popularity

In December 1994, NetBSD co-founder Theo de Raadt was asked to resign from his position as a senior developer and member of the NetBSD core team.[3] The reason for this is not wholly clear, although there are claims that it was due to personality clashes within the NetBSD project and on its mailing lists.[3] De Raadt has been criticized for having a sometimes abrasive personality: in his book, Free For All, Peter Wayner claims that de Raadt "began to rub some people the wrong way" before the split from NetBSD;[4] Linus Torvalds has described him as "difficult";[5] and an interviewer admits to being "apprehensive" before meeting him.[6] Many have different feelings: the same interviewer describes de Raadt's "transformation" on founding OpenBSD and his "desire to take care of his team," some find his straightforwardness refreshing, and few deny he is a talented coder[7] and security "guru".[8]

In October 1995, de Raadt founded OpenBSD, a new project forked from NetBSD 1.0. The initial release, OpenBSD 1.2, was made in July 1996, followed in October of the same year by OpenBSD 2.0.[9] Since then, the project has followed a schedule of a release every six months, each of which is maintained and supported for one year. The latest release, OpenBSD 4.9, appeared on May 1, 2011.

On 25 July 2007, OpenBSD developer Bob Beck announced the formation of the OpenBSD Foundation,[10] a Canadian not-for-profit corporation formed to "act as a single point of contact for persons and organizations requiring a legal entity to deal with when they wish to support OpenBSD."[11]

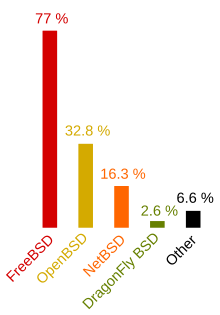

Just how widely OpenBSD is used is hard to ascertain: its developers neither publish nor collect usage statistics, and there are few other sources of information. In September 2005, the nascent BSD Certification Group performed a usage survey which revealed that 32.8% of BSD users (1420 of 4330 respondents) were using OpenBSD,[2] placing it second of the four major BSD variants, behind FreeBSD with 77% and ahead of NetBSD with 16.3%.[12] The DistroWatch website, well-known in the Linux community and often used as a reference for popularity, publishes page hits for each of the Linux distributions and other operating systems it covers. As of June 2011, using a data span of the last six months it placed FreeBSD in 15th place with 484 hits per day; PC-BSD in 24th place with 346 hits per day; GhostBSD in 53rd place with 171 hits, OpenBSD in 58th place with 164 hits per day; DragonFly in 62nd place with 142 hits per day; and NetBSD in 100th place with 94 hits per day.[13]

Open source and open documentation

When OpenBSD was created, Theo de Raadt decided that the source should be easily available for anyone to read at any time, so, with the assistance of Chuck Cranor,[14] he set up a public, anonymous CVS server. This was the first of its kind in the software development world: at the time, the tradition was for only a small team of developers to have access to a project's source repository.[15] Craner and de Raadt concluded that this practice "runs counter to the open source philosophy" and is inconvenient to contributors. de Raadt's decision allowed "users to take a more active role", and signaled the project's belief in open and public access to source code.[15]

A revealing incident regarding open documentation occurred in March 2005, when de Raadt posted a message[16] to the openbsd-misc mailing list. He announced that after four months of discussion, Adaptec had not disclosed the documentation required to improve the OpenBSD drivers for its AAC RAID controllers. As in similar circumstances in the past, he encouraged the OpenBSD community to become involved and express their opinion to Adaptec. Shortly after this, FreeBSD committer, former Adaptec employee and author of the FreeBSD AAC RAID support Scott Long,[17] castigated de Raadt[18] on the OSNews website for not contacting him directly regarding the issues with Adaptec. This caused the discussion to spill over onto the freebsd-questions mailing list, where the OpenBSD project leader countered[19] by claiming that he had received no previous offer of help from Scott Long nor been referred to him by Adaptec. The debate was amplified[20] by disagreements between members of the two camps regarding the use of binary blob drivers and non-disclosure agreements (NDAs): OpenBSD developers do not permit the inclusion of closed source binary drivers in the source tree and are reluctant to sign NDAs. However, the FreeBSD project has a different policy and much of the Adaptec RAID management code Scott Long proposed as assistance for OpenBSD was closed source or written under an NDA. As no documentation was forthcoming before the deadline for the release of OpenBSD 3.7, support for Adaptec AAC RAID controllers was removed from the standard OpenBSD kernel.[21]

The OpenBSD policy on openness extends to hardware documentation: in the slides for a December 2006 presentation, de Raadt explained that without it "developers often make mistakes writing drivers", and pointed out that "the [oh my god, I got it to work] rush is harder to achieve, and some developers just give up".[22] He went on to say that vendor binary drivers are unacceptable to OpenBSD, that they have "no trust of vendor binaries running in our kernel" and that there is "no way to fix [them] ... when they break".[22]

Licensing

A goal of the OpenBSD project is to "maintain the spirit of the original Berkeley Unix copyrights", which permitted a "relatively un-encumbered Unix source distribution".[23] To this end, the Internet Systems Consortium (ISC) licence, a simplified version of the BSD licence with wording removed that is unnecessary under the Berne convention, is preferred for new code, but the MIT or BSD licences are accepted. The widely used GNU General Public License is considered overly restrictive in comparison with these.[24]

In June 2001, triggered by concerns over Darren Reed's modification of IPFilter's licence wording, a systematic licence audit of the OpenBSD ports and source trees was undertaken.[25] Code in more than a hundred files throughout the system was found to be unlicensed, ambiguously licensed or in use against the terms of the licence. To ensure that all licences were properly adhered to, an attempt was made to contact all the relevant copyright holders: some pieces of code were removed, many were replaced, and others, including the multicast routing tools, mrinfo and map-mbone,[26] which were licensed by Xerox for research only, were relicensed so that OpenBSD could continue to use them; also removed during this audit was all software produced by Daniel J. Bernstein. At the time, Bernstein requested that all modified versions of his code be approved by him prior to redistribution, a requirement to which OpenBSD developers were unwilling to devote time or effort.[27] The removal led to a clash with Bernstein who felt the removal of his software to be uncalled for. He cited the Netscape web browser as much less freely licensed and accused the OpenBSD developers of hypocrisy for permitting Netscape to remain while removing his software.[28] The OpenBSD project's stance was that Netscape, although not open source, had licence conditions that could be more easily met.[29] They asserted that Bernstein's demand for control of derivatives would lead to a great deal of additional work and that removal was the most appropriate way to comply with his requirements.[29]

The OpenBSD team has developed software from scratch, or adopted suitable existing software, because of licence concerns. Of particular note is the development, after licence restrictions were imposed on IPFilter, of the pf packet filter, which first appeared[30] in OpenBSD 3.0 and is now available in DragonFly BSD, NetBSD and FreeBSD. OpenBSD developers have also replaced GPL licensed tools (such as diff, grep and pkg-config) with BSD licensed equivalents and founded new projects including the OpenBGPD routing daemon and OpenNTPD time service daemon.[31] Also developed from scratch was the globally used software package OpenSSH and OpenSSL.

Security and code auditing

Shortly after OpenBSD's creation, Theo de Raadt was contacted by a local security software company named Secure Networks, Inc. or SNI.[32][33] They were developing a "network security auditing tool" called Ballista (later renamed to Cybercop Scanner after SNI was purchased by Network Associates), which was intended to find and attempt to exploit possible software security flaws. This coincided well with de Raadt's own interest in security, so for a time the two cooperated, a relationship that was of particular use leading up to the release of OpenBSD 2.3[34] and helped to form security as the focal point of the project.[35]

Until June 2002, the OpenBSD website featured the slogan:

Five years without a remote hole in the default install!

In June 2002, Mark Dowd of Internet Security Systems disclosed a bug in the OpenSSH code implementing challenge-response authentication.[36] This vulnerability in the OpenBSD default installation allowed an attacker remote access to the root account, which was extremely serious not only to OpenBSD, but also to the large number of other operating systems that were using OpenSSH by that time.[37] This problem necessitated the adjustment of the slogan on the OpenBSD website to:

One remote hole in the default install, in nearly 6 years!

The quote remained unchanged as time passed, until on March 13, 2007 when Alfredo Ortega of Core Security Technologies[38] disclosed a network-related remote vulnerability.[39] The quote was subsequently altered to:

Only two remote holes in the default install, in a heck of a long time!

This statement has been criticized because the default install contains few running services, and most users will install additional software.[40] The project states that the default install is intentionally minimal to ensure novice users "do not need to become security experts overnight",[41] which fits with open-source and code auditing practices argued to be important elements of a security system.[42]

OpenBSD includes features designed to improve security. These include API additions, such as the strlcat and strlcpy[43] functions; toolchain alterations, including a static bounds checker; memory protection techniques to guard against invalid accesses, such as ProPolice[44] and the W^X (W xor X) page protection feature; and cryptography and randomization features.[45]

To reduce the risk of a vulnerability or misconfiguration allowing privilege escalation, some programs have been written or adapted to make use of privilege separation, privilege revocation and chrooting. Privilege separation is a technique, pioneered on OpenBSD and inspired by the principle of least privilege, where a program is split into two or more parts, one of which performs privileged operations and the other—almost always the bulk of the code—runs without privilege.[46] Privilege revocation is similar and involves a program performing any necessary operations with the privileges it starts with then dropping them. Chrooting involves restricting an application to one section of the file system, prohibiting it from accessing areas that contain private or system files. Developers have applied these features to OpenBSD versions of common applications, including tcpdump and the Apache web server.[47]

OpenBSD developers were instrumental in the birth of—and the project continues to develop—OpenSSH, a secure replacement for Telnet. OpenSSH is based on the original SSH suite and developed further by the OpenBSD team.[48] It first appeared in OpenBSD 2.6 and is now the most popular SSH implementation, available on many operating systems.[49]

The project has a policy of continually auditing code for problems, work that developer Marc Espie has described as "never finished ... more a question of process than of a specific bug being hunted".[50] He went on to list several typical steps once a bug is found, including examining the entire source tree for the same and similar issues, "try[ing] to find out whether the documentation ought to be amended", and investigating whether "it's possible to augment the compiler to warn against this specific problem".

Linux kernel creator Linus Torvalds has expressed the view that development efforts should be focused on fixing general problems rather than targeting security issues, as non-security bugs are more numerous ("all the boring normal bugs are _way_ more important, just because there's a lot more of them"[51]). On July 15, 2008, he criticised the OpenBSD policy: "[T]hey make such a big deal about concentrating on security that they pretty much admit that nothing else matters to them".[52] OpenBSD developer Marc Espie replied to Torvalds' statement: "It's a totally misinformed opinion ... [Fixing normal bugs] is exactly what people in the OpenBSD project do, all the time".[53] Developer Artur Grabowski also expressed surprise: "That's the funniest part about this ... [Torvalds] was saying the same things we say".[54]

On 11 December 2010, Gregory Perry sent an email to Theo de Raadt alleging that the FBI had paid some OpenBSD ex-developers 10 years previously to insert backdoors into the OpenBSD Cryptographic Framework. Theo de Raadt made the email public on 14 December by forwarding it to the openbsd-tech mailing list and suggested an audit of the IPsec codebase.[55][56] De Raadt's response was skeptical of the report and he invited all developers to independently review the relevant code. In the weeks that followed, bugs were fixed but no evidence of backdoors were found.[57]

Uses

OpenBSD's security enhancements, built-in cryptography and the pf packet filter suit it for use in the security industry, for example on firewalls,[58] intrusion-detection systems and VPN gateways.

Proprietary systems from several manufacturers are based on OpenBSD, including devices from Armorlogic (Profense web application firewall),[59] Calyptix Security,[60] GeNUA mbH,[61] RTMX Inc,[62] and .vantronix GmbH.[63] Code from many of the OpenBSD system tools has been used in recent versions of Microsoft's Services for UNIX, an extension to the Windows operating system which provides some Unix-like functionality, originally based on 4.4BSD-Lite. Core Force, a security product for Windows, is based on OpenBSD's pf firewall.[64]

OpenBSD ships with the X window system[65] and is suitable for use on the desktop.[66] Packages for popular desktop tools are available, including desktop environments GNOME, KDE, and Xfce; web browsers Konqueror, Mozilla Firefox and Chromium; and multimedia programs MPlayer, VLC media player and xine.[67]

OpenBSD's performance and usability is occasionally criticised. Felix von Leitner's performance and scalability tests[68] indicated that OpenBSD lagged behind other operating systems. In response, OpenBSD users and developers criticised von Leitner's objectivity and methodology, and asserted that although performance is given consideration, security and correct design are prioritised, with project member Nick Holland commenting: "It all boils down to what you consider important."[69] OpenBSD is also a relatively small project, particularly when compared with FreeBSD and Linux, and developer time is sometimes seen as better spent on security enhancements than performance optimization. Critics of usability say that OpenBSD has a lack of user-friendly configuration tools, a bare default installation,[70] and a "spartan" and "intimidating" installer.[71] These see much the same rebuttals as performance: a preference for simplicity, reliability and security. As one reviewer puts it, "running an ultra-secure operating system can be a bit of work."[72]

Distribution and marketing

OpenBSD is available freely in various ways: the source can be retrieved by anonymous CVS or CVSup,[73] and binary releases and development snapshots can be downloaded either by FTP or HTTP.[74] Prepackaged CD-ROM sets can be ordered online for a small fee, complete with an assortment of stickers and a copy of the release's theme song. These, with its artwork and other bonuses, are one of the project's few sources of income, funding hardware, bandwidth and other expenses.[75]

In common with other operating systems, OpenBSD provides a package management system for easy installation and management of programs which are not part of the base operating system.[76] Packages are binary files which are extracted, managed and removed using the package tools. On OpenBSD, the source of packages is the ports system, a collection of Makefiles and other infrastructure required to create packages. In OpenBSD, the ports and base operating system are developed and released together for each version: this means that the ports or packages released with, for example, 4.6 are not suitable for use with 4.5 and vice versa.[77]

OpenBSD at first used the BSD daemon mascot created by Marshall Kirk McKusick.[78] Subsequent releases saw variations, eventually settling on Puffy,[79] described as a pufferfish.[80] Since then Puffy has appeared on OpenBSD promotional material and featured in release songs and artwork. The promotional material of early OpenBSD releases did not have a cohesive theme or design but later the CD-ROMs, release songs, posters and tee-shirts for each release have been produced with a single style and theme, sometimes contributed to by Ty Semaka of the Plaid Tongued Devils.[81] These have become a part of OpenBSD advocacy, with each release expanding a moral or political point important to the project, often through parody.[82] Past themes have included: in OpenBSD 3.8, the Hackers of the Lost RAID, a parody of Indiana Jones linked to the new RAID tools featured as part of the release; The Wizard of OS, making its debut in OpenBSD 3.7, based on the work of Pink Floyd and a parody of The Wizard of Oz related to the project's recent wireless work; and OpenBSD 3.3's Puff the Barbarian, including an 80s rock-style song and parody of Conan the Barbarian, alluding to open documentation.[83]

Bibliography

- The OpenBSD Command-Line Companion, 1st ed. by Jacek Artymiak. ISBN 83-916651-8-6.

- Building Firewalls with OpenBSD and PF: Second Edition by Jacek Artymiak. ISBN 83-916651-1-9.

- Mastering FreeBSD and OpenBSD Security by Yanek Korff, Paco Hope and Bruce Potter. ISBN 0-596-00626-8.

- Absolute OpenBSD, Unix for the Practical Paranoid by Michael W. Lucas. ISBN 1-886411-99-9.

- Secure Architectures with OpenBSD by Brandon Palmer and Jose Nazario. ISBN 0-321-19366-0.

- The OpenBSD PF Packet Filter Book: PF for NetBSD, FreeBSD, DragonFly and OpenBSD published by Reed Media Services. ISBN 0-9790342-0-5.

- Building Linux and OpenBSD Firewalls by Wes Sonnenreich and Tom Yates. ISBN 0-471-35366-3.

- The OpenBSD 4.0 Crash Course by Jem Matzan. ISBN 0-596-51015-2.

- The Book of PF A No-Nonsense Guide to the OpenBSD Firewall, 2nd edition by Peter N.M. Hansteen ISBN 978-1-59327-274-6 .

See also

- BSD Authentication

- BSD and GPL licensing

- Comparison of BSD operating systems

- Comparison of operating systems

- Comparison of operating system kernels

- Comparison of open source operating systems

- Hackathon

- KAME project

- pfSense

- POSSE project

- Security-focused operating system

References

- ^ a b "List of supported platforms on the OpenBSD website". Openbsd.org. 2010-11-22. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ^ a b The BSD Certification Group.; PDF of usage survey results.

- ^ a b Glass, Adam. Message to netbsd-users: Theo De Raadt(sic), December 23, 1994. Visited January 8, 2006.

- ^ Wayner, Peter. Free For All: How Linux and the Free Software Movement Undercut the High Tech Titans, 18.3 Flames, Fights, and the Birth of OpenBSD, 2000. Visited January 6, 2006.

- ^ Forbes. Is Linux For Losers? June 16, 2005. Visited January 8, 2006.

- ^ Linux.com. Theo de Raadt gives it all to OpenBSD, January 30, 2001. Visited March 3, 2010.

- ^ In this message the NetBSD core team acknowledge de Raadt's "positive contributions" to the project despite its problems with him.

- ^ Darknet. Intel Core 2 Duo Vulnerabilities Serious say Theo de Raadt, July 18, 2007. Visited May 8, 2011.

- ^ de Raadt, Theo. Mail to openbsd-announce: The OpenBSD 2.0 release, October 18, 1996. Visited December 10, 2005.

- ^ "Official OpenBSD Foundation site". Openbsdfoundation.org. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ^ Beck, Bob. Mail to openbsd-misc: Announcing: The OpenBSD Foundation, July 25, 2007. Visited July 26, 2007.

- ^ Multiple selections were permitted as a user may use multiple BSD variants side by side.

- ^ "DistroWatch.com". DistroWatch.com. 2001–2011. Retrieved 2011-06-12.

- ^ Chuck Cranor's site.

- ^ a b Cranor, Chuck D, de Raadt, Theo. Opening The Source Repository With Anonymous CVS, USENIX June 6–11, 1999. Visited April 07, 2010.

- ^ de Raadt, Theo. Mail to openbsd-misc: Adaptec AAC raid support, March 18, 2005. Visited December 9, 2005.

- ^ Scott Long's site.

- ^ Long, Scott. Post to OSNews: From a BSD and former Adaptec person..., March 19, 2005. Visited December 9, 2005.

- ^ de Raadt, Theo. Mail to freebsd-questions: aac support, March 19, 2005. Visited December 9, 2005.

- ^ de Raadt, Theo. Mail to freebsd-questions: aac support, March 19, 2005. Visited December 9, 2005.

- ^ OpenBSD CVS repository, commit by Theo de Raadt. Visited April 7, 2010.

- ^ a b de Raadt, Theo. Presentation at OpenCON, December 2006. Visited December 7, 2006.

- ^ OpenBSD.org. Copyright Policy. Visited January 7, 2006.

- ^ NewsForge. BSD cognoscenti on Linux, June 15, 2005. Visited January 7, 2006.

- ^ Linux.com. OpenBSD and ipfilter still fighting over license disagreement, June 06, 2001. Visited May 4, 2009.

- ^ Man pages: mrinfo and map-mbone.

- ^ de Raadt, Theo. Mail to openbsd-misc: Re: Why were all DJB's ports removed? No more qmail?, August 24, 2001. Visited December 9, 2005.

- ^ Bernstein, DJ. Mail to openbsd-misc: Re: Why were all DJB's ports removed? No more qmail?, August 27, 2001. Visited December 9, 2005.

- ^ a b Espie, Marc. Mail to openbsd-misc: Re: Why were all DJB's ports removed? No more qmail?, August 28, 2001. Visited December 9, 2005.

- ^ Hartmeier, Daniel. Design and Performance of the OpenBSD Stateful Packet Filter (pf). Visited December 9, 2005.

- ^ OpenBSD CVS logs showing import of diff, grep and pkg-config. OpenBGPD and OpenNTPD man pages from OpenBSD. Visited May 12, 2010.

- ^ The Age. Staying on the cutting edge, October 8, 2004. Visited January 8, 2006.

- ^ ONLamp.com. Interview with OpenBSD developers: The Essence of OpenBSD, July 17, 2003. Visited December 18, 2005.

- ^ Theo de Raadt on SNI: "Without their support at the right time, this release probably would not have happened." From the 2.3 release announcement. Visited December 19, 2005.

- ^ Wayner, Peter. Free For All: How Linux and the Free Software Movement Undercut the High Tech Titans, 18.3 Flames, Fights, and the Birth of OpenBSD, 2000. Visited April 7, 2010.

- ^ Internet Security Systems. OpenSSH Remote Challenge Vulnerability, June 26, 2002. Visited December 17, 2005.

- ^ A partial list of affected operating systems.

- ^ Core Security Technologies' homepage.

- ^ Core Security Technologies. OpenBSD's IPv6 mbufs remote kernel buffer overflow. March 13, 2007. Visited March 13, 2007.

- ^ Brindle, Joshua. Secure doesn't mean anything, March 30, 2008. Visited April 7, 2010

- ^ OpenBSD security page: "Secure by Default". Visited April 7, 2010.

- ^ Wheeler, David A. Secure Programming for Linux and Unix HOWTO, 2.4. Is Open Source Good for Security?, March 3, 2003. Visited December 10, 2005.

- ^ Miller, Todd C. and Theo de Raadt. strlcpy and strlcat – consistent, safe, string copy and concatenation. Proceedings of the 1999 USENIX Annual Technical Conference, June 6–11, 1999, pp. 175–178.

- ^ ProPolice site: here [1].

- ^ de Raadt, Theo, Niklas Hallqvist, Artur Grabowski, Angelos D. Keromytis, Niels Provos. Cryptography in OpenBSD: An overview (PDF), June 1999. Visited January 30, 2005.

- ^ Niels Provos. Privilege Separated OpenSSH. Visited January 30, 2006.

- ^ OpenBSD CVS logs showing addition of privilege separation to tcpdump and httpd man page describing the chroot mechanism. Visited May 12, 2010.

- ^ OpenSSH Project History and Credits. Accessed April 07, 2010.

- ^ SSH usage profiling. Accessed April 07, 2010.

- ^ O'Reilly Network. An Interview with OpenBSD's Marc Espie, March 18, 2004. Visited January 24, 2006.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus. Mail to linux-kernel: Re: [stable] Linux 2.6.25.10, July 15, 2008. Visited July 20, 2008.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus. Mail to linux-kernel: Re: [stable] Linux 2.6.25.10, July 15, 2008. Visited July 20, 2008.

- ^ Espie, Marc. Mail to openbsd-misc: Re: This is what Linus Torvalds calls openBSD crowd, July 16, 2008. Visited July 20, 2008.

- ^ Grabowski, Artur. Mail to openbsd-misc: Re: This is what Linus Torvalds calls openBSD crowd, July 16, 2008. Visited July 20, 2008.

- ^ "Allegations regarding OpenBSD IPSEC". Marc.info. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ^ ""FBI Added Secret Backdoors to OpenBSD IPSEC"". Osnews.com. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ^ Ryan, Paul (23 December 2010). "OpenBSD code audit uncovers bugs, but no evidence of backdoor". Ars Technica. Condé Nast Digital. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ McIntire, Tim. Take a closer look at OpenBSD, August 8, 2006—"Because OpenBSD is both thin and secure, one of the most common OpenBSD implementation purposes is as a firewall." Visited April 7, 2010.

- ^ Profense web application firewall.

- ^ Calyptix Security's website.

- ^ GeNUA mbH's homepage.

- ^ RTMX Inc homepage.

- ^ .vantronix GmbH's homepage.

- ^ http://corelabs.coresecurity.com/index.php?module=Wiki&action=view&type=project&name=Core_Force

- ^ "About Xenocara". Xenocara.org. 2006-07-10. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ^ Tzanidakis, Manolis. Using OpenBSD on the desktop, Linux.com, April 21, 2006. Visited April 07, 2010.

- ^ OpenBSD 4.9—"Over 6,800 ports...Gnome 2.32.1, KDE 3.5.10." Visited May 26, 2011.

- ^ Scalability test results and conclusions.

- ^ Holland, Nick. Mail to openbsd-misc: Re: OpenBSD Benchmarked... results: poor!, October 19, 2003. Visited January 8, 2006.

- ^ NewsForge. Trying out the new OpenBSD 3.8, November 2, 2005. Visited January 8, 2006.

- ^ NewsForge. Review: OpenBSD 3.5, July 22, 2004. Visited January 8, 2006.

- ^ DistroWatch. OpenBSD – For Your Eyes Only, 2004. Visited January 8, 2006.

- ^ OpenBSD anonymous CVS page. Visited April 7, 2010.

- ^ OpenBSD FTP page. Visited April 7, 2010.

- ^ OpenBSD orders page—"The proceeds from sale of these products is the primary funding of the OpenBSD project." Visited April 7, 2010.

- ^ OpenBSD FAQ 15 – The OpenBSD packages and ports system. Visited April 7, 2010.

- ^ OpenBSD FAQ 15.4.1 – I'm getting all kinds of crazy errors. I just can't seem to get this ports stuff working at all—"Do NOT check out a -current ports tree and expect it to work on a -release or -stable system." Visited April 7, 2010.

- ^ OpenBSD 2.4 CD cover showing the BSD daemon. Visited May 3, 2010.

- ^ OpenBSD 2.7 page with "spacefish" image. Visited May 3, 2010.

- ^ Although in fact pufferfish do not possess spikes and images of Puffy are closer to a similar species, the porcupinefish.

- ^ OpenBSD Release Songs. Visited April 7, 2010.

- ^ Matzan, Jem, OpenBSD 4.0 review, Software In Review, November 1, 2006. "Each OpenBSD release has a graphical theme and a song that goes with it. The theme reflects a major concern that the OpenBSD programmers are addressing or bringing to light." Visited April 7, 2010.

- ^ OpenBSD lyrics page Visited March 28, 2010.