Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath (formerly The Most Honourable Military Order of the Bath)[1] is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on May 18, 1725.[2] The name derives from the medieval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing (as a symbol of purification) as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath.[3] George I "erected the Knights of the Bath into a regular Military Order".[4] He did not (as is often stated) revive the Order of the Bath, since it had never previously existed as an Order, in the sense of a body of knights who were governed by a set of statutes and whose numbers were replenished when vacancies occurred.[5][6]

The Order consists of the Sovereign (currently HM Queen Elizabeth II), the Great Master (currently HRH The Prince of Wales),[7] and three Classes of members:[8]

- Knight Grand Cross (GCB) or Dame Grand Cross (GCB)

- Knight Commander (KCB) or Dame Commander (DCB)

- Companion (CB)

Members belong to either the Civil or the Military Division.[9] Prior to 1815 the order had only a single class, Knights Companion (KB), which no longer exists.[10] Recipients of the Order are now usually senior military officers or senior civil servants.[11][12]

The Order of the Bath is the fourth-most senior of the British Orders of Chivalry, after The Most Noble Order of the Garter, The Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle, and The Most Illustrious Order of St Patrick.[13] The last of the aforementioned Orders, which relates to Ireland, still exists but has been in disuse since the formation of the Irish Free State.[14]

History

Knights of the Bath

In the Middle Ages knighthood was often conferred with elaborate ceremonies. These usually involved the knight-to-be taking a bath (possibly symbolic of spiritual purification)[15] during which he was instructed in the duties of knighthood by more senior knights. He was then put to bed in order to dry. Clothed in a special robe, he was led with music to the chapel where he spent the night in a vigil. At dawn he made confession and attended Mass, then retired to his bed to sleep until it was fully daylight. He was then brought before the King, who after instructing two senior knights to buckle the spurs to the knight-elect's heels, fastened a belt around his waist, then struck him on the neck (with either a hand or a sword), thus making him a knight.[16] It was this "accolade" which was the essential act in creating a knight, and a simpler ceremony developed, conferring knighthood merely by striking or touching the knight-to-be on the shoulder with a sword,[17] or "dubbing" him, as is still done today. In the early medieval period the difference seems to have been that the full ceremonies were used for men from more prominent families.[15]

From the coronation of Henry IV in 1399 the full ceremonies were restricted to major royal occasions such as coronations, investitures of the Prince of Wales or royal Dukes, and royal weddings,[18] and the knights so created became known as Knights of the Bath.[15] Knights Bachelor continued to be created with the simpler form of ceremony. The last occasion on which Knights of the Bath were created was the coronation of Charles II in 1661.[19]

From at least 1625,[20] and possibly from the reign of James I, Knights of the Bath were using the motto Tria iuncta in uno (Latin for "Three joined in one"), and wearing as a badge three crowns within a plain gold oval.[21] These were both subsequently adopted by the Order of the Bath; a similar design of badge is still worn by members of the Civil Division. Their symbolism however is not entirely clear. The 'three joined in one' may be a reference to the kingdoms of England, Scotland and either France or Ireland, which were held (or claimed in the case of France) by British monarchs. This would correspond to the three crowns in the badge.[22] Another explanation of the motto is that it refers to the Holy Trinity.[11] Nicolas quotes a source (although he is skeptical of it) who claims that prior to James I the motto was Tria numina iuncta in uno, (three powers/gods joined in one), but from the reign of James I the word numina was dropped and the motto understood to mean Tria [regna] iuncta in uno (three kingdoms joined in one).[23]

Foundation of the Order

The prime mover in the establishment of the Order of the Bath was John Anstis, Garter King of Arms, England's highest heraldic officer. Sir Anthony Wagner, a recent holder of the office of Garter, wrote of Anstis's motivations:

It was Martin Leake's[24] opinion that the trouble and opposition Anstis met with in establishing himself as Garter so embittered him against the heralds that when at last in 1718 he succeeded, he made it his prime object to aggrandise himself and his office at their expense. It is clear at least that he set out to make himself indispensable to the Earl Marshal, which was not hard, their political principles being congruous and their friendship already established, but also to Sir Robert Walpole and the Whig ministry, which can by no means have been easy, considering his known attachment to the Pretender and the circumstances under which he came into office ... The main object of Anstis's next move, the revival or institution of the Order of the Bath was probably that which it in fact secured, of ingratiating him with the all-powerful Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole.[25]

The use of honours in the early 18th century differed considerably from the modern honours system in which hundreds, if not thousands, of people each year receive honours on the basis of deserving accomplishments. The only honours available at that time were hereditary (not life) peerages and baronetcies, knighthoods and the Order of the Garter (or the Order of the Thistle for Scots), none of which were awarded in large numbers (the Garter and the Thistle are limited to 24 and 16 living members respectively.) The political environment was also significantly different from today:

The Sovereign still exercised a power to be reckoned with in the eighteenth century. The Court remained the centre of the political world. The King was limited in that he had to choose Ministers who could command a majority in Parliament, but the choice remained his. The leader of an administration still had to command the King's personal confidence and approval. A strong following in Parliament depended on being able to supply places, pensions, and other marks of Royal favour to the government's supporters.[26]

The attraction of the new Order for Walpole was that it would provide a source of such favours to strengthen his political position.[27] George I having agreed to Walpole's proposal, Anstis was commissioned to draft statutes for the Order of the Bath. As noted above, he adopted the motto and badge used by the Knights of the Bath, as well as the colour of the riband and mantle, and the ceremony for creating a knight. The rest of the statutes were mostly based on those of the Order of the Garter, of which he was an officer (as Garter King of Arms).[28] The Order was founded by letters patent under the Great Seal dated 18 May 1725, and the statutes issued the following week.[29][30]

The Order initially consisted of the Sovereign, a Prince of the blood Royal as Principal Knight, a Great Master and thirty-five Knights Companion.[31] Seven officers (see below) were attached to the Order. These provided yet another opportunity for political patronage, as they were to be sinecures at the disposal of the Great Master, supported by fees from the knights. Despite the fact that the Bath was represented as a military Order, only a few military officers were among the initial appointments (see List of Knights Companion of the Order of the Bath). They may be broken down into categories as follows (note that some are classified in more than one category):[32]

- Members of the House of Commons: 14

- The Royal Household or sinecures: 11

- Diplomats: 4

- The Walpole family, including the Prime Minister: 3

- Naval and Army Officers: 3

- Irish Peers: 2

- Country gentlemen with Court Appointments: 2

The majority of the new Knights Companion were knighted by the King and invested with their ribands and badges on 27 May, 1725.[33] Although the statutes set out the full medieval ceremony which was to be used for creating knights, this was not performed, and indeed was possibly never intended to be, as the original statutes contained a provision[34] allowing the Great Master to dispense Knights Companion from these requirements. The original knights were dispensed from all the medieval ceremonies with the exception of the Installation, which was performed in the Order's Chapel, the Henry VII Chapel in Westminster Abbey, on June 17. This precedent was followed until 1812, after which the Installation was also dispensed with, until its revival in the twentieth century.[35] The ceremonies however remained part of the Statutes until 1847.[36]

Although the initial appointments to the Order were largely political, from the 1770s appointments to the Order were increasingly made for naval, military or diplomatic achievements. This is partly due to the conflicts Britain was engaged in over this period.[37][19] The Peninsular War resulted in so many deserving candidates for the Bath that a statute was issued allowing the appointment of Extra Knights in time of war, who were to be additional to the numerical limits imposed by the statutes, and whose number was not subject to any restrictions.[38] Another statute, this one issued some 80 years earlier, had also added a military note to the Order. Each knight was required, under certain circumstances, to supply and support four men-at-arms for a period not exceeding 42 days in any year, to serve in any part of Great Britain.[39] This company was to be captained by the Great Master, who had to supply four trumpeters, and was also to appoint eight officers for this body, however the statute was never invoked.[33]

Restructuring in 1815

In 1815, with the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the Prince Regent (later George IV) expanded the Order of the Bath

to the end that those Officers who have had the opportunities of signalising themselves by eminent services during the late war may share in the honours of the said Order, and that their names may be delivered down to remote posterity, accompanied by the marks of distinction which they have so nobly earned.[10]

The Order was now to consist of three classes: Knights Grand Cross, Knights Commander, and Companions. The existing Knights Companion (of which there were 60)[40] became Knight Grand Cross; this class was limited to 72 members, of which twelve could be appointed for civil or diplomatic services. The military members had to be of the rank of at least Major-General or Rear Admiral. The Knights Commander were limited to 180, exclusive of foreign nationals holding British commissions, up to ten of whom could be appointed as honorary Knights Commander. They had to be of the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel or Post-Captain. The number of Companions was not specified, but they had to have received a medal or been mentioned in despatches since the start of the war in 1803. A list of about 500 names was subsequently published.[41] Two further officers were appointed, an "Officer of arms attendant on the Knights Commander and Companions", and a "Secretary appertaining to the Knights Commanders and Companions"[10] The large increase in numbers caused some complaints that such an expansion would reduce the prestige of the Order.[11]

The Victorian era

In 1847 Queen Victoria issued new statutes eliminating all references to an exclusively military Order. As well as removing the word 'Military' from the full name of the Order, this opened up the grades of Knight Commander and Companion to civil appointments, and the Military and Civil Divisions of the Order were established. New numerical limits were imposed, and the opportunity also taken to regularise the 1815 expansion of the Order.[42][43] The 1847 statutes also abolished all the medieval ritual, however they did introduce a formal Investiture ceremony, conducted by the Sovereign wearing the Mantle and insignia of the Order, attended by the Officers and as many GCBs as possible, in their Mantles.[44]

In 1859 a further edition of the Statutes was issued; the changes related mainly to the costs associated with the Order. Prior to this date it had been the policy that the insignia (which were provided by the Crown) were to be returned on the death of the holder; the exception had been foreigners who had been awarded honorary membership. In addition foreigners had usually been provided with stars made of silver and diamonds, whereas ordinary members had only embroidered stars. The decision was made to award silver stars to all members, and only require the return of the Collar. The Crown had also been paying the fees due to the officers of the Order for members who had been appointed for the services in the recent war. The fees were abolished and replaced with a salary of approximately the same average value. The offices of Genealogist and Messenger were abolished, and those of Registrar and Secretary combined.[45]

The 20th century

In 1910 after his accession to the throne George V ordered the revival of the Installation ceremony,[19] perhaps prompted by the first Installation ceremony of the more junior Order of St Michael and St George, held a few years earlier,[46] and the building of a new chapel for the Order of the Thistle in 1911.[47] The Installation ceremony took place on July 22, 1913 in the Henry VII Chapel,[48][49] and Installations have been held at regular intervals since. Prior to the 1913 Installation it was necessary to adapt the chapel to accommodate the larger number of members. An appeal was made to the members of the Order, and following the Installation a surplus remained. A Committee was formed from the Officers to administer the 'Bath Chapel Fund', and over time this committee has come to consider other matters than purely financial ones.[50]

Another revision of the statutes of the Order was undertaken in 1925, to consolidate the 41 additional statutes which had been issued since the 1859 revision.[51]

Women were admitted to the Order in 1971.[19] In 1975, Princess Alice, Duchess of Gloucester, an aunt of Elizabeth II, became the first to reach the highest rank, Dame Grand Cross.[19] Princess Alice (whose maiden name was Lady Alice Douglas-Montagu-Scott) was a direct descendant of the Order's first Great Master,[52] and her husband, who had died the previous year, had also held that office.

Senior civil servants, such as permanent secretaries, and senior members of the armed forces, such as generals, are often appointed to the order. Civil servants associated with the Foreign Office, including ambassadors, are usually appointed to the Order of St Michael and St George.

Composition

Sovereign

The British Sovereign is the Sovereign of the Order of the Bath. As with all honours except those in the Sovereign's personal gift,[53] the Sovereign makes all appointments to the Order on the advice of the Government.

Great Master

The next-most senior member of the Order is the Great Master, of which there have been nine:

- 1725 – 1749: John Montagu, 2nd Duke of Montagu[54][55]

- 1749 – 1767: (vacant)

- 1767 – 1827: Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany

- 1827 – 1830: William, Duke of Clarence and St. Andrews (later King William IV)

- 1830 – 1837: (vacant)

- 1837 – 1843: Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex[56][57]

- 1843 – 1861: Prince Albert, the Prince Consort[58][59]

- 1861 – 1897: (vacant)

- 1897 – 1901: Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII)[60]

- 1901 – 1942: Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn[61]

- 1942 – 1974: Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester[62]

- 1974 – present: Charles, Prince of Wales.[7]

Originally a Prince of the Blood Royal, as the Principal Knight Companion, ranked next after the sovereign.[63] This position was joined to that of the Great Master in the statutes of 1847.[64] The Great Master and Principal Knight is now either a descendant of George I or "some other exalted personage"; the holder of the office has custody of the seal of the order and is responsible for enforcing the statutes.[65]

Members

The statutes also provide for the following:[19]

- 120 Knights or Dames Grand Cross (GCB) (of whom the Great Master is the First and Principal)

- 355 Knights Commander (KCB) or Dames Commander (DCB)

- 1,925 Companions (CB)

Regular membership is limited to citizens of the United Kingdom and of Commonwealth countries. Members appointed to the Civil Division must "by their personal services to [the] crown or by the performance of public duties have merited ... royal favour."[66] Appointments to the Military Division are restricted by the rank of the individual. GCBs must hold the rank of Rear Admiral, Major General or Air Vice Marshal.[67] KCBs must hold the rank of Captain in the Navy, Colonel in the Army or Marines, or Group Captain in the Air Force.[68] CBs must be of the rank of Lieutenant Commander, Major or Squadron Leader, and in addition must have been mentioned in despatches for distinction in a command position in a combat situation. Non-line officers (e.g. engineers, medics) may be appointed only for meritorious service in war time.[69]

Non-Commonwealth foreigners may be made Honorary Members.[70] Queen Elizabeth II has established the custom of awarding an honorary GCB to visiting heads of state, for example Gustav Heinemann (in 1972),[71] Ronald Reagan (in 1989), Lech Wałęsa (in 1991)[19], Fernando Henrique Cardoso, George H. W. Bush (in 1993)[72], Nicolas Sarkozy in March 2008,[73] and most recently, Turkish President Abdullah Gül.[74] Foreign generals are also often given honorary appointments to the Order, for example Georgy Zhukov,[75] Dwight D. Eisenhower and Douglas MacArthur during World War II,[76] and Norman Schwarzkopf[77] and Colin Powell[78] after the Gulf War. A more controversial member of the Order was Robert Mugabe, whose honour was stripped by the Queen, on the advice of Foreign Secretary, David Miliband, on June 25, 2008 as "as a mark of revulsion at the abuse of human rights and abject disregard for the democratic process in Zimbabwe over which President Mugabe has presided." [79]

Honorary members do not count towards the numerical limits in each class.[80] In addition the statutes allow the Sovereign to exceed the limits in time of war or other exceptional circumstances.[81]

Officers

The Order of the Bath now has six officers:

- the Dean

- the King of Arms

- the Registrar and Secretary

- the Deputy Secretary

- the Genealogist

- the Gentleman Usher of the Scarlet Rod

The office of Dean is held by the Dean of Westminster. The King of Arms, responsible for heraldry, is known as the Bath King of Arms; he is not, however, a member of the College of Arms, like many heralds. The Order's Usher is known as the Gentleman Usher of the Scarlet Rod; he does not, unlike his Order of the Garter equivalent (the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod) perform any duties in the House of Lords.

There were originally seven officers, each of whom was to receive fees from the Knights Companion both on appointment and annually thereafter. The office of Messenger was abolished in 1859.[82] The office of Genealogist was abolished at the same time, but revived in 1913.[83] The offices of Registrar and Secretary were formally merged in 1859, although the two positions had been held concurrently for the previous century.[84] An Officer of Arms and a Secretary for the Knights Commander and Companions were established in 1815,[10] but abolished in 1847.[85] The office of Deputy Secretary was created in 1925.

Under the Hanoverian kings certain of the officers also held heraldic office. The office of Blanc Coursier Herald of Arms was attached to that of the Genealogist, Brunswick Herald of Arms to the Gentleman Usher, and Bath King of Arms was also made Gloucester King of Arms with heraldic jurisdiction over Wales.[86] This was the result of a move by Anstis to give the holders of these sinecures greater security; the offices of the Order of the Bath were held at the pleasure of the Great Master, while appointments to the heraldic offices were made by the King under the Great Seal and were for life.[87]

Vestments and accoutrements

Members of the Order wear elaborate costumes on important occasions (such as its quadrennial installation ceremonies and coronations), which vary by rank:

- The mantle, worn only by Knights and Dames Grand Cross, is made of crimson satin lined with white taffeta. On the left side is a representation of the star (see below). The mantle is bound with two large tassels.[88]

- The hat, worn only by Knights and Dames Grand Cross and Knights and Dames Commanders, is made of black velvet; it includes an upright plume of feathers.[89]

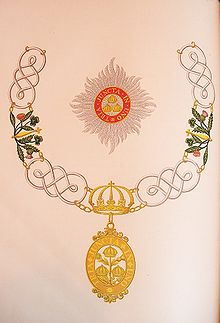

- The collar, worn only by Knights and Dames Grand Cross, is made of gold and weighs 30 troy ounces (933 g). It consists of depictions of nine imperial crowns and eight sets of flowers (roses for England, thistles for Scotland and shamrocks for Ireland), connected by seventeen silver knots.[88]

On lesser occasions, simpler insignia are used:

- The star is used only by Knights and Dames Grand Cross and Knights and Dames Commanders. Its style varies by rank and division; it is worn pinned to the left breast:

- The star for military Knights and Dames Grand Cross consists of a Maltese Cross on top of an eight-pointed silver star; the star for military Knights and Dames Commander is an eight-pointed silver cross pattée. Each bears in the centre three crowns surrounded by a red ring bearing the motto of the Order in gold letters. The circle is flanked by two laurel branches and is above a scroll bearing the words Ich dien (older German for "I serve") in gold letters.[88]

- The star for civil Knights and Dames Grand Cross consists of an eight-pointed silver star, without the Maltese cross; the star for civil Knights and Dames Commanders is an eight-pointed silver cross pattée. The design of each is the same as the design of the military stars, except that the laurel branches and the words Ich dien are excluded.[88]

- The badge varies in design, size and manner of wearing by rank and division. The Knight and Dame Grand Cross' badge is larger than the Knight and Dame Commander's badge, which is in turn larger than the Companion's badge;[90] however, these are all suspended on a crimson ribbon. Knights and Dames Grand Cross wear the badge on a riband or sash, passing from the right shoulder to the left hip.[88] Knights Commanders and male Companions wear the badge from a ribbon worn around the neck. Dames Commanders and female Companions wear the badge from a bow on the left side:

- The military badge is a gold Maltese Cross of eight points, enamelled in white. Each point of the cross is decorated by a small gold ball; each angle has a small figure of a lion. The centre of the cross bears three crowns on the obverse side, and a rose, a thistle and a shamrock, emanating from a sceptre on the reverse side. Both emblems are surrounded by a red circular ring bearing the motto of the Order, which are in turn flanked by two laurel branches, above a scroll bearing the words Ich dien in gold letters.[88]

- The civil badge is a plain gold oval, bearing three crowns on the obverse side, and a rose, a thistle and a shamrock, emanating from a sceptre on the reverse side; both emblems are surrounded by a ring bearing the motto of the Order.[88]

On certain "collar days" designated by the Sovereign, members attending formal events may wear the Order's collar over their military uniform or eveningwear. When collars are worn (either on collar days or on formal occasions such as coronations), the badge is suspended from the collar.[88]

The collars and badges of Knights and Dames Grand Cross are returned to the Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood upon the decease of their owners. All other insignia may be retained by their owners.[88]

Chapel

The Chapel of the Order is Henry VII Lady Chapel in Westminster Abbey.[91] Every four years, an installation ceremony, presided over by the Great Master, and a religious service are held in the Chapel; the Sovereign attends every alternate ceremony. The last such service was in May 2006 and was attended by the Sovereign.[19] The Sovereign and each knight who has been installed is allotted a stall in the choir of the chapel. Since there are a limited number of stalls in the Chapel, only the most senior Knights and Dames Grand Cross are installed. A stall made vacant by the death of a military Knight Grand Cross is offered to the next most senior uninstalled military GCB, and similarly for vacancies among civil GCBs.[91] Waits between admission to the Order and installation may be very long; for instance, Marshal of the Air Force Lord Craig of Radley was created a Knight Grand Cross in 1984, but was not installed until 2006.[19]

Above each stall, the occupant's heraldic devices are displayed. Perched on the pinnacle of a knight's stall is his helm, decorated with a mantling and topped by his crest. Under English heraldic law, women other than monarchs do not bear helms or crests; instead, the coronet appropriate to the dame's rank (if she is a peer or member of the Royal family) is used.[91]

Above the crest or coronet, the knight's or dame's heraldic banner is hung, emblazoned with his or her coat of arms. At a considerably smaller scale, to the back of the stall is affixed a piece of brass (a "stall plate") displaying its occupant's name, arms and date of admission into the Order.

Upon the death of a Knight, the banner, helm, mantling and crest (or coronet or crown) are taken down. The stall plates, however, are not removed; rather, they remain permanently affixed somewhere about the stall, so that the stalls of the chapel are festooned with a colourful record of the Order's Knights (and now Dames) throughout history.

When the grade of Knight Commander was established in 1815 the regulations specified that they too should have a banner and stall plate affixed in the chapel.[10] This was never implemented (despite some of the KCBs paying the appropriate fees) primarily due to lack of space,[92] although the 1847 statutes allow all three classes to request the erection of a plate in the chapel bearing the member's name, date of nomination, and (for the two higher classes) optionally the coat of arms.[93]

Precedence and privileges

Members of the Order of the Bath are assigned positions in the order of precedence.[94] Wives of male members also feature on the order of precedence, as do sons, daughters and daughters-in-law of Knights Grand Cross and Knights Commanders; relatives of female members, however, are not assigned any special precedence. Generally, individuals can derive precedence from their fathers or husbands, but not from their mothers or wives. (See order of precedence in England and Wales for the exact positions.)

Knights Grand Cross and Knights Commanders prefix "Sir," and Dames Grand Cross and Dames Commanders prefix "Dame," to their forenames.[95] Wives of Knights may prefix "Lady" to their surnames, but no equivalent privilege exists for husbands of Dames. Such forms are not used by peers and princes, except when the names of the former are written out in their fullest forms. Furthermore, honorary members and clergymen do not receive the accolade of knighthood.

Knights and Dames Grand Cross use the post-nominal "GCB"; Knights Commanders use "KCB"; Dames Commanders use "DCB"; Companions use "CB".[96]

Knights and Dames Grand Cross are also entitled to receive heraldic supporters.[97] Furthermore, they may encircle their arms with a depiction of the circlet (a red circle bearing the motto) with the badge pendant thereto and the collar; the former is shown either outside or on top of the latter.

Knights and Dames Commanders and Companions may display the circlet, but not the collar, around their arms. The badge is depicted suspended from the collar or circlet. Members of the Military division may encompass the circlet with "two laurel branches issuant from an escrol azure inscribed Ich dien", as appears on the badge.

Revocation

It is possible for membership in the Order to be revoked. Under the 1725 statutes the grounds for this were heresy, high treason, or fleeing from battle out of cowardice. Knights Companion could in such cases be degraded at the next Chapter meeting. It was then the duty of the Gentleman Usher to "pluck down the escocheon [i.e. stallplate] of such knight and spurn it out of the chapel" with "all the usual marks of infamy".[98] Only two people were ever degraded — Lord Cochrane in 1813 and General Sir Eyre Coote in 1816, both for political reasons, rather than any of the grounds given in the statute. Lord Cochrane was subsequently reinstated, Coote had died a few years after his degradation.[99]

Under Queen Victoria's 1847 statutes a member "convicted of treason, cowardice, felony, or any infamous crime derogatory to his honour as a knight or gentleman, or accused and does not submit to trial in a reasonable time, shall be degraded from the Order by a special ordinance signed by the sovereign". The Sovereign was to be the sole judge, and also had the power to restore such members.[100]

The situation today is that membership may be cancelled or annulled, and the entry in the register erased, by an ordinance signed by the Sovereign and sealed with the seal of the Order, on the recommendation of the appropriate Minister. Such cancellations may be subsequently reversed.[101]

William Pottinger, a senior civil servant, lost both his Companionship of the Order of the Bath and CVO in 1975 when he was gaoled for corruptly receiving gifts from the architect John Poulson.[102]

Romanian president Nicolae Ceauşescu was stripped of his honorary GCB by Queen Elizabeth II on 24 December 1989.

Robert Mugabe, President of Zimbabwe, was stripped of his honorary GCB by the Queen, on the advice of Foreign Secretary, David Miliband, on June 25, 2008 as "as a mark of revulsion at the abuse of human rights and abject disregard for the democratic process in Zimbabwe over which President Mugabe has presided."

See also

For people who have been appointed to the Order of the Bath, see the following categories:

- Category:Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- Category:Dames Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- Category:Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath

- Category:Dames Commander of the Order of the Bath

- Category:Knights Companion of the Order of the Bath

- List of Knights Companion of the Order of the Bath

- Category:Knights of the Bath

- Category:Companions of the Order of the Bath

- List of people who have declined a British honour

- List of revocations of appointments to orders and awarded decorations and medals of the United Kingdom

Notes

- ^ The word 'Military' was removed from the name by Queen Victoria in 1847. Letters Patent dated April 14, 1847, quoted in Statutes 1847

- ^ Statutes 1725, although Risk says 11 May

- ^ Anstis, Observations, p4

- ^ Letters patent dated 18 May 1725, quoted in Statutes 1725

- ^ Wagner, Heralds of England, p 357, referring to John Anstis, who proposed the Order, says: "He had the happy inspiration of reviving this ancient name and chivalric associations, but attaching it, as it never had been before, to an Order or company of knights."

- ^ Perkins, The Most Honourable Order of the Bath, p1 "It can scarcely be claimed that a properly constituted Order existed at any time during the preceding centuries [prior to the reign of Charles II]"

- ^ a b "No. 46428". The London Gazette. 10 December 1974.

{{cite magazine}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Statutes 1925, article 2

- ^ Statutes 1925, article 5

- ^ a b c d e "No. 16972". The London Gazette. 4 January 1815.

{{cite magazine}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c "www.royal.gov.uk article on the Order of the Bath as part of the Honours System". Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ^ Statutes 1925, articles 8–12

- ^ See, for example, the order of wear for orders and decorations, the Royal Warrant defining precedence in Scotland ("No. 27774". The London Gazette. 14 March 1905.

{{cite magazine}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)) or the discussion of precedence at http://www.heraldica.org/topics/britain/order_precedence.htm - ^ "www.royal.gov.uk article on the Order of St Patrick". Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ^ a b c Risk, History of the Order of the Bath, p6

- ^ The Manner of making Knights after the custom of England in time of peace and at the Coronation, that is Knights of the Bath, quoted in Perkins, pp 5–14

- ^ According to Anstis (Observations, p73) such knights were sometimes known as Knights of the Sword or Knights of the Carpet

- ^ Anstis, p66

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "www.royal.gov.uk feature article on the Order of the Bath". Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ^ Risk, p114

- ^ Nicolas, History of the orders of knighthood of the British empire, p38–9

- ^ The later usage by the Order of the Bath does not make things any clearer. The presence of the rose, thistle and shamrock (symbols of England, Scotland and Ireland respectively) in the Collar supports the above claim. The shamrocks however were not added until the 19th century, probably as a result of a suggestion of Sir Joseph Banks, who in his proposal observed that the presence of the shamrock would "greatly augment the meaning of the motto" (Risk, p 115). A further explanation for the crowns is provided in the 1725 statutes of the Order. The coat of arms which was to appear on the Order's seal (Azure three imperial crowns Or, that is, three gold imperial crowns on a blue background) was described as being anciently attributed to King Arthur.

- ^ Nicolas, p 38, quoting Bishop Kennet Register and Chronicle Ecclesiastical and Civil from the Restoration of King Charles II faithfully taken from the manuscripts of the Lord Bishop of Peterborough, (1728) p410

- ^ Garter King of Arms from 1754 to 1773, and an officer of arms for some 25 years before that

- ^ Wagner, pp348, 357

- ^ Risk, p2

- ^ In the words of his son, Horace Walpole, "The Revival of the Order of the Bath was a measure of Sir Robert Walpole, and was an artful bank of favours in lieu of places. He meant to stave off the demand for Garters, and intended that the Red [i.e. the Order of the Bath] should be a step to the Blue [the Order of the Garter]; and accordingly took one of the former for himself." Horace Walpole, Reminiscences (1788)

- ^ Nicolas, p237–8, Footnote

- ^ Risk, p4

- ^ Statutes 1725

- ^ Statutes 1725, article 2

- ^ Risk, p15,16

- ^ a b Risk, p16

- ^ Statutes 1725, article 6, the same article which state "[the Great Master shall] take especial care that ... the antient Rituals belonging to this Knighthood be observed with the greatest Exactness"

- ^ No Installation had been held between 1812 and the coronation of George IV in 1821, by which time the number of knights exceeded the number of stalls in the chapel. In order to allow the knights to wear their collars at the coronation (which they could not do until installed) they were dispensed from the Installation, and this precedent was subsequently followed. (Risk, p43)

- ^ Risk, p10

- ^ Risk, p20

- ^ Statute dated 8 May 1812, quoted in Statutes 1847

- ^ Statute dated 20 April 1727, quoted in Statutes 1847

- ^ The Times, 10 January 1815, p3

- ^ "No. 17061". The London Gazette. 16 September 1815.

{{cite magazine}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Letters Patent dated 14 April 1847

- ^ The document by which the Prince Regent modified the structure of the Order in 1815 was a Warrant under the Royal sign-manual. This is of lesser authority than Letters Patent under the Great Seal, by which the Order and its Statutes were originally established. It had been questioned on a number of occasions whether the Statutes of the Order could be modified by anything less than such Letters Patent. The 1847 Letters Patent retroactively confirmed the validity of the 1815 document and the subsequent appointments to the Order

- ^ Risk, p61

- ^ Risk, p70

- ^ Risk, p89

- ^ Perkins, p122

- ^ Risk, p92

- ^ Perkins, p124–131

- ^ Risk, p95–6

- ^ 16 in Queen Victoria's reign, 6 in Edward VII's and 19 in George V's. (Risk, p97)

- ^ Risk, p102

- ^ The Order of the Garter, the Order of the Thistle, the Order of Merit and the Royal Victorian Order

- ^ "No. 6376". The London Gazette. 25 May 1725.

{{cite magazine}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Nicolas, Appendix p. lxx gives the first four Great Masters, although he considers the latter three to have only been acting Great Masters

- ^ "No. 19570". The London Gazette. 19 December 1837.

{{cite magazine}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "No. 19592". The London Gazette. 23 February 1838.

{{cite magazine}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Prince Albert was appointed acting Great Master sometime in 1843, and the appointment was made substantive by the 1847 Statutes, article 4. Risk says that he was appointed acting Great Master on March 31, 1843, however The Times, reporting the death of the Duke of Sussex (April 22 1843, pp4–5) says that the office of acting Great Master became vacant on his death. At any rate when the executors of the Duke of Sussex delivered his insignia together with the seal and statutes to the Queen on June 20 (The Times, 21 June 1843, p6) Prince Albert was then acting Great Master.

- ^ "No. 20737". The London Gazette. 25 May 1847.

{{cite magazine}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ The Times, 22 June 1897, p10

- ^ "No. 27289". The London Gazette. 26 February 1901.

{{cite magazine}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ The Times, 25 February 1942, p7

- ^ Statutes 1725, article 4

- ^ Letters Patent dated 14 April 1847, quoted in Statutes 1847

- ^ Statutes 1925, article 5

- ^ Statutes 1925, article 9

- ^ Statutes 1925, article 8

- ^ Statutes 1925, article 10

- ^ Statutes 1925, article 12

- ^ Statutes 1925, article 15

- ^ The Times, 25 October 1972, p21

- ^ The Times, 1 December 1993, p24

- ^ Nicolas Sarkozy awarded honorary title

- ^ "Queen cherishes UK-Turkey ties" (in Turkish). Turkish Daily News. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ The Times, Issue 50193; July 13, 1945; pg. 4; col A

- ^ The Times, May 27, 1943, p4

- ^ The Times, 21 May 1991

- ^ "Biography of Colin Powell". Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ^ Queen strips Robert Mugabe of knighthood in 'revulsion' at violence

- ^ Statutes 1925, article 18

- ^ "In the event of any future wars or of any action or services civil or military meriting peculiar honour and reward...to increase the numbers in any of the said classes and in any of the said divisions". Statutes 1925, article 17

- ^ Risk, p70

- ^ Risk, p93

- ^ Risk, pp13, 70

- ^ Statutes 1847, article 15

- ^ Statute dated 17 January 1726 (according to Risk, p14). Both the 1812 and 1847 editions of the Statutes give the date as 17 January 1725, but this is most probably a misprint since the Order was not founded until May 1725, and the additional statute also specified the office holders by name.

- ^ Risk, p14

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Statutes 1925, article 23

- ^ The hat was formerly of white satin (Statutes 1725, article 8), but was changed to black velvet at the command of George IV for his coronation (Nicolas, p198). The hat is not explicitly specified in the 1847 or 1925 statutes

- ^ Statutes 1925, articles 23,24,25

- ^ a b c Statutes 1925, article 21

- ^ Risk, p40

- ^ Statutes 1847, article 18

- ^ Statutes 1925, article 22

- ^ Statutes 1925, article 20

- ^ www.honours.gov.uk summary of the Orders of Chivalry. The postnominal letters are not mentioned in the Statutes of the Order

- ^ Statutes 1925, article 28

- ^ Statutes 1725 art 3

- ^ Risk, p30

- ^ Statutes 1847, article 26

- ^ Statutes 1925, article 30

- ^ "No. 46561". The London Gazette. 2 May 1975.

{{cite magazine}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

References

- Anstis, John (1752). Observations introductory to an historical essay, upon the Knighthood of the Bath. London: James Woodman.

- Galloway, Peter (2006). The Order of the Bath. Phillimore. ISBN 1-86077-399-0.

- Nicolas, Nicholas H. (1842). History of the orders of knighthood of the British empire, Vol iii. London.

- Perkins, Jocelyn (1920). The Most Honourable Order of the Bath : a descriptive and historical account (2nd edition ed.). London: Faith Press.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Risk, James C. (1972). The History of the Order of the Bath and its Insignia. London: Spink & Son.

- Statutes of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath. London. 1725.

- Statutes of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath. London. 1812.

- Statutes of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath. London. 1847.

- Statutes of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath. London. 1925.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Royal Insight > May 2006 > Focus: The Order of the Bath". Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- "Monarchy Today > Queen and Public > Honours: The Order of the Bath". Retrieved 2006-09-09.

External links

- Brennan, I. G. (2004). "The Most Honourable Order of the Bath."

- Cambridge University Heraldic and Genealogical Society. (2002). "The Most Honourable Order of the Bath."

- Velde, F. R. (2003). "Order of Precedence in England and Wales."